Abstract

Infectious diseases have remained one of humanity’s biggest problems for decades. Multiple disease infections, in particular, have been shown to increase the difficulty of diagnosing and treating infected people, resulting in worsening human health. For example, the presence of influenza in the population is exacerbating the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. We formulate and analyze a deterministic mathematical model that incorporates the biological dynamics of COVID-19 and influenza to effectively investigate the co-dynamics of the two diseases in the public. The existence and stability of the disease-free equilibrium of COVID-19-only and influenza-only sub-models are established by using their respective threshold quantities. The result shows that the COVID-19 free equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable when , whereas the influenza-only model, is locally asymptotically stable when . Furthermore, the existence of the endemic equilibria of the sub-models is examined while the conditions for the phenomenon of backward bifurcation are presented. A generalized analytical result of the COVID-19-influenza co-infection model is presented. We run a numerical simulation on the model without optimal control to see how competitive outcomes between-hosts and within-hosts affect disease co-dynamics. The findings established that disease competitive dynamics in the population are determined by transmission probabilities and threshold quantities. To obtain the optimal control problem, we extend the formulated model by including three time-dependent control functions. The maximum principle of Pontryagin was used to prove the existence of the optimal control problem and to derive the necessary conditions for optimum disease control. A numerical simulation was performed to demonstrate the impact of different combinations of control strategies on the infected population. The findings show that, while single and twofold control interventions can be used to reduce disease, the threefold control intervention, which incorporates all three controls, will be the most effective in reducing COVID-19 and influenza in the population.

Keywords: COVID-19, Influenza, Co-infection, Optimal control, Reproduction number

1. Introduction

Near the end of 2019, the new severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) also known as COVID-19 was discovered in Wuhan, China. It did not take long for the new disease to spread across nearly the entire globe [1]. According to Johns Hopkins University and Medicine, this ongoing pandemic has resulted in the deaths of approximately 6 million people around the world as of the time of writing this article. The common symptoms of this deadly disease include fever, cough, headache, fatigue, difficulty breathing, loss of smell, and loss of taste. Individuals infected with the virus may experience mild to severe symptoms 1–14 days after exposure [2]. The virus is known to spread quickly from person to person and from contaminated surfaces when a droplet of the virus encounters a human. Prior to the introduction of vaccines, the government and decision-makers encouraged the public to focus on non-pharmaceutical interventions. These non-pharmaceutical interventions include personal hygiene and cough etiquette, social distancing, school closures, quarantine rate, teleworking, hospitalization of positive cases and travel restrictions, contact tracing of suspected individuals into quarantine, and wearing of face masks [1], [3]. In addition, to control the disease epidemic the number of cases was also reduced by using intensive medical care, airports diagnosis and surveillance, rapid vaccination, and screening of exposed individuals [4], [5]. Despite the existence of infection control and prevention measures, different variants of the disease continued to emerge in various countries around the world. It started with alpha, then beta, delta, and now the ongoing omicron variant [6], [7], [8], which dramatically increases the number of infected people while also increasing the mortality rate. This is because they have the potential to increase transmission and reduce the effectiveness of vaccines against them.

Influenza, also known as the flu, is another infectious disease that has long been a public health concern. Seasonal influenza outbreaks affect millions of people each year, claiming the lives of about 500,000 people [9]. Although there is mounting evidence that aerosols play a significant role in influenza transmission, it has been demonstrated that influenza dynamics and control are transmitted solely through direct contact and large droplets, necessitating proximity [10]. Influenza symptoms appear one to four days after exposure to the virus and last for two to eight days. Fever, coughing, chills, headaches, muscle pain or arching, loss of appetite, fatigue, sore throat, and discomfort are common symptoms. All these symptoms are very similar to those of COVID-19, making diagnosis and treatment difficult. COVID-19, a deadly disease, became a pandemic as a result of misunderstandings about its symptoms and the time of year (winter) when influenza is most common. The use of a vaccine, case isolation, therapeutic and prophylactic antiviral treatment, air traffic reduction, global influenza pandemic vaccination program or quarantine policy, and ventilation are some of the control strategies used in mitigating the spread of influenza [11], [12], [13]. COVID-19 is of severe magnitude due to the seasonality of influenza disease, which is determined by several factors, including the vaccine’s effectiveness and the characteristics of the circulating virus. Supportive treatment, it was discovered, is still the mainstay of treatment for these co-infections [14]. Because the clinical presentation, transmission mechanism, characteristics, and symptoms of influenza A and COVID-19 [15] are so similar, diagnosing and initiating proper treatment for the two conditions is extremely difficult. A study was conducted to determine the rate of co-infection and its impact on clinical course and outcome [16].

Since the first appearance of the new coronavirus disease and its variants in Wuhan, several mathematical models have been developed to better understand transmission dynamics and various control strategies. Some of these studies includes [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23] and the references therein. For example, studies have looked into the effects of non-pharmaceutical strategies such as wearing a nose mask, hand-washing, social distancing, and isolation on COVID-19 control. Similarly, mathematical models have been developed and analyzed to study the dynamics of influenza spread and control using various approaches (see [24], [25], [26], [27], [28] and the references therein). Many researchers have used the optimal control theory to study the impact of different control measures on mitigating disease burden (see [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34], [35] and the references therein). To better understand the co-dynamics of COVID-19 and influenza in the presence of some control measures, we present a deterministic model to investigate the impact of within-host and between-host competitive outcomes on the dynamics of the diseases. To the best of our knowledge, one of the novelties of this work is that it is the first study to investigate the impact of within-host and between-host competitive outcomes on the co-dynamics of COVID-19 and influenza co-infection. This will enable us to comprehend the influence of the co-infection mechanism on the spread of disease in the human population. The rest of the paper is laid out as follows. Section 2 presents the formulated model, descriptions, and assumptions. A detailed theoretical analysis of the model is presented in Section 3. This includes the analysis of the COVID-19-only, influenza-only, and co-infection sub-models. Section 4 contains a detailed formulation of the optimal control of the full model as well as its analyses. In Sections 5.1, 5.2, numerical simulations and discussions of the non-optimal control model and the model with optimal control are presented, respectively. Section 6 contains the conclusion and useful recommendations for health policymakers.

2. Model formulation

The changed trajectory of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic remains a challenge to the healthcare system and humanity. Since December 2019 when the first outbreak of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) popularly known as COVID-19 initially appeared in Wuhan, China [2], many researchers have extensively studied the dynamics and control of this disease in an attempt to curtail its spread all over the world. Sadly, there have been reports of the mutation of this virus, thus leading to more complications in controlling the occurrence of infection cases. For instance, the newly omicron variant characterized with mild symptoms has shown to be highly transmissible among both vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals [36], [37]. Among other challenges faced by the healthcare system in combating the threat of COVID-19 is the existence of some other infectious diseases sharing similar symptoms of infection, thus leading to more complications in diagnosing infected individuals. This among many other diseases includes influenza, known as flu [38], [39]. The complexity of the current pandemic will be exacerbated by the presence of multiple diseases co-infection, as studies have shown that multiple infections of diseases have a higher chance of worsening human health than a single infection [40], [41]. Following the reports from several studies about the possibilities of the co-infection of COVID-19 and influenza [14], [42], [43], [44], we develop a more generalized scenario of a co-infection deterministic mathematical model, to investigate the co-dynamics of COVID-19 and influenza in a population. The fifteen compartmental model with the total population at time , represented by , is stratified into mutually-exclusively population of susceptible individuals , vaccinated individuals against COVID-19, influenza, and both disease ( respectively), exposed individuals to COVID-19, influenza, and both disease ( respectively), COVID-19 asymptomatic infectious, symptomatic infectious, and hospitalized infectious individuals ( respectively), influenza infectious individuals , co-infected infectious individuals , recovered individuals from COVID-19, influenza, and both disease ( respectively). To simplify the notations, we will subsequently remove the time in the model variables such that the total human population is given as

| (1) |

We emphasize that the individuals in the exposed compartment are the newly infected people with the respective disease, but are not able to transfer the disease (i.e. people who are not yet infectious), while the asymptomatic infectious, symptomatic infectious, and hospitalized infectious individuals are infectious individuals that are capable of transmitting the disease. The co-infection model used in studying the co-dynamic of COVID-19 and influenza is given by the following deterministic system of nonlinear differential equations

| (2) |

with the initial conditions

| (3) |

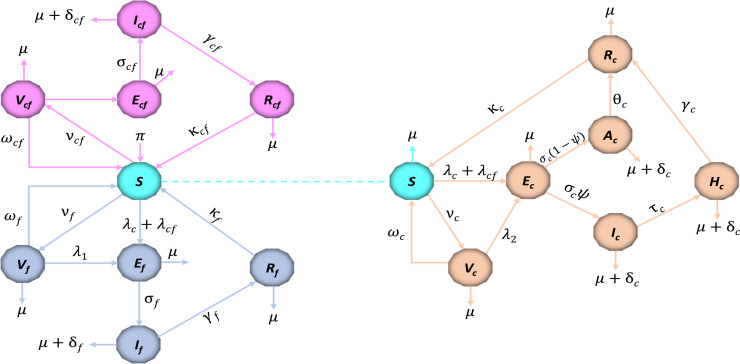

The description of the model variables and parameters are provided in Table 1, Table 2 respectively, while the flow diagram is depicted in Fig. 1. In model (2), the vaccination rate is given as , and the force of infection , where the respective forces of infection , , , and are given below as

| (4) |

In model (2), the susceptible individuals become infected with COVID-19 virus after an effective contact with an individual in the , , and classes, at the rate . The possibility of been infected by a hospitalized individual is incorporated in the force of infection, since these are infectious people who are admitted to healthcare facilities or individual homes due to virus infection (see [29], [31], [33], [35]). The infection modification parameter and rationalizes the assumed increase in the comparative infectiousness of the symptomatic infectious individuals over the asymptomatic and hospitalized infectious individuals. In addition, the susceptible individuals become infected with influenza or co-infection of the two disease, following an effective contacts with an influenza infectious individual , or an infectious co-infected individual , at the rate and respectively. The parameter , , , and represents the effective contact rate leading to COVID-19, influenza transmission, and co-infection transmission respectively. Susceptible individuals are required to be vaccinated against the two disease, since there is no universal vaccine for COVID-19 and influenza (i.e. vaccination against one disease do not provide immunity against the other). Thus, the vaccination rate against COVID-19 and influenza is given as , and respectively, while represent the rate at which individuals are vaccinated against the two disease. Since the vaccines against COVID-19 and influenza are imperfect [45], [46], the vaccinated individual populations , , are reduced by the respective force of infection at a reduced rate of , , and respectively, with a protective vaccine efficacy satisfying , , and .

Table 1.

Description of the model variables.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Population of susceptible individuals | |

| Population of individuals vaccinated against COVID-19 | |

| Population of individuals vaccinated against influenza | |

| Population of individuals vaccinated against COVID-19 and influenza | |

| Population of individuals exposed to COVID-19 only | |

| Population of individuals exposed to influenza only | |

| Population of individuals exposed to COVID-19 and influenza | |

| Population of COVID-19 asymptomatic infectious individuals | |

| Population of COVID-19 symptomatic infectious individuals | |

| Population of infectious individuals hospitalized for corona virus | |

| Population of influenza infectious individuals | |

| Population of COVID-19 and influenza infectious individuals | |

| Population of individuals recovered from COVID-19 | |

| Population of individuals recovered from influenza | |

| Population of individuals recovered from both COVID-19 and influenza |

Table 2.

The description of parameters and values.

| Parameter | Description | Value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment rate of susceptible individuals | [47] | ||

| Infection modification parameter for the asymptomatic infection rate | 0.45 | [48] | |

| Infection modification parameter for the hospitalized infection rate | 0.4509 | [48] | |

| Transmission rate of COVID-19 | 0.5249 | [47] | |

| Transmission rate of influenza | 0.203 | [49] | |

| Vaccination rate against COVID-19 | 0.0203 | [45] | |

| Vaccination rate against influenza | 0.00027375 | [50] | |

| Vaccination rate against COVID-19 and influenza | 0.00027375–0.0203 | Assumed | |

| Immunity waning rate of recovered individuals with COVID-19 | 0.011 | [31] | |

| Immunity waning rate of recovered individuals with influenza | 0.088 | [51] | |

| Immunity waning rate of recovered individuals with co-infection | 0.011–0.088 | Assumed | |

| Vaccine waning rate of COVID-19 | 0.000297 | [47] | |

| Vaccine waning rate of influenza | 0.15 | [51] | |

| Vaccine waning rate of COVID-19 and influenza | 0.000297–0.15 | Assumed | |

| COVID-19 vaccine efficacy | 0.70 | [47] | |

| Influenza vaccine efficacy | 0.77 | [50] | |

| COVID-19 and influenza vaccine efficacy | 0.80 | Assumed | |

| COVID-19 progression rate from the exposed to either | 0.40 | [47] | |

| asymptomatic or symptomatic infectious | |||

| Influenza progression rate from the exposed to infectious | 0.40 | [52] | |

| co-infection progression rate from the exposed to infectious | 0.40 | Assumed | |

| Fraction of COVID-19 exposed individuals becoming symptomatic | 0.60 | [53] | |

| Natural mortality rate | 0.0003516 | [47] | |

| Death due to COVID-19 | 0.008 | [54] | |

| Death due to influenza | 0.021 | [50] | |

| Death due to co-infection | 0.021–0.026 | Assumed | |

| Hospitalization rate of symptomatic infectious individuals | 0.0624 | [33] | |

| Recovery rate of COVID-19 asymptomatic infectious individuals | 0.13978 | [33] | |

| Recovery rate of COVID-19 hospitalized infectious individuals | 0.125 | [47] | |

| Recovery rate of influenza infectious individuals | 0.1998 | [50] | |

| Recovery rate of co-infected infectious individuals | 0.125–0.1998 | Assumed | |

| Reduction of susceptibility to COVID-19 infection | 0.50 | Assumed | |

| Reduction of susceptibility to influenza infection | 0.50 | Assumed |

Fig. 1.

The schematic diagram of the co-infection model (2). The dotted line represents an extension of susceptible individuals, and the forces of infection , and for depiction convenience.

Some of the main assumptions made in the formulation of the co-infection model (2) are stated below.

-

1.

To date, since there is no justification about the disease infection that will be transferred to a person after effective contact with an infectious co-infected individual, we assume super-infection dynamics which is a result of the competitive outcomes at the within-host level. This implies that an infectious co-infected individual will transmit the infection that has the within-host competitive advantage. This could be a result of the viral load level or the transmission probability rate of the disease. Thus, is the force of infection that indicates when COVID-19 has the within-host advantage over influenza, while is the force of infection that indicates when influenza has the within-host advantage over COVID-19. The parameter indicates that COVID-19 is transmitted in infectious co-infected individuals, while indicates that influenza is transmitted in infectious co-infected individuals.

-

2.

In line with the above assumption, the co-infection disease induced rate is taken as the mortality rate of the disease which has the within-host competitive advantage. This implies that, if , then is taken as , and if , then is taken as .

-

3.

Following the approach in [55], we assume the modification parameter which accounts for the assumed reduction of susceptibility to COVID-19 individuals who are already infected with influenza, while represents the assumed reduction of susceptibility to influenza individuals who are already infected with COVID-19.

-

4.

Contrary to the assumption of [53], we assume that the individuals that recovered from COVID-19 only develop a temporary immunity. This means that such individuals return to the susceptible class at the rate . Similarly, individuals who recovered from influenza lose their immunity at the rate , thus the immunity waning rate of recovered individuals with co-infection is given as . The possibility of reinfection is justified by the reports of several studies like [46], [56], [57], [58], [59].

3. Model analysis

We carried out the qualitative analysis in this section to learn more about COVID-19 and influenza’s transmission dynamics in a population. These include establishing the existence and stability of steady-state solutions and estimating the threshold quantities. In addition, the possibility of a backward bifurcation is discussed. To achieve these, we first examine the COVID-19-only and influenza-only sub-models ((5), (17), respectively), and then present a generalized result of the co-infection model (2).

3.1. COVID-19 only model

The COVID-19 only sub-model is obtained by setting .

| (5) |

with the initial conditions . The force of infection is given as , where .

3.1.1. Positivity and boundedness of solutions

We show that the state variables of the COVID-19 only model (5) are non-negative for all time and that the feasible region is bounded for the model to be epidemiologically meaningful. As a result, the following conclusion can be drawn.

Theorem 1

The initial data for the COVID-19 only model satisfies , and , such that the solutions of the model with positive initial data remain positive for all time .

Proof

Let , so that . By using the first equation of the sub-model (5), it follows that

(6) To solve the ordinary differential equation given in (6), we use the integrating factor method. As a result, this is written as

So that,

Hence,

Evidently, from the above inequality is positive. In the same way, the remaining state variables , , and , can be shown to be positive for all time . As a result, for all positive initial conditions, all solutions of the COVID-19 only model (5) remain positive. □

Furthermore, for the COVID-19 only model (5) to be mathematically and epidemiologically meaningful, system (5) must be considered in a biologically feasible region such that

The feasible region is positively invariant and attracts all the solutions of model (5). This implies that, all solutions that start in remain there for all time. Hence, the COVID-19 only sub-model is said to well-posed mathematically and epidemiologically.

3.1.2. Existence and stability of the COVID-19 free-equilibrium (CFE)

The disease-free equilibrium steady state henceforth refers to as COVID-19-free equilibrium steady state (CFE) is obtain by setting the right-hand side of all the equations in (5), and the infections variables to zero. Thus, the CFE denoted by is obtained as

| (7) |

To investigate the system’s stability, the threshold quantity called reproduction number is obtained by using the next-generation matrix operator as presented in [60], [61]. The Jacobian matrix of the new infection terms and the remaining transfer terms are obtained as

Hence, the reproduction number of the COVID-19 only model (5) defined as the highest eigenvalue of given by , is obtained as

| (8) |

The threshold quantity given in (8) is known as the control reproduction number, also called the effective reproduction number. It measures the average number of new secondary infections a single infected person can replicate during an infection period, in a population that is wholly susceptible in the presence of control measure (vaccination: in this study) [62]. Therefore, in the presence of COVID-19 vaccination, the threshold quantity in (8) measures the expected number of new COVID-19 cases that one COVID-infected individual can generate in a completely susceptible. By setting the control measure and its parameters to zero (i.e. ), the threshold quantity known as the basic reproduction number can be obtained such that

| (9) |

The basic reproduction number measures the average number of secondary cases produced by a single infected individual in a population that is completely susceptible, in a population without any control measure (see, for example, [63], [64], [65], [66], [67]). By following Theorem 2 of [68], the effective reproduction number (henceforth referred to as reproduction number) is used to establish the local stability of the COVID-19-free equilibrium . The Theorem below shows the result.

Theorem 2

The COVID-19-free equilibrium , of the model (5) is locally asymptotically stable in the biological feasible region if and unstable otherwise.

Proof

The Jacobian matrix of system (5) at the COVID-19 free-equilibrium was obtained as follows to prove the theorem above.

(10) Where , , , , , , , , and , while and are steady states given in (7). To establish the stability of the COVID-19-free equilibrium, it is necessary to show that the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are all negative. By using the matrix (10), the first eigenvalue is obtained as , while the remaining six eigenvalues are obtained from the reduced sub-matrix given below as

(11) According to the Routh–Hurwitz criterion, all the eigenvalues of the sub-matrix will be real and negative if and . By using the sub-matrix (11), we obtain the following

From the above results, if , and , all eigenvalues of the sub-matrix (10) are negative real part. As a result, the COVID-19 free-equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable but otherwise unstable. □

According to the epidemiological interpretation of Theorem 2, COVID-19 infection can be controlled in the population when and the initial sizes of the system (5) sub-population are in the region of attraction.

3.1.3. Existence of the endemic equilibria

The existence of the endemic equilibrium of COVID-19 only model (5) is derived in this section. The endemic equilibria denoted by is the steady state solution of the system in the presence of infection. For convenience, we define the force of infection as

| (12) |

where the total population , and the steady states solutions are obtained in the form of the force of infection as

| (13) |

where the constants , , and are given as

By substituting the above expressions (13) into the force of infection (12), the resulting polynomial is given as

| (14) |

where the coefficients of the polynomial equation are given as

| (15) |

The quadratic Eq. (14) is used to examine the possibilities of multiple endemic equilibria when the threshold quantity is less than unity. We note that the coefficient will always be positive for all positive parameter values, while the constant term will be negative if . Consequently, the result below follows

Theorem 3

The COVID-19 model (5) has

- (i)

a unique endemic equilibrium if or ;

- (ii)

a unique endemic equilibrium if , and either or ;

- (iii)

two endemic equilibria if , , and ;

- (iv)

no endemic equilibrium otherwise.

From the above Theorem 3, case (i) shows that the COVID-19 model (5) has a unique endemic equilibrium whenever . Furthermore, case (iii) suggests the possibility of backward bifurcation (the co-existence of the disease-free and a stable endemic equilibrium) when the associated threshold quantity is less than unity [69]. The epidemiological inference of backward bifurcation is that, while is required for disease elimination, it is insufficient. As a result, the elimination of the disease will be dependent on the initial sizes of the model’s sub-populations. To obtain the backward bifurcation point of system (5) when the threshold quantity , we set the discriminant and solve for the critical value of (represented by ) so that

| (16) |

Hence, it can be demonstrated that backward bifurcation occurs for values of when . The phenomenon of backward bifurcation in system (5) makes the control or elimination of COVID-19 challenging because the model’s reproduction number must be reduced to a level below unity such that . This means that in order to eradicate COVID-19 in the population, additional control measures will be required.

3.2. Influenza only model

Here, we note that setting in the co-infection model (2) results in the five compartmental influenza only model shown below.

| (17) |

with the initial conditions . The force of infection is given as , such that .

3.2.1. Positivity and boundedness of solutions

For the model to be epidemiologically meaningful, we show that the state variables of influenza only model (17) are non-negative for all time and that the feasible region is bounded.

Theorem 4

The initial data for the influenza only model satisfies , and , such that the solutions of the model with positive initial data remain positive for all time .

Proof

Let , so that . By using the first equation of the sub-model (17), consequently,

(18) The integrating factor method is used to solve the ordinary differential equation in (18). As a result, the following is written

As a result of which,

Thus,

As can be seen from the inequality above, is positive. Similarly, for all time , the remaining state variables , and , can be shown to be positive. As a result, all solutions of the influenza only model (17) remain positive for all positive initial conditions. □

Additionally, in order for the influenza only model (17) to be mathematically and epidemiologically meaningful, system (17) must be considered in a biologically feasible region such that

The feasible region is positively invariant and attracts all the solutions of model (17). This means that, all solutions that begin in remain there for all time. Thus, the influenza only sub-model is said to well-posed mathematically and epidemiologically.

3.2.2. Existence and stability of the influenza free-equilibrium (IFE)

We obtain the disease-free equilibrium steady state henceforth refers to as influenza-free equilibrium steady state (IFE) by setting the right-hand side of all the equations in (17) to zero, as well as the infections variables . Thus, the IFE denoted by is obtained as

| (19) |

Following the same approach in the previous section, the reproduction number is obtained by using the next-generation matrix operator to investigate the system’s stability. The Jacobian matrix for the new infection terms and the remaining transfer terms is given as

Using the above matrices, the reproduction number of the influenza only model (17) defined as the highest eigenvalue of given by , is obtained as

| (20) |

The threshold quantity given in (20) is known as the control reproduction number or effective reproduction number which measures the expected number of new influenza cases that one influenza-infected individual can generate in a completely susceptible population. Another threshold quantity known as the basic reproduction number can be obtained by setting the control measure and its parameters to zero (i.e. ). Consequently,

| (21) |

The basic reproduction number measures the average number of secondary cases produced by a single infected individual in a population that is completely susceptible, in a population without any influenza control measure. By following the same approach in the previous section, the effective reproduction number (henceforth referred to as the reproduction number) is used to establish the local stability of the influenza-free equilibrium . The Theorem below shows the result.

Theorem 5

The influenza-free equilibrium , of the model (17) is locally asymptotically stable in the biological feasible region if and unstable otherwise.

Proof

The Jacobian matrix of system (5) at the influenza free-equilibrium was obtained as follows to prove the theorem above.

(22) where , , , , , and , while and are steady states given in (19). To establish the stability of the influenza-free equilibrium, we show that the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix are all negative. By using the matrix (22), the first eigenvalue is obtained as , while the remaining four eigenvalues are obtained from the reduced sub-matrix given below as

(23) According to the Routh–Hurwitz criterion, all the eigenvalues of the sub-matrix will be real and negative if and . By using the sub-matrix (23), the following are obtained

From the above results, if , and , all eigenvalues of the sub-matrix (22) are negative real part. As a result, the influenza free-equilibrium is locally asymptotically stable but otherwise unstable. □

Based on the epidemiological interpretation of Theorem 5, influenza infection can be controlled in the population when and the initial sizes of the system (17) sub-population are in the region of attraction.

3.2.3. Existence of the endemic equilibria

In this section, we obtain the endemic equilibrium of influenza only model (17). The endemic equilibria denoted by is the steady state solution of the system in the presence of influenza infection. For convenience, we define the force of infection as

| (24) |

where the total population , and the steady states solutions are obtained in the form of the force of infection as

| (25) |

where the constants , , and are given as

By substituting the above expressions (25) into the force of infection (24), the resulting polynomial is given as

| (26) |

where the coefficients of the polynomial equation are given as

| (27) |

We use the quadratic Eq. (26) to analyze the possibilities of multiple endemic equilibria when the threshold quantity is less than unity. It is important to note that the coefficient will always be positive for all non-negative parameter values, while the constant term will be negative if . Consequently, the result below follows

Theorem 6

The influenza-only model (17) has

- (i)

a unique endemic equilibrium if or ;

- (ii)

a unique endemic equilibrium if , and either or ;

- (iii)

two endemic equilibria if , , and ;

- (iv)

no endemic equilibrium otherwise.

From the above Theorem 6, case (i) indicates that the influenza-only model (17) has a unique endemic equilibrium whenever . In addition, case (iii) suggests the possibility of backward bifurcation when . To obtain the backward bifurcation point of system (17) when the threshold quantity , we set the discriminant and solve for the critical value of (denoted by ) so that

| (28) |

Hence, it can be demonstrated that backward bifurcation occurs for values of when . The phenomenon of backward bifurcation in system (17) makes the control or elimination of influenza challenging because the model’s reproduction number must be reduced largely below unity such that . This means that in order to eradicate influenza, additional control measures will be required.

3.3. COVID-19-influenza co-infection model

In this section, we only investigate the existence and stability of the disease-free equilibrium for the sake of simplicity. We consider the co-infection model (2) on the feasible region such that

where is as given in (1). Following the same approach in the previous sections, it can be shown that the region is positively invariant and attracts all solutions of the model (2). As a result, the COVID-19-influenza co-infection model (2) is said to be mathematically and epidemiologically well-posed in the feasible region .

3.3.1. Existence and stability of the disease-free equilibrium

The disease-free equilibrium of the COVID-19-influenza co-infection model (2) denoted by is given below as , where , and

| (29) |

such that

Following the derivation of the reproduction numbers for the COVID-19 only and influenza-only sub-models, the reproduction number of the co-infection model system (2) is given by

| (30) |

where and are the associated reproduction number for COVID-19 and influenza respectively. Hence, the following result follows.

Theorem 7

The disease-free equilibrium , of the COVID-19-influenza co-infection model (2) is locally asymptotically stable in the feasible region if the threshold quantity and unstable otherwise.

4. Optimal control model

Since the modeling of infectious diseases may involve a high number of constant parameters, it is necessary to investigate disease dynamics with optimal control interventions in order to make model predictions realistic [70]. To accomplish this, the optimal control theory is used to recommend the most effective strategy for reducing the disease burden in the population. In this section, the impact of implementing three multiple time-dependent control variables (classified as vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions) on reducing COVID-19 and influenza in the population is investigated. The time-dependent control variables , , and introduced into the co-infection model (2) are described as follows:

-

1.

The non-pharmaceutical interventions for preventive strategy targeted at preventing the transmission of both COVID-19 and influenza from infectious individuals are denoted by the control function . This can be accomplished through educational campaigns and public awareness about good personal hygiene, the use of facial masks, and the use of physical or social distancing protocols, as suggested in [1], [47]. We note that when , the control strategy is effective at preventing infection, whereas when , this indicates that the strategy fails or is ineffective.

-

2.

The control functions , and are introduced by replacing the respective constant vaccination parameters , and . As a result, the control function represent the time-dependent vaccination rate of susceptible individuals against COVID-19, and the time-dependent vaccination rate of susceptible individuals against influenza is represented by the control function .

Following the above descriptions, the optimal control co-infection model with the three time-dependent variables is given below

| (31) |

We note that the optimal control model (31) has the same initial conditions as (3), and the control variable is defined as . In addition, the forces of infection , , , and are the same as in (4). The purpose of introducing the time dependent control variables is to minimize the abundance of infectious humans that are responsible for the spread of the infection in the population at a minimum cost. It is imperative to mention that the impact of maximizing the control interventions on disease burden can also be examined. Thus, we consider the objective functional defined as

| (32) |

where is the final time for control implementation, in the sense that . The positive weight constants represented by , and for are used to balance the relative functions of each term. The first component of the objective functional represents the cost related to the existing number of exposed and infectious people in the domain, while the second component is the total control implementation cost to attain the eradication of COVID-19 and influenza. We note that the cost control functions in this study take a quadratic form, such that represents the cost control function for non-pharmaceutical interventions, while the terms , and represent the cost control functions associated with vaccination against COVID-19 and influenza respectively. The controls in the objective functional are quadratic since the costs of these interventions are nonlinear. This choice is based on prior research that suggests there are no direct correlations between the effects of interventions, and it costs on the infected populations (see [71], [72], [73] and the references therein). Now, we seek a triple optimal control that satisfies the minimization problem given by

| (33) |

where is the non-empty control set given as . The sufficient condition to obtain the optimal control for will obtained by using the Pontryagin’s maximum principle [74]. To do this, the control minimization problem (33) subject to the optimal control system (31) is transformed into a problem of minimizing pointwise Hamiltonian such that the resulting Hamiltonian equation denoted by is given by

| (34) |

where for are the adjoint functions associated with the state variables of the optimal control model in (31), while for is the right-hand side of the differential equations of the state variables in system (31). Thus, the expanded form of the Hamiltonian function in (34), is given by

| (35) |

In the next Theorem, we provide the characterization of the optimal control which satisfies the minimization problem (33) by following the method in [75].

Theorem 8

For an optimal control set ( , , ) that minimizes over , there exist an adjoint variables, which satisfy the system

(36)

Where

and

(37)

with transversality conditions , for all . Thus, the control set is characterized by

(38)

where and are as given in (37) , and

(39)

Proof

By using the Pontryagin’s maximum principle [75], there exist an adjoint variables obtained by computing the partial derivatives of system (35) with its state variables satisfying

with the transversality conditions , for all . Next, we differentiate the Hamiltonian with respect to the optimal control written as

Now, we obtain the characterization by imposing bounds on the controls via standard arguments, such that

(40) Where

It can be seen that , , and satisfies (38). Hence, this completes the proof. □

5. Numerical simulations and discussion

This section focuses on the numerical simulation of the co-dynamics of COVID-19 and influenza under different possible scenarios. We aim to provide the necessary conditions to reduce the burden of these diseases in the community. To achieve this, we simulate both the model without optimal control (2), and the model with optimal control (31) and their respective results are discussed in the following sub-sections. Unless otherwise stated, the model parameter values used in this section were obtained from various literature and are tabulated in Table 2. We note that all parameter values with units are in days. By using the baseline parameter values in Table 2, the respective reproduction numbers of COVID-19 and influenza are estimated as and .

5.1. Simulation of the model without optimal control

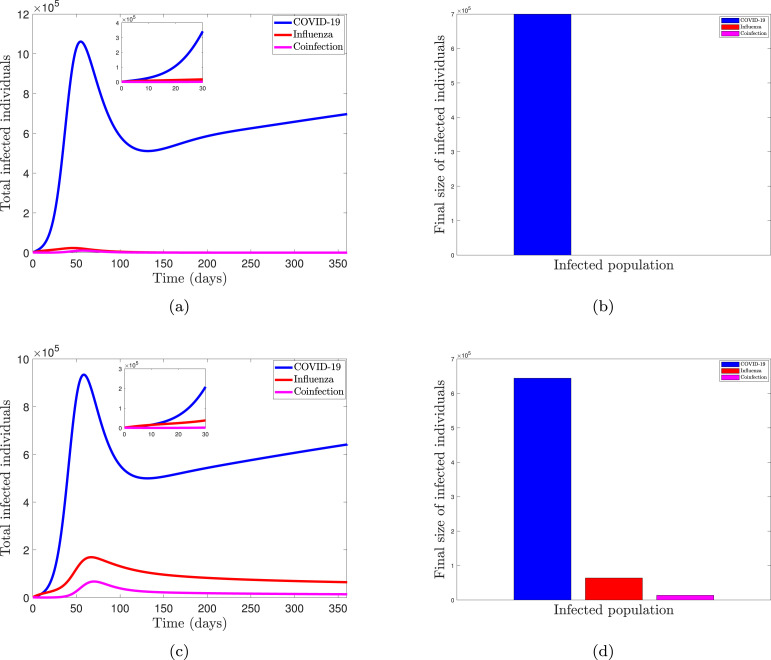

One of the arising questions in the modeling of co-infection disease is the competitive outcome of their co-dynamic behavior under different equilibrium states. Epidemiological speaking, disease is expected to be controlled in a population when the threshold quantity called reproduction number is less than unity, while the existence of such disease is possible otherwise [68], [76], [77]. In the case of the co-dynamics of two types (or strains) of disease, coexistence is expected in the population when each strain can invade the other. In other words, when the two diseases are at endemic equilibrium with reproduction numbers greater than unity, they are expected to co-exist [78]. However, for models with the possibility of super-infection dynamics, the replacement of a strain is dependent on the competitive outcomes at the within-host level. Thus, since the co-infection model (2) takes into account the super-infection dynamics (see model formulation assumption in Section 1), we shall investigate the impact of the within-host competitive outcome and the between-host competitive outcome on the co-dynamics of the diseases in the populace. The between-host advantage is characterized by the threshold quantity level between the two competing diseases, such that when the COVID-19 reproduction number is greater than the influenza reproduction number , then we say that COVID-19 has the between-host advantage over influenza disease, and vice-versa. Similarly, the within-host advantage is characterized by the transmission probabilities of the co-infected individuals respectively. In this case, when COVID-19 infection has a within-host advantage over influenza, it means that a susceptible individual will progress into the COVID-19 exposed population after effective contact with a co-infected person, and vice-versa. Fig. 2, Fig. 3 show the dynamic and final sizes of the total infected individuals under different scenarios. We note that the total infected individual of COVID-19 is defined as the sum of exposed, asymptomatic infectious, symptomatic infectious, and hospitalized individuals for COVID-19 , the total infected individuals of influenza is , and total co-infected individuals are .

Fig. 2.

Simulation of model (2) showing the dynamics and final sizes of the total infected individuals when , with . Parameters are at baseline values except for . (a, b) COVID-19 has the within-host advantage , with (); (c, d) Influenza has the within-host advantage , with ().

Fig. 3.

Simulation of model (2) showing the dynamics and final sizes of the total infected individuals when , with . Parameters are at baseline values except for . (a, b) Influenza has the within-host advantage , with (); (c, d) COVID-19 has the within-host advantage , with ().

We simulate the effect of the within-host advantage on the total size of the infected population in Fig. 2 while keeping the between-host advantage of COVID-19 over influenza (i.e., the reproduction number of COVID-19 is higher than that of influenza). The population dynamic when COVID-19 has the between-host and within-host advantage over the competing disease is depicted in Fig. 2(a). The system exhibits competitive exclusion, as evidenced by the results. To put it another way, COVID-19 dominates the population while eradicating influenza. As a result, the number of people infected with influenza and those who were co-infected with the virus plummeted and eventually vanished. When influenza has a competitive advantage within the host over COVID-19, however, the system’s dynamics change. As shown in Fig. 2(b), this advantage allows diseases to compete in the environment, allowing COVID-19 and influenza to coexist. Even though COVID-19 infection is prevalent in the population, influenza is not eradicated. In general, we can deduce from the results in Fig. 2 that the between-hosts and within-host competitive advantages have a significant impact on the system’s dynamic. As a result, in Fig. 3, we examine the impact of the within-host advantage on the infected population while maintaining influenza’s between-host advantage over COVID-19 (i.e., the reproduction number of influenza is greater than that of COVID-19). In comparison to the values in Fig. 2, we increase the threshold quantity and within-host parameter values to more effectively investigate the effect of the within-host advantage.

The model system exhibits disease coexistence when the diseases are in their endemic states, as shown in Fig. 3(a). Because influenza has a reproduction number advantage as well as a within-host advantage, it dominates in the population. However, we note that this does not drive the competing disease into extinction as observed in the case of Fig. 2(a). The variability in the threshold quantity and within-host parameter values used can cause this change in dynamic. The system shows a trade-off mechanism in Fig. 3(b), which allows disease replacement in the population. Even though influenza has a higher reproduction number than COVID-19, this mechanism occurs because COVID-19 has a competitive advantage within the host. In comparison to Fig. 2, the result from Fig. 3 has a slight difference in system dynamics. Changes in the reproduction number values and the within-host advantage parameter values (i.e. ), can be linked to these dynamics. As a result of these findings, we can deduce that the transmission probabilities of the two diseases, as well as the threshold quantities, determine the disease’s competitive dynamics in the population. Because of the varying dynamics of the infected population, it is important to control disease epidemics by reducing disease transmission. The next section will look at how to keep COVID-19 and influenza at bay in the population.

5.2. Simulation of the optimal control model

We investigate the impact of optimum control strategies in mitigating COVID-19 and influenza in the general population by numerically solving the optimal control model. To achieve this, we use the forward–backward sweep method to solve the optimality system (31) and the adjoint system (36) along with the characterization (38) for 350 days of control intervention. We assumed and set the positive weight constants , , and in the objective function to one for simulation purposes, ensuring that none of the three terms is dominant. In addition, , and are assumed for the weight constants associated with the total costs of implementing controls. Unless otherwise specified, the parameter values used are listed in Table 2, such that the threshold quantities and in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10. The controlled model will be simulated in three different scenarios. Single control intervention, twofold control intervention, and threefold control intervention are examples of these. The term “single control” refers to the fact that only one intervention can be carried out at a time. There are three strategies in this scenario: A, B, and C. The second scenario (dual control) entails the implementation of two control interventions at the same time. Strategy D, Strategy E, and Strategy F are all included in this scenario. Finally, the third scenario (threefold control) is used to examine the impact of combining all three controls considered in this study. In Strategy G, this is depicted. The dynamics of total infected populations under various control strategies are discussed in the following sections.

Fig. 4.

Simulations of the impact of control strategy A on (a) total COVID-19 infected people, (b) total influenza-infected people, and (c) total co-infected people.

Fig. 5.

Simulations of the impact of control strategy B on (a) total COVID-19 infected people, (b) total influenza-infected people, and (c) total co-infected people.

Fig. 6.

Simulations of the impact of control strategy C on (a) total COVID-19 infected people, (b) total influenza-infected people, and (c) total co-infected people.

Fig. 7.

Simulations of the impact of control strategy D on (a) total COVID-19 infected people, (b) total influenza-infected people, and (c) total co-infected people.

Fig. 8.

Simulations of the impact of control strategy E on (a) total COVID-19 infected people, (b) total influenza-infected people, and (c) total co-infected people.

Fig. 9.

Simulations of the impact of control strategy F on (a) total COVID-19 infected people, (b) total influenza-infected people, and (c) total co-infected people.

Fig. 10.

Simulations of the impact of control strategy G on (a) total COVID-19 infected people, (b) total influenza-infected people, and (c) total co-infected people.

5.2.1. Strategy A: Optimal use of non-pharmaceutical interventions only

We illustrate the effect of the optimal use of non-pharmaceutical interventions such as personal hygiene, facial mask, and social distancing on the total size of infected individuals in the population. The goal of the intervention is to reduce coronavirus and influenza infection transmission from an infected person. As shown graphically in Fig. 4, this control intervention is effective in reducing the magnitude of infected people. Particularly, Fig. 4(a) depicts a significant reduction in the size of the population infected with COVID-19, while Fig. 4(b) depicts a reduction in the number of infected influenza individuals. Similarly, Fig. 4(c) shows a significant decrease in the number of co-infected people. As a result of this finding, we can conclude that, when compared to a scenario without control, the optimal use of non-pharmaceutical interventions will greatly aid in reducing the burden of COVID-19 and influenza in the community.

5.2.2. Strategy B: Optimal use of vaccination against COVID-19 only

A simulation of the impact of COVID-19 vaccination solely on the size of the infected population is shown in Fig. 5. As shown in Figs. 5(a) to 5(c), there is a decrease in all infected populations throughout the intervention period. Although, as shown in Fig. 5(a), the number of averted individuals appears to be lower when compared to the optimal use of non-pharmaceutical intervention alone. Given the flaws in the COVID-19 vaccine, this outcome seems reasonable. Because the vaccine is imperfect, people who have been vaccinated have a lower risk of infection, but they can still contract COVID-19 after coming into contact with an infectious person. As a result, combining this intervention with other control measures that reduce the infection’s transmission rate will be beneficial in effectively controlling the spread of this disease.

5.2.3. Strategy C: Optimal use of vaccination against influenza only

Here, the impact of optimal use of vaccination against influenza only on the infected population is presented. The result shows that influenza vaccination reduces not only the influenza-infected population but also the total population of COVID-19 and co-infected individuals as shown in Fig. 6. When compared to a scenario without control, this intervention aids in the reduction of influenza and co-infected population faster, as shown in Fig. 6, Fig. 6 respectively. As previously stated, combining this intervention with other control measures that reduce the transmission rate of the infection will help to effectively control disease spread.

5.2.4. Strategy D: Combination of the optimal controls and only

We investigate the effect of combining different single controls in controlling the spread of COVID-19 and influenza over time, based on the results from the use of single control intervention on the reduction of infected populations depicted in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6. The impact of combining only non-pharmaceutical intervention and COVID-19 vaccination on reducing the burden of these diseases in the community is shown in Fig. 7. When compared to a scenario with a single control intervention or no control intervention, the result shows that this combination of controls aids in the reduction of the infected population faster. As a result of these findings, we can conclude that implementing non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccination against the deadly COVID-19 disease will significantly reduce the burden of both COVID-19 and influenza in the general population.

5.2.5. Strategy E: Combination of the optimal controls and only

In Fig. 8, we show how combining only non-pharmaceutical intervention and influenza vaccination reduces the burden of these diseases in the community, similar to the investigation of the effect of double control intervention shown in Fig. 7. When compared to a scenario with a single control intervention or no control intervention, a combination of non-pharmaceutical intervention and influenza vaccination aids in the faster reduction of the infected population, as shown in Fig. 7. As a result of these findings, we can deduce that non-pharmaceutical interventions and influenza vaccination will significantly reduce the burden of COVID-19 as well as influenza in the general public.

5.2.6. Strategy F: Combination of the optimal controls and only

We used a combination of COVID-19 vaccination and influenza vaccination in this strategy to reduce the spread of these diseases in the population. Fig. 9 depicts the dynamics of infected populations. When compared to a scenario without control, the result shows that this intervention strategy reduces the infected population faster. From Fig. 9(a), an additional control strategy will be required to reduce the size of COVID-19 infected people. Thus, combining these interventions with other control measures aimed at reducing COVID-19 infection transmission will aid in effectively controlling the disease’s spread in the populace.

5.2.7. Strategy G: Combination of all the optimal controls , , and

We simulate the effect of combining all of the control strategies (non-pharmaceutical intervention , COVID-19 vaccination , and influenza vaccination ) on the infected population, as suggested by the results of all of the above strategies. Combining all of the control strategies, as shown in Fig. 10, greatly reduces the number of infected individuals. We can see a significant reduction in the total size of infected COVID-19 individuals in Fig. 10(a) when compared to other strategies. This finding suggests that non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccination against COVID-19 and influenza are critical for effectively controlling COVID-19 and influenza in the general public.

6. Conclusion and recommendations

In this study, a fifteen compartmental deterministic model was developed and critically analyzed to investigate the co-dynamics of COVID-19 and influenza in a population. The COVID-19-only and influenza-only sub-models were first analyzed, and thereafter a generalized result was presented for the full co-infection model. We show that when the associated reproduction numbers and are less than unity, the COVID-19 free equilibrium (CFE) and influenza-free equilibrium (IFE) are locally asymptomatically stable, and unstable otherwise. The endemic equilibria of the two sub-models were obtained, and the conditions for the phenomenon of backward bifurcation were discussed. The COVID-19-only model is said to undergo a backward bifurcation when the condition is met. Similarly, the influenza-only model will exhibit a backward bifurcation when . The phenomenon of backward bifurcation in system (5), (17) respectively, will make the control or elimination of COVID-19 and influenza difficult since the reproduction numbers must be reduced significantly below unity such that the conditions and are achieved. As a result, an additional control strategy for COVID-19 and influenza epidemic control will be required. The COVID-19-influenza co-infection model’s generalized analytical result is presented. The system (2) is said to be locally asymptotically stable when the threshold quantity is less than unity.

The optimal control model was obtained by introducing the three time-dependent control functions , , and into the model system (2). The time-dependent control represents the non-pharmaceutical interventions for preventive strategy against COVID-19 and influenza. Examples of these strategies include personal hygiene, the use of facial masks, and social distancing protocols. The Pontryagin’s Maximum Principle is used to determine the necessary conditions for the existence of optimal control and the optimality system for the model. A numerical simulation was run using both the model without optimal control (2) and the optimal control model (31) to determine the necessary conditions for reducing the disease burden. The model system (2) was simulated to investigate the co-dynamics of COVID-19 and influenza under different conditions. One of these conditions is the influence of competitive outcomes between-hosts and within-hosts. We conclude from the results that the disease’s competitive dynamics in the population are determined by the transmission probabilities of the two diseases, as well as the threshold quantities. As a result, significantly reducing the fitness of threshold quantities and minimizing the disease transmission rate will be critical in effectively reducing the disease burden.

For the optimal control model, the forward–backward sweep method was used to solve the optimality system (31) and the adjoint system (36) along with the characterization (38). We simulate three scenarios that constitute seven strategies to determine the optimum control suitable for controlling the prevalence of COVID-19 and influenza. The findings show that, while single and twofold control interventions can be used to reduce disease, the threefold control intervention, which incorporates all three controls, will be the most effective in reducing COVID-19 and influenza in the population. In comparison to competing strategies, the magnitude of the infected populations for COVID-19, influenza, and co-infection is reduced more quickly, as shown in Fig. 10. Additionally, the three control interventions gradually reduce the number of infected people to zero. Based on the results of the optimal control problem simulations, it is recommended that a combination of non-pharmaceutical intervention, COVID-19 vaccination, and influenza vaccination be used to effectively control the spread of COVID-19 and influenza in the population. Because each disease vaccine has no cross-immunity against others, Strategy G, as shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6, Fig. 7, Fig. 8, Fig. 9, Fig. 10, will be the most effective in controlling disease spread. A future study will concentrate on cost-effective analysis to investigate the most cost-effective strategy suitable for use among various combinations of control strategies. It is important to note that controlling and eradicating any form of disease in a large population can both be severe and expensive. The extended study would provide information to health policymakers in developing nations about various control strategies that can be combined to reduce COVID-19 and influenza at a low cost that each nation can afford. One of the limitations of this study is the use of some assumed parameter values which are not in literatures, particularly, the co-infected parameters value. Enhancing collaborations with modelers and health practitioners can help in reporting and use of real co-infected parameter values which will allow more realistic result in simulations. In addition, the optimal control section focuses on minimizing the infected population alone, more study can focus on investigating the impact of maximizing control interventions like vaccination.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Mayowa M. Ojo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis. Temitope O. Benson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Olumuyiwa James Peter: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft. Emile Franc Doungmo Goufo: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The first author (MMO) would like to thank Latavia Hill of the Department of Microbiology at the University of Kansas for several discussions on the COVID-19 and influenza co-infections within-host dynamics, which led to this work.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Adeniyi M.O., Oke S.I., Ekum M.I., Benson T., Adewole M.O. Modeling, Control and Drug Development for COVID-19 Outbreak Prevention. Springer; 2022. Assessing the impact of public compliance on the use of non-pharmaceutical intervention with cost-effectiveness analysis on the transmission dynamics of COVID-19: Insight from mathematical modeling; pp. 579–618. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tchoumi S.Y., Diagne M.L., Rwezaura H., Tchuenche J.M. Malaria and COVID-19 co-dynamics: A mathematical model and optimal control. Appl. Math. Model. 2021;99:294–327. doi: 10.1016/j.apm.2021.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ullah S., Khan M.A. Modeling the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on the dynamics of novel coronavirus with optimal control analysis with a case study. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;139 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lemecha Obsu L., Feyissa Balcha S. Optimal control strategies for the transmission risk of COVID-19. J. Biol. Dyn. 2020;14(1):590–607. doi: 10.1080/17513758.2020.1788182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shen Z.-H., Chu Y.-M., Khan M.A., Muhammad S., Al-Hartomy O.A., Higazy M. Mathematical modeling and optimal control of the COVID-19 dynamics. Results Phys. 2021;31 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.105028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J., Wang R., Gilby N.B., Wei G.-W. Omicron variant (B. 1.1. 529): Infectivity, vaccine breakthrough, and antibody resistance. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2022 doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.1c01451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sonabend R., Whittles L.K., Imai N., Perez-Guzman P.N., Knock E.S., Rawson T., Gaythorpe K.A.M., Djaafara B.A., Hinsley W., FitzJohn R.G., et al. Non-pharmaceutical interventions, vaccination, and the SARS-CoV-2 delta variant in England: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet. 2021;398(10313):1825–1835. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02276-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mlcochova P., Kemp S., Dhar M.S., Papa G., Meng B., Mishra S., Whittaker C., Mellan T., Ferreira I., Datir R., et al. 2021. SARS-CoV-2 B. 1.617. 2 delta variant emergence and vaccine breakthrough. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Derouich M., Boutayeb A. An avian influenza mathematical model. Appl. Math. Sci. 2008;2(36):1749–1760. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smieszek T., Lazzari G., Salathé M. Assessing the dynamics and control of droplet-and aerosol-transmitted influenza using an indoor positioning system. Sci. Rep. 2019;9(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-38825-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karim S.A.A., Razali R. A proposed mathematical model of influenza A, H1N1 for Malaysia. J. Appl. Sci. 2011;11(8):1457–1460. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jung E., Iwami S., Takeuchi Y., Jo T.-C. Optimal control strategy for prevention of avian influenza pandemic. J. Theoret. Biol. 2009;260(2):220–229. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee S., Chowell G., Castillo-Chávez C. Optimal control for pandemic influenza: The role of limited antiviral treatment and isolation. J. Theoret. Biol. 2010;265(2):136–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Konala V.M., Adapa S., Gayam V., Naramala S., Daggubati S.R., Kammari C.B., Chenna A. Co-infection with influenza A and COVID-19. Eur. J. Case Rep. Intern. Med. 2020;7(5) doi: 10.12890/2020_001656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuadrado-Payán E., Montagud-Marrahi E., Torres-Elorza M., Bodro M., Blasco M., Poch E., Soriano A., Piñeiro G.J. SARS-CoV-2 and influenza virus co-infection. Lancet. 2020;395(10236) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31052-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agarwal A., Agarwal M., Sharma A., Jakhar R. Impact of influenza A co-infection with COVID-19. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung. Dis. 2021;25:413–415. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.21.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peter O.J., Qureshi S., Yusuf A., Al-Shomrani M., Idowu A.A. A new mathematical model of COVID-19 using real data from Pakistan. Results Phys. 2021;24 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kucharski A.J., Russell T.W., Diamond C., Liu Y., Edmunds J., Funk S., Eggo R.M., Sun F., Jit M., Munday J.D., et al. Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet. Infect. Dis. 2020;20(5):553–558. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30144-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ivorra B., Ferrández M.R., Vela-Pérez M., Ramos A.M. Mathematical modeling of the spread of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) taking into account the undetected infections. The case of China. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2020;88 doi: 10.1016/j.cnsns.2020.105303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ndaïrou F., Area I., Nieto J.J., Torres D.F.M. Mathematical modeling of COVID-19 transmission dynamics with a case study of Wuhan. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;135 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.109846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cakir Z., Savas H.B. A mathematical modelling approach in the spread of the novel 2019 coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic. Electron. J. Gen. Med. 2020;17(4):em205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peter O.J., Shaikh A.S., Ibrahim M.O., Nisar K.S., Baleanu D., Khan I., Abioye A.I. Analysis and dynamics of fractional order mathematical model of COVID-19 in Nigeria using atangana-baleanu operator. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2021:1823–1848. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell T.W., Wu J.T., Clifford S., Edmunds W.J., Kucharski A.J., Jit M., et al. Effect of internationally imported cases on internal spread of COVID-19: A mathematical modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(1):e12–e20. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30263-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Flahault A., Vergu E., Coudeville L., Grais R.F. Strategies for containing a global influenza pandemic. Vaccine. 2006;24(44–46):6751–6755. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baba I.A., Ahmad H., Alsulami M.D., Abualnaja K.M., Altanji M. A mathematical model to study resistance and non-resistance strains of influenza. Results Phys. 2021;26 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kharis M., Arifudin R. Mathematical model of seasonal influenza epidemic in central Java with treatment action. Int. J. Pure Appl. Math. 2017;112(3):571–588. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tchuenche J.M., Khamis S.A., Agusto F.B., Mpeshe S.C. Optimal control and sensitivity analysis of an influenza model with treatment and vaccination. Acta Biotheor. 2011;59(1):1–28. doi: 10.1007/s10441-010-9095-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain T., Ozair M., Oare Okosun K., Ishfaq M., Ullah Awan A., Aslam A. Dynamics of swine influenza model with optimal control. Adv. Difference Equ. 2019;2019(1):1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gweryina R.I., Madubueze C.E., Kaduna F.S. Mathematical assessment of the role of denial on COVID-19 transmission with non-linear incidence and treatment functions. Sci. Afr. 2021;12 doi: 10.1016/j.sciaf.2021.e00811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ojo M.M., Benson T.O., Shittu A.R., Doungmo Goufo E.F. Optimal control and cost-effectiveness analysis for the dynamic modeling of Lassa fever. J. Math. Comput. Sci. 2022;12:Article–ID. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diagne M.L., Rwezaura H., Tchoumi S.Y., Tchuenche J.M. A mathematical model of COVID-19 with vaccination and treatment. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/1250129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ojo M.M., Goufo E.F.D. Mathematical analysis of a Lassa fever model in Nigeria: Optimal control and cost-efficacy. Int. J. Dyn. Control. 2022:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Agusto F., Numfor E., Srinivasan K., Iboi E., Fulk A., Saint Onge J.M., Peterson T. 2021. Impact of public sentiments on the transmission of COVID-19 across a geographical gradient. MedRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ojo M.M., Peter O.J., Goufo E.F.D., Panigoro H.S., Oguntolu F.A. Mathematical model for control of tuberculosis epidemiology. J. Appl. Math. Comput. 2022:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olaniyi S., Obabiyi O.S., Okosun K.O., Oladipo A.T., Adewale S.O. Mathematical modelling and optimal cost-effective control of COVID-19 transmission dynamics. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2020;135(11):938. doi: 10.1140/epjp/s13360-020-00954-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pulliam J.R.C., van Schalkwyk C., Govender N., von Gottberg A., Cohen C., Groome M.J., Dushoff J., Mlisana K., Moultrie H. 2021. Increased risk of SARS-CoV-2 reinfection associated with emergence of the Omicron variant in South Africa. MedRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brandal L.T., MacDonald E., Veneti L., Ravlo T., Lange H., Naseer U., Feruglio S., Bragstad K., Hungnes O., Ødeskaug L.E., et al. Outbreak caused by the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant in Norway, November to December 2021. Eurosurveillance. 2021;26(50) doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2021.26.50.2101147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rubin R. What happens when COVID-19 collides with flu season? JAMA. 2020;324(10):923–925. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.15260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osman M., Klopfenstein T., Belfeki N., Gendrin V., Zayet S. A comparative systematic review of COVID-19 and influenza. Viruses. 2021;13(3):452. doi: 10.3390/v13030452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tomassini S., Kotecha D., Bird P.W., Folwell A., Biju S., Tang J.W. Setting the criteria for SARS-CoV-2 reinfection–six possible cases. J. Infect. 2021;82(2):282–327. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alizon S. Co-infection and super-infection models in evolutionary epidemiology. Interface Focus. 2013;3(6) doi: 10.1098/rsfs.2013.0031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dadashi M., Khaleghnejad S., Abedi Elkhichi P., Goudarzi M., Goudarzi H., Taghavi A., Vaezjalali M., Hajikhani B. COVID-19 and influenza co-infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Med. 2021;8:971. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.681469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh B., Kaur P., Reid R.-J., Shamoon F., Bikkina M. COVID-19 and influenza co-infection: Report of three cases. Cureus. 2020;12(8) doi: 10.7759/cureus.9852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pusparani A., Henrina J., Cahyadi A. Co-infection of COVID-19 and recurrent malaria. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021;15(05):625–629. doi: 10.3855/jidc.13793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iboi E.A., Ngonghala C.N., Gumel A.B. Will an imperfect vaccine curtail the COVID-19 pandemic in the US? Infect. Dis. Model. 2020;5:510–524. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mancuso M., Eikenberry S.E., Gumel A.B. Will vaccine-derived protective immunity curtail COVID-19 variants in the US? Infect. Dis. Model. 2021;6:1110–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2021.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gumel A.B., Iboi E.A., Ngonghala C.N., Ngwa G.A. 2021. Mathematical assessment of the roles of vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 dynamics: A multigroup modeling approach. MedRxiv, 2020–2012. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Agusto F.B., Erovenko I.V., Fulk A., Abu-Saymeh Q., Romero-Alvarez D.D., Ponce J., Sindi S., Ortega O., Saint Onge J.M., Peterson A.T. 2020. To isolate or not to isolate: The impact of changing behavior on COVID-19 transmission. MedRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jin Z., Zhang J., Song L.-P., Sun G.-Q., Kan J., Zhu H. Modelling and analysis of influenza A (H1N1) on networks. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S1-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kanyiri C.W., Mark K., Luboobi L. Mathematical analysis of influenza A dynamics in the emergence of drug resistance. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/2434560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tchuenche J.M., Dube N., Bhunu C.P., Smith R.J., Bauch C.T. The impact of media coverage on the transmission dynamics of human influenza. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S1-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wessel L., Hua Y., Wu J., Moghadas S.M. Public health interventions for epidemics: Implications for multiple infection waves. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Brozak S.J., Pant B., Safdar S., Gumel A.B. Dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic in India and Pakistan: A metapopulation modelling approach. Infect. Dis. Model. 2021;6:1173–1201. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2021.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.David J.F., Iyaniwura S.A., Yuan P., Tan Y., Kong J.D., Zhu H. 2021. Modeling the potential impact of indirect transmission on COVID-19 epidemic. MedRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ojo M.M. University of Kansas; 2019. Mathematical Modeling of Neisseria Meningitidis: A Case Study of Nigeria. (Ph.D. thesis) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention M.M. 2022. Reinfection with COVID-19. Available from: https://www.Cdc.Gov/Coronavirus/2019-Ncov/Your-Health/Reinfection.html. (Accessed 11 January 2022) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stokel-Walker C. What we know about COVID-19 reinfection so far. BMJ. 2021;372 doi: 10.1136/bmj.n99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Davies J.R., Grilli E.A., Smith A.J. Influenza A: Infection and reinfection. Epidemiol. Infect. 1984;92(1):125–127. doi: 10.1017/s002217240006410x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Memoli M.J., Han A., Walters K.-A., Czajkowski L., Reed S., Athota R., Angela Rosas L., Cervantes-Medina A., Park J.-K., Morens D.M., et al. Influenza A reinfection in sequential human challenge: Implications for protective immunity and “universal” vaccine development. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020;70(5):748–753. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciz281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oke S.I., Ojo M.M., Adeniyi M.O., Matadi M.B. Mathematical modeling of malaria disease with control strategy. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. 2020;2020:Article–ID. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ojo M.M., Gbadamosi B., Benson T.O., Adebimpe O., Georgina A.L. Modeling the dynamics of Lassa fever in Nigeria. J. Egyptian Math. Soc. 2021;29(1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gumel A.B., McCluskey C.C., Watmough J. An SVEIR model for assessing potential impact of an imperfect anti-SARS vaccine. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2006;3(3):485. doi: 10.3934/mbe.2006.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Akinpelu F.O., Ojo M.M. A mathematical model for the dynamic spread of infection caused by poverty and prostitution in Nigeria. Int. J. Math. Phys. Sci. Res. 2016;4:33–47. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goufo E.F.D., Pene M.K., Mugisha S. Stability analysis of epidemic models of Ebola hemorrhagic fever with non-linear transmission. J. Nonlinear Sci. Appl. 2016;9(6):4191–4205. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Peter O.J., Abioye A.I., Oguntolu F.A., Owolabi T.A., Ajisope M.O., Zakari A.G., Shaba T.G. Modelling and optimal control analysis of Lassa fever disease. Inform. Med. Unlocked. 2020;20 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gbadamosi B., Ojo M.M., Oke S.I., Matadi M.B. Qualitative analysis of a Dengue fever model. Math. Comput. Appl. 2018;23(3):33. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ojo M.M., Goufo E.F.D. Assessing the impact of control interventions and awareness on malaria: A mathematical modeling approach. Commun. Math. Biol. Neurosci. 2021;2021:Article–ID. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van den Driessche P., Watmough J. Reproduction numbers and sub-threshold endemic equilibria for compartmental models of disease transmission. Math. Biosci. 2002;180(1–2):29–48. doi: 10.1016/s0025-5564(02)00108-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ojo M.M., Goufo E.F.D. Modeling, analyzing and simulating the dynamics of Lassa fever in Nigeria. J. Egyptian Math. Soc. 2022;30(1):1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rajput A., Sajid M., Shekhar C., Aggarwal R., et al. Optimal control strategies on COVID-19 infection to bolster the efficacy of vaccination in India. Sci. Rep. 2021;11(1):1–18. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-99088-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Agusto F.B., Leite M.C.A. Optimal control and cost-effective analysis of the 2017 meningitis outbreak in Nigeria. Infect. Dis. Model. 2019;4:161–187. doi: 10.1016/j.idm.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abioye A.I., Peter O.J., Ogunseye H.A., Oguntolu F.A., Oshinubi K., Ibrahim A.A., Khan I. Mathematical model of COVID-19 in Nigeria with optimal control. Results Phys. 2021;28 doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]