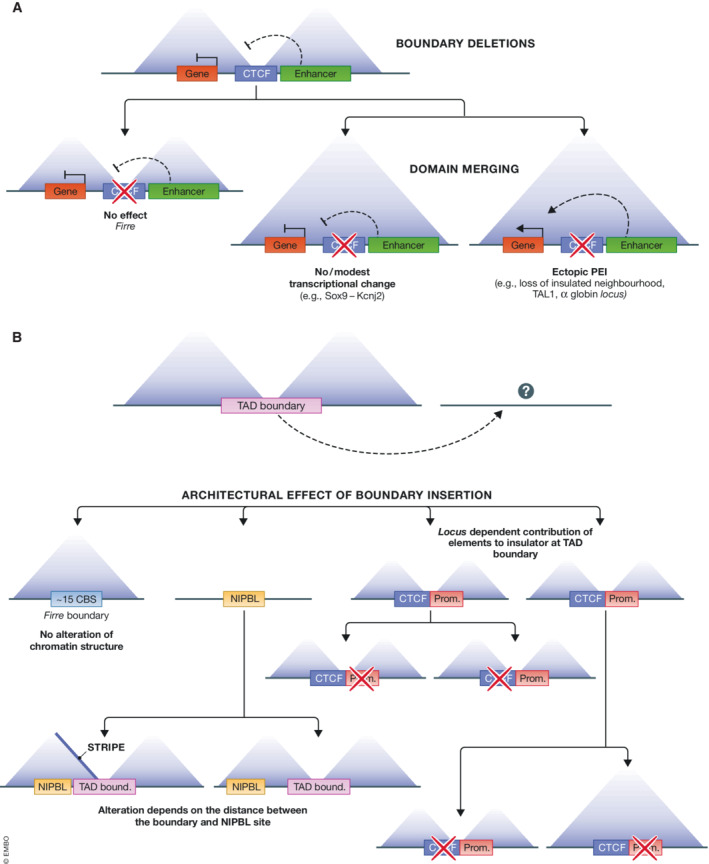

Figure 2. Genome engineering reveals locus‐specific transcriptional and architectural consequences of TAD boundary deletion and insertion.

(A) TAD or a sub‐TAD boundary deletion may lead to no overt alteration of chromatin architecture as seen at the Firre locus (Barutcu et al, 2018), or to TAD and subTAD merging accompanied by either modest (Sox9/Kcjn2; Despang et al, 2019) or considerable transcriptional changes (e.g., loss of insulated neighbourhoods and oncogene activation; Hnisz et al, 2016), or aberrant activation of genes as, for example in the vicinity of otherwise insulated globin genes (Hanssen et al, 2017). (B) Ectopic insertion of a boundary element may lead to no change in the architecture of the recipient locus (Barutcu et al, 2018). When considering other CBS, boundaries can still be formed despite the deletion of the CBS. Depending on whether the ectopic boundary is inserted far or close to a Nipbl cohesin loader binding site, the boundary may form stripes (Redolfi et al, 2019). The contribution of distinct elements making up the boundary depends on the intrinsic features of the target locus. At one location, a boundary composed of a CBS site and a housekeeping gene promoter depends on both elements, while at another location CTCF appears less crucial for boundary formation (Zhang et al, 2020).