To the Editor: On October 29, 2021, the Food and Drug Administration authorized the BNT162b2 vaccine (Pfizer–BioNTech) for emergency use in children 5 to 11 years of age, on the basis of an immunobridging study and a small efficacy study.1 Recent case–control studies have shown modest short-term effectiveness of the BNT162b2 vaccine in this age group during the early phase of the period when the B.1.1.529 (omicron) variant of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was spreading (from mid-December 2021 to mid-February 2022).2-4 We conducted a large cohort study over a 6-month period when the omicron variant was dominant. Here, we report on the protection conferred by the BNT162b2 vaccine and by previous SARS-CoV-2 infection against infection and coronavirus disease 2019 (Covid-19)–related hospitalization and death in children 5 to 11 years of age.

The data sources and statistical methods for this study have been described previously,5 and new details are provided in the Supplementary Methods section in the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org. Among 887,193 children 5 to 11 years of age in the study, 193,346 SARS-CoV-2 infections occurred between March 11, 2020, and June 3, 2022; a total of 309 of the infected children were known to be hospitalized, and 7 were known to have died (Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). A total of 273,157 children had received at least one dose of the BNT162b2 vaccine between November 1, 2021, and June 3, 2022. We used a counting-process extension of the Cox model to formulate the time-varying effects of the BNT162b2 vaccine and previous SARS-CoV-2 infection on the rate of SARS-CoV-2 infection, with adjustment for demographic variables.

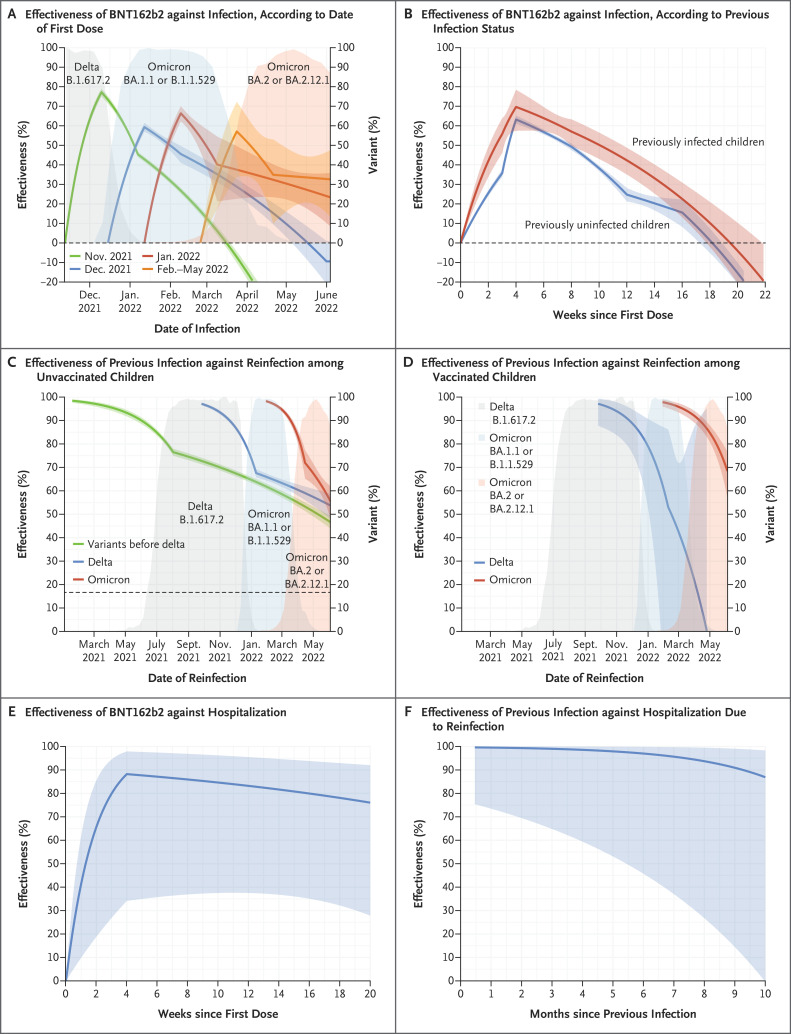

Figure 1 shows the estimated effectiveness of the BNT162b2 vaccine or previous infection, calculated as the percentage reduction in the infection rate. Two doses of BNT162b2 vaccine were effective against SARS-CoV-2 infection, although the effect of the vaccine waned over time. At a similar number of days after the first dose, effectiveness was higher among children vaccinated in November 2021 than among those vaccinated in later months (Figure 1A and Table S2), findings that indicate that vaccination was less effective against the omicron variant than against the B.1.617.2 (delta) variant. The effectiveness of the vaccine alone was higher among previously infected children than among previously uninfected children. Among previously uninfected children, vaccine effectiveness reached 63.2% (95% confidence interval [CI], 61.0 to 65.2) at 4 weeks after the first dose and decreased to 15.5% (95% CI, 8.1 to 22.8) at 16 weeks; among previously infected children, vaccine effectiveness reached 69.6% (95% CI, 57.4 to 78.3) at 4 weeks after the first dose and decreased to 22.4% (95% CI, 13.0 to 30.8) at 16 weeks (Figure 1B and Table S3).

Figure 1. Protection Conferred by Two Doses of BNT162b2 Vaccine and by Previous Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) Infection against Infection and Coronavirus Disease 2019–Related Hospitalization in Children 5 to 11 Years of Age.

The estimated effectiveness of the BNT162b2 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection is shown as a function of time since the first dose, according to the date of the first dose (Panel A; each curve starts at the median date of the first dose) and according to previous infection status (Panel B). The estimated effectiveness of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection against reinfection is shown as a function of time since previous infection, according to the variant type, among unvaccinated children (Panel C) and among vaccinated children (Panel D). In Panels C and D, for each type of previous infection, the curve starts at the median date of the initial diagnosis plus 2 weeks. For variants before delta, the range of these dates is March 11, 2020, to June 30, 2021; for delta, July 1 to December 15, 2021; and for omicron, December 16, 2021, to June 3, 2022. Panel E shows the estimated vaccine effectiveness against hospitalization, and Panel F shows the estimated effectiveness of previous infection against hospitalization due to reinfection. In Panels B, C, and D, effectiveness is calculated for one exposure alone (vaccination or previous infection), given the status of the other exposure. The shaded bands indicate 95% confidence intervals.

The immunity acquired from SARS-CoV-2 infection was high, although it waned over time. Among unvaccinated children, the estimated effectiveness of omicron infection against reinfection with omicron was 90.7% (95% CI, 89.2 to 92.0) at 2 months and 62.9% (95% CI, 58.8 to 66.6) at 4 months (Figure 1C and Table S4). Among vaccinated children, the estimated effectiveness of omicron infection alone against reinfection with omicron was 94.3% (95% CI, 91.6 to 96.1) at 2 months and 79.4% (95% CI, 73.8 to 83.8) at 4 months (Figure 1D).

A total of 15 hospitalizations and no known deaths were noted among the 273,157 vaccinated children (Table S1). Estimates of the effectiveness of two doses of BNT162b2 and of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection against Covid-19–related hospitalization were higher than estimates of the effectiveness against infection, but uncertainties were greater owing to a smaller number of events (Figure 1E and 1F and Tables S5 and S6).

Both the BNT162b2 vaccine and previous infection were found to confer considerable immunity against omicron infection and protection against hospitalization and death. The rapid decline in protection against omicron infection that was conferred by vaccination and previous infection provides support for booster vaccination.

Our study is limited by unmeasured confounding and underreporting of Covid-19 cases. Specifically, waning effects of both vaccination and previous infection may have been confounded by earlier infection and earlier vaccination in high-risk children. In addition, differential ascertainment of Covid-19 cases between vaccinated and unvaccinated children would bias the estimation of vaccine effectiveness.

Supplementary Appendix

Disclosure Forms

This letter was published on September 7, 2022, at NEJM.org.

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this letter at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Food and Drug Administration. FDA authorizes Pfizer–BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine for emergency use in children 5 through 11 years of age. October 29, 2021. (https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-pfizer-biontech-covid-19-vaccine-emergency-use-children-5-through-11-years-age).

- 2.Cohen-Stavi CJ, Magen O, Barda N, et al. BNT162b2 vaccine effectiveness against omicron in children 5 to 11 years of age. N Engl J Med 2022;387:227-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming-Dutra KE, Britton A, Shang N, et al. Association of prior BNT162b2 COVID-19 vaccination with symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in children and adolescents during omicron predominance. JAMA 2022;327:2210-2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price AM, Olson SM, Newhams MM, et al. BNT162b2 protection against the omicron variant in children and adolescents. N Engl J Med 2022;386:1899-1909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin D-Y, Gu Y, Wheeler B, et al. Effectiveness of Covid-19 vaccines over a 9-month period in North Carolina. N Engl J Med 2022;386:933-941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.