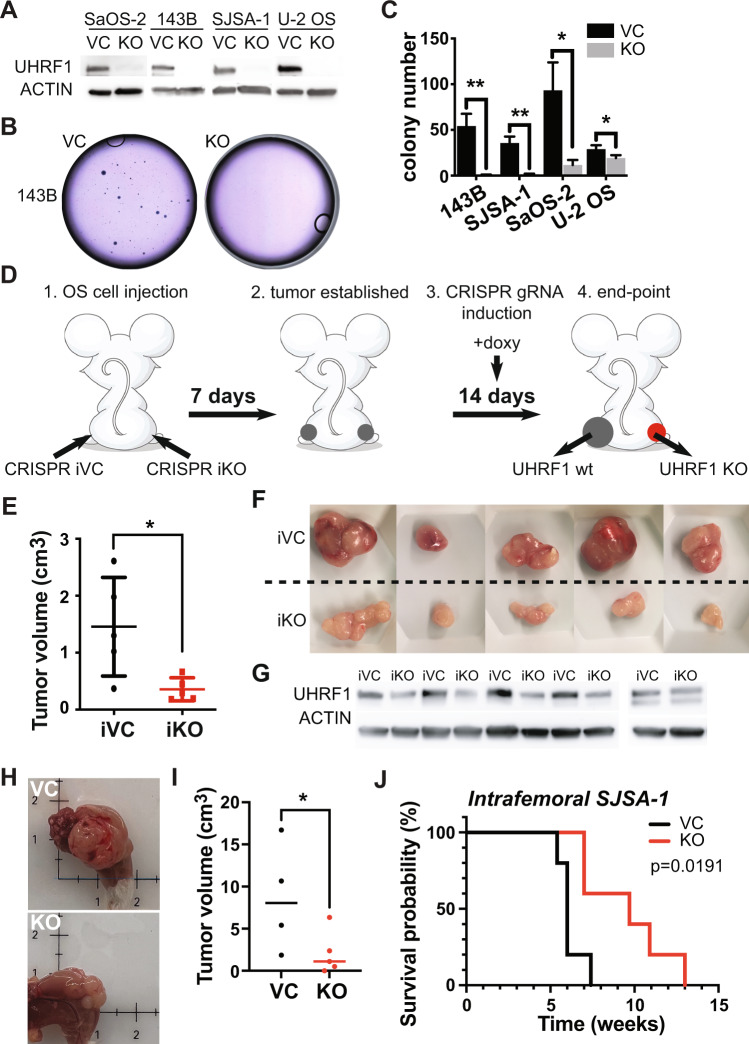

Fig. 2. UHRF1 promotes osteosarcoma tumor growth in vitro and in vivo.

A Western blot analysis of UHRF1 in CRISPR/Cas9-mediated UHRF1 knockout of osteosarcoma cell lines (KO) in comparison to non-targeting vector control (VC). β-actin was used as a loading control. B Representative images from clonogenic assay plates with 143B VC and UHRF1 KO. C Histogram of colony counts from clonogenic assay. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 by unpaired two-tailed t test. D Cartoon representation for doxycycline-inducible in vivo knockout for flank-injected osteosarcoma cell lines carrying a non-targeting sgRNA (iCRISPR VC) or UHRF1 sgRNA (iCRISPR KO). E Quantification of the tumor volume for each of the replicates. *P < 0.05 by paired two-tailed t test. F Images from tumors collected from subcutaneous injection of iCRISPR VC (iVC, n = 5) and iCRISPR KO (iKO, n = 5) SJSA-1. G Western blot verification of UHRF1 knockout in iKO compared to iVC for tumors shown in (F). β-actin was used as a loading control. H Representative images from tumors collected from intrafemoral injection of SJSA-1 VC and UHRF1 KO. I Quantification of the tumor volume for each of the replicates, 5 weeks after intrafemoral injection. A solid linerepresents median from n = 4 for VC and n = 5 for KO. *P < 0.05 by paired two-tailed t test. J Kaplan–Meier curves showing the survival of mice with orthotopic SJSA-1 VC (black, n = 5) and UHRF1 KO (red, n = 5) xenografts.