Abstract

Organizations shifted employees to a work from home schedule as a protective health measure during the COVID-19 pandemic. This paper depicts the path through which the abrupt workplace disruptions can trigger employees’ perceptions of felt mistrust, intensify work to life conflict, and cause a psychological contract breach. In study 1, we conducted an experiment with 133 college students and found that switching to a work from home schedule with enhanced supervisor control increased the psychological contract breach through felt mistrust. In Study 2, we surveyed 239 adults who worked from home during the pandemic. Results underline the role of work to life conflict as a mediator through which disruptions and felt mistrust influenced the breach of psychological contract. Further, coping strategies were found to mitigate this detrimental effect. Overall, our findings suggest that sudden shifts in management practices can challenge workplace relationships during environmental shocks.

Keywords: Psychological contract breach, Work to life conflict, Felt mistrust, Coping, Disruption

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic led to widespread business disruptions in the United States. Many organizations were forced to temporarily close their offices and schedule their employees to work from home. Schools were also closed and working parents had the additional responsibility for the care and education of their children during hours they typically devoted to work. News about the spreading virus and subsequent fatalities from the disease lead to widespread stress. To reduce contagion, local governments also restricted their residents from participating in many traditional social and recreational activities. Deepening the employees’ anxiety, furloughs and layoffs increased and the unemployment rate skyrocketed (https://www.bls.gov). Surviving employees faced heavier workloads, while many struggled with mounting demands from home.

The business responses to the COVID-19 pandemic caused shock to the employees’ work arrangements, which led to great uncertainty in the employment relationship, shifted the boundaries between work and home, and disrupted the maintenance of the psychological contract. In this study, we investigate the impact of this shock on the breach of the employees’ psychological contracts. Our findings suggest that a psychological contract breach can be predicted by certain factors that are especially relevant in the context of this study, including workplace disruptions (Beal & Ghandour, 2011), felt trust (Robinson, 1996), and work to life conflict (Rosen, Chang, Johnson, & Levy, 2009). Specifically, we report that the shock event of moving to a work from home schedule set off a chain reaction that threatened employee perceptions of supervisor trust, which led to an increased perception of conflict between work and home, and thus promoted the recognition of a breach of psychological contract. Our findings, however, suggest that coping strategies tended to reduce the effect of work to life conflict on the perception of a psychological contract breach.

Although the advancement of technology enables a flexible work arrangement, organizations have previously been hesitant to let most employees work from home (Masuda, Holtschlag, & Nicklin, 2017). The hesitation reflected several concerns from management. These included a lack of social cues in communication and loss of real-time control of employee task-focused behaviors. During the pandemic, supervisors were obliged to manage their employees remotely, putting the work from home schedule to a long-term test. Our investigation of the dynamics of the psychological contract in these circumstances contributes to the literature in three aspects. First, we enrich the psychological contract literature by establishing the effect of workplace disruptions at home on felt mistrust, which eventually results in a psychological contract breach. Specifically, we found that work from home employees were sensitive to workplace disruptions and tended to perceive such disruptions as signs of supervisor mistrust. Although not all of the disruptions during the pandemic were caused by the employers, the impact of disruptions on feelings of supervisor mistrust was significant. We argue that the employers’ concerns about the work from home schedule may have prompted organizational practices that reduced employee feelings of support.

Second, we maintain that work to life conflict plays an active role in determining the perception of a psychological contract breach. Previous literature on psychological contracts primarily focuses on the workplace at the employers’ site and largely ignores the impact of affective events occurring at home. While a balance between work and life has long been desired by employees, the importance of work-life balance to the psychological contract has received limited attention. Our research fills this gap in the literature by highlighting the need for both employers and employees to recognize and manage the level of work to life conflict. As the work from home schedule gains popularity among organizations, the investigation on work to life conflict and its influence on the psychological contract is increasingly relevant.

Finally, we contribute to the literature on remote work by investigating work-related coping strategies. Given that a large-scale work from home schedule is relatively new to many organizations, investigations on coping strategies to manage disruptions related to the remote workplace is limited. For employees, these strategies aim at straightforward, task-specific communication with the supervisors, building a mutual understanding of the challenges for the remote workplace, and pushing back on unattainable expectations. Our study indicates that these strategies may alleviate the pressure of work to life conflict on the psychological contract.

In the following sections, we discuss the mediators and a moderator in the workplace disruption process and test the research model using two studies. Study 1 is an experimental study conducted with 133 undergraduate students. Study 2 is a field study which collected survey data from 239 employees who worked from home during the early months of the pandemic. The results of our data analysis are reported, followed by a discussion of contributions and implications.

2. Literature review and theory development

2.1. Psychological contract breach (PCB)

The psychological contract is defined as “individual beliefs, shaped by the organization, regarding terms of an exchange agreement between individuals and their organization” (Rousseau, 1995, p. 9). From the employee’s perspective, a psychological contract is an implicit understanding of the obligations the organization assumes to maintain the employment relationship. Compared to a written contract, the psychological contract is less formal. Whereas the written contract often defines the terms of a clear-cut exchange of resources between the employee and the organization, the psychological contract involves conditions that foster interdependence between the parties. As such, the psychological contract depicts the subtleties in the employment relationship.

A breach in the psychological contract is a disturbing emotional process which comes about when there is an unresolved disruption in the stable psychological contract between employer and employee (Rousseau, Hansen, & Tomprou, 2018). The literature provides ample evidence that a psychological contract breach (PCB) has an impact on affective, attitudinal, and behavioral employee outcomes (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019, Parzefall and Jacqueline, 2011). For example, research suggests that a PCB leads to negative job attitudes such as reduced job satisfaction, reduced organizational commitment, and increased turnover intention. A breach in the psychological contract was also found to jeopardize employee trust in the supervisor and organization, increase stress and emotional exhaustion, and contribute to daily emotional reactions. Further, a PCB leads to counter-productive behaviors such as impeded organizational citizenship behavior, suppressed job performance, absenteeism, and workplace deviance behavior (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019).

The antecedents of a PCB have also been studied, although to a lesser extent. One area of study is that of the context in which the psychological contract breach takes place. “Events external to the organization are essential influences on an individual’s judgment of breach” (Coyle-Shapiro et al., 2019, p. 152). During employment, if organizational promises are not delivered, the employee perceives a breach. A PCB does not necessarily result from a purposeful action on the part of the employer. There are times when extenuating circumstances preclude the fulfillment of the psychological contract (Morrison & Robinson, 1997). Nevertheless, even if the company’s failure to meet expected obligations is due to changes in the external environment, employees may still perceive a breach in the psychological contract. This paper examines this not-so-obvious effect and highlights the significance of environmental disruptions to the state and process of psychological contract.

2.2. Pandemic-induced workplace disruptions

The COVID-19 pandemic created a chain reaction that fundamentally altered employees’ day-to-day lives in terms of job duties, working conditions, and work schedules. Although the strength and type of disruptions vary by individual and position, disruptions none-the-less were widespread. Employees who shifted to a work from home schedule in the early months of the pandemic (March to August 2020) found that their job duties and related tasks were adjusted to accommodate a remote workplace. These changes included more time on the computer or telephone; less time working face-to-face with supervisors, co-workers, and customers; and more documentation of how or when work was performed. In addition, when employees were moved to a work from home schedule, working conditions were also impacted. Working conditions are often tied to a specific physical location and are also related to established relationships with co-workers and supervisors. Finally, not only did the location of the workplace switch to employees’ homes due to widespread lockdown policies, but the home-based workplace often came in conflict with employees’ responsibilities related to child, elder, and home care. These added responsibilities led to potential disruptions in the work schedule when family or home responsibilities demand attention during the usual workday.

According to affective events theory, disruptive events cause variation in individuals’ emotions and moods. The speed and magnitude of these disruptive events intensifies the impact of these changes on the emotions of the employees (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996). While relatively small negative events may prompt a primary appraisal, which results in the short-term effects of a negative mood, a series of affective events is likely to cause both primary and secondary appraisal that creates a longer term negative emotional experience (Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996).

It is worth noting that the COVID-19 pandemic, which caused the transition to a work from home schedule, served as an exogenous shock that set to irregulate the affective states of the employees. For the employees, stress and uncertainty from society, the organization, and the home rose abruptly, while coping resources were greatly limited due to restricted community and social support/activities (Lin, Shao, Li, Guo, & Zhan, 2021). Homelife became a battlefield of resource exploitation, as the pandemic attacked the interdependence of social entities in the modern world and exposed the vulnerability of this interdependence to an environmental crisis. This shock, as well as its aftershocks, brought chaos to the employees’ emotional experiences, as they tried to adapt to sudden changes of numerous work and life conditions under eruptive pressure. Given that a shock may result in both enhanced affective reactions as well as strong regulation efforts (Beal & Ghandour, 2011), the present paper seeks to observe the impact of these outcomes on the employees’ perceptions of a breach in their psychological contracts.

Morrison and Robinson (1997) suggest that a psychological contract breach begins with one of two circumstances: reneging or incongruence. Under the condition of reneging, the organization has either an inability or unwillingness to fulfill promises made to employees. This differs from incongruence, where the employer believes that promises have been fulfilled, yet the employee disagrees. The current study investigates the condition of reneging. Reilly, Brett, and Stroh (1993) argue that organizational turbulence, defined as “changes experienced by the organization that are nontrivial, rapid, and discontinuous”, impacts employee attitudes about their jobs and organizations (p. 167). Thus, organizational turbulence or organizational change, would meet the circumstance under which an organization might find it necessary to renege on promises made to employees. “The likelihood of reneging will increase as the rate of organizational turbulence increases” (Morrison & Robinson, 1997, p. 233). Employees expect that organizations will provide suitable working conditions (Guest, 1998), including workspaces and equipment to perform their jobs. Some organizations may be better prepared for the lockdown policies than others. For example, those organizations that had previously offered telecommuting options might have the experience about the equipment and support employees may need to work from home. Some of these organizations may have found it easier to maintain the psychological contract, as both the employers and the employees were familiar with the work from home concept. However, in the turbulence during the pandemic, the lockdown measure led to many changes that were out of the organizations’ control, so that even organizations with prior work from home experience may have found it difficult to maneuver. For example, neither the organization nor the employees would be ready to deal with the loss of childcare or for parents to provide schooling services at home, which forced many employees to change their way of working. Failure to address such unexpected conditions properly could cast doubt on the robustness of the psychological contract.

In a test of reneging as an antecedent to a PCB, research suggests that organizational change or turbulence was related to increases in employee feelings of a PCB (Lo and Aryee, 2003, Turnley and Feldman, 1998). According to affective events theory, daily affect states have an impact on work attitudes (Luo and Chea, 2018, Weiss and Cropanzano, 1996). Since affective events have a lagging effect on mood (Beal and Ghandour, 2011, Braukmann et al., 2018), the pandemic-related workplace disruptions may cause negative affect to accumulate over time. Workers with a strong negative affect are likely to experience a negative attitude based on the condition of reneging during workplace disruptions. This leads us to propose the importance of workplace disruption on a PCB.

H1: Workplace disruption increases reported feelings of a psychological contract breach.

2.3. Felt mistrust

Trust is the ability to rely on the good intentions of another. When employees feel trusted, they reciprocate by improving their performance and organizational citizenship behavior (Lester & Brower, 2003). This positive interaction is theorized by social exchange theory, which proposes that when offered trust by the employer, employees will reciprocate with improved performance and positive extra role behaviors. This perceived trust will also lead to positive employee outcomes (Zheng, Hall, & Schyns, 2019). Employee feelings of being trusted by their supervisors, termed felt trust, also influence their workplace behaviors and attitudes (Salamon & Robinson, 2008). Felt trust may be a more direct influence on employees’ attitudes and behaviors than supervisor actual trust (Zheng et al., 2019). These feelings of being trusted come from the behavioral cues of their supervisors (Bernstrøm & Svare, 2017) and is inferred by the employee who observes their supervisor’s attitudes and behaviors (Zheng et al., 2019). “Perceptions of an individual’s trustworthiness fuel the attribution process that leads to either trust or distrust” (Lester & Brower, 2003, p. 18).

When faced with the COVID-19 pandemic health and safety directives established by local and state governments, many organizations promptly shifted employees to a work from home schedule. Employees’ working conditions, job duties, and work schedules changed in unexpected ways. The shift to a virtual workplace was accomplished both quickly and without much preparation for supervisors who may have had little or no training or experience with supervising distantly located employees. When managers are unable to directly observe employee performance, as may be the case with a virtual work schedule, there is often a fear by supervisors that employees may decrease their task-focused behavior (Whitener, Brodt, Korsgaard, & Werner, 1998). This may lead to a response by managers to increase monitoring and control, leading to a loss of felt trust by employees (Sitkin & Roth, 1993) and employee disappointment in the supervisor-subordinate relationship. Correspondingly, employee reactions may range from lower morale to opportunistic behavior, as the employee retaliates to the perceived excessive control. While supervisors may have increased formal control measures as a way to improve the trust they felt toward their employees, such measures instead may have led to increases in felt mistrust by the employee (Sitkin & Roth, 1993).

In a test of the control/trust relationship, Haesevoets et al. (2019) studied the use of the carbon copy (cc) function on email and its relationship to increases in feelings of mistrust. They found that the use of cc was perceived as a form of monitoring and control and that the increased use of cc was related to decreased felt trust. Similarly, Bush, Welsh, Baer, and Waldman (2020) found that increased monitoring (for unethical behavior) reduced trust and led to corrosion of the leader/follower relationship. They further found that the increased monitoring and reduced trust were related to increases in undesired outcomes like reduced organizational citizenship behavior and greater counter-productive workplace behaviors. Thus, although supervisors may feel it necessary to increase monitoring and control to improve their trust levels, their closer monitoring and control may cause the side effect of employees feeling mistrusted by their supervisors (Bernstrøm and Svare, 2017, Whitener et al., 1998).

In addition, mistrust feeds further mistrust because of how ambiguous behaviors are interpreted, setting up a self-fulfilling prophecy of increased feelings of mistrust and behaviors which counter increases in trust (Simons & Peterson, 2000). In the same way mistrusting behaviors invite feelings of mistrust, supervisors’ trusting behaviors enhance employees’ feelings of felt trust. When a supervisor delegates responsibilities, provides additional resources to the employees, seeks help and advice, and strengthens procedural justice, their employees are likely to feel more trusted by them (Byun et al., 2017, Lam et al., 2013). Trusting behaviors show the supervisors’ willingness to take risks on employees’ potentially reduced performance. During the pandemic-induced lockdown period, the shift to work from home was triggered as an emergency response. Although there might be a need to adjust other organizational arrangements around the employees’ work to ensure effective work performance, these arrangements were not proactively addressed in this situation. When employees’ job duties increased without additional support, work conditions varied with limited opportunities to report emerging constraints, and working schedules become uncertain but met with insufficient autonomy, the supervisors’ trusting behaviors are less likely to be observed by the employees.

With increased support from the organizations and the supervisors, employee concerns may have been reduced. However, supervisors themselves were loaded with additional burdens and suffered similar workplace disruptions as did their employees. Employees were more likely to receive additional job tasks with a lack of consideration for their home conditions, and thus less support from the supervisors. Meanwhile, as people around them were losing their jobs and incomes (https://www.bls.gov), employees may have become worried about the consequences of refusing additional demands from the organization. The supervisors’ constrained abilities to demonstrate their trusting behaviors, combined with the employees’ increased needs for such trusting behaviors, and employee hesitation to repair the relationship with their supervisors, were likely to contribute to decreased feelings of felt trust from the supervisors.

The psychological contract is based on a social exchange between employer and employee and “trust is the essence of social exchange” (Robinson, Kraatz, & Rousseau, 1994, p. 139). It is not surprising, therefore, that various measures of trust can act as both the antecedent and consequence of a PCB. Robinson (1996) investigated the intertwined relationship between trust in the organization and a PCB, using a longitudinal survey design. Results suggest that organizational trust is both the antecedent and the consequence of a PCB, so that loss of trust leads to a PCB, which in turn results in further erosion of trust. The revolving process reflects a vicious cycle towards an unhealthy employment relationship. Given this research and theory, we propose the following hypotheses.

H2: Workplace disruption increases reported employee felt mistrust.

H3: Felt mistrust mediates the effect of work disruption on a psychological contract breach.

2.4. Work to life conflict (WLC)

Work to life conflict (WLC) refers to “a particular type of inter role conflict in which pressures from the work role are incompatible with pressures from the family role” (Thomas & Ganster, 1995, p. 7). While recognizing that conflicts between work and life roles can be either work interference with life and life interference with work (Boswell & Olson-Buchanan, 2007), our discussion emphasizes work interference with life as we focus on the nature of employees having to work from home. Although a work from home schedule gives the impression that it will lead to flexibility and lower levels of work to life conflict (van der Lippe & Lippényi, 2020), research suggests that that may not be the case (Russell, 2009). Instead, the level of work to life conflict related to a work from home schedule appears to be contextual (van der Lippe & Lippényi, 2020). It is our contention that the sudden and unplanned change to a work from home schedule as a response to COVID-19 pandemic health and safety directives is a context that may be related to increased levels of WLC.

WLC results from three sources: behavior, time, and strain (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). A behavior conflict may occur if the individual is unable to switch behaviors to match the appropriate role. For example, in a business role, an individual may be expected to be assertive or demanding. While in a family role, the individual may be expected to be caring or accommodating. Jachimowicz, Cunningham, Staats, Gino, and Menges (2021) suggest that the commute to and from work may be an opportunity for individuals to transition into the appropriate role. Without a clear boundary, like a commute, between work and home roles, a behavior role conflict may be an additional source of WLC with a work from home schedule.

Given that time is a limited resource, time spent on work automatically reduces time available for other roles and vice versa. The workplace disruption which sent employees home to work, also sent home most, if not all, other family members. The closures of restaurants, hair salons, schools, childcare centers, etc. limited the opportunity for employees to outsource household responsibilities, adding to the time-conflict experienced. The increasing time demanded by family and home exposed the limitation of an employee’s resources, leading to negative attitudes. Ongoing, these negative attitudes may accumulate and lead to a perception of elevated WLC.

Strain, caused by work or home stressors, interferes with the ability of the employee to fulfill both work and home roles (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). From a work perspective, the change in the work environment itself is a stressor. This abrupt change of work location to home leads to uncertainty with regards to the boundaries between work and family (Ashkanasy et al., 2014, Carnevale and Hatak, 2020). Strain increases because of the ambiguity associated with the sudden and unplanned shift to a work from home schedule. The lack of preparation for such a transition can lead to a discrepancy between the expectations of supervisors and employees for permitted boundary-crossing behaviors. What supervisors and coworkers may see as reasonable expectations, such as frequent synchronized meetings and short deadlines, can be perceived as boundary control strategies by the employee (Perlow, 1998). It is our proposal that work to life conflict is increased due to the workplace disruption related to a move to a work from home schedule.

For employees working from home, frequent boundary-crossing events tend to be stressful and emotionally disturbing. Braukmann et al. (2018) surveyed 153 German employees across various industries, who took a smaller half of their work home. They found that, although the participants had the flexibility of the work hours, they were often bothered by negative affective events such as WLC and technical problems at home. While the sample in Braukmann et al. (2018) study was on their routine working schedule, the pandemic-induced work from home schedule represents much more chaotic disruptions. Consequently, the employees are likely to experience more stressful events, elevated strain, and negative job attitudes (Fuller et al., 2003). Therefore, we predict intensified feelings of WLC as a result of the frequent occurrence of boundary-crossing events during the pandemic.

In addition, we propose that increases in felt mistrust will mediate this relationship because of the constrained relationship between employee and supervisor. The inflexibility of employer demands, such as scheduled meetings and telephone calls directly impacts the freedom employees have to organize their work-focused behaviors in a way that also meets their home obligations. Ashkanasy et al. (2014) suggest that frequent disruptive episodes cause negative emotions. As a result, employees engage in territorial behaviors to build and protect their individual spaces. In a work from home situation, the employer’s control practices may accelerate employee attempts to strengthen the territorial boundaries between work and life. The bolstered boundaries further make invasive events more salient, which may then reinforce feelings of mistrust, forming a vicious cycle that highlights the conflict between work and life. Thus, we propose that employer expanded control measures reduce the flexibility of the work from home schedule, erode felt trust, and lead to increased employee feelings of WLC.

H4: Workplace disruption is positively related to increases in reported feelings of work to life conflict.

H5: Felt mistrust mediates the relationship between workplace disruption and reported feelings of work to life conflict.

Organizational policies that help employees balance demands between work and personal life are often part of the perceived obligations in the psychological contract (Kraak et al., 2017, Sturges and Guest, 2004). In addition, Matthews and Toumbeva (2015) argue that without direct supervisor involvement, employees are unlikely to benefit from family friendly organizational policies. Yet, during the COVID-19 pandemic, supervisors themselves were subjected to the same disruptive events, the same added job duties, and the same role conflict as their employees. Under such circumstances, spending time and energy providing discretionary family friendly modifications may be beyond their personal resources. Moreover, because supervisors are isolated and only virtually connected, they lack the means to observe the problems employees may experience or the ability to provide proper solutions to such problems. Hence, employees caught in increasing WLC during the transition to a work from home schedule may not receive support according to the organizational policies that do exist. As the organizations fail to fulfill its obligations through their supervisors, employees’ feelings of a breach in their psychological contracts may increase, leading to our next hypothesis.

H6: Reported feelings of work to life conflict mediates the relationship between workplace disruption and employee feelings of a psychological contract breach.

Although organizational disruption may lead to broken promises, the employee may not necessarily equate those broken promises with feelings associated with a breach of psychological contract. Instead, research and theory suggest that the employee may find some discrepancies more acceptable than others (Hofmans, 2017, Schalk and Roe, 2007). Given that organizations were required to shift employees to a work from home schedule due to government restrictions, that disruption, in and of itself, is one in which employees are more likely to judge as an acceptable discrepancy in the psychological contract. Instead of a breach, the psychological contract may have been adjusted in an employee’s view to accommodate the novel nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. The key that turns the discrepancies in a psychological contract into a perceived breach, is the state of trust. Schalk and Roe (2007) argue that employment relationships based on trust are more likely to have wider acceptance of psychological contract discrepancies than relationships without such trust. Thus, if employees feel trusted by their organization, they are more likely to accept discrepancies in the psychological contract without feelings of a PCB. Without these feelings of trust, employees are more likely to view discrepancies as unacceptable.

On the other hand, as individual employees are sent home to complete assigned tasks, despite being ill-prepared, they may well expect support from their supervisors. This would be the time to use the credit of trust so that their supervisor would demonstrate empathy when home obligations interfered with previously established work hours. Yet, the signal from supervisors may suggest a rejection of the previously established credit of trust. Although employees may rationally acknowledge the necessity of the inconvenience, their affective states may be impacted by the daily evidence of mistrust and WLC, leading to doubt the sincerity of their employers in their attempt to fulfill the psychological contract. To test this proposition, we consider both WLC and trust as possible mediators in the relationship between organizational disruption and a PCB. It is our contention that a work from home schedule is considered an unacceptable breach of the psychological contract when such a schedule unduly increases feelings of mistrust and WLC.

H7: Felt mistrust and reported feelings of work to life conflict mediate the relationship between workplace disruption and employee feelings of a psychological contract breach.

2.5. Coping as a contingency variable

Given that strain is an important determent of work to life conflict (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985) and the related strain literature that speaks to the positive effect of coping mechanisms on strain (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980), we incorporate coping as a moderator in our model studying the relationship between WLC and PCB. “Coping is defined as the cognitive and behavioral efforts made to master, tolerate, or reduce external and internal demands and conflicts among them” (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980, p. 223). Problem-focused coping mechanisms are situation-specific and aim to change or manage the difficulty an individual faces. In order to reduce work to life conflict, employees are generally able to utilize a variety of coping mechanisms in an attempt to alleviate the role conflict experienced.

In contemporary research, PCB is often viewed as the trigger (independent variable). As such, there are few studies investigating how coping strategies may affect employees’ perception of PCB (as the dependent variable). One such article that did consider the effects of coping on PCB was Bankins (2015). Bankins (2015) found that coping actions that facilitate the sense making of an initial breach may sometimes bring repair to the breach, forming a process of evolution of the psychological contract. This perspective, however, does not address preventive behavior that are provoked by other factors (e.g., WLC) causing increase of PCB perception.

Similarly, research addressing the relationship between WLC and PCB does not cover specific coping strategies that may reduce the impact of WLC on PCB, especially in the work from home scenarios. Discussions on coping strategies in the WLC literature are mainly focused on stress coping, with some articles emphasizing family support (Akanji et al., 2020, Matsui et al., 1995) and other psychological processes (Duhachek, 2005; Jin et al., 2014, Rotondo and Kincaid, 2008). Given that supervisors play a critical role in employees perceptions of WLC (Matthews & Toumbeva, 2015), we believe that coping strategies that are focused on supervisors will need to be identified in this study.

Some traditional coping mechanisms aim to reduce family demands and others aim to reduce work demands in order to achieve the balance needed to reduce WLC. For example, employees might set up temporal boundaries between work and life so the two do not mix at the same time. Or employees can take a few hours to relax when stress mounts and leave some home responsibilities to the partner or service institutions. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, many traditional family-focused employee coping resources were greatly limited due to government guidelines that restricted business openings, social activities, and extended family interactions. As such, we investigate problem-focused coping strategies that aim to reduce employers’ boundary-crossing behaviors. As employees actively attempt to resolve WLC through coping, they may find ways to gain understanding and support from their supervisors, ease the tension within the employment relationship, and lessen the severity of a PCB. Matthews and Toumbeva (2015) suggest that the perception of a family-supportive organization is a result of family-supportive supervision. Employee coping strategies which invite supervisors to engage in family-supportive supervision, may lead to a positive perception of organizational support for maintaining the psychological contract and a commitment to reduce WLC.

H8: Coping strategies moderate the relationship between work to life conflict and employee feelings of a psychological contract breach, such that increased use of coping strategies would reduce the feelings of PCB, even at higher levels of WLC.

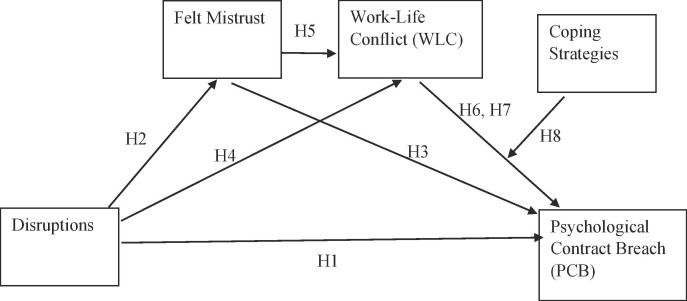

Fig. 1 illustrates our research model and the hypothesized relationships between workplace disruption, felt mistrust, work to life conflict, coping strategies, and a psychological contract breach.

Fig. 1.

Research Model: The Relationship between Disruption, Felt Mistrust, WLC, Coping Strategies and PCB.

3. Study 1 methodology

We first tested the hypothesized impact of workplace disruption on PCB through felt mistrust with an experimental design. An experimental design allows us to manipulate one type of disruption to isolate the potential causal effects of felt mistrust.

3.1. Sample and procedures

Undergraduate students enrolled in five classes at a university located in the southeastern United States were offered an opportunity to complete a voluntary and anonymous online experimental study for ½ extra credit point. The self-administered study was presented via Qualtrics. Approval was granted from the authors’ Institutional Review Board. In total 177 students were offered the extra credit via email and 133 completed the study, for a 75% response rate. Respondents (N = 133) were between the ages of 18 and 45 (M = 21.49; SD = 3.97), with an equal distribution of sex (male = 67).

A randomly assigned two cell experimental design was created in order to test hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. One possible type of workplace disruption was manipulated by asking the respondent to imagine themselves in the described job scenario as a member of a human resource department of a large company. The scenario in the low-disruption group (Cell 1) presented a workplace situation where the job was shifted to a work from home schedule where very little else about the job experience had actually changed. The scenario in the high-disruption group (Cell 2) presented the same job shifting to a work from home schedule but added information that the organization had instituted several supervisory control mechanisms (see Appendix).

A manipulation check item and an open-ended question were presented immediately following the scenario, asking respondents to first rate and then describe the workplace presented. Respondents then answered questions probing their anticipated level of a PCB and felt mistrust from the supervisor described in the scenario.

3.2. Measures

Unless otherwise noted below, all items were measured on a five-point scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Manipulation Check. As a manipulation check, respondents were presented with the following question: “Considering everything, how much has the HR director's management style changed since working from home?” Answers ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal). Following this item, an open-ended question asked: “Please explain your reason for this view.” Respondents in cell 2 (n = 65), reported significantly greater change (F = 4.18; p < .05) in the supervisor's management style when compared with cell 1 (n = 68), an indication that the manipulation of workplace disruption due to increased supervisory control was successful.

Psychological Contract Breach (PCB). PCB was measured as a five-item scale designed to determine the respondents’ “perceptions of how well their psychological contracts had been fulfilled by their organizations” (adapted from Robinson & Morrison, 2000, p. 534). A sample item is “Almost all the promises made by my organization during recruitment have been kept so far” (reversely coded). We adapted two negatively worded items by reversing to positive phrases (item 4: changed not received to received and item 5: changed broken to kept). All items were reverse scored so that higher scores are an indication of a PCB. For Study 1, α = 0.93, which is consistent with reported levels of internal reliability of 0.92 (Robinson & Morrison, 2000).

Felt Mistrust. Felt mistrust was measured as a four-item scale designed to determine if the respondents’ feel that their supervisor’s trust in them has decreased since they were moved to a work from home schedule (inspired by and adapted from Salamon & Robinson, 2008). We adapted the items by reversing trust to mistrust, changing the tense, and adding the phrase “Since moving to a work from home schedule” at the start of each statement. A sample item is “Since moving to a work from home schedule, my supervisor’s trust in me has decreased.” For Study 1, α = 0.94.

4. Study 1 results

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using the axis factoring analysis method with varimax rotation extracted two factors explaining a total of 73% of the variance of the measured variables. Consistent with the designed instruments, the five PCB items loaded on one factor and the four felt mistrust items loaded on the other factor, with all loadings at or above 0.80. The alternative loadings were at or smaller than 0.21, indicating no cross-loading issues.

Next, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to further test the validity of the measurements. The indices were above the recommended threshold (Byrne, 2016, Tabachnick et al., 2007), showing a good fit of the data to the hypothesized model. Specifically, fit indices were above 0.90 (GFI = 0.96, NFI = 0.97, CFI = 0.999). Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was below 0.08 (RMSEA = 0.02). Normed chi-square (χ2/df) was below 2 (χ2 = 27.54, χ2/df = 1.06).

The average variance extracted (AVE) of PCB and felt mistrust were 0.74 and 0.80, respectively, which was above the threshold of 0.5. And the composite reliability (CR) of the two variables were 0.93 and 0.94, which was above the threshold of 0.7, indicating acceptable convergent validity. The square roots of AVE (0.86 and 0.89) were greater than the correlation (r = 0.31, p < 0.01), indicating adequate discriminate validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Consequently, the factor scores of the latent variables in CFA analysis were imputed for hypotheses testing.

To detect potential issues with common method bias, we employed the unmeasured latent variable approach suggested by Podsakoff, MacKenzie, and Podsakoff (2012). In addition to the two-factor CFA model described above, we ran a second model with an added unmeasured common latent factor. The AIC (Hu & Bentler, 1995) and CAIC of the two models were compared. Both indices of the original two-factor model (AIC = 65.54; CAIC = 139.46) were smaller than those of the common latent factor model (AIC = 76.22; CAIC = 177.26), indicating better fit of the original model. Thus, it is unlikely that common method bias presents a substantial problem in Study 1.

We used ANOVA in order to test hypotheses 1, 2, and 3. The ANOVA results show that the respondents in the high-disruption condition (Cell 2 M = 2.10, SD = 0.73) reported significantly higher PCB than those in the low-disruption group (Cell 1 M = 1.79, SD = 0.80; F[1, 131] = 5.64; p < .05; η2 p = .04), showing support for Hypothesis 1, which tested the main effect of work disruption on PCB. Similarly, the level of felt mistrust in the high-disruption group (Cell 2 M = 2.59, SD = 1.06) was significantly greater than the level of felt mistrust in the low-disruption group (Cell 1 M = 1.99, SD = 0.94) in the ANOVA test (F[1, 131] = 12.10; p < .01; η2 p = .09). This provided support for Hypothesis 2, that work disruption provokes felt mistrust.

Hypotheses 3 proposed that felt mistrust acts as a mediator between disruption and PCB. In order to test H3, we ran a regression analysis on 5,000 bootstrap samples using PROCESS v3.3 macro Model 4 in SPSS (Hayes, 2017). First, the total effect of workplace disruption on PCB was significant and positive (b = 0.32; p < .001), further supporting Hypothesis 1. Next, the effect of workplace disruption on felt mistrust was significant and positive (b = 0.60; p < .01), consistent with the proposed relationship in Hypothesis 2. Finally, the indirect effect of felt mistrust between disruption and PCB was significant and positive (effect index = 0.13; 95% CI = [0.03, 0.27]). Meanwhile, the direct effect of disruption on PCB became nonsignificant when the indirect effect was counted for. Thus, Hypothesis 3 of the mediation effect of felt mistrust was supported.

5. Study 1 discussion

In Study 1, we tested the hypothesized impact of workplace disruption on PCB through felt mistrust with an experimental design. The results suggest that administrative disruptions along with mandatory changes in employee work arrangements increased perceived felt mistrust from the supervisor, which in turn triggered feelings of a PCB. As some respondents in the high-disruption group pointed out in answering the manipulation check question, “… Having the screen monitored and being home alone is much different and can become daunting at times.” “It feels that the HR Director does not trust employees working from home. It feels like you are being constantly watched for doing what you are being paid for. While I understand the rationale for this, from the employee standpoint, it is not the same job. I would not like to work for someone like this.” The evidence fully supported the rationale and predictions of Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3.

While the experiment established the causal effect of work disruption due to increased monitoring from a supervisor, the scenarios do not capture the complexity of all workplace disruptions employees may experience in the real world during the pandemic. First, the causes of the disruptions can be many and involve changes beyond increased monitoring from a supervisor, including disruptions in job duties, working conditions, and work schedules. These various possible changes may divert employees’ attribution to the disruptions and contribute to felt mistrust. In addition, employees may take contextual factors of how the pandemic is impacting the overall nation into consideration and develop empathy toward employers. In cases like this, the perception of a PCB may be partially dismissed. Moreover, WLC is one of the focal concerns in the sudden shift to a work from home schedule, yet study 1 did not consider this aspect. In order to test the mediation effect between work disruption, felt mistrust, and a PCB (Hypotheses 4, 5, 6, and 7), explore the usefulness of coping strategies (Hypothesis 8), and address the concerns above about contextual factors, we conducted a field survey, which is reported below in Study 2.

6. Study 2 methodology

6.1. Procedures

A self-administered and anonymous survey was designed to measure employee job attitudes in response to COVID-19 workplace disruptions in test of the Hypotheses. Approval was granted from the authors’ Institutional Review Board. Respondents were recruited from a crowdsourcing marketplace to participate in the online survey. In order to meet the criteria for participation, respondents must have been working from home either part or full-time. An attention check question was presented in the middle of the questionnaire to enhance data quality.

Replies were received from 296 respondents, however not all respondents met the minimum criteria of working from home either part or full-time (n = 15). We then further reviewed the responses for one short answer item to ensure good quality answers. For the short answer item, we asked: “Thinking about your life right now, what is the largest concern you are facing?” An example of a passing answer is: That I may lose my job and wouldn't be able to pay my bills. Examples of a failing answer include: yes, good decision and It was a pleasure to be in your statistics class this semester. Respondents who failed this additional check (n = 42) were also excluded from further analysis. Ad hoc analysis reveals that, while the removal of these responses enhanced the validity of the data, it does not change the directions and significance of the findings.

To capture the general impact of the pandemic, we asked two student research assistants to code the 239 responses to the above question about the largest concern in life at the time (several months into the lockdown period; ICC = 0.77, p < .001). On average, about 35.0% of the respondents were nervous about financial issues, 23.2% were worried about the health of themselves and families, fearing infection with COVID-19, and 10.2% listed job security as their biggest concern. These top concerns reflected the anxiety the respondents experienced as the result of the abrupt changes in their lives.

6.2. Sample

Respondents (N = 239) were, on average, 36 years old (SD = 10.28) with an average tenure of 6.31 years (SD = 5.23) with their current organization. Respondents indicated they worked in the following industries: service (44%), education/government (15%), manufacturing (22%), or other (19%). They were primarily male (60%), working full-time (89%), had a college or graduate degree (82%), and had minor children in the home (52%).

6.3. Measures

Unless otherwise noted below, all items were measured on a five-point scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) and are displayed in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Measures and CFA Factor Loadings (Study 2; N = 239).

| Variables/Itemsa | Factor Loadings (CFA) | Cronbach Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| Psychological Contract Breach (PCB) | 0.84 | |

|

0.74 | |

|

0.77 | |

|

0.70 | |

|

0.66 | |

|

0.74 | |

| Disruption | 0.75 | |

|

0.55 | |

|

0.77 | |

|

0.81 | |

| Felt Mistrust | 0.93 | |

|

0.86 | |

|

0.86 | |

|

0.85 | |

|

0.91 | |

| Work to life conflict (WLC) | 0.88 | |

|

0.76 | |

|

0.80 | |

|

0.81 | |

|

0.87 | |

|

0.79 | |

|

0.79 |

Coping strategies was not included in the factor analysis because it was measured as a summed construct. Items of this variable are listed in the section of Measures.

Disruption. In creating the measure for workplace disruption, we attempted to capture the day-to-day job-related changes caused by the switch to work from home during the lockdown period in the COVID 19 pandemic. Employees’ job duties, working conditions, and work schedules changed in unexpected ways. First, job duties were likely to change, as people could not have face-to-face interactions, and surviving employees may have to take additional workload after company furloughs and layoffs. Second, working conditions are often tied to a specific physical location and are also related to established relationships with co-workers and supervisors. Moreover, although the work schedule was enabled by technology, the work from home schedule led to potential disruptions when family or home responsibilities demand attention during the usual workday. These disruptions are likely to affect the status quo of employment obligations and have implications to the perception of psychological contract breach (Chi et al., 2021, Krausz et al., 2000, Turnley and Feldman, 2000).

Disruption was measured as a three-item scale designed to determine the perceived level of disruption respondents faced in their job and work conditions due to the COVID-19 pandemic. These measures were developed for this study. The items were measured on a five-point scale, from 1 (not at all) to 5 (a great deal) and measured perceived disruption in job duties, working conditions, and work schedule. A sample item is “How much were your work conditions disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic?” For Study 2, α = 0.75.

Felt Mistrust. Felt mistrust was measured with the same four-item scale as in Study 1. For Study 2, α = 0.93.

PCB. PCB was measured with the same five-item scale as in Study 1. For Study 2, α = 0.84.

Work to life conflict (WLC). Work to life conflict was measured as a six-item scale designed to determine the respondents’ overall reported feelings that their current jobs interfere with their lives. The items were developed by Thomas and Ganster (1995). One item was slightly adapted to accommodate the work from home environment. The original wording “After work, I come home too tired to do some of the things I’d like to do” was presented as “After work, I am too tired to do some of the things I'd like to do.” For Study 2, α = 0.92, which is consistent with reported levels of internal reliability of 0.88 (Thomas & Ganster, 1995).

Coping Strategies. Since various coping strategies are supplementary to, rather than reinforcing each other, the variable is more meaningful when measured as a summed construct based on the overall frequency of the usage of five strategies. Coping is not a static process, but instead requires multiple techniques in order to best cope with problems as they evolve. It may be that, given the circumstances, one coping strategy is more or less effective than another, requiring the individual to shift among several coping strategies (Folkman & Lazarus, 1980). Therefore, coping is better measured as a compilation of multiple methods to best fit both the situation and individual facing disruptions (see Oakland & Ostell, 1996 for a review of measuring coping).

We were unable to find relevant existing scales to measure the coping strategies of remote workers in the extent literature. As such, we developed new items inspired by anecdotal articles (Gallow, 2020, Torres, 2020, Vasel, 2020). These coping strategies address various aspects of remote work management and can be used separately or in combination. They reflect the effort to ease the maladaptation of new communication styles and the feedback loop by offering compatible ways of communicating with supervisors. Respondents were presented with five coping strategies and were asked to indicate their use of each of the different coping strategies in response to supervision during a work at home schedule. These items are (1) “When I work remotely, I made it clear to my immediate supervisor that micromanaging is counter productive for me”, (2) “When I work remotely, I actively report to my immediate supervisor”, (3) “When I work remotely, I do not change my work arrangement even when my immediate supervisor tries to monitor me often”, (4) “When I work remotely, I communicate with my immediate supervisor in their preferred way”, (5) “When I work remotely, I choose my words carefully when communicating with my immediate supervisor”. The responses of each participant were aggregated to form the single-item measure of coping strategies.

7. Study 2 results

We first performed EFA to investigate the factorial structure of the data. Using the principal axis factoring analysis method with varimax rotation, four factors representing PCB, disruption, felt mistrust, and WLC were extracted as predicted, albeit two items were removed from WLC and one item was removed from disruption due to cross loading problems. All loadings of the remaining items were above 0.69 and were at least twice as strong as those with any alternative factors, indicating reasonable construct validity (Hinkin, 1998).

Next, we conducted CFA to test the validity of the measures. The hypothesized model achieved acceptable model fit (Byrne, 2016), with fit indices above 0.90 (GFI = 0.93, NFI = 0.93, CFI = 0.98), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below 0.08 (RMSEA = 0.04). The model Chi-Square was 182.54, and normed chi-square (χ2/df) was 1.42, well below the recommended level of 2 (Tabachnick et al., 2007). Except for one item of PCB (0.66) and one item of disruption (0.55), the factor loadings of all other items were above 0.70. This provided further evidence of construct validity. Table 1 provides the measures and factor loadings of the variables in the CFA model for Study 2.

A comparison of nested models was performed to evaluate whether the hypothesized model accurately estimates the true reliability of the data (Graham, 2006). Specifically, the hypothesized model was compared with the tau-equivalent model, which restricts all measures of a factor to have equal loadings, as well as the parallel model, which further restricts the residual variances of the measures to be the same. The fit indices suggested that the hypothesized model (GFI = 0.92; CFI = 0.98; RMSEA = 0.042) was superior to the tau-equivalent model (GFI = 0.91; CFI = 0.97; RMSEA = 0.05) and the parallel model (GFI = 0.90; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.05). In addition, the likelihood ratio test results indicated that the hypothesized model had a significant better fit than the tau-equivalent model (Δχ2 (14) = 39.53, p < .001) and the parallel model (Δχ2 (28) = 67.29, p < .001).

In addition, as shown in Table 2 , values of the AVE were above 0.50, and values of the CR were above 0.70, indicating acceptable convergent validity. The square root of AVE was greater than the maximum number of the correlations, suggesting that the discriminate validity of the measured variables was acceptable (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). As a result, the factor scores of the latent variables were imputed from the CFA model.

Table 2.

Correlations and Validity Tests of the CFA Model (Study 2; N = 239).

| CR | AVE | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Disruption | 0.76 | 0.51 | 2.97 | 0.85 | .72a | |||

| 2. Felt Mistrust | 0.93 | 0.76 | 2.96 | 1.21 | 0.64*** | 0.87 | ||

| 3. Work to life conflict | 0.92 | 0.65 | 2.90 | 0.95 | 0.72*** | 0.74*** | 0.80 | |

| 4. PCB | 0.84 | 0.52 | 1.80 | 0.60 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.16* | 0.72 |

**p < .01.

Diagonal of Table 2: The square root of the average variance extracted (AVE).

p < .05.

p < .001.

Similar to Study 1, we used the unmeasured latent variable approach to further test for common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2012). Comparing the AIC and CAIC of the original four-factor CFA model with those of the model with the unmeasured common latent factor, both indices of the original model were smaller (AIC = 266.54 vs. AIC = 270.35; CAIC = 454.55 vs. CAIC = 538.94), representing a better fit for the four-factor model. Thus, common method bias was not detected in Study 2.

7.1. Test of the research model

A regression-based bootstrapping technique (Hayes, 2017) was used to test the hypothesized relationships between the constructs of workplace disruption, felt mistrust, WLC, and PCB. All analyses were performed using PROCESS v3.3 for SPSS on 5,000 bootstrapped samples with confidence intervals of 95%. Hypotheses 1, 2, and 3 suggest that workplace disruption increases employee feelings of a breach in psychological contract, with felt mistrust mediating this effect. We tested this set of hypotheses with macro Model 4. Findings suggest that disruption significantly increased felt mistrust (b = 1.03; p < .001), which supports Hypothesis 2. However, neither disruption nor felt mistrust were found to have a significant impact on PCB. Likewise, the indirect effect of felt mistrust was insignificant. Thus, Hypothesis 1 and Hypothesis 3 were not supported. These results only partially reinforce the findings in Study 1.

Next, Hypotheses 4 and 6 suggested that disruption increases WLC, which mediates the impact of disruption on PCB. Again, variables were entered in macro Model 4, and the results showed that there was a significant relationship between disruption and WLC (b = 0.89; p < .001). Moreover, WLC had a significant and positive effect on PCB (b = 0.15; p < .05). Further, the indirect effect of disruption on PCB through WLC was significant with an index of 0.13 (CI = [0.005, 0.25]). Thus, Hypotheses 4 and 6 were supported.

Hypothesis 5 proposed a mediating role of felt mistrust between disruption and WLC. Results from a macro Model 4 indicate that both disruption (b = 0.54; p < .001) and felt mistrust (b = 0.34; p < .001) significantly increased WLC. Moreover, the indirect effect of felt mistrust was significant (effect index = 0.35; CI = [0.24, 0.48]). Thus, Hypothesis 5 was supported.

Hypothesis 7 suggested that there is a serial mediating effect so that disruption alters PCB through felt mistrust and WLC. We employed macro Model 6 with two mediators to test this hypothesis. Besides the significant relationships between disruption, felt mistrust, and WLC, WLC had a significant impact on PCB (b = 0.15; p < .05). There was a significant indirect effect of disruption on PCB through WLC, where the index value was 0.09 (CI = [0.006, 0.17]). Moreover, the serial mediation effect of disruption on PCB through felt mistrust and WLC was significant, with the index value of 0.06 (CI = [0.004, 0.13]). This provided support for Hypothesis 7.

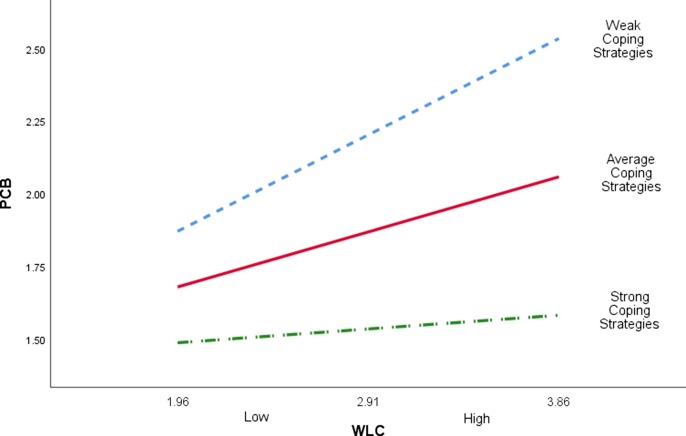

Hypothesis 8 proposed that coping strategies moderate the relationship between WLC and PCB, such that increased use of coping strategies would reduce the feelings of PCB, even at higher levels of WLC. We employed macro Model 87 to test this hypothesis. The results showed that the interaction effect of WLC and coping strategies had a significant and negative impact on PCB (b = -0.04; p < .001). The indirect effect index is −0.02, with a confidence interval between −0.04 and −0.01. Fig. 2 illustrates the simple slope analysis of the moderated mediation effect of coping strategies. Specifically, when coping strategies were used rarely (i.e., 1 SD below the mean), WLC significantly increased the feelings of a breach in the psychological contract. However, if the employee reported increased use of coping strategies (i.e., 1 SD above the mean), the impact of WLC on PCB became insignificant. Thus, Hypothesis 8 was supported.

Fig. 2.

Simple slopes of the relationship between Work Life Conflict (WLC) and Psychological Contract Breach (PCB) at the levels of 1 SD below, at, and 1 SD above the mean of coping strategies.

8. General discussion

This study examines the workplace disruptions related to the switch to a work from home schedule and investigated the impact of these disruptions on a breach in the psychological contract through the mediation effects of employee felt mistrust and work to life conflict. The research model was tested, and several hypotheses were supported. Although the direct effect of the environmental disruption on PCB was inconclusive, the indirect effects were significant. First, the disruptions of switching to a work from home schedule increases WLC, which mediates the effect of work disruption on PCB. The role of WLC as a mediator was not established in the previous literature. Our findings, that WLC mediates the effect of work disruption on PCB, highlight the importance employees place on a smooth transition across the work-life interface as part of the psychological contract. This was the case even when the disruptions were not directly related to a PCB. Employees apparently placed the blame for the disruptions on employers when the disruptions provoked WLC. Moreover, it is interesting that perceived supervisor mistrust mediates the effect of workplace disruptions on WLC. This is worth noting since it highlights the importance of felt trust as a factor that leads to the attribution of disturbances in the employees’ personal life due to the intrusion of work and the organization.

Further, we found a serial mediation effect of disruption on PCB through felt mistrust and WLC. This finding partially illustrates the cognitive struggle that employees experience when feeling mistrust from their supervisors, which justifies employees’ feelings of a PCB. Our findings also indicate that the disruption of a switch to a work from home schedule in the context of a pandemic, although may have brought many difficulties to the employees, does not automatically result in a PCB. Rather, it is possible that the effect becomes significant as negative affective events accumulate over time. A demonstration of supervisor trust or support to sustain work-life balance may prevent a breach in the psychological contract despite the disruptive environment.

Finally, the increased use of coping strategies was found to mitigate the detrimental effect of disruption and felt mistrust on a PCB through WLC. The literature has not systematically investigated the function of the use of coping strategies by employees throughout the entire process of a PCB. Some researchers argue that coping makes a difference after the psychological contract is breached or violated (Bankins, 2015). In contrast, this study takes a fresh look into the interactions between employees and their immediate supervisors and found that employee use of a combination of coping strategies was effective in maintaining the psychological contract, despite the shock events related to the pandemic.

8.1. Practical implications

Our findings not only contribute to the literatures of PCB, WLC, and trust, but also shed light on what Human Resource departments and managers may do to reduce the potential for a PCB before the employee’s assessment of the status of their psychological contract. It is important that employees perceive that they have their supervisor’s support when facing PCB (Stoner et al., 2011, Zagenczyk et al., 2009). For example, with a sudden change in work arrangements, managers should pay attention to the vulnerability of trust in the relationship with employees and find ways to reconfirm the established trust. The work from home schedule changes the methods a manager might use to manage employee performance, which may necessitate additional management training (Pianese, Errichiello, & da Cunha, 2022). Employee feelings of felt mistrust may increase if managers change from quiet observation and casual face-to-face conversations to blunt explicit inquiries about performance or fail to provide support to accommodate disruptions of job duties, work conditions, and working schedules. Building a mutually agreed upon system of communication (Reimann, 2017) and reporting protocol may reduce the tension between a need for information on the side of the employer and a need for empowerment on the side of the employee.

For a successful work from home schedule, managers should respect the employees’ lives outside of work and help reduce the conflict between work and life (Alegre et al., 2016, Las Heras et al., 2015) by allowing flexible schedules and limiting mandatory synchronized collaboration. This is especially important when the abrupt change to a work from home schedule blurs the boundary between work and life. During a crisis, such a switch may be involuntary and under external stressors that also cause complications in the home life of the employees. Since each employee has a unique home situation to deal with, managers should be sensitive to individual employee needs by involving employees in participative decision-making (Ertürk & Vurgun, 2015). Further, active listening skills can be extremely important in managing employees working from home. This would permit open channels of communication (Stoner et al., 2011) and allow for employees to utilize various coping strategies. By listening actively, managers can learn to help their employees succeed, even when they cannot see the employees’ task related behaviors.

8.2. Limitations and directions for future research

This paper is not free from limitations, some of which call for future study. One essential reason we predict that felt mistrust would increase during a shock transition of the work environment is that supervisors are likely to respond to the sudden switch to remote management with micromanagement tactics, so as to replace information lost due to the lack of co-location with their employees. Study 1 tested this assumption and validated the prediction. This illustrated the dilemma facing the supervisors, who may have to choose between the loss of important information for supervision and the loss of a trusting relationship with their employees. Research in leadership and computer-based communication is suggested to provide further insight into this process and to uncover solutions that delivers the sense of care to the employees in the remote workplace (Gibson, 2020).

Unlike Study 1, Study 2 only confirmed the relationship between work disruption in general and felt mistrust. Notably neither disruption nor felt mistrust was strong enough to make significant direct impacts on PCB in Study 2. Although we did suspect that the complexity of the pandemic shock could mitigate these effects, future studies may continue to examine the attribution processes of the PCB and identify potential contingency factors that may moderate the perceptions of a PCB. Finally, there is limitation with the Study 2 sample, in that quite a few responses had to be eliminated to enhance the quality of the data. Although excluding the disqualified responses did not change the detected effects, it is nonetheless a point of concern. It would be very helpful if researchers were able to determine the reasons behind poor quality responses to better develop effective screening methods to recruit the right people for survey participation.

We found the affective events theory appealing in serving as the underlining mechanisms in understanding the impact of a switch in the work environment due to the pandemic. We believe the accumulative effect of a series of affective events is a powerful prediction of employees’ attitudes concerning their relationships with their supervisors and employers, especially in the work from home scenario where employees are physically and socially isolated. However, it is beyond the scope of this paper to find direct evidence for such an effect. It would be fruitful for future research to continue to examine the affective experiences of remote employees.

9. Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic found many companies unprepared when their employees were required to switch to a work from home schedule. While most managers and employees struggled to get their jobs done, the employment relationship may suffer from a breach in the psychological contract without being noticed by management. Although technology has evolved to convey much richer information, the severity of the disruption and the lack of co-location may still make it difficult to adequately communicate contextual information. Managers may not be aware of the employees’ perceptions of felt mistrust and a work to life conflict when trying their best to accomplish work related goals. This may result in an unexpected breach in the psychological contract and may potentially damage employee performance.

This paper depicts the effects of a workplace disruption scenario and reveals the path of how a shock in the work environment can trigger employee felt mistrust, intensify work to life conflict, and eventually cause a breach in the psychological contract. We contribute to the literature by establishing the serial mediation effect of felt mistrust and work to life conflict on the psychological contract breach, as well as identifying coping strategies that may alleviate the impact of the disruption. Managers should be cognizant of such concerns related to workplace disruptions and develop practices to prevent a disruption-induced breach in the psychological contract.

Author Note.

Baiyun Gong ID https://orcid.org/0000–0001-6842–0720.

Randi L. Sims ID https://orcid.org/0000–0001-5671–1045.

Both Study 1 and Study 2 received approvals as “exempt” from the IRB at Nova Southeastern University. Signed consent forms were waived as they would become the only link between the participants’ identities and their responses. Instead, the consent forms were posted as the first page of the study instruments, and the participants were free to enter the next page of the survey or exit at any time.

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Baiyun Gong: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Formal analysis, Methodology. Randi L. Sims: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Methodology, Data curation, Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Biographies

Dr. Baiyun Gong is an Associate Professor of Management at the H. Wayne Huizenga College of Business and Entrepreneurship at Nova Southeastern University. She received her Ph.D. from the Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business, University of Pittsburgh. Her research interests include career development, remote work, and social capital. She enjoys traveling, listening to the music, and learning about the new trends of information technology.

Randi L. Sims is currently a Professor of Management for Nova Southeastern University, located in Fort Lauderdale, Florida. She obtained her doctorate degree in Business Administration from Florida Atlantic University. Her teaching and research interests lie in the fields of ethical decision making, organizational behavior, and academic dishonesty. She has published in Journal of Business Ethics, Business & Society, International Journal of Stress Management, Educational and Psychological Measurement, International Journal of Value Based Management, and Journal of Psychology among others.

Appendix.

Scenarios.

Imagine yourself in the following job and answer the questions that follow.

As a member of the HR department of a large corporation, your position is responsible for developing and facilitating an employee wellness program. This includes posting a weekly online newsletter, holding a monthly employee seminar, and answering employee questions about general wellness topics. You have been in this position for quite some time and feel confident in your ability to successfully complete all aspects of your job.

Although you report to the HR Director, you work independently and with no real direct supervision. The HR Director is available to you when you have questions using an open-door policy, but the only interaction you really have is informal hallway chat. The ability to work without tight supervision is one of the reasons you accepted this position.

Cell 1.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, your position is one of the many in your company that has shifted to a work from home schedule. The company has provided you with all the technology tools you need to work from home.

Looking back over the last several months, you can see that not much has really changed. Although the monthly employee seminars are now held via video conferencing, they continue to be well attended by employees.

The weekly newsletters have all been posted on time and you have been able to answer all employee questions via email, telephone calls, or personal video conference. The HR Director has even created a standing time for drop-in video office hours and has been very flexible in arranging meeting times with anyone who has questions, but you continue to enjoy your work without tight supervision.

Cell 2.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, your position is one of the many in your company that has shifted to a work from home schedule. The company has provided you with all the technology tools you need to work from home.

Looking back over the last several months, you can see that while some things have not really changed, in other ways this is not the same job you used to enjoy. Although the monthly employee seminars are now held via video conferencing, they continue to be well attended by employees.

The weekly newsletters have all been posted on time and you have been able to answer all employee questions via email, telephone calls, or personal video conference. However, the HR Director has created a standing time for mandatory video meetings, has instituted forms to be completed that outline the tasks you have completed each day, and has installed supervising software on your company issued laptop so that management can see in real time what you are working on.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Alegre I., Mas-Machuca M., Berbegal-Mirabent J. Antecedents of employee job satisfaction: Do they matter? Journal of Business Research. 2016;69(4):1390–1395. [Google Scholar]

- Akanji B., Mordi C., Ajonbadi H.A. The experiences of work-life balance, stress, and coping lifestyles of female professionals: Insights from a developing country. Employee Relations: The International Journal. 2020;42(4):999–1015. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkanasy N.M., Ayoko O.B., Jehn K.A. Understanding the physical environment of work and employee behavior: An affective events perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2014;35(8):1169–1184. doi: 10.1002/job.1973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bankins S. A process perspective on psychological contract change: Making sense of, and repairing, psychological contract breach and violation through employee coping actions. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2015;36(8):1071–1095. doi: 10.1002/job.2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beal D.J., Ghandour L. Stability, change, and the stability of change in daily workplace affect. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2011;32(4):526–546. doi: 10.1002/job.713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstrøm V.H., Svare H. Significance of monitoring and control for employees' felt trust, motivation, and mastery. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies. 2017;7(4):29–49. doi: 10.18291/njwls.v7i4.102356. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Braukmann J., Schmitt A., Ďuranová L., Ohly S. Identifying ICT-related affective events across life domains and examining their unique relationships with employee recovery. Journal of Business and Psychology. 2018;33(4):529–544. doi: 10.1007/s10869-017-9508-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell W.R., Olson-Buchanan J.B. The use of communication technologies after hours: The role of work attitudes and work-life conflict. Journal of Management. 2007;33(4):592–610. [Google Scholar]

- Bush J.T., Welsh D.T., Baer M.D., Waldman D. Discouraging unethicality versus encouraging ethicality: Unraveling the differential effects of prevention- and promotion-focused ethical leadership. Personnel Psychology. 2020 doi: 10.1111/peps.12386. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, And Programming, New York, Routledge.

- Byun G., Dai Y., Lee S., Kang S. Leader trust, competence, LMX, and member performance: A moderated mediation framework. Psychological Reports. 2017;120(6):1137–1159. doi: 10.1177/0033294117716465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carnevale J.B., Hatak I. Employee adjustment and well-being in the era of COVID-19: Implications for human resource management. Journal of Business Research. 2020;116:183–187. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi O.H., Saldamli A., Gursoy D. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on management-level hotel employees’ work behaviors: Moderating effects of working-from-home. International Journal of Hospitality Management. 2021;98:103020. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]