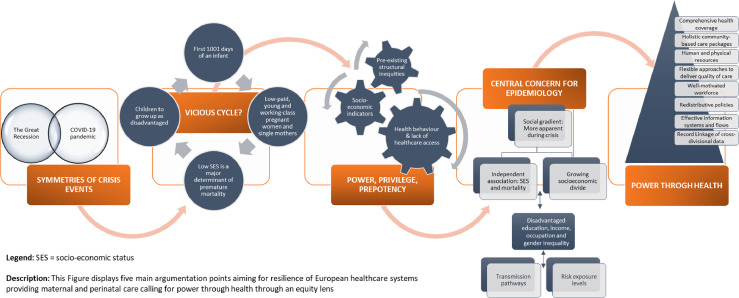

The Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic, two major crisis events with symmetries across Europe, had a multidimensional impact on access, quality, and outcomes of perinatal and maternal healthcare. It is time to look at what we can learn from these crisis events and to urgently focus on perinatal and maternal healthcare access and quality (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Power through Health.

The three-tiered reasons are simple: Firstly, crisis and their subsequent impact on perinatal and maternal healthcare may particularly impede a healthy start into life, especially when affecting the first 1001 days of an infant, a critical period to future health.1 Secondly, intensified economic impacts are felt especially by low-paid, young, and working-class pregnant women and single mothers who often hold insecure occupations and tend to live close to poverty; thus are one of the first to suffer from economic hardship, adverse health consequences, and health inequities.2 Thirdly, low socio-economic-status (SES) is a major determinant of premature mortality, and may condemn children to grow up as disadvantaged leading to a vicious circle of inequalities in mortality.3

Privilege, power, and prepotency are intertwined concepts with numerous pre-existing structural inequities that have predisposed how the Great Recession was experienced and the mode that COVID-19 was and is transmitted.4 Maintaining privileges during crisis events has been a tacit and dominant motivation for the majority of actions predominantly powered by the privileged or those in power and with high prepotency, who however often undergo a fundamentally unalike experience of the crisis from those who are unprivileged. Socio-economic indicators influence structural inequities, felt by women and children with less power, privilege, and prepotency, and with it the risk to suffer from the economic and financial consequences and furthermore intensify in contexts of fragility, conflict, and disasters where social cohesion is heretofore destabilized and institutional capacity and healthcare services are limited.4 Hence, their worse health outcomes is mainly explained by two mechanisms: health behaviour and lack of access to high quality healthcare.5,6

Thus, are we hypothecating the future of our society by overlooking the health, social, and economic impact of these critical crises in socioeconomically disadvantaged mothers and children?

Social inequalities should be a central concern of epidemiology.7 This concern gets even more apparent during crisis events. The independent association between SES and mortality is comparable in strength and consistency across countries to those for the 25×25 risk factors.8 The social gradient, “whereby people who are less advantaged in terms of SES have worse health (and shorter lives) than those who are more advantaged”, is especially apparent in events of crises by growing socioeconomic divide in economic distress5,6 reflecting a combination of disadvantaged education, income, and occupation, and through gender inequality.6

The outlook of a new financial crisis and of a revival of high long-term unemployment rates reinstates the risk for a new worsening. We call for “Power through Health”: involving with power imbalances through a public equity lens – to direct decision-making to circumvent assumptions based on biases and to disassemble barriers that prevent equal participation of individuals.

Recommendations

The WHO calls to strengthen resilience of healthcare systems as crisis management strategy.9 Focussing on healthcare access and quality for women and children to allow to “give every child the best start in life”,3 we call for:

-

1.

Comprehensive health coverage by decreasing or eliminating user charges to remove healthcare access barriers9;

-

2.

Holistic community-based care packages during maternity period addressing health inequities and decreasing perinatal mortality rates5,6;

-

3.

Appropriate level and sufficient distribution of human and physical resources allowing to increase capacity and provide the necessary flexibility9;

-

4.

Alternative and flexible approaches to deliver quality of care to initiate innovative programs (e.g., teleconsultations)9;

-

5.

Robust, flexible, and well-motivated workforce who are well-supported9;

-

6.

Redistributive policies pushing families with young children above poverty line (e.g., paid parental leave with paternal incentives, nurse monitoring in the first months of life, universal access to publicly funded high quality early childhood education programmes)1;

-

7.

Effective information systems and flows being at the core of the decision-making throughout any policy process as surveillance is particularly vital in the early stages of a crisis event9;

-

8.

Record Linkage of cross-divisional data, in line with WHO's call for Science, Solution, and Solidarity as three key aims to overcome COVID-19 asserting togetherness.10

Women and children with lower SES, who have been one of the most hit by the Great Recession and also during the COVID-19 pandemic, may be expected to remain particularly vulnerable in any future crisis event. The suggested policies should be considered investment priorities with particular added importance during all types of crises to promote better health across the social gradient and to overcome adverse perinatal outcomes.

Contributors

JND: conceptualisation, data curation, visualisation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing– review & editing; TL: writing– review & editing, supervision; TK: writing– review & editing, supervision; funding acquisition; HB: writing– review & editing; supervision; funding acquisition.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Funding

The study received funding by the Foundation for Science and Technology—FCT (Portuguese Ministry of Science, Technology and Higher Education), under the Unidade de Investigação em Epidemiologia—Instituto de Saúde Pública da Universidade do Porto (EPIUnit) and the Laboratório Associado (ITR) UIDB/04750/2020 and LA/P/0064/2020. This study was also funded by the external PhD programme of Maastricht University (UM), Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences (FHML), Care and Public Health Research Institute (CAPHRI), Maastricht, The Netherlands. The salary of JD was paid during the initial phase of the study by the RECAP preterm project which has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No 733280.

References

- 1.Hertzman C, Siddiqi A, Hertzman E, et al. Tackling inequality: get them while they're young. BMJ. 2010;340(7742):346. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chmielewska B, Barratt I, Townsend R, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Heal. 2021;9(6):e759–e772. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(21)00079-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot M, Bell R. Fair society, healthy lives (Full report) Public Health. 2012;126(Suppl 1):S4–S10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in us public health research: Concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18(16):341–378. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.JB Judis. Paul Krugman vs. Joseph Stiglitz How income inequality could be slowing our recovery from the Great Recession. 2013. Available from: https://newrepublic.com/article/112278/paul-krugman-vs-joseph-stiglitz-inequality-slowing-recovery

- 6.Ahmed F, Ahmed N, Pissarides C, Stiglitz J. Why inequality could spread COVID-19. Lancet Public Heal. 2020;5(5):e240. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30085-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marmot M, Bell R. Social inequalities in health: A proper concern of epidemiology. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26(4):238–240. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stringhini S, Carmeli C, Jokela M, et al. Socioeconomic status and the 25 × 25 risk factors as determinants of premature mortality: a multicohort study and meta-analysis of 1·7 million men and women. Lancet. 2017;389(10075):1229–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32380-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas S, Sagan A, Larkin J, Cylus J, Figueras J, Karanikolos M. European Observatory of Health Systems and Policies. WHO; 2020. Strengthening health systems resilience, key concepts and strategies; p. 33.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332441/Policy-brief-36-1997-8073-eng.pdf Available from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doetsch JN, Dias V, Indredavik MS, et al. Record linkage of population-based cohort data from minors with national register data: a scoping review and comparative legal analysis of four European countries. Open Res Eur. 2021;1:58. doi: 10.12688/openreseurope.13689.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]