Highlights

-

•

Selecting a proper corticosteroid regimen in terms of dosage and duration is crucial

-

•

Survival benefit analysed between high vs. low-moderate dose steroid recipients

-

•

Lesser mortality benefits seen with higher doses of steroids in early-onset hypoxia

-

•

Statistically insignificant when therapy is initiated late in course of the disease

-

•

NLR, a marker of the immune response varied between treatment groups

Keywords: COVID-19, Hypoxia, Early-onset, Late-onset, Corticosteroids, Mortality

Abstract

Background

Corticosteroid dosing in COVID-19 cases associated with early-onset and late-onset hypoxia have not been separately explored.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we divided hypoxic COVID-19 cases into groups based on timing of initiation of corticosteroids relative to onset of symptoms; Group A (≤6th day), Group B (7th-9th day) and Group C (≥10th day), each group being sub-grouped into high and low-to-moderate dose corticosteroid recipients. Cox regression with propensity scoring was used to compare 28-day mortality between high and low-to-moderate dose recipients separately in Group A, Group B, Group C.

Results

Among 505 patients included, propensity score matched Cox regression showed greater risk of all-cause mortality among high dose recipients in Group A [HR= 7.35, 95%CI 3.36-16.11, p-value<0·01, N=114] and Group B [HR=3.17, 95%CI 1.65-6.07, p-value<0·01, N=251]. In Group C, mortality was lowest [12.8% (18/140)] with no significant difference between sub-groups [HR=2.52, 95%CI 0.22-29.15, p-value=0.459, N=140]. Kruskal-Wallis Test between Group A, Group B and Group C for six pre-defined exposure variables showed significant differences for Neutrophil:Lymphocyte Ratio (NLR).

Conclusion

When steroids were initiated early (owing to an earlier onset of hypoxic symptoms), a high dose of corticosteroid was associated with greater overall 28-day mortality compared to a low-to-moderate dose. NLR, a marker for individual immune response, varied between treatment groups.

INTRODUCTION

Corticosteroids are found to have mortality benefits in hypoxic COVID-19 cases. These benefits have recently been established in large trials like the Recovery trial [20] and a large meta-analysis [25] that pooled the result of seven Randomized Clinical Trials (RCTs). There is some consensus between globally accepted guidelines [28,10,31] regarding the dosing and duration of corticosteroid therapy in hypoxic COVID-19 cases, but these guidelines are not clear as to whether the dosing and regimen of corticosteroid therapy should vary between cases presenting with early-onset and late-onset hypoxia. In this study, we tried to separately evaluate the impact of different doses of corticosteroids in three different groups (based on the day of onset of symptoms when steroids were initiated) of hypoxic COVID-19 patients.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

A multicentric, institution-based retrospective cohort study was conducted among hypoxic COVID-19 patients admitted and treated between Feb-Aug 2021 during second wave of COVID-19 pandemic in India. This study was conducted across two tertiary-care super-specialty hospitals in Eastern India, Rampurhat Government Medical College & Hospital and AMRI Hospitals, Mukundapur, Kolkata. The study population included hospital-admitted hypoxic COVID-19 patients who received corticosteroid therapy and other supportive medications.

Study Participants

Hypoxic (SpO2≤94%) COVID-19 RT-PCR positive adult (age>18 years) patients initiated on corticosteroids within 24 hours of hospital admission and continued so for at least three days were included. Cases receiving corticosteroids due to concomitant autoimmune /immunosuppressive disease (Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Post-Renal Transplant, etc.) or those receiving so in the last seven days (as available from past medication records), SpO2≥95% and those receiving tocilizumab, antibody-cocktail, baricitininb or any other immunomodulatory therapy for the present illness, were excluded. We also excluded patients with inadequately evidenced clinical history regarding onset of symptoms and those with co-existing bacterial sepsis (as seen from high pro-calcitonin levels or positive culture reports).

Data Sources

Hospital-based records from either institution were filled into pre-designed data extraction forms and codified into MS Excel. Treatment history was reviewed including medications received, dosage and preparation of corticosteroids used and day of symptom when corticosteroids were started (day 1 being the 1st day of symptom onset). We analyzed the entire study population in three separate groups based on the day of symptoms when corticosteroids were initiated. The patients were divided into three groups. In Group A, patients had received steroids on or before day 6 of onset of symptoms. Group B included patients initiated on corticosteroids between days 7-9. Group C patients received steroids on or after day 10 of symptom onset. [COVID-19 illness is known to exhibit three grades of increasing severity with correspondingly different clinical findings, response to therapy, and clinical outcome. Timelines for grouping the cohort were selected arbitrarily (i.e. ≤6 days, 7-9 days and ≥10 days) keeping in mind the 3 corresponding distinct stages of disease [24] and accordingly different immune responses by the host cells [23]].

Each group was subdivided into two subgroups based on whether they received a high-dose (>40 mg prednisolone or 6 mg dexamethasone equivalent /day) or a low-to-moderate dose (≤40 mg prednisolone or 6 mg dexamethasone equivalent /day) of corticosteroids within 24 hours of hospital admission. This dose cut-off of 40 mg prednisolone was selected based on a few trials [14,15] that considered this dose as a low dose. A major trial by Recovery Group used equivalent dose ranges in their study population [20]. A standard steroid-conversion calculator ascertained equivalent doses of corticosteroids.

Study Variables

The baseline study variables included the following:

-

a)

Demographic parameters [Age [19]; Sex; Body Mass Index (BMI) [17]; Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) [30]; Vaccination Status]

-

b)

Clinical parameters [Quick COVID-19 Severity Index (qCSI, comprising of Respiratory Rate, SpO2, Oxygen Demand) [21]; Pulse Rate; Systolic and Diastolic Blood Pressure (SBP and DBP); SOFA Score; Treatment with Remdesivir]

-

c)

Laboratory parameters [White Blood Count (WBC); Hemoglobin in gm/dl (Hb%); Neutrophil:Lymphocyte ratio (NLR) [3]; serum Alanine Transferase (ALT); serum Creatinine; Serum C-Reactive Protein (CRP) [26]; serum D-dimer levels]

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measure in this study was all-cause mortality over 28 days post-hospital admission. Secondary outcome measures included length of hospital stay, percentage of ICU admissions, and the percentage receiving oxygen through face masks /cannula, through invasive or non-invasive ventilation. We compared primary and secondary outcomes between high-dose and low-to-moderate dose recipient sub-groups in each of Group A, Group B and Group C.

Additionally, from the before-mentioned baseline variables, we selected six variables (Age, BMI, CCI, qCSI, CRP, NLR) that could potentially impact treatment outcomes, based on literature review of similar studies. We intended to look for differences in these variables between the study groups, Group A, Group B and Group C.

Statistical Analysis

To compare the primary outcome, i.e., 28 day mortality between the high-dose and low-to-moderate dose corticosteroid recipients in each of Group A, Group B and Group C, survival analysis was done using the following methods:

-

a

Cox regression adjusting for baseline covariates [Age, Sex, BMI, CCI, qCSI, Pulse Rate, Body Temperature (in degrees Fahrenheit), SBP, DBP, NLR, serum D-Dimer values, CRP, WBC, Hb%, ALT, Creatinine, Remdesivir Status, SOFA score and Vaccination status]

-

b

Cox regression with propensity score adjustment along with adjusted baseline covariates.

-

c

Cox regression with IPTW with adjusted baseline covariates.

-

d

Cox regression in propensity score matched data set with adjusted baseline covariates.

The proportional hazard assumption of the Cox model was tested by the log(-log(survival)) graph versus the length of a hospital stay along with the global Schoenfeld residual. In every group (Group A, Group B, Group C), three different propensity scoring methods (covariate adjustment using propensity score, inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) using propensity score and propensity score matching) were used to minimize selection bias and confounding [2] while estimating the effect of the intervention on outcomes.

Based on a thorough literature review and clinical evidence, the potential confounders identified were Age, BMI, qCSI, CCI, CRP, and NLR. Propensity scoring was done by binary logistic regression for these potential confounders. Matching was done separately within each of Group A, Group B and Group C between high-dose and low-to-moderate dose corticosteroid recipients. For propensity scoring, a separate model was developed for each group. Initially, nearest neighbor score matching (1:1) with 0·2 calipers without replacement yielded poor balance in standardized mean difference (SMD>0·1). Therefore, optimal matching (1:1) was tried using the Optmatch package, which showed SMD<0·1, indicating adequate balance [34]. In addition to Cox proportional hazard regression, the Kaplan-Meier survival plot was used to compare the mortality over time in propensity score-matched cohorts in each group.

To compare the secondary outcome parameters between the high-dose and low-to-moderate dose recipient sub-groups in each of Groups Group A, Group B and Group C, an unpaired t-test was done. The normality of data was calculated using One-Sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov testing. A p-value ≤0·05 with a confidence interval (CI) of 95% was considered statistically significant. All tests were two-sided. Baseline variables among three groups of high-dose and low-to-moderate dose corticosteroid recipients were expressed as mean with standard deviation (SD) and median with interquartile ranges (IQR) for numerical variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables.

Kruskal-Wallis test followed by post-hoc Dunn's test was done to compare the six pre-defined baseline variables between Group A, Group B and Group C. Post-hoc Bonferroni-adjusted significance tests for pairwise comparisons were done for those variables that rejected the null hypothesis in the independent Kruskal-Wallis test.

Missing data were addressed as per Rubin's typology [22]. The null hypothesis for Little's MCAR test was “data missing completely at random”. Missing data were calculated by the multiple imputation method from five imputed data sets. Data were codified and calculated with the help of statistical software SPSS (version 26·0) and R (version R-4.1.2).

RESULTS

A total of 1102 case records of hypoxic COVID-19 patients treated between February to August ’21, were screened for this study. 597 patients were excluded and 505 patients meeting all inclusion criteria were selected [Figure 1]. All were hospital inpatients and received IV corticosteroids as per physician choice, guided mainly by the existing national guideline (AIIMS/ ICMR-COVID-19 National Task Force/ Joint Monitoring Group [[1]GHS], 2022) or Recovery Protocol [20]. Patients having a prolonged hospital course were seen to receive corticosteroids for 7-10 days generally as per ICMR guidelines (AIIMS/ ICMR-COVID-19 National Task Force/ Joint Monitoring Group [[1]GHS], 2022) and for those who recovered within a few days of therapy, corticosteroids were stopped as hypoxia got corrected.

Figure 1.

Study flow Diagram

The entire study population was subdivided into three groups: Group A had 114 (22.57%) patients, Group B had 251 (49.70%) patients, and Group C had 140 (27.72%) patients. We conducted propensity score based 1:1 optimal matching with six pre-defined exposure variables (demographic characteristics, clinical parameters and laboratory values) for the entire study population [Supplementary Appendix; Figure S.1]. The SMD for these variables were calculated between matched and unmatched cohorts besides the p-value. SMD of all the six variables of the matched cohort was <0·1. [Table 1] The proportional hazard assumption tested with Global Schoenfeld residual held valid for Group A and Group B (p>0·05) but not for Group C (p<0·05). [Supplementary Appendix; Table S.1] The log(-log(survival)) graph versus the length of a hospital stay seemed to be parallel in Group A and Group B but not in Group C. [Supplementary Appendix; Figure S.2]

Table 1.

Demographic Table of Group A, Group B and Group C (unmatched and matched dataset)

| Unmatched Data | Matched Data | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sl No | Characteristicsa,c | Low-to-moderate Dose Recipient | High Dose Recipient | p-Value | SMD | Low-to-moderate Dose Recipient | High Dose Recipient | p-Value | SMD | ||

| DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE | |||||||||||

| 1. | Ageb | Group A (mean (SD)) | 57.30 (10.88) | 59.87 (14.85) | 0.299 | 0.197 | 57.30 (10.88) | 58.44 (14.66) | 0.645 | 0.089 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 54.00 [44.50, 63.75] | 55.00 [44.00, 65.00] | 0.615 | 0.057 | 54.00 [44.50, 63.75] | 52.00 [42.25, 65.00] | 0.937 | 0.024 | |||

| Group C (mean (SD)) | 56.86 (12.41) | 54.42 (13.86) | 0.299 | 0.186 | 56.86 (12.41) | 56.02 (14.09) | 0.749 | 0.064 | |||

| 2. | Sex | Group A | Male (%) | 21 (38.9) | 23 (38.3) | 1.000 | 0.011 | 21 (38.9) | 21 (38.9) | 1.000 | <0.001 |

| Female (%) | 33 (61.1) | 37 (61.7) | 33 (61.1) | 33 (61.1) | |||||||

| Group B | Male (%) | 41 (43.6) | 65 (41.4) | 0.792 | 0.045 | 41 (43.6) | 35 (37.2) | 0.458 | 0.130 | ||

| Female (%) | 53 (56.4) | 92 (58.6) | 53 (56.4) | 59 (62.8) | |||||||

| Group C | Male (%) | 22 (43.1) | 33 (37.1) | 0.59 | 0.124 | 22 (43.1) | 19 (37.3) | 0.687 | 0.120 | ||

| Female (%) | 29 (56.9) | 56 (62.9) | 29 (56.9) | 32 (62.7) | |||||||

| 3. | BMIb | Group A (mean (SD)) | 26.00 (3.01) | 26.32 (3.65) | 0.607 | 0.097 | 26.00 (3.01) | 26.19 (3.63) | 0.768 | 0.057 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 25.54 [23.60, 28.10] | 24.80 [22.80, 27.70] | 0.187 | 0.195 | 25.54 [23.60, 28.10] | 25.45 [23.60, 28.56] | 0.820 | 0.022 | |||

| Group C (mean (SD)) | 26.75 (3.56) | 24.85 (3.67) | 0.004 | 0.524 | 26.75 (3.56) | 26.75 (3.06) | 0.994 | 0.001 | |||

| 4. | CHARLSON COMORBIDITY INDEXb | Group A (median [IQR]) | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 0.661 | 0.076 | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 0.770 | 0.055 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 0.153 | 0.191 | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 0.778 | 0.043 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 2.00 [0.00, 3.00] | 0.337 | 0.146 | 2.00 [1.00, 3.00] | 2.00 [0.50, 3.50] | 0.967 | 0.010 | |||

| 5 | Vaccination_status-double dose (%) | Group A | 2 (3.7) | 4 (6.7) | 0.682 | 0.134 | 2 (3.7) | 3 (5.6) | 1.000 | 0.088 | |

| Group B | 8 (8.5) | 10 (6.4) | 0.615 | 0.082 | 8 (8.5) | 4 (4.3) | 0.372 | 0.175 | |||

| Group C | 5 (9.8) | 12 (13.5) | 0.6 | 0.115 | 5 (9.8) | 5 (9.8) | 1.000 | <0.001 | |||

| CLINICAL PARAMETERS | |||||||||||

| 6. | Q COVID INDEXb | Group A (median [IQR]) | 8.00 [7.00, 9.00] | 8.00 [7.00, 9.00] | 0.547 | 0.067 | 8.00 [7.00, 9.00] | 8.00 [7.00, 9.00] | 0.683 | 0.044 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 8.00 [7.00, 10.00] | 9.00 [7.00, 10.00] | 0.878 | 0.009 | 8.00 [7.00, 10.00] | 9.00 [7.00, 10.00] | 0.977 | 0.020 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 9.00 [7.50, 11.00] | 8.00 [7.00, 11.00] | 0.382 | 0.14 | 9.00 [7.50, 11.00] | 8.00 [7.00, 11.00] | 0.783 | 0.029 | |||

| a. SPO2 | Group A (mean (SD)) | 90.00 [89.00, 91.00] | 90.00 [89.00, 91.00] | 0.762 | 0.052 | 90.00 [89.00, 91.00] | 90.00 [89.00, 91.00] | 0.726 | 0.090 | ||

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 89.00 [85.00, 90.00] | 89.00 [86.00, 90.00] | 0.969 | 0.015 | 89.00 [85.00, 90.00] | 89.00 [85.00, 90.00] | 0.634 | 0.110 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 88.00 [85.00, 90.00] | 89.00 [86.00, 90.00] | 0.336 | 0.153 | 88.00 [85.00, 90.00] | 89.00 [85.50, 90.00] | 0.734 | 0.041 | |||

| b. RESP RATE (/Min) | Group A (median [IQR]) | 24.00 [23.00, 29.00] | 25.00 [23.00, 30.00] | 0.477 | 0.116 | 24.00 [23.00, 29.00] | 25.50 [23.00, 29.75] | 0.435 | 0.133 | ||

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 26.00 [22.00, 31.00] | 26.00 [22.00, 31.00] | 0.959 | 0.005 | 26.00 [22.00, 31.00] | 26.00 [23.00, 31.00] | 0.699 | 0.067 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 25.00 [22.00, 28.50] | 26.00 [23.00, 31.00] | 0.408 | 0.159 | 25.00 [22.00, 28.50] | 26.00 [23.00, 31.00] | 0.483 | 0.158 | |||

| c. Oxygen Requirement (Lit/min) | Group A (median [IQR]) | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 0.901 | 0.028 | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 0.992 | <0.001 | ||

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 4.00 [3.00, 6.00] | 5.00 [3.00, 6.00] | 0.266 | 0.156 | 4.00 [3.00, 6.00] | 5.00 [3.00, 6.00] | 0.469 | 0.118 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 0.616 | 0.083 | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 0.928 | 0.017 | |||

| 7. | Pulse Rate (/min) | Group A (mean (SD)) | 94.40 (23.15) | 93.30 (24.51) | 0.806 | 0.046 | 94.40 (23.15) | 94.11 (24.68) | 0.949 | 0.012 | |

| Group B (mean (SD)) | 105.51 (16.44) | 107.53 (21.01) | 0.426 | 0.107 | 105.51 (16.44) | 107.53 (21.39) | 0.468 | 0.106 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 101.00 [98.00, 113.98] | 99.00 [90.00, 105.00] | 0.041 | 0.363 | 101.00 [98.00, 113.98] | 99.00 [90.00, 103.50] | 0.020 | 0.543 | |||

| 8. | Temperature | Group A (median [IQR]) | 98.60 [98.53, 99.50] | 98.60 [98.30, 98.77] | 0.008 | 0.431 | 98.60 [98.53, 99.50] | 98.60 [98.35, 98.79] | 0.012 | 0.425 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 98.65 [98.40, 99.38] | 98.60 [98.40, 99.27] | 0.672 | 0.073 | 98.65 [98.40, 99.38] | 98.60 [98.40, 98.94] | 0.373 | 0.180 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 98.70 [98.50, 98.80] | 98.60 [98.30, 98.70] | 0.01 | 0.304 | 98.70 [98.50, 98.80] | 98.60 [98.34, 98.70] | 0.134 | 0.145 | |||

| 9. | SBP (mmHg) | Group A (median [IQR]) | 131.00 [120.00, 144.75] | 130.00 [120.00, 140.00] | 0.620 | 0.003 | 131.00 [120.00, 144.75] | 130.00 [120.00, 139.25] | 0.417 | 0.058 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 128.00 [120.00, 132.00] | 130.00 [120.00, 140.00] | 0.096 | 0.247 | 128.00 [120.00, 132.00] | 130.00 [120.00, 140.00] | 0.083 | 0.293 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 122.42 [118.00, 133.24] | 120.00 [110.00, 129.00] | 0.009 | 0.479 | 122.42 [118.00, 133.24] | 120.06 [110.00, 130.00] | 0.061 | 0.369 | |||

| 10. | DBP (mmHg) | Group A (median [IQR]) | 80.00 [72.00, 80.00] | 78.50 [70.00, 80.00] | 0.512 | 0.012 | 80.00 [72.00, 80.00] | 78.50 [70.00, 80.00] | 0.445 | 0.060 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 76.00 [70.00, 83.75] | 74.00 [70.00, 80.00] | 0.356 | 0.133 | 76.00 [70.00, 83.75] | 74.00 [70.00, 81.50] | 0.568 | 0.075 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 70.00 [70.00, 80.00] | 70.00 [70.00, 80.00] | 0.539 | 0.066 | 70.00 [70.00, 80.00] | 70.00 [70.00, 71.50] | 0.291 | 0.232 | |||

| LAB PARAMETERS | |||||||||||

| 11. | SOFA Score | Group A (median [IQR]) | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 0.072 | 0.234 | 4.00 [3.00, 5.00] | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 0.143 | 0.179 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 0.444 | 0.048 | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 0.384 | 0.062 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 0.368 | 0.162 | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 3.00 [3.00, 4.00] | 0.368 | 0.162 | |||

| 12. | Haemoglobin (gm/dL) | Group A (mean (SD)) | 11.71 (1.76) | 11.47 (1.81) | 0.467 | 0.137 | 11.71 (1.76) | 11.44 (1.79) | 0.432 | 0.152 | |

| Group B (mean (SD)) | 11.76 (1.97) | 12.00 (2.08) | 0.371 | 0.118 | 11.76 (1.97) | 12.35 (2.11) | 0.051 | 0.286 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 11.50 [11.00, 12.40] | 12.60 [10.40, 13.70] | 0.081 | 0.174 | 11.50 [11.00, 12.40] | 12.60 [10.40, 13.80] | 0.153 | 0.201 | |||

| 13. | ALT (U/L) | Group A (median [IQR]) | 53.21 [41.50, 70.00] | 52.00 [44.75, 68.25] | 0.820 | 0.168 | 53.21 [41.50, 70.00] | 52.00 [45.00, 68.75] | 0.946 | 0.136 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 55.00 [44.25, 69.25] | 54.50 [43.00, 70.00] | 0.583 | 0.227 | 55.00 [44.25, 69.25] | 54.50 [43.00, 70.00] | 0.583 | 0.227 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 53.00 [43.50, 65.00] | 50.00 [40.00, 75.00] | 0.969 | 0.195 | 53.00 [43.50, 65.00] | 49.00 [38.50, 76.50] | 0.601 | 0.236 | |||

| 14. | White Blood Cell Count (× 109/L) | Group A (median [IQR]) | 9.90 [8.51, 12.80] | 13.08 [9.58, 17.56] | 0.004 | 0.567 | 9.90 [8.51, 12.80] | 12.83 [9.46, 17.26] | 0.006 | 0.538 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 11.02 [8.25, 15.76] | 10.11 [7.98, 13.79] | 0.408 | 0.112 | 11.02 [8.25, 15.76] | 10.73 [7.94, 14.55] | 0.768 | 0.045 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 11.86 [8.56, 13.91] | 9.23 [7.83, 13.50] | 0.056 | 0.212 | 11.86 [8.56, 13.91] | 9.36 [8.13, 14.55] | 0.242 | 0.085 | |||

| 15. | Neutrophil: Lymphocyte Ratiob | Group A (median [IQR]) | 12.95 [5.29, 17.24] | 12.60 [6.38, 15.19] | 0.708 | 0.033 | 12.95 [5.29, 17.24] | 12.40 [5.73, 15.24] | 0.649 | 0.024 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 6.75 [5.10, 12.73] | 7.18 [4.70, 12.10] | 0.623 | 0.026 | 6.75 [5.10, 12.73] | 7.40 [4.73, 11.93] | 0.604 | 0.017 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 5.50 [4.96, 8.37] | 5.24 [4.55, 6.78] | 0.216 | 0.233 | 5.50 [4.96, 8.37] | 5.70 [4.57, 7.90] | 0.893 | 0.008 | |||

| 16. | Creatinine (mg/dL) | Group A (median [IQR]) | 1.05 [0.89, 1.23] | 0.91 [0.73, 1.25] | 0.042 | 0.330 | 1.05 [0.89, 1.23] | 0.90 [0.73, 1.23] | 0.037 | 0.332 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 0.90 [0.76, 1.19] | 0.93 [0.79, 1.20] | 0.456 | 0.034 | 0.90 [0.76, 1.19] | 0.95 [0.79, 1.22] | 0.323 | 0.006 | |||

| Group C | 0.82 [0.60, 1.10] | 0.98 [0.86, 1.18] | 0.053 | 0.121 | 0.82 [0.60, 1.10] | 0.88 [0.79, 1.10] | 0.429 | 0.046 | |||

| 17. | C-Reactive Protein (mg/L)b | Group A (median [IQR]) | 55.90 [44.85, 77.50] | 67.00 [50.00, 88.00] | 0.112 | 0.180 | 55.90 [44.85, 77.50] | 60.85 [49.62, 79.50] | 0.373 | 0.022 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 85.45 [69.00, 124.75] | 90.00 [70.00, 126.00] | 0.538 | 0.053 | 85.45 [69.00, 124.75] | 87.50 [67.20, 122.75] | 0.955 | 0.014 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 86.00 [64.00, 127.00] | 98.00 [65.00, 128.00] | 0.64 | 0.018 | 86.00 [64.00, 127.00] | 104.60 [60.50, 135.50] | 0.508 | 0.065 | |||

| 18. | D-DIMER (ng/mL FEU)d | Group A (median [IQR]) | 565.00 [470.98, 695.00] | 550.94 [442.50, 662.50] | 0.566 | 0.072 | 565.00 [470.98, 695.00] | 550.94 [427.50, 665.00] | 0.651 | 0.043 | |

| Group B (median [IQR]) | 915.00 [682.50, 2667.50] | 780.00 [610.00, 1420.00] | 0.007 | 0.399 | 915.00 [682.50, 2667.50] | 770.00 [610.00, 1377.50] | 0.007 | 0.394 | |||

| Group C (median [IQR]) | 1390.00 [925.00, 1825.00] | 950.00 [860.00, 1570.00] | 0.014 | 0.504 | 1390.00 [925.00, 1825.00] | 960.00 [850.00, 1610.00] | 0.058 | 0.470 | |||

| ANTIVIRAL THERAPY | |||||||||||

| 19. | REMEDESIVIR THERAPY (%) | Group A | 35 (64.8) | 32 (53.3) | 0.255 | 0.235 | 35 (64.8) | 31 (57.4) | 0.554 | 0.152 | |

| Group B | 42 (44.7) | 84 (53.5) | 0.194 | 0.177 | 42 (44.7) | 47 (50.0) | 0.559 | 0.107 | |||

| Group C | 24 (47.1) | 26 (29.2) | 0.044 | 0.374 | 24 (47.1) | 18 (35.3) | 0.314 | 0.241 | |||

BMI body mass index, ALT alanine aminotransferase, SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, SMD standardized mean difference

For normal distribution of continuous variables, means±standard deviation and for non-normal distribution medians (interquartile ranges, IQRs) were presented. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages within parentheses were presented

Only predefined six variables were considered in propensity score optimal (1:1) matching. The standardized mean difference of clinical characteristics was less than 10% to indicate the balance between high-dose corticosteroid and low to moderate dose corticosteroid groups.

Missing data on demographic profile, vital signs, and laboratory tests were imputed from 5 imputed data sets for the entire cohort analysis and the propensity score matching analysis. Descriptive results from five imputed data sets were shown

All the D dimer values of various units are converted into ng/mL.

Group A showed overall mortality of 64% (n=73, N=114) [Table 2]. Cox regression analysis adjusted with all the baseline covariates showed a higher risk of post-admission death in patients receiving high-dose corticosteroids in this group [Adjusted Hazard Ratio (HR) 5·036, 95% CI 2·461-10·302, p<0·001]. Propensity score adjusted Cox regression, IPTW regression and Cox regression with propensity score optimal matching (1:1) adjusted with the same covariates showed similar results [Figure 2].

Table 2.

28-Day Mortality and Relative Number of Remedesivir Recipients in Various Groups and Sub-Groups

| Groups | High dose Corticosteroid Recipient | Low-Moderate dose Corticosteroid Recipient | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Mortality | Number receiving Remedesivir | Overall Mortality | Number receiving Remedesivir | Overall Mortality | Number receiving Remedesivir | |

| Group A | 45/60 (75%) | 32/60 (53%) | 28/54 (51%) | 35/54 (64%) | 73/114 (64%) | 67/114 (58%) |

| Group B | 63/157 (40%) | 84/157 (53%) | 33/94 (35%)a | 42/94 (44%) | 96/251 (38.2%) | 126/251 (49%) |

| Group C | 9/89 (10%) | 26/89 (29%) | 9/51 (17%)a | 24/51 (47%) | 18/140 (12.8%) | 50/140 (35%) |

The overall mortality in low-moderate dose corticosteroids of Group B and Group C (those who received corticosteroids> 6 days of onset of symptoms) was 28% (n= 42/145)

Figure 2.

Forest plot comparing hazard ratios (HR) in Group A, Group B and Group C, CI=confidence interval

In each group (Gr A, Gr B, Gr C) Survival analysis was carried out between high dose vs low-moderate dose corticosteroid therapy recipients was analysed using the following methods-

*Cox regression with adjusted baseline covariates (Age, Sex, BMI, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), Quick Covid-19 Severity Index, Pulse, Body temperature-degrees Fahrenheit, SBP, DBP Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio, D-Dimer, CRP, WBC count, Hb, ALT, Creatinine, and Remdesivir)

[#SOFA SCORE & VACCINATION STATUS along with other existing covariables adjusted Cox regression showed on S.Table-9]

**Cox regression with propensity score adjustment along with adjusted baseline covariates

*** Cox regression with IPTW (Inverse probability treatment weighting) with adjusted baseline covariates

****Cox regression with adjusted baseline covariates in propensity score-matched data set

Time to the event is mortality (seen up to 28 days), HR in each group is assessed here between high dose relative to low-moderate dose.

Group B had a mortality of 38·2% (n=96, N=251) [Table 2]. We repeated the same statistical methods for survival analysis as above and found a higher risk of mortality at day 28 among high-dose recipients than low-to-moderate dose recipients in this group. [Adjusted HR: 3·375, CI 1·91-5·94, p<0·001] [Figure 2].

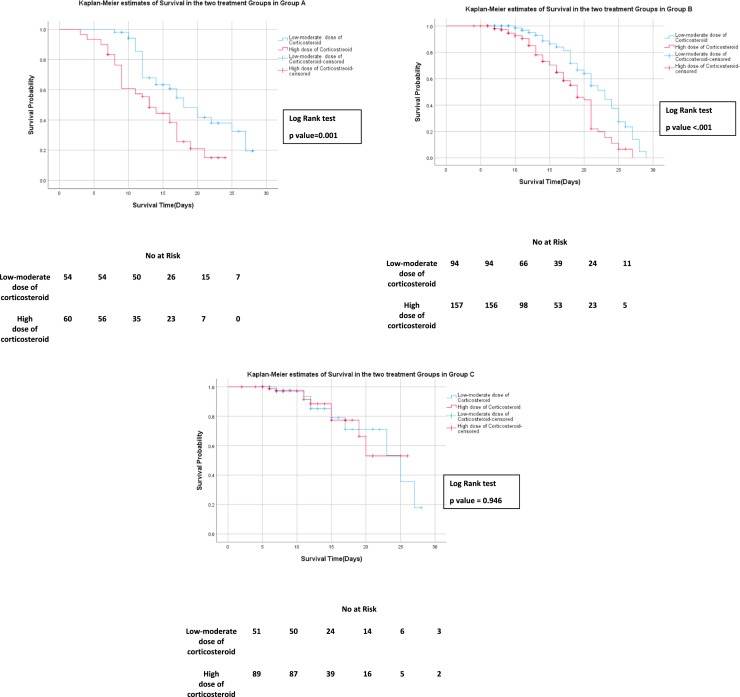

The mortality rate in Group C was the lowest at 12.8% (n=18, N=140) [Table 2] using the same analytical methods as before. There was no statistically significant (p>0·05) mortality difference between high-dose and low-to-moderate dose recipients in this group. [Figure 2 & Figure 4]

Figure 4.

Kaplan-Meier Survival estimates in High Dose corticosteroid vs Low to moderate dose recipients in Unmatched Groups(Gr-A, Gr-B, Gr-C)

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for 28 days since hospital admission: Cumulative Survival among the unmatched cohorts between High Dose corticosteroid and Low to moderate dose recipients in three separate groups.

(Group A) received steroids on or before day 6 of symptom onset

(Group B) received steroids between 7- 9 days of symptom onset

(Group C) received steroids on or after day 10 of symptom onset.

The numbers below the figures denote the number of patients ‘at risk’ in each group.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves between high-dose versus low-to-moderate dose corticosteroids in unmatched data in each of Group A, Group B and Group C are depicted in Figure 4.

The results of the comparison in secondary outcome parameters between high-dose and low-to-moderate dose recipient sub-groups in each of Group A, Group B and Group C have been depicted in Table 3.

Table 3.

Secondary outcome parameters in Group A, Group B and Group C

| Secondary outcome parameters | High-dose Corticosteroid Recipient | Low-moderate dose Corticosteroid Recipient | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | |||

| Length of stay (median [IQR]) | 13.00 [8.00, 17.00] | 14.00 [11.00, 20.00] | 0.01 |

| ICU admission (%) | 57 (95.0) | 45 (83.3) | 0.0i65 |

| Invasive Ventilation (%) | 31 (51.7) | 18 (33.3) | 0.059 |

| Non-Invasive ventilation (BIPAP/HFNO) (%) | 30 (50.0) | 33 (61.1) | 0.262 |

| Face mask/O2 cannula (%) | 2 (3.3) | 3 (5.6) | 0.666 |

| Group B | |||

| Length of stay (median [IQR]) | 12.00 [8.00, 17.00] | 13.00 [9.00, 19.75] | 0.06 |

| ICU admission (%) | 125 (79.6) | 69 (73.4) | 0.278 |

| Invasive Ventilation (%) | 54 (34.4) | 12 (12.8) | <0.001 |

| Non-Invasive ventilation (BIPAP/HFNO) (%) | 69 (43.9) | 56 (59.6) | 0.019 |

| Face mask/O2 cannula (%) | 34 (21.7) | 25 (26.6) | 0.442 |

| Group C | |||

| Length of stay (median [IQR]) | 8.00 [6.00, 12.00] | 9.00 [7.00, 15.00] | 0.193 |

| ICU admission (%) | 41 (46.1) | 25 (49.0) | 0.86 |

| Invasive Ventilation (%) | 5 (5.6) | 5 (9.8) | 0.497 |

| Non-Invasive ventilation (BIPAP/HFNO) (%) | 10 (11.2) | 6 (11.8) | 1 |

| Face mask/O2 cannula (%) | 50 (56.2) | 26 (51.0) | 0.599 |

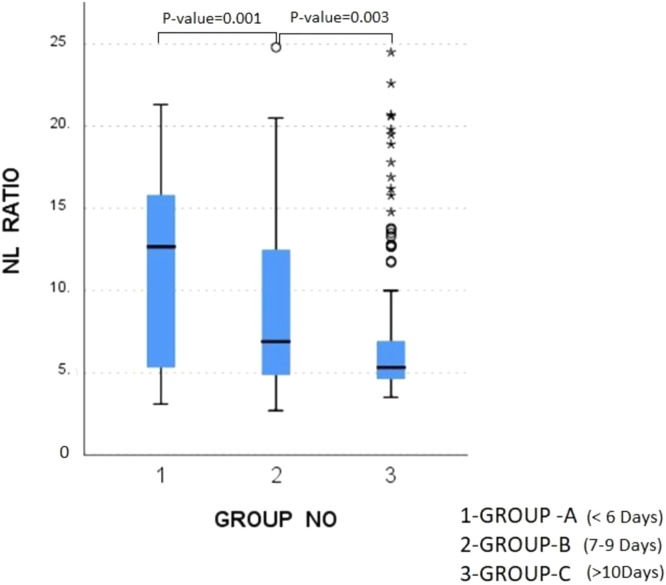

Kruskal-Wallis Test was done in-between Group A, Group B and Group C for the six exposure variables (age, BMI, CCI, qCSI, NLR, CRP). Two of the variables (BMI and CCI) showed no significant differences (p>0·05) [Supplementary Appendix; Table S.2]. In contrast, the rest of the four variables (age, qCSI, NLR, CRP) showed significant differences (p<0·05) between high-dose and low-to-moderate dose subgroups, in at least one of the groups, Group A, Group B or Group C. Statistically significant difference was seen between Group A & Group B (Bonferroni adjusted p=0·001) and between Group B & Group C (Bonferroni adjusted p=0·003) only for the NLR [Figure 3], among these four variables [Supplementary Appendix; Table S.3]. Missing values for each of the variables in either Group A, Group B or Group C did not exceed 10% and have been detailed in the Supplementary Appendix [Table S.6]. As such, most received dexamethasone some received methylprednisolone. Types and relative percentages of corticosteroids received are shown in the Supplementary Appendix [Table S.8].

Figure 3.

Box plot, Comparison of N/L ratio between three groups based on the day since onset of symptoms of Covid-19 when corticosteroids were initiated

The horizontal line in each box plot shows the median, and the bottom and top of the box are located at the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers represent values that are more than 1.5 times the interquartile range from the border of each box. Data points indicate outliers outside this range.

DISCUSSION

This multicentric retrospective study was carried out across two tertiary care referral hospitals in India, where most of the population was of Asian-Indian ethnicity. Data were collected from hospital records of cases affected during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, where the Delta strain B.1.617.2 [18] was predominant and the major portion of the population was not fully vaccinated. A surveillance study on COVID-19 strain done on a cohort in the same population showed absolute B.1.617.2 predominance.

While the overall mortality was found to be high in Group A and Group B, the lowest was in Group C. High-dose corticosteroid therapy in Group A and Group B was seen to be associated with greater mortality when compared to low-to-moderate dose therapy. The overall mortality in low-to-moderate dose corticosteroid sub-groups in Group B and Group C (those who received corticosteroids after 6 days of onset of symptoms) was seen to be 42/145 (28%). [Table 2] This finding is similar to that of the mortality seen in the Recovery trial (23% and 29%) in hypoxic cases. On the contrary, no statistically significant difference in 28-day mortality was observed in Group C between the two corticosteroid receiving subgroups similar to the Covid-Steroid 2 Trial. We found the overall mortality to be less in Group C (12·8%) where Ana Fernandez Cruz et al. [6] showed similar findings in in-hospital mortality (13·9%) among corticosteroids treated patients, where patients received corticosteroid therapy for a median of 10 days after the onset of symptoms, and in-hospital mortality was not different between the two corticosteroid recipients groups.

When comparing the secondary outcomes among treatment subgroups in Group A, Group B and Group C, high-dose recipients in Group A showed a significantly greater need for invasive and non-invasive ventilation oxygen requirements as compared to the low-to-moderate dose subgroup. No such difference was seen in Group C. These findings partially corroborate our study findings related to the primary outcome.

While steroids are proven to be beneficial in COVID-19, eventually multiple recommending bodies including the British Medical Journal [28], WHO [31] and IDSA [10] advocated for use of a low-dose steroid in hospitalized hypoxic patients. We searched for available evidence with high-dose corticosteroids. Few recently published RCTs that have used different dosing of corticosteroids have concluded differing opinions. Manuel Taboad et al. [27] in their RCT showed high-dose dexamethasone to reduce clinical worsening in hypoxic COVID-19 patients. Another three-arm RCT by Toroghi N et al. [29] showed higher doses of dexamethasone increased the adverse events and worsened survival in hospitalized patients compared to low-dose dexamethasone. Again, Maskin, Luis Patricio et al. [14] in a multicenter, open-label RCT showed, 28 days after randomization, there was no difference in ventilation-free days between high and low-dose dexamethasone groups. The large comparative COVID STEROID 2 [15] trial showed that 12 mg/day of dexamethasone compared with 6 mg/day did not result in statistically significantly more days alive without life support at 28 days.

Though there are limitations in the above-mentioned RCTs, e.g., not fulfilling power, receiving steroids before the intervention, and using other immunomodulators (IL-6 antagonist) in their course, these studies have thrown some light on the effects of different dose ranges of steroid therapy among hypoxic patients. The findings in the above-mentioned RCTs varied one from the other. It is now known that in COVID-19 infection, the nature of the immune response in persons developing early-onset hypoxia and late-onset hypoxia is not the same, a variation in responses to corticosteroids is therefore scientifically plausible. One of the possibilities for the conflicting opinions could be arising from bias due to differences in the day of onset of symptoms when corticosteroids were initiated.

Amongst quite many studies conducted to explore the appropriate dose and duration of corticosteroids in COVID-19, very few considered the day of symptom onset when deciding the dosage of corticosteroids on initiation. Bahl et al. [5] concluded corticosteroids are initiated more than 7 days after onset of symptoms and may be considered during 48-72 hours post-admission, and should be initiated if patients remain hospitalized at 72 hours. The host immune response, which varies from person to person, and day to day, is known to play a significant role in COVID-19 infection pathophysiology. Immune status is often clinically reflected by the onset and severity of symptoms [23] and a variation in the hematologic profile. A marker for such is the NLR [33,23]. As consistent across many studies, an abnormal innate-immune response characterized by an unduly excessive cytokine/chemokine signature predominates the immuno-pathogenesis in moderate-to-severe COVID-19 infection. A high neutrophil percentage (the most important cell marker for natural immunity) is seen in blood [11] and lungs. Severe COVID-19 presents with hyper-inflammation, immune paralysis and massive vascular inflammation, frequently triggering ARDS [32]. In contrast, the end-stage disease is generally not associated with preferential T-cell abundance in the lung tissues [12]. In COVID-19 infection, an initial innate immune response is followed by an adaptive immune response [23]. In the initial phases of the disease, viral load increases in the upper respiratory tract with viral evasion of the lungs. If the adaptive immune response starts late, the outcome may be fatal because without substantive adaptive immunity, the viral burden may become high [23]. Corticosteroids are immunomodulators, causing lymphopenia, reducing CD4+/CD8+ T-cells, and NK cells, and promoting neutrophilia [13]. With the degree of lymphocyte-suppression being dose-dependent [7], it is feasible that in high-dose corticosteroid recipients in the early course of the disease, an attempt to stop viral replication by the body's adaptive immunity may be attenuated by corticosteroid therapy itself. This may boost viral replication leading to greater chances of cytokine storm, disease worsening, longer duration of hospital stay, enhancing chances of hospital-acquired infections [8] and secondary sepsis.

In a similar line to these assumptions, the results of a meta-analysis on the use of corticosteroids in influenza state that corticosteroids might alter the immune reactions leading to prolonged viremia and delayed viral clearance, ultimately increasing the risk of mortality [16]. In studies on MERS [4] and earlier SARS infections, corticosteroids were seen to prolong viral replication [9], and their beneficial role was questioned. The Recovery group found no mortality benefit during the early days of corticosteroid therapy in non-hypoxic COVID-19 patients [20]. This could be attributed, at least in part, to prolonged viral replication.

Among the six pre-defined baseline covariates in the three study groups, the NLR was the only marker significantly different across all groups and the mean NLR value was found to be highest in Group A and lowest in Group C. Similarly, overall mortality was also seen to be highest in Group A and lowest in Group C. A prospective cohort study [33] showed NLR to be greater in patients with deterioration than in those without deterioration and higher in patients with serious clinical outcomes (shock, death) than in patients without so.

Patients in Group A and Group B (having an overall higher NLR), receiving low-to-moderate dose corticosteroids showed lower mortality. Lymphopenia by corticosteroid being dose-dependent [7], lymphocyte suppression may have been optimal, creating a balance between cytokine suppression and viral replication. In Group C, the mortality difference between the high-dose and low-to-moderate corticosteroid recipients was not statistically significant. Since these patients presented on or after day 10, probably viral replication was no longer an essential driving factor and adaptive immunity (lower NLR, higher lymphocyte percentage) may have taken over.

In this study, the groups showing greater mortality (Group A & Group B) showed a higher NLR, such findings are exciting and raise a question, as to whether tailoring corticosteroid therapy based on individual immune response may yield better outcomes, and whether the prior assessment of immune response using markers like NLR or others could serve in determining the appropriate dosage of corticosteroid therapy.

Our study is unique in the sense that we have conducted it in a predominantly unvaccinated population, and that we have considered not only various dose ranges of corticosteroid but also the timing of initiation of corticosteroid therapy relative to the day of symptom onset. We have included patients receiving the first dose of corticosteroid within 24 hours of hospital admission and those on other immunomodulators have been excluded.

Our study had certain limitations, to our perception. Steroid-related ADRs were not well-documented in a subset of patients while they were documented in others. A causality assessment was also not available for some of the documented ADRs. As such, we could not include ADR assessment in our study design. The study population received mainly two types of corticosteroids, methylprednisolone and dexamethasone. We duly converted both types of corticosteroids into an equivalent dose of prednisolone, but the glucocorticoid or mineralocorticoid activity of these two steroids are not the same and this could have affected the outcome. Due to a small observed effect size in Group C, a greater sample size could have increased the power of the study in this group. As per the study protocol and the terms of permission from the institutional ethics committee, we followed up on all the cases up to day 28 of symptoms. For those surviving on day 28, the outcomes beyond day 28 (including mortality, ICU transfer, use of high flow oxygen, non-invasive mechanical ventilation or invasive mechanical ventilation) were not taken into consideration. Radiological assessments are done at admission routinely at the study sites but were inadequately documented for some of the patients. Hence, we could not include radiological data in this study.

To summarize, we studied the effect of high-dose vs low-to-moderate dose steroids at 28 days since hospital admission in hypoxic COVID-19 patients, stratified by the time between the onset of symptoms and initiation of treatment by steroids. We found that a high dose of corticosteroid initiated early since the onset of the disease is associated with lesser mortality benefits as compared to low-to-moderate dose therapy. We also found that this distinction in mortality benefit between high dose low-to-moderate dose of corticosteroids is not statistically significant when the therapy is initiated late in the course of the disease. NLR, a marker of the immune response, was seen to vary between treatment groups. Our study findings incite the need for prospective research to explore factors needing to be considered when selecting the dosage of corticosteroids in COVID-19, for optimal patient benefit.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

This study is a non-sponsored investigator-initiated academic study. The author(s) received no financial support for this research, authorship, and /or publication of this article. All the researchers declare that they do not have any conflict of interest related to the conduct or publication of this research work.

Funding Source

The author(s) received no financial support for this research work or for the authorship and /or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval Statement

Permission to conduct the study was duly obtained from the Institutional Clinical Research Ethics Committees of both institutes. Following ethics committee approval, data were accessed from all subsequent medical records fulfilling the study criteria.

Contributors

AKS led the study conceptualisation and the development of the research question, supported by AM, DG, RC, MM, SBI, DNG, SS and SKT. A literature search was done by AKS, AM, DG, SBI, and SK. AKS, SD, BS, and SBA were responsible for data collection. AKS, SD and DB accessed and verified the data, developed the statistical analysis plan and performed the analyses. AKS, SD, BS, and RR wrote the first draft of the paper. Review and editing were done by SKT, SS, MM, SD, and DNG. All authors contributed to the interpretation and discussion of the results, critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content, and approved the final and revised versions and manuscript submission. The corresponding author had the final responsibility regarding the decision to submit the article for publication.

Data Sharing

Individual participants’ data (de-identified), as available from case records, will remain archived for five years after the publication of the research but are not freely available. Upon reasonable request directed to the corresponding author at arpitsaha21@gmail.com, anonymized data will be shared with researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge the active cooperation and support from the administrative heads, managerial heads and staff at Rampurhat Govt Medical College and Hospital and Amri Hospitals Mukundapur, Kolkata.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijregi.2022.09.007.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.AIIMS/ICMR-COVID-19 National Task Force/ Joint Monitoring Group (Dte.GHS) 2022. CLINICAL GUIDANCE FOR MANAGEMENT OF ADULT COVID-19 PATIENTS.https://www.icmr.gov.in/pdf/covid/techdoc/COVID_Clinical_Management_14012022.pdf accessed May 1, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali MS, Prieto-Alhambra D, Lopes LC, Ramos D, Bispo N, Ichihara MY, et al. Propensity score methods in health technology assessment: Principles, extended applications, and recent advances. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alkhatip AAAMM, Kamel MG, Hamza MK, Farag EM, Yassin HM, Elayashy M, et al. The diagnostic and prognostic role of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2021;21 doi: 10.1080/14737159.2021.1915773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arabi YM, Mandourah Y, Al-Hameed F, Sindi AA, Almekhlafi GA, Hussein MA, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for critically ill patients with middle east respiratory syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197 doi: 10.1164/rccm.201706-1172OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bahl A, Johnson S, Chen NW. Timing of corticosteroids impacts mortality in hospitalized COVID-19 patients. Intern Emerg Med. 2021;16:1593–1603. doi: 10.1007/s11739-021-02655-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernández-Cruz A, Ruiz-Antorán B, Muñoz-Gómez A, Sancho-López A, Mills-Sánchez P, Centeno-Soto GA, et al. A retrospective controlled cohort study of the impact of glucocorticoid treatment in SARS-CoV-2 infection mortality. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e01168. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01168-20. -20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleishaker DL, Mukherjee A, Whaley FS, Daniel S, Zeiher BG. Safety and pharmacodynamic dose response of short-term prednisone in healthy adult subjects: A dose ranging, randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17 doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grasselli G, Scaravilli V, Mangioni D, Scudeller L, Alagna L, Bartoletti M, et al. Hospital-Acquired Infections in Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19. Chest. 2021;160 doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hui DS. Systemic corticosteroid therapy may delay viral clearance in patients with middle east respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197:700–701. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201712-2371ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IDSA Overview of IDSA of Covid -19 treatment guideline. Ver. 2022;90 https://www.idsociety.org/practice-guideline/covid-19-guideline-treatment-and-management/ accessed May 1, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuri-Cervantes L, Pampena MB, Meng W, Rosenfeld AM, Ittner CAG, Weisman AR, et al. Comprehensive mapping of immune perturbations associated with severe COVID-19. Sci Immunol. 2020;5 doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abd7114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao M, Liu Y, Yuan J, Wen Y, Xu G, Zhao J, et al. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26 doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marté JL, Toney NJ, Cordes L, Schlom J, Donahue RN, Gulley JL. Early changes in immune cell subsets with corticosteroids in patients with solid tumors: Implications for COVID-19 management. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8 doi: 10.1136/jitc-2020-001019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maskin LP, Bonelli I, Olarte GL, Palizas F, Velo AE, Lurbet MF, et al. High- Versus Low-Dose Dexamethasone for the Treatment of COVID-19-Related Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: A Multicenter, Randomized Open-Label Clinical Trial. J Intensive Care Med. 2022;37:491–499. doi: 10.1177/08850666211066799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munch MW, Myatra SN, Vijayaraghavan BKT, Saseedharan S, Benfield T, Wahlin RR, et al. Effect of 12 mg vs 6 mg of Dexamethasone on the Number of Days Alive without Life Support in Adults with COVID-19 and Severe Hypoxemia: The COVID STEROID 2 Randomized Trial. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2021;326 doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.18295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ni YN, Chen G, Sun J, Liang BM, Liang ZA. The effect of corticosteroids on mortality of patients with influenza pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2019;23 doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2395-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palaiodimos L, Kokkinidis DG, Li W, Karamanis D, Ognibene J, Arora S, et al. Severe obesity is associated with higher in-hospital mortality in a cohort of patients with COVID-19 in the Bronx, New York. Metabolism. 2020;108 doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.pango-designation. 2021-03-01 n.d. https://cov-lineages.org/lineage.html?lineage=B.1.617.2.

- 19.Petrilli CM, Jones SA, Yang J, Rajagopalan H, O'Donnell L, Chernyak Y, et al. Factors associated with hospital admission and critical illness among 5279 people with coronavirus disease 2019 in New York City: Prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in Hospitalized Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/nejmoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez-Nava G, Yanez-Bello MA, Trelles-Garcia DP, Chung CW, Friedman HJ, Hines DW. Performance of the quick COVID-19 severity index and the Brescia-COVID respiratory severity scale in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a community hospital setting. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102 doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63 doi: 10.1093/biomet/63.3.581. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sette A, Crotty S. Adaptive immunity to SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Cell. 2021;184:861–880. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Siddiqi HK, Mehra MR. COVID-19 illness in native and immunosuppressed states: A clinical–therapeutic staging proposal. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2020;39:405–407. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, Angus DC, et al. Association between Administration of Systemic Corticosteroids and Mortality among Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stringer D, Braude P, Myint PK, Evans L, Collins JT, Verduri A, et al. The role of C-reactive protein as a prognostic marker in COVID-19. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyab012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Taboada M, Rodríguez N, Varela PM, Rodríguez MT, Abelleira R, González A, et al. Effect of high versus low dose of dexamethasone on clinical worsening in patients hospitalised with moderate or severe COVID-19 Pneumonia: an open-label, randomised clinical trial. Eur Respir J. 2021 doi: 10.1183/13993003.02518-2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.thebmj. A living WHO guideline on drugs for covid-19 2020. https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3379 (accessed May 1, 2022).

- 29.Toroghi N, Abbasian L, Nourian A, Davoudi-Monfared E, Khalili H, Hasannezhad M, et al. Comparing efficacy and safety of different doses of dexamethasone in the treatment of COVID-19: a three-arm randomized clinical trial. Pharmacol Reports. 2022;74 doi: 10.1007/s43440-021-00341-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuty Kuswardhani RA, Henrina J, Pranata R, Anthonius Lim M, Lawrensia S, Suastika K. Charlson comorbidity index and a composite of poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2020;14 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.10.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.WHO. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Dexamethasone 2021. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/coronavirus-disease-covid-19-dexamethasone (accessed May 1, 2022).

- 32.Wiersinga WJ, Rhodes A, Cheng AC, Peacock SJ, Prescott HC. Pathophysiology, Transmission, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Review. JAMA - J Am Med Assoc. 2020;324 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.12839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng ZY, Feng SD, Chen GP, Wu JN. Predictive value of the neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio for disease deterioration and serious adverse outcomes in patients with COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21 doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05796-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Z, Kim HJ, Lonjon G, Zhu Y. Balance diagnostics after propensity score matching. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7:16. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.12.10. –16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.