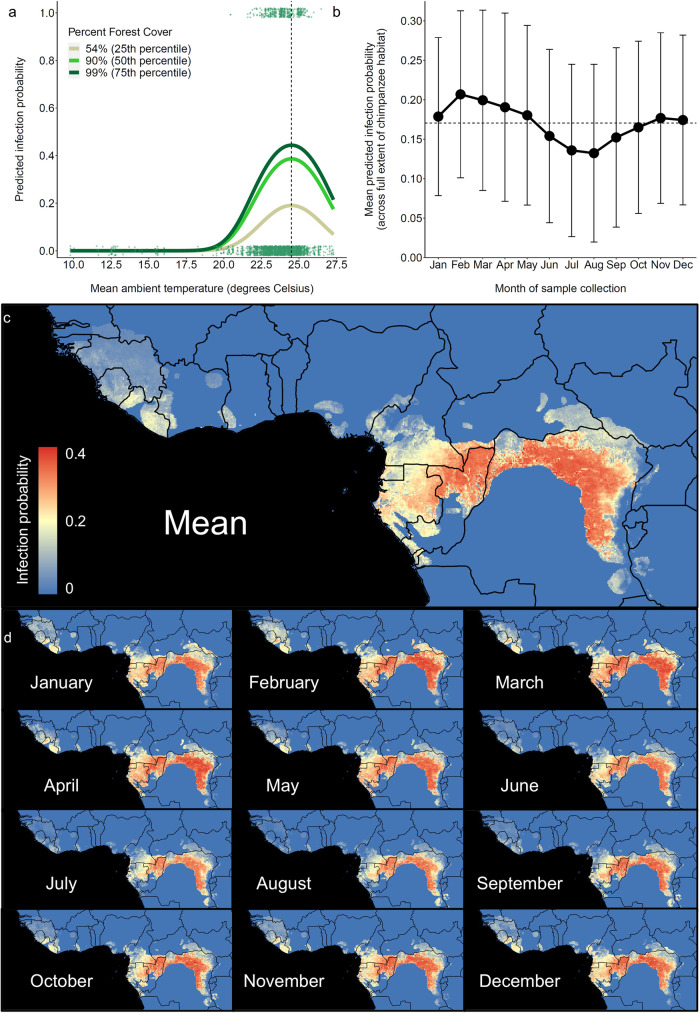

Fig. 5. Ecological niche modeling of malaria parasitism in wild chimpanzee reservoirs across equatorial Africa.

a Analysis of N = 2436 wild chimpanzee fecal samples collected from 55 sampling sites across equatorial Africa demonstrate that mean ambient temperature (inferred from MODIS remote sensing datasets; see Methods) and forest cover62 are critical determinants of chimpanzee Laverania epidemiology. The pan-African GLMM (Table 3) demonstrates that (1) infection probability peaks ~24.5 °C (dotted vertical line), consistent with the empirical transmission optimum of P. falciparum27, and (2) forest cover is positively correlated with infection probability (p = 0.001), consistent with the observation that forest-dwelling Anophelines constitute the primary vectors of these parasites16,17. Color corresponds to three categories of forest cover: 54% (25th percentile), 90% (50th percentile), and 99% (75th percentile). Raw data (binary) are plotted as dots and stratified vertically for visualization. b, c Given the ecological relationships identified in this study, we extrapolated infection probabilities across chimpanzee habitat in equatorial Africa. We derived composite rasters from mean ambient temperature and intra-day temperature variation measurements recorded between 2000 and 2017 across the African continent. Using these composite temperature rasters and the Hansen et al.62 forest cover dataset, we projected the predicted probabilities of chimpanzee Laverania infection (derived from the pan-African model) across the spatial extent of chimpanzee habitat. The monthly mean pixel value of each raster is plotted, and error bars correspond to standard deviation of pixel values on each raster. d Stratification by month highlights the seasonality of these infections. Across chimpanzee habitat, infection probability peaks between the months of January and May, and infection probability declines between June and September. Because mosquito vectors of ape malaria parasites readily bite humans17, these maps can serve as a baseline proxy for spatiotemporal variation in the risk of human exposure in areas where humans and apes overlap.