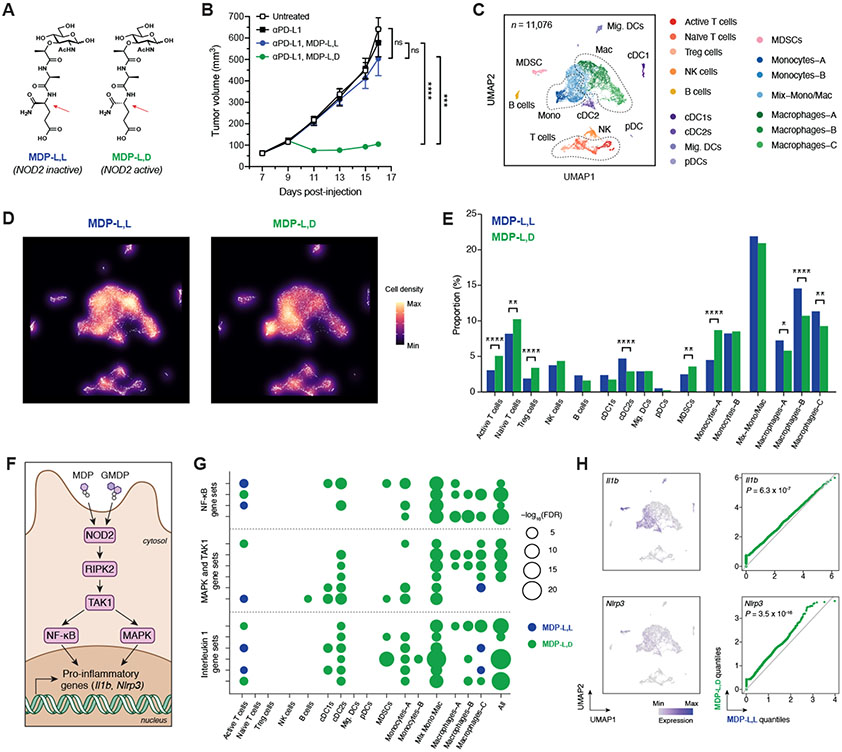

Fig. 4. Peptidoglycan fragment MDP enhances checkpoint blockade efficacy and generates a pro-inflammatory tumor microenvironment.

(A) Chemical structures of the active (l,d) and inactive (l,l) diastereomers of muramyl dipeptide (MDP). Arrows indicate the single altered stereocenter. (B) B16-F10 tumor growth in antibiotic-treated, non-supplemented mice treated with anti–PD-L1 and either MDP-l,d or MDP-l,l starting on day 9. n = 7-8 mice per group. (C) Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plots of scRNA-seq data from CD45+ tumor-infiltrating cells after treatment with anti–PD-L1 and MDP diastereomers. n = 11,076 total cells pooled from six animals per condition. (D) Density plot and (E) quantification of immune cell clusters. (F) Schematic of NOD2-dependent signaling of pro-inflammatory genes. GMDP = GlcNAc-muramyl dipeptide. (G) Bubble plot for enrichment of curated canonical pathway gene sets involving NF-κB, MAPK/TAK1, and interleukin 1 across cell clusters. (H) UMAP plots and paired quantile-quantile plots of NF-κB target genes Il1b and Nlrp3. For (B), data represent mean ± s.e.m. and were analyzed by mixed-effects model with Tukey’s multiple comparisons post-hoc test. For (E), data represent absolute cell counts and were analyzed by Pearson’s chi-squared test for count data with Holm’s correction for multiple comparisons. For (G), false discovery rates (FDR) were obtained by model-based analysis of single transcriptomics (MAST). For (H), data were analyzed with two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001, ns = not significant.