Abstract

Introduction

Chronic pain is a debilitating medical problem that is difficult to treat. Neuroinflammatory pathways have emerged as a potential therapeutic target, as preclinical studies have demonstrated that glial cells and neuroglial interactions play a role in the establishment and maintenance of pain. Recently, we used positron emission tomography (PET) to demonstrate increased levels of 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) binding, a marker of glial activation, in patients with chronic low back pain (cLBP). Cannabidiol (CBD) is a glial inhibitor in animal models, but studies have not assessed whether CBD reduces neuroinflammation in humans. The principal aim of this trial is to evaluate whether CBD, compared with placebo, affects neuroinflammation, as measured by TSPO levels.

Methods and analysis

This is a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase II clinical trial. Eighty adults (aged 18–75) with cLBP for >6 months will be randomised to either an FDA-approved CBD medication (Epidiolex) or matching placebo for 4 weeks using a dose-escalation design. All participants will undergo integrated PET/MRI at baseline and after 4 weeks of treatment to evaluate neuroinflammation using [11C]PBR28, a second-generation radioligand for TSPO. Our primary hypothesis is that participants randomised to CBD will demonstrate larger reductions in thalamic [11C]PBR28 signal compared with those receiving placebo. We will also assess the effect of CBD on (1) [11C]PBR28 signal from limbic regions, which our prior work has linked to depressive symptoms and (2) striatal activation in response to a reward task. Additionally, we will evaluate self-report measures of cLBP intensity and bothersomeness, depression and quality of life at baseline and 4 weeks.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol is approved by the Massachusetts General Brigham Human Research Committee (protocol number: 2021P002617) and FDA (IND number: 143861) and registered with ClinicalTrials.gov. Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at conferences.

Trial registration number

NCT05066308; ClinicalTrials.gov.

Keywords: Back pain, Magnetic resonance imaging, Clinical trials, PAIN MANAGEMENT, NEUROPHYSIOLOGY

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

To our knowledge, this is among the largest double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trials to evaluate a pain intervention using positron emission tomography.

This is the first trial to assess whether cannabidiol (CBD) may reduce neuroinflammation and pain symptoms in chronic low back pain patients.

This study will advance knowledge on mechanisms of action of CBD that may aid in treatment of other conditions and test whether neuroinflammation is a promising therapeutic target for pain.

The length of study drug administration is 4 weeks, which will limit our ability to assess potential long-term therapeutic effects of CBD.

Chronic low back pain is a broad category, encompassing mechanistically different etiologies, which could limit the ability to identify a specific mechanism of action of CBD.

Introduction

Chronic pain affects an estimated 50 to 100 million individuals in the USA1 2 and is among the most debilitating medical conditions with profound physical, emotional and economic costs.3 Available treatment options including interventional techniques4 and non-opioid pain medications such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs5 are often ineffective.6 Until recently, efforts to improve pain care led to increased use of opioids, contributing to an epidemic of opioid use disorder and opioid overdose deaths.7–9 In this setting of high public health need, there is a strong interest in discovering alternative therapeutic targets for chronic pain.

Animal studies have demonstrated that glial cells, as well as neuroglial interactions, play a key role in the establishment and maintenance of pain.10–15 In animal models of pain,16–18 activated glial cells10 19–36 initiate a series of cellular responses including increased expression of receptors and surface markers11 37 and production of inflammatory mediators10 38 that further sensitise pain pathways39 in a ‘pain-produces-pain’ loop. Importantly, agents that disrupt glial function inhibit or attenuate various behavioural markers of pain hypersensitivity (eg, thermal and mechanical hyperalgesia).35 36 40 41

Recently, our group used positron emission tomography (PET) to demonstrate the presence of increased levels of the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO), a marker of glial activation,16 42–50 in the brains51 and spinal cords52 of patients with chronic low back pain (cLBP) compared with controls. These TSPO signal elevations were consistently observed, particularly in the thalamus, in our original study51 and were later replicated in an independent cLBP cohort.53 We therefore consider this signal as a potential marker of ‘pain-related’ neuroinflammation in cLBP. These observations, along with results from studies showing brain TSPO signal elevation in fibromyalgia, Gulf War Illness, migraine and others,54–57 suggest a role of neuroinflammation across these conditions and present a potential therapeutic target for pain disorders.

The endocannabinoid system plays a key role in regulation of pain sensation.58 59 Thus, cannabidiol (CBD), a non-intoxicating compound in the cannabis plant, could potentially be effective for treating pain. CBD is thought to be a weak inverse agonist of both cannabinoid 1 (CB1) and cannabinoid 2 (CB2) receptors58 as well as an allosteric modulator of other receptors related to pain.60 Both cannabinoid CB1 (found at presynaptic sites throughout the peripheral and central nervous systems) and CB2 (found principally on immune cells) receptors are being evaluated as potential therapeutic targets for pain disorders.61 62 Because CBD can behave as a CB2 receptor inverse agonist, this may account for its anti-inflammatory properties.63

Animal models have identified a role for both CB1 and CB2 receptor activation in reducing neuropathic and inflammatory pain,58 and several preclinical studies have suggested that systemic administration of cannabinoid receptor ligands produces analgesia in acute and chronic pain models.59 In animals, CBD induces analgesic64–66 and antidepressant67 68 effects via a complex pathway that includes the inhibition of proinflammatory pathways in glial cells.69

Although some preclinical studies provide evidence for the effectiveness of CBD for pain, results from clinical studies have been inconsistent. A recent report from our group found no significant effect of cannabis on pain,70 supporting conclusions from a Cochrane review, which concluded that there was no strong evidence for the effectiveness of cannabis-derived products for chronic pain.71 However, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine reported that there was substantial evidence that cannabis was effective in treating chronic pain.72 Such inconsistencies may be partially explained by heterogeneity in methods across studies (with some lacking a placebo control), by the fact that meta-analyses often combine results from studies using various combinations and doses of cannabinoids73 74 (eg, varying THC (tetrahydrocannabinol)/CBD potencies), and by combining studies addressing different kinds of pain. Perhaps more problematic is the fact that many commercial CBD products available are of unknown quality and contain variable doses of the active ingredient.75 In the current study, we will use Epidiolex, the first and only FDA-approved drug containing a known and consistent dose of purified CBD. Thus, the current study will assess whether an FDA-approved CBD formulation, in a known dose, compared with placebo, reduces neuroinflammation in patients with cLBP. Such reduction may be the result of a direct effect of CBD on CB receptors expressed in glia, as mentioned above. However, given the emerging evidence of an effect of CBD on voltage-gated sodium channels in primary nociceptors in the mouse,76 CBD may work by normalising aberrant neural activity and, therefore, reduce neurogenic neuroinflammation.77

This study will also assess the role of CBD on neuroinflammation with respect to depressive symptoms. Comorbid depression and chronic pain are common, with approximately 40% of patients with cLBP also exhibiting negative affect, including depressive symptoms.78–81 Depression has been associated with neurobiological changes, including neurotransmitter deficits, endocrine disturbances and impaired neural adaptation and plasticity,82 83 and neuroinflammation may be implicated in these abnormalities.84 Those with depression who commit suicide have shown dramatically increased microglial activation.85 Indeed, cLBP patients who also have comorbid depression demonstrate, in addition to thalamic TSPO signal elevations observed irrespectively of depression status, TSPO signal elevations in limbic regions, which are proportional to scores on the Beck Depression Inventory.86 Meta-analyses have shown that mechanistically diverse anti-inflammatory agents may be effective treatments for depression.87–89 Preliminary evidence suggests that CBD promotes antidepressant effects in animal models;67 68 however, randomised clinical trials of CBD for treatment of depression have not been conducted. Therefore, a secondary objective of the study is to assess whether CBD compared with placebo reduces depressive symptomatology and depression-related neuroinflammation in patients with cLBP.

Healthcare providers are increasingly interacting with patients who are interested in using CBD for various pain disorders, with little evidence available for therapeutic guidance. Results from this study will provide critical information regarding the potential utility of CBD for cLBP and its involvement in mechanistic pathways of neuroinflammation.

Methods and analysis

The full protocol is included as supplementary information (see online supplemental file 1).

bmjopen-2022-063613supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

Study design

This is a phase II, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled 4-week clinical trial with a 6-week follow-up assessment. The principal goals of this trial are to assess the effects of CBD on neuroinflammation, pain and depressive symptomatology, in participants with cLBP. Neuroinflammation will be quantified with PET/MRI scans using [11C]PBR28, a second-generation ligand for TSPO. Participants will continue their usual pain care regimen during the study. This trial is being conducted at Massachusetts General Hospital in the USA. The study is currently in progress; the first participant was enrolled in January 2022, and the last participant is expected to be enrolled in 2026.

Participants

We will recruit a total of 80 cLBP patients aged 18–75 through clinical research databases, physician referrals, clinical programs associated with the healthcare systems and community advertising. Participants must have a diagnosis of cLBP for at least 6 months and must report worst daily pain of at least a 4 on a 0–10 scale of pain intensity during a typical day, and pain present for at least 3–4 days during a typical week. Participants will be genotyped for the Ala147Thr TSPO polymorphism (rs6971) using blood or saliva. Approximately 10% of humans show low binding to the PET radioligand used in this study, [11C)]PBR2890; the rs6971 polymorphism allows for the identification of low, mixed or high affinity binders.91 92 In this study, only high or mixed-affinity binders will be considered eligible. Any ongoing pain treatment (pharmacologic or behavioral) must be stable for 4 weeks prior to randomisation.

Exclusion criteria include: abnormal liver function test results, contraindications to PET/MRI scanning, unresolved neurological or major medical illness, use of medications deemed to have unsafe interactions with Epidiolex, use of marijuana in the previous 2 weeks or regular recreational drug use in the previous 3 months. See table 1 for the full list of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

AEs, adverse events; AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CBD, cannabidiol; CNS, Central Nervous System; PET, positron emission tomography; PTSD, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; TSPO, translocator protein.

Participant enrollment

Participants will undergo a telephone screen or complete an online screening survey. Those who are likely to be eligible based on their responses will be scheduled for a screening visit where study procedures will be explained and informed consent will be obtained (see online supplemental file 2 for a copy of the consent form). Eligibility assessments will be conducted during the screening visit, listed in table 2.

Table 2.

Schedule of assessments

| Assessment | Screen | Baseline scan | Week 1 | Week 2 | Week 3 | Post-Tx scan (Week 4) | Week 6 | |

| Eligibility and safety assessments | Consent form | x | ||||||

| Characterisation of pain | x | |||||||

| Physical examination | x | |||||||

| Medical history | x | |||||||

| Concomitant medications | x | x | ||||||

| Adverse events | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| C-SSRS (suicidality) | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Urine drug test (10-Panel) | x | x | x | |||||

| Urine pregnancy test | x | |||||||

| Serum pregnancy test | x | x | ||||||

| Liver function tests | x | x | ||||||

| Primary outcome | [11C]PBR28 Signal in Thalamus | x | x | |||||

| Secondary outcomes | [11C]PBR28 Signal in Limbic Regions (pgACC, aMCC) | x | x | |||||

| ‘Worst Pain’ item of BPI-SF (0–10 scale) | Daily survey ratings from~2 weeks before scan I until Week 6 | |||||||

| Pain Bothersomeness Ratings (0–10 scale) | Daily survey ratings from~2 weeks before scan I until Week 6 | |||||||

| BDI-II | x | x | x | x | ||||

| PGIC | x | |||||||

| Exploratory outcomes | Reward Task (MID) | x | x | |||||

| BPI-SF | x | x | x | x | ||||

| PCS | x | x | x | x | ||||

| PainDETECT | x | x | ||||||

| ODI | x | x | ||||||

| ACR Fibromyalgia Survey | x | x | x | |||||

| Depression Ratings (0–10 scale) | Daily survey ratings from~2 weeks before scan I until week 6 | |||||||

| PROMIS-29 | x | x | ||||||

| PSQI | x | x | x | |||||

| SymptomMapper | x | x | ||||||

BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory; BPI-SF, Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form; MID, Monetary Incentive Delay Task; ODI, Oswestry Disability Index; PCS, Pain Catastrophizing Scale; PGIC, Patient Global Impression of Change; PROMIS-29, Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–29; PSQI, Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index.

bmjopen-2022-063613supp002.pdf (13.7MB, pdf)

Investigational product

Participants will be randomised to receive Epidiolex or placebo, both provided by Jazz Pharmaceuticals. Epidiolex is FDA approved for the treatment of certain forms of epilepsy. It is a 100 mg/mL purified oral solution dissolved in sesame oil and anhydrous ethanol with sucralose and strawberry flavouring. The drug is formulated from extracts prepared from Cannabis sativa L. plants that have a defined chemical profile and contain consistent levels of CBD as the principal phytocannabinoid. Extracts from these plants are processed to yield pure (>95%) CBD that typically contains less than 0.5% THC.

Participants will follow a dose escalation schedule based on Epidiolex package insert recommendations, with 2.5 mg/kg taken orally two times per day in week 1, 5 mg/kg two times per day in week 2, 7.5 mg/kg two times per day in week 3 and 10 mg/kg two times per day in week 4. If participants report significant adverse events (AEs) (eg, tiredness, dizziness, not tolerating the drug well, significant weight change) during the second, third or fourth week of taking the study drug, the study physician will decrease the dose of study drug to the previous week’s dose.

Randomisation and treatment allocation

Eligible participants will be enrolled by study staff and randomised to receive either CBD or placebo. Stratified simple random sampling, based on age (>50 vs ≤50) and sex (male vs female), will be performed. Randomisation sheets have been developed by the study biostatistician and will be used by a study pharmacist to assign treatments. The MGH Clinical Trials pharmacy will handle the blinding of study medication, and all members of the study clinical staff and study participants will be blinded to treatment assignment.

Study procedure

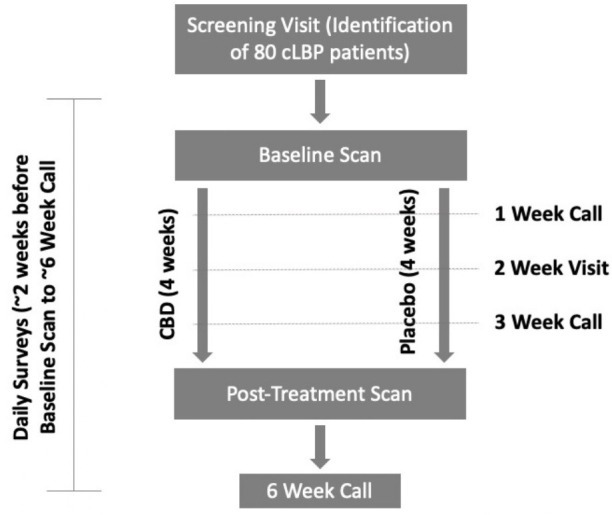

See figure 1 for the study schema and table 2 for the schedule of assessments to be performed at each visit. Following randomisation, participants will be scheduled for a baseline PET/MRI scan. At this visit, participants will receive CBD or placebo, which they will be instructed to take daily for 4 weeks. Participants will be reminded to follow their study drug dose escalation at a weekly phone check-in. The post-treatment scan will take place at the end of week 4. Questionnaires assessing pain, depression, sleep and other constructs (see table 2) will be collected at baseline and week 4. AEs will be assessed at baseline and weeks 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6 (2 weeks after the discontinuation of the study drug) and expected improvement from treatment will be assessed at baseline and weeks 1, 2 and 3. In the case of scans scheduled more than 4 weeks apart, the participant will be instructed to start taking the study drug exactly 4 weeks before the post-treatment scan. Blood samples will be collected at baseline and week 4, to be assayed for CBD and its metabolites.

Figure 1.

Study schema. CBD, cannabidiol; cLBP, chronic low back pain.

PET/MRI scans

On the scan day, participants will complete screening checklists for PET/MRI to determine whether they have any contraindications for the test. A urine drug test will also be performed, and female participants of childbearing potential will have blood drawn to perform a serum pregnancy test.

At the beginning of the scan sessions, an intravenous catheter will be placed in the participant’s antecubital vein of the left or right arm. Blood will be drawn to assess quantitative levels of cannabinoids, including CBD and THC. An arterial line will be placed in a radial artery with local anaesthesia if the participant has consented to this (optional) procedure and has no contraindications. The arterial line will be placed in the arm contralateral to the intravenous line that is used for the [11C]PBR28 radiotracer injection and will enable blood sampling at various times during the imaging study for at most 160 mL of blood. The collected arterial blood will be used to compute metabolite-corrected arterial input function for kinetic modelling analyses. Brain PET/MRI data will be acquired for approximately 90 min postinjection. Between 90 min and 110 min post-injection, we may acquire spinal cord data from the thoracic and upper lumbar spine and evaluate the signal from the most caudal segments of the spinal cord, as this region also demonstrated neuroinflammation in our prior study of patients with lumbar radiculopathy.52

Our primary metric for brain [11C]PBR28 signal quantification will be standardised uptake value ratio (SUVR), using the whole brain as a normalising factor (as described in prior work51 53 93). In patients with arterial blood data available, we will compute distribution volume (VT) and ratio of distribution volume, which will be used as secondary outcome measures and to support the use of SUVR as an outcome metric. For spinal cord analyses, signal will be quantified by normalising the signal from the lowest 1–2 spinal segments present in the field of view for most/all of our participants (eg, T11-L1) with that of the uppermost 2–3 segments (eg, T7-T9) as in Albrecht et al.52

In addition to PET scans, other neuroimaging measures (Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) resting-state functional connectivity, 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), and arterial spin labelling (ASL)) measures will be collected. We will also collect fMRI measures during a reward task (Monetary Incentive Delay Task94). We have previously used this task to demonstrate striatal hypofunction, linked to depressive symptoms and anhedonia, in patients with cLBP.95

Daily surveys

Beginning 2 weeks before the first scan to week 6, participants will complete online daily surveys assessing various domains, including their clinical pain ratings (as measured by the ‘worst pain’ item of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form, BPI-SF93), pain bothersomeness ratings and depression ratings, each on a 0–10 scale. Participants will be asked to confirm daily medication adherence and will be asked about use of additional medications for pain management.

Data management

Data will be collected and entered by study staff into a REDCap database,96 which has been designed and completed by the study team. Data obtained during assessments administered by study staff will be entered by study staff. Following each visit, data will be checked by the data manager and/or research coordinator to ensure data quality and completeness. All PET/MRI scans will undergo standard quality control to look for imaging artifacts. For instance, any participant whose scan shows excessive head movement (eg, between-frame motion that cannot be easily corrected in post-processing) or issues with attenuation correction that cannot be remediated via post-processing will be excluded from final analyses. Daily survey data will be included for participants responding to at least half of the daily surveys, including at least four of the seven daily surveys during the fourth week of study drug administration.

Statistical plan

A generalised linear mixed-effects model (GLMM) will be used to quantify the association between thalamic [11C]PBR28 PET signal, treatment assignment at randomisation (CBD, placebo; intent-to-treat) and time (baseline, week 4). The unadjusted model will only regress PET signal onto treatment and time indicators as well as their interaction. An adjusted model will also be constructed that independently accounts for potentially confounding variables (eg, age, depression severity, sex). Data dependencies will be accounted for using either random intercept or line (intercept and slope) parameterisations. To fully specify our GLMMs, we will initially consider the Gaussian family (identity link). Since PET signal is a strictly positive quantity, we will also consider the binomial family with the cumulative logit link. A residual analysis will be performed to assess modelling assumptions and guide our choice in determining the final model.

Our primary object of inference will be the treatment by time interaction, which reflects the absolute difference in the rates of change in PET signal between treatment groups (Gaussian family) or the relative change in odds of having a higher PET signal between treatment groups (binomial family) when holding all other covariates fixed. Linear combinations of parameter estimates will also be computed to summarise secondary objects of interest, including cross-sectional treatment comparisons (baseline: CBD vs control; week 4: CBD vs control) and treatment-specific temporal comparisons (CBD: week 4 vs baseline; control: week 4 vs baseline).

This analysis plan will be repeated using a per-protocol definition of treatment in which we omit subjects who did not reliably take the study medication. Additional secondary and exploratory analyses (box 1) will follow a similar analysis plan as described above. For these non-primary analyses, we will account for multiple comparisons by computing both unadjusted p values and false discovery rate adjusted p values.97 Since we are randomising the treatment groups, confounding variables should be balanced between the groups—and, thus, we do not plan to adjust for confounding variables. However, if we do find that despite randomisation, there are imbalances between groups, we will adjust for potential confounding variables using directed acyclic graphs to determine which confounders may be an issue, and will control for these variables.

Box 1. Outcome measures.

Primary outcome measure

Translocator protein (TSPO) signal from the thalamus (as measured with [11C]PBR28 PET).

Secondary outcome measures

Daily clinical pain ratings (as measured by the ‘worst pain’ item of the Brief Pain Inventory-Short Form (BPI-SF) assessed in daily surveys).

TSPO signal from limbic regions (pregenual anterior cingulate cortex (pgACC) and anterior midcingulate cortex (aMCC); as measured with [11C]PBR28 PET).

Daily pain bothersomeness ratings (daily survey).

Depressive symptoms (Beck Depression Inventory, BDI-II105)*.

Quality of life (Patient Global Impression of Change*; assessed at post-treatment scan only).

Correlation between reductions in TSPO signal from the thalamus (as measured with [11C]PBR28 PET) and reductions in clinical pain ratings.

Correlation between reductions in TSPO signal from limbic regions (as measured with [11C]PBR28 PET) and reductions in depressive symptoms (as measured by BDI-II).

Exploratory outcome measures

Pain severity and interference (BPI-SF)*.

Pain catastrophising (Pain Catastrophizing Scale106)*.

Neuropathic pain (PainDETECT107)*.

Disability related to low back pain (Oswestry Disability Index108)*.

Widespread pain and fibromyalgia symptom severity (American College of Rheumatology’s fibromyalgia survey109)*.

Daily depression ratings (daily survey).

Widespreadness of pain sensation (SymptomMapper app110).

Health-related quality of life (Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System–29111)*.

Sleep quality (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index112)*.

Spinal cord TSPO signal (as measured with(11C)PBR28 PET).

Striatal activation to a reward task (Monetary Incentive Delay Task94).

-

Other neuroimaging measures (Diffusion Tensor Imaging, Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD) resting-state functional connectivity, 1H-magnetic resonance spectroscopy to measure brain metabolites and ASL).

*Total score of these measures will be used in analyses.

Outcome measures

Power justification

Primary outcome. Using a linear mixed-effects model, we estimate the power to detect a temporal (week 4—baseline) rate of change in thalamic [11C)]PBR28 PET signal between CBD and control subjects when recruiting 40 subjects per treatment group. We assume: (1) the SD of the [11C)]PBR28 PET signal measures are 0.05,98 (2) the correlation between repeated measurements ranges between 0.3 and 0.8 and (3) the attrition rate ranges between 5% and 15% and the type-I error is 0.05. If the within-subject correlation is 0.3, and the attrition rate for both treatment groups is 10%, then we will have 80% and 90%, power to detect mean differences in [11C]PBR28 PET signal measures of at least 0.039 and 0.045, respectively (table 3).

Table 3.

Detectable mean differences in rates of SUVR change between treatment groups as a function of within subject correlation, attrition, sample size and power

| Within subject correlation | Attrition, % | Sample size | Detectable mean difference | |

| Power=0.80 | Power=0.90 | |||

| 0.3 | 0 | 80(40/40) | 0.037 | 0.042 |

| 0.3 | 5 | 76(38/38) | 0.038 | 0.044 |

| 0.3 | 10 | 72(36/36) | 0.039 | 0.045 |

| 0.3 | 15 | 68(34/34) | 0.040 | 0.047 |

| 0.5 | 0 | 80(40/40) | 0.031 | 0.036 |

| 0.5 | 5 | 76(38/38) | 0.032 | 0.037 |

| 0.5 | 10 | 72(36/36) | 0.033 | 0.038 |

| 0.5 | 15 | 68(34/34) | 0.034 | 0.039 |

| 0.8 | 0 | 80(40/40) | 0.020 | 0.023 |

| 0.8 | 5 | 76(38/38) | 0.020 | 0.024 |

| 0.8 | 10 | 72(36/36) | 0.021 | 0.024 |

| 0.8 | 15 | 68(34/34) | 0.021 | 0.025 |

Missing data

All attempts will be made to minimise missing data, but, if present, we plan to multiply impute all missing imaging and behavioral data and make inferences using combined estimates of the fixed effects and their covariance matrices.99 As a sensitivity analysis, we will repeat each analysis on the subset of subjects with complete imaging or behavioral data.

Adverse events

From the baseline scan to week 6, research coordinators will ask participants on a weekly basis to report any AEs (eg, tiredness, decreased appetite, diarrhoea), and, together with the study physicians and principal investigators, will assess the severity of the events and whether the event is related to their participation in the study. A serious AE is an event that is deemed life threatening, requires hospitalisation, causes permanent damage or requires medical intervention to prevent permanent damage or results in death. Reporting and handling of AEs will be in accordance with Institutional Review Board regulations and good clinical practice guidelines.

Unblinding

All members of the trial team and patients are blinded to the trial drug throughout the trial. Unblinding will only occur if a participant experiences an AE for which the clinical management of the AE will be facilitated by the unblinding of the participant’s treatment allocation. All recruited participants will be given contact details for the trial team, including emergency contact available 24 hours a day, 7 days per week.

Data and safety monitoring

A Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB) has been established for this study, consisting of a statistician, a pain expert and a psychiatrist (see online supplemental file 3 for DSMB Charter). The DSMB members have no competing interests and will ensure the safe use of the study drug throughout the project. The DSMB will also monitor the occurrence of all AEs on a quarterly basis. To perform this function, the DSMB will have independent access as necessary to the study drug code, indicating on which date the subject received CBD or placebo. The DSMB will review all unanticipated problems involving risk to participants or others, serious AEs. The DSMB will comment on the outcomes of the event and, in the case of a serious AE, determine the relationship to participation in the study.

bmjopen-2022-063613supp003.pdf (64.4KB, pdf)

Interim analyses will be performed on study data only when requested by the DSMB to assess the safety and efficacy of the ongoing study. The results of these analyses will be made available to the Institutional Review Board and the National Institute on Drug Abuse in accordance with annual reporting requirements or sooner if necessary.

Early termination of the trial

The DSMB will monitor the occurrence of all AEs on a quarterly basis to ensure that their rate and severity are acceptable within the overall risk/benefit ratio of the study.

Withdrawal from the study

Participation in this study is voluntary and individuals may choose to stop participation at any time. Participants will be told at consent to inform study staff if they wish to stop taking the study drug at any point, and reasons for withdrawal will be documented. Those who choose to stop taking the study drug will be asked to continue to follow the schedule of visits if they are willing. The study physician may also withdraw a participant from the study without their permission if they cannot follow the study plan, or for medical reasons such as side effects from the study drug.

Confidentiality

Study staff will adhere to the confidentiality requirements set by the Massachusetts General Brigham Human Research Committee. Data on computers will be password protected, and all paper records are secured in a locked office. Any samples that are stored will be labeled with a code; no names or other identifying information will be on these samples.

Patient and public involvement

Neither patients nor the public were involved in the development, design and conduct of this study. Results of the study will be shared with the public through conference presentations and publications in peer-reviewed journals.

Ethics and dissemination

This protocol is approved by the Massachusetts General Brigham Human Research Committee (Protocol Number: 2021P002617) and the United States Food and Drug Administration (IND number: 143861). Informed consent will be obtained from all participants by a physician, nurse practitioner or the principal investigator. Important protocol modifications will be submitted to the Human Research Committee for approval and then communicated to participants. Findings from this trial will be presented in peer-reviewed journals and at national conferences. Data will be deidentified in all cases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: JMG and MLL developed and designed the trial and obtained funding for the trial. CKP and MK wrote the first draft of this manuscript. JMG, MLL, KS, RE, VN, YZ, ZA, AEE, CKP and MK assisted with the study design. NM designed the statistical aspects of this protocol. JMG, MLL, CKP, MK, KS, NM, RE, VN, YZ, EJM, ZA and AEE were involved in the revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final version to be submitted.

Funding: This work is supported by NIH grant number 1R01DA053316-01. The NIH has not had nor will have any role in the design of the study, the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of data, the writing of manuscripts, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Competing interests: The study drug was donated by Jazz Pharmaceuticals. MLL consulted for Shionogi in 2018. AEE reported receiving grants from Charles River Analytics and nonfinancial support from Pfizer as well as serving as the chair of the data monitoring board of Karuna Pharmaceuticals outside the submitted work. VN consults for Cala Health, Inc. and Click Therapeutics, Inc.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of Chronic Pain and High-Impact Chronic Pain Among Adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018;67:1001–6. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harstall C. How prevalent is chronic pain? Pain: Clinical Updates 2003:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manchikanti L, Singh V, Kaye AD, et al. Lessons for better pain management in the future: learning from the past. Pain Ther 2020;9:373–91. 10.1007/s40122-020-00170-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Manchikanti L, Sanapati MR, Pampati V, et al. Update on Reversal and Decline of Growth of Utilization of Interventional Techniques In Managing Chronic Pain in the Medicare Population from 2000 to 2018. Pain Physician 2019;22:521–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis A, Robson J. The dangers of NSAIDs: look both ways. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:172–3. 10.3399/bjgp16X684433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manchikanti L, Vallejo R, Manchikanti KN, et al. Effectiveness of long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pain Physician 2011;14:E133–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuehn BM. Opioid prescriptions soar: increase in legitimate use as well as abuse. JAMA 2007;297:249–51. 10.1001/jama.297.3.249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manchikanti L, Damron KS, McManus CD, et al. Patterns of illicit drug use and opioid abuse in patients with chronic pain at initial evaluation: a prospective, observational study. Pain Physician 2004;7:431–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Substance A. Mental Health Services, Substance abuse treatment admissions involving abuse of pain relievers: 1998 and 2008, 2010. Available: http://oas.samhsa.gov/2k10/230/230PainRelvr2k10.cfm

- 10.Ji R-R, Berta T, Nedergaard M. Glia and pain: is chronic pain a gliopathy? Pain 2013;154 Suppl 1:S10–28. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tsuda M, Shigemoto-Mogami Y, Koizumi S, et al. P2X4 receptors induced in spinal microglia gate tactile allodynia after nerve injury. Nature 2003;424:778–83. 10.1038/nature01786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvo M, Dawes JM, Bennett DLH. The role of the immune system in the generation of neuropathic pain. Lancet Neurol 2012;11:629–42. 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70134-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watkins LR, Hutchinson MR, Ledeboer A, et al. Norman Cousins Lecture. Glia as the "bad guys": implications for improving clinical pain control and the clinical utility of opioids. Brain Behav Immun 2007;21:131–46. 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madiai F, Hussain S-RA, Goettl VM, et al. Upregulation of FGF-2 in reactive spinal cord astrocytes following unilateral lumbar spinal nerve ligation. Exp Brain Res 2003;148:366–76. 10.1007/s00221-002-1286-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen W, Walwyn W, Ennes HS, et al. Bdnf released during neuropathic pain potentiates NMDA receptors in primary afferent terminals. Eur J Neurosci 2014;39:1439–54. 10.1111/ejn.12516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ji B, Maeda J, Sawada M, et al. Imaging of peripheral benzodiazepine receptor expression as biomarkers of detrimental versus beneficial glial responses in mouse models of Alzheimer's and other CNS pathologies. J Neurosci 2008;28:12255–67. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2312-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haythornthwaite JA, Sieber WJ, Kerns RD. Depression and the chronic pain experience. Pain 1991;46:177–84. 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90073-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Krause SJ, Wiener RL, Tait RC. Depression and pain behavior in patients with chronic pain. Clin J Pain 1994;10:122–7. 10.1097/00002508-199406000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gosselin R-D, Suter MR, Ji R-R, et al. Glial cells and chronic pain. Neuroscientist 2010;16:519–31. 10.1177/1073858409360822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholz J, Woolf CJ. The neuropathic pain triad: neurons, immune cells and glia. Nat Neurosci 2007;10:1361–8. 10.1038/nn1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ji R-R, Suter MR. p38 MAPK, microglial signaling, and neuropathic pain. Mol Pain 2007;3: :33. 10.1186/1744-8069-3-33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colburn RW, Rickman AJ, DeLeo JA. The effect of site and type of nerve injury on spinal glial activation and neuropathic pain behavior. Exp Neurol 1999;157:289–304. 10.1006/exnr.1999.7065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fu KY, Light AR, Matsushima GK, et al. Microglial reactions after subcutaneous formalin injection into the rat hind paw. Brain Res 1999;825:59–67. 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01186-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Zhao YQ, Ribeiro-da-Silva A, et al. Distinctive response of CNS glial cells in orofacial pain associated with injury, infection and inflammation. Mol Pain 2010;6:79. 10.1186/1744-8069-6-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei F, Guo W, Zou S, et al. Supraspinal glial-neuronal interactions contribute to descending pain facilitation. J Neurosci 2008;28:10482–95. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3593-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Hoffert C, Vu HK, et al. Induction of CB2 receptor expression in the rat spinal cord of neuropathic but not inflammatory chronic pain models. Eur J Neurosci 2003;17:2750–4. 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02704.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin S-X, Zhuang Z-Y, Woolf CJ, et al. P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase is activated after a spinal nerve ligation in spinal cord microglia and dorsal root ganglion neurons and contributes to the generation of neuropathic pain. J Neurosci 2003;23:4017–22. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04017.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhuang Z-Y, Kawasaki Y, Tan P-H, et al. Role of the CX3CR1/p38 MAPK pathway in spinal microglia for the development of neuropathic pain following nerve injury-induced cleavage of fractalkine. Brain Behav Immun 2007;21:642–51. 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller TR, Wetter JB, Jarvis MF, et al. Spinal microglial activation in rat models of neuropathic and osteoarthritic pain: an autoradiographic study using [3H]PK11195. Eur J Pain 2013;17:692–703. 10.1002/j.1532-2149.2012.00232.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Echeverry S, Shi XQ, Zhang J. Characterization of cell proliferation in rat spinal cord following peripheral nerve injury and the relationship with neuropathic pain. Pain 2008;135:37–47. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beggs S, Salter MW. Stereological and somatotopic analysis of the spinal microglial response to peripheral nerve injury. Brain Behav Immun 2007;21:624–33. 10.1016/j.bbi.2006.10.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Calvo M, Bennett DLH. The mechanisms of microgliosis and pain following peripheral nerve injury. Exp Neurol 2012;234:271–82. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L, Rudin M, Kozlova EN. Glial cell proliferation in the spinal cord after dorsal rhizotomy or sciatic nerve transection in the adult rat. Exp Brain Res 2000;131:64–73. 10.1007/s002219900273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beggs S, Trang T, Salter MW. P2X4R+ microglia drive neuropathic pain. Nat Neurosci 2012;15:1068–73. 10.1038/nn.3155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo W, Wang H, Watanabe M, et al. Glial-cytokine-neuronal interactions underlying the mechanisms of persistent pain. J Neurosci 2007;27:6006–18. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0176-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Okada-Ogawa A, Suzuki I, Sessle BJ, et al. Astroglia in medullary dorsal horn (trigeminal spinal subnucleus caudalis) are involved in trigeminal neuropathic pain mechanisms. J Neurosci 2009;29:11161–71. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3365-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Verge GM, Milligan ED, Maier SF, et al. Fractalkine (CX3CL1) and fractalkine receptor (CX3CR1) distribution in spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia under basal and neuropathic pain conditions. Eur J Neurosci 2004;20:1150–60. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03593.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen G, Park C-K, Xie R-G, et al. Connexin-43 induces chemokine release from spinal cord astrocytes to maintain late-phase neuropathic pain in mice. Brain 2014;137:2193–209. 10.1093/brain/awu140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mika J. Modulation of microglia can attenuate neuropathic pain symptoms and enhance morphine effectiveness. Pharmacol Rep 2008;60:297–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meller ST, Dykstra C, Grzybycki D, et al. The possible role of glia in nociceptive processing and hyperalgesia in the spinal cord of the rat. Neuropharmacology 1994;33:1471–8. 10.1016/0028-3908(94)90051-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watkins LR, Martin D, Ulrich P, et al. Evidence for the involvement of spinal cord glia in subcutaneous formalin induced hyperalgesia in the rat. Pain 1997;71:225–35. 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)03369-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abourbeh G, Thézé B, Maroy R, et al. Imaging microglial/macrophage activation in spinal cords of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis rats by positron emission tomography using the mitochondrial 18 kDa translocator protein radioligand [¹⁸F]DPA-714. J Neurosci 2012;32:5728–36. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2900-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banati RB, Newcombe J, Gunn RN, et al. The peripheral benzodiazepine binding site in the brain in multiple sclerosis: quantitative in vivo imaging of microglia as a measure of disease activity. Brain 2000;123 (Pt 11:2321–37. 10.1093/brain/123.11.2321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vowinckel E, et al. PK11195 binding to the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor as a marker of microglia activation in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis - Vowinckel - 1997. J Neurosci Res 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen M-K, Baidoo K, Verina T, et al. Peripheral benzodiazepine receptor imaging in CNS demyelination: functional implications of anatomical and cellular localization. Brain 2004;127:1379–92. 10.1093/brain/awh161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen M-K, Guilarte TR. Imaging the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor response in central nervous system demyelination and remyelination. Toxicol Sci 2006;91:532–9. 10.1093/toxsci/kfj172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cosenza-Nashat M, Zhao M-L, Suh H-S, et al. Expression of the translocator protein of 18 kDa by microglia, macrophages and astrocytes based on immunohistochemical localization in abnormal human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2009;35:306–28. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2008.01006.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venneti S, Wang G, Wiley CA. Activated macrophages in HIV encephalitis and a macaque model show increased [3H](R)-PK11195 binding in a PI3-kinase-dependent manner. Neurosci Lett 2007;426:117–22. 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.08.053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martín A, Boisgard R, Thézé B, et al. Evaluation of the PBR/TSPO radioligand [(18)F]DPA-714 in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010;30:230–41. 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rojas S, Martín A, Arranz MJ, et al. Imaging brain inflammation with [(11)C]PK11195 by PET and induction of the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor after transient focal ischemia in rats. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2007;27:1975–86. 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loggia ML, Chonde DB, Akeju O, et al. Evidence for brain glial activation in chronic pain patients. Brain 2015;138:604–15. 10.1093/brain/awu377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Albrecht DS, Ahmed SU, Kettner NW, et al. Neuroinflammation of the spinal cord and nerve roots in chronic radicular pain patients. Pain 2018;159:968–77. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Torrado-Carvajal A, Toschi N, Albrecht DS, et al. Thalamic neuroinflammation as a reproducible and discriminating signature for chronic low back pain. Pain 2021;162:1241–9. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Albrecht DS, Forsberg A, Sandström A, et al. Brain glial activation in fibromyalgia - A multi-site positron emission tomography investigation. Brain Behav Immun 2019;75:72–83. 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Alshelh Z, Albrecht DS, Bergan C, et al. In-vivo imaging of neuroinflammation in veterans with Gulf War illness. Brain Behav Immun 2020;87:498–507. 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hadjikhani N, Albrecht DS, Mainero C, et al. Extra-xial inflammatory signal in Parameninges in migraine with visual aura. Ann Neurol 2020;87:939–49. 10.1002/ana.25731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Albrecht DS, Mainero C, Ichijo E, et al. Imaging of neuroinflammation in migraine with aura: A [11C]PBR28 PET/MRI study. Neurology 2019;92:e2038–50. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000007371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pertwee RG. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and Delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br J Pharmacol 2008;153:199–215. 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walker JM, Huang SM. Cannabinoid analgesia. Pharmacol Ther 2002;95:127–35. 10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00252-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McPartland JM, Duncan M, Di Marzo V, et al. Are cannabidiol and Δ(9) -tetrahydrocannabivarin negative modulators of the endocannabinoid system? A systematic review. Br J Pharmacol 2015;172:737–53. 10.1111/bph.12944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang W-J, Chen W-W, Zhang X. Endocannabinoid system: role in depression, reward and pain control (review). Mol Med Rep 2016;14:2899–903. 10.3892/mmr.2016.5585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Woodhams SG, Sagar DR, Burston JJ, et al. The role of the endocannabinoid system in pain. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2015;227:119–43. 10.1007/978-3-662-46450-2_7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pertwee RG. Pharmacological actions of cannabinoids. Handb Exp Pharmacol 2005;168:1–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Crivelaro do Nascimento G, Ferrari DP, Guimaraes FS, et al. Cannabidiol increases the nociceptive threshold in a preclinical model of Parkinson's disease. Neuropharmacology 2020;163:107808. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.107808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wong H, Cairns BE. Cannabidiol, cannabinol and their combinations act as peripheral analgesics in a rat model of myofascial pain. Arch Oral Biol 2019;104: :33–9. 10.1016/j.archoralbio.2019.05.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Gregorio D, McLaughlin RJ, Posa L, et al. Cannabidiol modulates serotonergic transmission and reverses both allodynia and anxiety-like behavior in a model of neuropathic pain. Pain 2019;160:136–50. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sales AJ, Fogaça MV, Sartim AG, et al. Cannabidiol induces rapid and sustained antidepressant-like effects through increased BDNF signaling and synaptogenesis in the prefrontal cortex. Mol Neurobiol 2019;56:1070–81. 10.1007/s12035-018-1143-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Silote GP, Sartim A, Sales A, et al. Emerging evidence for the antidepressant effect of cannabidiol and the underlying molecular mechanisms. J Chem Neuroanat 2019;98: :104–16. 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kozela E, Pietr M, Juknat A, et al. Cannabinoids Delta(9)-tetrahydrocannabinol and cannabidiol differentially inhibit the lipopolysaccharide-activated NF-kappaB and interferon-beta/STAT proinflammatory pathways in BV-2 microglial cells. J Biol Chem 2010;285:1616–26. 10.1074/jbc.M109.069294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tervo-Clemmens B, Schmitt W, Wheeler G, et al. Cannabis use and sleep quality in daily life: a daily diary study of adults starting cannabis for health concerns. Medrxiv 2022. 10.1101/2022.01.19.22269565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;3:CD012182. 10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.National Academies of Sciences . The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. The National academies collection: reports funded by National Institutes of health. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yanes JA, McKinnell ZE, Reid MA, et al. Effects of cannabinoid administration for pain: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 2019;27:370–82. 10.1037/pha0000281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Meng H, Johnston B, Englesakis M, et al. Selective cannabinoids for chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Anesth Analg 2017;125:1638–52. 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Administration, F.a.D . What you need to know (and what we’re working to find out) about products containing cannabis or cannabis-derived compounds, Including CBD. FDA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang H-XB, Bean BP. Cannabidiol Inhibition of Murine Primary Nociceptors: Tight Binding to Slow Inactivated States of Nav1.8 Channels. J Neurosci 2021;41:6371–87. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3216-20.2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Xanthos DN, Sandkühler J. Neurogenic neuroinflammation: inflammatory CNS reactions in response to neuronal activity. Nat Rev Neurosci 2014;15:43–53. 10.1038/nrn3617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jamison RN, Edwards RR, Liu X, et al. Relationship of negative affect and outcome of an opioid therapy trial among low back pain patients. Pain Pract 2013;13:173–81. 10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00575.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Linton SJ. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine 2000;25:1148–56. 10.1097/00007632-200005010-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, et al. A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine 2002;27:E109–20. 10.1097/00007632-200203010-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wasan AD, Davar G, Jamison R. The association between negative affect and opioid analgesia in patients with discogenic low back pain. Pain 2005;117:450–61. 10.1016/j.pain.2005.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ogłodek E, Szota A, Just M, et al. The role of the neuroendocrine and immune systems in the pathogenesis of depression. Pharmacol Rep 2014;66:776–81. 10.1016/j.pharep.2014.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Pariante CM, Lightman SL. The HPA axis in major depression: classical theories and new developments. Trends Neurosci 2008;31:464–8. 10.1016/j.tins.2008.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bakunina N, Pariante CM, Zunszain PA. Immune mechanisms linked to depression via oxidative stress and neuroprogression. Immunology 2015;144:365–73. 10.1111/imm.12443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schnieder TP, Trencevska I, Rosoklija G, et al. Microglia of prefrontal white matter in suicide. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2014;73:880–90. 10.1097/NEN.0000000000000107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Albrecht DS, Kim M, Akeju O, et al. The neuroinflammatory component of negative affect in patients with chronic pain. Mol Psychiatry 2021;26:864–74. 10.1038/s41380-019-0433-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rosenblat JD, McIntyre RS. Efficacy and tolerability of minocycline for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. J Affect Disord 2018;227:219–25. 10.1016/j.jad.2017.10.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Köhler O, Benros ME, Nordentoft M, et al. Effect of anti-inflammatory treatment on depression, depressive symptoms, and adverse effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry 2014;71:1381–91. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Husain MI, Strawbridge R, Stokes PR, et al. Anti-Inflammatory treatments for mood disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychopharmacol 2017;31:1137–48. 10.1177/0269881117725711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brown AK, Fujita M, Fujimura Y, et al. Radiation dosimetry and biodistribution in monkey and man of 11C-PBR28: a PET radioligand to image inflammation. J Nucl Med 2007;48:2072–9. 10.2967/jnumed.107.044842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Owen DR, Yeo AJ, Gunn RN, et al. An 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) polymorphism explains differences in binding affinity of the PET radioligand PBR28. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2012;32:1–5. 10.1038/jcbfm.2011.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kreisl WC, Fujita M, Fujimura Y, et al. Comparison of [(11)C]-(R)-PK 11195 and [(11)C]PBR28, two radioligands for translocator protein (18 kDa) in human and monkey: Implications for positron emission tomographic imaging of this inflammation biomarker. Neuroimage 2010;49:2924–32. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.11.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Tan G, Jensen MP, Thornby JI, et al. Validation of the brief pain inventory for chronic nonmalignant pain. J Pain 2004;5:133–7. 10.1016/j.jpain.2003.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Knutson B, Westdorp A, Kaiser E, et al. Fmri visualization of brain activity during a monetary incentive delay task. Neuroimage 2000;12:20–7. 10.1006/nimg.2000.0593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kim M, Mawla I, Albrecht DS, et al. Striatal hypofunction as a neural correlate of mood alterations in chronic pain patients. Neuroimage 2020;211:116656. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Collect Data . Research Information Science & Computing, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc 1995;57:289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Albrecht DS, Normandin MD, Shcherbinin S, et al. Pseudoreference Regions for Glial Imaging with 11C-PBR28: Investigation in 2 Clinical Cohorts. J Nucl Med 2018;59:107–14. 10.2967/jnumed.116.178335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Buuren S. Flexible imputation of missing data. 2 ed. Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press, Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wamsley JK, Longlet LL, Hunt ME, et al. Characterization of the binding and comparison of the distribution of benzodiazepine receptors labeled with [3H]diazepam and [3H]alprazolam. Neuropsychopharmacology 1993;8:305–14. 10.1038/npp.1993.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kalk NJ. Are prescribed benzodiazepines likely to affect the availability of the 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO) in PET studies? synapse (New York, NY). 67, 2013: 909–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Canat X, Carayon P, Bouaboula M, et al. Distribution profile and properties of peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptors on human hemopoietic cells. Life Sci 1993;52:107–18. 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90293-C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Clow A, Glover V, Sandler M. Triazolam, an anomalous benzodiazepine receptor ligand: in vitro characterization of alprazolam and triazolam binding. J Neurochem 1985;45:621–5. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1985.tb04031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gehlert DR, Yamamura HI, Wamsley JK. Autoradiographic localization of ?peripheral-type? benzodiazepine binding sites in the rat brain, heart and kidney. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 1985;328:454–60. 10.1007/BF00692915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Harris CA, D'Eon JL, D’Eon JL. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory--second edition (BDI-II) in individuals with chronic pain. Pain 2008;137:609–22. 10.1016/j.pain.2007.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain Catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess 1995;7:524–32. 10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, et al. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin 2006;22:1911–20. 10.1185/030079906X132488 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The Oswestry disability index. Spine 2000;25:2940–53. 10.1097/00007632-200011150-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA 2014;311:1547–55. 10.1001/jama.2014.3266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Neubert T-A, Dusch M, Karst M, et al. Designing a tablet-based software APP for mapping bodily symptoms: usability evaluation and reproducibility analysis. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e127. 10.2196/mhealth.8409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hinchcliff M, Beaumont JL, Thavarajah K, et al. Validity of two new patient-reported outcome measures in systemic sclerosis: patient-reported outcomes measurement information system 29-item health profile and functional assessment of chronic illness Therapy-Dyspnea short form. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63:1620–8. 10.1002/acr.20591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, Monk TH, et al. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 1989;28:193–213. 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-063613supp001.pdf (3MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-063613supp002.pdf (13.7MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2022-063613supp003.pdf (64.4KB, pdf)