Abstract

The transformation of free state organic micro-pollutants (MPs) has been widely studied; however, few studies have focused on mixed and bound states MPs, even though numerous ionizable organic MPs process a strong tendency to combine with dissolved organic matters in aquatic environments. This study systemically investigated the distribution and toxicity assessment of tetracycline (TET) transformation products in free, mixed and bound states during UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes. A total of 33 major transformation products were identified by UPLC-Q-TOF-MSMS analysis, combining the double bond equivalence and aromaticity index calculations. The binding interaction would weaken the attack on the dimethylamino (-N(CH3)2) group and induce the direct destruction of rings A and B of TET through the analysis of 2D Kernel Density changes and density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Toxicity assessment and statistics revealed that the intermediate products with medium molecular weight (230≤ m/z ≤ 380) exhibited higher toxicity, which was closely related to the number of the rings in molecular structures (followed as 2»3 > 1≈4). A predicted toxicity accumulation model (PTAM) was established to evaluate the overall toxicity changes during various oxidation processes. This finding provides new insight into the fate of bound MPs during various oxidation processes in the natural water matrix.

Keywords: Binding interaction, Tetracycline, Humic acid, Transformation products, Toxicity assessment

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Total 33 oxidation products varied with TET in free, mixed and bound states.

-

•

Binding interaction regularly changed TET degradation pathway during various AOPs.

-

•

The binding effect would induce the direct destruction of rings A and B of TET.

-

•

Ring number of product structures related to toxicity index fallowed as 2 » 3 > 1≈4.

-

•

Proposed PTAM model verified that the products of bound TET were more toxic.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, due to the effects of effectively killing pathogens in animals and promoting the growth of livestock and poultry, antibiotics have been commonly used in medical, biological science research, agriculture, animal husbandry and food industry [1,2]. However, antibiotics have been widely detected in groundwater, surface water, sediment and soil, and the residual concentrations reach up to mg/L level [[3], [4], [5]], even the situation is increasingly deteriorating due to lower enzymatic degradation rate and the limited efficiency of the conventional treatment in hospital wastewater treatment facilities and sewage plants [6,7]. The ecotoxicity and related derivative drug resistance induced by long-term exposure to antibiotics have received increasing attention [8]. As one of the various antibiotics, the production and usage of tetracycline (TET) rank second worldwide. The residual TET has also been detected in milk samples [9], and the drug-resistant genes may accumulate and biomagnify through the food chain [10], which poses a great potential threat to human health.

The formation of various TET species (including TET+, TET±, TET− and TET2−) are governed by the respective ionization constants (pKa1 = 3.3, pKa2 = 7.7, pKa3 = 9.7) [1,11]. Additionally, due to the characteristic four-ring structure of TET with multiple functional substituents of N- and O-groups, TET poses a strong tendency to complex with dissolved organic matters (DOM) and metal ions [12], which has a greater impact on the migration, transformation and degradation of TET in the aquatic environment [13,14]. DOM would promote the oxidation of residual organic contaminants in natural water environment during direct and indirect photolysis processes acting as the photosensitizer to accelerate the generation of ·OH and O2−· [[15], [16], [17]], or inhibit the degradation acting as a reactive oxidation species (ROSs) competitor during the advanced oxidation processes (AOPs) [10,18].

Various AOPs have been applied to the degradation of antibiotic wastewater, including photocatalytic oxidation, free radical oxidation, and non-radical oxidation technologies, which show significant oxidation performance [1,19,20]. However, most of the existing studies mainly focus on the transformation of free state antibiotics [[21], [22], [23], [24]], while the residual antibiotics in natural water environments are a mixed state (mixed with DOMs) and a bound state (bound with DOMs), due to that the various DOMs would quickly combine with them [25]. Furthermore, given that the TET antibiotics are nitrogen-containing organic pollutants, there is also a potential risk of producing carcinogenic nitrogen-containing disinfection by-products during the oxidation and disinfection process of water sources, especially in the presence of DOM [26,27]. Our previous work has proved that the binding effect of humic acid (HA) has a great influence on the degradation of TET by various oxidation processes, and the results indicated the bound TET showed stronger inertia compared to free TET during the UV, UV/H2O2 and UV/PMS processes [11]. However, the effect of binding interaction on TET degradation pathways and intermediate products has not been concerned yet. Besides, compared with the free TET degradation, the changes in toxicity of the transformation products of bound TET under different oxidation processes, as well as the impact mechanism of the binding interaction, also need to be investigated urgently.

Based on the above considerations, this study was devoted to systematically investigate the distribution of transformation products and degradation pathway of TET in free, mixed and bound states during various reaction oxidation processes, including UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes. The transformation products during four oxidation processes were identified by ultra-HPLC-quadrupole-time-of-flight-mass/mass spectrometry (UPLC-Q-TOF-MS/MS) analysis, and the changes of relative concentration were monitored over time. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations and the comparison of 2D Kernel Density of N elements were adopted to reveal the mechanism of binding effect on the degradation pathway. Besides, the toxicity of transformation products was estimated by the Ecological Structure-Activity Relationship (ECOSAR) program, and a predicted toxicity accumulation model (PTAM) was established to evaluate the toxicity changes over time during different oxidation processes.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Humic acid (HA), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 30% v/v) and persulfate (PS) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Tetracycline was supplied from TCI (Shanghai) Development Co., Ltd. l-histidine (LH), sodium azide (NaN3), Methyl alcohol (MA) and tert-butyl alcohol (TBA) were obtained from Aladdin Industrial Corporation. Sodium thiosulfate, nitric acid, and sodium hydroxide were purchased from Kelong Chemical Co. Ltd (Chengdu, China). Commercial multi-walled carbon nanotubes (CNTs, diameter is 10–20 nm and length is 10–30 μm) were obtained from Chengdu Organic Chemicals Co., Ltd (Chengdu, China) [28]. Formic acid and acetonitrile were high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grades for TET analysis. All the other reagents were analytic grade, and all solutions were prepared with deionized (DI) water.

2.2. Experimental procedure

All the oxidation experiments were conducted in 200 mL quartz reactors in triplicate using magnetic stirrers at 25 °C. The TET was oxidized in three states, including free state (only exist TET in the reaction solution), mixed state (mix HA and TET in the reaction solution before reaction) and bound state (combine HA and TET to binding equilibrate for 12 h in the reaction solution before the reaction, based on our previous research) [11]. The higher initial concentration (20 μM) of TET than in real water was used to detect the transformation products. The concentration of H2O2, PS and CNTs were 200 μM, 100 μM and 0.05 g/L for the UV/H2O2, UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes, respectively. The UV/H2O2 and UV/PS processes were started after the addition of oxidants under the 254 nm UV light (30 W low-pressure mercury lamp), while the CNTs/PS process was started after the addition of PS and CNTs. To monitor the concentration of TET and transformation products, 1 ml of the samples were collected from the reactor quenched with 15 μL 1 M sodium thiosulfate at each time interval, and the sample of CNTs/PS process was filtered with a 0.22 μm filter to remove CNTs before quenched with sodium thiosulfate.

2.3. Analytic methods

The concentration of TET was measured by an HPLC system (Waters e2695), equipped with a UV–visible detection (Waters 2489) at 355 nm and a Waters Symmetry C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm) at the column temperature of 35 °C. The mobile phase consisted of 20 mM H3PO4 (80%) and acetonitrile (20%) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

The transformation products of TET were identified by UPLC-Q-TOF-MSMS (AB Sciex, USA) in negative mode. A water Acquity BEH C18 column (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm) was used for chromatographic separation, and the temperature was set at 35 °C. The mobile phase of the UPLC consisted of 0.1% formic acid water (A) and acetonitrile (B), with a gradient elution of A/B from 90/10 (v/v) to 10/90 in 7 min, and maintained for 3 min, and then decreased back to 90/10 in the next 2 min and finally kept for 1min. The injection volume and flow rate were 20 μL and 0.3 mL/min, respectively. The operating conditions of Q-TOF-MS in electrospray ionization (ESI) negative mode were: sampling cone 35 V, capillary 2.0 kV, source temperature 120 °C, desolvation temperature 350 °C, cone gas flow 40 L/h, desolvation gas flow 900 L/h, and trap MSMS collision energy ramp 10–40 eV. Data acquisition was analyzed by Agilent Masshunter Qualitative Analysis (v 10.0) software to analyze the molecular formulas, and the values of H/C and O/C were calculated based on molecular formulas [20]. The 2D Kernel Density distribution based on the number of nitrogen atoms in the molecular formula was calculated via the Origin 2019b.

2.4. Theoretical calculation

In this work, the Gaussian 09 program was applied to perform the theoretical density functional theory (DFT) calculation at the B3LYP/6-311 + G(d) level [20]. The energies of TET were calculated with the solvation model of density (SMD) continuum solvation model, and the polarized continuum model (PCM) was used to take care of the effect of bulk solvent effect [29]. The theoretical parameters obtained from the Gaussian out files were used to calculate the natural population analysis (NPA) charge distribution, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) and the Fukui index (f0), which could further assess the vulnerable sites of TET molecule.

2.5. Toxicity assessment

In this work, the acute (EC50 values) and chronic toxicities (LC50 values) of TET and its transformation products to three different trophic levels aquatic organisms, including green algae, daphnia, and fish were estimated based on the Ecological Structure Activity Relationship (ECOSAR) program and the Toxicity Estimation Software Tool (T.E.S.T.), based on the Quantitative Structure Activity Relationships (QSAR) [30,31].

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Comparison of TET oxidation in different oxidation systems

The oxidations of TET in three states (including free state, mixed state, and bound state) by UV, PS, CNTs, UV/H2O2, UV/PS, and CNTs/PS processes were depicted in Fig. S1. As seen from Fig. S1a, both free and mixed TET were degraded only about 10% in UV process, but the degradation of bound TET was slightly inhibited. The rates of free, mixed and bound TET degradation were about 25%, 17% and 13% in the single PS process (Fig. S1b), respectively, while the states of TET in solution do not affect the adsorption of CNTs (Fig. S1c). As for the UV/H2O2 process, the degradation of the single TET was up to 90%, while the removal rates of both mixed and bound TET were only about 60% due to the influence of HA (Fig. S1d). As shown in Fig. S1e-S1f and Fig. S2b, the oxidation performance of UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes increased greatly with the activation of UV and CNTs, compared to the single PS process, both TET degradation and PS decomposition were accelerated. And the oxidation tendencies for different states TET in UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes were in the order: free state » mixed state > bound state.

To get insights into the reactive oxidation species of UV/H2O2, UV/PS, and CNTs/PS processes, methyl alcohol MA (kMA,·OH = 9.7 × 108 M−1 s−1, kMA,·SO4− = 3.2 × 106 M−1 s−1) and tert-butyl alcohol TBA (kTBA,·OH = 6 × 108 M−1 s−1) were employed as scavengers of ·OH/·SO4− and ·OH [[32], [33], [34]], respectively, while the l-histidine LH (kLH,1O2 = 0.4–1 × 108 M−1 s−1) and sodium azide NaN3 (kNaN3, 1O2 = 1 × 109 M−1 s−1) were adopted as the specific probes of singlet oxygen (1O2) [35,36]. Of note, the degradation of TET was significantly inhibited in the presence of MA and TBA in UV/H2O2 processes, indicating that the ·OH was identified as the main contributor to TET degradation (Fig. S3a). Given that the removal rates of TET were decreased from 82% to 62% and 54% with the addition of TBA and MA in UV/PS process, both ·OH and ·SO4− were involved in the TET degradation (Fig. S3b). Nevertheless, different from UV/H2O2 and UV/PS processes, a negligible effect was observed in the presence of TBA or MA in CNTs/PS process, suggesting that a non-radical oxidation pathway was performed in CNTs/PS process. Based on our previous study [35], 1O2 was considered for non-radical processes, and the LH and NaN3 were adopted as the specific probes to further confirm the existence and role of 1O2 in the oxidation process. Significant inhibition of TET removal was observed in the presence LH and NaN3 (Fig. S3c), implying that 1O2 was certainly be generated by CNTs/PS process. Given the difference of ROSs in UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes, the four oxidation processes were selected to further analyze the transformation pathways, products and toxicity of TET in three states.

3.2. Molecular component characterization of all transfer products

The oxidations of HA in UV, UV/H2O2 and UV/PS were insignificant based on the UV absorption spectrum analysis, and while the intensity of UV254 of HA dropped from 0.18 a.u. to 0.08 a.u. in CNTs/PS process mainly due to the absorption of CNTs (Fig. S4). Due to the lower oxidation of HA during the oxidation process, most of the products detected in the TET degradation by the four oxidation experiments are the intermediate products of TET.

To evaluate the changes of TET degradation products in different states at the molecular level, the van Krevelen diagrams were applied to investigate the distribution of the intermediate products of TET, referring to Lv's study [37]. Based on the element ratios of H/C and O/C, all the intermediate products distributed in the van Krevelen diagram were divided into four quadrants with TET as the coordinate origin. Compared to TET molecules, molecules of intermediate products located in quadrant I (H/C rises, O/C rises) indicated that the oxidation process was mainly due to hydroxyl or oxygen addition leading to double bond destruction or ring-opening; quadrant II (H/C rises, O/C falls) showed that degradation process was mainly hydrogenation with double bond addition or ring-opening, and dehydroxylation; quadrant III (H/C falls, O/C falls) demonstrated that degradation process was mainly elimination reaction to generate double bonds; quadrant IV (H/C falls, O/C rises) cleared that degradation process was mainly hydroxyl substitution or addition to form a carbonyl group. As illustrated in Fig. 1, after the oxidation of TET in free, mixed and bound states by UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes, the intermediate products were mainly located in quadrants I and IV, and the percentages of the number of molecules in these two quadrants were counted in Fig. 1a–p. It can be seen in UV-based processes, the percentages in quadrant I of mixed TET transformation products decreased compared to free TET, which might be owing to HA inhibited the UV pyrolysis, and the substitution of free radicals played a major role so that the change of the percentage in quadrant I was relatively small in the CNTs/PS process. By comparing the percentage changes of the mixed and bound TET to insight the role of binding, it can be concluded that the percentage in quadrant I of bound TET transformation products increased in all the processes, revealing that the binding interaction contributed to the addition of ROSs, and weakened the effect of UV cracking simultaneously. Additionally, the diversity of degradation products could also be inferred from the polymerization degree of the data points. By comparing the size of the 95% confidence circle in van Krevelen diagrams, the diversity of the bound transformation products were the smallest except for the UV process, which was also in line with the phenomenon of Fig. S1a.

Fig. 1.

Van Krevelen diagrams of transformation products of TET in free, mixed and bound states after (a)–(d) UV, (e)–(h) UV/H2O2, (i)–(l) UV/PS and (m)–(p) CNTs/PS processes ([HA] = 3 mg/L, [TET] = 20 μM, [H2O2] = 200 μM, [PS] = 100 μM, [CNTs] = 0.05 g/L, pH 6.5).

3.3. Product distribution and structure identification

To avoid the influence of the detection background on the transformation products analysis, the intensity of each peak (m/z) in the mass spectrum had been subjected to background subtraction, and these peaks with relative intensity >200 were selected for further transformation products analysis. As shown in Fig. S5-S7, a total of 33 major transformation products (m/z) of TET in free, mixed and bound states were identified. The molecular formulas of the 33 transformation products were calculated via Formula Calculator software based on that the mass error was <5 ppm [37]. By combining isotope distribution, MSMS spectrometry fragments, double bond equivalence (DBE, characterization of the number of double bonds and rings in a molecule) (Text S1) and aromaticity index analysis (AI, characterization of molecular aromaticity index) (Table S1) [38,39], the structural formulas were further identified in Fig. S8-S11.

Fig. 2 shows the relative concentration heat map of transformation products in different oxidation processes in 60 min. It can be concluded that the numbers of transformation products in UV (amount of products: 7) and UV/H2O2 (7) processes were less than UV/PS (14) and CNTs/PS (15) processes, which was attributed to the oxidation performance of different systems and the selective oxidation of ROSs [29,40]. For both UV and UV/H2O2 processes (Fig. 2a and b), the mixing and binding between HA and TET would result in a reduction in the number of transformation products and the formation of small molecular products, such as m/z = 292.8 and 182.8 in UV process, and m/z = 245.0 and 182.8 in UV/H2O2 process. After the treatment by UV/PS process (Fig. 2c), there were no differences in the types of TET transformation products in free, mixed and bound states, but it was worth noting that compared with free TET, the cumulative concentration part of molecules (such as m/z = 198.8, 201.0, 243.0 and 245.0) produced by mixed and bound TET had increased significantly. In terms of CNTs/PS process (Fig. 2d), the concentration of several products like m/z = 431.1, 406.1, 374.1, 351.0 and 319.0 gradually decreased, while products like m/z = 255.0, 245.0 and 201.0 gradually increased with this sequence: free TET → mixed TET → bound TET. Based on the above analysis, it can be concluded that the mixing and binding interaction between TET and HA would cause the rapid formation of certain small molecule transformation products (m/z = 182.8, 201.0, 243.0, 245.0 and 225.0) during the oxidation of TET.

Fig. 2.

Relative concentration heat maps of transformation products of TET in free, mixed and bound states after (a) UV, (b) UV/H2O2, (c) UV/PS and (d) CNTs/PS processes ([HA] = 3 mg/L, [TET] = 20 μM, [H2O2] = 200 μM, [PS] = 100 μM, [CNTs] = 0.05 g/L, pH 6.5).

3.4. Elucidation of transformation pathways

To probe the mechanism of binding effect on the changes of TET transformation products, the degradation pathways of TET during UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS, and CNTs/PS processes were further investigated, respectively. The density functional theory (DFT) was adopted to calculate the Fukui index (f0) representing radical attack, the natural population analysis (NPA) charge distribution, the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO), and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO), which were further applied to access the vulnerable sites of TET [41,42]. Fig. 3a showed the Fukui index (f0) distribution of tetracycline atomic points, and it was divided into four levels, including easy, medium, minor difficult and difficult levels, reflecting the degree of difficulty of free radicals attack sites [43]. C27, C26, C30, C22, O5 and O3 were the relatively vulnerable sites by free radicals (·OH and ·SO4−) based on the Fukui index. The LUMO and HOMO energy of TET were estimated to be −0.079 eV and −0.209 eV, respectively, and the π∗ antibonding and π-bonding orbitals located on the benzene ring D and the –N(CH3)2 group, meeting the results of Fukui index analysis. Fig. 3b reflected the charge distribution of each atom of TET based on the theoretical natural population analysis (NPA), indicating that sites of C32, C14, C31, and C12 concentrating negative charge were more susceptible to electrophilic attacks during non-radical processes.

Fig. 3.

The visualized Fukui index (a), and the charges of TET atoms (b) (the HOMO and LUMO frontier orbitals of TET were located at the bottom left and upper right in Fig. 3b inset); The yellow columns represent C atoms, the blue columns represent O atoms, and the purple columns represent N atoms.

Combining results of the DFT calculation and the changes in the relative intensity of the transformed products, the transformation pathways of TET in UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS, and CNTs/PS processes were proposed. Fig. S12 demonstrated that C26/C27 of TET in the free state would be attacked firstly to generate the product (m/z = 427.1), and the sites of C24 and O2 were further removed to form a carbon-carbon double bond, accompanied by ring A cracking (m/z = 287.1 and 315.1) during UV cracking process. However, under the influence of the binding interaction, the degradation of TET was more prone to the cleavage between the B ring and the A ring (m/z = 182.8 and 292.8). Similar to prior studies [20,44,45], the substitution of ·OH and elimination of UV occurred at the position of –N(CH3)2 and C24/O2 due to the simultaneous effect of both UV and ·OH during the UV/H2O2 process (Fig. S13). Then, the C22 site was attacked, resulting in the cleavage of A ring (m/z = 315.1). Of note, the cleavage between the B ring and the A ring of bound TET state was promoted compare to free TET. As for the UV/PS process (Fig. S14), since the ·SO4− was also involved in oxidation reaction except for UV and ·OH, the oxidation performance had been significantly improved. Except for the pathways of substitution reaction and UV elimination, C32 was directly attacked to cause ring B to crack. Furthermore, the products of ring cracking influenced by binding interaction would be further oxidized. The group of –N(CH3)2 was attacked as the first target site of free TET during CNTs/PS process [8], and the sites of C32 followed due to the larger negative charge density based on the charge distribution of TET atoms (Fig. S15). The site of C12 and hydroxyl group were further oxidized, leading to the cleavage of ring B and ring C. However, molecular cleavage has the same effect as the UV/PS process under the influence of binding interaction. The overall reaction pathways of TET in both free and bound states during four oxidation processes were summarized in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The overall reaction pathways of TET in UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS and (d) CNTs/PS processes ([HA] = 3 mg/L, [TET] = 20 μM, [H2O2] = 200 μM, [PS] = 100 μM, [CNTs] = 0.05 g/L, initial pH 6.5).

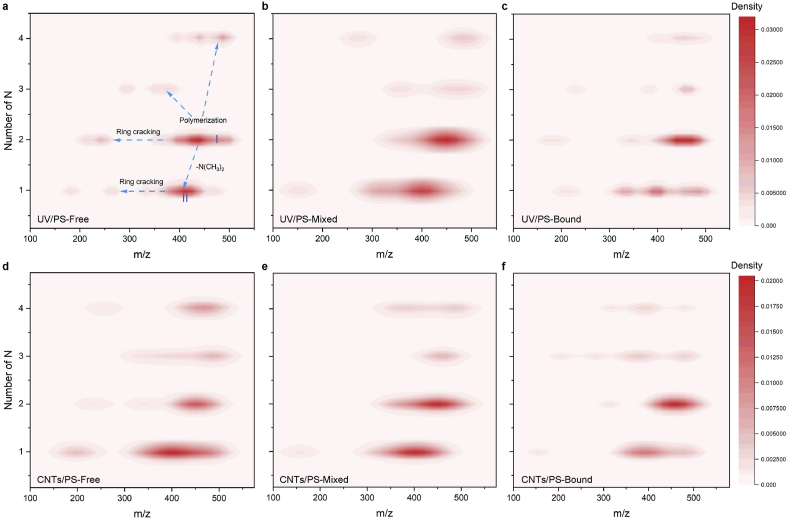

3.5. Effect of binding interaction on transformation products

Given that the –N(CH3)2 group was the most vulnerable site of TET, and it had been identified as the critical group of TET involved in binding interaction with HA in the previous study [11], the nitrogen contents of transformation products were adopted as a probe to reveal the mechanism of binding interaction on the transformation pathways of TET oxidation. Fig. S16 reflected that the proportion of transformation molecules containing N elements decreased significantly after the binding effect during UV/H2O2, UV/PS and CNTs/PS. Additionally, the 2D Kernel Density distribution around m/z = 443.1 containing 2 N atoms was attributed to the pristine TET molecules (area I), and located at around m/z = 402.1 containing 1 N atoms was ascribed to the elimination of the –N(CH3)2 group in the TET molecules (area II), while the role of ring cracking in TET molecule and transformation products resulted in a change in m/z but a constant number of N atoms (Fig. 5). Besides, a small number of product molecules would also polymerize, leading to the increase of N atoms content. Fig. S17 was the 2D Kernel Density distribution of nitrogen-containing molecules during UV and UV/H2O2 processes. The migration trajectory of nitrogen-containing molecules indicated that the –N(CH3)2 group of TET in a free state was most vulnerable to attack [45,46], which agreed with the results of the DFT calculation. In UV/PS process (Fig. 5a-c), the density of area I/II was 0.028/0.026 in the free TET system, compared with 0.031/0.027 in the mixed TET system, while 0.030/0.018 was observed in the bound TET system in UV/PS process. The ratio of area II/area I was decreased from 92.9% to 87% under the mixed condition with HA, but it was significantly decreased to 60% in the bound TET system caused by binding interaction. As for CNTs/PS process (Fig. 5d-e), the density of area II influence by binding interaction decreased from 0.020 to 0.012.

Fig. 5.

The 2D Kernel Density distribution of nitrogen-containing molecules after UV/PS (a), (b), (c) and CNTs/PS processes (d), (e), (f) ([HA] mg/L, [TET] = 20 μM, [PS] = 100 μM, [CNTs] = 0.05 g/L, initial pH 6.5).

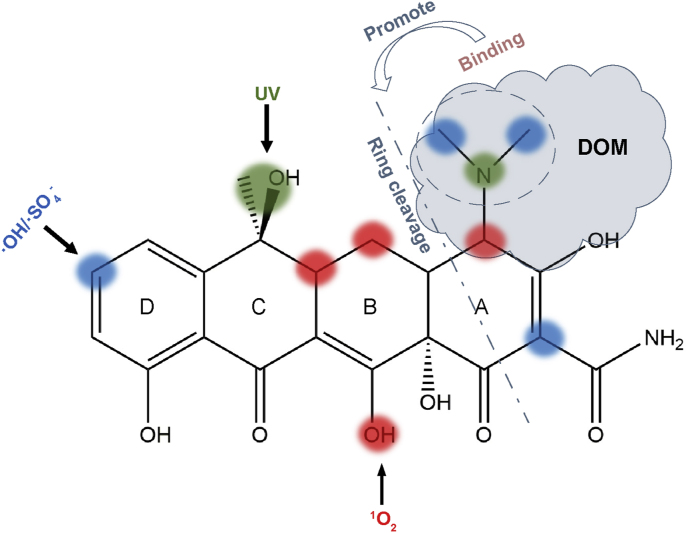

Summing up the above results, the sites of C26, C27 and N9 were common vulnerable sites of UV pyrolysis, free radicals (·OH and ·SO4−) and non-radical (1O2). Additionally, the UV elimination of methyl and hydroxyl (located at C24 and O2) induced the formation of the carbon-carbon double bond between C15 and C12. Substitution and the cleavage of the D ring started at sites of C22 constituted the attack routes of free radicals, while the C32, C12 and O3 were the important target sites of 1O2, which induced the cleavage of the ring C and ring B. However, it is noteworthy that the binding interaction between –N(CH3)2 group of TET and HA would promote the generation of small molecules (m/z = 317.1, 287.1) due to the direct cleavage of the ring A, which might be attributed to that the electron density shift caused by the binding weakened the attack of –N(CH3)2 group and its nearby sites (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

The proposed mechanism of binding effect on TET degradation pathway.

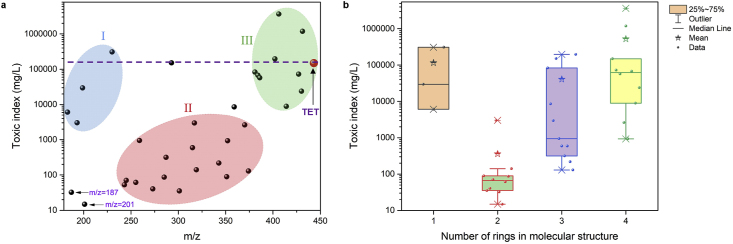

3.6. Toxicity assessment

To further unveil the toxic responses of TET and its 33 transformation products on various aquatic organisms (i.e., fish, daphnid, and green algae), the acute (LC50, half lethal concentration after 96 h or 48 h of exposure) and chronic toxicities (ChV) of TET and its 33 transformation products were predicted by the Ecological Structure Activity Relationship (ECOSAR) program (version 2.0) [35,47], and the class-specific values of LC50 and ChV were listed in Table S2. As shown, more than 88% of intermediate products showed much higher toxicity than parent TET, similar to the results of the previous study [20]. Of note, the toxic of transformation products were mainly concentrated in three areas (area I: 180≤ m/z ≤ 230, area II: 230≤ m/z ≤ 380, area III: 380≤ m/z ≤ 450) according to different molecular weights, and the toxic index in three areas exhibited area II » area I > area III except for two special products (m/z = 201.1 and 187.0), reflecting that TET was firstly oxidized into more toxic medium molecular weight products, and then the toxicity decreased due to further oxidation into small molecules (Fig. 7a). To further probe the mechanism of the product's toxicity distribution, statistics on the toxicity and the number of rings in the structure of the transform products were carried out. As illustrated in Fig. 7b, the toxicity of molecules with 2 rings in product structure was the most toxic, followed by molecules with 3 rings, while the molecules with 4 and 1 rings in product structure were relatively lower [48]. Since the structure of products (m/z = 201.1 and 187.0) contained 2 rings, the higher toxicity of them could be well explained. Based on the above analysis, it could be concluded that the toxicity distribution of TET transformation products first increased and then decreased with the ring destruction of the molecular structure during the oxidation process. And the medium molecular weight intermediates of with bicyclic or tricyclic structures posed greater toxicity.

Fig. 7.

The distribution of toxic index of TET transformation products based on the value of m/z (a); and the box chart of the toxic index and ring number of TET transformation products (b).

A predicted toxicity accumulation model (PTAM) was established to evaluate the overall toxicity changes during different oxidation processes. The results of cumulative toxicity were estimated following Eq. (1):

| (1) |

Where Toxt is the cumulative toxicity at the reaction time t (min) during oxidation process; δi is the toxicity partition coefficient of transformation products, which was obtained from ECOSAR program; LC50•i is the value of acute toxicity for daphnid; Ii•t/ITET stands for the relative concentration based on the normalization of peak intensity at the reaction time t, and n is the number of transformation products in each oxidation processes. Due to the difference in the corresponding intensity of the mass spectrum peaks of products, all cumulative toxicity comparisons are limited to the individual analysis of each oxidation process.

Fig. 8a-c displayed the toxicity changes of TET degradation in free, mixed and bound states over time during UV process. The total cumulative toxicity gradually increased with time, and the m/z = 287.1 and 315.1 were the main toxic components, while the total cumulative toxicity was effectively suppressed after the mixing and combining, which might be owing to that the shading effect of HA weakened the degradation of TET. The same phenomenon as UV process, the total cumulative toxicity gradually increased with time in UV/H2O2 (Fig. 8d-f), but the major contributor of toxicity was identified as m/z = 201.1. Due to that, the HA could quench part of hydroxyl radicals, the degradation pathway from m/z = 245.0 to m/z = 201.1 was inhibited, resulting in that the m/z = 245.0 became the most toxic substance after binding interaction. As for the UV/PS process (Fig. 8g-i), the product m/z = 201.1 was the substance with the highest toxicity, and its toxic accumulation rate was gradually increasing in the free, mixed and bound TET degradation, which was attributed to that the binding interaction promoted the generation of product m/z = 201.1. In terms of CNTs/PS process (Fig. 8j–l), the toxicity of m/z = 374.1, 301.1, 273.1 and 255.1 decreased, but the toxicity of m/z = 201.1 increased after mixing and binding between TET and HA, which was consistent with the conclusion on the effect of binding in TET degradation pathway in Fig. S8-S11.

Fig. 8.

The toxic index changes of transformation products of TET in free, mixed and bound states during (a)–(c) UV, (d)–(f) UV/H2O2, (g)–(i) UV/PS and (j)–(l) CNTs/PS processes ([HA] = 3 mg/L, [TET] = 20 μM, [H2O2] = 200 μM, [PS] = 100 μM, [CNTs] = 0.05 g/L, initial pH 6.5).

4. Conclusions

In this study, four oxidation processes were adopted for the degradation of tetracycline (TET) in free, mixed and bound states, and the transformation products distribution and toxicity assessment were focused on. The transformation products of free TET during UV, UV/H2O2, UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes were 7, 7, 14 and 17, respectively. The binding interaction significantly decreased the amounts of transformation products in UV, UV/H2O2 processes, except to UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes, which might be owing to the strong oxidation performance of UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes. HA would affect the degradation pathway of TET by combining with the dimethylamino group to weaken the attack on the originally vulnerable site (-N(CH3)2), and further induce the direct cleavage of the ring A and B of bound TET to generate bicyclic structure transformation products (such as m/z = 245.0 and 201.1) with higher toxicity. The results of the toxicity accumulation model calculation indicated that the binding roles would significantly reduce the overall toxicity during TET degradation in UV and UV/H2O2 processes by weakening the degradation of TET and reducing the amounts of degradation products. However, it would increase the overall toxicity by promoting the generation of higher toxic transformation products in UV/PS and CNTs/PS processes.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 51878422), Science and Technology Projects of Sichuan Province (2018 HH0104), Science and Technology Bureau of Chengdu (2017-GH02-00010-342 HZ) and Innovation Spark Project in Sichuan University (Grant No. 2082604401254) for the financial support.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ese.2021.100127.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Yao H., Pei J., Wang H., Fu J. Effect of Fe(II/III) on tetracycline degradation under UV/VUV irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;308:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martinez J.L. Environmental pollution by antibiotics and by antibiotic resistance determinants. Environ. Pollut. 2009;157:2893–2902. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2009.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J., Zhi D., Zhou H., He X., Zhang D. Evaluating tetracycline degradation pathway and intermediate toxicity during the electrochemical oxidation over a Ti/Ti4O7 anode. Water Res. 2018;137:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tang J., Shi T.Z., Wu X.W., Cao H.Q., Li X.D., Hua R.M., Tang F., Yue Y.D. The occurrence and distribution of antibiotics in Lake Chaohu, China: seasonal variation, potential source and risk assessment. Chemosphere. 2015;122:154–161. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pena A., Paulo M., Silva L.J.G., Seifrtova M., Lino C.M., Solich P. Tetracycline antibiotics in hospital and municipal wastewaters: a pilot study in Portugal. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010;396:2929–2936. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-3581-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volkers G., Palm G.J., Weiss M.S., Wright G.D., Hinrichs W. Structural basis for a new tetracycline resistance mechanism relying on the TetX monooxygenase. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:1061–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang W., Moore I.F., Koteva K.P., Bareich D.C., Hughes D.W., Wright G.D. TetX is a flavin-dependent monooxygenase conferring resistance to tetracycline antibiotics. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:52346–52352. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pi Z., Li X., Wang D., Xu Q., Tao Z., Huang X., Yao F., Wu Y., He L., Yang Q. Persulfate activation by oxidation biochar supported magnetite particles for tetracycline removal: performance and degradation pathway. J. Clean. Prod. 2019;235:1103–1115. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang Y.D., Zheng N., Han R.W., Zheng B.Q., Yu Z.N., Li S.L., Zheng S.S., Wang J.Q. Occurrence of tetracyclines, sulfonamides, sulfamethazine and quinolones in pasteurized milk and UHT milk in China's market. Food Control. 2014;36:238–242. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y., Gao Y., Jiang J., Shen Y.M., Pang S.Y., Wang Z., Duan J.B., Guo Q., Guan C.T., Ma J. Transformation of tetracycline antibiotics during water treatment with unactivated peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;379 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang B., Wang C., Cheng X., Zhang Y., Li W., Wang J., Tian Z., Chu W., Korshin G.V., Guo H. Water Research; 2021. Interactions between the Antibiotic Tetracycline and Humic Acid: Examination of the Binding Sites, and Effects of Complexation on the Oxidation of Tetracycline; p. 202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palm G.J., Lederer T., Orth P., Saenger W., Takahashi M., Hillen W., Hinrichs W. Specific binding of divalent metal ions to tetracycline and to the Tet repressor/tetracycline complex. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2008;13:1097–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00775-008-0395-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang H., Yao H., Sun P., Li D., Huang C.H. Transformation of tetracycline antibiotics and Fe(II) and Fe(III) species induced by their complexation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:145–153. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b03696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y., Li H., Wang Z.P., Tao T., Hu C. Photoproducts of tetracycline and oxytetracycline involving self-sensitized oxidation in aqueous solutions: effects of Ca2+ and Mg2+ J. Environ. Sci. 2011;23:1634–1639. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(10)60625-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wammer K.H., Slattery M.T., Stemig A.M., Ditty J.L. Tetracycline photolysis in natural waters: loss of antibacterial activity. Chemosphere. 2011;85:1505–1510. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2011.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma J., Zhou H., Yan S., Song W. Kinetics studies and mechanistic considerations on the reactions of superoxide radical ions with dissolved organic matter. Water Res. 2018;149:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feng H., Liu M., Zeng W., Chen Y. Optimization of the O3/H2O2 process with response surface methodology for pretreatment of mother liquor of gas field wastewater. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2021;15 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scaria J., Anupama K.V., Nidheesh P.V. Tetracyclines in the environment: an overview on the occurrence, fate, toxicity, detection, removal methods, and sludge management. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;771:145291. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li J., Zhu J., Fang L., Nie Y., Tian N., Tian X., Lu L., Zhou Z., Yang C., Li Y. Enhanced peroxymonosulfate activation by supported microporous carbon for degradation of tetracycline via non-radical mechanism. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2020:240. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han C.H., Park H.D., Kim S.B., Yargeau V., Choi J.W., Lee S.H., Park J.A. Oxidation of tetracycline and oxytetracycline for the photo-Fenton process: their transformation products and toxicity assessment. Water Res. 2020;172:115514. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mboula V.M., Hequet V., Gru Y., Colin R., Andres Y. Assessment of the efficiency of photocatalysis on tetracycline biodegradation. J. Hazard Mater. 2012;209:355–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song D., Cheng H.Y., Liu R.P., Qiang Z.M., He H., Liu H.J., Qu J.H. Enhanced oxidation of tetracycline by permanganate via the alkali-induced alteration of the highest occupied molecular orbital and the electrostatic potential. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2017;56:4703–4708. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang Y., Zhang H., Zhang J.H., Lu C., Huang Q.Q., Wu J., Liu F. Degradation of tetracycline in aqueous media by ozonation in an internal loop-lift reactor. J. Hazard Mater. 2011;192:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2011.04.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang P., He Y.L., Huang C.H. Reactions of tetracycline antibiotics with chlorine dioxide and free chlorine. Water Res. 2011;45:1838–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2010.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mangalgiri K.P., Blaney L. Elucidating the stimulatory and inhibitory effects of dissolved organic matter from poultry litter on photodegradation of antibiotics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017;51:12310–12320. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.7b03482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ye Z.X., Shao K.L., Huang H., Yang X. Tetracycline antibiotics as precursors of dichloroacetamide and other disinfection byproducts during chlorination and chloramination. Chemosphere. 2021:270. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou S.Q., Shao Y.S., Gao N.Y., Zhu S.M., Ma Y., Deng J. Chlorination and chloramination of tetracycline antibiotics: disinfection by-products formation and influential factors. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2014;107:30–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng X., Guo H., Zhang Y., Korshin G.V., Yang B. Insights into the mechanism of nonradical reactions of persulfate activated by carbon nanotubes: activation performance and structure-function relationship. Water Res. 2019;157:406–414. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2019.03.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen C., Wu Z., Zheng S., Wang L., Niu X., Fang J. Comparative study for interactions of sulfate radical and hydroxyl radical with phenol in the presence of nitrite. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:8455–8463. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gao Y., Ji Y., Li G., An T. Mechanism, kinetics and toxicity assessment of OH-initiated transformation of triclosan in aquatic environments. Water Res. 2014;49:360–370. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen J., Xu X., Zeng X., Feng M., Qu R., Wang Z., Nesnas N., Sharma V.K. Ferrate(VI) oxidation of polychlorinated diphenyl sulfides: kinetics, degradation, and oxidized products. Water Res. 2018;143:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2018.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang C.J., Su H.W. Identification of sulfate and hydroxyl radicals in thermally activated persulfate. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2009;48:5558–5562. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang B., Zhou P., Cheng X., Li H., Huo X., Zhang Y. Simultaneous removal of methylene blue and total dissolved copper in zero-valent iron/H2O2 Fenton system: kinetics, mechanism and degradation pathway. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019;555:383–393. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2019.07.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong Z.J., Jiang C.C., Guo Q., Li J.W., Wang X.X., Wang Z., Jiang J. A novel diagnostic method for distinguishing between Fe(IV) and (∗)OH by using atrazine as a probe: clarifying the nature of reactive intermediates formed by nitrilotriacetic acid assisted Fenton-like reaction. J. Hazard Mater. 2021;417:126030. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheng X., Guo H., Li W., Yang B., Wang J., Zhang Y., Du E. Metal-free carbocatalysis for persulfate activation toward nonradical oxidation: enhanced singlet oxygen generation based on active sites and electronic property. Chem. Eng. J. 2020:396. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheng X., Guo H., Zhang Y., Wu X., Liu Y. Non-photochemical production of singlet oxygen via activation of persulfate by carbon nanotubes. Water Res. 2017;113:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2017.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lv J., Zhang S., Wang S., Luo L., Cao D., Christie P. Molecular-scale investigation with ESI-FT-ICR-MS on fractionation of dissolved organic matter induced by adsorption on iron oxyhydroxides. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016;50:2328–2336. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.5b04996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Herzsprung P., Osterloh K., von Tumpling W., Harir M., Hertkorn N., Schmitt-Kopplin P., Meissner R., Bernsdorf S., Friese K. Differences in DOM of rewetted and natural peatlands - results from high-field FT-ICR-MS and bulk optical parameters. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;586:770–781. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He C., Zhang Y., Li Y., Zhuo X., Li Y., Zhang C., Shi Q. In-house standard method for molecular characterization of dissolved organic matter by FT-ICR mass spectrometry. ACS Omega. 2020;5:11730–11736. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.0c01055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.von Gunten U. Oxidation processes in water treatment: are we on track? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018;52:5062–5075. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.8b00586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li M., Liu F., Ma Z., Liu W., Liang J., Tong M. Different mechanisms for E. coli disinfection and BPA degradation by CeO2-AgI under visible light irradiation. Chem. Eng. J. 2019;371:750–758. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li W., Guo H., Wang C., Zhang Y., Cheng X., Wang J., Yang B., Du E. ROS reevaluation for degradation of 4-chloro-3,5-dimethylphenol (PCMX) by UV and UV/persulfate processes in the water: kinetics, mechanism, DFT studies and toxicity evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;390 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao W., Zhou B. Assessing the role of CNTs in H2O2/Fe(III) Fenton-like process: mechanism, DFT calculations and ecotoxicity evaluation. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2021:259. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deng Y., Tang L., Zeng G., Wang J., Zhou Y., Wang J., Tang J., Wang L., Feng C. Facile fabrication of mediator-free Z-scheme photocatalyst of phosphorous-doped ultrathin graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets and bismuth vanadate composites with enhanced tetracycline degradation under visible light. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018;509:219–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y.-Y., Ma Y.-L., Yang J., Wang L.-Q., Lv J.-M., Ren C.-J. Aqueous tetracycline degradation by H2O2 alone: removal and transformation pathway. Chem. Eng. J. 2017;307:15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou Y., Gao Y., Jiang J., Shen Y.-M., Pang S.-Y., Wang Z., Duan J., Guo Q., Guan C., Ma J. Transformation of tetracycline antibiotics during water treatment with unactivated peroxymonosulfate. Chem. Eng. J. 2020;379:122378. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wu Y., Deng L., Bu L., Zhu S., Shi Z., Zhou S. Degradation of diethyl phthalate (DEP) by vacuum ultraviolet process: influencing factors, oxidation products, and toxicity assessment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019;26:5435–5444. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-3914-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pan X., Wei J., Zou M., Chen J., Qu R., Wang Z. Products distribution and contribution of (de)chlorination, hydroxylation and coupling reactions to 2,4-dichlorophenol removal in seven oxidation systems. Water Res. 2021;194:116916. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2021.116916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.