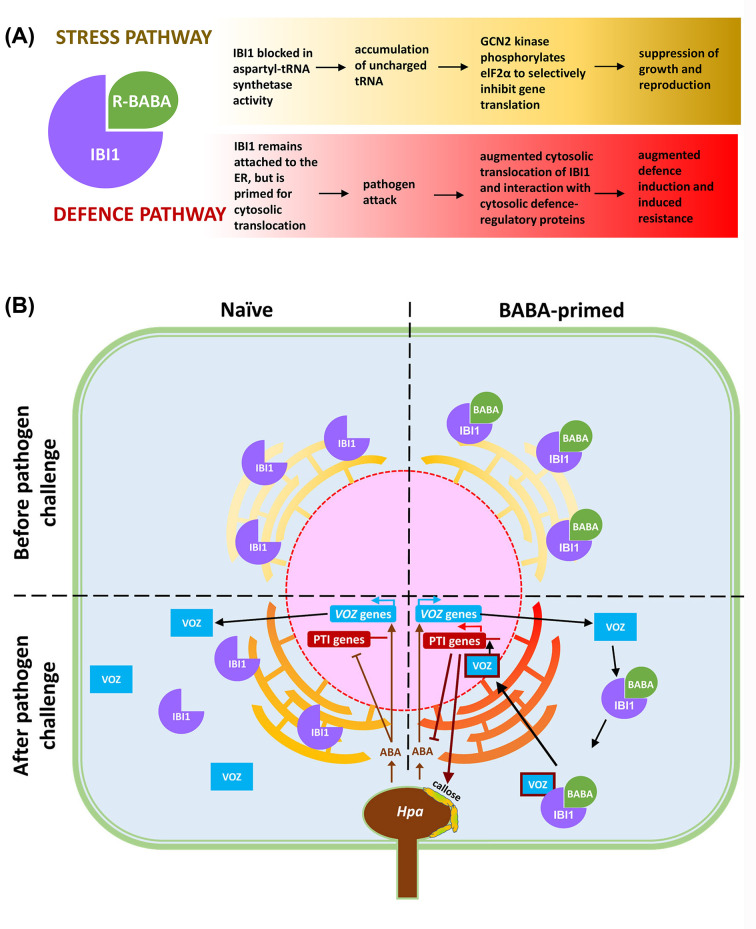

Figure 2. The IBI1 receptor of BABA controls BABA-induced stress (yellow) and BABA-induced resistance (red) via separate pathways.

(A) The R-enantiomer of BABA binds to the aspartyl tRNA synthetase IBI1 due to its structural similarity to L-aspartic acid. This disruptive binding prevents the charging of uncharged tRNA with L-aspartic acid and as a result, uncharged tRNAAsp accumulates in the cell. Upon recognition of this uncharged tRNA by the GCN2 kinase, it phosphorylates the translation initiation factor eIF2α, which selectively inhibits the translation of genes involved in growth and reproduction, causing stress. At the same time, the binding of R-BABA to IBI1 primes the protein for augmented translocation from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to the cytosol, where it interacts with defence-regulatory proteins such as the VOZ1/2 transcription factors. (B) A cellular model of BABA induced resistance against the downy mildew pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsis (Hpa; adapted from [32]). IBI1 is primarily located at the ER where it functions as an aspartyl tRNA synthetase. Binding of IBI1 to BABA after priming treatment loosens the anchorage of IBI1 to the ER, possibly through changes in ER membrane composition associated with ER stress. When attacked by Hpa, the cell accumulates abscisic acid (ABA) to suppress SA-dependent PTI. This virulence response simultaneously induces ABA-responsive VOZ1 and VOZ2 gene induction, resulting in an increased pool of VOZ1/2 transcription factors (TFs) in the cytosol. Simultaneously, the Hpa-induced translocation of IBI1 to the cytosol increases the chance for interaction between IBI1 and VOZ1/2 TFs, which activates VOZ1/2-dependent defence gene expression in the nucleus. Since IBI1 is primed to translocate to the cytosol, the interaction between IBI1 and VOZ1/2 occurs faster and stronger in BABA-treated plants after Hpa infection, resulting in augmented defence induction.