Highlights

-

•

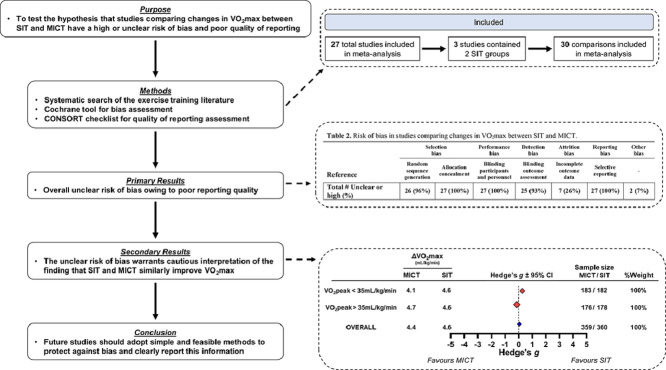

Our systematic review was the first to evaluate the risk of bias and quality of reporting in studies comparing maximal oxygen uptake responses to sprint interval training vs. moderate-intensity continuous training.

-

•

We found an overall unclear risk of bias owing to poor reporting quality in the 27 included studies. For example, only 2 studies (7%) adequately reported methods for random sequence generation, and no study reported information about allocation concealment.

-

•

This overall unclear risk of bias warrants cautious interpretation of our meta-analysis, which found, as have previously published meta-analyses, that sprint interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training similarly improve oxygen uptake.

Keywords: Bias, Cardiorespiratory fitness, CONSORT, Moderate-intensity continuous training, Sprint interval training

Abstract

Background

It remains unclear whether studies comparing maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) response to sprint interval training (SIT) vs. moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) are associated with a high risk of bias and poor reporting quality. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the risk of bias and quality of reporting in studies comparing changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive literature search of 4 major databases: AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, and MEDLINE. Studies were excluded if participants were not healthy adult humans or if training protocols were unsupervised, lasted less than 2 weeks, or utilized mixed exercise modalities. We used the Cochrane Collaboration tool and the CONSORT checklist for non-pharmacological trials to evaluate the risk of bias and reporting quality, respectively.

Results

Twenty-eight studies with 30 comparisons (3 studies included 2 SIT groups) were included in our meta-analysis (n = 360 SIT participants: body mass index (BMI) = 25.9 ± 3.7 kg/m2, baseline VO2max = 37.9 ± 8.0 mL/kg/min; n = 359 MICT participants: BMI = 25.5 ± 3.8 kg/m2, baseline VO2max = 38.3 ± 8.0 mL/kg/min; all mean ± SD). All studies had an unclear risk of bias and poor reporting quality.

Conclusion

Although we observed a lack of superiority between SIT and MICT for improving VO2max (weighted Hedge's g = −0.004, 95% confidence interval (95%CI): −0.08 to 0.07), the overall unclear risk of bias calls the validity of this conclusion into question. Future studies using robust study designs are needed to interrogate the possibility that SIT and MICT result in similar changes in VO2max.

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

There is a growing awareness of a “reproducibility crisis” in preclinical and clinical research1,2 that has widespread societal and financial ramifications.1,3 Many research groups1,4,5 attribute poor reproducibility to shortcomings in key aspects of study design (e.g., randomization, blinding, and outcome reporting), as inadequacies in these methodological areas compromise internal validity and produce biased results.6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Importantly, quality of reporting is intimately linked with bias: clinical trials that do not report information on bias-mitigating methodologies (e.g., allocation concealment) produce inflated effect sizes compared with trials with adequate reporting.6 Therefore, interpreting the internal validity of original research requires the assessment of both methodological rigor and quality of reporting.13,14

Systematic reviews provide an opportunity to evaluate the overall methodological rigor and quality of reporting in studies investigating a given research question. The Cochrane Collaboration bias assessment tool13 and the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) checklist15 are robust tools for assessing the risk of bias16 and reporting quality, respectively. Recent reports found that many systematic reviews in sports and exercise medicine research either do not evaluate the risk of bias17 or use inferior assessment tools.18 Furthermore, although several reviews have highlighted poor reporting quality in sports medicine research,19, 20, 21 we are unaware of a study that has systematically evaluated the quality of reporting in exercise medicine research.

A current hot topic in exercise medicine research is determining which mode of exercise training best improves maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max)22,23—a research question with important clinical implications considering the association between VO2max and all-cause morbidity and mortality.24 Given that a perceived lack of time is a commonly cited barrier to participating in regular, structured physical activity,25 a large body of work has developed investigating the potency of sprint interval training (SIT) — time-efficient exercise involving repeated supramaximal bouts of exercise interspersed with brief periods of rest — to improve VO2max. A recent meta-analysis demonstrated that SIT elicits similar improvements in VO2max compared with traditional endurance training (herein referred to as moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT)).26 However, neither this meta-analysis nor any recent meta-analysis examining the effects of SIT on VO2max26, 27, 28 has evaluated the risk of bias or quality of reporting within studies, which limits our confidence in the conclusion that SIT and MICT lead to similar improvements in VO2max. Consistent with the sports medicine literature,19, 20, 21 we speculate that there is a high or unclear risk of bias and poor reporting quality among studies comparing changes in VO2max following SIT and MICT.

The purpose of this systematic review was to test the hypothesis that studies comparing changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT have a high or unclear risk of bias and poor quality of reporting. A secondary purpose was to determine whether bias impacts the overall treatment effect for VO2max responses to SIT vs. MICT. Specifically, we planned to perform 2 meta-analyses: one with all studies that met our inclusion criteria, and a second only including studies judged to have a low risk of bias.18 The expectation was that this 2 meta-analysis approach would provide greater insight about our confidence in the conclusions derived from current and past meta-analyses.26 For instance, differences in overall treatment effects between these 2 meta-analyses would indicate that a high or unclear risk of bias impacted the comparison of VO2max responses following SIT and MICT.18 Systematic evaluations of methodological rigor and reporting quality are likely required for many topics in sports and exercise science, as these issues appear to be widespread.19, 20, 21, 22 We chose to evaluate studies comparing VO2max responses to SIT and MICT, as this topic is clinically relevant,24 addresses potential barriers to completing regular physical activity,25 and has a large number of studies that can be included in our analysis—as demonstrated by past systematic reviews.26, 27, 28 Although our systematic review focuses on this specific topic, our discussion provides simple and feasible recommendations applicable to all areas of exercise medicine research.

2. Methods

The present systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist;29 and a completed checklist can be found in the Supplementary material (Sheet 4). The study selection process was conducted using Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia).

2.1. Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the present systematic review if they met all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) used human adult participants between the ages of 18 and 65, (2) directly measured VO2max (or peak) using indirect calorimetry (i.e., a metabolic cart), (3) reported VO2max in relative units (mL/kg/min) or in absolute units (mL/min or L/min) with body mass (kg) so that relative VO2max could be manually calculated, (4) reported mean and standard deviation (SD) for changes in VO2max (post-training minus baseline) or VO2max at baseline and post-training, or presented data in a manner that could be extracted using WebPlotDigitizer (WebPlotDigitizer, Pacifica, CA, USA),30 (5) employed a SIT protocol that was “all-out” or supramaximal (e.g., >100% VO2max or maximal work rate) and interspersed with periods of rest or active recovery, (6) employed a MICT protocol that was continuous and submaximal (e.g., <80% VO2max or maximal work rate), and (7) conducted supervised training for a minimum of 2 weeks. Studies were excluded if they: (1) did not meet all of the inclusion criteria, (2) included non-healthy participants with a specific disease (e.g., cancer, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, etc.); note that we did not consider obesity a disease, and we included studies with obese or overweight participants that were otherwise healthy, (3) included endurance-trained athletes; however, studies in strength-trained athletes were not excluded, (4) employed mixed training protocols (e.g., MICT plus resistance training), or (5) were not in English, not an original research article, or presented previously published VO2max data.

2.2. Literature search and study selection

We conducted a comprehensive literature search in AMED, CINAHL, EMBASE, and MEDLINE on August 14th, 2019, and a second up-to-date search took place on August 18th, 2020. The searches included 3 main terms: SIT, MICT, and VO2max. A list of synonyms/related terms for each main term were combined with “OR” (see Supplementary material Sheet 2 for a full list of search terms), and a final single search combined the 3 separate lists with “AND”. Titles and abstracts were extracted from the database searches, and duplicates were automatically removed in Covidence (Covidence, Melbourne, VIA, Australia).

Study selection followed a 2-step process and was independently completed by 2 reviewers (JTB and NP). Both reviewers met in person to justify their decisions during the study selection process and to resolve any initial disagreements. Although a third reviewer (BJG) was available to settle any lasting disagreements, all initial disagreements were resolved during the in-person meetings. First, titles and abstracts were screened to identify studies that appeared to meet eligibility criteria. The 2 reviewers (JTB and NP) also screened relevant previously published systematic reviews23,26, 27, 28,31 in an attempt to identify eligible articles that were not retrieved from the initial literature search. Second, full texts were downloaded for articles that passed the title and abstract screening to determine their eligibility. Third, the 2 reviewers assigned a reason for each study excluded during the full text screening. The final analysis included studies that passed both levels of study selection.

2.3. Assessment of risk of bias and quality of reporting

We assessed the risk of bias using the 7 sources of bias and related information outlined in the Cochrane Collaboration Tool.13 The risk of each source of bias was judged as “high”, “low”, or “unclear”. In brief, studies that reported an adequate methodology for protecting against a given source of bias (e.g., blinding outcome assessors to protect against detection bias) were judged as having a “low” risk of bias. Conversely, studies that reported an inadequate methodology (e.g., randomized participants based on birth month32) were judged as having a “high” risk of bias. Studies that did not report information regarding a given methodology were judged as having an “unclear” risk of bias except in cases of reporting bias where studies were judged as having a “high” risk of bias if they did not report publicly registering their trial or if they did not report their methods in a public database/registry.

We assessed quality of reporting by completing the CONSORT checklist for non-pharmacological trials.33 Each CONSORT item was rated as “yes” (reported) or “no” (not reported), and the elaboration and explanation document14 was used to help determine the rating for each item. Two reviewers (JTB and NP) independently completed the risk of bias and quality of reporting assessments. Both reviewers met in person to justify their decisions during the assessment of risk of bias and reporting quality process to resolve any initial disagreements. Although a third reviewer (BJG) was available to settle any lasting disagreements, all initial disagreements were successfully resolved by JTB and NP.

2.4. Data extraction

Means and SDs for relative VO2max (mL/kg/min) were extracted either by recording values directly from tables/text or by using WebPlotDigitizer (Version 4.4; WebPlotDigitizer, Pacifica, CA, USA)—a data extraction approach with high inter-rater reliability and validity34—when VO2max data only appeared in figures. Mean changes in VO2max were either directly extracted from articles or calculated by subtracting the mean baseline value from the mean post-training value. We extracted relative VO2max because many studies did not report VO2max in absolute units35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44 and because increasing relative VO2max by ∼3.50 mL/kg/min confers an ∼8%–14% reduction in all-cause morbidity and mortality.45 We also extracted summaries of training protocols and additional participant characteristic data, including self-reported physical activity classification (as reported in papers), age, height, body mass, and body mass index calculated using height and body mass data. For physical activity classification, we recorded the terminology (e.g., “recreationally active”, “inactive”, etc.) that was reported in each study and any details about eligibility cut-offs for physical activity levels (when applicable). Two reviewers (JTB and NP) independently extracted data using a standardized sheet and compared results to verify that correct data were extracted.

2.5. Data synthesis

We calculated an effect size (Cohen's d) for each study to compare changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT using Eqs. (1) and (2):46,47

| Eq. (1) |

| Eq. (2) |

where delta (Δ) refers to mean changes in VO2max following SIT or MICT. SDpooled values were calculated using the SD of change scores (SDΔ) where possible (only 3 included studies reported SDΔ values48, 49, 50). For the remaining studies we calculated SDΔ according to Chapter 16.1.3.2 of the Cochrane Handbook:51 a correlation of repeated measures of r = 0.89 (calculated using VO2max data from 10 of our previously-published training studies;52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61 n = 274 participants) and the reported SD for baseline and post-training values were used. Two studies49,62 included 2 SIT groups, and separate effect sizes were calculated for each group. Because effect sizes were calculated by subtracting the mean change in VO2max following MICT from the mean change in VO2max following SIT (Eq. (1)), positive effect sizes indicated a larger increase in VO2max after SIT whereas negative effect sizes indicated a larger increase in VO2max after MICT. As Cohen's d is biased upward for sample sizes less than 20,63,64 the effect sizes for each study were corrected by converting Cohen's d values to Hedges’ g using Eq. (3):65

| Eq. (3) |

The precision of Hedges’ g effect size estimates were determined by calculating the standard error (SEg) for each Hedges’ g value using Eq. (4) such that 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs) could be constructed around each Hedges’ g estimate (95%CI = g ± (1.96 × SEg)):63,64

| Eq. (4) |

To determine whether baseline fitness impacts the comparison of VO2max responses to SIT vs. MICT, we dichotomously grouped studies using an arbitrary threshold of 35 mL/kg/min for baseline VO2max values (calculated as average between SIT and MICT groups). Effect sizes were pooled across all studies within these 2 groups and collapsed across all groups to determine an overall effect by calculating a weighted average Hedge's g and its corresponding SEg and 95%CI using Eqs. (5–7),64 where IVW refers to the inverse variance weight and SEg* refers to the standard error of the weighted average effect size:

| Eq. (5) |

| Eq. (6) |

| Eq. (7) |

We also performed a linear regression to determine whether baseline VO2max predicted the Hedges’ g values. To further investigate the impact of sex, we completed 2 additional meta-analyses using male or female participants only. Hedges’ g effect sizes were classified as small (0.2), medium (0.5), and large (0.8), as per Cohen's conventions.46 A publicly available spreadsheet66 was used to calculate an I2 statistic in order to quantify the degree of inconsistency (i.e., heterogeneity) of the overall meta-analysis.67 The degree of inconsistency was considered “low”, “moderate”, or “high” if the I2 statistic was 25%, 50%, or 75%, respectively.67 Egger's tests are commonly used to detect possible publication bias: the suppression of null or adverse findings in meta-analyses of controlled trials (e.g., equivalency or superiority of placebo).68 We did not investigate the presence of publication bias because we compared 2 experimental conditions (MICT vs. SIT) rather than comparing the efficacy of experimental conditions against a control. Additionally, we believe that heterogeneity in MICT/SIT intensities, frequencies, and durations69,70 confounds the ability to interpret Egger's test results as evidence of publication bias.

2.6. Sensitivity analysis: Does bias impact our meta-analysis?

As recommended by Büttner and colleagues,18 we planned to perform a sensitivity analysis to determine whether bias impacted our meta-analysis. In brief, a second meta-analysis including only studies identified as having a low risk of bias would be compared to the primary meta-analysis. A difference in the overall estimated effects between these 2 meta-analyses could suggest that biased results impacted the primary meta-analysis. However, as described below, this sensitivity analysis could not be performed because every study included in our meta-analysis was judged to have an unclear risk of bias. We therefore provide an informative discussion on each source of bias included in the Cochrane Collaboration tool and outline recommendations for future work instead.

3. Results

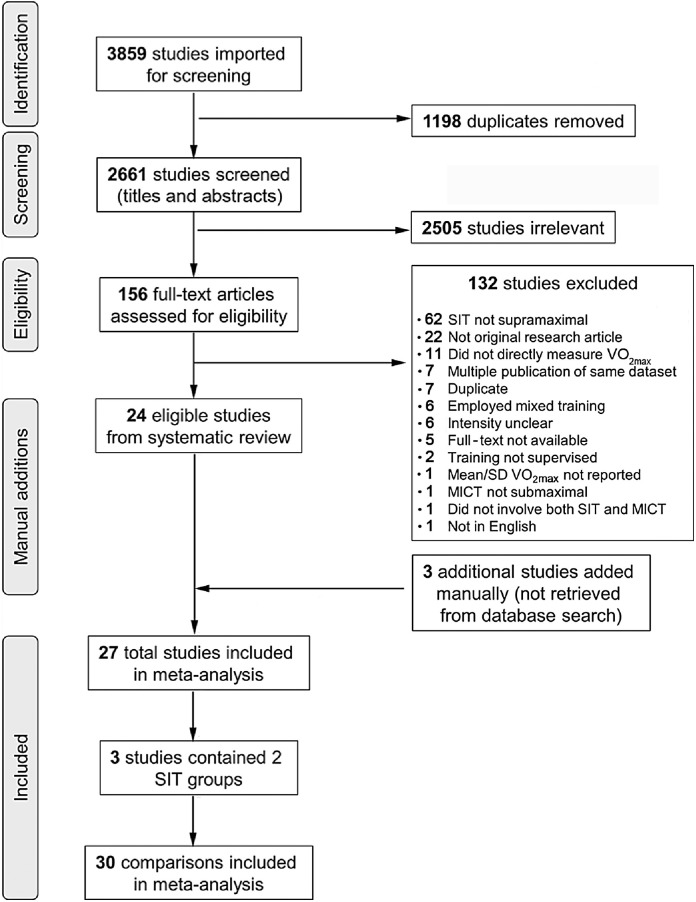

3.1. Study selection

Fig. 1 presents a flow diagram of the study selection process. The literature search retrieved 3859 articles, and Covidence removed 1198 duplicates. Of the 2661 articles that entered title and abstract screening, 2505 of these articles were deemed irrelevant and so were subsequently excluded. Full texts were then downloaded for 156 articles; 132 articles were excluded as they did not meet eligibility criteria. Included were 24 articles from the literature search and 3 additional articles35,71,72 identified from previously published systematic reviews. Therefore, 27 articles were part of the final analysis. Participant characteristics and physical activity classifications are presented in Table 1. Several studies did not report information about physical activity eligibility cut-offs, and no study objectively measured physical activity levels (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the study selection process and number of comparisons included in the meta-analysis. MICT = moderate-intensity continuous training; SIT = sprint interval training; VO2max = maximal oxygen uptake.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies comparing changes in VO2max following SIT and MICT included in the meta-analysis.

| Reference | Sample characteristics; physical activity classificationa | Age (year) |

n |

BMI (kg/m2) |

Baseline VO2max (mL/kg/min) |

SIT protocol | MICT protocol | Mode | Training frequency (session/week) |

Length of intervention (week) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIT (female) | MICT (female) | SIT | MICT | SIT | MICT | SIT | MICT | |||||||

| Bailey et al. (2009)97 | Healthy; recreationally activeb | 21 | 8 (3) | 8 (3) | 25.0 | 22.9 | 42.0 | 43.0 | 4‒7 × 30 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 4 min recovery periods |

15‒25 min at 90% VTc | C | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Bonafiglia et al. (2016)52 | Healthy; recreationally active (<3 h PA/week) | 20 | 21 (12) | 21 (12) | 23.8 | 23.7 | 41.7 | 42.2 | 8 × 20 s bouts at 170% WRpeak 20 s recovery periods |

30 min at 65% WRpeak | C | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Burgomaster et al. (2008)116 | Healthy; active (≤2 sessions PA/week) | 24 | 10 (5) | 10 (5) | 23.6 | 24.5 | 41.0 | 41.0 | 4‒6 × 30 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 4.5 min recovery periods |

40‒60 min at 65% VO2peak | C | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Cocks et al. (2013)35 | Healthy; sedentary (<1 h structured PA/week) | 22 | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | 24.8 | 22.7 | 41.9 | 41.7 | 4‒6 × 30 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 2 min recovery periods |

40‒60 min at 65% VO2peak | C | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Cocks et al. (2016)36 | Healthy and obese; sedentary (<1 h structured PA/week) | 25 | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | 35.9 | 33.4 | 33.9 | 35.1 | 4‒7 × 30 s at ∼200% WRpeak 4.5 min recovery periods |

40‒60 min at 65% VO2peak | C | 3 | 5 | 6 |

| Foster et al. (2015)37 | Healthy; relatively sedentary (<2 sessions PA/week) | NR | 21 (NR) | 19 (NR) | NR | NR | 34.0 | 33.6 | 8 × 20 s at 170% VO2max 10 s recovery periods |

20 min at 90% VT | C | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| Gillen et al. (2016)79 | Healthy; sedentary (<600 MET/week) | 27 | 9 (0) | 10 (0) | 27.1 | 26.8 | 31.9d | 33.9d | 3 × 20 s “all-out” bouts against 5% BM 2 min recovery periods |

45 min at 70% HRmax | C | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Higgins et al. (2016)80 | Healthy and overweight; active (≥2 × 30 min sessions PA/week) | 20 | 23 (23) | 29 (29) | NR | NR | 29.1 | 26.9 | 5‒7 × 30 s “all-out” bouts 4 min recovery periods |

20‒30 min at 60%‒70% HRRc | C | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Keating et al. (2014)38 | Healthy and overweight; inactive (<3 day PA/week) | 43 | 13 (11) | 13 (10) | 28.2 | 28.5 | 25.3 | 24.0 | 4‒6 × 30–60 s at 120% VO2 peak 2‒3 min recovery periods |

30‒45 min at 50%‒65% VO2peak | C | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Kiviniemi et al. (2014)76 | Healthy; sedentary (no PA level assessed; VO2peak < 40 mL/kg/min) | 48 | 13 (0) | 13 (0) | 25.5 | 26.1 | 34.7 | 33.9 | 4‒6 × 30 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 4 min recovery periods |

40‒60 min at 60% WRpeak | C | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| Kong et al. (2016)39 | Healthy and obese; sedentary (<60 min PA/week) | 21 | 13 (13) | 13 (13) | 25.8 | 25.5 | 32.0 | 32.0 | 60 × 8 s “all-out” bouts 12 s recovery periods |

40 min at 60%‒80% VO2peak | C | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Macpherson et al. (2011)40 | Healthy; recreationally activeb | 24 | 10 (4) | 10 (4) | 25.2 | 24.2 | 46.8 | 44.0 | 4‒6 × 30 s “all-out” bouts 4 min recovery periods |

30‒60 min at 65% VO2max | R | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Martins et al. (2016)49 | Healthy and obese; sedentary (<1 brisk PA/week or <3 × 20 min light PA/week) | 33 | 13 (NR) | 13 (NR) | 33.2 | 33.3 | 31.1 | 31.1 | SIT: 250 kcals of 8 s “all-out” bouts 12 s recovery periods |

32 min at 70% HRmaxc | C | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| 34 | 13 (NR) | 32.4 | 29.6 | 1/2 SIT: 125 kcals of 8 s “all-out” bouts 12 s recovery periods |

C | 3 | ||||||||

| Matsuo et al. (2014)50 | Healthy; sedentary (no regular PA) | 26 | 14 (0) | 14 (0) | 21.3 | 21.2 | 43.9 | 42.0 | 7 × 30 s at 120% VO2max 15 s recovery periods |

40 min at 60%‒65% VO2max | C | 5 | 5 | 8 |

| Mazurek et al. (2014)98 | Healthy; untrainedb | NR | 24 (24) | 22 (22) | 21.5 | 23.0 | 36.2 | 36.6 | 12 × 10 s “all-out” bouts 1 min recovery periods |

32 min at 65%‒75% HRmax | C | 3 | 3 | 8 |

| McGarr et al. (2014)41 | Healthy; recreationally activeb | 24 | 8 (2) | 8 (3) | NR | NR | 47.2 | 47.9 | 4‒5 × 30 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 4.5 min recovery periods |

60‒90 min at 65% VO2max | C | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| McKay et al. (2009)77 | Healthy; recreationally activeb | 25 | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | NR | NR | 46.0 | 43.0 | 8‒12 × 1 min bouts at 120% VO2max 1 min recovery periods |

90‒120 min at 65% VO2max | C | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3 |

| Nalcakan (2014)78 | Healthy; recreationally activeb | 22 | 8 (0) | 7 (0) | 25.5 | 24.5 | 40.2 | 40.5 | 4‒6 × 30 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 4 min recovery periods |

30‒50 min at 60% VO2max | C | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Schaun et al. (2018)42 | Healthy; no information provided | 24 | 15 (0) | 14 (0) | 23.7 | 24.7 | 47.3d | 47.3d | 8 × 20 s at 130% vVO2max 10 s recovery periods |

30 min at 90%‒95% HR at VT2 | R | 3 | 3 | 16 |

| Scribbans et al. (2014)59 | Healthy; recreationally active (<3 h PA/week) | 21 | 10 (0) | 9 (0) | 23.2 | 22.8 | 48.3 | 47.6 | 8 × 20 s bouts at 170% VO2peak 10 s recovery periods |

30 min at 65% VO2peak | C | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Skleryk et al. (2013)71 | Healthy and overweight or obese; sedentaryb | 39 | 8 (0) | 8 (0) | 32.2 | 35.2 | 29.7 | 26.3 | 8‒12 × 10 s “all-out” bouts against 5% BM 80 s recovery periods |

30 min at 65% VO2peak | C | 3 | 5 | 2 |

| Sun et al. (2019)48 | Healthy and overweight; inactive | 21 | 14 (14) | 14 (14) | 26.0 | 26.5 | 30.8 | 31.1 | 80 × 6 s “all-out” bouts 9 s recovery periods |

52‒63 min at 60% VO2max | C | 3 | 3 | 12 |

| Tabata et al. (1996)43 | Healthy; physically activeb | 23 | 7 (0) | 7 (0) | 23.2 | 24.0 | 48.2 | 52.9 | 8 × 20 s bouts at 170% VO2max 20 s recovery periods |

60 min at 60%‒70% VO2max | C | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Tanisho and Hirakawa (2009)44 | Healthy; college lacrosse playersb | 19 | 6 (0) | 6 (0) | 21.2 | 21.1 | 50.8 | 52.2 | 10 × 10 s at AnPmax 20 s recovery periods |

15 min at 70%‒75% HRmax then 1 min step test to volitional fatigue | C | 3 | 3 | 15 |

| Trapp et al. (2008)72 | Healthy; inactive b | 22 | 11 (11) | 8 (8) | 24.4 | 22.4 | 28.8 | 30.9 | 15‒60 × 8 s “all-out” bouts against ≥0.5 kg 12 s recovery periods |

10‒40 min at 60% VO2peakc | C | 3 | 3 | 15 |

| Zelt et al. (2014)62 | Healthy; recreationally active (<3 h PA/week) | 23 | 11 (0) | 13 (0) | 24.7 | 25.2 | 47.9d | 44.9d | SIT: 4‒6 × 30 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 4.5 min recovery periods |

60‒75 min at 65% VO2peak | C | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 12 (0) | 25.9 | 43.5d | 1/2 SIT: 4‒6 × 15 s “all-out” bouts against 7.5% BM 4.75 min recovery periods |

C | 3 | |||||||||

| Zhang et al. (2021)75 | Healthy and obese; activeb | 21 | 11 (11) | 11 (11) | 25.6 | 25.1 | 26.7 | 28.9 | All-out: 40 × 6 s “all-out” bouts 9 s recovery periods |

60% VO2peak until 200 KJc | C | 3.7 | 3.7 | 12 |

| 12 (12) | 26.1 | 26.4 | SIT120: 1 min at 120% VO2peak until 200 KJ 90 s recovery periods |

C | 3.7 | |||||||||

| Mean ± SD | — | 25 ± 7 | 12 ± 5 | 12 ± 5 | 25.9 ± 3.7 | 25.5 ± 3.8 | 37.9 ± 8.0 | 38.3 ± 8.0 | — | — | — | 3.3 ± 1 | 3.6 ± 1 | 8 ± 4 |

Abbreviations: AnPmax = maximal anaerobic power; BM = body mass; BMI = body mass index; C = cycling; HR = heart rate; HRmax = maximal heart rate; HRR = heart rate reserve; KJ = kilojoules; MET = metabolic equivalents; MICT = moderate-intensity continuous training; NR = not reported; PA = physical activity; R = running; SIT = sprint interval training; VO2max = maximal oxygen uptake; VO2peak = peak oxygen uptake; vVO2max = running velocity at maximal oxygen uptake; VT = ventilatory threshold; VT2 = second ventilatory threshold; WRpeak = peak work rate.

Physical activity levels were determined via self-reporting.

No information reported about eligibility cut-offs for physical activity levels.

Work-matched to SIT protocol.

Data obtained via WebPlotdigitizer.

3.2. Risk of bias assessment

Table 2 presents the risk of bias in the 27 included studies. In general, we observed an unclear risk of bias among studies comparing changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT. All 27 studies did not report methods related to adequate allocation concealment, participant blinding, or a priori identification of a primary outcome(s), and therefore had an unclear risk of selection and performance bias and a high risk of outcome reporting bias. (Note that the inability to blind participants is an inherent limitation associated with exercise training studies.73) Two studies had a high risk of “other bias” as 1 study38 imputed group means for missing data — an approach that risks reducing variability and artificially increasing the probability of detecting significance74— and the other43 did not randomize group allocation. Overall, every study included in our meta-analysis was judged to have an unclear risk of bias, and we therefore could not complete a sensitivity analysis to determine whether bias impacted our overall treatment effect.

Table 2.

Risk of bias in studies comparing changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT.

| Selection bias |

Performance bias |

Detection bias |

Attrition bias |

Reporting bias |

Other bias | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding participants and personnel | Blinding outcome assessment | Incomplete outcome data | Selective reporting | |

| Bailey et al. (2009)97 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low |

| Bonafiglia et al. (2016)52 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Burgomaster et al. (2008)116 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Cocks et al. (2013)35 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Cocks et al. (2016)36 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Foster et al. (2015)37 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Gillen et al. (2016)79 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Higgins et al. (2016)80 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Keating et al. (2014)38 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Uncleara | Low | High | Highb |

| Kiviniemi et al. (2014)76 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Kong et al. (2016)39 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Macpherson et al. (2011)40 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Martins et al. (2016)49 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclearc | High | Low |

| Matsuo et al. (2014)50 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Mazurek et al. (2014)98 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low |

| McGarr et al. (2014)41 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| McKay et al. (2009)77 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low |

| Nalcakan (2014)78 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclearc | High | Low |

| Schaun et al. (2018)42 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Scribbans et al. (2014)59 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Skleryk et al. (2013)71 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Sun et al. (2019)48 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Tabata et al. (1996)43 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Highd |

| Tanisho and Hirakawa (2009)44 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Trapp et al. (2008)72 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Zelt et al. (2014)62 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Low | High | Low |

| Zhang et al. (2021)75 | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear | High | Low |

| Total (unclear or high (%)) | 26 (96%) | 27 (100%) | 27 (100%) | 25 (93%) | 7 (26%) | 27 (100%) | 2 (7%) |

a Unclear which outcome(s) were assessed in a blinded fashion.

b Group means were input for missing individual data.

c Dropout rate >20%.

d No randomization.

Abbreviations: MICT = moderate-intensity continuous training; SIT = sprint interval training; VO2max = maximal oxygen uptake.

3.3. Quality of reporting assessment

Table 3 contains the evaluation for select CONSORT items related to key aspects of study design (e.g., randomization procedures, blinding, outcome reporting, and sample size calculations), and the Supplementary material (Sheet 3) presents the evaluation, including all CONSORT items. The high number of “✗” symbols (indicating no reporting or inadequate reporting) in Table 3 highlights an overall poor quality of reporting: 209 “✗” symbols vs. 51 “✓” symbols. Additionally, no study adequately reported CONSORT Items 9 and 10, which relate to allocation concealment and randomization implementation procedures, respectively.

Table 3.

Checklist of select CONSORT items to assess quality of reporting in studies comparing changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT.

| CONSORT Item # (see footnote for item topics) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | 4A | 5B | 6A | 7A | 8A | 9 | 10 | 11A | 13A | 17A |

| Bailey et al. (2009)97 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Bonafiglia et al. (2016)52 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Burgomaster et al. (2008)116 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Cocks et al. (2013)35 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Cocks et al. (2016)36 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Foster et al. (2015)37 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Gillen et al. (2016)79 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Higgins et al. (2016)80 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Keating et al. (2014)38 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kiviniemi et al. (2014)76 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Kong et al. (2016)39 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Macpherson et al. (2011)40 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Martins et al. (2016)49 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Matsuo et al. (2014)50 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Mazurek et al. (2014)98 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| McGarr et al. (2014)41 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| McKay et al. (2009)77 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Nalcakan (2014)78 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Schaun et al. (2018)42 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Scribbans et al. (2014)59 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Skleryk et al. (2013)71 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Sun et al. (2019)48 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Tabata et al. (1996)43 | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Tanisho and Hirakawa (2009)44 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Trapp et al. (2008)72 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Zelt et al. (2014)62 | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Zhang et al. (2021)75 | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Total ✗ (%) | 16 (59%) | 22 (81%) | 22 (81%) | 20 (74%) | 25 (93%) | 27 (100%) | 27 (100%) | 24 (89%) | 7 (26%) | 26 (96%) |

Notes: CONSORT item topics:33 4A = eligibility criteria for participants; 5B = details of whether and how interventions were standardized; 6A = completely defined pre-specified primary outcome; 7A = how sample size was determined; 8A = method used for random sequence generation; 9 = allocation concealment mechanism; 10 = implementation of randomization procedures; 11A = blinding; 13A = participant flow; 17A = results for primary outcome including precision.

✗ Judged to be not or inadequately reported; ✓ Judged to be adequately reported.

Abbreviations: MICT = moderate-intensity continuous training; SIT = sprint interval training; VO2max = maximal oxygen uptake.

3.4. Data synthesis

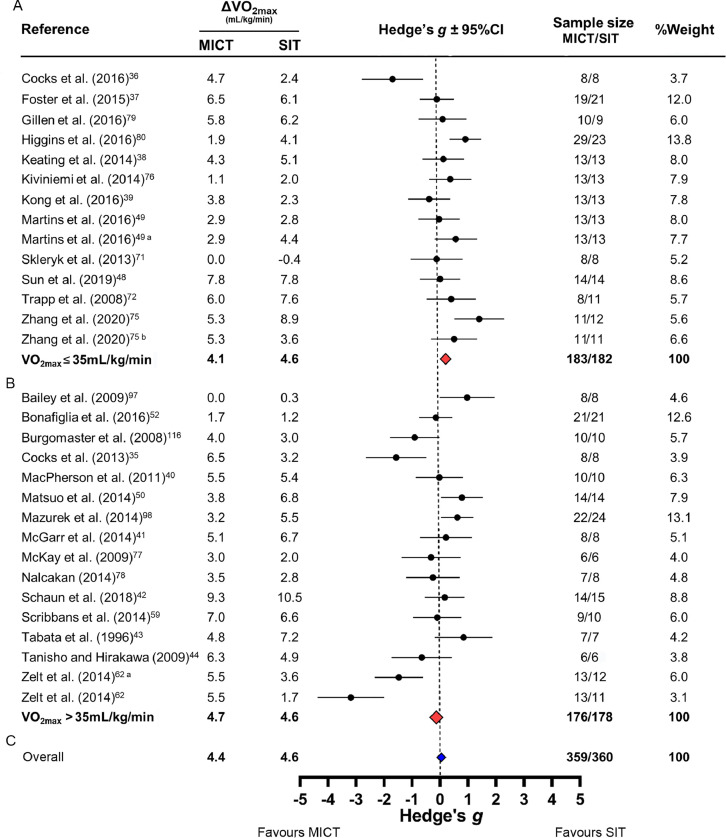

Three49,62,75 of the 27 studies contained 2 SIT interventions that were both compared to MICT. Therefore, 30 comparisons were included in the meta-analysis with a total sample size of 360 SIT and 359 MICT participants. Fig. 2 presents changes in VO2max, effect sizes (Hedge's g), sample sizes, and percent contribution toward weighted effect size (%weight) for each comparison. Fig. 2 is sorted by mean baseline VO2max: less (Fig. 2A) or greater (Fig. 2B) than 35 mL/kg/min (see Table 1 for mean baseline values). In both baseline fitness groups, the vast majority of 95%CIs crossed zero (11/14 in Fig. 2A; 10/16 in Fig. 2B). Baseline VO2max did not appear to influence Hedges’ g values, as the 95%CI for both weighted effect sizes crossed zero (Fig. 2), and the linear regression was not significant (r2 = 0.07, r = –0.28, p = 0.12). Fig. 2 also presents the overall weighted effect size when we pooled across all studies regardless of baseline VO2max (blue diamond). The mean overall changes in VO2max were +4.6 mL/kg/min following SIT and +4.4 mL/kg/min following MICT, and the weighted average Hedge's g was 0.06 (SE = 0.08) with a 95%CI crossing zero (–0.08 to 0.07). Collectively, these results highlight a lack of superiority between SIT and MICT for improving VO2max regardless of baseline VO2max. Additionally, the I2 statistic (72%) indicated substantial inconsistency of effect sizes across comparisons.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of the meta-analysis comparing changes in relative maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) following sprint interval training (SIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) separated by baseline VO2max: (A) <35 mL/kg/min; (B) >35 mL/kg/min; (C) the overall effect with all studies included. Because effect sizes were calculated as (SIT minus MICT) divided by pooled standard deviation, negative values reflect larger changes in VO2max following MICT whereas positive values reflect larger changes following SIT. The red diamonds represent the overall weighted effect size (Hedge's g) for each baseline fitness group, and the blue diamond represents the overall weighted effect size including all studies. The horizontal points of the diamonds represent the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). The meta-analysis revealed a low–moderate degree of inconsistency (I2 = 38%). Overall changes in VO2max presented as averages, and overall number of participants presented as total sums. Comparison of 1/2 SIT (a) or “all-out” SIT (b) vs. MICT (see Table 1 for details).

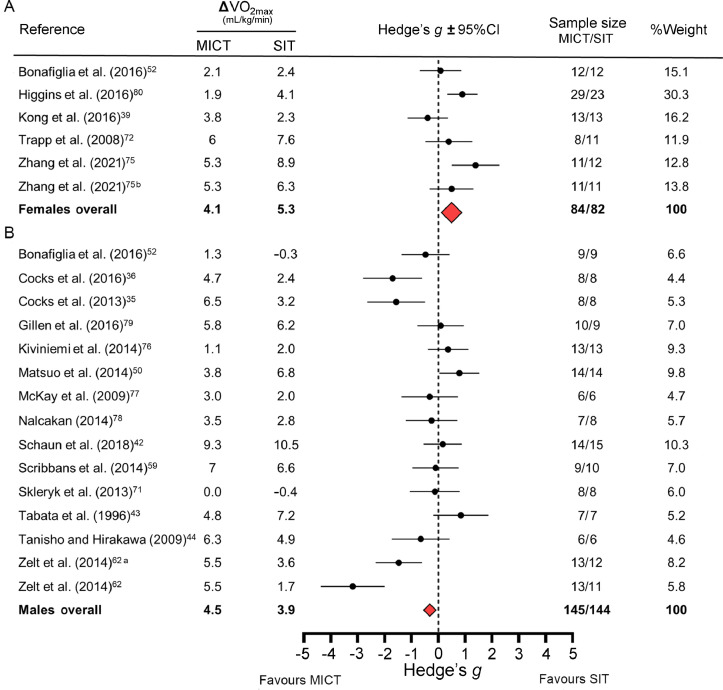

Fig. 3 presents forest plots separated by sex, which includes a smaller subset of studies as few included only males35,36,42, 43, 44,50,59,62,71,76, 77, 78, 79 or only females,39,72,75,80 and only one study reported sex-specific VO2max data.52 The 95%CIs for the overall Hedge's g values did not cross zero for either sex (Fig. 3). These meta-analyses reveal a possible sex-specific response: females appear to respond more favorably to SIT while males respond more favorably to MICT. However, this interpretation should be made with caution as these meta-analyses were completed with a smaller subset of studies and because both weighted effect sizes were small. Overall Hedge's g values were 0.55 (favoring SIT) for females and –0.32 (favoring MICT) for males.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot on subset of studies that reported sex-specific data or included only female or male participants. Forest plot depicts meta-analysis comparing changes in relative maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max) following sprint interval training (SIT) and moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) separated by sex: (A) females and (B) males. Because effect sizes were calculated as (SIT minus MICT) divided by pooled standard deviation, negative values reflect larger changes in VO2max following MICT whereas positive values reflect larger changes following SIT. The red diamonds represent the overall weighted effect size (Hedge's g) for each baseline fitness group, and the horizontal points of the diamonds represent the upper and lower bounds of the 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). Overall changes in VO2max presented as averages, and overall number of participants presented as total sums. Comparison of 1/2 SIT (a) or “all-out” SIT (b) vs. MICT (see Table 1 for details).

4. Discussion

The novel finding of our systematic review was that studies comparing changes in relative VO2max between SIT and MICT—including several of our own52,59,62— had an overall unclear risk of bias and poor quality of reporting. Our meta-analysis revealed that SIT and MICT similarly improve VO2max (Hedge's g = 0.05, 95%CI: –0.10 to 0.20), and this finding is consistent with the previous meta-analysis by Gist et al.26 (Cohen's d = 0.04, 95%CI: –0.17 to 0.24). However, the overall unclear risk of bias warrants cautious interpretation of these meta-analyses. Specifically, if the presence of bias produced inaccurate effect sizes for each study included in these meta-analyses, then the overall effect size and associated interpretation may also be inaccurate. It is also likely that the substantial inconsistency in these meta-analyses (Fig. 2 and the meta-analysis by Gist and colleagues26) is attributable to differences in the frequency, intensity, and duration of MICT and SIT protocols across studies. We refer the reader to recent reviews that discuss this issue in greater detail.69,70 Our uncertainty in knowing whether or not bias-protecting methodologies were implemented emphasizes the importance of transparent and full reporting as outlined in the CONSORT guidelines.15 Although many journals endorse the CONSORT guidelines in the attempt to improve quality of reporting,81 the success of this approach is incumbent on editors, peer-reviewers, and authors to ensure that submitted manuscripts adhere to these guidelines. Collectively, our findings highlight several major concerns with studies comparing VO2max responses between SIT and MICT and support the need for rigorous risk of bias and reporting quality assessments in future systematic reviews of exercise medicine research.16,18

The poor quality of reporting (Table 3) meant we had to assign an “unclear” risk of bias for most studies (Table 2) as it is possible that studies protected against sources of bias but failed to report doing so. Devereaux et al.82 contacted authors of large clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and found that many authors claimed to have performed bias-mitigating methodologies despite not reporting this information in their publications. Although this finding supports the idea that a lack of reporting does not necessarily reflect a lack of methodological rigor in large clinical RCTs, we are unaware of similar evidence in applied exercise science research. In contrast, strong meta-epidemiological evidence demonstrates that studies failing to report measures taken to mitigate bias (e.g., allocation concealment) produce inflated/biased effect sizes.6 This meta-epidemiological evidence supports a “guilty until proven innocent” approach whereby one should not assume a study protected against biased results unless the bias-mitigating methodologies were explicitly reported.83 However, additional empirical data supporting this approach is lacking as the majority of meta-epidemiological analyses do not separate studies with poor reporting from those that report performing an inadequate methodology.7, 8, 9,84 To determine whether a lack of reporting per se is associated with biased results, future work should compare effect sizes from studies with poor reporting vs studies that report performing an inadequate methodology.

Unfortunately, we could not perform a sensitivity analysis to determine the influence of bias on our meta-analysis,18 as no study was judged to have a low risk of bias. If we could have performed this sensitivity analysis, a different result (e.g., the overall 95%CI lay fully on one side of 0 indicating superiority of either MICT or SIT) might have suggested that biased results impacted our meta-analysis (Fig. 2). The impact of bias was demonstrated by Pildal et al.9 who found that approximately two-thirds of meta-analyses reporting an overall treatment effect lost this effect when only including studies that reported an adequate allocation concealment method. This finding supports the recent recommendations by Büttner and colleagues18 that, when applicable, future meta-analyses should conduct a sensitivity analysis to determine whether or not overall effects change when only including studies with a low risk of bias.

We provide a discussion below that describes each source of bias covered in the Cochrane Collaboration tool and makes recommendations to improve the overall methodological rigor of future studies comparing clinical outcomes between SIT and MICT. We also discuss sample size calculations as this aspect of study design was largely overlooked in the studies included in our meta-analysis (CONSORT Item 7A; Table 3).

4.1. Selection bias

Selection bias can occur when investigators assign participants to a given intervention group non-randomly.85 Protecting against selection bias requires generating an unpredictable random allocation sequence and concealing this sequence from all investigators involved in enrolling participants: a process referred to as “allocation concealment”.86, 87, 88 It is unclear whether or not studies included in our meta-analysis overlooked protecting against selection bias (Table 2) because most studies failed to report methodologies related to random sequence generation (CONSORT Item 8A), allocation concealment (CONSORT Item 9), and the implementation of these randomization procedures (CONSORT Item 10) (Table 3). It is imperative that future studies clearly report these procedures to allow researchers to easily assess the adequacy of these methods. Because there are many methods that fail to conceal allocation (e.g., sealed envelopes or randomizing via birth month),32,89,90 clear and transparent reporting is the only definitive way to demonstrate that a given study adequately protected against selection bias. For an example of clear reporting of adequate methods for reducing the risk of selection bias, we refer the reader to our recent study, in which we utilized a third party to generate a random allocation sequence using Microsoft Excel and conceal this sequence until group assignment.91

4.2. Performance bias

Performance bias can occur when participants and/or personnel administering the interventions are not blinded to participants’ group assignments.13 Protecting against performance bias requires blinding participants as well as personnel to participants’ group assignments.13,14 All 27 studies included in our meta-analysis had an unclear risk of performance bias (Table 2), and this finding likely reflects the difficulty of blinding participants and personnel in exercise training studies.73,92 In situations where participants and/or personnel cannot be blinded, the CONSORT statement for non-pharmacological trials33 recommends that researchers report any attempts to limit performance bias (CONSORT Item 11C). However, only 2 studies38,50 reported an attempt to reduce the possible impact of performance bias (Supplementary material, Sheet 3). Future studies comparing changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT should report attempts to reduce the risk of performance bias, such as concealing the study's hypothesis to participants and/or personnel.14,93

4.3. Detection bias

Detection bias, also known as observer or ascertainment bias,14 can occur when investigators responsible for assessing outcomes (herein referred to as “outcome assessors”) are aware of participants’ group assignments.94 Protecting against detection bias requires that outcome assessors are blinded to participants’ group assignments. The majority of studies included in our meta-analysis (25/27) had an unclear risk of detection bias (Table 2) as few studies reported whether or not outcome assessors were blinded (CONSORT Item 11A) (Table 3). Given this lack of clarity, we will highlight 2 possible methods for blinding VO2max outcomes assessors that could be reported in original manuscripts (if applicable). First, given evidence that encouragement affects obtained VO2max values,95 the individual performing the VO2max could be blinded to prevent them from providing unequal encouragement (e.g., more encouragement for SIT participants to align with assessor's belief that SIT is superior). Second, despite the objective nature of obtaining VO2max values (e.g., highest 30-s average), VO2max datafiles can be coded to prevent outcome assessors from manipulating or fabricating data. For an example of clear reporting of methods for blinding outcome assessors, we refer the reader to our recent study, in which we utilized a third party to code samples and data files .91

4.4. Attrition bias

Attrition bias can occur when participants are lost to follow-up in a non-random fashion between groups (i.e., more dropouts in one group compared to another).96 When dropout rates are high and/or systematically different between groups, protecting against attrition bias can involve adopting an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis whereby imputation methods generate data for dropouts so that all randomized participants are included in statistical analyses.14 The majority of studies included in our meta-analysis (20/27) had low rates of dropout and thus had a low risk of attrition bias (Table 2). Of the 6 studies with an unclear risk of attrition bias, 4 studies43,77,97,98 did not report the number of dropouts (CONSORT Item 13A), reasons for dropout (CONSORT Item 13B), or the number of participants analyzed (CONSORT Item 16; Supplementary material); 2 studies49,78 did not adopt an ITT analysis despite having dropout rates exceeding 20%, a rate that may introduce bias.99 Future studies should protect against attrition bias by reporting the number of dropouts and reasons for them and by considering adopting an ITT analysis if dropout rates are high.

4.5. Reporting bias

Reporting bias occurs when authors selectively report the results for certain outcomes and withhold the results for others.11 Protecting against reporting bias requires that researchers report a study's methods, including a list of primary and secondary outcomes, in a public registry or protocol publication before starting data collection.100 All 27 studies included in our meta-analysis had a high risk of reporting bias as the majority of studies (26/27) did not report their methodologies in a public registry. Although Kiviniemi et al.76 registered their protocol (CONSORT Item 23; Supplementary material), it was unclear whether or not these authors selectively reported outcomes, as a list of primary and secondary outcomes was not included in their registration file (clinicaltrials.gov: NCT01344928). Collectively, these findings highlight an overall high risk of reporting bias, which emphasizes the need for future work to report the primary outcome(s) a priori in a public registry (see Refs.101, 102, 103 for examples of public registries).

4.6. Sample size calculations

Small sample sizes risk generating a type II error (i.e., a false negative).104 An a priori sample size calculation estimates the sample size needed to statistically detect an expected effect at a pre-determined level of statistical power (i.e., probability of not making a type II error; typically 80%).105 Performing a priori sample size calculations and subsequently ensuring enrollment reaches the indicated sample size only helps reduce the risk of type II errors if calculations are completed accurately. Sample size calculations should utilize equations and assumptions that match the planned statistical analysis106,107 and should be based on either a clinically meaningful change or an expected effect size and variance derived from previous studies using similar designs, populations, and methods for outcome assessment.14 Assessing the accuracy of a given sample size calculation requires that researchers report and justify the associated statistical parameters, which include the desired statistical power/type II error risk, alpha level/type I error risk, and the expected effect size and variance.14 Failing to perform an accurate a priori sample size calculation precludes researchers’ ability to determine whether a reported non-significant result reflects a true finding or a type II error.104

The majority of studies (21/27) included in our meta-analysis either failed to report or inadequately reported whether or not they performed an a priori sample size calculation (CONSORT Item 6A) (Table 3). Thus, it is unclear whether or not these studies may have made a type II error when concluding that SIT and MICT are equally effective at improving VO2max. In theory, future studies could perform an a priori calculation to determine the sample size needed to detect a significant difference between SIT and MICT. However, because our overall effect size indicated a lack of superiority between SIT and MICT (Fig. 2), future studies could consider conducting a non-inferiority trial to determine whether SIT and MICT are equally beneficial at improving VO2max (see Refs.108,109 for information on non-inferiority trials).

4.7. Limitations

Our systematic review focused on VO2max responses to SIT and MICT, and it is therefore unclear whether our findings are generalizable to other areas of exercise medicine research. A popular topic in studies involving endurance athletes is determining the potency of supplementing habitual exercise training with SIT or high-intensity interval training.110, 111, 112, 113, 114 Although García-Pinillos et al.115 recently evaluated the methodological rigor of studies using high-intensity interval training to augment training load for endurance runners, these authors used inferior assessment tools (i.e., the PEDro Scale and Downs and Black Quality Index)18 and did not assess reporting quality. This is one of many examples of topics in exercise science research that warrant a systematic evaluation of methodological rigor and reporting quality using the Cochrane Collaboration tool and CONSORT checklist, respectively.

5. Conclusion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis found an unclear risk of bias owing to poor reporting quality in studies comparing changes in VO2max between SIT and MICT. Given these apparent methodological issues, future studies are encouraged to implement bias-reducing methodologies, as outlined in the Cochrane Collaboration tool, and to follow the reporting recommendations outlined in the CONSORT checklist for non-pharmacological trials. Furthermore, future systematic reviews in exercise medicine research should evaluate and (if possible) account for the risk of bias and reporting quality when synthesizing results in a meta-analysis. Although we focused on studies examining changes in VO2max following SIT and MICT in humans, the methodological and reporting principles highlighted in this review are applicable to all disciplines within exercise and sports medicine research.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by an operating grant from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC; grant number: 402635) to BJG. JTB was supported by a NSERC Vanier Canada Graduate Scholarship, HI was supported by NSERC PGS-D, and NP was supported by NSERC CGS-M.

Authors’ contributions

JTB and NP conducted the literature review. All authors contributed to the study conception and design and the writing of the first draft, commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript, and agree with the order of presentation of the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Shanghai University of Sport.

Supplementary materials associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.jshs.2021.03.005.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Begley CG, Ioannidis JP. Reproducibility in science: Improving the standard for basic and preclinical research. Circ Res. 2015;116:116–126. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.303819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker M, Penny D. Is there a reproducibility crisis? Nature. 2016;533:452–454. doi: 10.1038/533452a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Freedman LP, Cockburn IM, Simcoe TS. The economics of reproducibility in preclinical research. PLoS Biol. 2015;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landis SC, Amara SG, Asadullah K, et al. A call for transparent reporting to optimize the predictive value of preclinical research. Nature. 2012;490:187–191. doi: 10.1038/nature11556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramirez FD, Motazedian P, Jung RG, et al. Methodological rigor in preclinical cardiovascular studies: Targets to enhance reproducibility and promote research translation. Circ Res. 2017;120:1916–1926. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.117.310628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulz KF, Chalmers I, Hayes RJ, Altman DG. Empirical evidence of bias. Dimensions of methodological quality associated with estimates of treatment effects in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;273:408–412. doi: 10.1001/jama.273.5.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Page MJ, Higgins JP, Clayton G, Sterne JA, Hróbjartsson A, Savović J. Empirical evidence of study design biases in randomized trials: Systematic review of meta-epidemiological studies. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood L, Egger M, Gluud LL, et al. Empirical evidence of bias in treatment effect estimates in controlled trials with different interventions and outcomes: Meta-epidemiological study. BMJ. 2008;336:601–605. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39465.451748.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pildal J, Hróbjartsson A, Jørgensen KJ, Hilden J, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC. Impact of allocation concealment on conclusions drawn from meta-analyses of randomized trials. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:847–857. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nüesch E, Reichenbach S, Trelle S, et al. The importance of allocation concealment and patient blinding in osteoarthritis trials: A meta-epidemiologic study. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1633–1641. doi: 10.1002/art.24894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dwan K, Gamble C, Williamson PR, Kirkham JJ, Reporting Bias Group Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias – an updated review. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ioannidis JP. Why most published research findings are false. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.The Lancet CONSORT 2010. The Lancet. 2010;375:1136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60456-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Büttner F, Winters M, Delahunt E, et al. Identifying the “incredible”! Part 1: Assessing the risk of bias in outcomes included in systematic reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:798–800. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-100806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weir A, Rabia S, Ardern C. Trusting systematic reviews and meta-analyses: All that glitters is not gold! Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1100–1101. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Büttner F, Winters M, Delahunt E, et al. Identifying the “incredible”!Part 2: Spot the difference–a rigorous risk of bias assessment can alter the main findings of a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2020;54:801–808. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Serner A, van Eijck CH, Beumer BR, Hölmich P, Weir A, de Vos RJ. Study quality on groin injury management remains low: A systematic review on treatment of groin pain in athletes. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:813. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2014-094256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Read P, Mc Auliffe S, Wilson MG, Myer GD. Better reporting standards are needed to enhance the quality of hop testing in the setting of ACL return to sport decisions: A narrative review. Br J Sports Med. 2021;55:23–29. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon U, Knobloch K. Quality of reporting in sports injury prevention abstracts according to the CONSORT and STROBE criteria: An analysis of the World Congress of Sports Injury Prevention in 2005 and 2008. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:202–206. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.053876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Batacan RB, Jr., Duncan MJ, Dalbo VJ, Tucker PS, Fenning AS. Effects of high-intensity interval training on cardiometabolic health: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention studies. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:494–503. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sultana RN, Sabag A, Keating SE, Johnson NA. The effect of low-volume high-intensity interval training on body composition and cardiorespiratory fitness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sport Med. 2019;49:1687–1721. doi: 10.1007/s40279-019-01167-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, et al. Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: A case for fitness as a clinical vital sign: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2016;134:e653–e699. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trost SG, Owen N, Bauman AE, Sallis JF, Brown W. Correlates of adults’ participation in physical activity: Review and update. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2002;34:1996–2001. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gist NH, Fedewa MV, Dishman RK, Cureton KJ. Sprint interval training effects on aerobic capacity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2014;44:269–279. doi: 10.1007/s40279-013-0115-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sloth M, Sloth D, Overgaard K, Dalgas U. Effects of sprint interval training on VO2max and aerobic exercise performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2013;23:e341–e352. doi: 10.1111/sms.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vollaard NBJ, Metcalfe RS, Williams S. Effect of number of sprints in an SIT session on change in VO2max: A meta-analysis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49:1147–1156. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohatgi A. WebPlotDigitizer. Available at: https://automeris.io/WebPlotDigitizer. [accessed 18.11. 2018 ].

- 31.Milanović Z, Sporiš G, Weston M. Effectiveness of High-Intensity Interval Training (HIT) and continuous endurance training for VO2max improvements: A systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled trials. Sport Med. 2015;45:1469–1481. doi: 10.1007/s40279-015-0365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Altman DG. Randomisation. BMJ. 1991;302:1481–1482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boutron I, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF, Ravaud P. CONSORT NPT Group. CONSORT Statement for randomized Trials of nonpharmacologic treatments: A 2017 update and a CONSORT extension for nonpharmacologic Trial Abstracts. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:40–47. doi: 10.7326/M17-0046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drevon D, Fursa SR, Malcolm AL. Intercoder reliability and validity ofWebPlotDigitizer in extracting graphed data. Behav Modif. 2017;41:323–339. doi: 10.1177/0145445516673998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cocks M, Shaw CS, Shepherd SO, et al. Sprint interval and endurance training are equally effective in increasing muscle microvascular density and eNOS content in sedentary males. J Physiol. 2013;591:641–656. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2012.239566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cocks M, Shaw CS, Shepherd SO, et al. Sprint interval and moderate-intensity continuous training have equal benefits on aerobic capacity, insulin sensitivity, muscle capillarisation and endothelial eNOS/NAD(P)Hoxidase protein ratio in obese men. J Physiol. 2016;594:2307–2321. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.285254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster C, Farland CV, Guidotti F, et al. The effects of high intensity interval training vs. steady state training on aerobic and anaerobic capacity. J Sports Sci Med. 2015;14:747–755. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keating SE, Machan EA, O'Connor HT, et al. Continuous exercise but not high intensity interval training improves fat distribution in overweight adults. J Obes. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/834865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kong Z, Fan X, Sun S, Song L, Shi Q, Nie J. Comparison of high-intensity interval training and moderate-to-vigorous continuous training for cardiometabolic health and exercise enjoyment in obese young women: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Macpherson RE, Hazell TJ, Olver TD, Paterson DH, Lemon PW. Run sprint interval training improves aerobic performance but not maximal cardiac output. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2011;43:115–122. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e5eacd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McGarr GW, Hartley GL, Cheung SS. Neither short-term sprint nor endurance training enhances thermal response to exercise in a hot environment. J Occup Environ Hyg. 2014;11:47–53. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2013.816429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schaun GZ, Pinto SS, Silva MR, Dolinski DB, Alberton CL. Whole-body high-intensity interval training induce similar cardiorespiratory adaptations compared with traditional high-intensity interval training and moderate-intensity continuous training in healthy men. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32:2730–2742. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0000000000002594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tabata I, Nishimura K, Kouzaki M, et al. Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on aerobic capacity and VO2max. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 1996;28:1327–1330. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199610000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tanisho K, Hirakawa K. Training effects on endurance capacity in maximal intermittent exercise: Comparison between continuous and interval training. J Strength Cond Res. 2009;23:2405–2410. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181bac790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dorn J, Naughton J, Imamura D, Trevisan M. Results of a multicenter randomized clinical trial of exercise and long-term survival in myocardial infarction patients: The National Exercise and Heart Disease Project (NEHDP) Circulation. 1999;100:1764–1769. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.17.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Turner HM.I, Bernard RM. Calculating and synthesizing effect sizes. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord. 2006;33:42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun S, Zhang H, Kong Z, Shi Q, Tong TK, Nie J. Twelve weeks of low volume sprint interval training improves cardio-metabolic health outcomes in overweight females. J Sports Sci. 2019;37:1257–1264. doi: 10.1080/02640414.2018.1554615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martins C, Kazakova I, Ludviksen M, et al. High-intensity interval training and isocaloric moderate-intensity continuous training result in similar improvements in body composition and fitness in obese individuals. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab. 2016;26:197–204. doi: 10.1123/ijsnem.2015-0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Matsuo T, Saotome K, Seino S, et al. Effects of a low-volume aerobic-type interval exercise on VO2max and cardiac mass. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2014;46:42–50. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3182a38da8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. 2nd ed. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2019. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bonafiglia JT, Rotundo MP, Whittall JP, Scribbans TD, Graham RB, Gurd BJ. Inter-individual variability in the adaptive responses to endurance and sprint interval training: A randomized crossover study. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bonafiglia JT, Edgett BA, Baechler BL, et al. Acute upregulation of PGC-1α mRNA correlates with training induced increases in SDH activity in human skeletal muscle. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2017;42:656–666. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Del Giudice M, Bonafiglia JT, Islam H, Preobrazenski N, Amato A, Gurd BJ. Investigating the reproducibility of maximal oxygen uptake responses to high-intensity interval training. J Sci Med Sport. 2020;23:94–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2019.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raleigh JP, Giles MD, Scribbans TD, et al. The impact of work-matched interval training on V̇O2peak and V̇O2 kinetics: Diminishing returns with increasing intensity. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:706–713. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2015-0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Raleigh JP, Giles MD, Islam H, et al. Contribution of central and peripheral adaptations to changes in maximal oxygen uptake following 4 weeks of sprint interval training. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2018;43:1059–1068. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2017-0864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boyd JC, Simpson CA, Jung ME, Gurd BJ. Reducing the intensity and volume of interval training diminishes cardiovascular adaptation but not mitochondrial biogenesis in overweight/obese men. PLoS One. 2013;8:e68091. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Scribbans TD, Ma JK, Edgett BA, et al. Resveratrol supplementation does not augment performance adaptations or fibre-type-specific responses to high-intensity interval training in humans. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2014;39:1305–1313. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2014-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scribbans TD, Edgett BA, Vorobej K, et al. Fibre-specific responses to endurance and low volume high intensity interval training: Striking similarities in acute and chronic adaptation. PLoS One. 2014;9:e98119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Islam H, Siemens TL, Matusiak JBL, et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and muscular endurance responses immediately and two-months after a whole-body Tabata or vigorous-intensity continuous training intervention. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2020;45:650–658. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2019-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Preobrazenski N, Bonafiglia JT, Nelms MW, et al. Does blood lactate predict the chronic adaptive response to training: A comparison of traditional and talk test prescription methods. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2019;44:179–186. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2018-0343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zelt JG, Hankinson PB, Foster WS, et al. Reducing the volume of sprint interval training does not diminish maximal and submaximal performance gains in healthy men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2014;114:2427–2436. doi: 10.1007/s00421-014-2960-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: A practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2007;82:591–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2007.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Turner HM, III, Bernard RM. Calculating and synthesizing effect sizes. Contemp Issues Commun Sci Disord. 2006;33:42–55. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hedges LV, Olkin I. Academic Press; Orlando, FL: 1985. Statistical methods for meta-analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Neyeloff JL, Fuchs SC, Moreira LB. Meta-analyses and Forest plots using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet: Step-by-step guide focusing on descriptive data analysis. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:52. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Viana RB, de Lira CAB, Naves JPA, et al. Can we draw general conclusions from interval training studies? Sport Med. 2018;48:2001–2009. doi: 10.1007/s40279-018-0925-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Andreato LV. High-intensity interval training: Methodological considerations for interpreting results and conducting research. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2020;31:812–817. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2020.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Skleryk JR, Karagounis LG, Hawley JA, Sharman MJ, Laursen PB, Watson G. Two weeks of reduced-volume sprint interval or traditional exercise training does not improve metabolic functioning in sedentary obese men. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:1146–1153. doi: 10.1111/dom.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Trapp EG, Chisholm DJ, Freund J, Boutcher SH. The effects of high-intensity intermittent exercise training on fat loss and fasting insulin levels of young women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:684–691. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hecksteden A, Faude O, Meyer T, Donath L. How to construct, conduct and analyze an exercise training study? Front Physiol. 2018;9:1007. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Streiner DL. Missing data and the trouble with LOCF. Evid Based Ment Health. 2008;11:3–5. doi: 10.1136/ebmh.11.1.3-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang H, Tong TK, Kong Z, Shi Q, Liu Y, Nie J. Exercise training-induced visceral fat loss in obese women: The role of training intensity and modality. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2021;31:30–43. doi: 10.1111/sms.13803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kiviniemi AM, Tulppo MP, Eskelinen JJ, et al. Cardiac autonomic function and high-intensity interval training in middle-age men. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2014;46:1960–1967. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.McKay BR, Paterson DH, Kowalchuk JM. Effect of short-term high-intensity interval training vs. continuous training on O2 uptake kinetics, muscle deoxygenation, and exercise performance. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;107:128–138. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90828.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Nalcakan GR. The effects of sprint interval vs. continuous endurance training on physiological and metabolic adaptations in young healthy adults. J Hum Kinet. 2014;44:97–109. doi: 10.2478/hukin-2014-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gillen JB, Martin BJ, MacInnis MJ, Skelly LE, Tarnopolsky MA, Gibala MJ. Twelve weeks of sprint interval training improves indices of cardiometabolic health similar to traditional endurance training despite a five-fold lower exercise volume and time commitment. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Higgins S, Fedewa MV, Hathaway ED, Schmidt MD, Evans EM. Sprint interval and moderate-intensity cycling training differentially affect adiposity and aerobic capacity in overweight young-adult women. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2016;41:1177–1183. doi: 10.1139/apnm-2016-0240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shamseer L, Hopewell S, Altman DG, Moher D, Schulz KF. Update on the endorsement of CONSORT by high impact factor journals: A survey of journal “Instructions to Authors” in 2014. Trials. 2016;17:301. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1408-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Devereaux PJ, Choi PT, El-Dika S, et al. An observational study found that authors of randomized controlled trials frequently use concealment of randomization and blinding, despite the failure to report these methods. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:1232–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jüni P, Altman DG, Egger M. Systematic reviews in health care: Assessing the quality of controlled clinical trials. BMJ. 2001;323:42–46. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7303.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hróbjartsson A, Thomsen AS, Emanuelsson F, et al. Observer bias in randomized clinical trials with time-to-event outcomes: Systematic review of trials with both blinded and non-blinded outcome assessors. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43:937–948. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Berger VW, Exner DV. Detecting selection bias in randomized clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1999;20:319–327. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(99)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Altman DG, Bland JM. Statistics notes. Treatment allocation in controlled trials: Why randomise? BMJ. 1999;318:1209. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7192.1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Altman DG, Schulz KF. Statistics notes: Concealing treatment allocation in randomised trials. BMJ. 2001;323:446–447. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7310.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Berger VW, Christophi CA. Randomization technique, allocation concealment, masking, and susceptibility of trials to selection bias. J Mod Appl Stat Methods. 2003;2:80–86. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schulz KF. Subverting randomization in controlled trials. JAMA. 1995;274:1456–1458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dossing A, Tarp S, Furst DE, et al. Interpreting trial results following use of different intention-to-treat approaches for preventing attrition bias: A meta-epidemiological study protocol. BMJ Open. 2014;4 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]