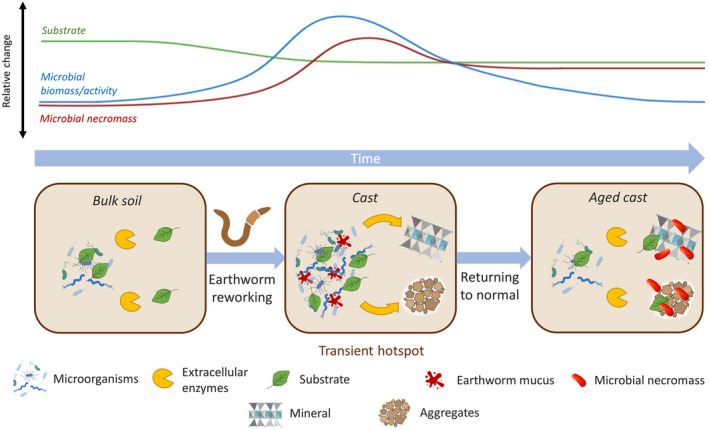

FIGURE 2.

Embracing the central role of earthworms in microbial necromass formation and stabilization. In the initial state, the bulk soil is characterized by a slow formation rate of microbial necromass due to a lack of easily decomposable compounds, a low CUE, and the partial separation of microorganisms and their substrates. Earthworm reworking of this soil co‐locates microorganisms and substrates and provides nutrients and bioavailable compounds in casts. This induces a transient microbial hotspot in which microbial activity and CUE are strongly increased. As a consequence, microbial substrates are partly consumed and microbial biomass quickly and efficiently built‐up, whose necromass is subsequently stabilized in (earthworm‐generated) cast aggregates and by interaction with minerals. With increasing time after casting, microbial biomass, activity, and necromass formation gradually decrease to the initial level, while most of the microbial necromass generated in the transient hotspot is now part of the (stabilized) SOM pool (aged cast). Subsequent reworking of the same soil likely has a smaller effect due to partial re‐synthesis of microbial necromass (Buckeridge, Mason, et al., 2020). The relevance of this concept likely follows a seasonal trend based on the earthworm's life cycle (dormant during cold/hot and dry periods; Gates, 1961) and would be highest for (epi‐)endogeic species, given their abundance, biomass, and specifically, their life strategy (foraging in mineral soil horizons) and temporary burrows, that is, frequent infilling necessitates the continuous reconstruction of burrows (Capowiez, Bottinelli, & Jouquet, 2014; Potvin & Lilleskov, 2017) and higher volumes of affected soil. Factors that influence the stabilization of SOM (Castellano et al., 2015; Li et al., 2022) and the abundance, biomass, and activity of earthworms, such as land use (Figure 1b; Spurgeon et al., 2013), management (e.g., till vs. no‐till; Pelosi et al., 2014; Pérès et al., 2010), ecosystem development (Frouz et al., 2008; Zou & Gonzalez, 1997), climate (Figure 1c; Phillips et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2019), soil group (Figure 1d; Clause et al., 2014), or interaction with other soil fauna (Lubbers et al., 2019), may further modify the relevance of earthworms to the generation and stabilization of microbial necromass