Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To examine the frequency and severity of pain and use of pain therapies among long-term care residents with moderate to severe dementia and to explore the factors associated with increased pain severity.

DESIGN:

Prospective individual data were collected over 1 to 3 days for each participant.

SETTING:

Sixteen long-term care facilities in Alabama, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey.

PARTICIPANTS:

Residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment residing in a long-term care facility for at least 7 days were enrolled (N = 205). Residents were 47% female, predominantly white (69%), and 84 years old, on average (SD = 10 years).

MEASUREMENTS:

A comprehensive pain assessment protocol was used to evaluate pain severity and characteristics through medical record review, interviews with nursing home staff, physical examinations, as well as pain observation tools (Mobilization-Observation-Behavior-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale and Pain Intensity Measure for Persons With Dementia). Known correlates were also assessed (agitation, depression, and sleep).

RESULTS:

Experts’ pain evaluations indicated that residents’ usual pain was mild (mean = 1.6/10), and most experienced only intermittent pain (70%). However, 45% of residents experienced moderate to severe worst pain. Of residents, 90% received a pain therapy, with acetaminophen (87%) and opioids (32%) commonly utilized. Only 3% had a nondrug therapy documented in the medical record. The only resident characteristic that was significantly associated with pain severity was receipt of an opioid in the past week.

CONCLUSION:

Using a comprehensive pain assessment protocol, we found that most nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia had mild usual, intermittent pain and the vast majority received at least one pain therapy in the previous week. Although these findings reflect improvements in pain management compared with older studies, there is still room for improvement in that 45% of the sample experienced moderate to severe pain at some point in the previous week.

Keywords: dementia, long term carenursing homepain assessment, pain measurement

Untreated pain in older adults, including those with dementia and living in nursing homes, is associated with adverse consequences, which include decreased quality of life, diminished physical function, impaired sleep, depression, agitation, and aggressive behaviors.1–5 Inadequate assessment and treatment of pain may be more common in persons with dementia.6,7 Multiple studies show that, as cognitive impairment worsens, documented pain and likelihood of being prescribed analgesics decreases.6–8 Thus, persons with moderate to severe cognitive impairment are at greatest risk for poor outcomes.

For the past decade, numerous efforts have been made to improve pain assessment and management for nursing home residents and persons with dementia. The Advancing Excellence in America’s Nursing Homes initiative, which began in 2006, and its evolution to its current form, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS’) National Nursing Home Quality Improvement Campaign, have targeted pain in its extensive quality improvement activities (https://www.nhqualitycampaign.org/). Professional organizations have emphasized the importance of and provided guidance for assessing and managing pain in nursing home residents and/or persons with dementia.9–12 Studies document the challenges and barriers to improving practices related to the care of older persons with dementia in pain.13,14 Little is known about the impact of these earlier substantial efforts on improving pain in nursing home residents with dementia.

In their landmark pain management guideline published in 2002, the American Geriatrics Society estimated that “45% to 80% of [nursing home residents] have substantial pain that is undertreated” (p. S205). More recent studies suggest that the prevalence of persistent pain among nursing home residents has decreased over the past 10 to 12 years.7,15 However, it is not clear whether these decreases occurred across levels of cognitive impairment. Estimates of pain for residents with moderate to advanced dementia vary, depending on the measurement methods. Using the Minimum Data Set (MDS), version 3.0 (2011–2012 data), Hunnicutt et al reported that 70.5% of residents with moderate cognitive impairment and 49.5% of those with severe cognitive impairment had pain.15 Pain rates of 55% and 50.5% for moderately and severely impaired residents with cancer have been reported, again assessed using the MDS 3.0.6 Other studies show that roughly 44% to 47% of residents with significant cognitive impairment had pain when evaluated using observational pain tools.16,17 Approximately 39% of long-term nursing home residents with advanced dementia who were followed up for 18 months had nurse-reported pain.18

No gold standard has existed for identifying pain in dementia, and prior efforts emphasize MDS data, various behavior observation tools, provider estimations, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9), codes for pain-related diagnoses, with each approach leading to potentially different understandings of pain prevalence. Pain assessment for people with dementia requires a multidimensional approach, one that includes identifying painful diagnoses and conditions, eliciting self-report, when available, observation of pain-related behaviors, proxy reports, and use of an analgesic trial.19 Most descriptions of pain in persons with moderate to severe dementia use only one source or method for detecting pain. Even the MDS 3.0, with its enhanced pain measure (ie, section J), is problematic in that the assessment of pain for people with limited ability to communicate is excluded from publicly reported estimates of pain.20 Moreover, concerns about reporting high pain rates and deviation from CMS guidance for completing the MDS may result in underestimates of pain in people with more advanced cognitive impairment.

This article describes secondary analyses using data collected as part of a parent study to develop and test a pain observation tool for persons with dementia using items from existing measures.21,22 We employed a comprehensive pain evaluation conducted by an expert clinician as the “gold standard” pain measure. We also collected proxy pain reports from licensed staff nurses and certified nursing assistants, as well as observational pain measures that were completed by trained research staff. This allowed us to characterize the pain of nursing home residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment through a multifaceted lens. The purpose this article is to: (1) describe pain frequency, pattern, and severity and analgesic and nondrug treatment use in a sample of nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia; (2) compare expert clinicians’ pain ratings to those of licensed staff nurses and certified nursing assistants and research staff using observational pain tools; and (3) explore the factors associated with increased pain severity.

METHODS

Sample and Setting

Research participants were residents of 16 long-term care facilities located in Alabama, Georgia, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. Residents were eligible for the study if they had been at the long-term care facility for at least 7 days; had a diagnosis of dementia of any type (eg, Alzheimer disease or frontotemporal) and due to any cause (eg, Parkinson disease or traumatic brain injury) recorded in the medical record; were aged 50 years and older; and had moderately severe to severe cognitive impairment, as indicated by a score of less than 10 on the Brief Instrument of Mental Status (BIMS) evaluation.23,24 Initially, we included residents without regard to pain status because we wanted to develop and evaluate the pain observation tool among all levels of pain, including absence of pain. After enrolling 105 residents, we began a targeted recruitment effort of residents whom the nursing staff reported as having moderate to severe pain to balance the final sample across pain levels.

Written consent from the legally authorized representative, power of attorney, or next of kin was obtained for all participants. The Department of Veterans Affairs Central Institutional Review Board approved all study procedures.

Measures

Expert Clinician Pain Intensity Rating

The Expert Clinician Pain Intensity Rating (ECPIR) uses a standardized evaluation protocol that included five components (medical record review; targeted physical examination; interviews with available staff, family members, and primary care providers; resident interview, when possible; and observation of the resident during rest and activity). After completing these steps, an expert clinician completed a form that included assessment of current pain and usual, worst, and least pain, in the past week using a 1 to 10 Likert scale.25 Four experts, three experienced geriatric nurse practitioners and one doctorally prepared nurse, were trained in the protocol and made evaluations on all study participants.21,22

Nursing Home Staff Pain Ratings

We obtained surrogate pain intensity reports from certified nursing assistants who had cared for the resident at least three times in the previous week and licensed nurses who oversaw the care for the resident. Trained research coordinators identified these staff and solicited the staff member’s estimates of the resident’s “usual, worst, and least pain in the past week,” as well as current pain using a 0 (no pain) to 10 (pain as bad as it could be) scale.25

Mobilization-Observation-Behavior-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale

The Mobilization-Observation-Behavior-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale (MOBID) is a validated observational pain scale in which raters observe pain-related behaviors (pain noises, facial expressions, and defense movements) and rate pain intensity at rest and during a standardized protocol in which the patient is guided through five movements (opening both hands; stretching both arms toward head; stretching and bending both knees and hips; turning in bed to both sides; and guided to sit at the bedside).26–28 Following the guided activities, raters then assess the patient’s overall pain intensity using a 0 to 10 scale, with 0 indicating no pain and 10 indicating pain as bad as it possibly could be. The MOBID was completed by trained research coordinators.

Pain Intensity Measure for Persons With Dementia

The Pain Intensity Measure for Persons With Dementia (PIMD) is a seven-item, direct observational tool, in which the rater observes a person for 5 to 8 minutes during movement (eg, transferring, bathing, ambulating, and turning in bed) and scores each item on a 0 (behavior not observed) to 3 (severe) scale of intensity. Item scores are then summed to create a total PIMD score (possible range = 0–21), with higher scores indicating greater pain intensity. The PIMD has undergone initial psychometric testing and was found to be valid and reliable.21,22 In the parent study, the PIMD was completed up to six times by trained research coordinators, and the PIMD reported herein is the average of all PIMDs completed for a given participant during movement.

Other Variables/Covariates

In addition to pain measures, trained research staff collected demographic and clinical data from the resident’s chart. The expert clinician pain raters also extracted pain-related diagnoses, analgesic use, and nondrug therapies (eg, hot/cold treatments, massage, splinting, and physical therapy) from the medical record. We also measured residents’ depression, sleep disturbances, and agitation using validated tools: the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD),29 Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home (NPI-NH) Sleep Subscale,30,31 and Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (CMAI),32 respectively.

All study measures were administered by trained research coordinators from two study sites (Tuscaloosa Veterans Administration (VA) Medical Center, Tuscaloosa, AL; and Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VA Medical Center, Philadelphia, PA). These teams collected all data for each participant within 1 to 3 days. Data collection occurred between November 2013 and August 2016.

Analyses

To determine the prevalence and severity of pain, we limited our analysis to the first 105 participants. Because these participants did not have to meet the criterion of having nurse-reported pain, focusing on this group allowed us to characterize pain characteristics in a general long-term care sample of residents with dementia. To address aim 1, then, we calculated means and SDs, medians, and ranges of usual and worst pain in the previous week, as determined by the pain clinical experts. We also determined percentages of moderately and severely cognitively impaired residents with no pain, mild pain (ie, 1–4/10), moderate pain (ie, 5–6/10), and severe pain (ie, 7–10/10) using empirically derived cut points.33 Finally, using the entire sample, we compared the mean pain intensity scores for participants with moderate (BIMS score = 8–9; n = 31) and severe (BIMS score = ≤7; n = 162) cognitive impairment.

Using the entire sample, we then examined the percentage of participants receiving analgesics or nondrug pain therapies. We examined four categories of analgesic: acetaminophen, opioid, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug, and adjuvant pain medications (eg, topical analgesics, antidepressants, and antiseizure medications prescribed specifically for pain). Analgesic use was dichotomized as “yes” (ie, resident was prescribed scheduled medications and/or received one or more doses of “as-needed” analgesics in the previous 7 days) or “no” (ie, receiving no scheduled analgesics or “as-needed” doses of analgesics in the previous 7 days). We also determined if the resident had received any nonpharmacological therapy for pain (eg, hot/cold treatments, massage, splinting, or physical therapy) in the previous 7 days.

To examine factors associated with increasing pain severity, we constructed linear regression models with ECPIR worst and usual pain severity in the previous week as the dependent variables. Variables included in the model are participant demographic variables, number of pain-related diagnoses, CSDD, CMAI, NPI-NH Sleep scores, and receipt of pain treatments, clustered by facility.

RESULTS

Description of the Sample

The total sample included 205 participants, and the prevalence subsample consisted of 105 participants. The average age in the total sample was 84 years (SD = 10 years), 47% were female, and 69% were white; these participants had on average 2.5 (SD = 2.0) painful conditions. The most common painful condition was arthritis (47%). The prevalence subsample was similar to the total sample with two exceptions. First, there was a lower percentage of women (27%) because early recruitment efforts focused on Veterans Administration (VA) sites. In addition, participants in the prevalence subsample had, on average, 3.2 (SD = 2.2) painful conditions. Most of both samples were severely cognitively impaired (87%, prevalence sample; 81%, total sample). Table 1 summarizes the participant characteristics for the prevalence and total samples.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Prevalence Subsample | Total Sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Moderate (n = 13) | Severe (n = 91) | All (n = 105) | Moderate (n = 31) | Severe (n = 166) | All (n = 205) |

| Age, mean ± SD, y | 86 ± 9 | 83 ± 11 | 83 ± 11 | 84 ± 12 | 84 ± 10 | 84 ± 10 |

| Female sex | 3 (23) | 24 (27) | 27 (26) | 15 (48) | 73 (45) | 95 (47) |

| Education | ||||||

| High school or less | 5 (38) | 41 (45) | 47 (45) | 10 (32) | 73 (44) | 84 (41) |

| Postsecondary education | 3 (23) | 22 (24) | 25 (24) | 8 (26) | 42 (25) | 55 (27) |

| Missing | 5 (38) | 28 (31) | 33 (31) | 13 (42) | 51 (31) | 66 (32) |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 8 (62) | 58 (64) | 66 (63) | 21 (68) | 113 (68) | 141 (69) |

| Black or African American | 5 (38) | 31 (34) | 37 (35) | 10 (32) | 51 (31) | 62 (30) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) | 4 (2) |

| Non-Hispanic | 13 (100) | 87 (96) | 101 (96) | 31 (100) | 160 (96) | 199 (97) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Painful conditions | ||||||

| Arthritis | 8 (62) | 45 (54) | 53 (55) | 17 (55) | 71 (45) | 92 (47) |

| Upper GI paina | 5 (38) | 34 (41) | 39 (40) | 9 (29) | 64 (41) | 74 (38) |

| Miscellaneous painb | 7 (54) | 33 (40) | 41 (42) | 13 (42) | 60 (38) | 76 (39) |

| Constipation | 5 (38) | 32 (39) | 37 (38) | 13 (42) | 50 (32) | 64 (32) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 5 (38) | 17 (20) | 22 (23) | 10 (32) | 32 (20) | 42 (21) |

| Pressure ulcer or painful skin condition | 3 (23) | 30 (36) | 33 (34) | 5 (16) | 43 (27) | 48 (24) |

| Fracture, contracture, or osteomyelitis | 3 (23) | 27 (33) | 30 (31) | 4 (13) | 38 (24) | 42 (21) |

| Neuropathic painc | 3 (23) | 12 (14) | 15 (15) | 4 (13) | 14 (9) | 19 (10) |

| Cancer | 2 (15) | 15 (18) | 17 (18) | 3 (10) | 18 (11) | 21 (11) |

| Lower GI paind | 3 (23) | 15 (18) | 19 (20) | 5 (16) | 18 (11) | 24 (12) |

| Gout | 2 (15) | 4 (5) | 6 (6) | 2 (6) | 5 (3) | 8 (4) |

| Headache | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 0 (0) | 4 (3) | 4 (2) |

| Total painful conditions, mean ± SD | 3.7 ± 2.3 | 3.1 ± 2.2 | 3.2 ± 2.2 | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 2.5 ± 2.0 | 2.5 ± 2.0 |

| Cornell Scale of Depression in Dementia, mean ± SDe | 4.5 ± 4.6 | 4.6 ± 3.8 | 4.5 ± 3.9 | 3.9 ± 3.6 | 4.3 ± 4.2 | 4.3 ± 4.1 |

| Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, mean ± SDf | 41 ± 16 | 44 ± 15 | 43 ± 15 | 39 ± 12 | 44 ± 14 | 43 ± 14 |

| Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home Version Sleep subscale, mean ± SDg | 0.7 ± 2.3 | 0.1 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 1.0 | 0.3 ± 1.5 | 0.2 ± 0.7 | 0.2 ± 0.9 |

Note. Data are given as number (percentage) of each group, unless otherwise indicated.

Abbreviation: GI, gastrointestinal.

Peptic ulcer disease or gastroesophageal reflux.

Muscle spasms or diagnosis of chronic or generalized pain not otherwise accounted for.

Diabetic neuropathy, sciatica, phantom limb pain, post–herpetic neuralgia, or spinal cord compression.

Irritable bowel syndrome, hemorrhoids, or Crohn disease.

Possible range is 0 to 38.

Possible range is 29 to 203.

Possible range is 0 to 12.

Pain Characteristics

Table 2 outlines pain frequency, severity, and pattern, as evaluated by the expert clinicians, staff nurses and nursing assistants, and research staff (using observational pain measures). As determined by the expert clinicians, most pain experienced by the sample was intermittent (70%), and the mean “usual pain in the past week” was 1.6/10 (SD = 1.8). On average, “worst pain in the past week” was 4.3/10 (SD = 2.9). The expert clinicians assessed that 45% of the prevalence sample had moderate to severe worst pain, although only 7.8% of participants experienced moderate-severe usual pain.

Table 2.

Pain Frequency, Severity, and Pattern (N = 105)

| Severity, Mean (SD) | Pain Severity Levels, % | Pain Pattern, % | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | N | mean ± SD | No pain (0) | Mild | Moderate | Severe | No pain | Constant | Intermittent | Constant with exacerbations |

| Expert clinician | ||||||||||

| Worst past week (0–10) | 102 | 4.3 ± 2.9 | 12 | 42 | 21 | 25 | 21 | 2 | 70 | 7 |

| Usual past week (0–10) | 103 | 1.6 ± 1.8 | 39 | 53 | 6 | 2 | ||||

| Nursing home staff surrogate report, nurse | ||||||||||

| Worst pain (0–10) | 104 | 1.9 ± 3.0 | 62 | 17 | 7 | 13 | 59 | 0 | 38 | 4 |

| Usual pain (0–10) | 104 | 0.7 ± 1.5 | 73 | 22 | 4 | 1 | ||||

| Nursing home staff surrogate report, nursing assistant | ||||||||||

| Worst pain (0–10) | 104 | 2.7 ± 3.1 | 47 | 24 | 13 | 15 | 47 | 3 | 45 | 5 |

| Usual pain (0–10) | 104 | 1.3 ± 2.0 | 62 | 31 | 4 | 3 | ||||

| Observational pain measures | ||||||||||

| MOBID (possible range = 0–10) | 103 | 1.5 ± 1.7 | 43 | 50 | 6 | 1 | ||||

| PIMD (possible range = 0–21) | 88 | 2.7 ± 2.3 | ||||||||

Abbreviations: MOBID, Mobilization-Observation-Behavior-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale; PIMD, Pain Intensity Measure for Persons With Dementia.

Compared with expert clinicians, staff nurses’ and nursing assistants’ estimates of pain severity generally were lower, although nursing assistants’ ratings were closer to experts’ rating than those of licensed nurses. Staff also were more likely to report that residents had experienced “no pain” in the previous week than experts; similar to the expert clinicians, staff assessed that intermittent pain was more common than constant pain.

Pain severity, as assessed using observational pain tools while residents engaged in movement, was, on average, low. The mean pain score on the MOBID was 1.5/10 (SD = 1.7) and average PIMD scores were 2.7/21 (SD = 2.3).

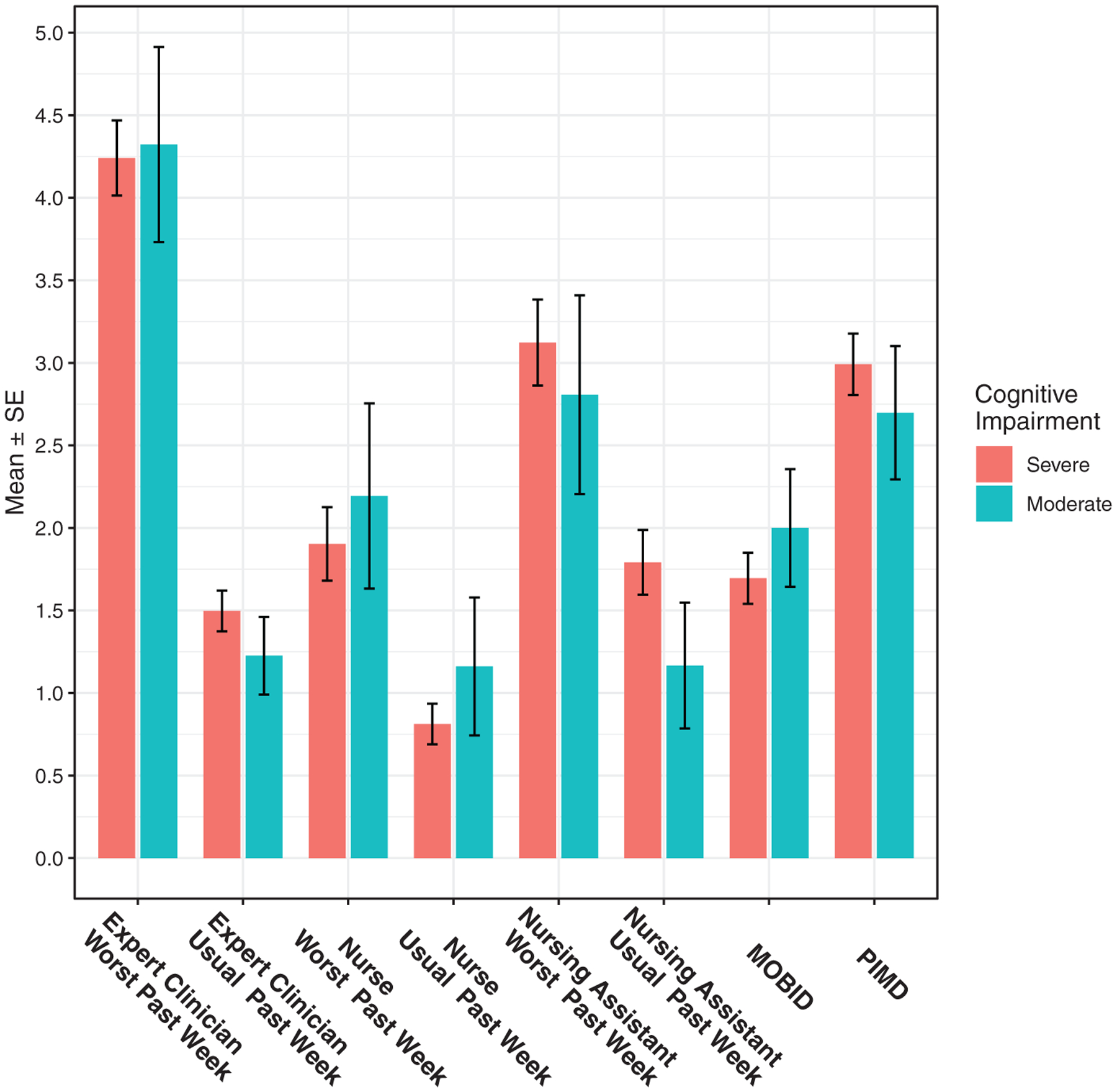

Figure 1 presents mean pain intensity for moderately and severely cognitively impaired participants, as measured using various assessment methods. Generally, differences between the groups were small, and none was statistically significant. Furthermore, there was no consistent pattern of differences between the two groups across the assessment methods.

Figure 1.

Mean pain intensity scores for participants with moderate (Brief Instrument of Mental Status [BIMS] score = 8–9) and severe (BIMS score = ≤7) cognitive impairment, across all assessment methods. MOBID indicates Mobilization-Observation-Behavior-Intensity-Dementia Pain Scale (possible range = 1–10); PIMD, Pain Intensity Measure for Persons With Dementia (possible range = 0–21).

Pain Therapies

Of the sample, 90% had received at least one pain therapy in the previous week (Table 3). Of the 21 participants who did not receive any pain treatment, only 3 had no pain recorded by the expert clinician. Of the 90% receiving pain therapies, the most common analgesic was acetaminophen (87%), and 32% of participants received an opioid in the last 7 days. Documentation of nondrug therapies was rare; only 3% received some type of nondrug treatment according to the medical record.

Table 3.

Pain Medications and Nondrug Therapies Received by Participants in the Previous Week (n = 205)

| Medication/Treatment | Severe Cognitive Impairment (N = 166) | Moderate Cognitive Impairment (N = 31) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | 137 (84) | 23 (74) | 167 (83) |

| Opioids | 52 (32) | 9 (29) | 65 (32) |

| NSAIDs | 12 (7) | 4 (13) | 16 (8) |

| Adjuvant | 26 (16) | 3 (10) | 32 (16) |

| Nondrug treatment | 5 (3) | 1 (3) | 6 (3) |

| No pain therapy | 15 (9) | 6 (19) | 21 (10)a |

Note. Data are given as number (percentage) of each group.

Abbreviation: NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

A total of 3 of 21 had no pain per pain expert; thus, 18 of 205, or 8.8%, of residents with pain had no pain therapy administered in the previous week.

Predictors of Pain Severity

Table 4 summarizes the results of the multivariate linear regression predicting expert-rated worst and usual pain in the past week. Only one participant-level variable was found to be significantly associated with pain severity: receipt of an opioid in the past week was positively associated with higher worst pain (β = 1.2; 95% confidence interval [CI] = .3–2.2; P = .013) and usual pain (β = 0.6; 95% CI = .1–1.1; P = .02). The analysis incorporated clustering by covariate adjustment for facility and reflected significant differences among sites. However, given the small number of observations at some facilities, coupled with other confounders (eg, different research staff at the study sites in Alabama and Pennsylvania; unmeasured differences in clinical practices), we were unable to examine this variation further.

Table 4.

Multivariate Linear Regression Predicting Expert-Rated Worst and Usual Pain in the Past Week

| Worst Pain (N = 180) | Usual Pain (N = 181) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Difference (95% CI) | P Value | Difference (95% CI) | P Value |

| Severely impaired (vs moderately) | −0.4 (−1.5 to 0.7) | .499 | −0.4 (−1.0 to 0.2) | .219 |

| Age, per 10 y | −0.1 (−0.5 to 0.4) | .743 | 0.0 (−0.2 to 0.3) | .712 |

| Female, vs male | −0.8 (−2.2 to 0.7) | .310 | −0.6 (−1.3 to 0.2) | .160 |

| Black or African American, vs white | 0.6 (−0.6 to 1.8) | .346 | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.8) | .640 |

| Hispanic/Latino vs non-Hispanic/non-Latino | 1.3 (−1.4 to 4.1) | .340 | 0.5 (−1.0 to 1.9) | .510 |

| Total No. of painful conditions, per 1 point | 0.2 (−0.1 to 0.5) | .226 | 0.1 (−0.0 to 0.3) | .105 |

| Cornell Scale of Depression in Dementia, per 5 points | 0.3 (−0.3 to 0.8) | .311 | −0.0 (−0.3 to 0.2) | .800 |

| Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory, per 10 points | 0.3 (−0.0 to 0.6) | .083 | 0.1 (−0.1 to 0.3) | .196 |

| NPI-NH, per 1 point | 0.1 (−0.3 to 0.6) | .654 | −0.0 (−0.2 to 0.2) | .955 |

| Acetaminophen, yes vs no | −0.5 (−1.5 to 0.6) | .372 | −0.3 (−0.8 to 0.3) | .360 |

| Opioids, yes vs no | 1.2 (0.3 to 2.2) | .013 | 0.6 (0.1 to 1.1) | .020 |

| NSAIDs, yes vs no | 0.3 (−1.4 to 2.0) | .715 | 0.0 (−0.9 to 0.9) | .929 |

| Adjuvant, yes vs no | 0.9 (−0.4 to 2.1) | .180 | 0.4 (−0.2 to 1.1) | .203 |

| Nondrug treatment, yes vs no | 0.6 (−3.5 to 4.7) | .768 | 1.2 (−1.0 to 3.3) | .278 |

Note. Covariate adjustment for site was included in the models but (to save space) is not shown in the table (tests for study effect: P < .001 for worst pain and P = .226 for usual pain). Statistically significant effects are boldfaced.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; NPI-NH, Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.

DISCUSSION

This study sought to characterize the pain experiences of nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia using a comprehensive pain assessment protocol. Our findings indicate that experts judged most residents as having intermittent pain that was usually mild. Similarly, we found low average pain intensity using direct observational pain tools that were completed during movement. These findings may reflect good pain management; we documented that 90% of residents received at least one pain therapy in the previous week, with more of those who were severely cognitively impaired receiving treatment (91%) than those who were moderately (81%) impaired. Despite these encouraging findings, 45% of residents experienced moderate to severe worst pain at some time in the week prior to our evaluation.

In our prevalence sample, 79% of moderately to severely cognitively impaired residents were found to have pain in the previous week. These rates are somewhat higher than those reported by Hunnicutt et al.15 Our higher rates may be attributable to the differences in pain measurement methods. Hunnicutt et al15 derived their pain prevalence from MDS 3.0 data. Although the MDS 3.0 is believed to be a better measure of pain overall than previous versions of this instrument, Wei and colleagues found poor agreement on MDS pain measurements and more frequent staff assessments of pain.34 Moreover, our expert clinicians performed a comprehensive pain evaluation that maximized the likelihood of identifying pain presence and severity. While this method may be superior in capturing the pain experience, it is unlikely that nursing home staff and providers are able to perform such lengthy evaluations on a regular basis. Therefore, more parsimonious, but equally sensitive, methods to assess pain are needed.

In contrast to earlier studies that found significant negative associations between pain and increased cognitive impairment, we found small, inconsistent, and statistically nonsignificant differences in pain severity between participants with moderate or severe cognitive impairment across several assessment methods.6,8 This disparate finding could reflect differences in the samples; our study included only participants with moderate to severe impairment, whereas the other studies’ samples encompassed the full range of cognitive function, from fully intact to severe impairment. Another possible explanation is that both groups had a similar likelihood of being prescribed analgesics, thereby eliminating differences in pain levels.

Our study also suggests that nursing home staff may underestimate pain in residents with dementia, a finding that has been reported in other studies.35,36 Our expert pain clinicians were more likely to identify pain and to rate that pain as more severe than either licensed nurses or nursing assistants. Studies of interventions to enhance pain assessment and management in nursing homes have frequently been of low quality37 or have not been successful in promoting significant or lasting improvements in clinical practice.13,38 Future studies designed to improve pain assessment and management should incorporate evidence-based implementation science principles to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of these interventions.13

In addition to expert ratings, we used two observational validated tools, the MOBID and the PIMD, to measure pain.21,22,28 For both tools, raters observe pain-related behaviors during movement, which generally leads to higher scores than when observations occur during rest.22,39

The tools differ in that the PIMD has raters judge the intensity of pain-related behaviors and sums the score on all items. In contrast, raters completing the MOBID mark the presence or absence of selected pain-related behaviors during a movement protocol and then rate the overall estimated pain severity using a 0 to 10 scale.26,27 While the mean pain severity estimates for both tools were relatively similar to those of experts’ usual pain estimates, they were lower than experts’ worst pain estimates. Other investigators have identified significant differences in pain ratings among different measurement methods,40 which is to be expected. However, our findings suggest that direct observational tools should be augmented with a comprehensive, interdisciplinary assessment of pain.

We found that less than 9% of the sample was identified to be in pain and not receiving pain medication. These data contrast with much earlier studies that documented high rates of undertreated pain in nursing home residents with dementia. For example, using MDS data from 2001 to 2004, Reynolds et al8 reported that, among nursing home residents with pain, 36.4% of those with moderate and 43.8% with severe cognitive impairment had no prescribed analgesics. Fain et al examined 2007 to 2008 data and identified no analgesia rates of 20% and 25.6% among residents with persistent pain and moderate to severe cognitive impairment, respectively.7 Our estimate of untreated pain is more aligned with those of the recent study of Hunnicutt et al, showing that only 6.9% of residents with moderate and 8.5% of those with severe cognitive impairment and pain received no analgesics.15 Taken together, these previous studies and our current findings strongly indicate that pain treatment for nursing home residents with dementia has improved considerably over the last two decades.

With federal and regulatory emphases on using nondrug interventions as part of the treatment plan for chronic pain, our finding that only 3% of residents had a documented nondrug pain therapy in the medical record is a concern. This low rate may reflect inadequate documentation or an actual dearth of nondrug therapies to manage pain in this population. Other studies have identified that nondrug pain therapies are underutilized in nursing homes and among older adults with dementia.8,41–43 There are several possible explanations for a low rate of use. First, certain nondrug therapies, such as mindfulness or cognitive-behavioral therapy, may be inappropriate for persons with moderate to severe cognitive impairment; furthermore, strong empirical evidence for the effectiveness of nondrug pain treatments in this group is lacking. Despite these problems, judicious use of nondrug approaches is widely accepted and there are options with limited risk and potential benefit, such as heat and cold application, physical therapies, or massage.44 Other likely explanations are that nursing home staff and providers lack sufficient training in providing nondrug pain therapies or simply do not prioritize their use.43,45–47 Other barriers are perceptions that nonpharmacologic pain treatments are ineffective or too time-consuming to implement.45,48 Future research to address these challenges is warranted.

In examining the associations among patient characteristics and pain severity, we found only one significant predictor of pain severity, receipt of an opioid in the previous week. This finding contrasts with earlier studies showing significant associations between pain and agitation, depression, and sleep disturbance.1–5 Our relatively small sample size may have precluded certain associations from reaching statistical significance. The significant association between pain severity and receipt of an opioid is not surprising, since opioids have been recommended for moderate to severe pain.10 However, our findings do call into question the adequacy of pharmacologic treatment of moderate to severe pain in the sample.

This study was not without limitations. Despite recruitment across 16 diverse long-term care facilities in two geographic regions of the United States, our sample was relatively small and included more men than is typical in national samples. Although nearly 70% of the sample was white non-Hispanic, this percentage is similar to national estimates of nursing home residents.49 We determined pain prevalence and characteristics using a rigorous, multidimensional evaluation protocol that was completed by expert geriatric pain clinicians; however, these clinicians did not provide ongoing care to the residents enrolled in the study and, thus, may have underestimated pain frequency and severity. Moreover, we did not conduct longitudinal pain evaluations and, thus, characterizations of changes over time may not be accurate. Nonetheless, experts identified higher rates of pain and pain severity than did nursing home staff, suggesting that staff may be underidentifying pain, a finding that is consistent with previous studies.35 Finally, use of nondrug therapies was determined only through the medical record and, as a result, may be an underestimate.

In conclusion, this study contributes to the empirical literature by characterizing pain severity, prevalence, and treatment among nursing home residents with moderate to severe dementia. Our findings corroborate those of recent studies,50 indicating that although pain is common among nursing home residents with dementia, it typically is mild and intermittent. Moreover, pharmacologic treatment of pain among nursing home residents with dementia appears to have improved over the last few decades. Nonetheless, a small but important group of residents with pain received no pain treatments in the previous week. Furthermore, nearly half of the sample had an episode of moderate to severe pain, suggesting that pain management for substantial numbers of residents with dementia is inadequate.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial Disclosure:

Supported by a grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Health Services Research and Development Service (1I01HX000507).

Sponsor’s Role:

The study sponsor had no role in the design, execution, or reporting of the research. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the US government.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: No conflicts, except for those who are employed at the Department of Veterans Affairs: Mary Ersek, Princess V. Nash, Michelle M. Hilgeman, Amber Collins, and Phoebe Block.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahn H, Horgas A. The relationship between pain and disruptive behaviors in nursing home residents with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2013;13:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flo E, Gulla C, Husebo BS. Effective pain management in patients with dementia: benefits beyond pain? Drugs Aging. 2014;31(12):863–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corbett A, Husebo B, Malcangio M, et al. Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol. 2012;8(5):264–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Erdal A, Flo E, Selbaek G, et al. Associations between pain and depression in nursing home patients at different stages of dementia. J Affect Disord. 2017; 218:8–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flo E, Bjorvatn B, Corbett A, Pallesen S, Husebo BS. Joint occurrence of pain and sleep disturbances in people with dementia: a systematic review. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14(5):538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dube CE, Mack DS, Hunnicutt JN, Lapane KL. Cognitive impairment and pain among nursing home residents with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(6):1509–1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fain KM, Alexander GC, Dore DD, Segal JB, Zullo AR, Castillo-Salgado C. Frequency and predictors of analgesic prescribing in U.S. nursing home residents with persistent pain. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(2):286–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reynolds KS, Hanson LC, DeVellis RF, Henderson M, Steinhauser KE. Disparities in pain management between cognitively intact and cognitively impaired nursing home residents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35(4): 388–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.AGS Panel on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(suppl 6):S205–S224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Geriatrics Society Panel on Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons. Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1331–1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Medical Directors Association pain management in the long term care setting. 2012. Columbia, MD: American Medical Directors Association. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Herr K, Coyne PJ, McCaffery M, Manworren R, Merkel S. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: position statement with clinical practice recommendations. Pain Manag Nurs. 2011;12(4):230–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ersek M, Neradilek MB, Herr K, Jablonski A, Polissar N, Du Pen A. Pain management algorithms for implementing best practices in nursing homes: results of a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(4): 348–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaasalainen S, Brazil K, Akhtar-Danesh N, et al. The evaluation of an interdisciplinary pain protocol in long term care. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13 (7):664.e1–664.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunnicutt JN, Ulbricht CM, Tjia J, Lapane KL. Pain and pharmacologic pain management in long-stay nursing home residents. Pain. 2017;158(6): 1091–1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwakhalen SM, Koopmans RT, Geels PJ, Berger MP, Hamers JP. The prevalence of pain in nursing home residents with dementia measured using an observational pain scale. Eur J Pain. 2009;13(1):89–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leong IY, Nuo TH. Prevalence of pain in nursing home residents with different cognitive and communicative abilities. Clin J Pain. 2007;23(2):119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1529–1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herr K, Coyne P, Ely E, Gélinas C, Manworren R. Pain assessment in the patient unable to self-report: clinical practice recommendations in support of the ASPMN 2019 position statement. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019;20(5): 404–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saliba D, Jones M, Streim J, Ouslander J, Berlowitz D, Buchanan J. Overview of significant changes in the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes version 3.0. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ersek M, Herr K, Hilgeman MM, et al. Developing a pain intensity measure for persons with dementia: initial construction and testing. Pain Med. 2019; 20(6):1078–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ersek M, Neradilek MB, Herr K, et al. Psychometric evaluation of a pain intensity measure for persons with dementia. Pain Med. 2019;20(6):1093–1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chodosh J, Edelen MO, Buchanan JL, et al. Nursing home assessment of cognitive impairment: development and testing of a brief instrument of mental status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(11):2069–2075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saliba D, Buchanan J, Edelen MO, et al. MDS 3.0: Brief Interview for Mental Status. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2012;13(7):611–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23(2):129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Husebo BS, Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Husebo SB, Ljunggren AE. Pain in older persons with severe dementia: psychometric properties of the Mobilization-Observation-Behaviour-Intensity-Dementia (MOBID-2) Pain Scale in a clinical setting. Scand J Caring Sci. 2010;24(2):380–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Husebo BS, Ostelo R, Strand LI. The MOBID-2 pain scale: reliability and responsiveness to pain in patients with dementia. Eur J Pain. 2014;18(10): 1419–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herr K, Sefcik JS, Neradilek MB, Hilgeman MM, Nash P, Ersek M. Psychometric evaluation of the MOBID dementia pain scale in U.S. nursing homes. Pain Manag Nurs. 2019;30(3):253–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, Shamoian CA. Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1988;23(3):271–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–2314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lange RT, Hopp GA, Kang N. Psychometric properties and factor structure of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Nursing Home version in an elderly neuropsychiatric population. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(5):440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen-Mansfield J Conceptualization of agitation: results based on the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory and the Agitation Behavior Mapping Instrument. Int Psychogeriatr. 1996;8(suppl 3)):309–315. discussion 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cleeland CS, Nakamura Y, Mendoza TR, Edwards KR, Douglas J, Serlin RC. Dimensions of the impact of cancer pain in a four country sample: new information from multidimensional scaling. Pain. 1996;67(2–3): 267–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei YJ, Solberg L, Chen C, et al. Pain assessments in MDS 3.0: agreement with vital sign pain records of nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:2421–2422. 10.1111/jgs.16122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ersek M, Polissar N, Neradilek MB. Development of a composite pain measure for persons with advanced dementia: exploratory analyses in self-reporting nursing home residents. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(3): 566–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ngu SS, Tan MP, Subramanian P, et al. Pain assessment using self-reported, nurse-reported, and observational pain assessment tools among older individuals with cognitive impairment. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(4):595–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Herman AD, Johnson TM 2nd, Ritchie CS, Parmelee PA. Pain management interventions in the nursing home: a structured review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(7):1258–1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mamhidir AG, Sjolund BM, Flackman B, Wimo A, Skoldunger A, Engstrom M. Systematic pain assessment in nursing homes: a cluster-randomized trial using mixed-methods approach. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17 (1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Herr K, Bursch H, Ersek M, Miller LL, Swafford K. Use of pain-behavioral assessment tools in the nursing home: expert consensus recommendations for practice. J Geronto Nurs. 2010;36(3):18–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen-Mansfield J The relationship between different pain assessments in dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(1):86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jablonski A, Ersek M. Nursing home staff adherence to evidence-based pain management practices. J Gerontol Nurs. 2009;35(7):28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lukas A, Mayer B, Fialova D, et al. Treatment of pain in European nursing homes: results from the Services and Health for Elderly in Long TERm Care (SHELTER) study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(11):821–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalinowski S, Budnick A, Kuhnert R, et al. Nonpharmacologic pain management interventions in German nursing homes: a cluster randomized trial. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16(4):464–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corbett A, Nunez KM, Smeaton E, et al. The landscape of pain management in people with dementia living in care homes: a mixed methods study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;31(12):1354–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chandler RC, Zwakhalen SMG, Docking R, Bruneau B, Schofield P. Attitudinal & knowledge barriers towards effective pain assessment & management in dementia: a narrative synthesis. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2017;14(5): 523–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Veal F, Williams M, Bereznicki L, et al. Barriers to optimal pain management in aged care facilities: an Australian qualitative study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2018;19(2):177–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zwakhalen SM, Hamers JP, Peijnenburg RH, Berger MP. Nursing staff knowledge and beliefs about pain in elderly nursing home residents with dementia. Pain Res Manag. 2007;12(3):177–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barry HE, Parsons C, Passmore AP, Hughes CM. Community pharmacists and people with dementia: a cross-sectional survey exploring experiences, attitudes, and knowledge of pain and its management. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;28(10):1077–1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nursing Home Data Compendium 2015. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (online). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/Downloads/nursinghomedatacompendium_508-2015.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2019.

- 50.Hunnicutt JN, Tjia J, Lapane KL. Hospice use and pain management in elderly nursing home residents with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017; 53(3):561–570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]