Abstract

As a key component of overall health and quality of life, oral health is recognized by public health organizations globally as a basic human right. Dentists are oral health experts involved in the primary prevention of oral injury and the detection and management of oral diseases. As regulated healthcare professionals, dentists identify and treat dental caries, gum disease, oral cancers, and edentulism, among other conditions. Oral diseases that go undetected and/or untreated burden patients with increased severity of disease and worse health outcomes. The Canadian Dental Association (CDA) recommends routinely scheduled reexamination and preventive care as an essential component of maintaining optimal oral health. Investments by the federal government into dental services for high-risk groups have failed to resolve pervasive oral health disparities among Canadians related to dental care affordability, accessibility, and availability. Vulnerable groups across Canada, including children, seniors in long-term care, Indigenous peoples, new immigrants with refugee status, people with special needs, and the low-income population, have been identified as having challenges accessing regular dental care. Herein, an equity-focused commentary on the current climate of oral healthcare in Canada is presented. We outline how addressing disparities in Canadian dental care will require the engagement of physicians on multiple levels of care, negotiation with both dentists and policymakers, as well as sustained oral health data collection to inform provincial and national decision-making/strategies.

Keywords: Dentistry, Oral health, Health policy, Public health, Health equity, Universal healthcare

Résumé

Élément clé de la santé globale et de la qualité de vie, la santé buccodentaire est reconnue par les organismes de santé publique du monde entier comme un droit humain fondamental. Les dentistes sont des spécialistes de la santé buccodentaire qui s’occupent de la prévention primaire des lésions buccodentaires et de la détection et de la prise en charge des maladies buccodentaires. Ce sont des professionnels de santé réglementés qui détectent et qui traitent les caries dentaires, les maladies des gencives, les cancers buccaux et l’édentement, entre autres affections. Les maladies buccodentaires non détectées ou non traitées s’aggravent et conduisent à de plus mauvais résultats cliniques pour les patients. L’Association dentaire canadienne (ADC) recommande des examens dentaires périodiques et des soins préventifs, car elle les juge essentiels au maintien d’une santé buccodentaire optimale. Les investissements du gouvernement fédéral dans les soins dentaires des groupes fortement exposés n’ont pas permis de résoudre les disparités d’état de santé buccodentaire omniprésentes liées à l’abordabilité, à l’accessibilité et à la disponibilité des soins dentaires. On sait que les groupes vulnérables au Canada, dont les enfants, les aînés résidant dans des établissements de soins de longue durée, les peuples autochtones, les nouveaux immigrants ayant le statut de réfugiés, les personnes ayant des besoins particuliers et la population à faible revenu, ont des problèmes d’accès aux soins dentaires réguliers. Nous commentons ici dans une optique d’équité le climat actuel des soins de santé buccodentaires au Canada. Nous expliquons que pour aborder les disparités dans les soins dentaires canadiens, il faudra mobiliser les médecins de multiples niveaux de soins, négocier à la fois avec les dentistes et les responsables des politiques et assurer une collecte soutenue de données sur la santé buccodentaire pour éclairer les décisions et stratégies provinciales et nationales.

Mots-clés: Dentisterie, santé buccodentaire, politique de santé, santé publique, équité en santé, soins de santé universels

“If access to healthcare is considered a human right, who is considered human enough to have that right?” — Paul Farmer

A publicly funded healthcare system which excludes dentistry care

Dentistry in Canada dates back to the early 1800s, when “dentists” were often craftsmen without knowledge of medicine or surgery but who could pull out aching teeth using creative implements (Morana, 2017). In 1868, the Ontario Dental Association and An Act Respecting Dentistry enacted laws to self-regulate and license dentistry via the Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario (Crawford, 2002b; Morana, 2017). By 1902, other provinces and territories had followed suit, culminating in the establishment of the CDA (Crawford, 2002a, 2002b).

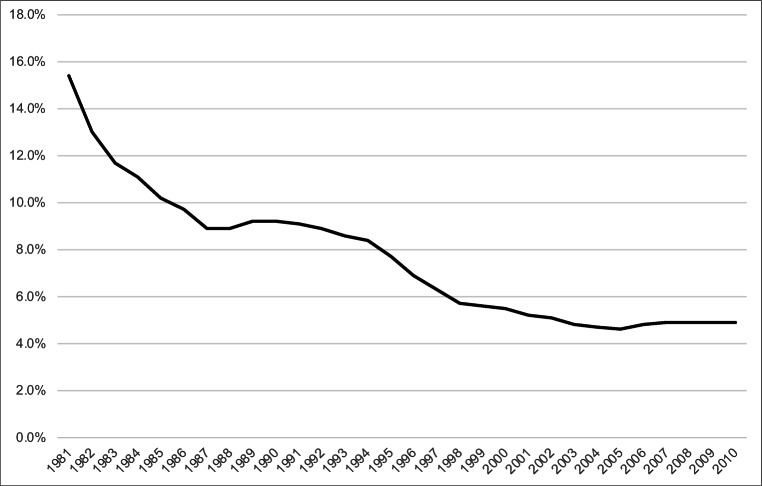

Despite its historic origins, dentistry was excluded from Canadian Medicare due to intersecting professional, socio-cultural, economic, legislative, and epidemiological factors (Quiñonez, 2013). Many dentists, while not entirely opposed to some public system involvement, preferred to exclude dentistry coverage from Medicare to prevent governmental interference in the patient-practitioner relationship (Quiñonez, 2013). The potential economic impacts of financing universal dental care became apparent to Canada by 1948, when the United Kingdom established its National Health Service, and a considerable rise in the demand for dentistry following the implementation of universal coverage was foreseen in Canada (Quiñonez, 2013). Prior to Canada’s Medical Care Act of 1966, the Royal Commission on Health Services in 1964 endorsed the introduction of provincial programs for personal health services targeting dentistry coverage for 3 vulnerable groups: children, expectant mothers, and recipients of public assistance (Hall, 1964; Quiñonez, 2013). Even then, Canada’s public share of total spending on dental services decreased from a high of 15.4% in 1981 to just 4.9% by 2010 (Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), 2011) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Public share of total spending on dental services in Canada, 1981–2010 (Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA), 2011)

Medicare’s exclusion of dentistry led to the emergence of Canada’s first prepaid dental care plans with employer contributions in the late 1960s (Quiñonez, 2013). Today, apart from a few government-funded dental programs for vulnerable groups which vary by province and have narrow eligibility criteria, Canadians mostly receive primary oral healthcare from private dentists. This has resulted in marked health gaps for marginalized groups with the highest levels of oral health problems.

The relationship between income inequality and oral health outcomes

An analysis of studies in the Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) 2007–2009 confirms that income status is strongly associated with dental visits and oral health outcomes. Compared to their higher income counterparts, individuals of lower socioeconomic status experience decreased accessibility to dental care (Fang et al., 2021; Moeller & Quiñonez, 2016; Ravaghi et al., 2020) and poorer oral health outcomes, including greater numbers of decayed or missing teeth, periodontal disease, and oral pain (Fang et al., 2021). Income-related inequalities in self-reported oral health exist across all ages and genders, with 20- to 64-year-olds experiencing the greatest magnitude of inequality (Fang et al., 2021). Moreover, retirees reduce their dental visits as they transition to income reduction and loss of employment-based insurance (Fang et al., 2021). The significance is that oral health inequity due to income disparity covers the entire lifespan. While other indicators such as oral health behaviour, service utilization, and psychosocial influences are possible contributing factors to inequalities in oral health status, there is a paucity of data on these factors. Low income is cited as the only consistent key determinant in the inverse relationship between oral health issues and dental care access, termed the “paradox of need” (Jaffe et al., 2021). Health policies and increasing economic and social inequality continue to affect the accessibility and distribution of resources within and among Canadian municipalities (Moeller & Quiñonez, 2016). The maldistribution of dentists further widens the accessibility gap, as a greater proportion of dentists have practices in areas with a higher average household income (Moeller & Quiñonez, 2016).

The burden of inaccessible dental care on the healthcare system

The lack of adequate and affordable access to dentistry results in the inefficient use of both primary and tertiary care (Brondani & Ahmad, 2017; Singhal et al., 2018). Since only certain surgical-dental services delivered in hospitals are covered under provincial/territorial healthcare plans, low-income individuals predominantly access physician offices or emergency departments (EDs) for standard dental care, or because untreated oral diseases have progressed into worsening medical conditions, including airway compromise, endocarditis, and neck abscess/infection. In fact, ED visits for dental problems in Alberta from 2011 to 2016 were more common than visits for asthma and diabetes (Figueiredo et al., 2017), and in British Columbia, 70% of such visits were identified as non-urgent (Brondani & Ahmad, 2017). In Ontario, nearly 61,000 ED visits for oral health problems were made in 2014, accounting for an estimated cost of at least $31 million (Maund, 2014). With a mean cost of $7,367 per hospital admission due to basic dental problems in Ontario (Quiñonez et al., 2011), an outpatient/preventive approach to oral health could conceivably help minimize burdensome costs for avoidable ED visits. Within Canada, the highest income-related inequities in the probability of visiting a dentist exist in the Atlantic provinces and Quebec (Giannoni & Grignon, 2022). However, beyond socioeconomic barriers to dental care, other factors, including an absence of perceived need for care, decreased oral health literacy, dental fear, and disability, also beget under-utilization of dental services (Mostajer Haqiqi et al., 2016). In Quebec, despite the availability of government-funded dental care for children < 10 years of age, the use of ED visits for dental conditions — particularly dental caries — has increased from 2004 to 2013 (Dos Santos & Dabbagh, 2020). This is partly attributable to oral health knowledge gaps, including the adoption of a “wait-and-see” attitude and/or lay diagnoses made by parents because of poor understandings of oral health (Mostajer Haqiqi et al., 2016). Overall, the alarming frequency of ED visits for oral health concerns, especially in children, immigrants, refugees, homeless individuals, and Indigenous populations, exposes barriers in dental care accessibility for marginalized groups, particularly with respect to urgent care needs (Singhal et al., 2018).

Delayed dental treatment and repeated antimicrobial usage can also potentially worsen a patient’s initial condition (Singhal et al., 2018). The threat of antibiotic resistance has in fact spurred suggestion of antimicrobial stewardship programs for physicians who prescribe medications for dental problems (Okunseri et al., 2012; Singhal et al., 2018). Since primary care physicians are not adequately trained nor possess the proper tools to manage most oral diseases, the etiology of a given clinical presentation is often left untreated (Brondani & Ahmad, 2017). Undiagnosed patients may also receive an opioid prescription for dental pain despite the current context of a Canadian opioid crisis (Pasricha et al., 2018). Without referral to a dentist for expert assessment and treatment, patients will continue to access primary and tertiary care physicians and/or experience worse health outcomes, further burdening the healthcare system. Undetected and/or delayed detection of oral cancer is a prime example. More than half of Alberta’s accumulated oral cancer cases from 2005 to 2017 were diagnosed in stage IV, with the lowest survival rates in Indigenous and rural populations (Badri et al., 2021). Conversely, access to regular dental care has been shown to be a protective factor potentially preventing some oral cavity cancers (Groome et al., 2011).

The magnitude of oral health inequity in Canada versus comparable high-income countries

In Canada and the United States, the absence of a national mandate for public dental care has exacerbated oral health inequity over the past 40 years (Farmer et al., 2016). The prevalence of early childhood caries in 3- to 5-year-old Indigenous children is comparable in both countries, at 85% and 75% for Canada and the USA, respectively (Holve et al., 2021). As of the 2000s, both countries also have comparable rates of individuals who are publicly insured, privately insured, and uninsured for dental care (Farmer et al., 2016). However, despite similarities in dental care financing, the magnitude of health-related inequality in untreated decay and filled teeth is worse in the USA compared to Canada (Chari et al., 2021). One explanation is that Canadians may be more inclined to access physicians for dental-related conditions, including through publicly funded emergency departments, unlike their American counterparts without universal healthcare coverage. Inequalities in the use of dental services within Canada have in fact decreased in most provinces from 2001 to 2016, albeit a definitive underlying explanation has not been determined due to the unclear and complex relationships between factors affecting the affordability of and demand for oral healthcare (e.g., changes in labour and insurance markets, cultural and societal values) (Ravaghi et al., 2020).

While differences exist in the organization of their respective healthcare systems, private dental insurance plays a key role in oral healthcare services in Canada, Australia, and the USA (Neumann & Quiñonez, 2014). In Australia, a hybrid healthcare system exists in which individuals can buy into private insurance coverage plans to gain access to private hospitals while maintaining public hospital access (Dixit & Sambasivan, 2018). Like in Canada, access to private dental services in Australia is possible via both insurance plans and out-of-pocket spending, whereas public dental care access has strict eligibility criteria (Australian Dental Association, 2019). However, government-initiated incentives in Australia encourage the purchasing of private insurance, as individuals or families who do not purchase private insurance must pay a mandatory levy (Dixit & Sambasivan, 2018). In comparison, public coverage for oral healthcare is available to all legal residents of France and the UK. In France, 70% of the fixed fee for regulated items of treatment is reimbursed by public health insurance, but this increases to 100% for individuals aged 6 to 24 (for preventive examination and basic treatment every 3 years), patients with a chronic condition, and pregnant women (for a specific time interval) (Sinclair et al., 2019). Similarly, the UK provides universal oral health coverage for children and adolescents, as do Germany and Sweden (Sinclair et al., 2019). However, compared with France, the UK, and the USA, the proportion of individuals who visited a dentist within the previous 12 months was the highest in Canada (Neumann & Quiñonez, 2014). However, Canada still maintains the highest proportion of individuals with unmet oral healthcare needs, which may be explained by the disparity between Canadians who have the privilege of a high income and/or private dental insurance and thus do not hesitate to frequently access dental care, versus Canadians who cannot afford to visit the dentist routinely (or at all) (Neumann & Quiñonez, 2014).

Ensuring oral health equity for all patients

Primary and tertiary care physicians should assess whether oral health concerns might be the underlying and overriding reason for medical visits from low-income individuals without dental insurance. To improve health equity, these individuals should simultaneously be engaged and empowered by healthcare professionals to act as agents of their own dental care/healthcare. This can be accomplished using a patient-centred approach, in which all clinical decisions rely upon patients’ individual preferences, needs, and values (Lee et al., 2018). A person-centred approach, which considers a person’s living environment, resources, and self-management capacity, may also prove useful in ensuring that dental care transcends the disease-oriented model (Lee et al., 2018). While medical referrals to a dental specialist for consultation and treatment ought to be made if warranted, pervasive inaccessibility and unaffordability will inevitably lead to under-utilization. Advocating for Medicare coverage of dental services rendered post-physician referral will help to mitigate many of the oral health inequities currently being perpetuated by dentistry’s paradoxical exclusion from public insurance coverage in Canada. Such reform could begin by prioritizing funding for several common conditions with the highest conceivable impact, such as abscesses, toothaches, and/or pre-malignant oral lesions. This process is not unlike how an ophthalmologist’s referral to an optician, or a family physician’s referral to a physiotherapist for extended healthcare services would qualify a patient for Medicare coverage outside the list of standard services.

Implications for policy and practice

Barriers to ensuring adequate dental health coverage for vulnerable populations remain. Despite learning about social determinants of health and interprofessional practice, primary and tertiary care physicians may not have the experience, time, or equipment to thoroughly assess the presenting problem as an oral health issue. Notwithstanding the virtues of patient-centred care, patients themselves may not be aware that the source of their medical complaint is an oral disease, further muddying the already-complex process of diagnosis. Additionally, physicians may be reluctant to make medical referrals to dentists and/or reticent to advocate for the inclusion of yet another healthcare professional’s service in Medicare billings. Expanding coverage would require the creation of a health policy which recognizes dentists as highly trained medical specialists in oral health who warrant Medicare insurance coverage. While this solution aligns with the Canada Health Act’s primary objective, attempting to make any changes to legislation and ultimately funding is bound to be a complex and lengthy process. An interim step could be the addition of publicly funded hospital-based dentists who have increased familiarity with dental disease and its management and respond to both emergency and inpatient referrals. Their immediate treatment of oral-specific diseases would be valuable in conceivably preventing further medical decompensation for high-risk populations, decreasing length of stay, as well as reducing emergency room wait times for other patients. At a cost of over $513 per dental ED visit in Ontario, hospital-based dental emergencies are more expensive versus preventive, routine dental visits (Maund, 2014). Failure to promptly treat progressive dental conditions necessitates more comprehensive and costly care in the ED, including significant expenses for the management of advanced sequelae such as dehydration, severe pain, and fever (Friedman et al., 2018). Indeed, a statistically significant difference was found between the average cost of treatment within, versus outside, the ED for children presenting with oral complaints at Canada’s largest pediatric hospital (Friedman et al., 2018).

Dentists’ own opinions on the virtues of publicly financed dental care must also be considered. While most Canadian dentists remain in support of the government having a role in dental care, 57.3% have disagreements/problems with public plans and 33.8% have reported making a business decision to reduce the amount of public insurance in their practice (Quiñonez et al., 2009), likely related to current compensation plans for emergency dental care. A solution may lie in incentivization practices as 68.7% of the nation’s dentists believe the Canadian government should consider tax incentives for dentists who treat socially marginalized groups: people with physical and mental disabilities, homeless individuals, those on social assistance, or those in long-term care (Quiñonez et al., 2009).

Finally, sustained collection of oral health data on the Canadian population serves an important role in informing policymakers on a national oral healthcare strategy. Prior to the Oral Health Module of the CHMS 2007–2009, the only clinically measured national data on oral health conditions was collected 38 years earlier (Health Canada, 2010). Hospital records for admissions related to dental disease are often inaccurate due to competing codes and lack of familiarity with dental disease in the hospital setting. Improvements in capture through the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) could be used as an adjunct to capture hospital-related visits associated with dental disease as a primary or secondary diagnosis. However, the scarce CIHI administrative data for oral healthcare is still a very limited proxy for assessing the burden of oral disease in Canada. The next time the CHMS will collect oral health data is during its seventh cycle, which was originally slated for 2021–2023 but will now be delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Statistics Canada, 2020, 2021). Thus, while dental health disparities have continued to widen, well over a decade will have elapsed until an updated snapshot of oral health in Canada becomes available to policymakers.

Conclusion

Physician advocacy for Medicare-eligible dental referrals may help to reduce oral health inequities for Canada’s vulnerable populations. The extent and success of this solution will depend on the consistent practice of physicians to leverage dentists as oral health specialists via a pathway which can accommodate universal access to the treatment of oral disease. A recent announcement by the federal government of a new dental care program for low-income Canadians gives hope for progress, but only a few vulnerable groups have been explicitly prioritized with limited details offered regarding rollout (Government of Canada, 2022). As stewards of their patients’ overall health, physicians can use their influence to assure holistic healthcare and health equity for all. A critical mass of key stakeholders, including dentists, physicians, as well as dental and medical associations, can mitigate the challenges of making amendments to the Canada Health Act and help to generate health policy which gives due consideration to the maintenance of Canadians’ oral health.

“For me, an area of moral clarity is: you’re in front of someone who’s suffering and you have the tools at your disposal to alleviate that suffering or even eradicate it, and you act” — Paul Farmer

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

All authors conceptualized the work and drafted the initial manuscript. All authors reviewed and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, approved the final manuscript as submitted, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

A previous version of this article indicated that the Canadian Dental Association (CDA) advises most Canadians to visit the dentist every 6 months. The authors would like to correct this error and clarify that according to the Canadian Dental Association (CDA) website, ‘The Canadian Dental Association recommends routinely scheduled reexamination and preventive care as an essential component of maintaining optimal oral health.’ The original article has been updated..

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

11/2/2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.17269/s41997-022-00710-z

References

- Australian Dental Association. (2019). The Australian Dental Health Plan: Achieving optimal oral health. Retrieved on March 12, 2022 from New South Wales, Australia: https://www.ada.org.au/Dental-Professionals/Australian-Dental-Health-Plan/Download-your-copy-of-the-Dental-Health-Plan/Australian-Dental-Health-Plan-2019.aspx

- Badri P, Ganatra S, Baracos V, Lai H, Amin M. Oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancer surveillance and control in Alberta: A scoping review. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2021;84(I4):1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brondani M, Ahmad SH. The 1% of emergency room visits for non-traumatic dental conditions in British Columbia: Misconceptions about the numbers. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2017;108(3):e279–e281. doi: 10.17269/CJPH.108.5915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. (CCPA). (2011). Putting our money where our mouth is: The future of dental care in Canada. Retrieved on January 22, 2022 from Ottawa, ON: https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/2011/04/Putting%20our%20money%20where%20our%20mouth%20is.pdf

- Chari, M., Ravaghi, V., Sabbah, W., Gomaa, N., Singhal, S., & Quinonez, C. (2021). Comparing the magnitude of oral health inequality over time in Canada and the United States. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 1–8. 10.1111/jphd.12486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Crawford, R. (2002a). A century of service (part three of a series). In: A century of service. Retrieved from https://www.cda-adc.ca/_files/about/about_cda/history/HSPart3.pdf

- Crawford, R. (2002b). A century of service (part two of a series). In: A century of service. Retrieved from https://www.cda-adc.ca/_files/about/about_cda/history/HSPart2.pdf

- Dixit SK, Sambasivan M. A review of the Australian healthcare system: A policy perspective. SAGE Open Medicine. 2018;6:1–14. doi: 10.1177/2050312118769211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dos Santos, B. F., & Dabbagh, B. (2020). A 10-year retrospective study of paediatric emergency department visits for dental conditions in Montreal, Canada. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry, 30(6), 741–748. 10.1111/ipd.12651 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fang C, Aldossri M, Farmer J, Gomaa N, Quinonez C, Ravaghi V. Changes in income-related inequalities in oral health status in Ontario, Canada. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2021;49(2):110–118. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer J, McLeod L, Siddiqi A, Ravaghi V, Quinonez C. Towards an understanding of the structural determinants of oral health inequalities: A comparative analysis between Canada and the United States. SSM Popul Health. 2016;2:226–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2016.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figueiredo R, Fournier K, Levin L. Emergency department visits for dental problems not associated with trauma in Alberta, Canada. International Journal of Dentistry. 2017;67(6):378–383. doi: 10.1111/idj.12315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman ME, Quiñonez C, Barrett EJ, Boutis K, Casas MJ. The cost of treating caries-related complaints at a children’s hospital emergency department. Journal of the Canadian Dental Association. 2018;84:i5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannoni, M., & Grignon, M. (2022). Food insecurity, home ownership and income-related equity in dental care use and access: The case of Canada. BMC Public Health, 22(497). 10.1186/s12889-022-12760-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. (2022). Delivering for Canadians now. Retrieved on March 25, 2022 from https://pm.gc.ca/en/news/news-releases/2022/03/22/delivering-canadians-now

- Groome PA, Rohland SL, Hall SF, Irish J, Mackillop WJ, O’Sullivan B. A population-based study of factors associated with early versus late stage oral cavity cancer diagnoses. Oral Oncology. 2011;47(7):642–647. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, E. M. (1964). Royal Commission on Health Services : Volume I. Ottawa, ON: Queen’s Printer. Retrieved on January 22, 2022 from https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2016/bcp-pco/Z1-1961-3-1-1-eng.pdf

- Health Canada. (2010). Report on the findings of the oral health component of the Canadian Health Measures Survey 2007-2009. Retrieved on January 22, 2022 from Ottawa, ON: https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2010/sc-hc/H34-221-2010-eng.pdf

- Holve, S., Braun, P., Irvine, J. D., Nadeau, K., Schroth, R. J., Bell, S. L., ... Fraser-Roberts, L. (2021). Early childhood caries in Indigenous communities. Pediatrics, 147(6), e2021051481. 10.1542/peds.2021-051481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jaffe K, Choi J, Hayashi K, Milloy MJ, Richardson L. A paradox of need: Gaps in access to dental care among people who use drugs in Canada’s publicly funded healthcare system. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2021;29(6):1799–1806. doi: 10.1111/hsc.13289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, H., Chalmers, N. I., Brow, A., Boynes, S., Monopoli, M., Doherty, M., ... Engineer, L. (2018). Person-centered care model in dentistry. BMC Oral Health, 18, 198. 10.1186/s12903-018-0661-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Maund, J. (2014). Information on hospital emergency room visits for dental problems in Ontario. Retrieved on March 12, 2022 from https://www.allianceon.org/Information-Hospital-Emergency-Room-Visits-Dental-Problems-Ontario

- Moeller J, Quiñonez C. The association between income inequality and oral health in Canada: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Health Services. 2016;46(4):790–809. doi: 10.1177/0020731416635078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morana, C. (2017). Quacks and tramps: A brief history of dentistry in Canada. Retrieved on January 22, 2022 from https://150.oda.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/YOHFW2016.pdf

- Mostajer Haqiqi A, Bedos C, Macdonald ME. The emergency department as a ‘last resort’: Why parents seek care for their child’s nontraumatic dental problems in the emergency room. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology. 2016;44(5):493–503. doi: 10.1111/cdoe.12239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, D. G., & Quiñonez, C. (2014). A comparative analysis of oral health care systems in the United States, United Kingdom, France, Canada, and Brazil. Network for Canadian Oral Health Research Working Papers Series, 1(2), 1–18. Retrieved on February 2, 2022 from http://www.ncohr-rcrsb.ca/knowledge-sharing/working-paper-series/content/garbinneumann.pdf

- Okunseri C, Okunseri E, Thorpe JM, Xiang Q, Szabo A. Medications prescribed in emergency departments for nontraumatic dental condition visits in the United States. Medical Care. 2012;50(6):508–512. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318245a575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasricha SV, Tadrous M, Khuu W, Juurlink DN, Mamdani MM, Paterson M, Gomes T. Clinical indications associated with opioid initiation for pain management in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort study. Pain. 2018;159(8):1562–1568. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiñonez, C. (2013). Why was dental care excluded from Canadian Medicare? Network for Canadian Oral Health Research Working Papers Series, 1(1), 1–5. Retrieved on January 22, 2022 from http://www.ncohr-rcrsb.ca/knowledge-sharing/working-paper-series/content/quinonez.pdf

- Quiñonez C, Figueiredo R, Locker D. Canadian dentists’ opinions on publicly financed dental care. Journal of Public Health Dentistry. 2009;69(2):64–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2008.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quiñonez C, Ieraci L, Guttmann A. Potentially preventable hospital use for dental conditions: implications for expanding dental coverage for low income populations. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2011;22(3):1048–1058. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravaghi, V., Farmer, J., & Quinonez, C. (2020). Persistent but narrowing oral health care inequalities in Canada from 2001 through 2016. Journal of the American Dental Association, 151(5), 349–357. 10.1016/j.adaj.2020.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sinclair E, Eaton KA, Widström E. The healthcare systems and provision of oral healthcare in European Union member states. Part 10: comparison of systems and with the United Kingdom. British Dental Journal. 2019;227(4):305–310. doi: 10.1038/s41415-019-0661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singhal S, Quiñonez C, Manson H. Visits for nontraumatic dental conditions in Ontario’s health care system. JDR Clinical & Translational Research. 2018;4(1):86–95. doi: 10.1177/2380084418801273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. (2020). Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS) – Content information sheet 2007-2023. Retrieved on January 22, 2022 from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/survey/household/5071/informationsheet

- Statistics Canada. (2021). Canadian Health Measures Survey (CHMS). Retrieved on January 22, 2022 from https://www.statcan.gc.ca/en/survey/household/5071

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.