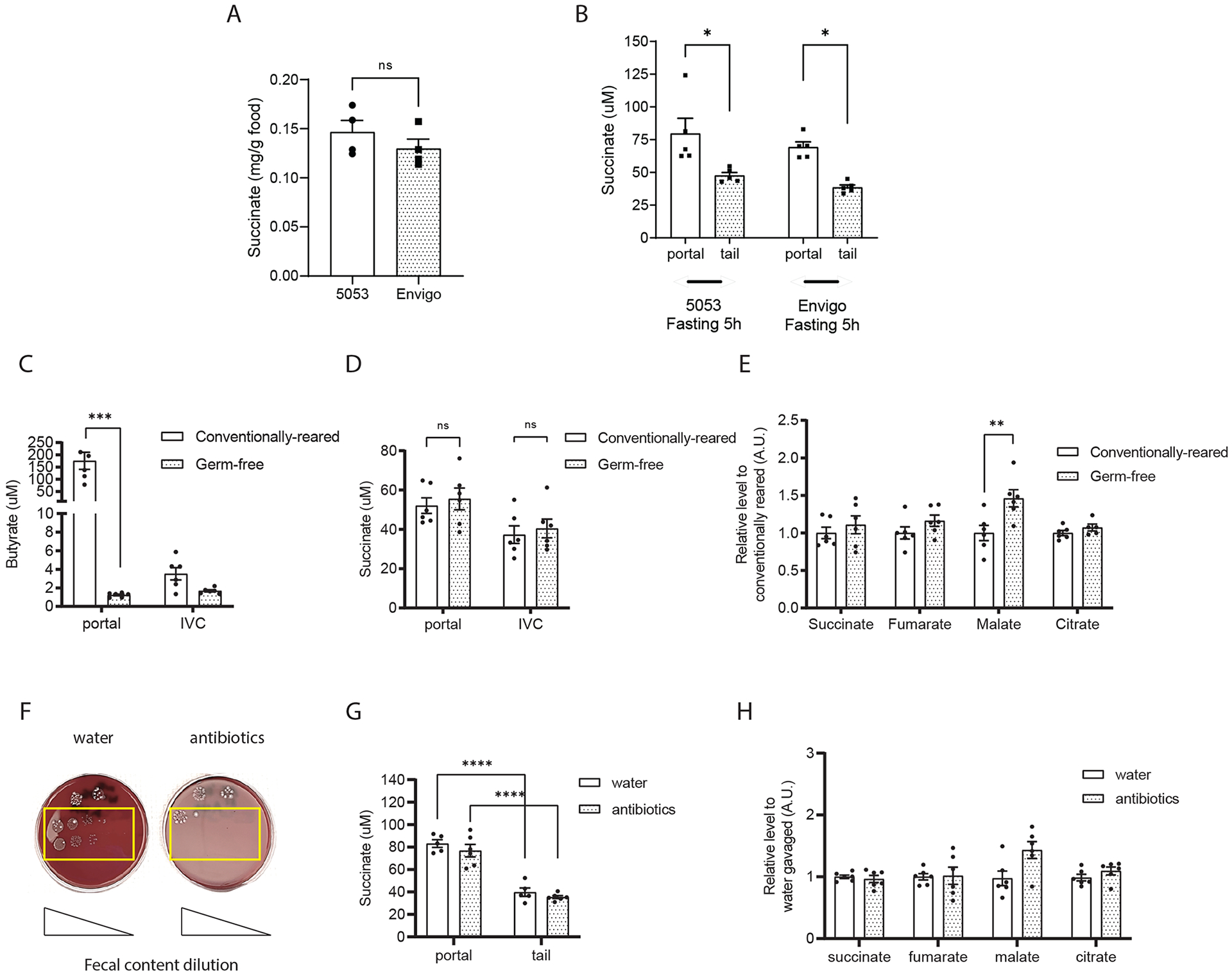

Figure 3. Intestinal microbiota are not a major source of circulating succinate.

(A) Succinate content in normal chow diets: Lab Diet 5053 (conventionally reared mice) and Envigo 2020SX (germ-free mice). (B) Succinate levels in the plasma from portal and tail vein of wildtype 8-week male mice fed on either Lab Diet 5053 and Envigo 2020SX for a week. Absolute quantification of butyrate (C) and succinate (D) in plasma from the portal vein versus inferior vena cava of 12-week-old germ-free male mice versus their conventionally reared mice. Relative quantification of portal TCA cycle intermediates levels in the germ-free and conventionally reared mice (E). Colony formation on the blood agar from fecal content harvested from 8-weeks old, male mice after treated with either water or antibiotic cocktails for 5 days (F). Absolute levels of portal versus tail succinate levels (G) and relative levels of portal TCA cycle intermediates levels (H) in the water versus antibiotic cocktails treated mice. Butyrate levels were measured by LC-MS/MS using D7-butyrate as internal standard. TCA cycle metabolites and absolute succinate levels were measured by GC/MS using norvaline and/or D4-succinate as internal standard (n=6 per group). Data represent means ± SEM. * p<0.05; ** p<0.01; *** p<0.001. Analysis in A and B performed via paired student t-test. Analysis in C to H were analyzed by two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni analysis for post hoc comparisons.