To the Editor:

Whipple disease is a rare multi-systemic disorder caused by Thropheryma whipplei, a Gram-positive bacillus. Gastrointestinal manifestations are the most frequent, but many other organs may be involved [1, 2]. Pulmonary hypertension (PH) associated with Whipple disease is extremely rare, and only a few isolated cases have been reported. We present two patients with PH-Whipple disease with a positive vasodilator test and excellent response to antibiotic therapy.

Patient 1

A 72-year-old Caucasian male with an 8-month history of intermittent abdominal pain and diarrhoea presented with dyspnoea on exertion that had progressed in the last 4 months (functional class III) and two-pillow orthopnoea to keep his head at 30°. He reported weight loss of 6 kg during the preceding 8 months. A colonoscopy performed 15 days before showed only nonspecific inflammation. Past medical history included mild chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treated with ipratropium. Physical examination revealed hypotension (systolic arterial pressure 90 mmHg) and bibasilar rales but not lower leg oedema. Laboratory data showed haemoglobin of 94 g·L−1 and albumin of 19 g·L−1. Antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor and a HIV test were negative. A chest computed tomography (CT) with embolism protocol demonstrated bilateral pleural and pericardial effusions and mediastinal adenopathy. No emboli were found in the pulmonary arteries. Abdominal CT showed mild ascites and multiple small lymph nodes. Gastroduodenoscopy demonstrated diffuse inflammation in the duodenum. Small bowel biopsies showed typical periodic acid–Schiff (PAS)-positive diastase-resistant histiocytes. Several days later PCR confirmed the presence of T. whipplei. Transthoracic echocardiography showed normal left cavities with a dilated right ventricle (55 mm). The velocity of the tricuspid jet was 3.68 m·s−1 with an estimated systolic pulmonary artery pressure (sPAP) of 64 mmHg. A ventilation/perfusion scan excluded thromboembolic disease. Right heart catheterisation confirmed the diagnosis of PH (table 1). A vasodilator test with epoprostenol revealed a positive response with a 12 mmHg decrease of mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) and ∼1 L·m−1·m−2 increase of cardiac index. A 4-week course of 2 g ceftriaxone per 24 h was started followed by trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800 μg. 2 months later the patient was much better (functional class I) with N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) 288 pg·mL−1. An echocardiogram was performed with near normal values (right ventricle 36 mm) and minimal tricuspid insufficiency. After 10 months of treatment all symptoms resolved and a new echocardiogram was normal.

Table 1. Haemodynamic studies of the two patients pre- and post-vasodilator testing.

| dPAP mmHg | mPAP mmHg | sPAP mmHg | PCWP# mmHg | CI L·m−1·m−2 | PVR Wood unit | |

| Pre-vasodilator test | ||||||

| Case 1 | 29 | 34 | 47 | 10 | 2.05 | 6.7 |

| Case 2 | 33 | 52 | 87 | 14 | 2.3 | 7.91 |

| Post-vasodilator test | ||||||

| Case 1 | 20 | 25 | 34 | 9 | 3.1 | 3.9 |

| Case 2 | 23 | 39 | 65 | 12 | 3.8 | 3.1 |

dPAP: diastolic pulmonary arterial pressure; mPAP: mean pulmonary artery pressure; sPAP systolic pulmonary artery pressure; PCWP: pulmonary capillary wedge pressure; CI: cardiac index; PVR pulmonary vascular resistance. #: both patients showed PCWP within normal limits.

Patient 2

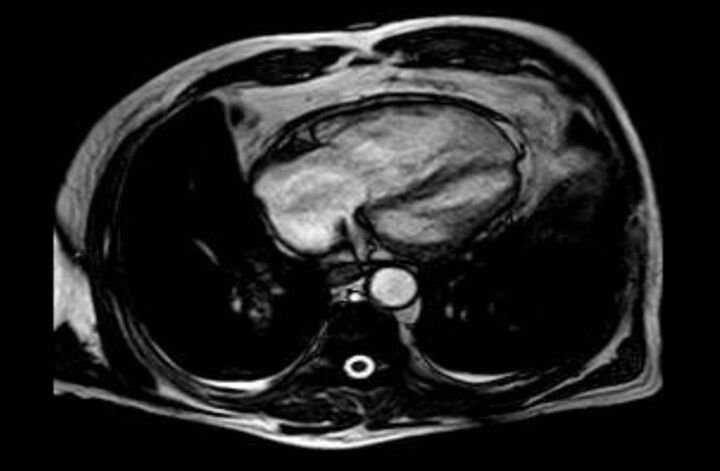

A 66-year-old Caucasian male doctor was admitted with worsening dyspnoea and near-syncope. He had been a mild smoker 20 years previously and showed moderate airflow obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 s 52%), which was treated with tiotropium. In the previous year he had received several courses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prednisone because of spinal and polyarticular pain. 2 months before admission he had complained of diarrhoea but a colonoscopy showed no abnormalities. Physical examination revealed a sPAP of 95 mmHg and bilateral pretibial oedema. A CT scan showed pulmonary artery dilatation with no evidence of emboli. A ventilation/perfusion scan ruled out pulmonary embolism. Laboratory data showed anaemia and increased levels of NT-proBNP (5640 pg·mL−1). Tests for antinuclear antibodies and HIV serology were negative. Gastroscopy revealed diffusely erithematous antral mucosa. Duodenal biopsies and PCR for T. whipplei confirmed the diagnosis of Whipple disease. Transthoracic echocardiography showed a dilated right ventricle (53 mm) with an estimated sPAP of 112 mmHg. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a right ventricle of 87x53 mm with an ejection fraction of 53% and normal left cavities (fig. 1). Right heart catheterisation confirmed PH (table 1), with a positive response to epoprostenol (mPAP decrease of 13 mmHg, cardiac index increase >2 L·m−1·m−2). Because biopsy results were not known at the time of catheterisation, the patient was initially treated with amlodipine 20 mg·day−1. 7 days later he was admitted to the hospital with dyspnoea at rest, sPAP 85 mmHg and oxygen saturation 89%. Chest radiography showed bilateral pleural effusion. Owing to the high suspicion of PH-Whipple disease, 2 g of ceftriaxone every 24 h was started. After 10 days of treatment, with confirmed diagnosis, a significant improvement was noted. Oxygen saturation at rest was 96%. Echocardiography demonstrated a reduction in sPAP (estimated 61 mmHg). Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160/800 μg was started after 2 weeks of ceftriaxone. Amlodipine was discontinued 3 months later. 6 months after starting antibiotics the patient was in functional class I, with an estimated sPAP of 41 mmHg and NT-proBNP of 244 pg·mL−1.

Figure 1.

Magnetic resonance image from patient 2 showing marked enlargement of right cardiac chambers.

Discussion

The first description of Whipple disease was reported in 1907 by George Whipple. The causative agent of this disease is T. whipplei, a Gram-positive Actinobacterium. In 1991, a PCR assay was developed providing an excellent tool for the diagnosis of the disease [3]. Infection occurs via the gastrointestinal route with intensive macrophage recruitment and activation. It predominantly occurs in males (8:1 male-to-female ratio). As in other inflammatory diseases, genetic susceptibility probably plays an important role. A defect in cellular immune response may predispose to infection and might explain the rarity of the disorder despite the ubiquitous presence of T. whipplei, but the immunological defect is, in some way, probably specific to this pathogen since other infections do not occur more frequently. Humoral response does not appear to be affected, with normal levels of IgG and IgM. Moreover, the impaired immunity is probably also increased by the presence of T. whipplei. Macrophages from patients with Whipple disease have a lower ability to phagocytosis and expression of CD11b in circulating cells, a receptor that facilitates cell adhesion, is very low [4]. One of the main features is decreased production of interleukin (IL)-12, a typical cytokine of activated macrophages that is key in T-helper 1 differentiation and, therefore, interferon-γ production [5]. There is also reduced secretion of IL-1, IL-6 and IL-10, but the production of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is increased. The TGF-β pathway has been shown to be a key role in the development of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Apoptosis of macrophages is another critical event in the pathogenesis of Whipple disease, which seems to be induced by intracellular T. whipplei and may explain the dissemination of the pathogen [6]. These inflammatory changes in the pulmonary arteries and venules are perhaps the basis of the increased pulmonary vascular pressure.

Symptoms are nonspecific but the most typical are arthralgia, diarrhoea, abdominal pain and weight loss, but cardiac and central nervous system involvement may occur. Diagnosis is based on duodenal biopsy with the presence of PAS-positive histiocytes and direct testing for bacterial DNA by PCR. Current treatment consists of ceftriaxone for 2–4 weeks followed by trimethoprim/sulfametoxazole for at least 1 year.

Pulmonary involvement by Whipple disease is not well defined but perhaps is not uncommon, while PH-Whipple disease is extremely rare. The two cases that were first reported were secondary to aortic insufficiency, probably related to endocarditis caused by T. whipplei [7, 8]. Another five cases have been reported [9–13], two of them with haemodynamic studies and only one with vasodilator testing. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure was normal in our patients but nevertheless we cannot exclude capillary venous involvement. The underlying pathogenic mechanism of PH in Whipple disease has not been clearly established but complete resolution with antibiotics, as presented in our cases, is the strongest evidence for a causal relationship. Pleural biopsies from one patient with confirmed PH-Whipple disease demonstrated subpleural pulmonary arteries with partial luminal obliteration by PAS-positive macrophages and fibrinoid debris [11]. This inflammatory nature of PH-Whipple disease may explain the dramatic response of PH to antibiotic therapy. It is noteworthy that a Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction has been described in one patient, probably related to the strong effect of antibiotics [10]. Another important aspect is the positive response to vasodilator testing in our patients and in the other cases reported previously, as well as the poor results with calcium blockers. One of our patients was initially treated with amlodipine according to the results of vasodilator testing but no significant response was achieved. Similar results were seen in the patient reported by Najm et al. [12] treated with sildenafil and nifedipine, with minimal early improvement but severe worsening a few months later. We did not perform right heart catheterisation during follow-up due to the excellent outcome of our patients, although it would be very interesting to know if they had normalised haemodynamic values. In both cases, the serial echocardiograms showed progressive improvement and were virtually normal after 10 and 6 months of antibiotic treatment, respectively.

In conclusion, we reported two patients with PH-Whipple disease, an extremely rare association, both with positive vasodilator testing and complete resolution of PH shortly after antibiotic treatment. These results suggest an inflammatory nature of PH and add evidence to causal relationships with Whipple disease. Vasodilators seem to have little efficacy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside the online version of this article at err.ersjournals.com

References

- 1.Marth T, Raoult D. Whipple’s disease. Lancet 2003; 361: 239–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnol CA, Moreira RK, Lam-Himlin D, et al. Whipple disease a century after the initial description. Am J Surg Pathol 2012; 36: 1066–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Relman DA, Schmidt TM, MacDermott RP, et al. Identification of the uncultured bacillus of Whipple’s disease. N Eng J Med 1992; 327: 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marth T, Roux M, von Herbay A, et al. Persistent reduction of complement receptor 3-α-chain expressing mononuclear blood cells and transient inhibitory serum factors in Whipple’s disease. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 1994; 72: 217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marth T, Neurath M, Cuccherini BA, et al. Defects of monocyte interleukin 12 production and humoral immunity in Whipple’s disease. Gastroenterology 1997; 113: 442–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desnues B, Ihrig M, Raoult D, et al. Whipple’s disease: a macrophage disease. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2006; 13: 170–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bostwick DG, Bensch KG, Burke JS, et al. Whipple’s disease presenting as aortic insufficiency. N Engl J Med 1981; 305: 995–998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morrison DA, Gay RG, Feldshon D, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension in a patient with Whipple’s disease. Am J Med 1985; 79: 263–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Riemer H, Hainz R, Stain C, et al. Severe pulmonary hypertension reversed by antibiotics in a patient with Whipple’s disease. Thorax 1997; 52: 1014–1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peschard S, Brinkane A, Bergheul S, et al. Maladie de Whipple associée a une hypertension artérielle pulmonaire. Réaction de Jarisch–Herxheimer après antibiothérapie [Whipple disease associated with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Jarisch–Herxheimer reaction after antibiotic therapy]. Presse Med 2001; 30: 1549–1551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyle PL, Weber RD, Bogarin J, et al. Reversible pulmonary hypertension in Whipple disease: a case report with clinicopathological implications, and literature review. BMJ Case Rep 2009. [In press DOI: 10.1136/bcr.06.2008.0095]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Najm S, Hajjar J, Nelson RP Jr, et al. Whipple’s disease-associated pulmonary hypertension with positive vasodilator response despite severe hemodynamic derangements. Can Respir J 2011; 18: e70–e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoskote SS, Georgescu A, Ganjhu L, et al. Resolution of Whipple disease-induced pulmonary hypertension following antibiotic therapy. Am J Ther 2014; 21: e143–e147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.