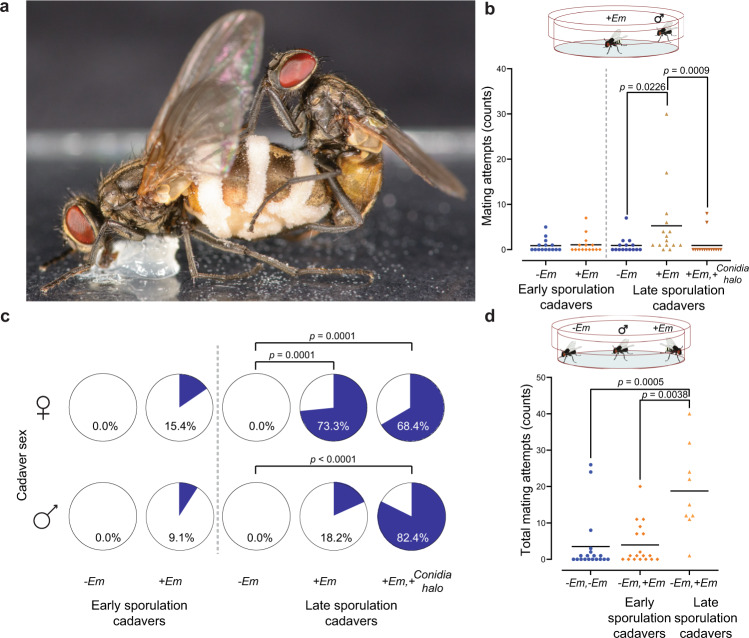

Fig. 1. Male house fly mating attempts towards E. muscae infected cadavers.

a Healthy male house fly attempting to mate with E. muscae sporulating cadaver. Fungal growth is seen as white bands (conidiophores with conidia) extruding from the abdomen of the dead female. The actively discharged conidia are covering large parts of the wings and body of the female cadaver and also create a halo of conidia around the cadaver (Photo: Filippo Castelucci). b Male mating activity towards uninfected freeze-killed (−Em) or infected (+Em) E. muscae-killed cadavers in early (3–8 h post death) and late (25–30 h post death) sporulation stages. Individual data points are shown differentiated by colour and shape and black centrality line depicts the mean (n = 15 per treatment). c Male houseflies used in mating activity experiments towards female cadavers (Fig. 1b) or male cadavers (Supp. Fig. 4), were assessed for successful E. muscae infection. Significant differences using Fisher’s exact test are shown (n = 11–17 flies per treatment). d Mate choice experiment showing total mating attempts towards both cadavers when given a choice between two female cadavers that both were either uninfected (−Em, −Em), one uninfected and one infected in early sporulation stage (−Em, +Em), or one uninfected and one infected at late sporulation stage (−Em, +Em) (n = 19 per treatment, except n = 9 for −Em,+Em late sporulation cadavers). Horizontal black lines show the mean.