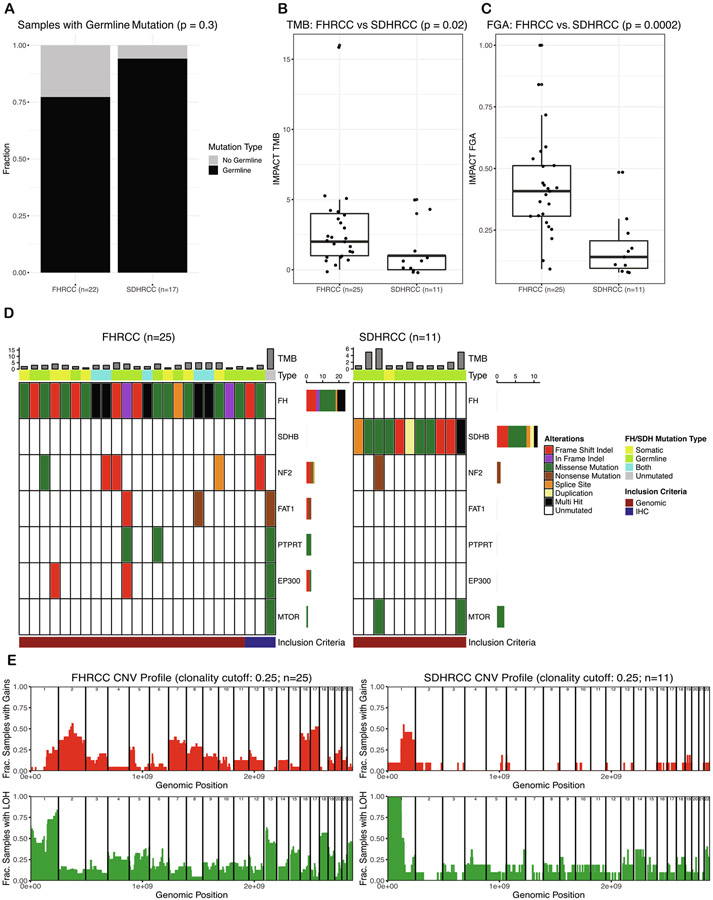

Fig. 1 –

Genomic analysis and comparison of FHRCC and SDHRCC. (A) Comparison of the incidence of germline mutations in the FHRCC and SDHRCC cohorts. SDHRCC tumors are more likely to harbor pathogenic germline variants. Only 22/25 patients with FHRCC consented to germline mutation analysis. (B) FHRCC tumors have a higher tumor mutational burden and (C) fraction of the genome altered. (D) Oncoprint displaying recurrent (genes mutated in ≥3 patients) somatic mutations in FHRCC and SDHRCC tumors. Within the oncoprint, 2/11 SDHRCC and 10/25 FHRCC samples had recurrent mutations. However, 5/11 SDHRCC (45%) and 21/25 (84%) FHRCC samples exhibited a mutation when evaluating any occurrence of at least one somatic mutation. (E) Copy-number profiles for FHRCC and SDHRCC. The top panels indicate the fraction of samples with gains. The bottom panel indicates the fraction of samples with LOH (including copy-neutral LOH). SDHRCC demonstrates universal LOH on chromosome 1p, whereas FHRCC often demonstrates LOH on chromosome 1q. RCC = renal cell carcinoma; FHRCC = FH-deficient RCC; SDHRCC = SDH-deficient RCC; LOH = loss of heterozygosity; TMB = tumor mutational burden; FGA = fraction of the genome altered; IHC = immunohistochemistry; CNA = copy number alteration; Frac. = fraction.