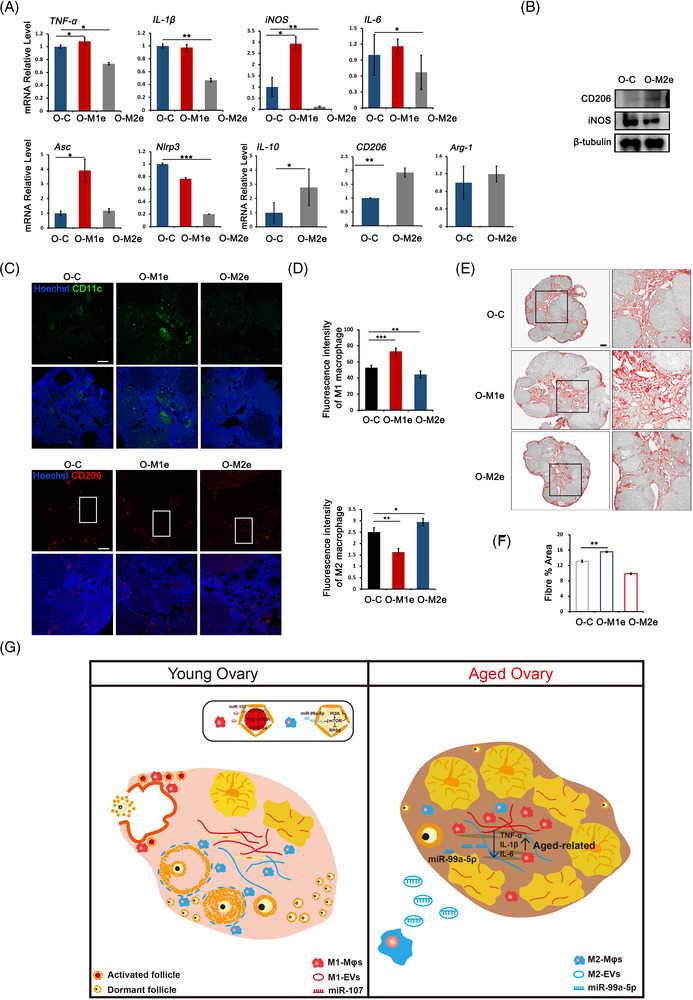

FIGURE 7.

M2‐extracellular vesicles (EVs) changed inflammatory microenvironment in aged ovaries. Mice at 10‐month of age were tail intravenous injected with 100 μl phosphate‐buffered saline (PBS) containing 15 μg M1‐, M2‐EVs (O‐M1e and O‐M2e) and same volume of PBS (O‐C) five times for 28 days, respectively. (A) The expression of pro‐inflammatory genes and anti‐inflammatory genes in aged ovaries of three groups. (B) Western blot of iNOS and CD206 expression in O‐C and O‐M2e ovaries. The expression of β‐tubulin was used as internal control. (C) Immunofluorescence labelling of CD11c and CD206 in aged ovaries treated with PBS, M1‐EVs and M2‐EVs. (D) Fluorescent intensity of CD11c and CD206 in ovaries of each group. (E) Representative processed colour threshold images of Masson‐stained ovarian tissue sections in ovaries of different groups. Right panels represent the magnified image of black frames. (F) Quantification of ovarian fibrosis by Masson‐stain after mice were treated with PBS, M1‐ or M2‐EVs. (G) A schematic diagram depicts the role of macrophages (Mφs) in regulating primordial follicle activation after physiological ovulation and ovarian inflammatory environment during ovarian ageing. Left panel: an inflammatory environment consisting of M1 Mφs that gather around the ovulation site stimulates primordial follicles activation in each menstrual cycle. Right panel: the accumulation of M1 Mφs in aged ovaries induces a pro‐inflammatory environment and reduced ovarian function. M2‐EVs treatment alters the inflammatory microenvironment and improves ovarian function in aged ovaries at least partly through M2‐EVs contained miRNA, miR‐99a‐5p. Data represent the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of biological triplicate experiments. * p < .05, ** p < .01 and *** p < .001, by one‐way analysis of variance (ANOVA) analysis. Scale bars: 50 μm