Abstract

Objectives

Previous studies have reported that self-neglect, which may be a sign of elder abuse, can result in suicide among older adults. The signs of self-neglect and its impact on the risk of suicide may differ by gender. Thus, this study explored the association between self-neglect and suicide risk in older Korean adults and examined the potential moderating effect of gender on this relationship.

Methods

Data were collected from 356 Korean adults aged 65 or older through an online survey. Multiple regression analysis was used to test the research hypothesis. First, the associations between 4 sub-dimensions of self-neglect (i.e., daily life management issues, personal hygiene issues, financial management issues, and relational issues) and suicidal ideation were examined. Then, the moderating effect of gender on these relationships was investigated by including interaction terms.

Results

Self-neglect was significantly associated with suicidal ideation in older adults. Aspects of self-neglect related to daily life management and relational factors were key predictors of suicidal ideation. Gender significantly moderated the effect of the relational dimension of self-neglect on suicidal ideation. The relational dimension of self-neglect was more strongly associated with suicidal ideation in older women than in older men.

Conclusions

The findings suggest the importance of screening older adults with signs of self-neglect for suicide risk. Special attention should be paid to older women who experience relational issues as a high-risk group for suicidal ideation. Public programs and support systems should be established to improve daily life management and promote social relationships among older adults.

Keywords: Elderly, Self-neglect, Suicidal ideation, Gender, Moderator variables

INTRODUCTION

Given a rapidly aging population, maintaining mental health in older adults is a significant challenge faced by modern society. Suicide rates are an especially important indicator of the mental health status of society at large, and in Korea, they are concerningly high among older adults. In fact, the suicide rate of adults aged 60 years or older is higher in Korea than in any other member country of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development [1]. The crude suicide rate is also higher in older adults than in any other Korean age group [2]. Because a suicide attempt made by a physically weak older adult is likely to have fatal consequences [3], efforts to prevent suicidal ideation, which is a strong predictor of future attempts, are imperative.

While older adults may need extra help and care from others, they must also take care of themselves. However, a significant proportion of older adults put themselves in unhealthy and unsafe situations [4]. This pattern of behavior is known as self-neglect, which is more generally defined as a series of actions in which people give up on maintaining their well-being [5]. According to Orem [6] theory of self-care, physical ailments in older adults can lead to mental health problems, which can in turn result in a self-care deficit and or frank self-neglect. Considering suicide as an extreme form of self-neglect, other comparatively minor instances of self-neglect might serve as preconditions of suicidal ideation or attempts. Although there is limited evidence, a few previous studies have shown that self-neglect can result in detrimental physical and psychological health conditions, such as depression [5]. Because continued self-neglect can result in detrimental psychological outcomes [7], it should be explored as a predictor of suicide risk in older adults.

Potential gender differences in self-neglect and its impact on suicide risk should likewise be considered because men and women display different patterns of behavior in old age [8]. Some previous studies on gender differences in self-neglect among older adults showed contradictory results [9,10]. However, a nationwide survey conducted in Korea [11] showed that older men had a higher rate of self-neglect (55.6%) than women (44.4%) [10]. It is likely that for older men, the transition between work and retirement may disorient their ability to self-manage as they adjust to their new roles in society and in their families [12]. In fact, the psychological impact of this transition, as well as a general lack of social support, was explicitly found to increase self-neglect risk in older men [13]. Among older women, meanwhile, poor physical health and economic hardship were identified as factors increasing the risk of self-neglect. However, social support and interpersonal relationships could be protective factors against self-neglect among older women [7].

It also appears that the impact of certain factors on suicide risk varies between men and women. Retirement, unemployment, and poor physical health increased suicide risk among men, while factors related to social life and interpersonal relationships were more significant for women [14,15]. Statistics further show that older men are simply more vulnerable to suicide than older women. In Korea, 5.7% of women in their 60s, 4.5% of those in their 70s, and 3.1% of those in their 80s or over have attempted suicide, while in men in their 60s, 70s, and 80s or over, that rate was 9.4%, 7.6%, and 5.0% respectively [1].

Based on these considerations, it is clear that potential gender differences must be taken into account when assessing the association between self-neglect and suicidal tendencies. Some previous studies have examined the relationship between self-neglect in the elderly and suicide risk without considering gender, while others have focused on only one gender or on each outcome (difference in self-neglect or suicide risk) separately. The aim of this study, by contrast, was to examine whether gender had a moderating effect on the relationship between self-neglect and suicide risk in older adults. In addition, the relationships between 4 individual aspects of self-neglect (issues related to daily life management, personal hygiene, financial management, and relational factors) and suicide risk were also explored, as was gender’s potential moderating effect on these relationships.

METHODS

Research Materials and Participants

This study used survey data to determine the relationship between self-neglect and suicidal ideation, as well as the moderating effect of gender on this relationship, in adults aged 65 years or older. A cross-sectional study design was used, and data were collected via an online survey conducted through Korea Research, an agency with a research panel of approximately 700 000 individuals. Inclusion criteria for the study were Korean adults aged 65 or older. Online recruitment material was sent to potential participants, who freely decided whether to participate. The survey was conducted using a structured online questionnaire administered between October 21 and October 28, 2021. As calculated using G*Power version 3.1, the minimum sample size required was 135 study participants. The initial data included results from 612 participants, but only results from 356 participants were considered in the study; participants under the age of 65, as well as those whose survey responses were missing values relevant to the major variables of the study, were excluded.

Measuring Tools

Independent variables: self-neglect

The independent variables were self-neglect and its sub-dimensions. To measure these variables, the Self-Neglect Scale developed by Park and Kim [4], comprising 14 items ranked on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=agree, 4=strongly agree), was used. Each of the 14 items of the Self-Neglect Scale was assigned as appropriate to one of the 4 sub-dimensions of self-neglect, which were (1) daily life management issues, (2) personal hygiene management issues, (3) financial management issues, and (4) relational issues. For convenient interpretation, the items related to personal hygiene management were reverse coded, with a higher score representing a higher level of self-neglect. Cronbach’s α for all self-neglect items was 0.879.

Dependent variable: suicidal ideation

Suicidal ideation levels were assessed with an adapted version [16] of Harlow et al. [17]’s Suicidal Ideation Scale. The scale includes items such as “I recently told someone that I would commit suicide” and “I’ve attempted suicide before.” Each item was graded on a 5-point Likert-type scale (1=strongly disagree, 2=disagree, 3=neutral, 4=agree, 5=strongly agree). Higher scores corresponded to higher suicidal ideation levels. Cronbach’s α for all suicidal ideation items was 0.831.

Moderating and controlled variables

The moderating variable of gender was dummy-coded as 0 (men) or 1 (women). The controlled variables were age (a continuous variable), educational background (elementary school graduate=1, middle school graduate=2, high school graduate=3, university graduate=4, graduate school or higher education graduate=5), household size (1 person=1, 2 persons= 2, 3 persons=3, 4 persons=4, 5 persons or more=5), average monthly household income (1.00 million Korean won [KRW] or less=1, 1.01–2.00 million KRW=2, 2.01–3.00 million KRW=3, 3.01–4.00 million KRW=4, 4.01–5.00 million KRW=5, 5.01 million KRW or more=6), and the presence of a spouse (no spouse= 0, spouse=1).

Statistical Analysis

Frequency and descriptive analyses were performed to examine the demographic characteristics of the study sample and to analyze the main variables. The independent t-test was performed to confirm the difference in key variables between genders. Multiple regression analysis was used to investigate the association between self-neglect and suicidal ideation, as well as the moderating effect of gender on this association. Regression analyses were also performed to separately examine the associations between the 4 sub-dimensions of self-neglect and suicidal ideation. Stata version 15.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA) was used for all data analyses.

Ethics Statement

The research was conducted with approval from the Bioethics Committee (7001988-202110-HR-1380-02).

RESULTS

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in the upper part of Table 1. A total of 142 men (39.9%) and 214 women (60.1%) were surveyed, and the average age of the participants was 68.15 years (standard deviation [SD], 3.62). Regarding educational background, those with a high school diploma or higher accounted for 93.5% of all participants. There were 33 participants (9.3%) from single-person households, 161 participants (45.2%) from two-person households, 93 participants (26.1%) from 3-person households, 50 participants (14.0%) from 4-person households, and 19 participants (5.3%) from households with 5 or more people. In terms of average monthly household income, 76 participants (21.3%) were from households whose income ranged from 1.01 to 2.00 million KRW per month, the most out of any income category. Meanwhile, only 28 participants (7.9%) were from households whose income was 1.00 million KRW or less per month, the least out of any income category. Among the participants, 61 (17.1%) had no spouse, while 295 (82.9%) had a spouse.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study sample (n=356)

| Characteristics | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Men | 142 (39.9) |

| Women | 214 (60.1) |

|

| |

| Age (y) | |

| Average±SD | 68.15±3.62 |

|

| |

| Level of education | |

| Elementary school or less | 2 (0.6) |

| Middle school | 21 (5.9) |

| High school | 130 (36.5) |

| College (university) degree | 144 (40.4) |

| Graduate school or higher | 59 (16.6) |

|

| |

| Household income (×10 000 Korean won/mo) | |

| ≤100 | 28 (7.9) |

| 101–200 | 76 (21.3) |

| 201–300 | 69 (19.4) |

| 301–400 | 72 (20.2) |

| 401–500 | 52 (14.6) |

| ≥501 | 59 (16.6) |

|

| |

| Household size (person) | |

| 1 | 33 (9.3) |

| 2 | 161 (45.2) |

| 3 | 93 (26.1) |

| 4 | 50 (14.0) |

| ≥5 | 19 (5.3) |

|

| |

| Living with a spouse | |

| Yes | 295 (82.9) |

| No | 61 (17.1) |

SD, standard deviation.

Characteristics of Main Variables

The characteristics of the main variables are shown in Table 2, which shows that the average score for self-neglect was 1.50 points out of 4 (SD, 0.39). Out of the self-neglect sub-dimensions, personal hygiene management issues had the highest average score of 1.72 points out of 4 (SD, 0.54). By comparison, financial management averaged 1.46 points (SD, 0.53), relationship factors averaged 1.46 points (SD, 0.56), and daily life management averaged 1.41 points (SD, 0.42), all out of 4. The average score for suicidal ideation was 1.81 points out of 5 (SD, 0.77).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistical analysis and differences in the main variables according to gender

| Variables | Total (n=356) | Men (n=142) | Women (n=214) | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-neglect | 1.50±0.39 | 1.52±0.39 | 1.49±0.38 | 0.764 |

|

| ||||

| Self-neglect sub-factors | ||||

| Daily life management factors | 1.41±0.42 | 1.40±0.43 | 1.42±0.41 | −0.380 |

| Personal hygiene management factors | 1.72±0.54 | 1.70±0.51 | 1.73±0.55 | −0.535 |

| Financial management factors | 1.46±0.53 | 1.51±0.56 | 1.43±0.51 | 1.262 |

| Relational factors | 1.46±0.56 | 1.49±0.63 | 1.39±0.51 | 1.638 |

|

| ||||

| Suicidal ideation | 1.81±0.77 | 1.82±0.79 | 1.81±0.77 | 0.079 |

Values are presented as average±standard deviation.

Differences in Main Variables Across Genders

The independent t-test was performed to evaluate potential differences in the main variables according to gender. As shown in Table 2, no statistically significant differences in self-neglect, the sub-dimensions of self-neglect, or suicidal ideation were found between men and women.

Research Model Verification

Table 3 shows the effects of overall self-neglect on suicidal ideation in older adults, as well as the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between self-neglect and suicidal ideation. The explanatory power of self-neglect for suicidal ideation was 16.4% (R2=0.164), and the regression equation was statistically significant (F=8.480, p<0.001). The relationship between the key variables showed that the independent variable (B=0.669, p<0.001) significantly affected suicidal ideation. In other words, a higher level of self-neglect was associated with a higher degree of suicidal ideation. However, the controlled variables (age, level of education, household size, average monthly household income, and the presence of a spouse) and the moderating variable (gender) had no significant effect on suicidal ideation. Additionally, it was confirmed that the interaction term self-neglect×gender did not significantly affect suicidal ideation. Therefore, gender did not have a significant moderating effect on the relationship between self-neglect and suicidal ideation in older adults.

Table 3.

The moderating effect of gender on the relationship between self-neglect and suicidal ideation in older adults

| Variables | Model 1 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Coefficient | Standard error | |

| Independent variable | ||

| Self-neglect (A) | 0.669*** | 0.157 |

|

| ||

| Controlled variables | ||

| Age | 0.013 | 0.011 |

| Level of education (ref: elementary school or less) | −0.014 | 0.048 |

| Household size | −0.025 | 0.040 |

| Household income | −0.002 | 0.027 |

| Living with a spouse (ref: no) | 0.049 | 0.109 |

|

| ||

| Moderating variables | ||

| Gender (ref: men) (B) | 0.669*** | 0.317 |

|

| ||

| Interaction | ||

| A×B | 0.199 | 0.201 |

|

| ||

| Constant | 0.033 | 0.862 |

|

| ||

| R 2 | 0.164 | |

|

| ||

| F(sig.) | 8.480*** | |

ref, reference; sig., significant.

p<0.001.

Table 4 shows the effects of the 4 sub-dimensions of self-neglect on suicidal ideation in older adults, as well as the moderating effect of gender on the relationships between each of these sub-dimensions and suicidal ideation. The explanatory power for suicidal ideation was 21.5% (R2=0.215), and the regression equation was statistically significant (F=6.650, p<0.001). Among the 4 sub-dimensions of self-neglect, daily life management issues (B=0.640, p<0.01) and relational issues (B=0.203, p<0.05) had significant effects on suicidal ideation. That is, higher levels of self-neglect related to daily life management and relational issues were associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation. However, the controlled variables (age, level of education, household size, average monthly household income, and the presence of a spouse) and the moderating variable (gender) had no significant effect on suicidal ideation. Regarding the interaction terms, the relational issues×gender interaction term did show a significant impact on suicidal ideation (B=0.336, p<0.05). Thus, gender had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between the relational dimension of self-neglect and suicidal ideation in older adults. The other interaction terms were not found to significantly affect suicidal ideation.

Table 4.

The moderating effect of gender on the relationships between the sub-factors of self-neglect and suicidal ideation in older adults

| Variables | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Coefficient | Standard error | |

| Independent variables | ||

| Daily life management factors (A) | 0.640** | 0.190 |

| Personal hygiene management factors (B) | −0.197 | 0.128 |

| Financial management factors (C) | −0.012 | 0.134 |

| Relational factors (D) | 0.203* | 0.114 |

|

| ||

| Controlled variables | ||

| Age | 0.015 | 0.011 |

| Level of education (ref: elementary school or less) | −0.055 | 0.048 |

| Household size | −0.021 | 0.039 |

| Household income | 0.004 | 0.027 |

| Living with a spouse (ref: no) | 0.087 | 0.108 |

|

| ||

| Moderating variables | ||

| Gender (ref: men) (E) | −0.444 | 0.324 |

|

| ||

| Interaction | ||

| A×E | −0.365 | 0.251 |

| B×E | 0.184 | 0.160 |

| C×E | −0.110 | 0.185 |

| D×E | 0.336* | 0.173 |

|

| ||

| Constant | 0.142 | 0.848 |

|

| ||

| R 2 | 0.215 | |

|

| ||

| F (sig.) | 6.650*** | |

ref, reference; sig., significant.

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

p<0.001.

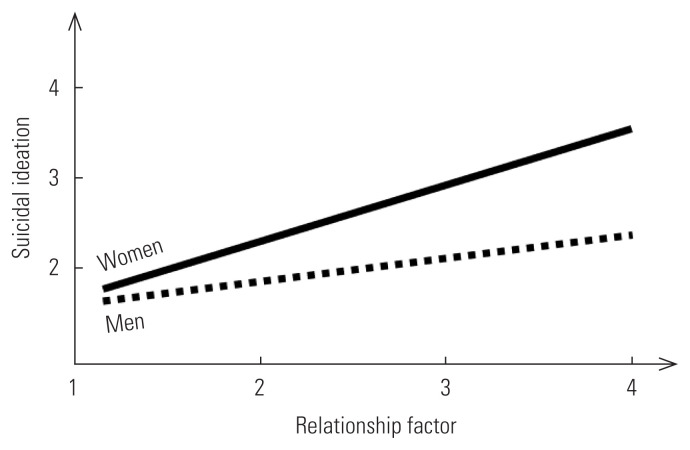

Figure 1 shows the moderating effect of gender on the relationship between the relational dimension of self-neglect and suicidal ideation. As shown in the figure, increased self-neglect related to relational issues was associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation in both genders. However, the effect of these relational issues on suicidal ideation was more pronounced in women than in men. This is apparent from Figure 1, which shows that suicidal ideation increased more rapidly along with the relational dimension of self-neglect in women than in men.

Figure 1.

The moderating effect of gender on the relationship between self-neglect related to relational factors and suicidal ideation.

DISCUSSION

Suicide is one of the most concerning health-related issues among older adults in Korea. Even though older adults are at a higher risk of both self-neglect and suicide, few studies have explored the association between these variables. This study sought to remedy that gap by exploring the relationship between self-neglect and suicidal ideation in a sample of 356 older Korean adults. It also examined the potential moderating effect of gender on this relationship. In addition, we aimed to examine the effect of specific aspects or dimensions of self-neglect on suicidal ideation. The effects of self-neglect and its subdimensions on suicidal ideation were examined through multiple regression analysis.

The findings show that self-neglect as a whole was significantly associated with suicidal ideation (B=0.669) in older adults. Self-neglect related to daily life management (B=0.640) and relational issues (B=0.203) specifically were also found to be significantly related to suicidal ideation. These findings are consistent with previous studies showing the effect of self-neglect on suicidal ideation in older adults [18]. One study, for instance, showed that suicidal thoughts followed instances of self-neglect in older adults and further that suicidal ideation increased in those displaying poor daily life management skills manifesting as a lack of cleanliness and poor hygiene [19]. It has also been shown that older adults who are unable to maintain good social relationships are at greater risk of suicidal ideation. This aligns with other research that emphasizes relationship dimensions such as social participation, family support, and loneliness as important predictors of suicide risk in older adults [20–22].

Many previous studies have also pointed out that risk factors for suicide may differ by gender and that older women in particular are more vulnerable to suicidal ideation when facing family crises or unfavorable changes in family relationships [23,24]. These ideas align with the findings of our study, in which gender was found to have a significant moderating effect on the relationship between relational issues and suicidal ideation. In particular, self-neglect related to relational issues was more closely associated with suicidal ideation in older adult women than in older men (B=0.336).

Based on these findings, we can make a few suggestions for suicide prevention in self-neglecting older adults. First, it is necessary to actively seek groups of older adults who may be more likely to neglect themselves and therefore be more vulnerable to suicide. This accords with Article 39-6 of Korea’s Elderly Welfare Act, whereby certain occupational groups (medical personnel, nursing care social workers, etc.) are obligated to report self-neglect as a potential warning sign of elder abuse. Experts in these fields should treat evidence of self-neglect as an indication of possible suicide risk in older adults, further keeping in mind that people with severe depression or cognitive impairment are more likely to experience self-neglect [25]. It is also necessary that local governments regularly monitor suicide risk in their respective communities. By identifying instances of self-neglect, it may be possible to identify and treat those older adults at high risk of suicide who might have otherwise gone unidentified. Moreover, we propose that local governments create initiatives to prevent social isolation and actively promote social relationships among older adults [26]. Local governments are currently providing care for older adults through customized care services and community facilities, but it is a challenge to provide care services through classes focusing on the detailed characteristics of the target groups [27]. Therefore, it is crucial to strengthen the structures that support relationship improvement and daily life by considering the characteristics of self-negligent older adults in public programs.

Second, in light of our finding that relational issues are more closely associated with suicide risk in older women than in older men, some public policy interventions should be considered. In particular, it may be necessary to screen high-risk groups, especially self-neglecting older women, for depression and other psychological issues in order to identify potential adverse social or relationship changes that may heighten suicide risk.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the temporal ordering of the independent variables (self-neglect and its sub-dimensions) and the dependent variable (suicidal ideation) is uncertain due to the cross-sectional design of the study. In other words, it is impossible to know whether instances of self-neglect preceded suicidal ideation as both were reported in a single survey. Thus, the relationship between self-neglect and suicidal ideation should be interpreted as correlational rather than causal. To exclude the possibility of endogeneity and a reverse causal relationship between these variables, future research should adopt a time-series design rather than a cross-sectional one. Second, because all participants were between the ages of 65 years and 70 years old and because many household characteristics were not assessed in the survey, the study sample may have been relatively uncharacteristic of the population of older adults in Korea. The degree to which the study results can be generalized may, therefore, be limited. Another difficulty was that although the investigation of older adults who live alone was considered essential to the researchers, relatively few participants fell into this category, meaning that a comparative analysis of this group could not be performed. Overall, we suggest that future research should consider a more diverse range of ages and household characteristics. Further, in light of the finding that relational issues are more closely associated with suicide risk in older women than in older men, we also suggest that follow-up studies examine mediating effects in order to investigate the potential path from relational issues to suicide in older adult women.

The findings of this study show that the different aspects of self-neglect are associated with suicidal ideation in older adults to varying degrees. Among all the aspects of self-neglect, poor daily life management and relational issues were identified as particularly important risk factors for suicidal ideation. Our findings also showed that the relational dimension of self-neglect was a stronger risk factor for suicidal ideation in women than in men. To address these issues, we suggest that programs aimed at preventing suicide in older adults should focus on daily life management and relationship issues. We also suggest that these programs focus on facilitating and enhancing the social lives of older women in particular, since relationship issues were shown in this study to be a stronger risk factor for suicidal ideation in older women than in older men.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest associated with the material presented in this paper.

FUNDING

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Jeong K. Data curation: Jeong K. Formal analysis: Jeong K. Funding acquisition: None. Methodology: Jeong K. Project administration: Jang D. Visualization: Jeong K, Jang D. Writing – original draft: Jeong K, Jang D, Nam B, Kwon S, Seo E. Writing – review & editing: Jang D.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ministry of Health and Welfare; Korea Foundation for Suicide Prevention 2021 White paper on suicide prevention. [cited 2022 Jan 27]. Available from: https://www.bokjiro.go.kr/ssis-teu/cms/pc/news/promotion/__icsFiles/afieldfile/2021/08/30/162547124180998.pdf(Korean)

- 2.Statistics Korea Statistics on causes of death in 2019. 2020. [cited 2022 Jan 27]. Available from: https://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/6/2/index.board?bmode=read&bSeq=&aSeq=385219&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&searchInfo=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (Korean)

- 3.Van Orden K, Conwell Y. Suicides in late life. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;13(3):234–241. doi: 10.1007/s11920-011-0193-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park MJ, Kim J. Development and validation study of self-neglect scale for older adults: focusing on community-living elderly adults. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf. 2015;69(69):99–121. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dyer CB, Franzini L, Watson M, Sanchez L, Prati L, Mitchell S, et al. Future research: a prospective longitudinal study of elder self-neglect. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(Suppl 2):S261–S265. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orem DE. A concept of self-care for the rehabilitation client. Rehabil Nurs. 1985;10(3):33–36. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.1985.tb00428.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kown JD, Kim Y, Lim TY. The meaning and pathways of suicidal experiences among older adults: a grounded theory method. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf. 2011;52:419–446. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wakabayashi C, Donato KM. Does caregiving increase poverty among women in later life? Evidence from the Health and Retirement survey. J Health Soc Behav. 2006;47(3):258–274. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abrams RC, Lachs M, McAvay G, Keohane DJ, Bruce ML. Predictors of self-neglect in community-dwelling elders. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1724–1730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dong X, Simon MA, Wilson RS, Mendes de Leon CF, Rajan KB, Evans DA. Decline in cognitive function and risk of elder self-neglect: finding from the Chicago Health Aging Project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(12):2292–2299. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ministry of Health and Welfare Elder abuse status report 2020. 2021. [cited 2022 Jan 27]. Available from: http://www.mohw.go.kr/react/gm/sgm0701vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=13&MENU_ID=1304081001&CONT_SEQ=366538 (Korean)

- 12.Seok JE. New elderly culture and the potential of reciprocal relationship resource on elderly-friendly community design integrated with generations in super-aged society. Seoul: Meerae Forum; 2016. pp. 89–114. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim MY, Lee JJ. Risk factors for self neglect of elderly males in the community. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf. 2016;71(3):29–51. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qin P, Agerbo E, Westergård-Nielsen N, Eriksson T, Mortensen PB. Gender differences in risk factors for suicide in Denmark. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:546–550. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.6.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Payne S, Swami V, Stanistreet DL. The social construction of gender and its influence on suicide: a review of the literature. J Mens Health. 2008;5(1):23–35. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim HS. A study on epistemology of Korean elder’s suicidal thought. J Korean Gerontol Soc. 2002;22(1):159–172. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harlow LL, Newcomb MD, Bentler PM. Depression, self-derogation, substance use, and suicide ideation: lack of purpose in life as a mediational factor. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42(1):5–21. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(198601)42:1<5::aid-jclp2270420102>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moon DK. A meta-regression analysis on related triggering variables on the suicidal ideation of older adults. Korean J Geronto Soc Welf. 2012;55:133–157. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong X, Xu Y, Ding D. Elder self-neglect and suicidal ideation in an US Chinese aging population: findings from the PINE study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017;72(Suppl_1):S76–S81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glw229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee MS. Does the social activity of the elderly mediate the relationship between social isolation and suicidal ideation? Ment Health Soc Work. 2012;40(3):231–259. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim MH, Moon JW. The impact of family and social relationships on depression and suicidal ideation of the elderly. Korea Acad Care Manag. 2013;10:1–26. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee I. Moderating effects of life problems, social support on the relationship between depression and suicidal ideation of older people. Health Soc Welf Rev. 2011;31(4):34–62. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim KT, Choi SS, Park MJ, Park S, Ko SH, Park H. The effect of family structures and psycho-social factors on suicidal ideation of senior citizens. Korean J Gerontol Soc Welf. 2011;52:205–228. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim HS, June KJ, Kim YM. Gender differences in factors affecting suicidal ideation among the Korean elderly. J Korea Gerontol Soc. 2013;33(2):349–363. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abrams RC, Lachs M, McAvay G, Keohane DJ, Bruce ML. Predictors of self-neglect in community-dwelling elders. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1724–1730. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hwang JW, Lee KU, Kim JY, Lee DH, Kim DM. The affection of depression of the elderly living together and the elderly living alone on suicidal ideation and the moderating effects of personal relation. Ment Health Soc Work. 2017;45(1):36–62. (Korean) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MJ, Kim MH. Problems and improvement plan of customized care service for the elderly. Daejeon: Daejeon Public Agency for Social Service; 2020. (Korean) [Google Scholar]