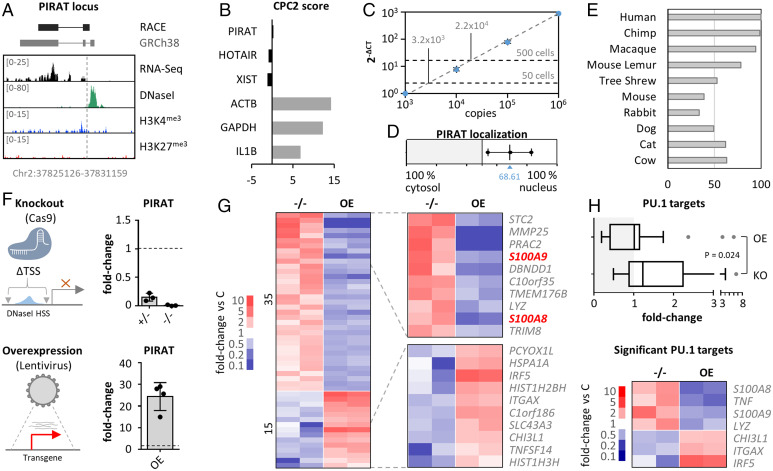

Fig. 4.

Role of PIRAT in human monocytes. (A) RACE-PCR refined (black) and annotated (gray) PIRAT splice structure and chromosomal position, compared to ENCODE primary CD14+-monocyte RNA-seq, DNaseI-seq, and ChIP-seq (H3K4me3 and H3K27me3) coverage. Track-height indicated in brackets. (B) CPC2 coding score of indicated lncRNAs and mRNAs. (C) PIRAT copy number enumeration by absolute qPCR, relative to PIRAT RNA standard. Two independent analysis (each three independent replicates), using RNA worth 50 and 500 CD14+ monocytes, respectively. Average PIRAT copy number (not yet divided by the number on input cells) is shown . (D) Subcellular localization of PIRAT in primary CD14+-monocytes (qRT-PCR, three independent experiments; C = cytoplasm, N = nucleus). (E) Conservation of RACE-PCR refined PIRAT sequence in the respective species (percentages). (F) Representation and qRT-PCR-validation of PIRAT mono- (+/−) and biallelic (−/−) knockout and lentiviral overexpression (OE) strategy (THP1 monocytes). (G) RNA-seq analysis of PIRAT knockout (−/−) and overexpression (OE) cells (color-coded mRNA fold-changes ≥ 2, compared to wild-type cells). (H, Upper) Base-mean fold-changes of PU.1 target genes in datasets from G. (Lower) PU.1-controled genes, significantly regulated (twofold or greater, P ≤ 0.05) into opposite directions after PIRAT knockout and overexpression, respectively. (H) Two-tailed Student’s t test.