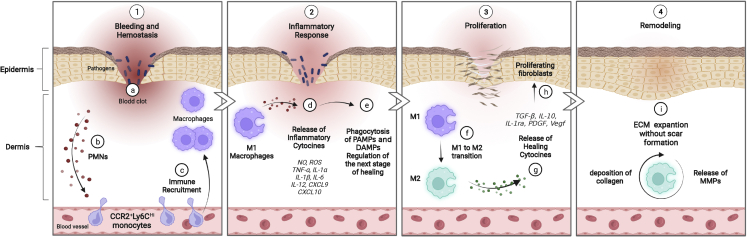

Figure 1.

The role of macrophage cells in wound healing processes

(1) a–c: hemostasis phase. An initial influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) in the blood clot is followed by successive waves of infiltrating monocytes that differentiate into macrophages in the wound. Infiltration of immune cells characterizes the beginning of the inflammatory phase. (2) d and e: during this phase, the differentiated M1 macrophages clear pathogens and cell debris, like pathogen-associated modifying proteins (PAMPs) and damage-associated modifying proteins (DAMPs), and release nitric oxide (NO), reactive oxygen species (ROS), and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1α (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, CXCL9, and CXCL10, to prepare the wound bed for the next stage. (3) f–h: during the proliferation phase, the macrophage phenotype changes from an inflammatory to a healing state, releasing healing cytokines, such as transforming growth factor β (TGF-β), IL-10, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (Vegf). Proliferation, differentiation, and migration of keratinocytes, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells also take place. (4) i: the remodeling phase is the last stage of wound healing, in which macrophages still play a key role by releasing matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to the deposited ECM to restore tissue strength with minimal scar formation. Created with BioRender.