Abstract

Background:

Prevention of the incidences of mental disorders, psychological problems, or their rapid diagnosis is an important issue that has led to the creation of a mental health literacy concept and the development of standard tools for evaluating them. This study is the first step in the designing and psychometrics of the Mental Health Literacy Questionnaire (MHLQ) in Iran. The purpose of this study was to design the psychometric properties of the MHLQ in soldiers.

Methods:

This study is a methodological study that was designed in three phases: 1) Designing the instrument, 2) Assessing the items, and 3) Psychometric assessment. This study was conducted during 2017-2018, and the soldiers were selected by using a convenience sampling method from different garrisons of Tehran, Iran. To evaluate the content validity of the questionnaire 10 experts, to evaluate the face validity 9 soldiers, and for the pilot study 103 soldiers formed the sample size. Finally, construct validity was assessed among 251 soldiers.

Results:

In the first phase, 78 items were collected and designed. Then, based on the experts’ opinions and preliminary studies, the items were reduced to 52 in the “Assessing the items phase” and then to 42 items in the psychometric phase. In the third phase, 31 items remained in the final version. The CVR and CVI scores of the 52 items were 0.91 and 0.94, respectively. Exploratory factor analysis revealed a 4-factor structure with 31 items of special value that were higher than five that accounted for 55.04 of the total scale variance. The fit indices values indicated that the model is fit for the data. In the total scale, the test–retest reliability and Cronbach's alpha were 0.81 and 0.76, respectively.

Conclusion:

The MHLQ of soldiers has appropriate psychometric properties and can be considered as a suitable tool for evaluation and screening as well as a basis for educational and research interventions.

Keywords: Literacy, mental health, military, psychometrics

Introduction

Compared to the efforts made to increase the public's knowledge on physical diseases, significantly less attention has been paid to increase the general awareness of mental disorders in the society. Therefore, mental health awareness should be promoted because it can protect people against mental disorders, improve their mental health, and reduce their medical expenses. Mental Health Literacy (MHL) is a concept that has emerged based on these goals.[1] MHL is a term introduced by Jorm et al.[2] (1977). They defined it as “the awareness and beliefs that enable people to diagnose, manage, or prevent mental disorders”.

Prevention is a key point in MHL that is considered as the most important factor in self-management of symptoms.[1] Prevention is a concept that makes MHL relevant in the military context. Health literacy among the military forces warrants special attention. The extent and diversity of the services provided by the military personnel can make them vulnerable to different health problems including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),[3] suicide,[4] depression,[5] and so on. Research on MHL in the military domain is relatively new in other countries and no study in Iran has focused on this topic so far.

Some studies in different countries have examined some of the MHL components separately and several instruments have been designed to assess these components in general and clinical populations.[6,7,8,9,10] In addition, different studies have considered different components for MHL and have focused on reporting and explaining different MHL components.[1,11,12] In Iran, the validated instruments in this domain can only assess health literacy,[13,14] and there is no instrument assessing MHL among the military populations. The need to develop a comprehensive instrument covering most of the MHL components, being compatible with the Iranian culture and based on the perspectives of the military personnel themselves, motivated us to develop a psychometric assessment of the Mental Health Literacy Questionnaire (MHLQ) and to test it among the soldiers in Tehran.

Methods

Conceptual framework

The present study was conducted in 2017-2018. The sampling method in this study was convenience sampling and the sample size in different stages of the study was determined based on the required information. To evaluate the content validity of the questionnaire 10 experts, to evaluate the face validity 9 soldiers, and for the pilot study 103 soldiers formed the sample size. About 251 people participated in the factor analysis stage. Sample size in the factor analysis stage was determined. According to Comrey and Lee, this was a suitable sample.[15] Inclusion criteria included more than 2 months of service, literacy, informed consent, and exclusion criteria included defects in completing the questionnaires.

This study is based on the conceptual model of MHL proposed by Jorm et al.[2] In this conceptual model, MHL involves seven components, including: 1) The ability to diagnose mental disorders and different kinds of psychological problems, 2) The Knowledge of the risk factors, 3) The Knowledge and beliefs about the causes of mental disorders, 4) The Knowledge and beliefs about available psychiatric interventions and psychotherapies, 5) The Knowledge and beliefs about suicide, 6) The Attitudes that facilitate the diagnosis of mental disorders and help-seeking, and 7) The Knowledge on how to seek mental health information.[2]

Study design

Phase 1: Designing the instrument

Literature review

In this step, in order to identify concepts related to health literacy, a comprehensive literature review about MHL and their components was made in different databases including PubMed, ISI, Science direct, Scopus, and Google Scholar.

Item development

Based on the results of the collected questionnaires,[11,12,16,17,18,19] the identified concepts, and the results of the literature review, a total of 78 items were gathered to assess four components of MHL.

Phase 2: Assessing the Items

Content validity

The CVR and CVI statistics were used for quantitative examination of content validity by using 10 healthcare professionals.[20] Likewise, we interviewed 9 soldiers for ambiguous complex items. According to the Lawshe's table and the experts’ judgment (n = 10), every item with a CVR <0.62 and based on Waltz and Bausell, a CVI <0.79 was excluded from the questionnaire.[20,21]

Pilot study

In order to select proper questions and exclude low-quality questions before conducting the factor analysis, a total of 103 soldiers participated in a pilot study. An item analysis was conducted by analyzing item-total correlation, kurtosis, skewness, and Cronbach's alpha if the item was deleted.

Phase 3: Psychometric

Construct validity

Construct validity was assessed among 251 soldiers between the ages of 23 and 26 years. This examination was conducted in 2018, and the participants were selected by using a convenience sampling method from different garrisons. In the Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), Varimax rotation was used to analyze the data.

In Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), different fit indices were used to assess model fit such as x2/degrees of freedom, Root-Mean-Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Non-Normed Fit Index (NNFI), and Standard Root-Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

Reliability

Cronbach's alpha was used to examine the inter-item correlations in each component and to assess the internal consistency of each component and the total questionnaire. Additionally, the test–retest reliability coefficient was assessed among 25 soldiers over a 2-week interval.

Results

The findings from a study consisting of 251 soldiers also showed that the mean age of the participants was 24.05 (SD = 2.86), and their other characteristics consist of being from a middle economic status (51%), obtaining a bachelor's Degree (39.44%), technical field of study (59.09%), being single (91.63%), their length of service in the military was between 8 and 12 months (35.85%), and only 15 soldiers (5.98%) had a history of mental disorders.

Phase 1: Designing the questionnaire

Operational definitions for the MHL concepts were developed based on seven MHL components; this continued in the form of an iterative process until an agreement was reached by the expert panel. After examining the provided feedback, the seven components were reduced to four [Table 1]. Based on the mentioned concepts and the ideas of the research team, the items were developed. A different rationale was behind designing each item.

Table 1.

Operational definition for MHLQ

| Components | Operational definition | Items |

|---|---|---|

| The ability to diagnose mental disorders | The ability to diagnose mental disorders or the classification of mental disorders in the ICD-10 or DSM-5 | 17 |

| The knowledge on the causes of mental disorders | The knowledge on the psychological, environmental, and genetic factors underlying the development of mental disorders. | 12 |

| The attitude toward mental disorders | An attitude toward mental disorders that hinders or facilitates the process of seeking help. | 15 |

| The knowledge on mental health-promoting activities and resources | The awareness of the centers providing mental health services, mental health professionals, and diagnostic and treatment methods | 34 |

Phase 2: Assessing the items

In the first phase of the study, a total of 78 items were developed. In order to examine the face validity, the questionnaire was administered to 10 experts; only one item was unclear for the them and was modified accordingly. The CVR and CVI values and also the qualitative examination of content validity led to the exclusion of 26 items among the original 78 items, therefore, a total of 52 items were maintained. The entire questionnaire had a CVR of 0.91 and a CVI of 0.94, which confirmed its content validity.

In this stage of the study, the primary analysis of the results was conducted with 103 soldiers who were selected by using a convenience sampling method and were performing their military service in Tehran. Most of the participants were between the ages of 23 and 26 years (53%), had a bachelor's degree (43.7%), had a moderate financial status (58.3), were educated in the technical field (66.0%), were single (94.2%), and had 8–12 months of military service (97.13%). Before analyzing the items, the conformity of the input data with the questionnaire and the conformity of the data with the coding method were examined, and the missing data were addressed. Then the item analysis was performed on the data of the total sample in the pilot study. The results of this analysis and also the feedback from the research team led to the exclusion of 10 items among the 52 items. Finally, the MHLQ with 42 items (four items assessing the ability to diagnose mental disorders, eight items assessing the attitude toward mental disorders, 12 items assessing the knowledge on the causes of mental disorders, and 18 items assessing the knowledge on mental health-promoting activities and resources) was developed for the standardization stage.

Phase 3: Psychometric

In this stage, a total of 277 questionnaires were collected from the participants. Among these, 26 questionnaires were not qualified for the analysis. Before conducting the factor analysis, the item-total correlation, Cronbach's alpha of the deleted items and kurtosis, skewness were calculated to develop proper items and exclude poor items. This led to the exclusion of 42 items; therefore, 33 items were maintained for the factor analysis.

The results from this analysis were obtained by limiting the number of factors to four and setting a minimum factor loading of 0.35 for each item. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) was 0.67, and the Bartlett's Test of Sphericity was 3886.08 (df = 465) that was significant at P = 0.0005. This finding showed that the necessary assumptions of exploratory factor analysis were met. The results of factor analysis indicated a 4-factor structure with eigenvalues above five that together explained 55.04% of the variance of the total scale; therefore, it was the most appropriate and the simplest structure for the data. According to Mulaik et al.[22] and Nunnally,[23] the minimum acceptable value for this index is 50%, therefore the amount of explained variance seems to be acceptable in the first step of developing such a questionnaire [Table 2].

Table 2.

Factors and eigenvalues from the factor analysis of the MHLQ (n=251)

| Factors | Eigen value | Percentage of the variance explained | Cumulative percentage of the variance explained |

|---|---|---|---|

| First | 6.97 | 19.37 | 19.37 |

| Second | 6.11 | 17.03 | 36.40 |

| Third | 5.96 | 16.56 | 52.96 |

| Fourth | 5.63 | 2.08 | 55.04 |

The results showed that among the 33 items that were included in the PCA, two items from the fourth component with factor loadings below 0.35 were excluded. Among the remaining 31 items, four items in the first component, six items in the second component, eight items in the third component, and 13 items in the fourth component had good factor loadings. The analysis of the contents of the items in the four components indicated that all components have the ability to diagnose mental disorders, attitude toward mental disorders, knowledge on the causes of mental disorders, and knowledge on mental health-promoting activities and resources, respectively. [Table 3].

Table 3.

Factors extracted from exploratory factor analysis (varimax rotation) of the MHLQ (n=251)

| First factor | Second factor | Third factor | Fourth factor | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Number of items | Factor loading | Number of items | Factor loading | Number of items | Factor loading | Number of items | Factor loading |

| 1 | 0.52 | 14 | 0.48 | 21 | 0.63 | 33 | 0.29 |

| 2 | 0.47 | 15 | 0.63 | 22 | 0.48 | 34 | 0.47 |

| 3 | 0.54 | 17 | 0.49 | 23 | 0.38 | 35 | 0.73 |

| 4 | 0.63 | 18 | 0.55 | 24 | 0.39 | 36 | 0.56 |

| 19 | 0.64 | 25 | 0.64 | 37 | 0.31 | ||

| 20 | 0.39 | 27 | 0.55 | 39 | 0.52 | ||

| 28 | 0.66 | 40 | 0.73 | ||||

| 29 | 0.59 | 41 | 0.50 | ||||

| 44 | 0.45 | ||||||

| 45 | 0.49 | ||||||

| 46 | 0.83 | ||||||

| 47 | 0.70 | ||||||

| 49 | 0.67 | ||||||

| 50 | 0.65 | ||||||

| 53 | 0.56 | ||||||

The contents of the items were assessed by examining their validity and also by trying to answer the question of whether the items loaded onto the four factors were representing the respective constructs in each subscale. The findings showed that the items were loaded on their respective factors. In the next step, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was performed on the data to examine the construct validity of the questionnaire.

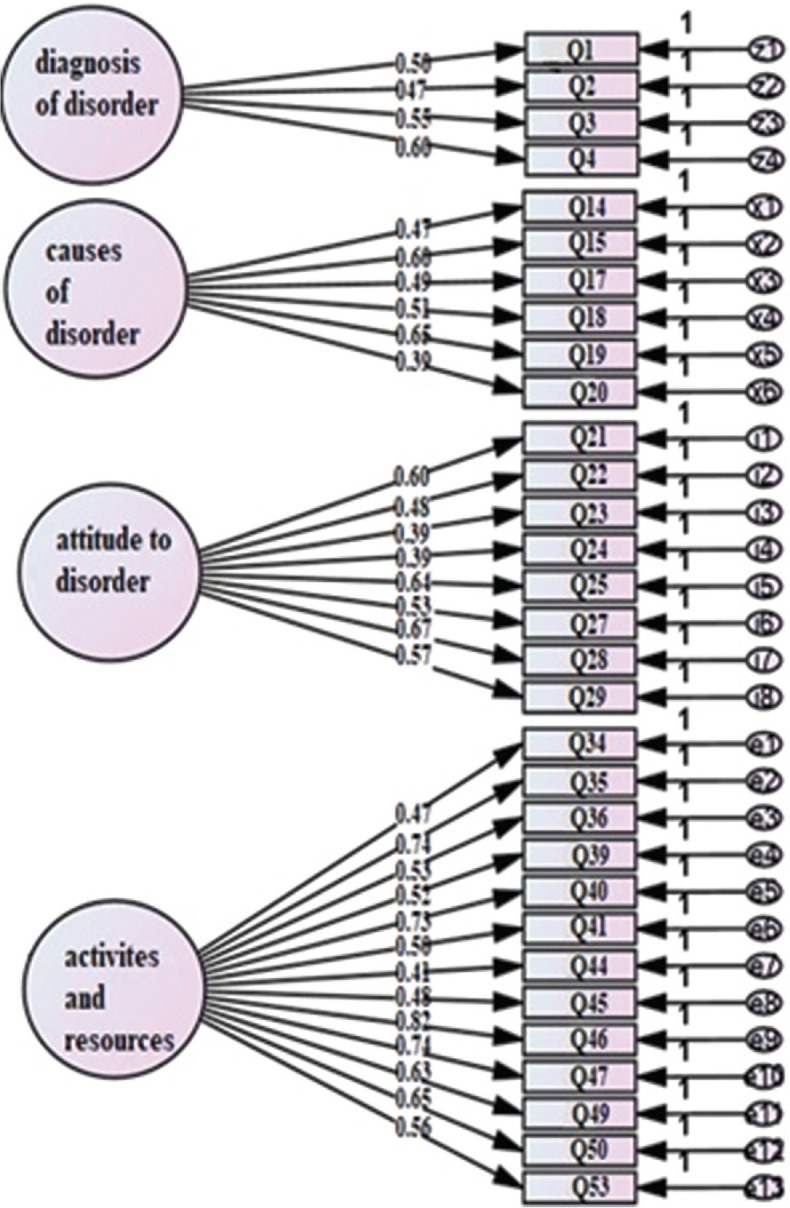

According to Figure 1 and footnote information, the model has good characteristics. Therefore, based on theoretical principles and according to psychometrics, the 4-factor structure of the model is a good fit for the data. In terms of the obtained value for the Chi-square statistic and its significance level, it should be noted that the χ2 value is significant for the model, whereas a proper model should have a nonsignificant χ2 value.[24] According to statisticians in the North Carolina State University,[25] for several reasons including the sample size, violation of the multivariate normality assumption, and the saturation level of the model, judgment about the goodness of fit of the model that was merely based on the χ2 value can be misleading. Therefore, the Chi-square value is traditionally mentioned in the reports, but its significance is not usually considered important.[26] However, lower χ2 values can indicate the goodness of fit of the proposed model.[27] The following acceptable ratios have been proposed for the fit indices: Comparative fit index (at least 0.90), nonnormed fit index (0.05-0.08), root mean square error of approximation (0.06-0.10), and standardized root mean square residual (0.05-0.08). In the present study, the mentioned fit indices were found to be 0.96, 0.96, 0.09, and 0.07, respectively; these values indicated that the model is fit for the data.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis and factor loadings construct validity study for MHLQ1 1χ2 Chi-square value; 89014. df Degree of Freedom; 428. CMIN/df Normed Chi-square test; 2.079. p P value (Chi-square), GFI Goodness of Fit Index; 0.95. CFI Comparative fit index; 0.96. NNFI Non-normed fit index; 0.96. RSMEA Root Mean Squared Error Approximation, CI confidence interval; 0.10, 0.09. SRMR Standard root-mean square residual; 0.07

The descriptive characteristics, item-total correlations, and homogeneity of the subscales were examined. The assess of the reliability of the items, the subscales, and the total scale indicated that all of the subscales had a good homogeneity [Table 4, Fig. 1].

Table 4.

Descriptive characteristics of the items and subscales of the MHLQ (n=251)

| Factors | Items | Mean | SD | α if item deleted | Cronbach alpha | Item-total correlation | Test-retest reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. The ability to diagnose mental disorders | 1 | 2.41 | 0.61 | 0.71 | 0.72 | 0.53 | 0.82 | 0.83 |

| 2 | 1.95 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 0.50 | 0.79 | |||

| 3 | 2.14 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.80 | |||

| 4 | 1.66 | 0.96 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.85 | |||

| 2. The attitude toward mental disorders | 14 | 3.59 | 0.61 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.52 | 0.80 | 0.83 |

| 15 | 2.69 | 1.17 | 0.70 | 0.60 | 0.77 | |||

| 17 | 2.87 | 1.17 | 0.72 | 0.55 | 0.79 | |||

| 18 | 2.45 | 1.34 | 0.71 | 0.58 | 0.81 | |||

| 19 | 2 | 1.47 | 0.70 | 0.63 | 0.87 | |||

| 20 | 3.68 | 0.56 | 0.72 | 0.49 | 0.74 | |||

| 3. The knowledge on the causes of mental disorders | 21 | 2.77 | 1.01 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.81 | 0.82 |

| 22 | 3.33 | 0.65 | 0.74 | 0.51 | 0.83 | |||

| 23 | 2.88 | 1.05 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.81 | |||

| 24 | 2.78 | 0.88 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.79 | |||

| 25 | 3.45 | 0.68 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 0.81 | |||

| 27 | 1.89 | 1.43 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.82 | |||

| 28 | 2.04 | 1.41 | 0.72 | 0.71 | 0.84 | |||

| 29 | 2.15 | 1.16 | 0.73 | 0.64 | 0.78 | |||

| 4. The knowledge on mental health-promoting activities and resources | 34 | 2.61 | 1.30 | 0.81 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.81 | 0.80 |

| 35 | 1.16 | 1.16 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.82 | |||

| 36 | 1.98 | 1.45 | 0.81 | 0.63 | 0.83 | |||

| 39 | 2.52 | 1.38 | 0.81 | 0.50 | 0.82 | |||

| 40 | 2.69 | 1.32 | 0.79 | 0.69 | 0.80 | |||

| 41 | 2.68 | 1.37 | 0.81 | 0.53 | 0.79 | |||

| 44 | 1.49 | 0.84 | 0.81 | 049 | 0.82 | |||

| 45 | 1.33 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 0.54 | 0.81 | |||

| 46 | 0.96 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.85 | |||

| 47 | 1.57 | 0.76 | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.80 | |||

| 49 | 1.28 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.83 | |||

| 50 | 1.51 | 1.30 | 0.80 | 0.67 | 0.82 | |||

| 53 | 2.15 | 1.33 | 0.81 | 0.64 | 0.77 | |||

| Total mean | 0.76 | 0.81 | ||||||

According to the results presented in Table 4, no significant difference is observed even when one of the items is deleted. In other words, the homogeneity of the items is not increased by the removal of the items. Cronbach's alpha coefficients of 0.72, 0.72, 0.74, and 0.81 (0.76 in total), and test–retest reliability of 0.82, 0.80, 0.81, and 0.81 (0.81 in total) were obtained based on their ability to diagnose mental disorders, the attitude toward mental disorders, the knowledge on the causes of mental disorders, the knowledge on mental health-promoting activities, resources and totals, respectively.

Discussion

This was the first study in Iran to be aimed at validating the MHLQ among soldiers. The result showed that CVI and CVR were higher than 0.90, which indicates that the MHLQ can measure MHL in the soldiers.

The MHLQ is different from its counterparts that were validated in other countries: First of all, some of the other instruments only assess one or two components of MHL,[6,9,28,29] whereas the items of this instrument were designed to cover most of the MHL components. Second, this version of the MHLQ seems to be better than that of Jorm et al.[1] in terms of administration time and the scoring difficulty. Third, there is a visible difference between this version and the version developed by O’Connor et al.[12] They used a sample consisting of psychology students to assess the psychometric properties of the MHLQ, whereas the concept of MHL is more focused on increasing general rather than specialized knowledge. Therefore, the psychology students’ previous knowledge could have challenged the concept of MHL.

In the present study, Cronbach's alpha and a test–retest reliability were found to be 0.76 and 0.81, respectively, which showed the reliability and consistency of the scale. Similar to this study, O’Connor et al.'s alpha reported 0.79.[12] The test–retest coefficient for the 10-item version of Mental Health-Promoting Knowledge Measure (MHPK) in Norwegian adolescents was r = 0.74,[30] which was suitable. Cronbach's alpha of the 29-item MHLQ in young adults was 0.84.[31] This difference in reliability indicators can be due to the number of questions, its structure, and the sample size.

The results show that the 4-factor structure of MHLQ explained 55.04% of the variance of the total scale and has favorable fit indexes. It can be concluded that the questions selected in MHLQ to assess the factors are appropriate. In designing the MHLQ, we tried to maintain the Jorm et al.'s[1,2] conceptual framework and to overcome some of the problems in the other versions.

As you can see in the demographic description of the participants, about 57% had a bachelor's degree or higher; therefore, they may have had relatively similar levels of MHL, but had different MHLQ levels. In future studies, it is suggested to consider the demographic variables such as age, education, and so on.

One of the difficulties in assessing MHL stems from the wide range of mental disorders, psychotherapies, and psychiatric interventions is the attitude toward mental disorders and the wide range of resources to improve mental health. For example, there are about 22 categories of mental disorders in DSM-5 and each category consists of several different disorders. We tried to select the most common disorders and the most prominent symptoms, so that people can answer the questionnaire items by using their general knowledge. Future studies in Iran should focus on designing an instrument that allows the assessment of the respondents’ knowledge of 22 categories of mental disorders (separately). In addition, different organizations, especially the public media, should design an effective plan to improve the public's MHL.

The limitations of this study consist of: This study is limited to soldiers and do not include the general population. The generalization of the results cannot be in the general population and that we used the same sample in both the explanatory and confirmatory stages.

Conclusions

The 31-item-MHLQ that was validated among Iranian soldiers allows psychologists and education professionals to design training interventions aimed at improving MHL among young soldiers. Our sample included soldiers and not the formal military personnel; therefore, focusing on military personnel and further examination of the validity and reliability of the questionnaire and also performing cross-sectional studies can help in furthering the knowledge in this domain.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Health Research Center, Lifestyle Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the total participated soldiers.

Reference

- 1.Jorm A. Mental health literacy.public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:317–27. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.5.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jorm AF, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Christensen H, Rodgers B, Pollitt P. ’Mental health literacy’: A survey of the public's ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Med J Aust. 1997;166:182–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin CR, Preedy VR, Patel VB, editors. Comprehensiveguide to post-traumatic stress disorders. Springer International Publishing. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan CJ, Butner JE, Sinclair S, Bryan AB, Hesse CM, Rose AE. Predictors of emerging suicide death among military personnel on social media networks. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2018;48:413–30. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, Segal JB, Peluso MJ, Guille C, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:2214–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF, Evans K, Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive–behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;185:342–9. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kronmüller K-T, Saha R, Kratz B, Karr M, Hunt A, Mundt C, et al. Reliability and validity of the knowledge about depression and mania inventory. Psychopathology. 2008;4:69–76. doi: 10.1159/000111550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler E-M, Agines S, Bowen CE. Attitudes towards seeking mental health services among older adults: Personal and contextual correlates. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19:182–91. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.920300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serra M, Lai A, Buizza C, Pioli R, Preti A, Masala C, et al. Beliefs and attitudes among Italian high school students toward people with severe mental disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2013;201:311–8. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318288e27f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madianos M, Economou M, Peppou LE, Kallergis G, Rogakou E, Alevizopoulos G. Measuring public attitudes to severe mental illness in Greece: Development of a new scale. Eur J Psychiatry. 2012;26:55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, He Y, Jiang Q, Cai J, Wang W, Zeng Q, et al. Mental health literacy among residents in Shanghai. Shanghai Arch Psychiatry. 2013;25:224–35. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1002-0829.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Connor M, Casey L. The Mental health literacy scale (MHLS): A new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiatry Res. 2015;229:511–6. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ghanbari S, Ramezankhani A, Montazeri A, Mehrabi Y. Health literacy measure for adolescents (HELMA): Development and psychometric properties. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149202. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montazeri A, Tavousi M, Rakhshani F, Azin SA, Jahangiri K, Ebadi M, et al. Health literacy for Iranian adults (HELIA): Development and psychometric properties. Payesh. 2014;13:589–99. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Comrey AL, Lee HB. A First Course in Factor Analysis. Psychology Press. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Swami V, Persaud R, Furnham A. The recognition of mental health disorders and its association with psychiatric scepticism, knowledge of psychiatry, and the Big Five personality factors: An investigation using the overclaiming technique. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:181–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0193-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crabb J, Stewart RC, Kokota D, Masson N, Chabunya S, Krishnadas R. Attitudes towards mental illness in Malawi: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:541. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mahfouz MS, Aqeeli A, Makeen AM, Hakami RM, Najmi HH, Mobarki AT, et al. Mental health literacy among undergraduate students of a Saudi tertiary institution: A cross-sectional study. Ment Illn. 2016;8:35–9. doi: 10.4081/mi.2016.6806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furnham A, Gee M, Weis L. Knowledge of mental illnesses: Two studies using a new test. Psychiatry Res. 2016;244:363–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.06.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity 1. Pers Psychol. 1975;28:563–75. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing Research: Design Statistics and Computer Analysis. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mulaik SA, James LR, Van Alstine J, Bennett N, Lind S, Stilwell CD. Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychol Bull. 1989;105:430. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunnally JC, Bernstein I. Psychometric Theory (McGraw-HillSeries in Psychology) Vol. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barrett P. Structural equation modelling: Adjudging model fit. Pers Individ Differ. 2007;42:815–24. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghasemi V. Structural equation modeling in social researchesusing Amos graphics"|Persian} First Edition. Tehran: JameeshenasanPublication; socialists, press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Structural Equation Modelling: Guidelines for Determining Model Fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods, 2008:653–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wheaton B, Muthen B, Alwin DF, Summers GF. Assessing reliability and stability in panel models. Sociol Methodol. 1977;8:84–136. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ascher-Svanum H. Development and validation of a measure of patients’ knowledge about schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50:561–3. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.4.561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hepperlen T, Clay D, Henly G, Barke C, Hehperlen TM, Clay DL. Measuring teacher attitudes and expectations toward students with ADHD.Development of the test of knowledge about ADHD (KADD) J Atten Disord. 2002;5:133–42. doi: 10.1177/108705470200500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.sBjørnsen HN, Ringdal R, Espnes GA, Moksnes UK. Positive mental health literacy. development and validation of a measure among Norwegian adolescents. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:717. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4733-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dias P, Campos L, Almeida H, Palha F. Mental health literacy in young adults: Adaptation and psychometric properties of the mental health literacy questionnaire. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:1318. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]