Abstract

The viral accessory protein Vpx is required for productive in vitro infection of macrophages by simian immunodeficiency virus from sooty mangabey monkeys (SIVSM). To evaluate the roles of Vpx and macrophage infection in vivo, we inoculated pigtailed macaques intravenously or intrarectally with the molecularly cloned, macrophage tropic, acutely pathogenic virus SIVSM PBj 6.6, or accessory gene deletion mutants ΔVpr or ΔVpx) of this virus. Both wild-type and SIVSM PBj ΔVpx viruses were readily transmitted across the rectal mucosa. A subsequent ‘stepwise’ process of local amplification of infection and dissemination was observed for wild-type virus, but not for SIVSM PBj ΔVpx, which also showed considerable impairment of the overall kinetics and extent of its replication. In animals co-inoculated with equivalent amounts of wild-type and SIVSM Pbj ΔVpx intravenously or intrarectally, the ΔVpx mutant was at a strong competitive disadvantage. Vpx-dependent viral amplification at local sites of initial infection, perhaps through a macrophage-dependent mechanism, may be a prerequisite for efficient dissemination of infection and pathogenic consequences after exposure through either mucosal or intravenous routes.

Replication within cells of the macrophage lineage is a well-established feature of primate lentivirus biology, and macrophage infection has been implicated in various aspects of AIDS pathogenesis1-6. Selection for R5 viruses (monocytotropic, non-syncytium-inducing viruses using the CCR5 co-receptor7) with sexual transmission has been described1-3,and may occur even when the donor virus population contains a large proportion of R4 viruses4,5 (non-monocytotropic, syncytium-inducing viruses7). Vaginal infection of rhesus macaques with a mixture of chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) having either an R4 or an R5 HIV-1 envelope results in selective transmission of viruses containing the R5 envelope gene6.

Efficient replication of HIV-1 and SIVAGM in primary macrophages requires the accessory gene product Vpr8-11, which promotes translocation of the reverse transcription complex to the nucleus8-13. HIV-1 Vpr also induces host cell-cycle arrest14-18, a function that is mechanistically distinct from its role in mediating macrophage infection12,14-18. Members of the HIV-2/SIVSM/SIVMAC lineage encode, in addition to Vpr, a related accessory protein designated Vpx (ref. 19). Site-directed mutagenesis studies demonstrated that loss of Vpx function in SIVSM PBj profoundly impaired the ability of the virus to replicate in primary macaque macrophages, but did not impair replication in pre-activated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or influence host cell cycle12. In contrast, Vpr mutants no longer induced host cell-cycle arrest but were able to replicate in primary macaque macrophages12.

To evaluate the role of macrophage infection and accessory gene function in mucosal transmission and in vivo viral replication, we studied Vpr and Vpx deletion mutants of SIVSM PBj, using the infectious molecular clone SIVSM PBj 6.6 as a representative of the HIV-2/SIVSM group of viruses. Unlike most other HIV-2 and SIVSM clones, SIVSM PBj 6.6 is acutely pathogenic and grows well in macaque macrophages, and thus is well suited for examining the role of macrophage infection in viral transmission and pathogenicity. We did longitudinal measurements of plasma viral load and sequential in situ hybridization analysis in animals inoculated intrarectally (IR) or intravenously (IV) with wild-type (WT) or mutant viruses, and also evaluated the proportional representation of WT and mutant viruses in the plasma virus pool after co-inoculation IV or IR.

Viremia and lymphocyte loss after challenge IR or IV

Each animal inoculated IR with the WT virus (either alone or in combination with mutant virus) developed typical SIVSM PBj infection with characteristic disease symptoms (Table 1), a rapid rise in plasma viremia and an associated decrease in circulating lymphocytes20 (Fig. 1). One of the two macaques inoculated IR with the ΔVpr virus, PT 541 succumbed to disease. The other, PT 547, survived the acute phase of disease; with resolving viremia, circulating lymphocytes rebounded to above preinoculation values. The kinetics of viremia for the ΔVpr mutant virus were delayed slightly relative to those of the WT virus. Macaques inoculated IR with the ΔVpx mutant virus (PT 607 and PT 608) also became infected, but did not show clinical symptoms of the acute disease syndrome, and showed a delayed and blunted plasma viremia peak with only minimal and transient decreases in circulating lymphocytes.

Table 1.

Outcome of inoculation of macaques intravenously (IV) or intrarectally (IR) with SIVSM PBj wild-type (WT), ΔVpx mutant or ΔVpr mutant

| Route | Virus inoculated | Macaque | Peak viremia (copies/ml) |

Survival (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR | WT | PT 526 | 1,200,000 | 9 |

| WT | PT 539 | 36,000,000 | 9 | |

| ΔVpr + WT | PT 610 | 7,800,000 | 10 | |

| ΔVpr + WT | PT 611 | 1,300,000 | 10 | |

| ΔVpx + WT | PT 614 | 7,400,000 | 10 | |

| ΔVpx + WT | PT 615 | 9,700,000 | 12 | |

| ΔVpr | PT 541 | 11,000,000 | 12 | |

| ΔVpr | PT 547 | 3,900,000 | survived | |

| ΔVpx | PT 607 | 2,000 | survived | |

| ΔVpx | PT 608 | 184,000 | survived | |

| IV | WT | PT 123 | 20,000,000 | 6 |

| WT | PT 389 | 6,300,000 | 7 | |

| ΔVpr + WT | PT 618 | 4,000,000 | 7 | |

| ΔVpx + WT | PT 620 | 17,000,000 | 6 | |

| ΔVpr | PT 437 | 5,400,000 | 6 | |

| ΔVpr | PT 453 | 1,200,000 | survived | |

| ΔVpx | PT 537 | 18,000 | survived | |

| ΔVpx | PT 549 | 260,000 | survived |

Fig. 1.

Kinetics of plasma viremia and lymphopenia in macaques inoculated intrarectally with ΔVpr (left graphs: □, 541; ○, 547) or ΔVpx mutants (right graphs: □, 607; ○, 608) or with WT SIVSM PBj (■, 526; ●, 539). Values shown are averages for duplicate determinations on RNA extracted from individual plasma samples.

Macaques inoculated IV with WT virus (either alone or in combination with mutant virus) developed characteristic fulminant SIVSM PBj disease by 6 or 7 days after inoculation, with peak plasma viremia of 106 to 107 copy equivalents per ml (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The kinetics of viremia and disease symptoms were more rapid in onset in the animals inoculated IV (6–7 days) compared with those inoculated IR (9–12 days). As in the IR-inoculated macaques, viremia was accompanied by a profound circulating lymphopenia (Fig. 2). One of the two macaques inoculated IV with the ΔVpr mutant virus (PT 437) developed acute disease; in the other (PT 453), viral RNA values peaked at a slightly lower level, then began to decline, co-incident with clinical recovery and a substantial rebound lymphocytosis. In the macaques inoculated IV with the ΔVpx mutant virus (PT 537 and PT 549), viremia was delayed, and peak levels of plasma viral RNA were approximately 0.1% the levels in macaques infected with the WT virus. No disease manifestations were observed in the macaques inoculated IV with the ΔVpx mutant virus.

Fig. 2.

Kinetics of plasma viremia and lymphopenia in macaques inoculated intravenously with ΔVpr (left graphs: □, 437; ○, 453) or ΔVpx mutants (right graphs: □, 537; ○, 549) or with WT SIVSM PBj (■, 123; ●, 389). Values shown are averages for duplicate determinations on RNA extracted from individual plasma samples.

Tissue analysis: In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

To analyze the role of Vpx and macrophage infection in the early events of mucosal infection at the tissue level, we inoculated a cohort of six macaques IR with either WT virus (n = 3) or the ΔVpx mutant virus (n = 3). One macaque from each group was killed on days 2, 4 and 7 after inoculation, and in situ hybridization analysis for SIV RNA was done on samples of rectal, intestinal and lymphoid tissues (Table 2). Despite daily sampling, plasma viral RNA was detectable only in samples from the WT-inoculated macaques. However local viral RNA expression was readily observed by in situ hybridization analysis in tissues of macaques inoculated with either WT or ΔVpx mutant viruses.

Table 2.

Summary of in situ hybridization results for SIV in tissues of SIVSM PBj -inoculated macaques killed in series

| wild-type | ΔVpx mutant | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4 | 7 days | 2 | 4 | 7 days | |

| Macaque | 609 | 550 | 523 | 616 | 613 | 612 |

| Tissue | ||||||

| Mesenteric LN | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Jejunum | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Ileum | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Ileocecal junction | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Cecum | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Colon | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| Rectum | + | + | + | n.a. | + | + |

| Plasma Viremia | <300 | 2,800 | 310,000 | <300 | <300 | <300 |

n.a., not available.

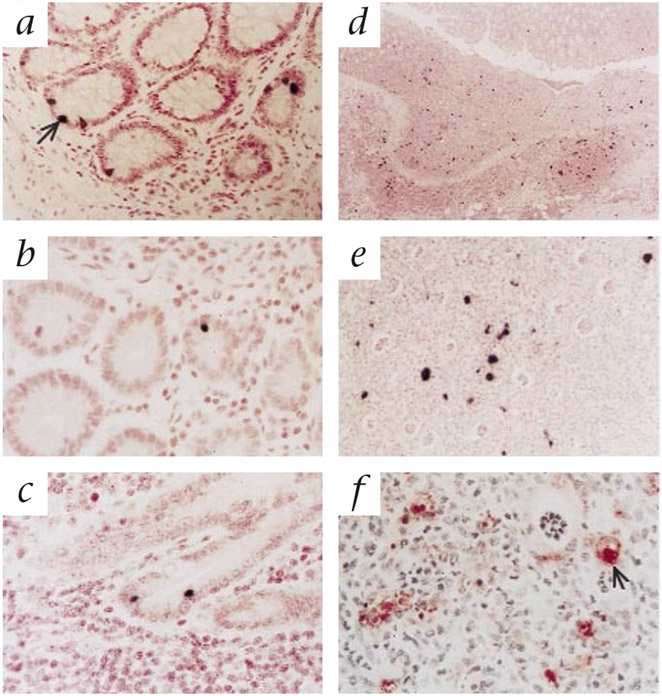

In situ hybridization analysis of sequential tissue specimens in animals inoculated IR with WT virus showed a ‘stepwise’ progression of the infection process. Infection was initially limited and focal, followed by local amplification of infection with recruitment of uninfected cells, formation of characteristic local lesions and dissemination to distant sites. By day 2 after inoculation with WT virus, only scattered individual SIV RNA+ cells were present (Fig. 3a). Morphologically, the infected cells were predominantly intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL), located within the rectal crypt epithelium. SIV RNA+ cells were not detected outside the rectum at this time. By day 4, more SIV-expressing IEL were found, and a focal rectal lesion characteristic of SIVSM PBj pathology was also observed (Fig. 3d and e). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated an influx of macrophages (HAM-56+) into the localized lesion (Fig. 3f), indicating active recruitment of these cells. In contrast, in the rectal sections from macaques inoculated with the ΔVpx virus, SIV RNA+ cells were detected, but there was no evidence of local amplification of infection, recruitment of uninfected macrophages or formation of the characteristic SIVSM PBj-associated lesions. Rectal samples were not available for in situ hybridization from the animal inoculated with SIVSM PBj ΔVpx and killed on day 2 after inoculation because of tissue sampling errors. However, virus-expressing cells were detected in the rectum by day 4 after inoculation with no associated pathology (Fig. 3b). Similar to the day 2-sample from the WT-inoculated macaque, the infected cells were mostly IEL in the rectal crypts and lamina propria. SIV-expressing cells were more readily detected in the rectal samples collected from the SIVSM PBj ΔVpx-inoculated macaque necropsied on day 7, and were occasionally observed at other intestinal sites (Fig. 3c). Thus, transmission of the ΔVpx mutant virus across the rectal mucosa seemed to be relatively efficient, but the early local amplification stage and subsequent systemic dissemination were considerably impaired. The salient influx of macrophages and lymphocytes into the sites of SIV infection seen in the rectum of animals infected with WT virus was also not seen in macaques inoculated with the ΔVpx mutant. SIV-infected cells in the tissues of macaques inoculated with the ΔVpx mutant virus were exclusively CD3 lymphocytes (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Representative SIV-specific in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry for Ham-56 (macrophage marker) in tissues of macaques inoculated intrarectally with either WT SIVSM PBj (a,d–g) or the ΔVpx mutant virus (b and c). a, Intraepithelial lymphocyte (IEL) expressing SIV RNA (arrow) in the rectum of macaque PT550 at 4 days after inoculation with WT virus. b, SIV+ IEL in the rectum of macaque PT612 at 7 days after inoculation with ΔVpx virus. c, SIV+ IEL in the ileum of macaque PT612 at 7 days after inoculation with ΔVpx virus. d, Low magnification in situ hybridization of a characteristic local lesion in the rectum of macaque PT523 at 7 days after inoculation with WT virus, showing local infiltration of lymphocytes and macrophages with many SIV-expressing cells. e, Higher magnification of the localized rectal lesion shown in d. f, High magnification of immunohistochemical staining for HAM-56 expression in rectal lesion in macaque PT523, inoculated with WT virus, showing infiltration of macrophages (arrow) into the lesion.

Double labeling for SIV-expression in combination with either CD3 or Ham56 was used to identify the early and late cellular targets in SIVSM PBj infection (Fig. 4). SIV-expressing CD3 lymphocytes were observed in the early rectal lesions (Fig. 4g-i). SIV-infected macrophages were not identifiable in early rectal lesions but were presumed to be present at a low frequency, as they were readily identified in rectal samples collected from macaques at the time of peak viremia, when the number of virus expressing cells was maximal (Fig. 4d-f). Even at these late time points, only 10% of the infected cells seemed to be macrophages (Fig. 4a-c). The data indicate that after mucosal exposure, SIV must replicate locally before widespread virus dissemination, consistent with the observed delay in plasma viral RNA kinetics after intratrectal inoculation relative to intravenous challenge (Figs. 1 and 2).

Fig. 4.

Double labeling for SIV expression and cell surface expression of CD3 or Ham56 (macrophage) in rectal sections collected at peak viremia, demonstrating both SIV-infected T lymphocytes (top row, a–c) and macrophages (middle row, d–f). a and d, cell surface marker (green fluorescence); b and e, SIV expression (green); c and f double exposure or the same field showing double-labeled cells (yellow). Approximately 90% of SIV-expressing cells at this time point were identified as CD3+ T cells. Bottom row (g–i), SIV-infected T lymphocytes on the same field of a rectal sample on day 4 after intrarectal exposure. g, CD3+ cells (green); h, SIV-infected cells (red); i, SIV-infected T lymphocytes (yellow).

Co-infection analysis of relative viral fitness

Based on plasma viral RNA measurements, the extent and kinetics of in vivo replication of the ΔVpx mutant virus seemed to be severely impaired, whereas the ΔVpr mutant virus seemed to be modestly impaired, relative to the WT SIVSM PBj virus. However, as viral replication kinetics can vary between macaques inoculated identically with the same virus11,21,22, we evaluated the relative in vivo competitive fitness of WT and mutant viruses by doing co-infection studies. This approach should be more representative of the situation during HIV-1 infection in which the donor virus pool contains a mixture of virus variants of varying properties1-3,24. At various times after inoculation, appropriate vpr and vpx genomic regions were amplified from plasma virions by nested RT–PCR, cloned, and the proportional representation of WT and mutant genomes in the cloned population were determined by differential oligonucleotide hybridization (Fig. 5a). This approach allowed the relative competitive ‘fitness’ of WT and mutant virus to be evaluated under identical in vivo circumstances in the same host, thus eliminating as a potential confounding factor any inherent differences between animals in their capacity to support viral replication.

Fig. 5.

Replication and proportional representation of SIVSM PBj WT, ΔVpr and ΔVpx mutant viruses after intravenous or intrarectal co-inoculation. a, Identification of WT, Δvpr and Δvpx genotypes by differential oligonucleotide hybridization. Bacterial colonies transformed with WT, ΔVpr and ΔVpx SIVSM PBj molecular clones (genotype) were hybridized with probes recognizing WT, Δvpr or Δvpx sequences or with a common probe that hybridizes to both WT and mutant genomes. Hybridization conditions were adjusted to promote specific binding of each probe to its cognate sequence. b and c, Proportional representations of WT, ΔVpr and ΔVpx variants of SIVSM PBj in plasma after intravenous (b) or intrarectal (c) co-inoculation. The relative proportions of WT and mutant genomes were determined by differential oligonucleotide probe hybridization and are shown as mutant genotype fraction. Absolute plasma RNA copy numbers for WT and mutant genomes were calculated on the basis of the measured total (WT and mutant) plasma SIV RNA copy number and the percentages of WT and mutant genotype determined by differential probe hybridization at each indicated time point.

We assessed the relative frequencies of WT, ΔVpr and ΔVpx mutant genomes in plasma after co-inoculation IV (Fig. 5b). All macaques received a mixture of equal proportions of WT and the appropriate mutant virus. In PT 618, the ΔVpr and WT virions were represented in plasma in approximately equal proportions at 24 hours after inoculation, although the frequency of ΔVpr mutant genomes declined to 35% of total plasma virions by days 2 and 3, consistent with a slight relative advantage of the WT virus. In contrast, in PT 620, which received a mixture of WT and ΔVpx mutant viruses, the WT virus was over-represented even at 24 hours (70% WT and 30% ΔVpx), and the frequency of the ΔVpx mutant virus was further reduced to only 1–2% of total plasma virions by day 4 after inoculation. It is unlikely that these proportions of viral genotypes in the plasma samples at early time points represent residual virions from the inoculation, as the half-life for clearance of infused SIV virions from plasma is extremely rapid, on the order of 10 minutes24. Because the rate of virus expansion between days 1 and 4 was exponential, the observed decline in proportion of ΔVpx mutant virus actually represents a slight absolute increase in the total number of ΔVpx mutant genomes present.

We also determined the relative proportions of WT and mutant virions present at various times after inoculation IR. In each of the animals, the mutant viruses could be detected simultaneously with WT virions, which indicated successful initial transmission across the rectal mucosa. However, WT genotypes were over-represented relative to the ΔVpr mutant genotypes (77% WT and 23% ΔVpr for PT610; 92% WT and 8% ΔVpr for PT611) by the earliest time that plasma viral RNA could be quantified (day 4)(Fig. 5c). The proportions of WT virus to ΔVpx mutant genotypes in macaques co-inoculated with WT and ΔVpx showed a far more profound skewing towards a predominance of WT virus (97% WT and 3% ΔVpx for PT614; >99.9% WT and 0.1% ΔVpx for PT615). The kinetics of viremia in the second of these macaques (PT615) were slightly delayed relative to other macaques inoculated with WT virus.

In the macaques co-inoculated with WT and mutant viruses either IV or IR, the replication kinetics of both WT and mutant viruses, which were calculated on the basis of the relative proportions of each virus and total viral RNA levels, were indistinguishable from those observed in macaques inoculated with ΔVpx or WT virus alone (Figs. 1, 2 and 5b and c). Thus, there were no obvious apparent interactions between the co-inoculated viruses; the presence of the mutant viruses did not seem to interfere with or potentiate replication of the WT virus, or vice versa. In ΔVpr-infected animals, the extent of virus replication, including the kinetics of viremia and virus load, seemed similar to that in WT-infected macaques. However, in the setting of co-infection, a greater competitive disadvantage of the ΔVpr virus was demonstrated (Figs.1, 2 and 5b and c). Thus, those properties associated with SIVSM Vpr, including cell-cycle arrest12 and association with the DNA repair enzyme uracil DNA glycosylase25,26, seem to promote selective growth advantage in virus replication. This growth advantage, however, seems to be modest in comparison with the substantial attenuation of the ΔVpx mutant, both in the setting of single infection and in the context of co-infection.

Discussion

Previous studies suggested that initial infection of macrophages is required for mucosal transmission of SIV or HIV-1. The first infected cells identified after mucosal inoculation of SIV were apparently of the macrophage lineage27, consistent with the apparent preferential selection of R5 viruses after mucosal transmission of HIV-1 (ref. 28). We initiated this study based on the hypothesis that rectal transmission is mediated through initial infection of macrophage lineage cells. Given the inability of the ΔVpx virus to productively infect macrophages in vitro, the ΔVpx mutant virus would be expected to replicate with essentially WT kinetics after exposure IV, but would be expected to be substantially impaired for initial infection after exposure IR. Our results contradict this hypothetical expectation in many ways.

The main unexpected observation was that the ΔVpx mutant virus was readily transmitted across the rectal mucosa. In situ hybridization analysis showed SIV-RNA+ cells localized to the rectum within a few days after inoculation,and the ΔVpx virus was detected in the plasma by the time of first detection of WT virus in macaques co-inoculated with WT and ΔVpx viruses. However, both the overall extent and kinetics of replication of the ΔVpx mutant virus were profoundly impaired relative to WT virus. This was true after inoculation either IR or IV.

The deficit in the ΔVpx mutant virus seemed to be in the efficiency of viral spread, rather than a defect in the ability to mediate initial infection or an impairment in the inherent replicative capacity of the virus. Thus, once measurable levels of viral RNA were present in the plasma of ΔVpx-infected animals, the slope of increase in plasma viral RNA levels was similar to the slope for WT virus. However, the onset to measurable plasma viremia was delayed and the peak levels of plasma viremia were also considerably decreased relative to infection with WT virus. Also in contrast to expectations, the ΔVpx virus was equally impaired after exposure either IV or IR. Finally, the apparent initial cellular targets differed from the prediction that infection of macrophages and dendritic cells would be required for mucosal transmission. Both WT and ΔVpx viruses were readily transmitted across the rectal mucosa, and in both cases, the infected cells were predominantly intraepithelial lymphocytes.

Sequential in situ hybridization analysis of tissues allowed us to observe an apparent ‘stepwise’ progression in the early infection process. Initially, rare individual SIV-infected cells were detected in the rectum. This was followed by local amplification of the infection with recruitment of uninfected cells, and the local development of characteristic pathological lesions and the subsequent distant dissemination of virus throughout the gastrointestinal tract and lymphoid tissues, with the associated onset of widespread pathology. A requirement for a local replication and amplification phase before systemic dissemination of virus in mucosally infected animals would explain the observed lag period for the appearance of quantifiable plasma viremia in mucosally inoculated macaques compared with animals inoculated IV, as has been seen in other SIV/macaque model systems29,30.

In macaques challenged IR with the ΔVpx mutant, although the initial appearance of SIV-expressing cells in the rectum was similar to that of the WT-inoculated macaques, the subsequent steps were considerably impaired. Analysis of WT-inoculated animals at the peak of viremia indicated the presence of infected macrophages in rectal lesions (Fig. 4). However, macrophages represented a minority of the infected cell population. No SIV-RNA+ macrophages were observed in the animals that received the ΔVpx mutant virus. This does not preclude the possibility that such cells were present at an extremely low frequency, given the intrinsic sampling limitations of in situ hybridization and the low frequency of infected macrophages even in WT-inocu lated macaques. However, the results indicate the potentially essential participation of the Vpx protein in the establishment of pathogenic SIV infection in a role that extends beyond the initial entry of virus. Similarly, infection of Langerhans cells, which express both CCR5 and CXCR4 (ref. 31), may promote an environment for dissemination of infection rather than promote actual transmission.

The Vpx protein, although not absolutely required for AIDS pathogenesis in some systems32, does seem to have an essential role in early virus dissemination after inoculation of SIV either IV or IR. Our results here indicate a central but indirect role for Vpx and, by implication, infected macrophages, in the processes of local amplification of virus replication and recruitment of uninfected cells, which seems to be required for efficient virus dissemination after mucosal challenge. Secretion of soluble mediators by infected macrophages during the earliest stages of infection could contribute to the recruitment of uninfected cells, local amplification of infection and lesion formation that seem to be necessary antecedents to peripheral dissemination and disease induction. In support of this, HIV-1 infected macrophages express increased levels of β-chemokines33, which may promote the chemotactic recruitment of lymphocytes to sites of infection (Swingler, S. et al., in preparation). A prediction of this model is that a very low number of infected macrophages could, through the release of β-chemokines, promote the recruitment and infection of many T-cells, thus contributing to local viral amplification.

Could the ΔVpx defect be a T cell-mediated phenomenon? SIVSM PBj has been considered atypical because its gene contains a Nef allele that confers on the virus the ability to activate and replicate within unstimulated lymphocyte cultures. This property of SIVSM PBj, however, depends on the presence of macrophages, and lymphocyte activation by this virus is abrogated when macrophages are removed from the culture34. Mutations in Vpx also eliminate the ability of SIVSM PBj to replicate within unstimulated lymphocyte cultures(B.B. et al., unpublished observations). Presumably, infection of macrophages by SIVSM PBj creates conditions that promote co-stimulation of uninfected T cells or release of chemoattractants that augment T-cell activation. This, therefore, indicates that mutations in Vpx that impair macrophage infection ultimately restrict the ability of SIVSM PBj to activate and replicate within lymphocytes. Macrophage-dependent lymphocyte activation probably is not characteristic of SIVSM PBj. Unstimulated PBMC cultures can also support HIV-1 replication, if macrophages are present35,36. SIVSM PBj thus probably constitutes one extreme of a spectrum of viral phenotypes, differing quantitatively rather than qualitatively from other primate lentiviruses in its ability to mediate lymphocyte activation and related phenomena that may be important contributors to general mechanisms of pathogenesis. The inability of the ΔVpx mutant virus to infect macrophages, and the resulting lack of activating stimuli might result in a lack of recruitment of uninfected cells, and failure of local amplification of viral replication in these animals. This inability to exploit macrophages for dissemination of viruses to T-cells probably forms the basis for the impaired replication of the ΔVpx mutant after inoculation IV. Given the very rapid clearance of virions from the circulation26, it is likely that the spread of viruses through cell–cell contact is less sensitive to viral clearance mechanisms of the host. In addition, the ability of the virus to exploit macrophage-mediated T-cell activation provides an efficient conduit to permissive T cells, not unlike that described for conjugates of T cells and dendritic cells37. Differences in the in vivo replication properties of WT and ΔVpx mutant viruses may thus reflect differences in the efficiencies of virus dissemination through pathways that do and do not include mechanisms dependent on infected macrophages.

Individuals with homozygous deletions in the CCR5 gene are very resistant to HIV-1 infection, despite multiple exposures38. Macrophages from such individuals are refractory to HIV-1 infection in vitro by viruses with R5 tropism. However, PBMCs from these individuals maintain CXCR4 co-receptor expression and can be infected in vitro by R4 viruses38,39. Although SIV isolates use CCR5 and other co-receptors, and do not seem to use CXCR4 (ref. 40), the evidence here, where restriction of target cell tropism is presumably operative at a post-entry level, indicates that the inability to productively infect macrophages in vivo might compromise local virus amplification and dissemination from initial sites of infection. If, as these studies suggest, macrophages are necessary for efficient establishment and dissemination of infection, then these cells may represent essential targets in the design of strategies that interfere with virus replication in the host.

Methods

Intravenous and mucosal infection.

All animal studies were done in accordance with the guidelines of the NIH Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The study animals were juvenile pigtailed macaques (Macaca nemestrina) that were free of concurrent infections with either type D simian retrovirus (SRV) or simian T-cell leukemia virus (STLV-1), and they ranged in body weight from 5 to 8 kg. While sedated by ketamine anesthesia, macaques were inoculated either IV or IR with 2,000 tissue culture infectious doses 50% (TCID50) of each of the respective viruses as determined by limiting dilution infectivity titration in the susceptible cell line, CEMx174. Intrarectal inoculation was done without trauma to the animals by instilling the virus inoculum (1 ml total volume) in the rectum using a soft, flexible feeding tube. For co-infection studies, 2,000 TCID50 each of the WT and mutant virus were simultaneously co-inoculated. All subsequent manipulations, such as blood collection, were done on animals sedated by ketamine anesthesia.

Production and characterization of viruses.

The infectious molecular clone SIVSM PBj 6.6 was used as the starting virus for mutational studies because of its known acute pathogenic phenotype in macaques infected experimentally41. In contrast to PBj 1.9, which causes relatively mild clinical symptoms42, PBj 6.6 generally causes an acute lethal syndrome, characterized by severe lymphopenia, diarrhea, dehydration, lethargy, rash and fever, which generally leads to death of the infected animals within a week after inoculation41. To study the roles of Vpx and Vpr in this accelerated disease model, we thus introduced the vpx- and vpr-inactivating mutations described for PBj 1.9 (ref. 12) into PBj 6.6. This was done by exchanging an internal BclI/SacI fragment (1193 bp), which contained the PBj 1.9 X2 and R2 mutations, with the corresponding fragment of SIVSM PBj 6.6. This resulted in the constructs PBj 6.6 X2 and R2 that were identical to those described for PBj 1.9 (ref. 12) in their vpx- and vpr-inactivation mutations; no additional changes were introduced, as the nucleotide sequences of PBj 1.9 and PBj 6.6 are otherwise identical in the BclI/SacI fragment. Sequences of the vpx and vpr regions of the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis. As in PBj 1.9, none of the PBj 6.6 vpx or vpr mutations resulted in amino-acid changes in overlapping reading frames. The resulting clones, called PBj 6.6 X2 and R2, were then characterized for their ability to replicate in CEMx174 cells, primary macaque PBMCs and macrophages. As shown for PBj 1.9 (ref. 12), the PBj 6.6 Vpx protein was not required for growth in previously activated primary macaque PBMCs or CEMx174 cells, but was essential for productive infection of macrophages or resting PBMCs (B.B. et al., unpublished). Similarly, the PBj 6.6 Vpr was dispensable for growth in macrophages and activated or resting PBMCs, as well as CEMx174 cells (data not shown). The PBj 6.6 X2 and R2 mutants thus had in vitro phenotypes identical to those of PBj 1.9 (ref. 12).

Plasma viral load measurements, lymphocyte subsets and tissue analysis.

EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples were collected daily for measurement of plasma viral load and PBMC separation. Plasma viral RNA was measured using a QC–RT–PCR assay43 or a real-time RT–PCR assay44 as described. The nominal threshold sensitivities were 400 copy equivalents/ml (Eq/ml) for the QC–RT–PCR (used for the intravenous inoculation studies) and 300 Eq/ml assay for the real time RT–PCR assay (used for the intrarectal inoculation studies and studies in which macaques were killed in series). Both assays had an interassay coefficient of variation of less than 25%. Hematologic alterations were evaluated daily, and lymphocyte subsets (CD2, CD4, CD8 and CD20) were evaluated by flow cytometric analysis on days 0, 3, 7, 10 and 14 as well as on the day the animal was killed. The animals were killed by exsanguination while sedated by deep anesthesia if they demonstrated complete anorexia, diarrhea, 5 to 10% dehydration and moderate depression in conjunction with severe lymphopenia. The five macaques that survived the acute phase of the disease were subsequently killed within a month of challenge. An additional group of six macaques was inoculated IR with WT or ΔVpx mutant virus and plasma samples collected daily as described above. At days 2, 4 and 7, one each of the WT-inoculated and ΔVpx mutant-inoculated macaques was killed and a complete pathologic examination was done.

In situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry.

Tissues were analyzed for SIV expression using in situ hybridization (Fig. 4) with digoxigenin-labelled probes that span the entire SIVmac 239 genome, as described10,20. Paraffin sections of formalin-fixed tissues were double-stained for SIV antigen and CD3 (Dako, Carpinteria, California) or HAM-56, a macrophage-specific antibody (Dako, Carpinteria, California). An antibody against whole SIVmneE11S (supplied by L. Henderson and R. Benveniste) was used to detect SIV-infected cells in the tissue samples. Tissue sections on sialinated slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated into PBS before a 2-min treatment in a boiling solution of 0.01 M sodium citrate buffer, pH 6.0, in a pressure cooker. The samples were subsequently rinsed in PBS and digested with ProteaseVIII (Sigma) for 3 min at 37 °C, then rinsed in PBS–glycine for 5 min and blocked with 1% non-fat milk, 3% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California) and 0.5% bovine serum albumin (Sigma) for 1 h. Double labeling for SIV (1:250 dilution) and Ham56 (1:75 dilution) were done simultaneously in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Tissue sections incubated with anti-SIV-E11S and HAM-56 (macrophage antibody) were stained initially with GAR-IgG–biotin and streptavidin-FluorLink Cyan 3 as described above, and then goat anti-mouse-IgM–biotin and streptavidin-FluorLink Cyan 2. These samples were rinsed and coverslipped with 20% glycerol in PBS. Double labeling for SIV and CD3 was done by incubation initially with anti-SIV (1:250 dilution) in PBS for 1 h at room temperature, after which samples were rinsed in PBS and stained with goat anti-rabbit-IgG-biotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California) for 30 min at room temperature, rinsed in PBS, then incubated in streptavidin-FlouroLink Cyan 3 (1:150 dilution; Amersham/Pharmacia Biotech) in 0.1 M Tris buffer, pH 7.4. The stained samples were rinsed in Tris buffer containing 0.01% Tween-20 and then incubated in the second primary antibody, anti-CD3 (1:100 dilution) for 1 h at room temperature. The samples were rinsed in PBS, and then incubated in goat anti-rabbit-IgG–biotin (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, California), rinsed in PBS, and then incubated in streptavidin-FluorLink Cyan 2 (1:150 dilution). The double-stained samples were thoroughly rinsed in 0.1 M Tris and coverslipped with 20% glycerol in PBS. All cyan dye-stained samples were viewed on a Zeiss Axiophot microscope equipped with a 100W mercury bulb, FITC and rhodamine filters, and 40× or 63× Planapo oil immersion objectives. Double-stained cyan dye sections were examined with each UV filter to detect SIV infected cells (CY3, red) and CD3 or HAM-56 (CY2, green) positive cells. Double exposure of one frame of film (Ektachrome 200) with each UV filter sequentially, captured images of double-stained cells (yellow) in each sample.

Characterization of viral genotypes in plasma.

Plasma was clarified by centrifugation at 2800g for 10 min at 4 °C, and genomic RNA was isolated (with 50 μg of glycogen as a carrier) using Tri-reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio). RNA precipitates were resuspended in 20 μl of RNase-free water containing a 1:4 dilution of RNase inhibitor (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Connecticut) and stored in 2 μl aliquots at −70 °C. cDNA synthesis was done with MuLV reverse transcriptase (Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Connecticut) for 25 min at 44 °C using a vpr-specific primer (PBj R2: 5′–GGGTGTCTCCATGTCTATCATA–3′). Part of the cDNA synthesis reaction (10%) was amplified by nested PCR. The region encompassing both vpr and vpx genes was amplified using a reverse PBj R2 primer and a forward PBj X2 primer (from nt 5523: 5′–GCTCATAAGAATCAGGTACC–3′). After initial denaturation (95 °C, 2 min), cDNA products were amplified using Amplitaq DNA polymerase and Taqstart antibody (Clontech, Palo Alto, California) for between 13 and 35 cycles of PCR amplification (95 °C for 30 s; 58 °C for 30 s; 72 °C for 60 s) followed by a single extension (72 °C for 5 min). The number of cycles was adjusted to yield a sufficient amount of amplified product for cloning purposes. For samples taken at early time points, when virus loads were low, PCR products were amplified in a ‘step’ program using Amplitaq Gold polymerase. 2 μL of first-round PCR products were amplified with Vent DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs) using a forward PBj X2 primer and a nested reverse primer (from nt 5995: 5′–CTCCAGAACTTCTACTACCCATT–3′) in 20–45 cycles at 95 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 1 min, followed by a single extension at 72 °C for 5 min.

Amplified cDNA products were purified (QIAquick PCR purification kit; Qiagen, Valencia, California) and cloned in a PCR-Script cloning vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, California). XL-1 blue MRF-Kan cells were transformed, and colonies were transferred to nylon membranes (Magna Lift; Micron Separation, Westboro, Massachusetts) and disrupted after successive treatment with 10% SDS (3 min), 0.5 N NaOH/1.5N NaCl (5 min), 0.5 M Tris-HCl pH 8.0/1.5 M NaCl (5 min) and 2X SSPE for 5 min. Nucleic acids were bound to membranes using ultraviolet irradiation (Strata Linker; Stratagene, La Jolla, California) and hybridized with 5′ [γ-32P]-ATP end-labeled oligonucleotide probes specific for regions of SIVSM vpr and vpx genes that were mutated in ΔVpr and ΔVpx viruses. Probe sequences were: WT vpr, from nt 5920: 5′–GACAGAAAGACCTCCAG–3′; mutant vpr, from nt 5920: 5′–TACATAATGACCTCCAG–3′; WT vpx, from nt 5809: 5′–TGAGCCATGTCAGATC-3′; mutant vpx, from nt 5809: 5′–GTGAGCCACGTAAGATC–3′. In addition, a common probe (from nt 5680: 5′–CAGCAGTGAATCATTTGCC–3′), which hybridized to sequences outside of the mutagenized regions, was used to identify all recombinant clones. Mismatched nucleotides are indicated in bold, and residues are numbered according to published SIVSM PBj sequences45. Filters were hybridized in a solution containing 5X SSC, 1x Denhardt′s reagent, 0.1% SDS for 16 h at 37 °C. Hybridized filters were washed in 3M tetramethylammonium chloride, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.2% SDS for 15 min at room temperature and then at 52 °C for 1 h. Membranes were then washed twice in a solution of 2X SSC, 0.1% SDS for 10 min at room temperature. Hybridized colonies were visualized on a molecular phosphorimager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, California). For subsequent probe hybridizations, membranes were ‘stripped’ in a solution of 0.4 N NaOH for 30 min at 45 8C, then in a solution of 0.2 M Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.1X SSC, 0.1% SDS for 15 min at 45 °C.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank S. Mc Pherson (UAB CFAR Protein Expression Core) for construction of the PBj 6.6 X2 and R2 clones, and T. Wiltrout and G. Vasquez for technical assistance with viral load analyses. This research was supported in part by grants AI37475, HL57880 and RR11589 (MS) and AI34748 and U01 AI 35282 (BHH) and with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under Contract No. NO1-CO-56000.

References

- 1.Wolfs TFW, Zwart G, Bakker M & Goudsmit J HIV-1 genomic RNA diversification following sexual and parenteral virus transmission. Virology 189, 103–110 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keet IPM et al. Predictors of rapid progression to AIDS in HIV-1 seroconverters. AIDS 7, 51–57 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhu T et al. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 in patients with primary infection. Science 261, 1179–1181 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roos MTL et al. Viral phenotype and immune response in primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J. Infect. Dis 165, 427–432 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nielsen C, Pedersen C, Lundgren JD & Gerstoft J Biological properties of HIV isolates in primary HIV infection: consequences for the subsequent course of infection. AIDS 7, 1035–1040 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu L et al. Vaginal transmission of chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency viruses in rhesus macaques. J. Virol 70, 3045–3050 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger EA et al. A new classification for HIV-1. Nature 391, 240 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heinzinger N et al. The Vpr protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 influences nuclear localization of viral nucleic acids in nondividing host cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91, 7311–7315 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailliet JW et al. Distinct effects in primary macrophages and lymphocytes of the human immunodeficiency virus type I accessory genes vpr, vpu and nef: mutational analysis of a primary HIV-1 isolate. Virology 200, 623–631 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connor RI, Chen BK, Choe S & Landau NR Vpr is required for efficient replication of human immunodeficiency virus type-1 in mono-nuclear phagocytes. Virology 206, 935–944 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell BJ & Hirsch VM Vpr of simian immunodeficiency virus of African green monkeys is required for replication in macaque macrophages and lymphocytes. J. Virol 71, 5593–5602 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher TM et al. Nuclear import and cell cycle arrest functions of the HIV-1 Vpr protein are encoded by two separate genes in HIV-2/SIMSM. EMBO J. 15, 6155–6165 (1996). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vodicka MA, Koepp DM, Silver PA & Emerman M HIV-1 Vpr interacts with the nuclear transport pathway to promote macrophage infection. Genes Dev. 12, 175–185 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.He J et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 viral protein R (Vpr) arrests cells in the G2 phase of the cell cycle by inhibiting p34cdc2 activity. J. Virol 69, 6705–6711 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jowett JBM et al. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene arrests infected T cells in the G2 + phase of the cell cycle. J. Virol 69, 6304–6313 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Re F, Braaten D, Franke EK & Luban J Human immunodefciency virus type 1 Vpr arrests the cell cycle in G2 by inhibiting the activation of p34cdc2-cyclin B. J. Virol 69, 6859–6864 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogel ME, Wu LI & Emerman M The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 vpr gene prevents cell proliferation during chronic infection. J. Virol 69, 882–888 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stivahtis GL, Soares MA, Vodicka MA, Hahn BH & Emerman M Conservation and host specificity of Vpr-mediated cell cycle arrest suggest a fundamental role in primate lentivirus evolution and biology. J. Virol 71, 4331–4338 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sharp PM, Bailes E, Stevenson M, Emerman M & Hahn BH Gene acquisition in HIV and SIV. Nature 383, 586–587 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fultz PN & Zack PM Unique lentivirus-host interactions: SIVSMMPBj14 infection of macaques. Virus Research 32, 205–225 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lifson JD et al. The extent of early viral replication is a critical determinant of the natural history of simian immunodeficiency virus infection. J. Virol 71, 9508–9514 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson A et al. Plasma viremia in macaques infected with simian immunodeficiency virus: plasma viral load early in infection predicts survival. J. Virol 71, 284–290 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wolinsky SM et al. Selective transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variants from mothers to infants. Science 255, 1134–1137 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang L et al. Rate of SIV particle clearance in rhesus macaques in 5th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (Chicago, Illinois 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sleigh R, Sharkey M, Newman MA, Hahn B & Stevenson M Differential association of uracil DNA glycosylase with SIVSM Vpr and Vpx proteins. Virology 245(1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selig L et al. Uracil DNA glycosylase specifically interacts with Vpr of both human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and simian immunodeficiency virus of sooty mangabeys, but binding does not correlate with cell cycle arrest. J. Virol 71, 4842–4846 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spira AI et al. Cellular targets of infection and route of viral dissemination after an intravaginal inoculation of simian immunodeficiency virus into rhesus macaques. J. Exp. Med 183, 215–225 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reece JC et al. HIV-1 selection by epidermal dendritic cells during transmission across human skin. J. Exp. Med 187, 1623–1631 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller CJ Mucosal transmission of simian immunodeficiency virus. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol 188, 107 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desrosiers RC et al. Macrophage-tropic variants of SIV are associated with specific AIDS-related lesions but are not essential for the development of AIDS. Am. J. Pathol 139, 29–35 (1991). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zaitseva M et al. Expression and function of CCR5 and CXCR4 on human Langerhans cells and macrophages: implications for HIV primary infection. Nature Med. 3, 1369–1375 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gibbs JS et al. Progression to AIDS in the absence of a gene for vpr and vpx. J. Virol 69, 2378–2383 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmidtmayerova H et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection alters chemokine ? peptide expression in human monocytes: implications for recruitment of leukocytes into brain and lymph nodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 700–704 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Du Z et al. Identification of a nef allele that causes lymphocyte activation and acute disease in macaque monkeys. Cell 82, 655–674 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mann DL, Gartner S, LeSane F, Buchow H & Popovic M HIV-1 transmission and function of virus-infected monocytes/macrophages. J. Immunol 144, 2152–2158 (1990). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrier RD, McCutchan A & Wiley CA Mechanisms of immune activation of human immunodeficiency virus in monocytes/macrophages. J. Virol 5713–5720 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pope M et al. Conjugates of dendritic cells and memory T lymphocytes from skin facilitate productive infection with HIV-1. Cell 78, 389–398 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu R et al. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell 86, 367–377 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu L et al. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1, in vitro. J. Exp. Med 185, 1681–1691 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marx PA & Chen Z The function of simian chemokine receptors in the replication of SIV. Sem. Immunol 10, 215–223 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Novembre FJ et al. Multiple viral determinants contribute to pathogenicity of the acutely lethal simian immunodeficiency virus SIVSMM PBj variant. J. Virol 67, 2466–2474 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Israel ZR et al. Early pathogenesis of disease caused by SIVSMM PBj14 molecular clone 1.9 in macaques. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 9, 277–286 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hirsch VM et al. Patterns of viral replication correlate with outcome in simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-infected macaques: Effect of prior immunization with a trivalent SIV vaccine in modified vaccinia virus Ankara. J. Virol 70, 3741–3752 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suryanarayana K, Wiltrout TA, Vasquez GM, Hirsch VM & Lifson JD Plasma SIV RNA viral load by real time quantification of product generation in RT PCR. AIDS Res. Hum. Retroviruses 14, 183–189 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dewhurst S, Embretson JE, Anderson DC, Mullins JI & Fultz PN Sequence analysis and acute pathogenicity of molecularly cloned SIV. Nature 345, 636–640 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]