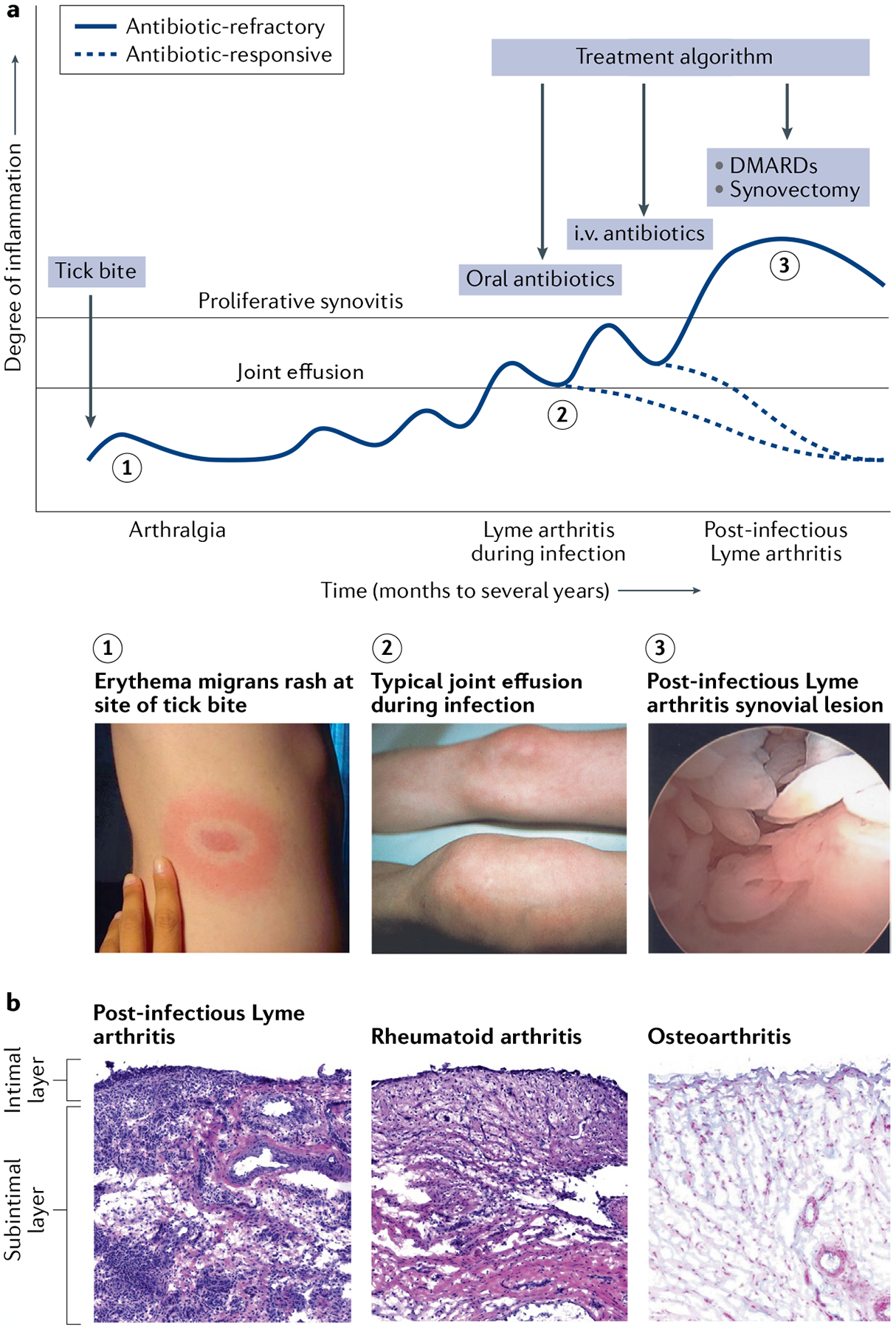

Fig. 2 |. Lyme arthritis stages and characteristics.

a | In untreated patients, Lyme disease occurs in stages, with different manifestations present at each stage. A slowly expanding erythema migrans rash commonly appears 3 to 32 days after a bite by a Borrelia burgdorferi-infected Ixodes tick (1), which can be accompanied by flu-like symptoms such as fever, headache, myalgias, arthralgias, malaise and fatigue. In the north-eastern states of the USA, Lyme arthritis typically causes large joint effusions, particularly affecting the knees (2), which develop a median of 6 months after the initial skin lesion. Arthritis usually resolves after 1–3 months of oral and, if necessary, intravenous (i.v.) antibiotic therapy (antibiotic-responsive Lyme arthritis). In a small subset of patients, arthritis persists or worsens despite 2–3 months of antibiotic therapy and apparent spirochaetal killing (post-infectious Lyme arthritis). These patients typically develop a highly proliferative synovial lesion (3) that does not respond to further courses of antibiotic therapy (antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis). Treatments such as DMARDs or arthroscopic synovectomy help to resolve their arthritis. b | The synovial lesion in post-infectious Lyme arthritis is similar to the lesion in rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory arthritides. By contrast, osteoarthritis synovium typically has minimal cellular infiltrate, the intimal layer is not inflamed or thickened, and the subintimal layer is composed of healthy, intact microvasculature and highly organized collagen fibres. In this figure, the synovial lesions from Lyme arthritis and rheumatoid arthritis are stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and osteoarthritis synovium is stained with H&E and Alcian blue to show acidic glycosaminoglycans on the outer surface of collagen fibre bundles and along the synovial lining. Image of the knee in part a reprinted with permission from REF.137, Elsevier.