Abstract

Background

The aim of the study is to observe the ocular manifestation in patients of psoriasis.

Methods

All the diagnosed cases of Psoriasis by the dermatology department of this tertiary care hospital were included in this study. Relevant details of the history pertaining to disease duration, type of psoriasis, and treatment undertaken including ocular symptoms were obtained. Disease severity was quantified using the PASI score. Complete ocular examination including intraocular pressure, Schirmer I and II tests, Tear Film Breakup Tme (TBUT); was carried out for all the patients.

Results

Of 126 patients of psoriasis, ocular manifestations were seen in 76 patients (60.3%). Dry eyes (27%) and blepharitis (15.9%) were the most common ocular manifestations. Uveitis was seen in 3.2% of the patients of which 75% patients were HA B27-positive psoriatic arthritis, which was statistically significant (p = 0.001). There was no statistical correlation between duration of the disease and ocular manifestations (p value is 0.077 using chi square test). The ocular manifestations were more common in patients with PASI score 10 when compared with the patients with PASI score 10 (p value = 0.028) which was statistically significant.

Conclusions

In our study, prevalence of ocular manifestation was 60.3% which increased with the increasing PASI score. Dry eyes and blepharitis were the most common manifestations. Hence, routine ocular examination is recommended in patients with psoriasis.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Ocular manifestations, PASI score, Dry eyes, Blepharitis

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated, inflammatory skin disease which manifests as symmetrically distributed well-defined erythematous scaly plaques over predominantly extensor surfaces. Around 60% of patients of psoriasis complain of pruritus, 80% have scalp involvement and 40% have nail affection. Chronic plaque psoriasis is the commonest form of psoriasis, but in 2–4% of patients, the disease might complicate and result in potentially life-threatening conditions such as erythroderma and pustular psoriasis.1 Psoriasis has a reported prevalence of 2–3% globally and 0.44–2.8% in the North Indian population as per the studies2 with a strong genetic predisposition.

Ocular manifestations are seen in around 50–60% of patients affected with psoriasis.3 However, only limited data are available from the studies based on populations in Europe and the far east.3, 4, 5, 6 Similar knowledge from the Indian population is restricted leading to a dearth of information in the Indian scenario. Systemic associations of psoriasis include psoriatic arthritis, metabolic syndrome, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Psoriatic arthritis is the commonest among all systemic associations which is usually preceded by the classic skin findings and gradually develops over 5–10 years. Psoriatic arthritis is an inflammatory, seronegative, spondyloarthropathy (SpA) that is associated with HLA B27 positivity in 10–25%5,6 and has been reported in up to 30% psoriatic patient and usually manifests as asymmetrical oligoarthritis.7 There is a known association of uveitis and HLA-B27 spondyloarthropathies, including psoriatic arthritis.7,8 The ocular involvement in psoriatic arthritis in the form of uveitis is severe and recurrent.7,8 This is the finding with which most clinicians are familiar because it is a serious ocular manifestation and, if not treated promptly, can lead to irreversible loss of vision.

The commonly seen ocular manifestations in patients of psoriasis are dry eyes and blepharitis.9, 10, 11 Other ocular manifestations encompass pinguecula, punctate keratitis, cataract, uveitis, glaucoma and retinal microvascular abnormalities.12 The ocular symptomatology and manifestations seemingly increase with increased severity of the disease which is recorded by the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score. 2,11 Ocular manifestations in psoriasis being subtle can go unnoticed.11,13

Hence, it may be advisable to carry out regular ocular examinations in patients with psoriasis to facilitate timely diagnosis and treatment of the symptoms and also to prevent the ocular complications. Detailed studies are needed to explore the differences in the ocular manifestations of psoriasis in different genetic and geographical habitats. The aim of the present study is to describe the ocular manifestations in patients of psoriasis in western India. To the best of our knowledge, studies from Indian population are limited.

Materials and methods

An interdisciplinary cross-sectional and observational hospital-based study was conducted, and all the cases of psoriasis clinically and histopathologically diagnosed by the dermatology department of a tertiary care hospital during the period December 2018–January 2020 were included in this study. Ethical clearance was obtained from the institutional ethics committee board before enrolling the patients for the study. Informed written consent was taken from all the patients older than 18 years (from parents in patients aged <18 years).

A detailed account of patient's demographic characteristics including age, gender, duration of disease, type of psoriasis and treatment was taken into consideration. PASI score was calculated to assess the severity of the disease by the dermatologist. All the patients were thoroughly evaluated to observe any ocular manifestation. Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was taken on Snellen's chart at 6 m in a well-lit examination room. Anterior segment examination was performed with a slit lamp under diffuse and direct illumination to examine the ocular structures including the adnexal examination; anterior chamber examination was performed to rule out uveitis; IOP was measured with Goldmann applanation tonometry, Tear Film Breakup time (TBUT); Schirmer-1 and Schirmer-2 tests were performed to detect dry eyes and general fundus examination was performed by 90D Lens using slit lamp biomicroscope or with direct and indirect ophthalmoscope to evaluate macula and peripheral retina. Fundus pictures, Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Fundus Fluorecein Angiography (FFA) were performed when required. Finally, all the findings were documented and analysed.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All clinically and histopathologically diagnosed cases of psoriasis irrespective of duration of disease were included in this study.

The exclusion criteria included patients with pre-existing anterior or posterior segment pathology/prior trauma or those who were diagnosed with diabetes, hypertension and immunosuppressive diseases or the patients who were regularly using contact lens as these can act as the confounding factors in the study.

Statistical analysis of data

Data were collected in a case record form and analysed subsequently using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences) version 22.0. Qualitative data variables were expressed using frequency and percentage. Quantitative data variables were expressed using mean and standard deviation. Chi-square test has been used to find the significance between the occurrence of ocular manifestations in psoriasis with various qualitative data variables. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 126 diagnosed cases of psoriasis were included in this study, out of which 78 (61.9%) were males and 48 (38.1%) were females.

Most patients were in the age group of 41–50 years which comprised 34.9% of the sample size. The mean age was found to be 42.39 ± 2.37 yrs. The ocular manifestations were mostly seen in the patients aged 51 years and older. The correlation was statistically significant (p < 0.001) as per Chi-square test (Graph 1).

Graph 1.

Graph showing number of patients with ocular manifestations in different age groups.

The study group consisted of 92 patients (73.1%) of chronic plaque psoriasis. Guttate psoriasis was seen in 9 patients (7.1%), 8 patients (6.3%) had erythrodermic psoriasis, whereas remaining 5 patients (4%) had pustular psoriasis. The prevalence of chronic plaque psoriasis was much greater than the other types of psoriasis in this study. Psoriatic arthritis was noted in 12 (9.5%) patients associated with psoriasis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Few of the clinical photographs of the different patterns of psoriasis seen in our study population. a) and b) Erythrodermic psoriasis; c) plaque psoriasis; d) pustular psoriasis.

Nineteen out of 126 patients had a BCVA score of less than 6/6 which constituted 15.1% of all the patients. Overall, ocular manifestations were seen in 76 patients (60.3%) out of 126 patients in the study population. In our study, we found an overlap of various ocular manifestations. However, while evaluating the patients of different types of psoriasis, we found out 51 (55.4%) out of 92 patients of chronic plaque psoriasis, 5 (55.6%) out of 9 patients of guttate psoriasis, 7 (87.5%) out of 8 erythrodermic psoriasis patients, 2 (40.0%) out of 5 patients of pustular psoriasis and 11 (91.7%) out of 12 patients of psoriatic arthritis had ocular manifestations. Chi-square test has been used (Significant p value < 0.05) to find out the ocular manifestations in different types of psoriasis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Table showing prevalence of ocular manifestations in different types of psoriasis

| Types of Psoriasis | Ocular Manifestations |

Total | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present | Absent | |||

| Chronic plaque psoriasis | 51 (55.4%) | 41 (44.6%) | 92 | 0.066 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 11 (91.7) | 1 (8.3%) | 12 | 0.020a |

| Guttate psoriasis | 5 (55.6%) | 4 (44.4%) | 9 | 0.959 |

| Erythrodermic psoriasis | 7 (87.5%) | 1 (12.5%) | 8 | 0.211 |

| Pustular psoriasis | 2 (40.0%) | 3 (60.0%) | 5 | 0.356 |

| Total | 76 | 50 | 126 | |

Significant p-value < 0.05 using Chi-square test.

The duration of the disease in the study population ranged from 1 year to 12 years with a mean duration of 4.76 ± 2.36 years. There was no statistical correlation noted between the duration of the disease and presence of ocular manifestations (p = 0.077 by Chi-square test) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of psoriasis patients with or without ocular manifestations based on disease duration

| Duration of Disease | Total no. of Patients | Ocular Manifestations |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||

| ≤5 years | 61 | 31 (50.8%) | 30 (49.2%) | 0.077 |

| 5–10 years | 39 | 23 (59.0%) | 16 (41.0%) | |

| >10 years | 26 | 20 (76.9%) | 6 (23.1%) | |

| Total | 126 | 76 | 50 | |

Fourty patients (31.7%) had a PASI score less than 10, 75 patients (59.5%) had a PASI score in the range of 10–20 and remaining 11 patients (8.7%) had a PASI score more than 20. However, ocular manifestations were more commonly seen in patients with a PASI score >10 when compared with patients with PASI ≤ 10, and this difference was statistically significant (Graph 2).

Graph 2.

Graph showing the number of patients with ocular manifestations depending on the severity of the disease.

Out of 126 patients in the study population, 106 patients were managed with topical treatment only in the form of topical corticosteroids and emollients. On evaluation, 59 out of 106 patients (55.7%) had ocular manifestations. Remaining 20 patients were receiving systemic treatment in the form of tablet methotrexate along with topical steroids and emollients out of which 17 (85%) patients had ocular manifestations. The correlation was statistically significant (p < 0.023) by Chi-square test.

The patients in the study population most commonly presented with the symptom of irritation (26.2%) followed by redness seen in 15.1% patients. Fifteen percent of patients presented with burning sensation and 13% patients had diminished vision, whereas 4% patients presented with pain. Few patients presented with more than one symptomatology, but with meticulous history taking, we tried to differentiate and further categorize the symptoms.

In our study, dry eyes was the most common ocular manifestation observed in 34 patients (27%), followed by blepharitis seen in 20 patients (15.9%). Conjunctival involvement in our study was seen as conjunctivitis in 9 patients (7.1%), pinguecula in 7 patients (5.6%) and pterygium in 6 patients (4.8%). Episcleritis was seen in 5 patients (4%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Ocular manifestations as observed in the study population; a) pterygium; b) conjunctivitis; c) blepharitis; d) episcleritis; e) cataract; f) chronic uveitis with festooned pupil; g) fundus photograph of macular edema; h) macular edema on FFA; i) cystoid macular edema on Optical Coherence Tomography.

None of the patients in this study had corneal involvement in the form of opacity, vascularization or melting. Cataract was seen in 13 patients (10.3%) in the age group of 50–70 years and was probably age related. Our conclusion was based on the fact that all these patients were older than 50 years and no cataract was seen in patients younger than 50 years (Graph 3).

Graph 3.

: Graphical representation of ocular manifestations.

Uveitis was seen in 4 patients (3.2%) out of which 3 patients (75%) had HLA B27–positive psoriatic arthritis, whereas one patient of uveitis (25%) had no correlation with HLA. The association was statistically significant.

Defective vision due to macular edema probably as a complication of uveitis was seen in 3 eyes of 3 patients (3.4%) which was further confirmed on OCT and FFA.

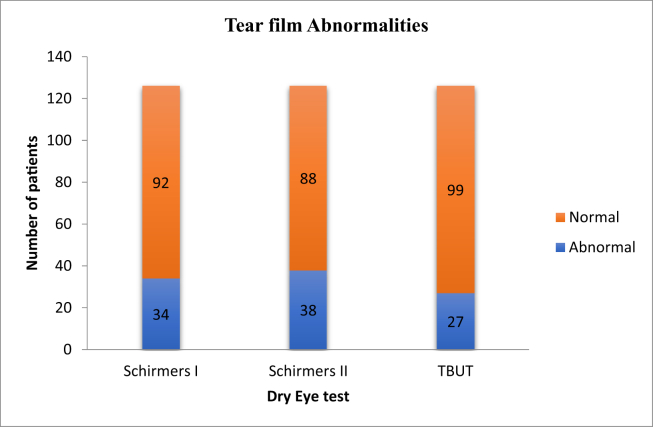

Schirmer-1 test measures the basal and reflex tear secretion. The value of this test was less than 10 mm in 34 patients (27%). Schirmer-2 measures the basal secretion of tears, and the value of less than 5 mm was seen in 38 patients (30.2%). Tear film breakup time was reduced (less than 10 s) in 27 patients (21.4%). Few patients had abnormality in more than 1 test (Graph 4). Thirty-four (26.98%) patients out of a total of 126 patients had an abnormal Schirmer-1 test. Of these, 27 (79.41%) were males and 7 (20.59%) were females. The value was statistically significant (p < 0.022) using Chi-square test. Out of total 78 males who were evaluated in this study, 27 males (34.61%) had abnormal Schirmer-1 test. Similarly, out of 48 females who were evaluated in this study, 7 females (14.5%) had abnormal Schirmer-1 test. As it is an observational study that included a consecutive sampling method, gender bias in result is a drawback. TBUT was reduced in 27 patients in which 19 (70.37%) were males and 8 (29.62%) were females. Intraocular pressure was within the normal range in our study.

Graph 4.

: Graphical distribution of tear film abnormalities in the study population based on the test results.

Discussion

Psoriasis is an inflammatory dermatological condition with several extracutaneous manifestations of which ocular complications are common and affect almost all the ocular structures. In our study, conducted on western Indian population, the overall prevalence of ocular manifestations in psoriasis patients was found to be 60.3%. Similar studies carried out by Chandran et al 3 and Kilic et al 14 had found the prevalence of ocular manifestations in psoriasis to be 67% and 58%, respectively.

Most patients involved in this study were males (61.9%), whereas females constituted 38.1% of the study. The mean age of the patients was 42.39 ± 13.03 years. The ocular manifestations were seen more frequently in patients older than 51 years. However, the prevalence of ocular features was almost similar in both the genders. The findings of the present study were comparable to those of a similar study carried out by Erbagci et al 15 on 235 patients including 76.17% males with age ranging from 19 years to 80 years, and the mean age was 46.18 ± 13.54 years.

The duration of the disease in the study population ranged from 1 year to 12 years with a mean duration of 4.76 ± 2.36 years. There was no statistical correlation noted between the duration of the disease and severity of ocular manifestations (p = 0.077 by Chi-square test). A similar result was seen in the studies carried out by Okamoto et al and Maitray et al who found no correlation between the disease duration and the presence of ocular manifestations.

Most patients in the study group were predominantly affected with chronic plaque (73.1%), while joint involvement was seen in 12% of the patients. Ocular manifestations were seen in 55.4% of chronic plaque psoriasis patients, 55.6% of guttate psoriasis patients, 87.5% of erythrodermic psoriasis and 91.7% of psoriatic arthritis (significant p < 0.020 by Chi-square test). Erbagci et al reported ocular manifestations in 87.07% cases with psoriasis vulgaris, 86.79% with scalp psoriasis, and 43.75% with plaque psoriasis.15

About 47.5% patients with a PASI score less than 10, 62.7% patients with 10–20 PASI score and 76.9% of the patients with more than 20 PASI score presented with ocular manifestations (significant p value = 0.028). Ocular manifestations were more commonly seen in patients with a PASI score >10 when than in patients with PASI ≤ 10, and this difference was statistically significant. The results were comparable with the results of the study carried out by Maitray et al where about 50% patients with a PASI score less than 5, 72% patients with 5–10 PASI score and 74% patients with more than 10 PASI score developed ocular manifestations.

Out of 106 patients receiving only topical treatment in the form of topical corticosteroids and emollients, 55.7% patients had ocular manifestations. A total of 20 patients were receiving systemic treatment in the form of tablet methotrexate along with topical steroids and emollients in which 85% patients had ocular manifestations. The correlation was statistically significant (p < 0.023) by Chi-square test. The usage of topical steroids is a known risk factor for the development of the early cataract. We examined the patients to find out any significant trend of presenile or complicated cataract. No patient with presenile cataract or any other complicated cataract was noted in the study population. A similar study carried out by Chandran et al 3 in psoriasis patients found no significant relationship between cataracts of any type and topical steroid use.

Irritation (26.2%) followed by redness seen in 15.1% patients was the most common symptom seen in the study population, and blepharitis as ocular manifestation was seen in 15.9% of the patients. Lima et al16 in their study reported the incidence of blepharitis in the study population to be 12.5% which is comparable to our study. Conjunctival involvement in our study was seen as conjunctivitis in 7.1% patients, pinguecula in 5.6% patients and pterygium in 4.8% patients. However, pinguecula and pterygium are also seen commonly in the normal population, and it would be difficult to attribute these ocular manifestations completely to the disease process because this was a cross-sectional study and we did not have any age-sex matched controls. Lambert et al 17 reported conjunctivitis, pterygium and pinguecula in 11.6%, 5.33% and 8% patients, respectively. Episcleritis was seen in 4.0% of the patients, while scleritis was not seen in any patient. None of the patients in this study had corneal involvement in the form of opacity, vascularization or melting. Cataract was seen in 10.3% patients which was probably age related. Wanscher et al 10 in their study on 266 psoriasis reported that 188 (70%) had clear lenses and 66 (26%) presented with minute punctate opacities considered as physiological variations.

Uveitis was seen in 3.2% of patients. Out of 12 patients of psoriatic arthritis, 4 patients presented with anterior uveitis. Three patients (75%) of uveitis were seen in HLA B27–positive psoriatic arthritis, whereas one patient of uveitis (25%) had no correlation with HLA and was seen in HLA B27–negative psoriatic arthritis. The association was statistically significant (p value < 0.001) which has been proven in the previous studies.18,19 The patients had recurrent nongranulomatous anterior uveitis. One patient presented with acute anterior uveitis with spill over intermediate uveitis. The patients presented with the classical history of diminished vision associated with pain, redness and photophobia. Posterior segment involvement in uveitis is a relatively lesser-known entity. In our study, 3 patients had macular oedema, out of which 1 patient had vascular sheathing in the periphery along with macular oedema. This result is in congruence with a similar study carried out by Lambert et al who have reported the involvement of posterior segment in patients of psoriasis.17 Zeboulon et al 20 in a systematic review of 2987 patients for prevalence of uveitis in SpAs reported the prevalence of uveitis in SpA to be 32.7%.

There is an increased incidence of tear film abnormalities seen as dry eyes in patients with psoriasis.15 The dry eye syndrome and psoriasis may be correlated owing to the decreased concentration of l-arginine human cationic amino acid transporter in the skin affected by psoriasis because patients with both dry eye and psoriasis have been noted to have an l-arginine deficiency.21 In our study, dry eyes was the most common ocular manifestation observed in around 34 patients (27%) with reduced Schirmer-I level and decreased TBUT in 27 patients (21.4%). The value was statistically significant (p < 0.022) using Chi-square test. The test results suggest that basal secretion was more affected than reflex secretion. In psoriasis patient, tear film abnormalities may also be seen due to meibomian gland dysfunction or the presence of blepharitis. Both the Schirmers-1 test and the TBUT values depicted increasing severity of dry eye disease with the increase in psoriasis severity. This study has found maximal incidence of ocular manifestations in the age group above fifty, and dry eye was the predominant manifestation. Dry eye is also common in normal population aged 50 years and older. Hence, we cannot attribute all the dry eye findings to psoriasis as we did not have any age-sex-matched controls.

Her et al who evaluated dry eyes, tear film function and ocular surface changes in patients with psoriasis stated that dry eye symptom was more common in patients of psoriasis.21 Kilic et al noted Schirmer test and tear breakup time values to be statistically lower in the patient group than those in the control group.14 Also, in a study among the Brazilian patients with psoriatic arthritis, keratoconjunctivitis sicca was the commonest finding reported. 16

IOP was within the normal range in our study. The use of topical corticosteroids had not resulted in an increase in intraocular pressure nor development of glaucoma. In a similar study carried out by Lima et al, the mean intraocular pressure in psoriasis patients was reported to be normal.16

Conclusion

In our study, we tried to show the ocular manifestations of psoriasis in Indian population of western India which was 60.3%. There was no statistical correlation between the duration of the disease and ocular manifestation. The ocular manifestations were more common in patients with a PASI score >10 than in patients with a PASI score <10 and were seen frequently in the patients older than 51 years. Dry eyes and blepharitis are the most common ocular manifestations seen in psoriasis patients followed by episcleritis and uveitis. One of the limitations of the study was having an observational cross-sectional study; exclusion of pre-existing ocular conditions at times was difficult and had to rely on detailed history and extensive ocular examination. Owing to the multisystem involvement, a concerted medical approach is required for early detection and timely treatment of ocular manifestations in these patients. Therefore, routine ocular evaluations are recommended in all types of psoriasis patients, to screen for commonly associated ophthalmic conditions during their regular follow-up visits with dermatologists and rheumatologists for a comprehensive patient care.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgement

Department of Dermatology, AFMC, Pune, for their constant support in achieving the target sample size.

References

- 1.Strober B., Greenberg J.D., Karki C., et al. Impact of psoriasis severity on patient-reported clinical symptoms, health-related quality of life and work productivity among US patients: real-world data from the Corrona Psoriasis Registry. BMJ Open. 2019 Apr;9(4) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dogra S., Mahajan R. Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, co-morbidities, and clinical scoring. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7(6):471. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.193906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chandran N.S., Greaves M., Gao F., Lim L., Cheng B.C.L. Psoriasis and the Eye: Prevalence of Eye Disease in Singaporean Asian Patients with Psoriasis. J Dermatol. 2007 Dec;vol. 34(12):805–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2007.00390.x. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18078405 [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nestle F.O., Kaplan D.H., Barker J., Psoriasis N Engl J Med. 2009 Jul;361(5):496–509. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van De Kerkhof P.C.M., De Hoop D., De Korte J., Kuipers M.V. Scalp psoriasis, clinical presentations and therapeutic management. Dermatology. 1998;197(4):326–334. doi: 10.1159/000018026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Twilt M., Swart Van Den Berg M., Van Meurs J.C., Ten Cate R., Van Suijlekom-Smit L.W.A. Persisting uveitis antedating psoriasis in two boys. Eur J Pediatr. 2003 Sep 1;162(9):607–609. doi: 10.1007/s00431-003-1264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Power W.J., Rodriguez A., Pedroza-Seres M., Foster C.S. Outcomes in Anterior Uveitis Associated with the HLA-B27 Haplotype. Ophthalmology. 1998 Sep 1;vol. 105(9):1646–1651. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(98)99033-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9754172 [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Egeberg A., Khalid U., Gislason G.H., Mallbris L., Skov L., Hansen P.R. Association of psoriatic disease with Uveitis: a Danish nationwide cohort study. JAMA Dermatology. 2015 Nov 1;151(11):1200–1205. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anitha K., Anjaneyulu K., Reddy G.N., Reddy B.U., Geetha A. A ClinicalStudyof Ocular Manifestationsand Their Complications in Psoriasis. IOSR J Dent Med Sci e-ISSN. 2019;18:20–23. www.iosrjournals.org [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 27] Available from. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wanscher B., Vesterdal E. Syndermatotic Cataract in Patients with Psoriasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 1976:397–399. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/78627 [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 28] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meier M., Sheth P.B. Clinical spectrum and severity of psoriasis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2009;38:1–20. doi: 10.1159/000232301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maitray A., Bhandary A.S., Shetty S.B., Kundu G. Ocular manifestations in psoriasis. Int J Ocular Oncol Oculoplasty. 2016;2(2):123–131. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramana G.V., Malini P., Arun N. Patterns of psoriasis in patients attending DVL OPD at osmania general hospital-A prevalence study [internet] Int J Contemporary Med Res. 2017;4 www.ijcmr.com [cited 2020 Apr 28] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kilic B., Dogan U., Parlak A.H., et al. Ocular findings in patients with psoriasis. Int J Dermatol. 2013 May;52(5):554–559. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2011.05424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Erbagci I., Erbagci Z., Gungor K., Bekir N. Ocular anterior segment pathologies and tear film changes in patients with psoriasis vulgaris. Acta Med Okayama. 2003 Dec;57(6):299–303. doi: 10.18926/AMO/32810. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14726967 [Internet] [cited 2020 Apr 23] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lima F.B.F. de, Abalem M.F., Ruiz D.G., et al. Prevalence of eye disease in Brazilian patients with psoriatic arthritis. Clinics. 2012;67(3):249. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2012(03)08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert J.R., Wright V. Eye inflammation in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1976;35(4):354–356. doi: 10.1136/ard.35.4.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knox D.L. Psoriasis and intraocular inflammation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1979;77:210–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kammer G.M., Soter N.A., Gibson D.J., Schur P.H. Psoriatic arthritis: a clinical, immunologic and HLA study of 100 patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1979;9(2):75–97. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(79)80001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeboulon N., Dougados M., Gossec L. Prevalence and characteristics of uveitis in the spondyloarthropathies: a systematic literature review. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008 Jul;67(7):955–959. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.075754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Her Y., Lim J.W., Han S.H. Dry eye and tear film functions in patients with psoriasis. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2013 Jul;57(4):341–346. doi: 10.1007/s10384-012-0226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]