Abstract

Background

Households are important for SARS-CoV-2 transmission due to high intensity exposure in enclosed spaces over prolonged durations. We quantified and characterized household clustering of COVID-19 cases in Fulton County, Georgia.

Methods

We used surveillance data to identify all confirmed COVID-19 cases in Fulton County. Household clustered cases were defined as cases with matching residential address. We described the proportion of COVID-19 cases that were clustered, stratified by age over time and explore trends in age of first diagnosed case within households and subsequent household cases.

Results

Between June 1, 2020 and October 31, 2021, 31,449(37%) of 106,233 cases were clustered in households. Children were the most likely to be in household clusters than any other age group. Initially, children were rarely (∼ 10%) the first cases diagnosed in the household but increased to almost 1 of 3 in later periods.

Discussion

One-third of COVID-19 cases in Fulton County were part of a household cluster. Increasingly children were the first diagnosed case, coinciding with temporal trends in vaccine roll-out among the elderly and the return to in-person schooling in Fall 2021. Limitations include restrictions to cases with a valid address and unit number and that the first diagnosed case may not be the infection source for the household.

Key words: Covid-19, Surveillance, Household transmission

Background

Understanding the spread of SARS-CoV-2 has been of critical importance [1], [2], [3], [4], [5]. From the perspective of public health policy and practice, identifying high-risk settings where COVID-19 transmission occurs provides important insights for targeting interventions such as contact tracing and directed testing efforts to reduce further disease spread. Despite intense scrutiny and high public interest in large superspreader events [6,7], smaller clusters of household cases have collectively more impact on total case counts. For example, investigations of the initial SARS-CoV-2 outbreak in Wuhan, China found that 78%–85% of infection clusters occurred in families [8], a trend that continued even after relaxation of the most stringent lockdown measures that confined cases and their contacts at home [9].

Household contacts are particularly vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 transmission. Household members experience high intensity exposure over prolonged durations and share enclosed and, at times, crowded living environments [10] – factors that together increase the probability of transmission from an infected individual to a susceptible household contact [11], [12], [13]. While proper adherence to non-pharmaceutical interventions such as mask-wearing and social distancing can reduce community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], consistently adopting such stringent preventative measures is difficult in practice, particularly in a household. Furthermore, cases can be infectious prior to symptom-onset [21], which precludes index household cases from taking early preventative measures to protect household members. Several systematic reviews drawing data from multiple countries highlight the significance of household transmission in sustaining the COVID-19 pandemic. These reviews estimate the household secondary attack rate of the original variant to be between 16.4%–30% [22], [23], [24], [25], [26] and higher based on preliminary evidence for alpha (24.5% from meta-analysis of three studies[27]) and delta variants [28,29]. Finally, the household presents a unique social context where intergenerational contact between children, parents and grandparents is higher than other social settings, such as work and school; in those settings, individuals tend to be in contact with other individuals of similar age [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]. As such, households can be an important setting for transmission from children to older adults who have increased susceptibility [35] and heightened probability of severe disease [36].

Despite known heightened transmission between household members that may have increased susceptibility and the importance of households in the context of intergenerational transmission, there is limited quantification of the extent of household clustering of COVID-19 in the US. We sought to use surveillance data to quantify the extent of household clustering of COVID-19 among confirmed COVID-19 cases in Fulton County, Georgia. Fulton County, encompassing metropolitan Atlanta, is an urban county in Georgia with a population of 1.1 million. We postulate that household clustered cases continue to account for a substantial proportion of cases detected by routine surveillance. We further explore temporal trends in clustering, the distribution of household-clustered cases among key demographic groups and focus our analysis on age profiles of cases in household clusters, exploring trends in age of first diagnosed case within clusters and age patterns between first diagnosed case and subsequent household cases. Our analysis uniquely leverages a robust and large public health database of routinely-collected COVID-19 case data to identify temporally clustered cases residing at the same residential address and quantify household clustering behavior.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a retrospective cohort analysis of persons residing in Fulton County, Georgia, who were diagnosed with PCR-confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. We obtained data for COVID-19 cases from Georgia Department of Public Health's (DPH) State Electronic Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (SENDSS) for Fulton County between June 1, 2020 and October 31, 2021. Per the state's COVID-19 response statutes, all individuals with a positive diagnosis for SARS-CoV-2 must be notified to the Georgia DPH. All reported cases are captured by DPH into the SENDSS database. Cases prior to June 1, 2020 were excluded due to the limited availability of testing early in the pandemic where only those with selected risk factors (e.g., age), COVID-related symptoms, or known exposure were eligible for testing. These eligibility criteria were removed in Fulton County in early June 2020, such that all persons could access free testing, regardless of symptoms or risk factors. Cases after October 31, 2021 were excluded as cluster data are likely incomplete due to ongoing household transmission chains.

Definitions and outcome measures

To identify cases originating from the same household residence, we standardized addresses using a geocoder which cross-referenced the case addresses with the US Postal Service address database and only cases with a valid and complete residential address were retained. Multiple studies have characterized the importance of communal residences (e.g., Long-Term Care Facilities (LTCF) [37], correctional facilities [38,39], homeless shelters [40] and dormitories) for SARS-CoV-2 transmission and superspreading [1]. Individuals living in these specific communal locations represent a small proportion of the total population (∼0.75% in nursing homes or assisted living facilities [41,42], ∼0.9% in student housing [43], [44], [45], ∼0.63% incarcerated [46] and less than 1% in shelters or communal supportive housing [47,48]). Moreover, residents have shared living environments and personal relationships with other members of their living space in a way that is distinct from households and household members. We thus chose to focus our analysis on the extent of clustering among individuals living at household addresses who represent a larger proportion of the population., Addresses belonging to communal residential locations were thus excluded. Addresses belonging to multifamily housing units (such as apartments or other rental properties and housing developments) that were missing the unit number were excluded to prevent erroneously grouping cases from the same housing unit as from the same household. Sensitivity analysis was conducted among the full dataset which retained those excluded for missing unit number followed by a qualitative comparison with results from the main analysis.

Clustered cases were defined as cases with a perfectly matching standardized street address, including unit number for apartment complex addresses. Household clusters were defined as >2 COVID-19 cases residing at the same residential address with positive sample collection dates within 28 days of one another (Supplementary Figure 1). With a median incubation period estimated at 5.1 days [49] and a median infectious period estimated at between 7 and 10 days [50], the 28 days would cover two infectious periods, one incubation period, and a 3–4 day lag between symptom-onset and positive sample collection [51]. Given the high proportion of asymptomatic and undiagnosed COVID-19 cases, this would allow two diagnosed cases with one undiagnosed case in between them in the transmission chain to be classified as a single household cluster.

Variables collected during routine surveillance and utilized in this analysis were age, gender, race/ethnicity, address, symptom status, hospitalization, date of positive sample collection and date of symptom-onset. We estimated the extent of COVID-19 clustering among cases by calculating the proportion of all COVID-19 cases that belong to a household cluster, based on our operational definition of a cluster described above, stratified by age group, gender, race and/or ethnicity, symptom and hospitalization status, and over month of the pandemic. We computed statistics related to cluster characteristics including cluster size and duration between first and last diagnosed case within a cluster. We focus our analysis on patterns in age profiles of cases in household clusters by describing the distribution of the age of first diagnosed case within a household cluster over time and visualizing patterns between age group of first diagnosed case and age group of subsequent household cases. For the latter visualization, we expected age-specific relationships between first and subsequent cases within households to mirror the age-specific mixing patterns within household contacts documented in social mixing surveys [30].

This activity was determined to be consistent with public health surveillance activity as per title 45 code of Federal Regulations 46.102(l)(2). The Emory University institutional review board approved this activity with a waiver of informed consent.

Results

A total of 106,233 COVID-19 cases were reported in Fulton County between June 1, 2020 and October 31, 2021, of which 84,383 (79.4%) were included in our analysis. Reasons for exclusion include residing in a long-term care facility (N = 4540, 4.3%), addresses not matched to the geocoding database (N = 5991, 5.6%) due to missing or incomplete addresses (P.O box only or missing zip code) or major spelling errors, live in communal places (ex. correctional facilities, shelters or dorms) (N = 1509, 1.4%) and apartments with no unit number (N = 9, 810, 9.2%) (Supplemental Figure 2). Included individuals were similar to excluded individuals with respect to age, gender, race and/or ethnicity, symptom and hospitalization status (Supplemental Table 1). A majority of cases were female (N = 44,940; 53%), 14,726 (17%) were children aged 0–18 years and 10,555 (12%) were adults aged 60 years and above (Table 1 ). The largest racial and/or ethnicity group was black, non-Hispanic individuals (N = 38,128, 45%), followed by white, non-Hispanic individuals (N = 28,272, 34%) followed by Hispanic individuals of all races (N = 7776, 9%).

Table 1.

Association between demographic and clinical characteristics of confirmed COVID-19 cases and being part of an identified household clusters among cases with a valid household residential address and unit number (N = 84,383) – June 1, 2020 to October 31, 2021

| — | — | Total | Col% | HH-clustered individuals | % HH-clustered |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | — | 84,383 | – | 31,449 | 37 |

| Gender | Female | 44,940 | 53 | 16,944 | 38 |

| Male | 39,150 | 46 | 14,408 | 37 | |

| Missing | 293 | 0 | 97 | 33 | |

| Age group | 0–18 | 14,726 | 17 | 8089 | 55 |

| 19–29 | 18,647 | 22 | 5080 | 27 | |

| 30–39 | 16,125 | 19 | 4820 | 30 | |

| 40–49 | 13,050 | 15 | 5021 | 38 | |

| 50–59 | 11,254 | 13 | 4298 | 38 | |

| 60–69 | 6263 | 7 | 2418 | 39 | |

| 70 plus | 4292 | 5 | 1715 | 40 | |

| Missing | 26 | 0 | 8 | 31 | |

| Race/ethnicity | Asian, NH | 3503 | 4 | 1693 | 48 |

| Black, NH | 38,128 | 45 | 13,339 | 35 | |

| White, NH | 28,272 | 34 | 10,038 | 36 | |

| Hispanic, all | 7776 | 9 | 3769 | 48 | |

| Other, NH | 2678 | 3 | 1073 | 40 | |

| Missing | 4026 | 5 | 1537 | 38 | |

| Symptom status | No | 8812 | 10 | 3299 | 37 |

| Yes | 49,247 | 58 | 18,468 | 38 | |

| Unknown | 26,324 | 31 | 9682 | 37 | |

| Hospitalized | No | 46,602 | 55 | 17,974 | 39 |

| Yes | 4758 | 6 | 1476 | 31 | |

| Unknown | 33,023 | 39 | 11,999 | 36 |

Among these included cases (N = 84,383), 37,432 (44%) had an address that matched at least one other case; 31,449 (37%) (Table 1) had positive sample collection date within 28 days of another household case. The age-stratified probability of being part of a household cluster among those with valid household addresses followed a U-shaped trend where children aged 0–18 years were most likely to be part of a household cluster (55%), followed by adults aged 40 years and above (39%), with young adults between 19 and 39 years the least likely to be in a household cluster (28%). We observed higher clustering among Hispanic (47%) and non-Hispanic, Asian (47%) persons compared to non-Hispanic black (33%) and non-Hispanic white (35%) persons. There are no differences in clustering by gender or reported symptom status.

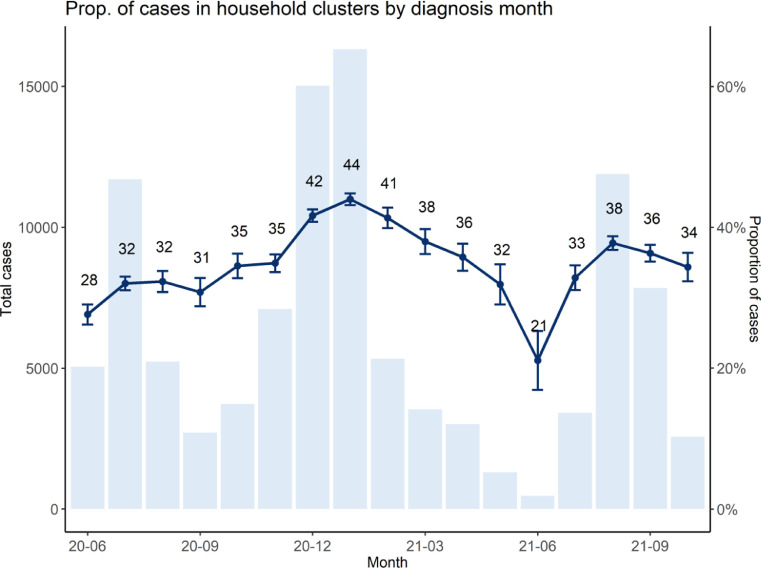

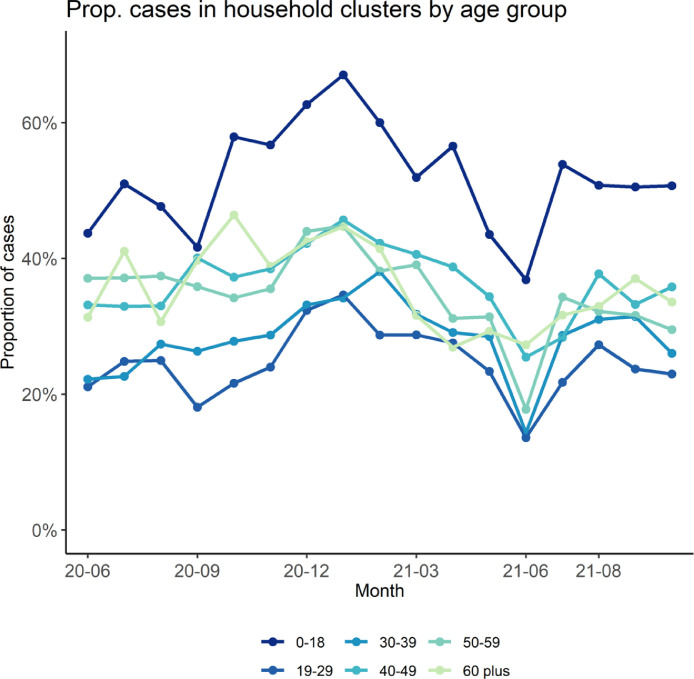

We observed temporal trends in household clustering. The proportion of cases identified in household clusters fluctuated between 30% and 40% each month. Clustering increased between November 2020 to January 2021, steadily declined between Feb to June 2021, arrived at a low in June 2021, and has since rebounded to earlier levels (Fig. 1 ). Trends in probability of household clustering by age of case (e.g., children aged 0–18 years most likely to be in household clusters) have stayed consistent over the course of the pandemic (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Temporal trend in the proportion of diagnosed cases in Fulton County, Georgia (with a valid residential household address and a valid unit number), that were identified in household clusters stratified by the month of positive sample collection date (dark blue line), with 95% confidence interval around the point estimate. A bar chart of monthly confirmed cases in Fulton County is provided for reference. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Fig. 2.

Temporal trend in the proportion of diagnosed cases (with a valid residential household address and a valid unit number) in Fulton County, Georgia, that were identified in household clusters stratified by month of positive sample collection date (x-axis) and by age group.

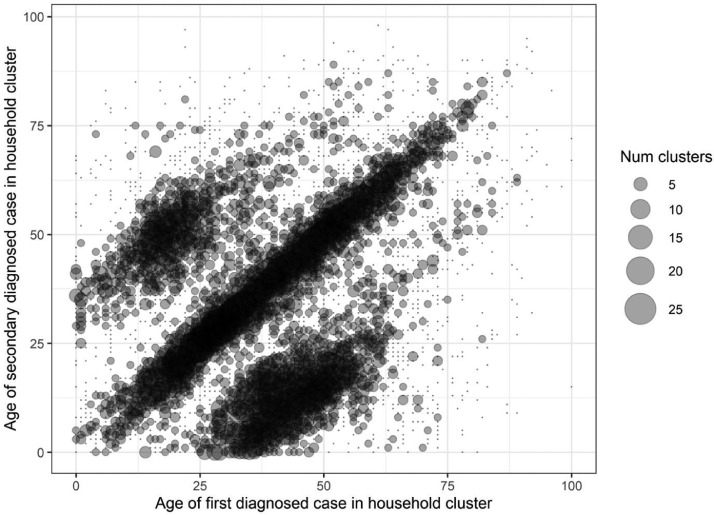

Among 12,955 household clusters, the majority of clusters had 2 individuals (N = 9216 clusters, 71%), although some clusters had ≥6 individuals (N = 122, 1.0%; Table 2 ). Excluding clusters with multiple cases diagnosed on the first day, the first diagnosed case was 0–18 years in 1314 (15%) of clusters, 19–29 years in 1614 (19%) of clusters, 30–39 years in 1592 (18%) of clusters, 40–49 years in 1593 (18%) of clusters 50–59 years in 1336 (15%) of clusters and above 60 years in 1235 (14%) of clusters. The proportion of children diagnosed as the first case in the cluster increased from 11% in February 2021 to a high of 31% in August 2021 (Supplemental figure 5). In contrast, proportion of cases greater than 50 years of age diagnosed as the first case in the cluster decreased during the same time period from 35% to 19%. Clusters most often consisted of individuals in the same age group, as shown by the high density of bubbles along the diagonal in the bubble plot counting clusters by age of first diagnosed case and age of subsequent diagnosed cases in the household (Fig. 3 ). Two other diagonals are present. One below the main diagonal consisting of 25–50-year-old first diagnosed case clustered with 0–20-year-old subsequent household cases and another diagonal above the main diagonal consisting of 10–25-year-old first diagnosed case clustered with 40–55-year-old secondary cases.

Table 2.

Characteristics of household clusters (N = 12,955) in Fulton County – June 1, 2020 to October 31, 2021

| — | — | Total HH Clusters (N = 12,955) | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of individuals in cluster | 2 | 9216 | 71 |

| 3–5 | 3617 | 28 | |

| 6+ | 122 | 1 | |

| Days between first and last diagnosis in cluster | 0 | 3398 | 26 |

| 1–7 days | 6198 | 48 | |

| 8–14 days | 2166 | 17 | |

| 15–28 days | 1110 | 9 | |

| 29 or more days | 83 | 1 | |

| Clusters with more than one case on first date of diagnosis | — | 4268 | 33 |

| Age of first diagnosed case in cluster | 0–18 yrs | 1314 | 15 |

| 19–29 yrs | 1614 | 19 | |

| 30–39 yrs | 1592 | 18 | |

| 40–49 yrs | 1593 | 18 | |

| 50–59 yrs | 1336 | 15 | |

| 60 yrs and above | 1235 | 14 |

Fig. 3.

Bubble plot of distribution of clusters across different cluster age profiles where the x-axis is the age of first diagnosed case in the household cluster, y-axis is the age of subsequent secondary diagnosis in the household cluster, the size of bubble represents number of clusters by each age pairing of first diagnosed case and subsequent cases and the density representing more common cluster age profiles (on the diagonal between cases of the same age in the same household and the two off-diagonal “wings” representing intergenerational clusters).

In the sensitivity analysis that included individuals residing in multiunit addresses without a unit number, the proportion of individuals with the same address rises to 52%; however, we cannot differentiate between linked clusters and unconnected individuals from the same complex diagnosed at the same time by chance. Time periods, race and/or ethnicity and age groups with higher clustering in the main analysis are the same as those in the sensitivity analysis and the distribution of the age group of the first diagnosed case is also similar between sensitivity analysis and main analysis (Supplemental figure 6).

Discussion

Over one-third of reported COVID-19 cases in Fulton County between June 2020 and August 2021 were part of a household cluster. The probability that children aged 0–18 years belonged to a household cluster was higher than the probability for any other age group. Moreover, children increasingly represented the first positive detected case in the household, rising from 11% in February 2021 to 31% in August 2021. Age patterns between first and subsequent cases within household clusters mirror household social mixing patterns where clusters of individuals of the same age are most common followed by intergenerational clusters between parents and children. High probability of household clustering and cross-age transmission underscore the importance of contact tracing, testing, and quarantining of household contacts and the need to emphasize strategies such as self-testing of household members for early identification of infections.

Findings from our study adds evidence to the important role of household clustering in shaping the course of the pandemic. Our study results are comparable to those reported by Massachusetts State Department of Public Health in their “cluster-busting” strategy for COVID-19 control [51] where a third of cases reported between September and October 2020 belonged to a household cluster [52]. Small reductions in household transmission have potential to meaningfully reduce overall cases. At the population-level, a larger proportion of close proximity human contact occurs within households [53], [54], [55] rather than in community settings such as schools, nursing homes or large gatherings notorious for superspreading. While households rarely become superspreading locations, the majority of Americans (72%) [56] live with at least one other individual who would be highly exposed to an index household case.

The higher proportion of children in household clusters likely reflects higher probability of living in a home with another individual, either other children or adult caregivers. Increased probability of child cases as the first diagnosed case in household clusters starting March 2021 coincide with vaccination of older age groups. Further increases starting in August 2021 coincide with the return-to-school of largely unvaccinated children for the Fall 2021 semester. Collectively, these trends suggest that children are increasingly important for transmission within households despite lower infectiousness compared to adults [57,58]. Our bubble plot of age profiles within household clusters show that clusters are dominated by those of individuals of the same age, likely couples, roommates or sibling, and those in intergenerational age groups, likely parent and child. These findings suggest the importance of age-specific mixing patterns in determining the magnitude of age-specific clustering within households.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, household-level interventions to reduce household clustering should be further incorporated into the existing response. For example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends household index cases quarantine in a separate bedroom and bathroom and limit sharing of food and kitchenware [59]. Yet distancing and safe quarantine are not feasible within all households and an estimated 20% of households did not have sufficient bedrooms and bathrooms to safely quarantine an infected person at home [60]. Vaccination remains the single most effective intervention at preventing infection and severe disease [61]; however, while coverage among children is still low [62], additional interventions should be explored such as rapid antigen tests for all household members to facilitate early diagnosis or provision of a box of surgical or KN95 masks to increase safer household contact and prevent onward transmission outside of the household.

We report several limitations. Our analysis used surveillance data which is known to under-ascertain COVID-19 cases, especially during the early days of the pandemic [63]. The proportion of cases in household clusters may be overestimated if individuals with known household exposure are more likely to present for testing or if individuals living alone are less likely to test given their ability to isolate alone. Proportion of cases in household clusters may be underestimated if those with confirmed household exposure are less likely to test if they believe knowing their infection status will have little impact on treatment course and outcome, especially if a household member had symptoms that were resolved prior to the diagnosis of a secondary case. Changing testing and screening strategies may also affect age-related clustering trends. For a substantial number of cases living in multiunit complexes without a reported unit number, we could not determine whether cases with the same address were linked clusters or were unrelated and arose by chance in the same complex and time period. We chose to restrict our analysis to those with a valid address and unit number if living in multiunit complexes. We conducted sensitivity analyses with the unrestricted datasets to understand the extent of potential biases and find that the proportion clustered was higher (52%), but the broad trends in our results still held. Furthermore, we do not know if members within household clusters infected each other or whether some subsequent cases were infected from the community. Finally, the first diagnosed case may not represent the source of infection for the household.

The unique advantage of our study is that we use rigorous methods to identify cases from surveillance data residing at the same residential address, producing the first estimates of the extent of household clustering over time in a large, diverse metropolitan area. No other study has used public health surveillance data to systematically track temporal and demographic trends of household clusters of COVID-19 in the US. The use of routinely collected surveillance data provides a more accessible, rapid approach for health departments to evaluate household clustering and inform interventions. In addition, our study finds evidence of higher probability of household clustering among children and Hispanic and Asian persons and early indication of increases in the proportion of household clusters with a child as the first diagnosed case.

In conclusion, we used residential address to identify cases temporally clustered within a household. Our analysis found that between June 1, 2020 and October 31, 2021, 37% of reported cases in Fulton County, Georgia belonged to household clusters. Our findings complement the high household secondary attack rates found in cohort studies of household transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and further quantifies the extent of household clustering at a population level. Our results support the consideration of improved public health response to reducing household clustering and within-household transmission such as within-household masking and rapid testing for household contacts for increased public health impact in controlling COVID-19.

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.09.010.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Leclerc Q.J., Fuller N.M., Knight L.E., Funk S., Knight G.M, CCMID COVID-19 Working Group What settings have been linked to SARS-CoV-2 transmission clusters? Wellcome open research. 2020;5(83) doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15889.1. https://wellcomeopenresearch.org/articles/5-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu Y., Eggo R.M., Kucharski A.J. Secondary attack rate and superspreading events for SARS-CoV-2. The Lancet. 2020;395:e47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30462-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majra D., Benson J., Pitts J., Stebbing J. SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) superspreader events. Journal of Infection. 2021;82:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Furuse Y., Sando E., Tsuchiya N., et al. Clusters of Coronavirus Disease in Communities, Japan, January–April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2176–2179. doi: 10.3201/eid2609.202272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi Y.J., Park M Jeong, Park S.J., et al. Types of COVID-19 clusters and their relationship with social distancing in the Seoul metropolitan area, South Korea. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2021;106:363–369. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamner L., Dubbel P., Capron I., et al. High SARS-CoV-2 Attack Rate Following Exposure at a Choir Practice — Skagit County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:606–610. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lemieux J.E., Siddle K.J., Shaw B.M., et al. Phylogenetic analysis of SARS-CoV-2 in Boston highlights the impact of superspreading events. Science. 2021;371:eabe3261. doi: 10.1126/science.abe3261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . 2020. WHO china joint mission on covid19 final report. Published online. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cluster infections play important roles in the rapid evolution of COVID-19 transmission: a systematic review. Elsevier Enhanced Reader. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.07.073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Cevik M., Marcus J., Buckee C., Smith T. SARS-CoV-2 transmission dynamics should inform policy. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2020 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1442. Published online September 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo L., Liu D., Liao X., et al. Contact Settings and Risk for Transmission in 3410 Close Contacts of Patients With COVID-19 in Guangzhou, China. Ann. Intern. Med..:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Ng O.T., Marimuthu K., Koh V., Pang J., Linn K.Z., Lee V. SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and transmission risk factors among high-risk close contacts: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infectious DIseases. 21:333–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Bi Q., Wu Y., Mei S., et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20:911–919. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brauner J.M., Mindermann S., Sharma M., et al. Inferring the effectiveness of government interventions against COVID-19. Science. 2020:eabd9338. doi: 10.1126/science.abd9338. Published online December 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guy G.P., Massetti G.M., Sauber-Schatz E. Mask Mandates, On-Premises Dining, and COVID-19. JAMA. 2021 doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.5455. Published online April 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Talic S., Shah S., Wild H., Ilic D. Effectiveness of public health measures in reducing the incidence of covid-19, SARS-CoV-2 transmission, and covid-19 mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2021:n2997. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n2997. Published online December 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andrasfay T., Wu Q., Lee H., Crimmins E.M. Adherence to Social-Distancing and Personal Hygiene Behavior Guidelines and Risk of COVID-19 Diagnosis: evidence From the Understanding America Study. Am J Public Health. 2022;112:169–178. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2021.306565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abaluck J., Kwong L.H., Styczynski A., Ashraful H., Alamgir K., Ellen B., et al. Impact of community masking on COVID-19: a cluster-randomized trial in Bangladesh. Science. 2022;375:eabi9069. doi: 10.1126/science.abi9069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leech G., Rogers-Smith C., Monrad J.T., Sandbrink J.B., Snodin B., Zinkov R., et al. Mask wearing in community settings reduces SARS-CoV-2 transmission. PNAS. 2022;119:9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2119266119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brooks J.T., Butler J.C. Effectiveness of Mask Wearing to Control Community Spread of SARS-CoV-2. JAMA. 2021;325:998. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.1505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z., Chu R., Gong L., et al. The assessment of transmission efficiency and latent infection period in asymptomatic carriers of SARS-CoV-2 infection. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;99:325–327. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Curmei M., Ilyas A., Evans O., Steinhardt J. Estimating Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2. medRXiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.23.20111559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Madewell Z.J., Yang Y., Longini I.M., Halloran M.E., Dean N.E. Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung H.F., Martinez L., Alarid-Escudero F., Salomon J.A., Studdert, D.M., Andrews J.R., et al. The household secondary attack rate of SARS-CoV-2: a rapid review. Clinical Infectious Diseases. Published online October 12, 2020:ciaa1558. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa1558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Koh W.C., Naing L., Chaw L., Rosledzana M., Alikhan M.F., Jamaludin S.A., et al. What do we know about SARS-CoV-2 transmission? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the secondary attack rate and associated risk factors. PLoS ONE. 2020 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shah K., Saxena D., Mavalankar D. Secondary attack rate of COVID-19 in household contacts: a systematic review. QJM. 2020;113(12):841–850. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Madewell Z.J., Yang Y., Longini I.M., Halloran M.E., Dean N.E. Factors Associated With Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2: an Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.22240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Public Health England. SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation. Published online June 3, 2021:66.

- 29.Dougherty K., Mannell M., Naqvi O., Matson D., Stone J. SARS-CoV-2 B1.617.2 (Delta) Variant COVID-19 Outbreak Associated with a Gymnastics Facility — Oklahoma, April–May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:1004–1007. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7028e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mossong J., Hens N., Jit M., Beutels P., Auranen K., Mikolajczyk R, et al. Social Contacts and Mixing Patterns Relevant to the Spread of Infectious Diseases. Riley S, ed. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e74. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu C.Y., Berlin J., Kiti M.C., Fava E.D., Grow A, Zagheni E, et al. Rapid review of social contact patterns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Epidemiology. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2021.03.12.21253410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jarvis C.I., Van Zandvoort K., Gimma A., Prem K., Klepac P., Rubin J.G., et al. Quantifying the impact of physical distance measures on the transmission of COVID-19 in the UK. BMC Med. 2020;18:124. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01597-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coletti P., Wambua J., Gimma A., Willem L., Vercurysse S., Vanhoutte B., et al. CoMix: comparing Mixing Patterns in the Belgian Population during and after Lockdown. Medrxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.08.06.20169763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J., Klepac P., Read J.M., Rosello A., Wang X., Lai S., et al. Patterns of human social contact and contact with animals in Shanghai, China. Sci Rep. 2019;9:15141. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51609-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davies N.G., Kucharski A.J., Eggo R.M., Gimma A., CMMID COVID-19 Working Group. Edmunds W.J. The Effect of Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions on COVID-19 Cases, Deaths and Demand for Hospital Services in the UK: a Modelling Study. Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.01.20049908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Verity R., Okell L.C., Dorigatti I., Winskill P., Whittaker C., Imai N., et al. Estimates of the severity of coronavirus disease 2019: a model-based analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20:669–677. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30243-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham N.S.N., Junghans C, Downes R, Sendall C., Lai H., McKirdy A., et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection, clinical features and outcome of COVID-19 in United Kingdom nursing homes. Journal of Infection. 2020;81(3):411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.05.073. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Njuguna H., Wallace M., Simonson S., Tobolowsky F.A., James A.E., Bordelon K., et al. Serial Laboratory Testing for SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Incarcerated and Detained Persons in a Correctional and Detention Facility — Louisiana, April–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:836–840. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6926e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hagan L.M., Williams S.P., Spaulding A.C., Toblin R.L., Figlenski J., Ocampo J., et al. Mass Testing for SARS-CoV-2 in 16 Prisons and Jails — Six Jurisdictions, United States, April–May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:1139–1143. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6933a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohsenpour A., Bozorgmehr K., Rohleder S., Stratil J., Costa D. SARS-Cov-2 prevalence, transmission, health-related outcomes and control strategies in homeless shelters: systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2021;2021:38. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Institute of Medicine (US) Food Forum Providing Healthy and Safe Foods As We Age: workshop Summary. Physiology and Aging. 2010;3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK51842/?report=reader Available at: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Total Number of Residents in Certified Nursing Facilities. KFF. Published August 23, 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. Available at: https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/number-of-nursing-facility-residents.

- 43.(National Center for Education Statistics); 2022. Education statistics surveys and program areas at nces.https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/SurveyGroups.asp?group=2 Accessed September 6Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 44.U.S. student housing supply by volume of beds 2010-2021. Statista. Accessed September 6, 2022. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1013921/student-housing-supply-usa-by-number-of-beds

- 45.Understanding College Affordability. Accessed September 6, 2022. Available at: http://urbn.is/2nPYxhg

- 46.Gramlich J. Pew Research Center; 2022. America's incarceration rate falls to lowest level since 1995.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/08/16/americas-incarceration-rate-lowest-since-1995 Accessed September 6Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 47.HUD.gov /U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD); 2022. HUD releases 2021 annual homeless assessment report part 1.https://www.hud.gov/press/press_releases_media_advisories/hud_no_22_022 Published February 4, 2022. Accessed September 6Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 48.Number of beds for homeless people in the U.S. by housing type 2020. Statista. Accessed September 6, 2022. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/962246/number-beds-homeless-people-us-housing-type

- 49.McAloon C., Collins Á., Hunt K., Barber A., Byrne A.W., Butler F., et al. Incubation period of COVID-19: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of observational research. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Byrne A.W., McEvoy D., Collins A.B., Hunt K., Casey M., Barber A., et al. Inferred duration of infectious period of SARS-CoV-2: rapid scoping review and analysis of available evidence for asymptomatic and symptomatic COVID-19 cases. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Massachusetts Department of Public Health COVID-19 Dashboard: Weekly COVID-19 Public Health Report. Published online April 1, 2021. Available at: https://www.mass.gov/doc/weekly-covid-19-public-health-report-april-1-2021/download.

- 52.Boston Herald; 2021. Majority of massachusetts coronavirus clusters are from households.https://www.bostonherald.com/2020/10/30/majority-of-massachusetts-coronavirus-clusters-are-from-households Published October 30, 2020. Accessed July 4Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu C.Y., Berlin J., Kiti M.C., del Fava E., Grow A., Zagheni E., et al. Rapid Review of Social Contact Patterns During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Epidemiology. 2021;32:781–791. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000001412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kiti M.C., Aguolu O.G., Liu C.Y., Mesa A.R., Regina R., Woody M., et al. Social contact patterns among employees in 3 U.S. companies during early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic, April to June 2020. Epidemics. 2021;36 doi: 10.1016/j.epidem.2021.100481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feehan D.M., Mahmud A. Quantifying interpersonal contact in the United States during the spread of COVID-19: first results from the Berkeley Interpersonal Contact Study. Nature Communications. 2021:12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-20990-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Distribution of U.S. households by size 1970-2020. Statista. Published 2021. Accessed August 15, 2021. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/242189/disitribution-of-households-in-the-us-by-household-size

- 57.Chu V.T., Yousaf A.R., Chang K., Schwartz N.G., McDaniel C.J., Lee S.H., et al. Household Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from Children and Adolescents. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;385(10):954–956. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2031915. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guilamo-Ramos V., Benzekri A., Thimm-Kaiser M., Hidalgo A., Perlman D.C. Reconsidering Assumptions of Adolescent and Young Adult Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Transmission Dynamics. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021;73(Supplement_2):S146–S163. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.CDC. COVID-19 and Your Health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published February 11, 2020. Accessed August 15, 2021. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/if-you-are-sick/care-for-someone.html.

- 60.Sehgal A.R., Himmelstein D.U., Woolhandler S. Feasibility of Separate Rooms for Home Isolation and Quarantine for COVID-19 in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174:127–129. doi: 10.7326/M20-4331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thompson M.G., Burgess J.L., Naleway A.L., Tyner H.L., Yoon S.K., Meece J., et al. Interim Estimates of Vaccine Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 COVID-19 Vaccines in Preventing SARS-CoV-2 Infection Among Health Care Personnel, First Responders, and Other Essential and Frontline Workers — Eight U.S. Locations, December 2020–March 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70:495–500. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7013e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Murthy B.P., Zell E., Saelee R., Murthy N., Meng L., Meador S., et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Coverage Among Adolescents Aged 12–17 Years — United States, December 14, 2020–July 31, 2021. MMWR. 2021;70(35):1206–1213. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7035e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chamberlain A.T., Toomey K.E., Bradley H., Hall E., Fahimi M., Lopman B.A., et al. Cumulative incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infections among adults in Georgia, USA, August-December 2020. J Infect Dis. 2022;225(3):396–403. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiab522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.