Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic emerged to be a fertile ground for age‐based prejudice and discrimination. In particular, a growing literature investigated ageism towards older people at the individual and the interpersonal level, providing evidence of its prevalence, antecedents and negative consequences. However, less much is known on the phenomenon at the intergroup level. To fill this gap, the present correlational research investigated the effects of younger people's endorsement of ageism towards older people on the attitude towards COVID‐19 restriction measures primarily targeted to older (vs. younger) population. In the autumn of 2020, five hundred and eighty‐two Italian participants (83.3% females; M age = 20.02, SD age = 2.83) completed an online questionnaire. Results revealed that the younger people's endorsement of ageism towards older people increased the attribution of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to older (vs. younger) people, which, in turn positively affected the attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation and support for selective lockdown on older population only. The main contributions of the study, limitations, future research directions, and practice implications are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

The current COVID‐19 pandemic has been recognized as one of the most significant public health issues in the last century, bringing about important challenges not only to the healthcare systems but also to the economic and societal ones worldwide. In the face of such a situation, academics have started to investigate the potential impacts of the pandemic on people's attitudes at multiple levels. This line of research indicated that the COVID‐19 pandemic is a fertile ground for scapegoating and prejudice not only towards several ethnic minorities (Esses & Hamilton, 2021) but also towards age‐based categories such as older people (for a literature review see, Silva et al., 2021). The emphasis posed on the role of age in susceptibility and mortality rates to COVID‐19 has been accompanied by the representations of older population as the most vulnerable and useless segment of the society (Ayalon, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2021). Therefore, the public discourses erroneously instigated that COVID‐19 is a problem of older population, questioned about older adults’ contribution to the society, and exacerbated age‐division and intergenerational conflicts (Ayalon et al., 2020). Despite a growing body of studies investigated different aspects of ageism towards older population – such as its prevalence, antecedents, and consequences – the available research is scant as compared to other forms of prejudice and is mostly focused on the individual (e.g., the effects of ageism on older adults’ health conditions and self‐esteem) and the interpersonal (e.g., the use of baby talk in interacting with older adults) level of analysis (for reviews, see North & Fiske, 2012; Raina & Balodi, 2014), leaving the intergroup – or intergenerational – level of ageism towards older populations understudied (for recent exceptions see, Kanik et al., 2022; Sutter et al., 2022). However, as demonstrated by the broader sociopsychological literature on intergroup conflict, the tension between groups detrimentally affects people's lives. Considering that the global population is increasingly growing older, and that older individuals are at higher risk of violation of human rights during the pandemic (Previtali et al., 2020), investigating the intergenerational conflict is of particular relevance to avoid discrimination and social injustices (North & Fiske, 2012). Thus, to fill this gap, the specific aim of the present correlational research was to investigate in Italy, the effects of younger people's endorsement of ageism towards older people on the attitude towards the adoption of COVID‐19 restriction measures and prescriptions primarily targeted to older (vs. younger) population.

Ageism towards older people

People automatically categorize others based on visible physical cues. Like ethnicity and gender, age is among the most crucial social markers in social categorization, impression formation, and social behavior processes (Ng, 1998; North & Fiske, 2012). Relying on visible cues is a mental short cut that rapidly guides people in social world. However, it can also lead to prejudice and discrimination towards specific groups of individuals.

The prejudice towards a group based on the age of that group has been termed ageism and it can potentially affect any age group (Butler, 1969). Ageism encompasses stereotypes, affective states, and discrimination against the target (Ng, 1998; Raina & Balodi, 2014). Although the boundaries between age groups are often flexible, context‐dependent, and represent an oversimplification of aging processes, in the present research we relied on one of the age criteria that research has traditionally adopted, identifying people under the age of 35 as young and people above the age of 65 as older (Contoli et al., 2016; Mucchi Faina, 2013; Orimo et al., 2006).

A huge socio‐psychological literature demonstrated that ageism towards older people is widespread among countries and cultures (e.g., Germany in Jelenec & Steffens, 2002; for reviews of international literature, see Levy & Banaji, 2002; Levy & Macdonald, 2016; Marques et al., 2020; Raina & Balodi, 2014).

Stereotypes about older people are ambivalent and, thus, encompass positive and negative traits, such as being perceived as poor in health and fragile, warm but incompetent, inflexible and lacking of competitiveness but friendly and lovely grandparents, wise but dispensable individuals unable to contribute to society (e.g., review of international literature in Cuddy & Fiske, 2002; Fiske et al., 2002; Levy & Banaji, 2002; Raina & Balodi, 2014). The normalization and perpetuation of stereotypes is facilitated by mass media too, which often portray older individuals in a stereotyped manner as narrow‐minded, fragile, diseased, and incompetent (Cuddy et al., 2005; Levy and Banaji, 2002; American participants in Lytle & Levy, 2019; Raina & Balodi, 2014).

As for discrimination against older people, it emerged in a variety of life‐domains such as interpersonal communications, politics, workplace, and healthcare (for reviews of international literature see Lytle & Levy, 2019; Mucchi Faina, 2013; Ng, 1998; Raina & Balodi, 2014; for recent research on discrimination during the pandemic see Lloyd‐Sherlock et al., 2022). In workplace, older people are devalued in their competence and potentials and, thus, they often experience a lack of work opportunities (e.g., Abrams et al., 2016; systematic review conducted on data from 45 countries in Chang et al., 2020; North & Fiske, 2016; Raina & Balodi, 2014). In particular, older workers and job applicants are perceived to be higher on warmth, loyalty, and stability but simultaneously lower on competence, productivity, less suitable for promotion as compared to younger workers and job applicants, and less likely to be hired even when the job requires warmth‐related capabilities (review of international literature in Christian et al., 2014; Cuddy & Fiske, 2002; Swiss participants in Krings et al., 2011). In healthcare domain, older people are infantilized, threated as others‐dependent, in a less respectful and supportive manner, denied access to health services and excluded from health research (Chang et al., 2020; Christian et al., 2014; Cuddy et al., 2005; Raina & Balodi, 2014).

Interestingly, older people themselves internalize stereotypes about their own age group (e.g., American participants in Hummert et al., 1994; Levy & Banaji, 2002; Nosek et al., 2002) with the internalization of the stereotypical beliefs, in turn, longitudinally and negatively affecting people's self‐concept as they get old (Ayalon et al., 2020; Levy, 2009; German participants in Rothermund & Brandtstädter, 2003). Furthermore, experiencing ageism can worsen older people's psycho‐physical health through the mediation of psychological (e.g., reduced self‐efficacy), behavioral (e.g., less healthy behaviors), and physiological (e.g., change in the level of C‐reactive protein, that is a stress biomarker of inflammation) processes resulting in physical and mental illness, cognitive impairment, reduced longevity, and depressive symptoms (for a review see, Chang et al., 2020).

Sociopsychological perspectives on ageism causes

Several sociopsychological perspectives have been advanced about the roots of ageism towards older people. Individual theories, for instance, have explained ageism as an ego‐protective strategy (Marques et al., 2020; North & Fiske, 2012). Accordingly, the threat of death (Terror Management account; Greenberg et al., 2017) or the need to maintain a positive social identity exacerbating the differences between age‐groups (Social Identity account, Kite et al., 2005) pushes younger people to distance themselves from older people. Instead, sociocultural theories have emphasized how contemporary society's structure encourages ageism (Marques et al., 2020; North & Fiske, 2012). Accordingly, older people are perceived as a marginal segment of society (e.g., retirees) and as a low status group lacking either competitiveness (Stereotype Content account; Cuddy et al., 2005) or agency and social value (Social Role account; Kite & Wagner, 2004). Albeit not directly investigated from an intergroup perspective, similarly to other forms of prejudice, ageism has been explained as the result of tension between groups (North & Fiske, 2012). When the resources are scarce, intergroup conflict might arise with perceived symbolic and realistic threat increasing hostility and disputes over the resources’ allocation among groups (Sherif et al., 1961; Stephan & Stephan, 2017). While realistic threats regard tangible harms (e.g., economic power and physical or material wellbeing), symbolic threats refer to intangible harms (e.g., differences in values, morality, and norms) to the ingroup (Stephan & Stephan, 2017). Public discourses and media portrayals that accentuate the distinctions between the groups exacerbate this conflict. Therefore, members of the stigmatized outgroup are perceived negatively, evoke threat, and are the target of subtle and blatant forms of prejudice and discrimination (e.g., Becker et al., 2011; Conzo et al., 2021; Glick, 2002). Consistently, it has been proposed that older people, by prorogating their retirement, trying to look younger, and having access to abundant public funding, can constitute a threat for younger generation, and thus, they are likely to face backlash from younger people who desire to have access to such societal resources (North & Fiske, 2012).

Ageism and intergenerational conflict during the COVID‐19 pandemic

Research from multiple disciplines clearly demonstrated that the COVID‐19 pandemic has exacerbated prejudice towards older population (Fraser et al., 2020; analysis of tweets in the English language in Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2021; Ng et al., 2022; review of international literature in Silva et al., 2021; Swift & Chasteen, 2021) with negative consequences for their wellbeing (Cohn‐Schwartz et al., 2022; Derrer‐Merk et al., 2022). Ng et al. (2021) analyzed aging narratives before and during the pandemic (from October 2019 to May 2020) in 20 countries, revealing that ageism registered an alarming acceleration. Consistently, an increasing number of research documented the prevalence of negative and ageist representations of older people during the pandemic worldwide. These representations encompass offensive, stereotyped, and derogatory memes and hashtags (e.g., #boomerremover, review of international literature in Brooke & Jackson, 2020; analysis of tweets in the English language in Skipper & Rose, 2021), as well as contents depicting older people as a homogenously frail group and as the cause of the spread of the virus (e.g., Fraser et al., 2020; Jimenez‐Sotomayor et al., 2020). Furthermore, although it is well‐established that all age groups are at risk of developing COVID‐19 disease, the media has strongly emphasized that older populations are at higher risk, instigating the idea that COVID‐19 is a disease of only the older individuals (review of international literature in Previtali et al., 2020; Swift & Chasteen, 2021). Additionally, public institutions and some politicians strengthened prejudice against older people with their insulting remarks and ill‐advised decisions. This is the case of several politics around the world, who declared – more or less explicitly – that older people are useless to the productive efforts of the country and, thus, they should sacrifice themselves by self‐isolating to let their countries move on. For instance, as for the need to re‐open the economy of USA, Texas Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick declared that – as an older person – he would prefer to risk death rather than to damage the economy of his country and added that most of grandparents would be of the same mind (Ayalon, 2020; Becket, 2020). The initial response of the UK government to the pandemic was to suggest to people older than 70 years old to self‐isolate for 4 months, while the other age segments of society could continue their usual life (Ayalon, 2020; Sparrow, 2020). In Italy, where 5% of the over 65 years old population is still working (ISTAT, 2020, 2021), the Italian Governor Giovanni Toti called for limitations to be targeted on older population, described as not indispensable for the economy and productive system of the country (ANSA, 2020).

Additionally, the possible collapse of the healthcare systems led some countries and healthcare systems to discuss and even adopt an age criterion for the allocation of the scarce health resources, prioritizing the treatment of younger patients (Cesari & Proietti, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020). Alongside these devaluing discourses and practices, a patronizing aspect of ageism emerged too. Many countries advocated the imposition or suggested without imposition stricter restrictions on the older population only, identifying age‐based lockdown as a better strategy than a generalized lockdown on the entire population (Ayalon, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020).

Thus, in multiple ways, public as well as political discourses and practices have encouraged people to believe that COVID‐19 mostly affects the older population whose life is supposed to be less valuable. On the one hand, this spread of ageism contributes to social resistance in adopting health recommendations (e.g., social distancing; American participants in Graf & Carney, 2021) with younger people believing to be COVID‐19 immune and even engaging in dangerous practices such as “Corona parties” as to purposefully infect oneself (Ayalon, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020). On the other hand, it exacerbates the intergenerational tensions among different age groups (Ayalon et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021).

In the light of the above, it is reasonable that the COVID‐19 pandemic can increase the perceived realistic and symbolic threats, fostering competition over the scarce resources. In this specific case, symbolic threat clearly emerges on social media where younger people exhibit anger and outrage against the older ones as a result of some older persons not adhering to anti‐COVID measures (e.g., social isolation; Ayalon, 2020; Silva et al., 2021). Realistic threat, instead, emerges in the support for the adoption of age‐based criteria in both allocating the medical treatments and implementing social isolation measures (Ayalon, 2020). Symbolic and realistic threat, thus, strengthen the idea that older people have already lived their lives and that they have to step aside without stealing younger people's resources, freedom, and lives. Indeed, several authors suggested that this mechanism fosters the division and the conflict between older and younger generations within the society (e.g., Ayalon, 2020; Silva et al., 2021).

However, alongside explanation of ageism during the COVID‐19 pandemic as the result of specific threats, another explanation suggests that during societal crises, unspecific threat can lead to prejudice through attributional processes. Indeed, attributional processes are daily and intuitively applied by people in the attempt to causally explain events (Heider, 1958). Assigning responsibility and/or blame to social actors serves to reduce uncertainty, perceive a sense of control over the events, support individual ideologies, and maintain a positive self and group image (Becker et al., 2011; Penone & Spaccatini, 2019). On the other hand, however, research demonstrated that in several domains, from gender violence to perception of immigration, attributional processes can become a tool for legitimizing prejudice and discrimination (e.g., Becker et al., 2011; Penone & Spaccatini, 2019). Intergroup tension may be especially high during societal crises like financial crises or pandemics, according to research linking attributional processes to perceived threat. Such situations are the result of complex dynamics and evoke an unspecified threat that can, in turn, translate into hostility, prejudice, and discrimination towards specific outgroups throughout group‐level attribution processes. In particular, people cope with the unspecific threat by seeking social groups who can be made responsible for the crisis or the emergence (Allport, 1954; Becker et al., 2011; Glick, 2002; Pacilli et al., 2022; Tajfel, 1969). The choice of the outgroup to be considered responsible for the situation is not fortuitous; instead, it depends on the salient and shared stereotypes within a particular social context (Butz & Yogeeswaran, 2011; Glick, 2002). For instance, research on ethnic prejudice demonstrated that the 2008 financial crisis did not intensify prejudice in general, but only prejudice towards groups who were considered responsible and blameworthy for the severity of the situation, such as immigrant and Jewish populations (Becker et al., 2011).

At the light of this, the intergroup attributional processes can be a root for ageism and age‐based discrimination during pandemic too. However, to our knowledge, most part of the research have been focused on the analysis of the spread of ageism during pandemic and its effects on people's adherence to COVID‐19 control and preventive measures (e.g., Graf & Carney, 2021; Italian participants in Visintin, 2021), leaving the intergroup level under‐investigated.

THE PRESENT RESEARCH

The purpose of the present correlational research was to deepen the knowledge on ageism towards older people during pandemic at an intergroup level. In particular, we aimed at investigating the effects of younger people's endorsement of ageism towards older people on the attitude towards the possible adoption of COVID‐19 restriction measures and prescriptions primarily targeted to older (vs. younger) population.

Our hypotheses are rooted in the broad sociopsychological research literature on intergroup relationship and conflict above mentioned.

In particular, linking the literature on attributional processes and prejudice to the one on ageism during pandemic, we hypothesized that the endorsement of ageism towards older (vs. younger) people would positively correlate with the attribution of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to older (vs. younger) people (H1). Furthermore, we expected a positive relationship between the older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures, the attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation, and support for selective lockdown on older population only (H2). Finally, we hypothesized that the relationship between the endorsement of ageism towards older people and the attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation and support for selective lockdown on older population only would be mediated by the attribution of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to older (vs. younger) people (H3).

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki. The raw data supporting the findings of this study and materials used to collect data are available upon request to the authors.

The research context

The present research was conducted in Italy, one of the European countries with the largest portion of older population (i.e., people over 65 years old). In particular, in Italy the older population represents the 23% of the entire population with a continuous growth in the percentage of older persons in the country (ISTAT, 2020, 2021). However, older individuals constitute a cornerstone for the Italian society thanks to their social, economic, and cultural roles (Petretto & Pili, 2020). Furthermore, a large part of older population acts and lives autonomously, looks younger, and is in good general health (Petretto & Pili, 2020).

As far as the COVID‐pandemic is concerned, Italy was the first European nation hit by the virus and among the most affected countries in the world (Cesari & Proietti, 2020). Furthermore, Italy was the first European country to adopt restrictive measures, with the government imposing the lockdown to the entire country few weeks after the first case diagnosed in mid‐February 2020 (Delmastro & Zamariola, 2020). However, the infection and death rates have increased, challenging the public health system severely. Italian population profoundly changed their habits and lifestyle, and was hardly impacted by the pandemic on a personal, social, psychological, and economic level (Delmastro & Zamariola, 2020; Marazziti et al., 2020), with the health care practitioners, disabled persons, caregivers, and older sick patients experiencing negative consequence more severely (Marazziti et al., 2020). With a focus on older adults, Italy was among the countries that, facing the possibility of healthcare system collapse, discussed and even adopted an age criterion for the allocation of the scarce health resources, prioritizing the treatment of younger patients (Cesari & Proietti, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020).

During COVID‐19 outbreak, the Italian media represented older individuals in a variety of ways (Petretto & Pili, 2020; Previtali et al., 2020). On the one hand, the positive representations of older population showed their efforts to be helpful to the community, for instance, by coming back to work even if retired (e.g., researchers and health care practitioners), while on the other hand, media emphasized older people's frailty and their higher risk of infection and death.

Data were collected in the autumn of 2020 from late November to mid‐December, when alongside an exponential growth of infections (for the data on the infection and death rate in Italy see Corriere della Sera, 2020) that determined an increase in the severity of the COVID‐19 restriction measures (for a description of the Italian prevention and response to COVID‐19 see, Ministero della Salute ‐ Istituto Superiore di Sanità, 2020) and approaching the start of the vaccination campaign (27th of December 2020), some politics (e.g., the aforementioned Giovanni Toti on the 2nd of November 2020) publicly expressed their support for age‐based restrictions on older population, making salient boundaries among age groups and igniting a heated debate among citizens.

Design and participants

Five hundred and eighty‐two participants (83.3% females; M age = 20.02, SD age = 2.83) were recruited through a snowball sampling and voluntarily participated in the study. The research was advertised during university classes by the first and the last authors, who asked students to take part in the study and to spread the link to the online questionnaire to other same‐age persons. The study took about 10 min to be completed and participants did not receive compensation for taking part in the study.

Most of the participants (91.1%) declared to be student and 7.7% to be student worker.

Given that most of our measures were ad hoc developed for the present study and that there was no previous research on the topic, we could not compute a priori power analysis based on previous literature data. However, we ran a power analysis based on correlation among involved variables to test whether our final sample was sufficient to detect the key hypothesized effects in our mediational models, adopting Schoemann et al. (2017) approach. The power for the mediational model with the importance of age‐based self‐isolation behavior as the dependent variable was equal to .79, the power for the mediational model with the support for the imposition of age‐based self‐isolation measures as the dependent variable was equal to .72, and the power for the mediational model with the support for selective lockdown involving only the older population as the dependent variable was equal to .71. Thus, being below the threshold of .80, our models emerged to be slightly underpowered.

Procedure and materials

After providing their consent to participate in the study, participants completed an online questionnaire via the SurveyMonkey platform. The variables were measured in the following order using 7‐point scales ranging from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree), except for ageism scales that were administered using 7‐point semantic differentials. In answering to the questionnaire, participants were asked to think to younger people (i.e., people of their same age) and to older people (i.e., retired people).

Ageism

To assess ageism towards both younger and older people, participants were asked to answer to two different sets of semantic differentials composed by eight pairs of bipolar adjectives each previously used by Rudman et al. (1999; e.g., “close‐minded/open‐minded” and “frail/healthy”; ageism towards older people: Cronbach's α = .60; ageism towards younger people: Cronbach's α = .64). A relative index was calculated by subtracting from ageism towards older people the ageism towards younger people. Higher values indicated greater ageism towards older (vs. younger) people.

Older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures

Participants were presented with the four items reported in Table 1 that assessed the degree to which they considered the cause for the severity of restriction measures to be older populations’ fragility (two items; r = .84, p < .001) and younger people's reckless behavior (two items; r = .79, p < .001). A relative index was calculated by subtracting from culpability of older people score the culpability of younger people. Higher values indicated greater assignment of culpability to older (vs. younger) people.

TABLE 1.

Items ad hoc developed to assess the attribution of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to older (vs. younger) people

| The severity of the measures that the Italian government has adopted since October 2020 to contain the pandemic was caused by : |

|---|

| The need to protect the health of the older people above all. |

| The need to protect the health of the frail people, especially the elderly. |

| The superficial way in which the young people have continued to behave in the last period. |

| The superficial way in which the young people spent the summer (clubs, friends, travel). |

Attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation

We measured the support for a set of isolation measures and prescriptions towards both younger and older populations (See Table 2 for the list of items). Four items assessed the importance of age‐based self‐isolation, asking participants to what extent they considered to be important during pandemic that respectively younger (two items; r = .78, p < .001) and older (two items; r = .79, p < .001) people self‐isolate and not meet other people. Four items assessed the support for imposition of age‐based isolation, asking participants to what extent they support the imposition of measures that prohibit meeting other people indoor as well as outdoor for both younger (two items; r = .61, p < .001) and older (two items; r = .52, p < .001) people. A relative index was calculated for each of the two measures by computing the difference between the index on measures on younger people and the index on measures on older people. Higher values indicated more favorable attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation.

TABLE 2.

Items ad hoc developed to assess attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation

| Importance of age‐based self‐isolation |

|---|

|

To effectively contain the pandemic, it is important that : Older people avoid going out and going around infecting and getting infected. Older people avoid gathering in groups with friends by infecting and getting infected. Young people avoid going out and going around infecting and getting infected. Young people avoid gathering in groups with friends by infecting and getting infected. |

| Support for imposition of age‐based isolation |

|

Please indicate how much you agree with the adoption of the following measures : To obligate the older people to not leave their home. To obligate the older people to not meet non‐cohabiting people at home. To obligate younger people to not meet other people in public spaces (e.g., park). To obligate the younger people to not meet non‐cohabiting people at home. |

| Support for selective lockdown on older population |

|

Please mark the degree to which you agree with the following statements : Between a lockdown on the entire population and a selective one involving the older people only, I'd rather prefer a selective lockdown involving only the older population. If the covid‐19 is dangerous especially for elderly people, it is right that they stay at home in isolation. The adoption of a selective lockdown involving only the elderly population does not mean segregating older people but allowing the productive system to continue its work activity. I think it is wrong asking young people to sacrifice their social life staying at home when it would be enough to isolate the elderly people. |

Support for selective lockdown on older population

In the last part of the questionnaire, four items were developed to capture participants’ support for selective lockdown involving the older population only (See Table 2; Cronbach's α = .83). The index was calculated by averaging participants’ answers to each item.

ANALYSIS PLAN

In an exploratory manner, we ran t‐tests on the study variables to test whether gender differences subsist or not. After that, to test our hypotheses we ran respectively correlations among variable and mediational models. In particular, we ran a mediation analysis because it is a statistical method used to investigate the mechanism at work (i.e., the mediator variable that is the older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures index) that leads the independent variable (i.e., the ageism index) to affect each of our dependent variables (i.e., attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation and support for selective lockdown on older population). The simple mediation model is composed by two consequent variables (the mediator and the dependent variable) and two antecedent variables (the independent variable and the mediator) that causally affect the dependent variable. In particular, the causal effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable is called direct effect, while the causal effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable through the mediator is called indirect effect (Hayes, 2018).

RESULTS

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics for the study variables and the bivariate correlations between them.

TABLE 3.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among variables

| Variables | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ageism | 1.03 | 1.06 | 1 | ||||

| 2. Older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures | 1.10 | 2.26 | .11* | 1 | |||

| 3. Importance of age‐based self‐isolation | .49 | 1.18 | .07 | .22*** | 1 | ||

| 4. Support for imposition of age‐based isolation | .13 | 1.36 | .04 | .15*** | .53*** | 1 | |

| 5. Support for selective lockdown on older population | 2.76 | 1.40 | .11** | .15*** | .42*** | .43*** |

Note: Higher values indicated more negative attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people for ageism, older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures, importance of age‐based self‐isolation, and support for imposition of age‐based isolation.

*p < .05; **p < .01; and ***p < .001.

At an exploratory level, we ran t‐tests introducing participants’ gender as independent variable and our crucial variables as dependent variables. The t‐test conducted on the index of ageism on the older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures did not reveal significant gender differences respectively, t(578) = ‐.60, p =.496 and t(578) = .80, p = .422. Participants’ gender did not significantly impact both the indexes of importance of age‐based self‐isolation, t(578) = .20, p = .578, and support for imposition of age‐based isolation, t(578) = ‐.02, p = .981. Instead, the support for selective lockdown on older population changed according to participants’ gender, t(578) = 2.01, p = .045, with male participants (M = 3.02, SD = 1.33) expressing more support for selective lockdown on the older population only than female participants (M = 2.71, SD = 1.41).

As far as correlations are concerned, as expected (H1), participants’ ageism proved to be positively related with older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of restriction measures. Importantly for the aim of the present research, the analysis showed a significant positive correlation between from one hand the culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures and from the other hand the importance of age‐based self‐isolation, the support for imposition of age‐based isolation and the support for selective lockdown on older population (H2).

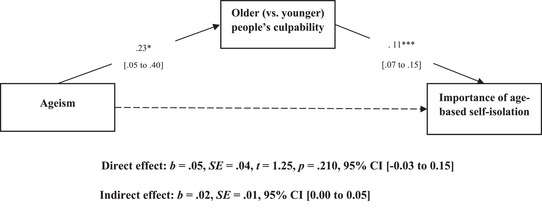

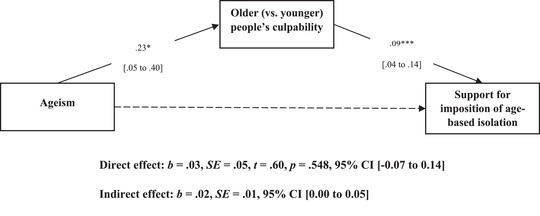

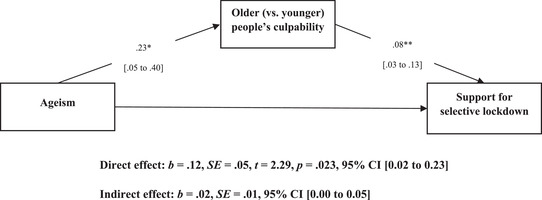

Therefore, to test our main hypothesis (H3), we computed a mediation model on each dependent variable using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018; model 4, 1000 bootstrap resampling). The models comprised the ageism as the independent variable, the culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures as the mediator, and the two indexes of the attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation and the index of the support for selective lockdown on older population as dependent variables (See Figures 1, 2, and 3). All the three models proved to be significant. Ageism significantly predicted the older (vs. younger) people's culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures, b = .23, SE = .09, t = 2.57, p = .010, 95% CI [.05 –.40], in such a way that higher ageism towards older (vs. younger) people led to consider the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to be caused by older people's fragility (vs. younger people's reckless behavior). This variable, in turn, significantly and positively impacted the three dependent variables. As for the importance of age‐based self‐isolation, the effect of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures was significant, b = .11, SE = .02, t = 5.15, p < .001, 95% CI [.07 –.15]. In particular, when higher culpability for the severity of the restriction measures was attributed to the older people's fragility (vs. younger people's reckless behavior), people considered more important that older (vs. younger) people self‐isolate. As for the mediational model on the support for imposition of age‐based self‐isolation, culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures significantly affected the dependent variable, in such a way that when higher culpability for the severity of the COVID‐19 restriction measures was attributed to the older people's fragility (vs. younger people's reckless behavior), people expressed more support for imposition of isolation to older (vs. younger) people, b = .09, SE = .02, t = 3.66, p < .001, 95% CI [.04 –.14]. As for the third model, the effect of the mediator on the dependent variable was significant, indicating that when higher culpability for the severity of the COVID‐19 restriction measures was attributed to the older people's fragility (vs. younger people's reckless behavior), people expressed more support for a selective lockdown targeted to the older population only, b = .08, SE = .03, t = 3.31, p = .001, 95% CI [.03 – .13]. While for all the three models the indirect effect emerged as significant, the direct effect was non‐significant for the models on respectively importance of aged‐based self‐isolation (see Figure 1) and support for imposition of age‐based isolation (see Figure 2), and it was significant for the model on the support for selective lockdown involving the older population only (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 1.

The effect of ageism on the importance of age‐based self‐isolation through the attribution of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to older (vs. younger) people. Higher values indicate more negative attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

FIGURE 2.

The effect of ageism on the support for imposition of age‐based isolation through the attribution of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to older (vs. younger) people. Higher values indicate more negative attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

FIGURE 3.

The effect of ageism on the support for selective lockdown through the attribution of culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures to older (vs. younger) people. Higher values indicate more negative attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

GENERAL DISCUSSION

The current COVID‐19 pandemic has raised numerous challenges in almost all the domain of our lives. At a societal level, COVID‐19 pandemic has turned out to be a hotbed for prejudice and discrimination towards older people (e.g., Silva et al., 2021). The concerns raised by such a situation have driven academics to investigate different aspects of ageism towards older people during pandemic (e.g., Fraser et al., 2020; Graf & Carney, 2021; Ng et al., 2021; Visintin, 2021). Focusing mostly on intrapersonal (e.g., the effects of ageism on older adults’ health conditions and self‐esteem) and interpersonal (e.g., the use of baby talk in the interaction with older adults) level of analysis (for reviews, see, Raina & Balodi, 2014, North & Fiske, 2012), the line of research on ageism has left widely unexplored the intergroup level of ageism (for recent exceptions see, Kanik et al., 2022; Sutter et al., 2022). With the purpose of starting to fill this gap, the aim of the present research was to investigate the effects of younger people's endorsement of ageism towards older people on the attitude towards the adoption of COVID‐19 restriction measures and prescriptions primarily targeted to older (vs. younger) population.

First, the exploration of gender differences on our key variables revealed a significant effect only on the support for selective lockdown targeted to older population, with male participants supporting more this measure than female participants. A first explanation for this result lies in the Social Role Theory (Eagly, 1987) according to which women hold lower level of prejudice and more favorable beliefs about older people due to the fact that women are stereotypically more emphatic and oriented to the care and social others. Our result is also in line with research showing gender differences in attitudes towards older people (Cherry et al., 2016; Rupp et al., 2005). Furthermore, probably the effect emerged on this variable because it was the only one referring to older population exclusively, without comparison with younger population. Thus, it might be possible that for the other variables the saliency of the age‐based social identity has made the boundaries between gender groups and their stereotypes less accessible to respondents. It is, however, worth to note that our sample was unbalanced according to participants’ gender, thus future research should deepen this aspect with a properly balanced sample.

Albeit the correlations among our study variables were quite small, as expected our results revealed positive and significant correlations between ageism and the culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restriction measures and among this latter variable and the measures of attitudes towards older (vs. younger) people isolation and support for selective lockdown on older population. More importantly, the results confirmed our hypotheses according to which greater ageism towards older (vs. younger) individuals would increase the perceived importance and the support towards age‐based COVID‐19 isolation measures involving older (vs. younger) populations and selective lockdown because older (vs. younger) people are perceived as responsible for the severity of the already adopted COVID‐19 restriction measures. It is well‐established that when the resources are scarce, intergroup tensions might be particularly strong, strengthening prejudice and discrimination towards the outgroup(s) (e.g., Becker et al., 2011; Glick, 2002; Schlueter & Davidov, 2013; Stephan & Stephan, 2017). Within this literature, the research by Becker et al. (2011) is of particular relevance to our results. According to the authors in time of complex social crisis, the unspecified sense of threat evoked by the situation is likely to exacerbate intergroup tension if the social context provides stereotypes that facilitate the attribution of responsibility for what is happening to certain well‐identified and stigmatized groups. Accordingly, the authors demonstrated that the 2008 financial crisis intensified prejudice only towards those groups considered as responsible for the severity of the situation, such as immigrant and Jew population (Becker et al., 2011). In a similar vein, COVID‐19 pandemic as the most significant public health issues in the last century has likely evoked an unspecified threat. To deal with such a complexity and uncertainty, people might have made causal attributions about the responsibility of the severity of the restrictions. Furthermore, the group‐level attributions might have been facilitated by media and public discourses, which, at the time of the research ideation and data collection, highly emphasized negative stereotypes about older population, such as their fragility and uselessness, leading to consider the possible adoption of age‐based restrictions (e.g., Ayalon, 2020; Fraser et al., 2020; Ng et al., 2021). These representations might have made boundaries among age groups and social identity particularly salient and, thus, might have facilitate the attribution of responsibility for the situation to older population. The beliefs that the culpability for the severity of the COVID‐19 restriction measures lies on older people, in turn, resulted in increased prejudice, in the form of support age‐based restrictions targeted to older population only. Our results are in line with the research literature on the prescriptive approach to ageism too (North & Fiske, 2013). According to this approach, the strongest intergenerational conflict is the one between younger and older people, because they are both lower status groups as compared to adult population (North & Fiske, 2013). In general, younger people tend to believe that their success and access to resources largely depend upon older people's behaviors and their withdrawal from resources access (North & Fiske, 2013). Therefore, younger people exhibit greater hostility towards older people who do not follow prescriptions about how older people should be, especially in three main domains: Succession, Identity, and Consumption (SIC; North & Fiske, 2013). Thus, according to prescriptive stereotypes older people should have to step aside in order to not limit younger people's opportunities (Succession), should “act their age” avoiding cross the boundaries between age‐groups to look younger (Identity), and stopping being passive consumers of societal shared resources at younger population disadvantages (Consumption). Albeit our research has not been conducted to test this model, the results of our mediational models is consistent at least with the prescriptive dimensions of Succession and Consumption. Indeed, the supportive attitudes towards social isolation of older people might be seen as an expression that older individuals have to stepping aside to not limit younger's freedom during pandemic and have to stop consuming resources (such as health system resources) by infecting themselves because they are frail and susceptible of severe form of COVID‐19.

Limits and future directions

There are also some limitations to the present study. On the methodological side, the two major limitations pertain the low reliability of our ageism measure and our sample size. As for the sample size, despite we enrolled as much participants as possible, our study emerged to be slightly underpowered. The quite low alphas of the ageism scales might have attenuated the observed results. Future research, thus, should be conducted to replicate and extend our results considering both a more reliable measure of ageism and a sample of adequate size.

On the results side, the mediational model conducted with support for selective lockdown involving the older population only as dependent variable emerged to be a partial mediation, with both direct and indirect effects emerged to be significant. This result might be due to the different level to which the variables considered in the model was referring to. Specifically, while ageism and culpability for the severity of COVID‐19 restrictions were computed comparing attitudes towards younger and older people, the support for selective lockdown was assessed referring to older population exclusively. Thus, the partial mediation effect might be due to the fact that the dependent variable did not compare attitudes towards selective lockdown towards older versus younger population. We assessed the support for selective lockdown on older population because it was a discussed theme within the public debate about alternatives to avoid a lockdown to the entire population at the moment of research ideation and data collection. However, this aspect constitutes a significant limit of our research that future study should overcome. Additionally, the partial mediation might indicate that there are other variables, that we did not consider, able to mediate the relationship between ageism and the dependent variable. However, given that this mediational model emerged to be slightly underpowered, our interpretation should be considered cautiously posing the need to run more studies to better disambiguate the direct and indirect relationship between ageism and supportive attitude towards selective lockdown on older population, relying on adequate sample and exploring for the sequential mediation of other variables.

At the light of the general paucity of research on ageism during pandemic at an intergroup level, we focused our attention on the attitudes of younger people towards older people in general. However, an additional aspect that merits greater attention is the effects of intersection of different socio‐demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, ethnicity, income, and disabilities; e.g., Rueda, 2021). Indeed, while it is widely demonstrated how each form of discrimination can impair individuals’ psychophysical health and that multiple stigmatized group memberships could result in health care injustice (e.g., Chrisler et al., 2016; Nash et al., 2020; Rueda, 2021), the consequences of intersectional prejudice and discrimination based on social identities other than age still remain an under‐studied topic. From the scant literature about intersectionality, it emerged that COVID‐19 has amplified existing inequalities and discrimination, impacting differently on individuals according to their belonging to multiple social groups (Cox, 2020; Gutterman, 2021; Maestripieri, 2021). For instance, the likelihood of getting infected and of other health‐related risks is increased when age intersect with ethnicity and income. Indeed, older African American individuals as well as older individuals with lower income were more susceptible to infection and to be discriminated by the health care system (Cox, 2020; Gutterman, 2021).

Thus, stemming from our result, future studies should be conducted to investigate whether ageism and other forms of prejudice jointly affect group‐level attribution of culpability and support for social exclusion practices such as selective lockdown.

We focused our attention on the ageism towards older people. However, literature clearly demonstrated that they are not the only age group vulnerable to ageism. Indeed, younger population are susceptible of prejudice and discrimination based on age too, with this form of ageism potentially contributing to intergenerational tension and conflict (Swift & Chasteen, 2021). For instance, adult and older individuals might attribute the culpability for the severity of the COVID‐19 restriction measures to younger individuals because of their reckless behaviors during the summer holiday. Thus, to build a more holistic approach to the investigation to ageism during and beyond the pandemic, future studies should investigate the ageism towards younger population at an intergroup level.

Practical implications

Although more research is needed on the topic, our results hold important academic and practical implications. From an academic perspective, our research extends previous research literature on ageism towards older people providing first evidence on its effects during pandemic at an intergroup level. In particular, our results revealed that younger people's endorsement of ageism towards older (vs. younger) people is associated with group level attribution, with older people being considered responsible for the severity of the COVID‐19 restriction measures imposed to the general population due to their fragility. Such an attribution, in turn, is in relationship with discrimination and social exclusion in the form of isolation measures targeted primarily to older population. Our results also contribute to extend the knowledge of intergenerational relationship over and beyond the pandemic. Alongside explanation of ageism as the result of specific threats, our findings indicate that intergenerational tension might take the shape of attribution of culpability, which can be among the possible mechanisms that legitimize prejudice and discrimination.

Practically speaking, our results provided useful insights for both social policies and public discourses. Research literature demonstrated older people's psychophysical wellbeing is impaired by experiencing both ageism and prolonged social isolation (e.g., Cohn‐Schwartz et al., 2022; Plagg et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021) and that ageism towards older people affects people adherence to COVID‐19 preventive measures (e.g., Graf & Carney, 2021; Visintin, 2021). Our results show that an intergroup level ageism towards older people is indirectly associated with the support for age‐based isolation and suggest that, the growing ageism and is associated with division between generations, resentment, and blame attribution to older people. Thus, social policies and various stakeholders should focus their efforts in contrasting ageism as to contain age‐based discrimination. In this regard, it is first important that social policies, media, and politics become aware of the negative potential of stereotyped discourses about aging and age groups and, thus, develop a code of conduct to avoid reinforcing prejudice.

In this regard, there are several examples of codes of conduct promoting positive social change. In 2015, in the Italian context, for instance, the municipality of Pordenone developed a code of conduct to challenge gender stereotypes in media representations. The document was signed by numerous social actors (e.g., institutions, municipalities, and associations) and the number of signatories is still growing (Comune di Pordenone, 2015). Furthermore, it stimulated projects and interventions, and it was cited by the 2019 report of the GREVIO (i.e., an independent expert body on gender violence of the Council of Europe) as an example of good social practice to contrast prejudice.

Then, these social actors (e.g., institutions, municipalities, associations, and journalists) should in turn address their efforts to reduce ageism during and beyond the pandemic to ameliorate intergroup relationship and psychophysical health of the general population. One possible strategy might be to avoid stereotyped representations of older population as a homogeneous group composed by frail and impaired individuals recognizing the heterogeneity and diversity of older adults (e.g., Ayalon & Okun, 2022). Instead, representations of older adults should emphasize how they contribute in helping society during pandemic (e.g., retired people who came back to work) and, in general, how important their roles are socially, culturally and economically (for recent research on representation of older adults as contributors during COVID‐19 pandemic see, Lytle & Levy, 2022). It should be equally important to avoid relying on age as the unique and most important factor in predicting COVID‐19 susceptibility, allocation of medical treatments and, for the implementation of COVID‐19 measures. Indeed, public policies should develop criterion and parameters more robust and less discriminant than age (Cesari & Proietti, 2020). Another strategy is to promote solidarity among different generations. In this regard, research has provided abundant evidence that interventions based on education as well as contact between different age groups are effective in reducing ageist attitudes and behaviors (Burnes et al., 2019; Drury et al., 2022). In this regard, it should be also important to emphasize in media and public discourses the social value of the numerous episodes of intergenerational solidarity emerged during the pandemic, with younger people helping older ones in doing the grocery shopping and maintaining social connections with others (Ayalon et al., 2020; Silva et al., 2021). Additionally, policy makers should collaborate with communities as to develop public policies for the “reconstruction” after the COVID‐19 pandemic that recognize the importance of older segment of society and assign them new and helpful roles in the process of reconstruction (Petretto & Pili, 2020).

Thus, it emerged of primary relevance to avoid that physical distancing become emotional distancing, to promote the norms of solidarity and cooperation, and to encourage the consideration of people as human beings regardless of their age.

CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This work was not supported by any grant.

Biographies

Federica Spaccatini is a post‐doc fellow in Social Psychology at the University of Milano‐Bicocca in Italy. She completed her PhD in Human Sciences (specialization in Social Psychology) at the University of Perugia, Italy. Her main research interests lie in the field of social psychology with a particular focus on prejudices and discriminations, dehumanization, sexualization and sexual objectification, victim blaming, and Human‐Technology Interactions.

Ilaria Giovannelli is a post‐doc fellow in Social Psychology at the University of Perugia in Italy. She earned her PhD student in Politics, Public Policies, and Globalization (specialization in Social Psychology). Her research interests are in social and health psychology and, specifically, health promotion in educational contexts, abortion stigma, reproductive health and rights, and dehumanization.

Maria Giuseppina Pacilli is Associate Professor of Social Psychology at the University of Perugia where she teaches Social Psychology (undergraduate level) and Digital Media Psychology (graduate level). She is dean of the BA Course in Social Work and MA Course in Politics and Social Services (since 2019) and co‐director of the departmental IDG (Intersezioni di Genere)‐Research Group on gender studies (since 2014). Dr Pacilli's main research activities focus on core themes of social psychology, such as gender discrimination and violence (effects of appearance and sexism on social perception, intimate partner violence) and intragroup regulation processes (social influence, ethical behavior in the organizations).

Spaccatini, F. , Giovannelli, I. & Pacilli, M.G. (2022) “You are stealing our present”: Younger people's ageism towards older people predicts attitude towards age‐based COVID‐19 restriction measures. Journal of Social Issues, 00, 1–21. 10.1111/josi.12537

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The raw data supporting the findings of this study and materials used to collect data are available upon request to the authors.

REFERENCES

- Abrams, D. , Swift, H.J. & Drury, L. (2016) Old and unemployable? How age‐based stereotypes affect willingness to hire job candidates. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 105–121, 10.1111/josi.12158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allport, G.W. (1954) The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison‐Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- ANSA. (2020) Toti suggests limitations on elderly to avert lockdown. Retrieved from: https://www.ansa.it/english/news/politics/2020/11/02/toti‐suggests‐limitations‐on‐elderly‐to‐avert‐lockdown_a642c646‐b741‐4b87‐bd29‐203e27f49556.html

- Ayalon, L. (2020) There is nothing new under the sun: ageism and intergenerational tension in the age of the COVID‐19 outbreak. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(10), 1221–1224. 10.1017/S1041610220000575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. , Chasteen, A. , Diehl, M. , Levy, B. , Neupert, S.D. , Rothermund, K. , Tesch‐Romer, C. & Wahl, H.W. (2020) Aging in times of the COVID‐19 pandemic: avoiding ageism and fostering intergenerational solidarity. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(2), e49–e52. 10.1093/geronb/gbaa051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayalon, L. & Okun, S. (2022) Eradicating ageism through social campaigns: an Israeli case study in the shadow of the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Social Issues. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, J. C. , Wagner, U. & Christ, O. (2011) Consequences of the 2008 financial crisis for intergroup relations: the role of perceived threat and causal attributions. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14(6), 871–885. doi: 10.1177/1368430211407643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Becket, L. (2020) Older people would rather die than let Covid‐19 harm US economy – Texas official. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/24/older‐people‐would‐rather‐die‐than‐let‐covid‐19‐lockdown‐harm‐us‐economy‐texas‐official‐dan‐patrick [Google Scholar]

- Brooke, J. & Jackson, D. (2020) Older people and COVID‐19: isolation, risk and ageism. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13‐14), 2044–6. 10.1111/jocn.15274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnes, D. , Sheppard, C. , Henderson Jr, C.R. , Wassel, M. , Cope, R. , Barber, C. & Pillemer, K. (2019) Interventions to reduce ageism against older adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 109(8), e1–e9. 10.2105/ajph.2019.305123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler, R.N. (1969) Age‐ism: another form of bigotry. The Gerontologist, 9(4), 243–246. 10.1093/geront/9.4_Part_1.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butz, D.A. & Yogeeswaran, K. (2011) Another threat in the air: macroeconomic threat increases prejudice against Asian Americans. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 22–27. 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.07.014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cesari, M. & Proietti, M. (2020) COVID‐19 in Italy: ageism and decision making in a pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(5), 576–577. 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.03.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang, E.S. , Kannoth, S. , Levy, S. , Wang, S.Y. , Lee, J.E. & Levy, B.R. (2020) Global reach of ageism on older persons’ health: a systematic review. Plos One, 15(1), e0220857. 10.1371/journal.pone.0220857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, K.E. , Brigman, S. , Lyon, B.A. , Blanchard, B. , Walker, E.J. & Smitherman, E.A. (2016) Self‐reported ageism across the lifespan: role of aging knowledge. The International Journal of Aging, 83(4), 366–380. 10.1177/0091415016657562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chrisler, J.C. , Barney, A. & Palatino, B. (2016) Ageism can be hazardous to women's health: ageism, sexism, and stereotypes of older women in the healthcare system. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 86–104, 10.1111/josi.12157 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christian, J. , Turner, R. , Holt, N. , Larkin, M. & Cotler, J.H. (2014) Does intergenerational contact reduce ageism: when and how contact interventions actually work? Journal of Arts and Humanities, 3(1), 1–15. 10.18533/journal.v3i1.278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn‐Schwartz, E. , Kobayashi, L.C. & Finlay, J.M. (2022) Perceptions of societal ageism and declines in subjective memory during the COVID‐19 pandemic: longitudinal evidence from US ands aged ≥ 55 years. Journal of Social Issues [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contoli, B. , Carrieri, P. , Masocco, M. , Penna, L. , Perra, A. & Study Group P. D. A. (2016) PASSI d'Argento (Silver Steps): the main features of the new nationwide surveillance system for the ageing Italian population, Italy 2013‐2014. Annali dell'Istituto superiore di sanita, 52(4), 536–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conzo, P. , Fuochi, G. , Anfossi, L. , Spaccatini, F. & Mosso, C.O. (2021) Negative media portrayals of immigrants increase ingroup favoritism and hostile physiological and emotional reactions. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–11. 10.1038/s41598-021-95800-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, C. (2020) Older adults and covid 19: social justice, disparities, and social work practice. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6‐7), 611–624, 10.1080/01634372.2020.1808141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J. & Fiske, S.T. (2002) Doddering, but dear: process, content, and function in stereotyping of elderly people. In: Nelson, T.D. (Ed.) Ageism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Cuddy, A.J.C. , Norton, M.I. & Fiske, S.T. (2005) This old stereotype: the pervasiveness and persistence of the elderly stereotype. Journal of Social Issues, 61, 267–285. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00405.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delmastro, M. & Zamariola, G. (2020) Depressive symptoms in response to COVID‐19 and lockdown: a cross‐sectional study on the Italian population. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–10. 10.1038/s41598-020-79850-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derrer‐Merk, E. , Reyes‐Rodriguez, M. , Salazar, A.M. , Guevara, M. , Rodriguez, G. , Fonseca, A.M. , Camacho, F. , Ferson, S. , Mannis, A. , Bentall, R. & Bennett, K.M. (2022) Is protecting older adults from COVID‐19 ageism? A comparative cross‐cultural constructive grounded theory from the United Kingdom and Colombia. Journal of Social Issues [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drury, L. , Abrams, D. & Swift, H.J. (2022) Intergenerational contact during and beyond COVID‐19. Journal of Social Issue [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagly, A. (1987) Sex differences in social behavior: a social role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Esses, V.M. & Hamilton, L.K. (2021) Xenophobia and anti‐immigrant attitudes in the time of COVID‐19. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 253–259. 10.1177/1368430220983470 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fiske, S.T. , Cuddy, A.J.C. , Glick, P. & Xu, J. (2002) A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser, S. , Lagacé, M. , Bongué, B. , Ndeye, N. , Guyot, J. , Bechard, L. , Garcia, L. , Taler, V. , CCNA Social Inclusion & Stigma Working Group , Adam, S. , Beaulieu, M. , Di Bergeron, C. , Boudjemadi, V. , Desmette, D. , Donizzetti, A. R. , Ethier, S. , Garon, S. , Gillis, M. , Levasseur, M. , Lortie‐Iussier, M. , Marier, P. , Robitaille, A. , Sswchuk, K. , Lafontaine, C. & Tougas, F. (2020) Ageism and COVID‐19: what does our society's response say about us? Age and ageing, 49(5), 692–695. 10.1093/ageing/afaa097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick, P. (2002) Sacrificial lambs dressed in wolves’ clothing: envious prejudice, ideology, and the scapegoating of Jews. In: Newman L.S. & Erber R. (Eds.) Understanding genocide: the social psychology of the Holocaust. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 113–142. [Google Scholar]

- Graf, A.S. & Carney, K.A . (2021) Ageism as a modifying influence on COVID‐19 health beliefs and intention to social distance. Journal of Aging and Health, 33(7‐8), 518–530. 10.1177/2F0898264321997004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg, J. , Helm, P. , Maxfield, M. & Schimel, J. (2017) How our mortal fate contributes to ageism: a terror management perspective. In: Nelson, T.D. (Ed.) Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Boston Review, pp. 105–132. [Google Scholar]

- GREVIO. (2019) Rapporto di Valutazione di Base Italia. Retrieved from: http://www.informareunh.it/wp‐content/uploads/GREVIO‐RapportoValutazioneItalia2020‐ITA.pdf

- Gutterman, A. (2021) Ageism and intersectionality: older persons as members of other vulnerable groups. Older Persons’ Right Project. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3972842 or 10.2139/ssrn.3972842 [DOI]

- Hayes, A.F. (2018) Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression‐based approach, 2nd edition. New York, US: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heider, F. (1958) The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York: Wiley; [Google Scholar]

- Hummert, M.L. , Garstka, T.A. , Shanor, J.L. & Strahm, S. (1994) Stereotypes of the elderly held by young, middle‐aged, and elderly adults. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 49(5), 240–249. 10.1093/geronj/49.5.P240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISTAT . (2020) Lavoro e retribuzioni . Retrieved from: https://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=DCCV_TAXOCCU1#

- ISTAT . (2021) Popolazione e famiglie . Retrieved from: http://dati.istat.it/Index.aspx?QueryId=42869#

- Jelenec, P. & Steffens, M.C. (2002) Implicit attitudes toward elderly women and men. Current Research in Social Psychology, 7(16), 275–293. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez‐Sotomayor, M.R. , Gomez‐Moreno, C. & Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, E. (2020) Coronavirus, ageism, and twitter: an evaluation of tweets about older adults and COVID‐19. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8), 1661–1665. 10.1111/jgs.16508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanik, B. , Uluğ, O.M. , Solak, N. & Chayinska, M. (2022) Why worry? The virus is just going to affect the old folks”: social Darwinism and ageism as barriers to supporting policies to benefit older individuals. Journal of Social Issues. [Google Scholar]

- Kite, M.E. , Stockdale, G.D. , Whitley Jr, B.E. & Johnson, B.T. (2005) Attitudes toward younger and older adults: an updated meta‐analytic review. Journal of social issues, 61(2), 241–266. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00404.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kite, M.E. & Wagner, L.S. (2004) Attitudes toward older adults. In: Nelson, T.D. (Ed.) Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 129–161. [Google Scholar]

- Krings, F. , Sczesny, S. & Kluge, A. (2011) Stereotypical inferences as mediators of age discrimination: the role of competence and warmth. British Journal of Management, 22(2), 187–201. 10.1111/j.1467-8551.2010.00721.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, S.R. & Macdonald, J.L. (2016) Progress on understanding ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 5–25. https://10.1111/josi.12153 [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B. (2009) Stereotype embodiment: a psychosocial approach to aging. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18, 332–336. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01662.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy, B.R. & Banaji, M.R. (2002) Implicit ageism. In: Nelson, T.D. (Ed.) Ageism: stereotyping and prejudice against older persons. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, pp. 49–75. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd‐Sherlock, P. , Guntupalli & Sempe (2022) Age discrimination, the right to life and COVID‐19 vaccination in countries with limited resources. Journal of Social Issue [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, A. & Levy, S.R. (2019) Reducing ageism: education about aging and extended contact with older adults. The Gerontologist, 59(3), 580–588. 10.1093/geront/gnx177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytle, A. & Levy, S.R. (2022) Reducing ageism toward older adults and highlighting older adults as contributors during the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Journal of Social Issue [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri, L. (2021) The Covid‐19 pandemics: why intersectionality matters. Frontiers in Sociology, 6, 642662. 10.3389/fsoc.2021.642662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marazziti, D. , Pozza, A. , Di Giuseppe, M. & Conversano, C. (2020) The psychosocial impact of COVID‐19 pandemic in Italy: a lesson for mental health prevention in the first severely hit European country. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 531–533. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/tra0000687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques, S. , Mariano, J. , Mendonça J., De Tavernier, W. , Hess, M. , Naegele, L. , Peixeiro, F. & Martins, D. (2020) Determinants of ageism against older adults: a systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2560, 1–27. 10.3390/ijerph17072560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucchi Faina, A. (2013) Troppo giovani, troppo vecchi: il pregiudizio sull'età. Gius. Laterza & Figli Spa. [Google Scholar]

- Nash, P. , Taylor, T. & Levy, B. (2020) The intersectionality of ageism. Innovation in Aging, 4(Suppl 1), 846–847. 10.1093/geroni/igaa057.3105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Chow, T.Y.J. & Yang, W. (2021) Culture linked to increasing ageism during Covid‐19: evidence from a 10‐billion‐word corpus across 20 countries. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(9), 1808–1816. 10.1093/geronb/gbab057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, R. , Indran, N. & Liu, L. (2022) Ageism narratives on twitter during COVID‐19. Journal of Social Issues [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng, S.H. (1998) Social psychology in an ageing world: ageism and intergenerational relations. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 1(1), 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- North, M.S. & Fiske, S.T. (2016) Resource scarcity and prescriptive attitudes generate subtle, intergenerational older‐worker exclusion. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 122–145, 10.1111/josi.12159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North, M.S. & Fiske, S.T. (2013) Act your (old) age: prescriptive, ageist biases over succession, identity, and consumption. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 720–734. 10.1177/2F0146167213480043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North, M.S. & Fiske, S.T. (2012) An inconvenienced youth? Ageism and its potential intergenerational roots. Psychological Bulletin, 138(5), 982–997. 10.1037/a0027843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek, B.A. , Banaji, M.R. & Greenwald, A.G. (2002) Harvesting implicit group attitudes and beliefs from a demonstration web site. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6(1), 101–115. 10.1037/1089-2699.6.1.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orimo, H. , Ito, H. , Suzuki, T. , Araki, A. , Hosoi, T. & Sawabe, M. (2006) Reviewing the definition of “elderly. Geriatrics & gerontology international, 6(3), 149–158. 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2006.00341.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pacilli, M. G. , Pagliaro, S. , Bochicchio, V. , Scandurra, C. & Jost, J. T. (2022) Right‐Wing Authoritarianism and Antipathy Toward Immigrants and Sexual Minorities in the Early Days of the Coronavirus Pandemic in Italy. Frontiers in Political Science, 4, 879049. 10.3389/fpos.2022.879049 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Penone, G. & Spaccatini, F. (2019) Attribution of blame to gender violence victims: a literature review of antecedents, consequences, and measures of victim blame. Psicologia Sociale, 2, 133–164. 10.1482/94264 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Petretto, D.R. & Pili, R. (2020) Ageing and COVID‐19: what is the role for elderly people? Geriatrics, 5(2), 25. 10.3390/geriatrics5020025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plagg, B. , Engl, A. , Piccoliori, G. & Eisendle, K. (2020) Prolonged social isolation of the elderly during COVID‐19: between benefit and damage. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 89, 104086. 10.1016/2Fj.archger.2020.104086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pordenone C.d. (2015) Carta di Pordenone «Media e rappresentazione di genere». Retrieved from: https://www.comune.pordenone.it/it/comune/progetti/carta‐di‐pordenone

- Previtali, F. , Allen, L.D. & Varlamova, M. (2020) Not only virus spread: the diffusion of ageism during the outbreak of COVID‐19. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4‐5), 506–514. 10.1080/08959420.2020.1772002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina, D. & Balodi, G. (2014) Ageism and stereotyping of the older adult. Scholars Journal of Applied Medical, 2(2C), 733–739. [Google Scholar]

- Rothermund, K. & Brandtstädter, J. (2003) Age stereotypes and self‐views in later life: evaluating rival assumptions. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27(6), 549–554. 10.1080/2F01650250344000208 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rudman, L.A. , Greenwald, A.G. , Mellott, D.S. & Schwartz, J.L. (1999) Measuring the automatic components of prejudice: flexibility and generality of the Implicit Association Test. Social Cognition, 17(4), 437–465. 10.1521/soco.1999.17.4.437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda, J. (2021) Ageism in the COVID‐19 pandemic: age‐based discrimination in triage decisions and beyond. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, 43, 91. 10.1007/s40656-021-00441-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rupp, D.E. , Vodanovich, S.J. & Credé, M. (2005) The multidimensional nature of ageism: construct validity and group differences. The Journal of social psychology, 145(3), 335–362. 10.3200/SOCP.145.3.335-362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanità M.d.S.‐I.S.d. (2020) Prevention and response to COVID‐19: evolution of strategy and planning in the transition phase or the autumn‐winter season. Retrieved from: https://www.iss.it/documents/5430402/0/COVID+19_+strategy_ISS_MoH+/281/29.pdf/f0d91693‐c7ce‐880b‐e554‐643c049ea0f3?t=1604675600974

- Schlueter, E. & Davidov, E. (2013) Contextual sources of perceived group threat: negative immigration‐related news reports, immigrant group size and their interaction, Spain 1996–2007. European Sociological Review, 29(2), 179–191. 10.1093/esr/jcr054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schoemann, A.M. , Boulton, A.J. & Short, S.D. (2017) Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. 10.1177/2F1948550617715068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sera C.d. (2020) Coronavirus, la mappa del contagio in Italia. Retrieved from: https://www.corriere.it/speciale/salute/2020/mappa‐coronavirus‐italia/

- Sherif, M. , Harvey, O.J. , White, B.J. , Hood, W.R. & Sherif, C.W. (1961) Intergroup conflict and cooperation: the Robbers' Cave experiment. Norman, Okla: University Book Exchange. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, M.F. , Silva, D.S.M.D. , Bacurau, A.G.D.M. , Francisco, P.M.S.B. , Assumpção, D.D. , Neri, A.L. & Borim, F.S.A. (2021) Ageism against older adults in the context of the COVID‐19 pandemic: an integrative review. Revista de Saúde Pública, 55(4). 10.11606/s1518-8787.2021055003082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper, A.D. & Rose, D.J. (2021) # BoomerRemover: COVID‐19, ageism, and the intergenerational twitter response. Journal of Aging Studies, 57, 100929. 10.1016/j.jaging.2021.100929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, A. (2020) Coronavirus: UK over‐70 s to be asked to stay home ‘within weeks’, Hancock says. The Guardian. Retrieved from: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/15/coronavirus‐uk‐over‐70s‐to‐be‐asked‐to‐self‐isolate‐within‐weeks‐hancock‐says [Google Scholar]

- Stephan, W.G. & Stephan, C.W. (2017) Intergroup threat theory. In: Kim, Y.Y. (Ed.) The international encyclopedia of intercultural communication. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, H.J. & Chasteen, A.L. (2021) Ageism in the time of COVID‐19. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(2), 246–252. 10.1177/2F1368430220983452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter, A. , Vaswani, M. , Denice, P. , Choi, K.H. , Bouchard, J. & Esses, V. (2022) Ageism toward older adults during the COVID‐19 pandemic: intergenerational conflict and support. Journal of Social Issues [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel, H. (1969) Cognitive aspects of prejudice. Journal of Social Issues, 25, 79–95. 10.1017/S0021932000023336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Visintin, E.P. (2021) Contact with older people, ageism, and containment behaviours during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 31(3), 314–325. 10.1002/casp.2504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement