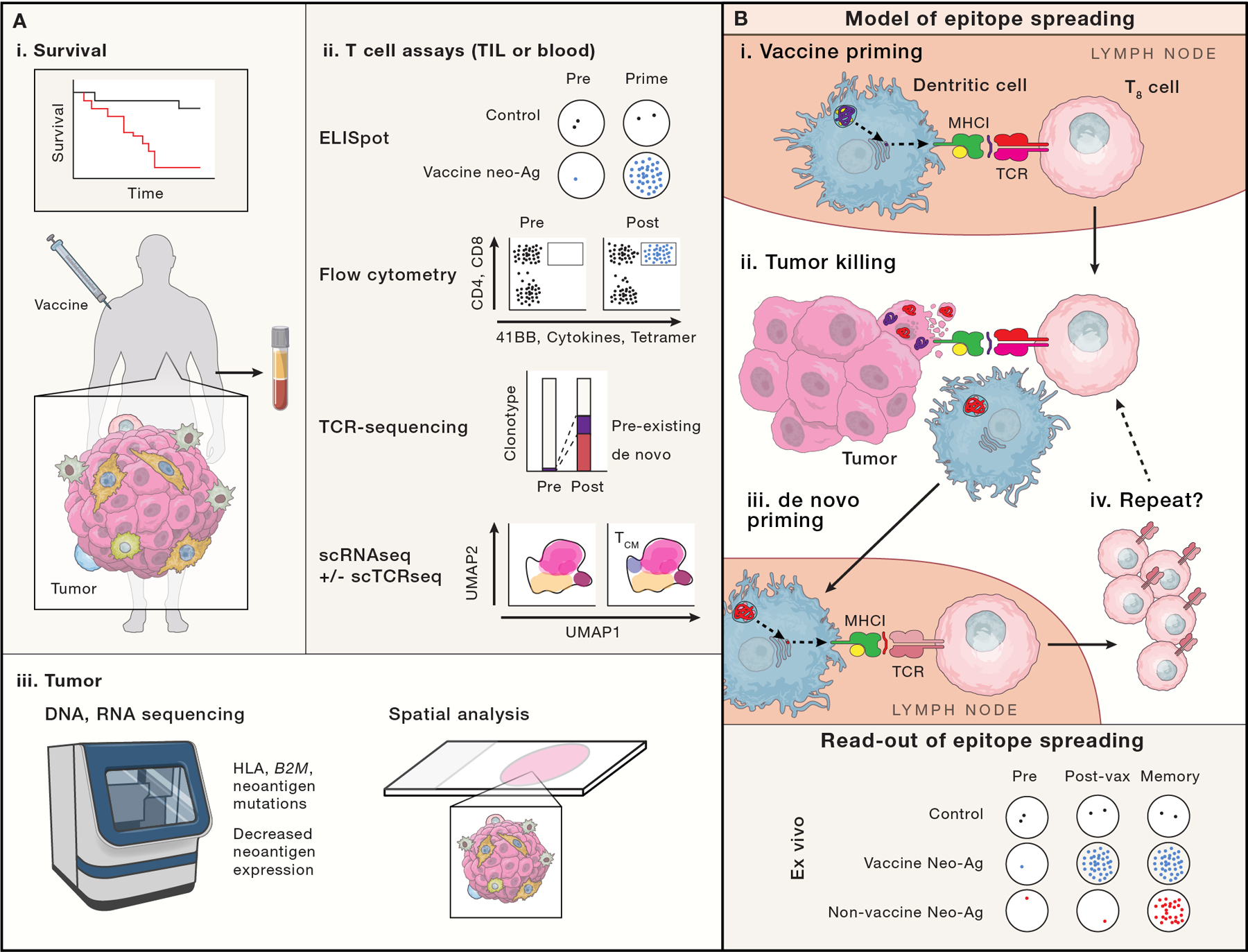

Figure 6: Measuring success.

Ideally a cancer vaccine will demonstrate improved survival or progression free survival (A-i), although cancer vaccine trials are not usually powered to do so. Trials more typically focus on putative correlates of vaccine effectiveness via ex vivo analysis of T cells from the blood or tumor samples (A-ii) or analysis of tumor biopsies (A-iii). (A-ii) T cell assays include: ELISPOT, which enumerates T cell clones responsive to a defined peptide/epitope; flow cytometry based assays, which can identify antigen-specific T cells via p:MHC conjugates (e.g. tetramers), and define T cell function, activation and cytotoxic potential via cytokine, surface 41BB and CD107a exposure; bulk TCR sequencing can temporally track clonotype frequencies; single cell RNA and TCR sequencing (not broadly used in vaccine studies) may enable the linkage of clonotype changes to changes in cell state (e.g. effector, central memory, progenitor exhausted and exhausted). Linking TCR sequence to antigen specificity is not readily possible except through more extensive functional studies. (A-iii) Re-biopsy of tumor can provide evidence of vaccine effectiveness, for example, if genomic or expression analyses demonstrate loss of antigen presenting machinery or neoantigens, or decreased neoantigen expression. Newer spatial multiplexed IHC, in situ hybridization (Nanostring) and sequencing (Slide-seq), may show differences in T cell infiltration patterns (especially when paired with TCR sequencing methods). (B) Schema of epitope spreading. We propose that analysis of epitope spreading may best balance feasibility and sensitivity for vaccine efficacy. Epitope spreading is the concept that one antigen-specific immune response begets another: First, a vaccine primes a CD8+ T cell (purple T8 cell recognizing a purple neoantigen; B-i). That vaccine specific CTL migrates to the tumor (B-ii), where it recognizes and destroys a cancer cell, releasing DAMPs that stimulate a DC maturation and phagocytoses tumor cell remnants, including non-vaccine targeted neoantigens (red). The DC migrates to a draining LN (B-iii), where it presents neoantigens to T cells. A CD8+ T cell (red) with specificity for a new neoantigen is de novo primed and expanded, returning to the tumor (B-iv). B-bottom, model ELISPOT data reflecting epitope spreading is shown, with vaccine induced neoantigen responses appearing after vaccine priming, but non-vaccine neoantigen responses from epitope spreading, appearing only later.