Abstract

Background

Uncertainty is common and impacts both patients and clinicians. The approach to uncertainty in medical trainees may be distinct from that of practicing clinicians and has important implications for medical education.

Objective

Describe trainee approach to uncertainty with the use of chart-stimulated recall (CSR)–based interviews, as well as the utility of such interviews in promoting reflection about decision-making among senior internal medicine (IM) residents.

Design

Qualitative analysis of CSR-based interviews with IM residents.

Participants

Senior IM residents rotating on inpatient night float at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center from February to September 2019.

Intervention

Each participant completed one, 20-min CSR session based on a self-selected case in which there was uncertainty in decision-making. Interviews explored the sources of, approaches to, and feelings about uncertainty.

Approach

Two independent coders developed a codebook and independently coded all transcripts. Transcripts were then analyzed using thematic analysis.

Key Results

The perceived acuity of the patient presentation was the main driver of the approach to and stress related to uncertainty. Perceived level of responsibility in resolving uncertainty during the overnight shift also varied among individual participants. Attending expression of uncertainty provided comfort to residents and alleviated stress related to uncertainty. Residents felt comfortable discussing their uncertainty and felt that the opportunity to think aloud during the exercise was valuable.

Conclusions

Our study demonstrated a novel approach to the exploration of uncertainty in medical decision-making, with the use of CSR. Variations in resident perceived level of responsibility in resolving uncertainty during the overnight shift suggest a need for curriculum development in approach to uncertainty during night shifts. Though residents often experienced stress related to uncertainty, attending expression of uncertainty was an important mitigator of that stress, emphasizing the important role that the trainee-attending interaction plays in the diagnostic process.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11606-022-07396-6.

KEY WORDS: chart-stimulated recall, uncertainty, decision-making, internal medicine

INTRODUCTION

Uncertainty is inherent to everyday medical practice, impacting both trainees and experienced clinicians1. Many factors contribute to this uncertainty, including limitations in knowledge, complexities of treatment, and variability in patient desires and preferences2,3,4,5. In addition, a variety of personal factors, such as experience, resilience, and clinician age/gender, have been described to influence one’s tolerance of uncertainty6,7,8,9. A trainee’s uncertainty tolerance can also influence patient care—those who are less able to cope with uncertainty may experience decreased empathy and are less willing to disclose their uncertainties to patients10,11,12. Physicians who are less tolerant of uncertainty have higher resource utilization and may ultimately cause more harm to patients13,14,15. Experience with uncertainty can also have a significant impact on trainee emotional well-being, with prior studies noting a negative correlation between stress from uncertainty and resilience as well as a positive correlation between tolerance of uncertainty and psychological well-being7,16,17.

Given the ubiquitous nature of uncertainty and its impact on both patient care and trainee well-being, multiple prior studies have attempted to better understand the sources of this uncertainty, noting that sources often come from lack of knowledge, lack of skills, or unknown patient preferences2,3,4. Prior studies have also noted specific steps that residents take to approach uncertainty, often through a hierarchical process, but do not extensively explore mitigating factors such as systems and patient-level factors that may influence one’s approach or the differences in approach between attending physicians and trainees3,4. They also do not account for possible differences in approach to uncertainty across different work settings with varying degrees of autonomy. Finally, methods used in prior studies were limited by hindsight and recall biases, as some were not performed immediately after the patient case and the written format of others did not allow for probing of medical decisions3,4.

Medical school and residency curricula often focus on specific medical knowledge and clinical reasoning skills and may not explicitly emphasize education regarding the approach to uncertainty, despite the prevalence and implications of uncertainty as noted above. Chart-stimulated recall (CSR) is a method that pairs patient chart review with an oral interview component and has the potential to provide rich information about uncertainty in decision-making based on real-world patient information. This method has been utilized for evaluation of resident performance, provision of feedback, and as a clinical research method but has not been specifically used to explore uncertainty18,19,20,21. CSR can also be used as an educational tool to guide reflection on medical decision-making in cases of uncertainty, a process highlighted in a recent systematic review as carrying promise as an effective method to improve decision-making22.

METHODS

Objective

Based on the existing evidence and gaps in the literature as described, and with a goal of informing educational strategies to cope with uncertainty, we designed a CSR-based exercise to explore sources of, approaches to, and feelings about uncertainty in medical decision-making among senior IM residents admitting new patients at night. We also hoped to harness the potential value of CSR as an educational tool to prompt reflection about decision-making.

Design

We conducted an exploratory qualitative interview study using CSR. This study was approved under expedited status by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Setting and Participants

This study was conducted at a single institution. All post-graduate year 2 and year 3 (PGY-2 and 3)IM residents working on inpatient night float during the study period participated in one CSR-based reflection exercise, which was incorporated as an educational exercise during the rotation. We invited residents to participate in the qualitative research study, which allowed investigators to audio-record, transcribe, and analyze the interviews. A total of 45 residents were eligible to participate over the 6-month study period.

During the night float rotation, residents admit up to six patients per shift and staff all new admissions before midnight with the nighttime attending. Each resident supervises one intern, who has cross-cover responsibilities and may admit up to two patients per shift, with the assistance of the resident. Resident-attending discussions of patients admitted after midnight occur on an as-needed basis.

For the CSR session, interviewers reviewed a de-identified history and physical (H&P) from a patient who was admitted during the evening prior, which was used as a basis to further probe the trainee’s decision-making. Residents were instructed to choose an H&P in which there was some uncertainty in their medical decision-making. Each resident completed one, 20-min CSR session during the course of the night float rotation in private conference rooms either immediately after a night shift or immediately preceding a subsequent night shift (i.e., within 24 h of patient admission). We specifically aimed to conduct the CSR session immediately after a patient’s admission in order to minimize hindsight and recall biases noted in prior studies and to obtain a more accurate representation of a trainee’s thought process that may have been altered had more time passed between the patient’s admission and the interview.

With a goal of achieving thematic saturation, we sought to interview at least 24 residents (12 at each PGY level). All residents were invited to participate via email and consent was obtained in person prior to interview initiation.

Intervention

Two general internal medicine fellows (M. M. and E. Y.) conducted semi-structured interviews utilizing an interview guide and CSR methodology between February and September 2019. The study team attempted to organize interviewer/interviewee pairs by lack of prior supervisor-trainee relationship, but on six occasions, the interviewer and interviewee had previously worked together in a clinical setting. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and de-identified.

We developed our interview guide (Appendix 1) based on prior research on uncertainty, as well as on the study team’s specific questions regarding uncertainty in trainees5,6. Specific areas that were explored included (1) sources of uncertainty; (2) approaches to uncertainty; and (3) feelings about uncertainty; we specifically included approach to uncertainty and feelings about uncertainty as these are less described in the literature than sources of uncertainty. During the month prior to study initiation, we conducted pilot interviews with four PGY-3 IM residents who were not a part of the study population; the interview guide was refined based on pilot feedback, though no substantive changes were required.

Participants also completed a survey to evaluate the perceived educational value of reflection on uncertainty in this venue (Appendix 2 Table 5). Surveys were completed 1–2 weeks after the exercise and participants received a $20 Amazon gift card for completion of both the interview and survey components.

MAIN MEASURES

Qualitative Data Analysis

Two coders (M. M. and J. K.) independently reviewed the initial six transcripts and then met to develop a preliminary codebook. An additional six transcripts were then independently reviewed, and the two coders met again to refine the codes and develop a final codebook.

Study transcripts were initially analyzed using inductive content analysis23. Codes were categorized according to the authors’ key areas of exploration: sources of uncertainty, approaches to uncertainty, and feelings about uncertainty. Following content analysis, a thematic analysis was performed in order to identify themes within each category24. Both coders coded all of the interview transcripts and met to adjudicate all differences. This process was assisted by a qualitative research team at the Center for Research on Health Care (CRHC) at the University of Pittsburgh. Coders used Atlas.ti version 8.4.4 for Mac to assist in their coding.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Survey data (demographic survey and evaluation of reflection exercise survey) were entered into REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure Web-based application in full compliance with HIPAA standards for the collection of study data. Descriptive statistics were reported for questions on the survey using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables.

RESULTS

Forty-one out of 45 (91%) eligible residents chose to participate in the study, though only 39 interviews were transcribed and included in the analysis as two interviews did not meet study criteria (cases were intensive care unit transfers rather than new admissions). See Table 1 for demographic data.

Table 1.

Demographic Data (n=41)

| Participants’ characteristics | n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 30 (2.5) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 23 (56) |

| Level of training | |

| PGY-2 | 20 (49) |

| PGY-3 | 21 (51) |

| Staffed by attending overnight | |

| Yes | 36 (88) |

| Number of admissions overnight | 3.5 (1.5) |

| Anticipated career choice | |

| Fellowship | 29 (71) |

| General internal medicine | 7 (17) |

| Undecided | 5 (12) |

Our content analysis found participant sentiments in three main categories: sources of uncertainty, approaches to uncertainty, and feelings about uncertainty. Thematic analysis within those categories is reported below and described in Tables 2, 3, and 4.

Table 2.

Themes Related to Sources of Uncertainty

| Theme | Supporting quote |

|---|---|

| Uncertainty due to incomplete/conflicting information | |

| Patient history (lack of clarity, discordant information) | “I think there was a component of uncertainty that I wasn’t completely confident that I was getting an accurate history from her….it was good to have a trained interpreter with her, but still…I was relying on someone else to provide a history there” |

| Another provider (emergency department, outside hospital, attending, consultant) | “…There’s a lot of uncertainty present from the fact that I didn’t have much prior data, she had never have been in our system before, inpatient or outpatient. They sent very sporadic records with her, so it was a little bit tough trying to find out what was new…” |

| Laboratory and/or imaging studies | “There was some confusion as to whether she thought that that chest pain was similar to her past PE…[the ED] took her to the scanner for a CT angiogram of the chest; they mis-timed the bolus, so it was a non-diagnostic study… I couldn’t definitively say that there was [no PE] because the CT angiogram was mis-bolused…” |

| Diagnostic reasoning uncertainty | |

| Whether to “lump” or “split” patient problems | “I think the uncertainty was kind of a how to lump her complaints or whether to split them all or is there a unifying diagnosis that explains all of this” |

| Presence of severe or “can’t miss” diagnosis | “I thought about things that would fit. And then, I also wanted to make sure that I didn’t miss things that were really bad…so thinking about dangerous things that could cause someone to syncopize” |

| Complex cases/cases that do not fit an illness script | “So part of any syncope workup, there’s like the usual kind of suspects, and for him, there wasn’t really a good, straightforward explanation…his story didn’t necessarily fit perfectly in with vasovagal or an orthostatic…basically, he didn’t fit super well in with any of our typical illness scripts” |

| Management uncertainty | |

| Whether to initiate treatment despite diagnostic uncertainty | “I mean my first concern for her with acute vision loss, with her history was-was this GCA… I was thinking about it for a while about do I give her steroids, do I not give her steroids…” |

| Discussion of risks/benefits of different management options | “Whether to start empiric treatment for HRS was one of our decision points and that I still have a little bit of uncertainty about… it seemed appropriate. I thought the potential benefits outweighed potential risks and there was theoretical benefit to starting overnight and not waiting till the morning” |

Table 3.

Themes Related to Approaches to Uncertainty

| Theme | Supporting quote(s) |

|---|---|

| Acuity of patient presentation (rather than degree of uncertainty) drives approach |

“So diagnostic paracentesis being to rule out SBP as a quite serious possible etiology of her [de]compensation that she was coming in with, needs to be ruled out from the get-go cuz it drastically changes management…” “I knew I didn’t need to get answers to some of them overnight. I didn’t need the answer of why she had cirrhosis urgently…so just sort of accepting that there’s some uncertainty there that we…don’t necessarily need to know the answer to on that time scale.” |

| Perception of the role of night float drives approach to uncertainty (to stabilize acute issues versus to be comprehensive) |

“I think a lot of the things are in [the day team’s] hands. I feel like we set them up, get the story together for them. We can make, you know, kind of emergent decisions, urgent decisions, lay out a plan but at the end of the day, it’s gonna be up to them” “I think the review of systems for her was very important in eliciting what are potential sources [of anemia]…thinking about medications she might be taking, history of bleeding in the past, as well as reviewing family history and then the chart review in terms of looking at old gynecology notes” |

| Use of deliberate diagnostic reasoning to approach uncertainty was common | “So kind of taking two steps back, I thought, really, alcohol withdrawal is what could kill him and so I thought that it was reasonable to just continue with benzos for now, at least for a few more hours so the day team can see him and assess him” |

Table 4.

Themes Related to Feelings About Uncertainty

| Acuity of patient presentation/urgency of situation drove stress about uncertainty more than the degree of uncertainty | “…Initially, I was curious about what was going on, but also simultaneously, I wanted to make sure that the patient didn’t decompensate. And that part kind of…worried me” |

| Discussion with an attending provided comfort, especially when the attending also expressed uncertainty | “Initially [I was] a little bit worried just trying to figure out what I was missing and then when I spoke to my attending and she was just as confused, I [felt] …better about the uncertainty.” |

Sources of Uncertainty

Sources of uncertainty were identified and categorized into three broad themes: (1) uncertainty due to incomplete/conflicting information, (2) diagnostic reasoning uncertainty, and (3) management uncertainty. Some sources occurred early in the clinical reasoning process (data gathering), while others occurred later (development of differential diagnosis); in many cases, multiple sources of uncertainty were identified25.

Approaches to Uncertainty

Overall, resident approaches to uncertainty did not map directly to a specific source of uncertainty but, rather, depended on a variety of patient and trainee-specific factors that are detailed below.

Theme 1:Acuity of patient presentation (rather than degree of uncertainty) drives approach

Residents commonly noted that the acuity of a patient’s presentation (i.e., the stability/instability) drove their approach to uncertainty overnight. This often included whether steps needed to be taken to address uncertainty overnight or whether decision-making could be deferred to the day team. Patient acuity also influenced testing and treatment thresholds, as residents had a lower threshold to both test and treat in more acute patient situations. Consideration of specialty consultation was common, but the decision to call consults overnight was driven more by patient acuity than by degree of uncertainty. Finally, in less acute patient situations, residents often chose to proceed in a step-wise approach or noted that they had time to make additional diagnostic and management decisions.

Theme 2:Residents had varying perceptions of the role of night float, which drove their approach to uncertainty (to just stabilize acute issues versus to be comprehensive)

Overall, we found that varying perceptions of the role of the night float resident was another important driver of resident approach to uncertainty. Some residents viewed their night float role as to stabilize the patient and to address urgent issues overnight, while others viewed their role as to both stabilize and comprehensively evaluate the patient. Those in the latter group were more likely to take diagnostic and management steps to address uncertainty overnight, even in cases where patient acuity did not demand it. Some residents also specifically noted that their decision to be more comprehensive was to assist the day team.

Theme 3:Use of clinical reasoning principles, including consideration of “can’t miss” diagnoses, to approach uncertainty was common

Residents often used specific clinical reasoning principles in their approach, attempting to compare patient presentations to known illness scripts. This included reviewing additional data sources in order to ensure completeness in comparisons to illness scripts and to counter any knowledge deficits. Residents often also considered “can’t miss” diagnoses such as a pulmonary embolism for patients with common presenting complaints, such as dyspnea. This process was described across varying degrees of uncertainty, even when the degree of uncertainty was low.

Feelings About Uncertainty

Theme 1:Acuity of patient presentation/urgency of situation drove stress about uncertainty more than the degree of uncertainty

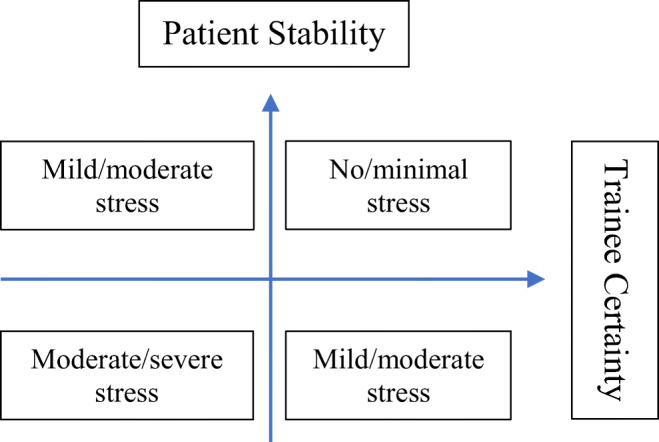

Residents cited patient acuity as the most important driver of stress related to uncertainty during their overnight shifts. If patient acuity was low, residents expressed low stress related to uncertainty, even when the degree of uncertainty or patient complexity was high. If patient acuity was high, however, residents experienced more stress, even when the degree of uncertainty was low. This spectrum of stress related to both the stability of the patient and the uncertainty of the trainee is displayed in Figure 1.

Theme 2:Discussion with an attending provided comfort, especially when the attending also expressed uncertainty

Figure 1.

Stress from uncertainty is related to both trainee uncertainty and patient stability.

Residents cited discussions with the attending physician as an important mitigator of uncertainty-related stress, especially when the attending also expressed uncertainty. The comfort provided in these encounters seemed to stem from the attending role modeling a level of comfort with uncertainty, which then allowed the resident to feel more comfortable.

Evaluation of Educational Value of Exercise

A total of 37 out of 45 eligible residents completed the survey. Participants indicated that the opportunity to reflect aloud about an uncertain patient case was useful (n=22, 60% strongly agree/agree). Many participants felt that additional CSR sessions should include feedback on decision-making (n=25, 68% strongly agree/agree), while some felt that additional sessions should include additional teaching (n=14, 39% strongly agree/agree). Free-text comments included several suggestions for improvement, notably the addition of feedback on decision-making and consideration of optimal timing for the exercise (citing fatigue after a night float shift).

DISCUSSION

In this single-center study of PGY-2 and PGY-3 IM residents, we demonstrated a novel approach to the exploration of uncertainty with the use of CSR. Our use of this methodology in real-time in the clinical setting was the first to specifically describe individual trainee approaches to uncertainty when admitting new patients at night.

In this study, we found that the approach to uncertainty was driven more by patient acuity than by degree of uncertainty. Prior studies have noted that residents often attempt to resolve uncertainty using a hierarchical process, though our study described potential differences in approach based on patient acuity and other situational factors2,4. Patient acuity may cause residents to deviate from the hierarchical process and consult with attendings or other consultants before the use of additional resources. This specific approach may also be more relevant to night float rotation in general, where stabilization of patients and resolution of acute issues may take precedence over the more comprehensive care provided during the day.

Interestingly, we also observed variability in the perception of the role of the night float resident in the diagnostic and management process, with some residents preferring to be comprehensive and others viewing their role as simply to stabilize more acute issues. This describes a form of inter-personal uncertainty rather than intra-personal uncertainty and may relate to lack of specific expectations within residency programs about the role of night float. In addition, lack of comprehensive patient information at night (i.e., outside hospital records, collateral from family, etc.) may cause residents to initially focus on patient stabilization and resolution of acute issues, deferring more comprehensive care to daytime teams. A stabilization-only approach may create additional work for the day team but may mitigate emotional exhaustion on an already busy rotation for night float residents. In addition, though prior studies on the night float rotation have sought to better understand educational opportunities at night and the preference of night float versus 24-h call, less is described in the literature about the specific clinical role of the night float resident26,27,28,29. In fact, though the ACGME mentions some guidance regarding night float, no specific expectations are provided regarding the clinical role of the night float resident. Thus, which view is preferable from both a resident-standpoint and a programmatic standpoint has yet to be determined30.

Our finding that attending role modeling of and reflection about uncertainty provided comfort and alleviated uncertainty-related stress underscores the important role of the supervising attending. Prior studies have identified uncertainty as a source of stress for trainees, both on daytime and night float rotations, and found that a higher level of psychological distress is associated with higher intolerance of uncertainty31,32,33,34. Our findings suggest that attending role modeling of the approach to uncertainty has the potential to positively impact both tolerance of uncertainty and stress related to uncertainty in trainees. Given the previously identified connections between stress from uncertainty and trainee wellness and resilience, further exploration of this relationship is warranted7,16,17.

Our findings also highlight the importance of deliberate consideration of the attending’s role in resident education at night. Though many hospitalist groups have nighttime attending physicians to supervise trainees, only 38% define a formal supervisory or teaching role for the overnight attending35. The variability in approach to uncertainty by our residents, as well as the comfort attending support at night provides, suggests a need to define the exact role of the overnight attending in the trainee educational experience. This is especially true as prior studies have noted that increased overnight supervision through the role of a “nocturnist” enhanced residents’ perceptions of the value of the rotation without a decrease in trainee perception of autonomy36,37,38.

Finally, residents in our study reported that the use of CSR to reflect on their own uncertainty was useful. This is consistent with prior studies that noted the value of structured reflection as an educational exercise, with the important addition that reflection specifically regarding feelings about uncertainty is something residents value and are comfortable with39,40. Participants in our study also suggested that the addition of feedback to the exercise would add value. While our intervention was not designed to provide feedback, others have previously demonstrated pairing of structured reflection with feedback, either as part of a CSR exercise, through completion of a reflection worksheet paired with attending feedback, or through EMR-based feedback from daytime residents21,26,41.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center study with senior IM residents on a night float rotation, and our findings may not be generalizable to a broader group of trainees or to the daytime setting. In addition, our study design included reflection about patient cases without an intervening period of time to allow for clinical evolution and/or receipt of feedback. While this design allowed for minimization of potential recall and hindsight bias, it may also have limited the educational value of reflection when not paired with case follow-up and feedback. Finally, our findings were based on self-report of resident behavior rather than direct observation or other objective measures, though this was mitigated somewhat with the use of residents’ own notes.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study demonstrated a novel approach to the exploration of uncertainty in medical decision-making, with the use of CSR. The variability in the perception of the clinical role of the night float resident has not been previously explored and may warrant both additional research and expectation setting within a residency program. Finally, attending mitigation of stress related to uncertainty emphasizes the importance of role modeling and supervision by the attending, including during more autonomous rotations such as night float.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 24.5 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the clinical research team at the Center for Research on Health Care (CRHC) Data Center at the University of Pittsburgh for its statistical support as well as the UPMC Clinical Center for Medical Decision-Making for project review and guidance.

Funding

This work was supported by the Thomas H. Nimick, Jr. Competitive Research Fund of UPMC Shadyside Hospital and the Shadyside Foundation.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: Diagnostic Error in Medicine Conference in 2020 and the Regional Society of General Internal Medicine Meeting in 2019. Mutter, M., Yecies, E., Kyle, J., and DiNardo, D. Use of Chart-Stimulated Recall to Examine Uncertainty in Decision-Making Among Senior Internal Medicine Residents.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Ghosh AK. Understanding medical uncertainty: a primer for physicians. J Assoc Physicians India. 2004;52:739–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamui-Sutton A, Vives-Varela T, Gutiérrez-Barreto S, Leenen I, Sánchez-Mendiola M. A typology of uncertainty derived from an analysis of critical incidents in medical residents: A mixed methods study. BMC Med Education.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Beresford EB. Uncertainty and the shaping of medical decisions. Hast Cent Rep. 1991;21:6–11. doi: 10.2307/3562993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farnan JM, Johnson JK, Meltzer DO, Humphrey HJ, Arora VM. Resident uncertainty in clinical decision making and impact on patient care: a qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:122–6. 11. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2007.023184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han PK, Klein WM, Arora NK. Varieties of uncertainty in health care: a conceptual taxonomy. Med Decis Mak. 2011;31:828–38. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10393976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Begin AS et al. Factors Associated with Physician Tolerance of Uncertainty: an Observational Study. J Gen Intern Med, 1–7. 2021. 10.1007/s11606-021-06776-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Simpkin AL, Khan A, West DC, Garcia BM, Sectish TC, Spector ND, Landrigan CP. Stress From Uncertainty and Resilience Among Depressed and Burned Out Residents: A Cross-Sectional Study. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(6):698–704. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geller G, Tambor ES, Chase GA, Holtzman NA. Measuring physicians’ tolerance for ambiguity and its relationship to their reported practices regarding genetic testing. Med Care. 1993;31(11):989–1001. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawton R, Robinson O, Harrison R, et al. Are more experienced clinicians better able to tolerate uncertainty and manage risks? A vignette study of doctors in three NHS emergency departments in England. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28:382–388. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerrity MS, DeVellis RF, Earp JA. Physicians’ reactions to uncertainty in patient care: a new measure and new insights. Med Care. 1990;28(8):724–736. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hojat M, Vergare MJ, Maxwell K, et al. The devil is in the third year: a longitudinal study of erosion of empathy in medical school. Acad Med. 2009;84(9):1182–1191. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181b17e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon GH, Joos SK, Byrne J. Physician expressions of uncertainty during patient encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2000;40:50–65. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(99)00069-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz J. Why doctors don't disclose uncertainty. Hast Cent Rep. 1984;14(1):35–44. doi: 10.2307/3560848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allison JJ, Kiefe CI, Cook EF, Gerrity MS, Orav EJ, Centor R. The Association of Physician Attitudes about Uncertainty and Risk Taking with Resource Use in a Medicare HMO. Med Decis Mak. 1998;18(3):320–329. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9801800310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kassirer JP. Our stubborn quest for diagnostic certainty. A cause of excessive testing. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(22):1489–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198906013202211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Strout TD, Hillen M, Gutheil C, et al. Tolerance of uncertainty: A systematic review of health and healthcare-related outcomes. Patient Educ Couns. 2018;101(9):1518–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hancock J, Mattick K. Tolerance of ambiguity and psychological well-being in medical training: A systematic review. Med Educ. 2020;54(2):125–137. doi: 10.1111/medu.14031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Philibert I. Using Chart Review and Chart-Stimulated Recall for Resident Assessment. J Grad Med Educ 2018. 10.4300/JGME-D-17-01010.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Jennett, et al. Patient charts and physician office management decisions: Chart audit and chart stimulated recall. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 1995;15(1):31–39. doi: 10.1002/chp.4750150105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinnott C, Kelly MA, Bradley CP. A scoping review of the potential for chart stimulated recall as a clinical research method. BMC Health Serv Res 2017. 10.1186/s12913-017-2539-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Holt S, Sofair A. Resident and Faculty Perceptions of Chart-Stimulated Recall. South Med J. 2017;110(2):142–146. doi: 10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prakash S, Sladek RM, Schuwirth L. Interventions to improve diagnostic decision making: A systematic review and meta-analysis on reflective strategies. Medical Teacher 2018. 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1497786 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res2005. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- 25.Bowen JL. Educational strategies to promote clinical diagnostic reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(21):2217–25. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim H, Raffel KE, Harrison JD, Kohlwes RJ, Dhaliwal G, Narayana S. Decisions in the Dark: An Educational Intervention to Promote Reflection and Feedback on Night Float Rotations. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(11):3363–3367. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05913-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bricker DA, Markert RJ. Night float teaching and learning: perceptions of residents and faculty. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(2):236–41. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-10-00005.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sun NZ, Gan R, Snell L, Dolmans D. Use of a Night Float System to Comply With Resident Duty Hours Restrictions: Perceptions of Workplace Changes and Their Effects on Professionalism. Acad Med. 2016;91(3):401–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bolster L, Rourke L. The effect of restricting residents' duty hours on patient safety, resident well-being, and resident education: an updated systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(3):349–63. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-14-00612.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Accreditation Council for Graduate medical Educations. Milestones Guidebook for Residents. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2021.pdf. Accessed December 14 2021.

- 31.Nevalainen MK, Mantyranta T, Pitkala KH. Facing uncertainty as a medical student: a qualitative study of their reflective learning diaries and writings on specific themes during the first clinical year. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):218–223. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iannello P, Mottini A, Tirelli S, Riva S, Antonietti A. Ambiguity and uncertainty tolerance, need for cognition, and their association with stress: a study among Italian Kangmoon Kim and Young-Mee Lee : Teaching and understanding of uncertainty in medicine 188 Korean J Med Educ 2018 Sep; 30(3): 181-188. practicing physicians. Med Educ Online. 2017;22(1):1270009. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2016.1270009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lally J, Cantillon P. Uncertainty and ambiguity and their association with psychological distress in medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Çalişkan Tür F, Toker I, Şaşmaz CT, Hacar S, Türe B. Occupational stress experienced by residents and faculty physicians on night shifts. Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Farnan JM, Burger A, Boonyasai RT, et al. SGIM Housestaff Oversight Subcommittee. Survey of overnight academic hospitalist supervision of trainees. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:521–523. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Catalanotti JS, O’Connor AB, Kisielewski M. et al. Barriers to Accessing Nighttime Supervisors: a National Survey of Internal Medicine Residents. J Gen Intern Med. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Haber LA, Lau CY, Sharpe BA, Arora VM, Farnan JM, Ranji SR. Effects of increased overnight supervision on resident education, decision-making, and autonomy. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(8):606–610. doi: 10.1002/jhm.1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Trowbridge RL, Almeder L, Jacquet M, Fairfield KM. The effect of overnight in-house attending coverage on perceptions of care and education on a general medical service. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2:53–56. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-09-00056.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lambe KA, O’Reilly G, Kelly BD, Curristan S. Dual-process cognitive interventions to enhance diagnostic reasoning: A systematic review. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2016 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Croskerry PA. Universal Model of Diagnostic Reasoning. Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1022–1028. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ace703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lane KP, Chia C, Lessing JN, Limes J, Mathews B, Schaefer J, Seltz LB, Turner G, Wheeler B, Wooldridge D, Olson AP. Improving Resident Feedback on Diagnostic Reasoning after Handovers: The LOOP Project. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):622–625. doi: 10.12788/jhm.3262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 24.5 kb)