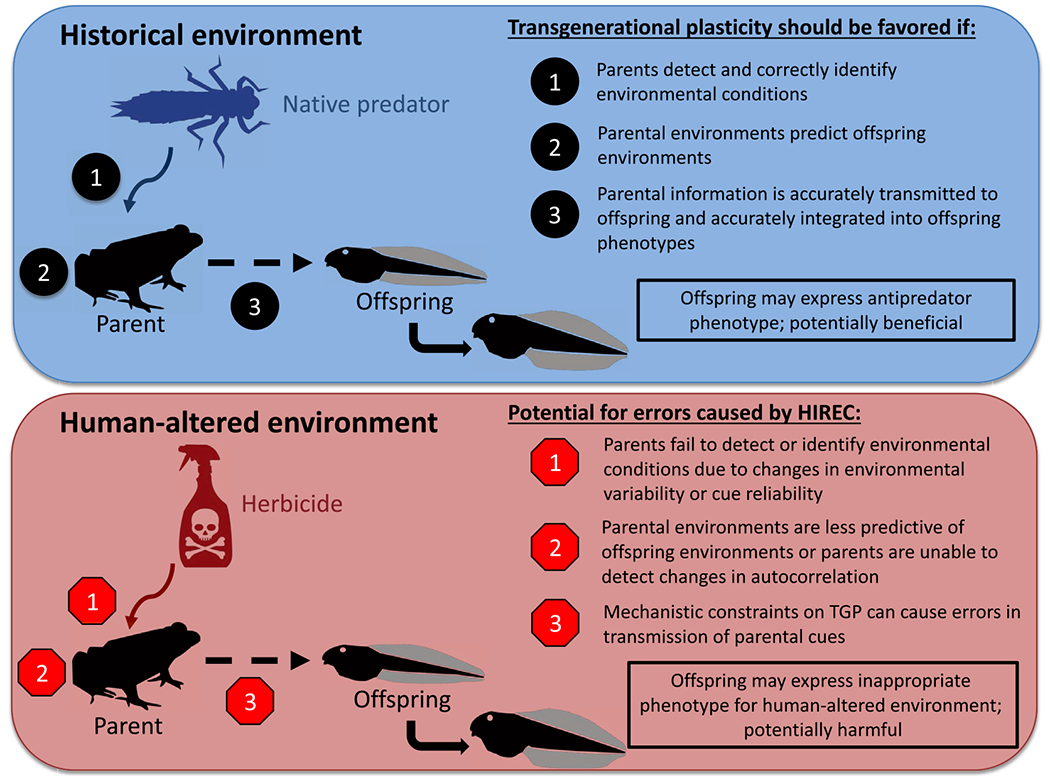

Figure 1. Overview of the Key Determinants of the Transgenerational Consequences of Human-Induced Rapid Environmental Change (HIREC) Using a Hypothetical Example.

Transgenerational plasticity (TGP) is a process by which offspring phenotypes are altered by environments experienced by previous generations (e.g., parents). Parental experiences can be conveyed to offspring through a variety of potential mechanisms, but TGP involves three general processes (top panel). In historical environments, TGP is more likely to be favored when these processes occur with minimal error. This is likely if: (i) parents possess the sensory/biochemical systems to accurately detect and identify environmental conditions and cue reliability is high, (ii) temporal/spatial environmental variability is low or similar to historic conditions and/or temporal/spatial autocorrelation is high, and (iii) parents can accurately transmit information about their environment to offspring and offspring can accurately integrate that information into their phenotype. Human-altered environments (bottom panel) increase the potential for errors in each of these processes. This may be due to the introduction of novel environmental conditions (which may reduce cue reliability), increases in environmental variability, or decreases in environmental autocorrelation relative to historic environments. HIREC may also increase the likelihood of mismatches between offspring phenotypes and human-altered environments and lead to detrimental effects of TGP. Visual example in both panels adapted from [66], who found that direct exposure to predator risk cues from dragonfly larvae cause tadpole prey to develop an antipredator phenotype (deeper tails) and that exposure to herbicides can elicit this same phenotypic response. We extend this WGP example to suggest possible errors in the process of TGP. Images by M. Bensky.