Significance

Pharmacological induction of autophagy usually involves small molecules targeting intracellular signaling cascades. Here, Motiño et al. demonstrate that monoclonal antibody–mediated neutralization of an extracellular inhibitor of autophagy, acyl-coenzyme A binding protein (ACBP)/diazepam-binding inhibitor (DBI), stimulates cytoprotective autophagy, hence inhibiting cell loss, inflammation, and fibrosis in various disease models affecting liver, lung, and myocardium. Extracellular ACBP/DBI acts as an autophagy checkpoint on GABAA receptors, hence offering a target for a new class of autophagy checkpoint inhibitors.

Keywords: acyl-CoA binding protein, autophagy, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, myocardium infarction, fibrosis

Abstract

Acyl-coenzyme A (CoA)–binding protein (ACBP), also known as diazepam-binding inhibitor (DBI), is an extracellular feedback regulator of autophagy. Here, we report that injection of a monoclonal antibody neutralizing ACBP/DBI (α-DBI) protects the murine liver against ischemia/reperfusion damage, intoxication by acetaminophen and concanavalin A, and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis caused by methionine/choline-deficient diet as well as against liver fibrosis induced by bile duct ligation or carbon tetrachloride. α-DBI downregulated proinflammatory and profibrotic genes and upregulated antioxidant defenses and fatty acid oxidation in the liver. The hepatoprotective effects of α-DBI were mimicked by the induction of ACBP/DBI-specific autoantibodies, an inducible Acbp/Dbi knockout or a constitutive Gabrg2F77I mutation that abolishes ACBP/DBI binding to the GABAA receptor. Liver-protective α-DBI effects were lost when autophagy was pharmacologically blocked or genetically inhibited by knockout of Atg4b. Of note, α-DBI also reduced myocardium infarction and lung fibrosis, supporting the contention that it mediates broad organ-protective effects against multiple insults.

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as “autophagy”) is a process through which portions of the cytoplasm are sequestered in autophagosomes, which subsequently fuse with lysosomes for the enzymatic hydrolysis of the autophagic cargo (1). Although autophagy is often observed in the context of cell death, it preponderantly subserves cytoprotective functions. Thus, excessive autophagy leading to cellular demise (“autophagic cell death” or “autosis”) is a rare phenomenon. Rather, in most instances, cell stress–induced autophagy delays or avoids cell death by facilitating cellular adaptation (2–4). This stress-adaptive function of autophagy results from a combination of factors, including, but not limited to, (i) the mobilization of macromolecules, including proteins, messenger RNA (mRNA), lipids, and glycogen, to generate energy-rich metabolites and building blocks for anabolic reactions and (ii) the selective removal of damaged cellular structures, including aggregates of misfolded proteins, uncoupled or permeabilized mitochondria, as well as other dysfunctional organelles (4–6). As a result, cellular fitness is improved in a cell-autonomous fashion. Moreover, the activation of proinflammatory pathways is blunted by autophagy due to the removal of molecules (such as cytosolic DNA or reactive oxygen species) that may activate endogenous pattern-recognition receptors, as well as due to the downregulation of the downstream signals emanating from such receptors (2, 7, 8).

Given its preponderant role in the turnover of cytoplasmic structures, experimental inhibition of autophagy accelerates the time-dependent degeneration of organelles, cells, organs, and the entire organism. Genetic defects that attenuate autophagy can specifically affect distinct organs or cause multiorgan syndromes (9, 10). Moreover, normal aging and obesity, the most-prevalent pathological condition in humans, are associated with reduced autophagic flux (11). Conversely, genetic manipulations aiming at inducing autophagy have a broad antiaging effect, as this has been demonstrated in mice by transgenic overexpression of the essential autophagy gene Atg5 (12) or by gain-of-function mutation of Beclin 1 (13). Of note, it appears that many lifespan- and healthspan-extending manipulations, be they nutritional (such as caloric restriction or oral supplementation with spermidine), pharmacological (such as administration of rapamycin), or genetic (such as interruption of the insulin/insulin growth factor receptor or removal of tumor suppressor protein p53) require autophagy for being efficient (14–19). In view of these rather broad health-improving effects of autophagy, its induction has been proposed as a general strategy to combat diseases affecting specific organs, including liver (11, 20, 21), heart (22), lung (23), or kidney (24, 25). As an example, autophagy induction can prevent the development of multiple hepatic pathologies, including, but not limited to, acetaminophen-induced liver failure (26), nonalcoholic hepatosteatosis (NASH) (27), liver fibrosis and cirrhosis induced by alcohol or toxins (28), as well as cholestasis-induced hepatitis (21).

The pharmacological induction of autophagy is typically achieved by drugs acting on intracellular energy sensors, including mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 and E1A-associated protein, which must be inhibited to induce autophagy, and sirtuin-1 or adenosine monophosphate–activated kinase, which must be activated to induce autophagy (19, 29, 30). Other classes of autophagy inducers disrupt the inhibitory interaction of B cell lymphoma 2 with the proautophagic lipid kinase complex composed by beclin-1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 3 (31) or activate the lysosomal calcium channel TRPML1 (32).

Recently, we described an extracellular feedback loop of autophagy that involves the protein acyl coenzyme A–binding protein (ACBP), which is called by diazepam-binding inhibitor (DBI) (10). Indeed, autophagy is tied to the atypical secretion of this leaderless protein that is predominantly present in the cytosol of nucleated cells (10, 33). Once released into the extracellular space, ACBP/DBI then acts on gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors to inhibit autophagy via autocrine, paracrine, and neuroendocrine pathways (10, 34). When injected intraperitoneally or intravenously, a monoclonal antibody (mAb) against ACBP/DBI (dubbed as α-DBI) remarkably reduced high-fat diet–induced adiposity, diabetes, and hepatosteatosis while enhancing autophagy, lipolysis, and β-oxidation and simultaneously reducing appetite (10, 34, 35). These effects were considered to be on target, because they could be mimicked by inducible whole-body knockout of ACBP/DBI (10). Intrigued by these observations, we decided to investigate the potential of α-DBI on different organs (liver, heart, and lung) damaged by a series of drugs, toxins, or ischemic insults. Here, we report the broad organ-protective, autophagy-dependent effects of α-DBI.

Material and Methods

We used mouse models of cardiac ischemia (induced by ligation of the left anterior descending coronary artery (36)), liver ischemia reperfusion (37), NASH induced by a methionine choline–deficient diet (MCD) (as opposed to regular chow diet [RCD]), liver fibrosis (induced by bile duct ligation or CCL4 injections) (38, 39), and lung fibrosis (induced by bleomycin) (40). Data are expressed as means ± SEM. SI Appendix includes experimental and statistical details.

Results

Hepato- and Cardio-Protective Effects of ACBP/DBI Neutralization against Acute Insults.

Injection of a mAb-neutralizing ACBP/DBI (α-DBI) (2.5 µg/g intraperitoneally [i.p.], 6 and 2 h before sacrifice) enhances the hepatic lipidation of microtubule-associated proteins 1A/1B light chain 3B (hereafter referred to as LC3B), a marker of autophagy, giving rise to the electrophoretically more-mobile LC3-II form (Fig. 1 A and B) (41). This effect was further enhanced by injection of the lysosomal protease inhibitor leupeptin (30 mg/kg i.p., 2 h before sacrifice), corroborating the elevated autophagic flux (42) (Fig. 1 A and B). Accordingly, a single injection of α-DBI (2.5 µg/g i.p., 4 h before sacrifice) induced the formation of autophagic puncta in hepatocytes from mice expressing a transgene encoding a green fluorescent protein-LC3 fusion protein (41) (Fig. 1 C and D). Two injections of α-DBI (Fig. 1E) also reduced the histological signs of ischemia/reperfusion (congestion, ballooning, and necrosis summed up in the Suzuki score) (43) of the liver (Fig. 1 F and G), as well as an increase in the plasma concentrations of the two transaminases alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (Fig. 1 H and I). When α-DBI injection was combined with hydroxychloroquine (50 mg/kg), a lysomotropic agent that inhibits autophagy in vivo (44), the hepatoprotective effects of ACBP/DBI neutralization against ischemia/reperfusion were lost (Fig. 1 F–I). Similar hydroxychloroquine-inhibitable, hepatoprotective effects of α-DBI were obtained in two models of pharmacological hepatotoxicity caused by acetaminophen (APAP) (trade name: paracetamol) and the lectin concanavalin A (ConA) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1A). In both models, α-DBI reduced histological signs of hepatic injury (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 B, C, F, and G), as well as circulating transaminase levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S1 D, E, H, and I). Importantly, α-DBI also induced signs of autophagic flux in the myocardium (Fig. 2 A and B), including signs of mitophagy, as measured by means of the fluorescent biosensor Mito-Keima (45) (Fig. 2 C and D). Moreover, α-DBI injection (Fig. 2E) reduced myocardial infarction provoked by ligation of the left coronary artery, and this cardioprotective effect was lost when the essential autophagy gene Atg7 was floxed and selectively knocked out in heart by a CRE recombinase specifically expressed in cardiomyocytes (genotype: αMHC-Cre::Atg7f/f) (Fig. 2 F and G).

Fig. 1.

Neutralization of ACBP/DBI activates autophagy flux and attenuates ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo. (A and B) C57BL/6 mice were injected intraperitoneally (i.p.) with a monoclonal antibody (mAb) neutralizing ACBP/DBI (α-DBI) or control isotype (IgG) (2.5 µg/g i.p., 6 and 2 h before sacrifice) and the autophagy flux inhibitor leupeptin (Leu) (30 mg/kg, 2 h before sacrifice). Representative Western blot (A) and densitometric quantification (B) from the liver tissues, upon normalization (relative expression [RE]) to the LC3B II/I ratio (n = 6 mice per group). (C and D) Representative confocal images (C) and LC3 dots quantification (counts/100 mm2) (D) from livers recovered from LC3-GFP transgenic mice after i.p. injection of α-DBI or IgG (2.5 µg/g, 4 h before sacrifice) (n = 5 mice per group). (E–I) Liver injury produced by ischemia/reperfusion (IR) for 90 min/4 h. Schematic representation (E) of the damage induced by hepatic IR in mice pretreated with i.p. injection of α-DBI or IgG (2.5 µg/g) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) (50 mg/kg) for 4 h and just before IR. Representative images of hematoxylin/eosin/safranin-stained (HES) liver section (F) from mice pretreated with α-DBI or IgG and HCQ after sham operation or IR. Asterisk, arrows, and arrowheads indicate necrotic areas, vacuolization, and vascular congestion, respectively. The liver injury (G) was assessed by histological examination. ALT (H) and AST (I) transaminase activity in plasma was analyzed by means of a colorimetric assay (n = 4–11 mice per group). Results are displayed as means ± SEM. For statistical analyses, P values were calculated by ANOVA test (B and G–I) or two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (D).

Fig. 2.

ACBP/DBI neutralization activates autophagy/mitophagy flux and reduces cardiac damage in mice. (A and B) α-DBI or IgG (2.5 µg/g, 6 and 2 h before sacrifice) and leupeptin (30 mg/kg, 2 h before sacrifice) were injected i.p. in C57BL/6 mice. Immunoblot of LC3B (A) and densitometric quantification (B) from heart extracts (n = 6 mice per group). (C and D) Mito-Keima transgenic mice were injected twice with IgG or α-DBI i.p. 6 and 2 h before sacrifice (2.5 µg/g). Representative confocal microscopy images (C) and quantification of signals (D) (n = 3 mice per group). (E–G) Wt (Atg7fl/fl, αMHC Cre−) and homozygous Atg7−/− (Atg7fl/fl, αMHC Cre+) mice were subjected to 3 h of ischemia (E). Mice were injected with IgG or α-DBI i.p. 4 h before ischemia and just before ischemia. Representative images of left ventricular myocardial sections after Alcian blue and 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride staining (F) and quantification of the infarction size versus area at risk of myocardial damage (G) (n = 4–6 mice per group). Results are displayed as means ± SEM. For statistical analyses, P values were calculated by ANOVA test (B and G) or two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (D). AAR, area at risk.

In conclusion, mAb-mediated neutralization of ACBP/DBI induces autophagy in the liver and in the heart and protects hepatocytes and cardiomyocytes against acute damage in an autophagy-dependent fashion.

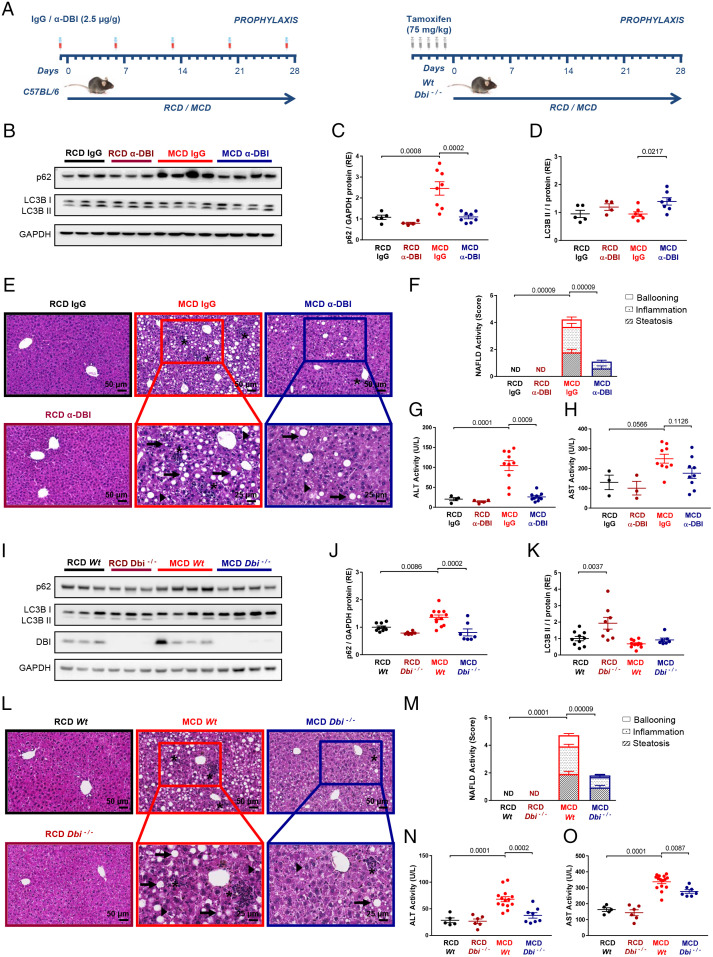

NASH-Preventive Effects of Immunological or Genetic ACBP/DBI Inhibition.

ACBP/DBI neutralization attenuates high-fat diet (HFD)–induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (10). However, since ACBP/DBI neutralization also reduces HFD-induced obesity (10), it is not clear whether this liver-protective effect is direct or secondary to weight reduction. Here, we investigated the effects of ACBP/DBI neutralization on a model of NASH that occurs in the context of weight loss, as the result of a MCD (control: RCD) (38). NASH features were evaluated after a 4-wk course of MCD in mice receiving weekly injections of α-DBI (control: isotype immunoglobulin G [IgG] mAb) or in the context of a tamoxifen-inducible whole-body knockout of floxed Acbp/Dbi−/− (genotype: UBC-cre/ERT2::Acbp/Dbif/f, control: Acbp/Dbif/f without CRE) (Fig. 3A). MCD results in the accumulation of the autophagic substrate sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1, best known as p62), suggesting reduced autophagic flux, and this effect was reversed by α-DBI (Fig. 3 B and C). Accordingly, α-DBI increased LC3B lipidation as a sign of autophagy induction (Fig. 3 B and D). α-DBI largely prevented the histological (steatosis, ballooning, and inflammation) and enzymological signs (ALT and AST) of NASH induced by MCD (Fig. 3 E–H). Genetic ablation of Acbp/Dbi similarly protected against MCD-associated NASH, as it increased autophagic flux (Fig. 4 I–K) and obviated the MCD-induced histopathological alterations (Fig. 3 L and M) as well as the transaminase elevation (Fig. 3 N and O). Of note, in these experiments, both α-DBI and the Acbp/Dbi knockout reduced the spontaneous weight gain of mice kept on RCD but counteracted the weight loss caused by MCD (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 A and C). Moreover, α-DBI caused a reduction in the liver Acbp/Dbi mRNA levels, though less than the Acbp/Dbi knockout (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 B and D). Alternately, we neutralized ACBP/DBI by a third protocol consisting in the autoimmunization of mice with recombinant ACBP/DBI fused to the potent immunoadjuvant keyhole limpet hemocyanin (KLH) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2E) (10, 46). Prophylactic induction of ACBP/DBI-specific autoantibodies also ameliorated the induced weight loss and Acbp/Dbi mRNA expression (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 F and G) and reversed the MCD-induced autophagic blockade (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 H–J), as well as the signs of NASH (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 K–M). Finally, we took advantage of mice in which the γ2 subunit of GABAA receptor is mutated (F77I) to abolish ACBP/DBI binding (47). Such mice were relatively resistant against MCD-induced NASH (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 N–P).

Fig. 3.

ACBP/DBI neutralization and ablation protect against MCD-induced hepatic steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning in vivo. (A) Experimental strategy of the NASH injury induced by MCD for 4 wk (control with regular chow diet [RCD]). C57BL/6 mice were injected i.p. with α-DBI or IgG (2.5 µg/g) 1 d before the beginning of the diet and every week during the diet (Left). Inducible whole-body knockout of Acbp/Dbi (Dbi−/−) or control (Wt) mice were injected i.p. with tamoxifen daily for 5 d (Right). (B–H) α-DBI reduces the hepatic damage produced by MCD diet through autophagy activation. Representative immunoblot (B) and densitometric analysis of the ratio LC3B II/I (C) and p62 (D) normalized against GAPDH (both expressed as RE) from liver extracts. Hepatic HES images (E) and NAFLD activity score (measured as sum of steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning score) (F) and ALT (G) and AST activity (H) in plasma from mice treated with α-DBI or IgG (n = 3–10 mice per group). (I–O) Genetic ablation of ACBP/DBI reverts derived-NASH diet nocuous effect by autophagy activation. Western blots (I) and densitometric analysis of p62 (J), LC3B (K), and DBI from liver extracts. Histological pictures from liver HES staining (L), NAFLD activity score (M), and hepatic damage measured by plasmatic levels of ALT (N) and AST activity (O) from Dbi−/− and Wt mice (n = 5–16 mice per group). Asterisk, arrows, and arrowheads indicate inflammation foci, macrosteatosis, and microsteatosis vesicular, respectively. Data are displayed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses (P value) were calculated by ANOVA test.

Fig. 4.

Metabolic and proautophagic effects of α-DBI in the context of MCD. (A) Heatmap clustered by Euclidean distance of changes in liver metabolite concentrations depicted as log2 (fold change) (FC) in C57BL/6 mice injected with IgG or α-DBI after MCD (Left) (n = 3–9 mice per group). All carnitines are depicted in the Right. (B–D) Expression of β-oxidation-relevant enzymes. Representative Western blot (Top) and densitometric quantification (Bottom) of CPT1A after (B) (n = 5–8 mice in each group). mRNA levels of Cpt1a (C) and Ppara (D) analyzed by qRT-PCR (n = 4–8 mice per group). (E–L) Comparison of anti-NASH effects of α-DBI in Wt and autophagy-deficient (Atg4b−/−) mice under MCD. Representative immunoblots of autophagy markers, such as ATG4B, p62, and LC3B (E) and densitometric analysis of p62 (F) and LC3B (G). Representative histological images (H) and NAFLD activity scores (I). ALT (J) and AST (K) were measured in plasma (n = 5–8 mice per group). Expression of genes involved in inflammation (Cd68, F480, Il1b, Il6, Mcp1, Nrlp3, and Tnfa), antioxidant response (Cat, Hmox1, Nrf2, Gpx, Gsr, Sod1, and Sod2), and β-oxidation (Cpt1a, Pgc1a, and Ppara) were measured by qRT-PCR and represented in volcano plots (L) (n = 3–8 mice per group). Asterisks, arrows, and arrowheads show inflammation foci, macrosteatosis, and microsteatosis vesicular, respectively. Results are displayed as means ± SEM. For statistical analyses, P values were calculated by ANOVA test (B, D, F, G, J, and K), Kruskal–Wallis test (C and I), or two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (L).

Altogether, these results indicate that four different methods of ACBP/DBI inhibition (passive neutralization with α-DBI, active autoimmunization, genetic knockout, and mutation of the ACBP/DBI receptor) similarly protect against NASH.

Transcriptional Correlates of the NASH-Preventive Effects of ACBP/DBI Inhibition.

Bulk RNA sequencing of the livers from mice receiving RCD or MCD together with IgG control or α-DBI revealed that most of the MCD-induced alterations in mRNA expression were reversed by α-DBI (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Volcano plots followed by gene ontology analyses revealed that, in the context of MCD, α-DBI downregulated multiple gene sets associated with inflammation and carcinogenesis but upregulated genes involved in fatty acid and drug metabolism as well as in peroxisomes and autophagy (SI Appendix, Figs. S3 B and C and S4A). The effects of α-DBI on the liver transcriptome of RCD-fed mice were relatively scarce compared with its effects on MCD-fed rodents (SI Appendix, Figs. S3A and S4 B and C). To validate these findings, we performed immunohistochemical detection of the macrophage marker F4/80. α-DBI prevented the increase in hepatic macrophage infiltration that is usually observed after MCD (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 D and E). Moreover, qRT-PCR analyses confirmed that α-DBI had relatively small effects on normal (RCD) livers, that MCD (compared with RCD) associates with an upregulation of multiple proinflammatory genes (Cd68, F480, Il1b, Il6, Mcp1, Nlrp3, and Tnfa) but a downregulation of antioxidant genes (Cat, Gpx, Gsr, Hmox1, Nfr2, Sod1, and Sod2), and that most (if not all) of these effects are reversed by α-DBI (SI Appendix, Fig. S3F). The anti-inflammatory effects of α-DBI were validated by measuring plasma concentrations of CCL4, CCL2 (MCP-1), CCXL10, and TNFA (SI Appendix, Fig. S5A). Moreover, the protein levels of CAT and HMOX1 were elevated in α-DBI-treated mice under MCD as compared with isotype control mice receiving the same diet, commensurate with an increased abundance of nuclear (but reduced abundance of cytosolic) NRF2 (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 B–D), which is the master transcription factor of antioxidant defense (48).

The qRT-PCR-detectable reversal of MCD-associated effects in liver mRNA expression was further corroborated when ACBP/DBI was inhibited by autoantibodies following the autoimmunization with ACBP/DBI-KLH conjugates (SI Appendix, Fig. S4D) or by tamoxifen-inducible knockout of Acbp/Dbi (SI Appendix, Fig. S4E). Mass spectrometric metabolomics revealed that MCD was coupled to a decrease in several lipid species in the liver and that this decrease was counteracted by α-DBI, as particularly evident for carnitine-conjugate fatty acids (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S6 A and B). Accordingly, MCD was coupled to a downregulation of carnitine palmitoyl transferase 1 (CPT1), the mitochondrial outer membrane transporter that is rate limiting for β-oxidation and the inhibition of which causes the depletion of acylcarnitines (49, 50). This MCD-induced downregulation of CPT1 was observed at the protein and mRNA levels and was reversed by α-DBI (Fig. 4 B and C). MCD also caused the α-DBI-repressible downregulation of Ppara (a transcription factor essential for β-oxidation) (51, 52) at the mRNA (Fig. 4D) and protein levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S5E).

In sum, ACBP/DBI inhibition close-to-fully reverses the transcriptional alterations associated with MCD-induced NASH. Of note, the genes that were significantly downregulated by ACBP/DBI neutralization in the context of MCD-triggered murine NASH significantly overlapped with genes that are upregulated in human NAFLD or NASH compared with normal livers across 10 different datasets (SI Appendix, Table S1), pointing to the translational relevance of these results.

Mechanisms of the Anti-NASH Effects of ACBP/DBI Neutralization.

To understand the contribution of autophagy to the anti-NASH effects of α-DBI, we took advantage of mice bearing a partial autophagy defect due to the constitutive knockout of Atg4b (genotype: Atg4b−/−) (53) (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C). These mice were not more susceptible to NASH induction by MCD than wild-type (WT) mice (Fig. 4 E–K). However, Atg4b−/− mice were relatively resistant to autophagy induction by α-DBI, as well as to the anti-NASH, and body weight-restoring effects of α-DBI (Fig. 4 E–K and SI Appendix, Fig. S6D). qRT-PCR analyses confirmed that, in MCD-fed WT mice, α-DBI induced antioxidant genes and downregulated proinflammatory factors as well as Acbp/Dbi mRNA (Fig. 4L and SI Appendix, Fig. S6E). These effects were much attenuated in Atg4b−/− mice (Fig. 4L), supporting the contention that autophagy is required for the transcriptional effects of ACBP/DBI neutralization.

Next, we evaluated the capacity of α-DBI to reverse (rather than to prevent) NASH by treating mice with established NASH (4 wk of MCD) by means of two injections of the mAb together with a dietary normalization to RCD (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). In this model, the MCD→RCD switch caused partial reversion (R) of NASH, and this effect was significantly enhanced by α-DBI at the histological (Fig. 5 A and B), enzymological (Fig. 5 C and D), and transcriptomic levels (Fig. 5 E–G), as well as the level of body weight recovery (SI Appendix, Fig. S7C). Moreover, α-DBI improved the recovery of carnitine species (Fig. 5 H and I), commensurate with an upregulation of CPT1A and the stimulation of autophagic flux (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 F and G).

Fig. 5.

ACBP/DBI neutralization accelerates the recovery from NASH. (A–G) α-DBI reduces hepatic damage (steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning), ameliorating recovery. Mice were fed MCD for 4 wk to induce NASH and then were fed RCD (reversion [R]) for 4 d. α-DBI or IgG was injected i.p. twice, 1 d before switch MCD to RCD and 1 d before sacrifice. Representative pictures of HES staining (A), NAFLD activity score (B), and ALT and AST transaminases activity (C and D, respectively) were analyzed in plasma (n = 3–10 mice per group). Volcano plots of genes implicated in inflammation (Cd68, F480, Il1b, Il6, and Tnfa), antioxidant response (Cat, Hmox1, Nrf2, Gpx, Gsr, Sod1, and Sod2), and β-oxidation (Cpt1a, Pgc1a, and Ppara) were measured by qRT-PCR. The comparisons between MCD IgG (n = 6) and RCD IgG (n = 5–6), R IgG (n = 7–8) and MCD IgG, and R α-DBI (n = 7–8) and R IgG are shown in E, F, and G, respectively. (H and I) Heatmap clustered by Euclidean distance (H) of changes in liver metabolite concentrations depicted as log2 FC in C57BL/6 mice injected with IgG or α-DBI (Top). All carnitines are shown in the Bottom (H) and quantified (I) (n = 12–25 mice per group). (J–N) The inhibition of autophagy or β-oxidation attenuates the beneficial effects of α-DBI in mice. Representative images of HES staining (J, K, and M) and NAFLD activity score (L and N) from several groups (n = 5–10 mice per condition). Asterisks show inflammation foci. Results are displayed as means ± SEM. Statistical analyses (P values) were performed by ANOVA test (B, C, I, and N), two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (E–G), or Kruskal–Wallis test (L).

In the next step, we determined whether inhibition of CPT1A (pharmacologically with etomoxir) and autophagy (genetically by Atg4b−/−) interferes with the beneficial effects of α-DBI on recovery from NASH (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 A and B). At the histological level, etomoxir or Atg4b knockout all attenuated the curative effects of α-DBI (Fig. 5 J–N). Of note, etomoxir failed to interfere with induction of autophagic flux by α-DBI (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 H, I, K, and L). Conversely, etomoxir-treated and Atg4b−/− mice exhibited an attenuated upregulation of Cpt1a mRNA (among other genes relevant to β-oxidation) and protein levels (SI Appendix, Fig. S7 H–M).

Altogether, these results suggest that both CPT1A and autophagy are required for the anti-NASH effects of α-DBI. Apparently, autophagy operates upstream of CPT1A because autophagy inhibition curtails α-DBI-induced CPT1A upregulation, while direct CPT1A inhibition fails to suppress α-DBI-induced autophagy.

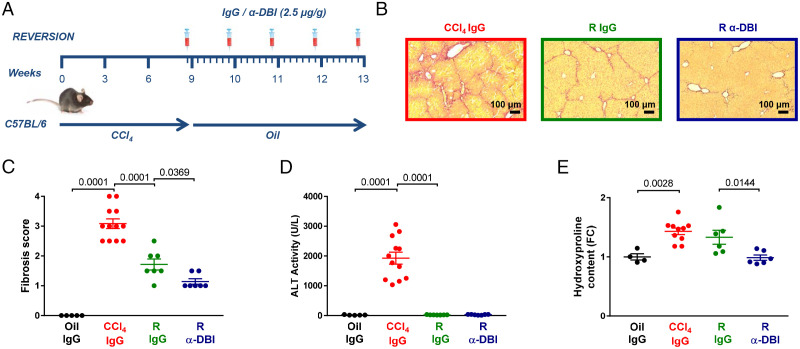

ACBP/DBI Neutralization Suppresses Fibrosis of Liver and Lung.

HFD and MCD largely fail to induce liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, which is observed when human NASH progresses (54). For this reason, we turned to a model in which liver fibrosis is induced by bile duct ligation (BLD) (55). Two weeks post-BLD, hepatic damage and fibrosis were prominent in isotype control antibody–treated mice but much attenuated after biweekly injection of α-DBI (Fig. 6 A–D). Similar results were obtained with the well-established model of carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)-induced liver fibrosis, which was modulated by weekly administration of α-DBI (or isotype IgG control for 9 wk) and/or daily injections of hydroxychloroquine (or vehicle control during the last 4 wk of the experiment) (Fig. 6E). In this model, α-DBI attenuated weight loss (SI Appendix, Fig. S8A), signs of fibrosis detectable by Sirius red staining (Fig. 6 F and G) or quantification of the collagen-enriched amino acid hydroxyproline (SI Appendix, Fig. S8B), as well as hepatic damage reflected by transaminase ALT activity (Fig. 6H and SI Appendix, Fig. S8C) and by immunoblot detection of the profibrotic markers collagen 1A1 and α-smooth muscle actin (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 D–F). The beneficial effects of α-DBI on liver damage and fibrosis were lost when autophagy was inhibited by hydroxychloroquine (Fig. 6 F–G and SI Appendix, Fig. S8 D–F). The CCl4-induced alterations in p62 and LC3-II were reversed by α-DBI, but only in the absence of hydroxychloroquine, not in its presence (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 G–I). α-DBI also reversed the CCl4-induced elevation of circulating transaminases, again only in the absence of hydroxychloroquine (Fig. 6H and SI Appendix, Fig. S8C). Moreover, α-DBI reversed most, if not all, of the transcriptional effects of chronic CCl4 intoxication, thus reducing the expression of profibrotic, proinflammatory, macrophage-associated, or transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-relevant genes but enhancing that of antioxidant enzymes. These transcriptional effects of α-DBI were abolished when hydroxychloroquine was coadministered (Fig. 6I). In a further set of experiments, we determined whether CCl4-induced liver fibrosis can be reversed more efficiently when CCl4 withdrawal is combined with weekly injections of α-DBI for 4 wk (Fig. 7A). Again, in this curative setting, α-DBI reduced damage signs of hepatic fibrosis (Fig. 7 B–E).

Fig. 6.

Neutralization of ACBP/DBI attenuates fibrosis induced by chronic liver damage. (A–D) C57BL/6 mice were subjected to bile duct ligation (BDL) for 2 wk. Mice were injected with 2.5 µg/g IgG or α-DBI i.p., 4 h and 1 h before BDL and twice per week during BDL. Representative images from hepatic Picro-Sirius Red staining (A). Fibrosis scores (B), ALT activity (C), and bilirubin levels (D) were measured (n = 5–10 mice per group). (E–I) C57BL/6 mice were injected i.p. with 2.5 µg/g α-DBI or IgG weekly and 1.6 mL/kg CCl4 twice per week for 9 wk. Additional group was treated with 50 mg/kg/day of HCQ for last 4 wk of CCl4 (E). Representative Picro-Sirius Red–stained paraffin-embedded sections (F), the quantification of fibrosis stage (G), and plasma ALT (H) are shown (n = 5–14 mice per group). Analysis of genes involved in fibrosis, inflammation (including macrophages markers), and oxidative stress. Heatmap clustered by Euclidean distance of changes in mRNA levels depicted as log2 (FC) in C57BL/6 mice injected with IgG or α-DBI plus HCQ after CCl4 (I) (n = 3–10 mice per group). Results are displayed as means ± SEM. For statistical analyses, P values were calculated by ANOVA test (B–D) or Kruskal–Wallis test (G–I).

Fig. 7.

α-DBI enhanced the recovery of liver fibrosis in an autophagy-dependent fashion. Experimental strategy for fibrosis reversion. Mice received CCl4 for 9 wk and then were treated with vehicle (oil) for 4 wk of reversion (R). We injected 2.5 μg/g IgG or α-DBI i.p. 1 d before reversion and weekly for R (A). Representative images of Picro-Sirius Red–stained paraffin-embedded sections (B), quantification of fibrosis stage (C), plasmatic ALT activity (D), and hydroxyproline levels (E) (n = 4–12 mice per group). Results are displayed as means ± SEM. For statistical analyses, P values were calculated by ANOVA test (C–E).

Altogether, these data indicate that ACBP/DBI neutralization has beneficial effects on liver fibrosis that largely depend on autophagy. Of note, in a model of bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis, α-DBI alleviated the histological signs of tissue damage while reducing upregulation of collagen-encoding genes and macrophage-associated genes (Fig. 8 A–E), supporting the contention that, beyond its hepatoprotective action, α-DBI has systemic antifibrotic effects.

Fig. 8.

ACBP/DBI neutralization attenuates lung fibrosis induced by bleomycin. Lung fibrosis was induced by intratracheal injection of one dose of 2 mg/kg bleomycin (Bleo) for 18 d in C57BL/6 mice. We injected 2.5 µg/g α-DBI or IgG each week (A). Histological section of Picro-Sirius Red/Fast Green staining (B) and damage/fibrosis Ashcroft score (C) were shown. Volcano plots of genes related with fibrosis (Acta2, Desmin, Col1a1, Col1a2, Col6a1, Col6a2, Col6a3, Pdfga, Pdgfb, Pdgfra, Pdgfrb, and Vimentin), inflammation (Cd68, F480, Il1b, Il6, Mcp1, Nrlp3, and Tnfa), and antioxidant response (Cat, Hmox1, Nrf2, Gpx, Gsr, Sod1, and Sod2) were measured by qRT-PCR. The comparisons between Bleo IgG (n = 6–7) versus Ctrl IgG (n = 3) (D) and Bleo α-DBI (n = 7–9) versus Bleo IgG (E) are represented. Results are displayed as means ± SEM. For statistical analyses, P values were calculated by Kruskal–Wallis test (C) and two-tailed unpaired Student’s t test (D and E).

Discussion

ACBP/DBI is secreted by eukaryotic cells upon induction of autophagy and then restrains autophagy by local (autocrine/paracrine) and neuroendocrine circuitries (10, 56, 57). As a result, systemic injection of a neutralizing ACBP/DBI-specific mAb (α-DBI) induces autophagy in mouse tissues including heart, liver, and lung. These effects are observed within hours and hence cannot be attributed to a reduction of food intake secondary to the blockade of orexigenic ACBP/DBI effects. We have found in the past that α-DBI reduces appetite in specific circumstances (such as after a 24-h starvation period or in HFD-induced obesity). However, α-DBI administration actually reduced the weight loss associated with MCD or chronic CCl4 intoxication yet induced autophagy in these conditions. Hence, the autophagy-stimulatory effects of α-DBI do not rely on its appetite-suppressive effects.

As mentioned in the opening text, autophagy induction has broad health-improving effects resulting from its capacity to improve cellular fitness and metabolism (2, 4–6, 8). As shown in this paper, α-DBI ameliorates ischemic tissue damage in the heart and the liver, attenuates acute hepatotoxicity of APAP and ConA, prevents and reverses MCD-induced NASH, and also displays antifibrotic activity in models of BDL or CCl4-induced liver fibrosis and bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. These beneficial effects are suppressed by high-dose hydroxychloroquine or by knockout of Atg4b (or that of Atg7 in the heart), supporting the contention that they truly depend on the induction of autophagy (Fig. 9). Mass spectrometric metabolomics indicated that the anti-NASH activity of α-DBI was accompanied by an increase in hepatic acylcarnitines, suggestive of enhanced CPT1A activity and fatty acid oxidation. Indeed, inhibition of CPT1A abolished the beneficial effect of α-DBI on NASH yet failed to interfere with autophagy induction by α-DBI. Conversely, inhibition of autophagy blocked the MCD-induced upregulation of CPT1A, suggesting that this enzyme operates downstream of autophagy to antagonize NASH.

Fig. 9.

Summary scheme of ACBP/DBI neutralization in several organs. ACBP/DBI neutralization protects against hepatic (acute, NASH, and fibrosis), heart (ischemia), and pulmonary (fibrosis) damage through autophagy activation. This protection is due to the suppression of the cell loss, inflammation, and fibrosis. The inhibition of autophagy by hydroxychloroquine treatment or Atg4b/Atg7 genetic deficiency reverts the beneficial effect of ACBP/DBI neutralization. The proposed model was created with BioRender.com.

Remarkably, α-DBI reversed most of the alterations in gene transcription associated with MCD-induced NASH in mice. A significant fraction of the α-DBI-repressed genes are associated with human NASH or NAFLD, supporting the possible clinical relevance of these results. In general, it appears that α-DBI antagonizes the NASH or liver fibrosis–associated upregulation of proinflammatory and profibrotic genes, as it prevents the downregulation of genes involved in fatty acid and drug metabolism as well as in peroxisomes and autophagy. Such gene-regulatory effects of α-DBI are largely blocked by hydroxychloroquine or Atg4b knockout, supporting the idea that they result from autophagy induction. Since α-DBI dramatically improved the histological signs of tissue damage, including local inflammation, it appears plausible that the transcriptional shifts induced by α-DBI reflect maintenance of general tissue homeostasis rather than cell-autonomous epigenetic effects of autophagy. That said, α-DBI also influenced the expression of some genes in mice under RCD, hence upregulating Ppara and downregulating Dbi. This latter phenomenon might be explained by the interruption of a feedforward loop in which ACBP/DBI induces the expression of further ACBP/DBI in the liver (58).

Close-to-total and irreversible removal of ACBP/DBI by genetic means has no detectable effects on adult mice housed under standard conditions (10). Thus, in contrast to the constitutive knockout of ACBP/DBI (59), knockout of ACBP does not compromise the skin barrier function in adult mice (35), suggesting that mAb-mediated blockade of ACBP/DBI should be well tolerated without major side effects. Accordingly, we did not detect any macroscopic or histological signs of toxicity associated with repeated α-DBI administrations. Moreover, induction of polyclonal autoantibodies capable of neutralizing ACBP/DBI failed to induce visible side effects over several months. It is remarkable, however, that the liver disease–attenuating effects of α-DBI are mimicked by those of the inducible Dbi knockout, constitutive mutation of the ACBP/DBI receptor, as well as by the induction of autoantibodies, strongly arguing in favor of the hypothesis that α-DBI acts on target rather than by recognizing additional host genome–encoded or microbial proteins that structurally resemble ACBP/DBI (60, 61).

ACBP/DBI plasma concentrations increased with age in humans (34), and knockout of its orthologs increases lifespan in yeast and nematodes (62, 63) and delays leaf senescence in plants while inducing autophagy (64). Aging is coupled to a progressive decline in autophagic flux, and genetic or pharmacological induction of autophagy extends lifespan and healthspan in model organisms, including mice (13, 15). Hence, at a speculative level, it might be attempted to neutralize ACBP/DBI to minimize the age-associated reduction in autophagy and to postpone the manifestation of age-associated diseases. This possibility should be explored in future studies.

As a general rule in pharmacology, antagonists of inhibitory pathways have fewer side effects than agonists of activating pathways. Thus, so-called immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been developed for numerous oncological indications to induce anticancer immune responses by targeting immunosuppressive surface molecules, including CTLA-4, PD-1, and PD-L1. In sharp contrast, direct immunostimulators acting on pattern-recognition receptors have largely failed in the field of immuno-oncology (65, 66). By analogy to ICIs, α-DBI, an antibody that blocks an inhibitory circuitry normally restraining autophagy, might be considered as an autophagy checkpoint inhibitor (ACI). It remains to be seen, however, whether such ACIs targeting ACBP/DBI will be developed for clinical applications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paule Opolon (Department of Pathology, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France) for histopathological analysis. We thank the core facilities of Centre de Recherche des Cordeliers and Gustave Roussy for technical support. G.K. is supported by the Ligue contre le Cancer (équipe labellisée); Agence National de la Recherche (ANR) – Projets blancs; AMMICa US23/CNRS UMS3655; Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer; Association “Ruban Rose”; Cancéropôle Ile-de-France; Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM); a donation by Elior; Equipex Onco-Pheno-Screen; European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases; Gustave Roussy Odyssea, the European Union Horizon 2020 Projects Oncobiome and Crimson (No. 101016923); Fondation Carrefour; Institut National du Cancer; Inserm (Hétérogénéité des tumeurs dans leur microenvironnement); Institut Universitaire de France; LabEx Immuno-Oncology (ANR-18-IDEX-0001); the Leducq Foundation; a Cancer Research Accelerating Scientific Platforms and Innovative Research Award from the Mark Foundation;, the Recherche Hospitalo-Universitaire Torino Lumière; Seerave Foundation; SIRIC Stratified Oncology Cell DNA Repair and Tumor Immune Elimination; and SIRIC Cancer Research and Personalized Medicine. This study contributes to the IdEx Université de Paris ANR-18-IDEX-0001. G.A. is supported by the FRM. L.S. is supported by Beatriz Galindo senior program of the Spanish Ministry of Universities; Strategic Program “Instituto de Biología y Genética Molecular (IBGM), Junta de Castilla y León” (Ref. CCVC8485); and Internationalisation Project of the “Unidad de Excelencia IBGM of Valladolid” (Ref. CL-EI-2021).

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: G.K. has been holding research contracts with Daiichi Sankyo, Eleor, Kaleido, Lytix Pharma, PharmaMar, Samsara, Sanofi, Sotio, Tollys, Vascage, and Vasculox/Tioma. G.K. is on the Board of Directors of the Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation France. G.K. is a scientific cofounder of everImmune, Samsara Therapeutics, and Therafast Bio. G.K. is the inventor of patents covering therapeutic targeting of aging, cancer, cystic fibrosis, and metabolic disorders. G.K. and O.M. are inventors of a patent covering the therapeutic use of anti-ACBP/DBI antibodies. G.K. is the founder of OsasunaTherapeutics, which targets ACBP/DBI.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2207344119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

[RNA-seq data] data have been deposited in [Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)](GSE 194346). All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

All data are included in the manuscript and SI Appendix. Additional data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus at accession No. GSE194346 (67).

References

- 1.Morishita H., Mizushima N., Diverse cellular roles of autophagy. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 35, 453–475 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz L. M., Autophagic cell death during development - Ancient and mysterious. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 656370 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kroemer G., Levine B., Autophagic cell death: The story of a misnomer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 1004–1010 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.López-Otín C., Kroemer G., Hallmarks of health. Cell 184, 33–63 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galluzzi L., Pietrocola F., Levine B., Kroemer G., Metabolic control of autophagy. Cell 159, 1263–1276 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mizushima N., Klionsky D. J., Protein turnover via autophagy: Implications for metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 27, 19–40 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deretic V., Autophagy in inflammation, infection, and immunometabolism. Immunity 54, 437–453 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galluzzi L., Yamazaki T., Kroemer G., Linking cellular stress responses to systemic homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 731–745 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levine B., Kroemer G., Biological functions of autophagy genes: A disease perspective. Cell 176, 11–42 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bravo-San Pedro J. M., et al. , Acyl-CoA-binding protein is a lipogenic factor that triggers food intake and obesity. Cell Metab. 30, 754–767.e9 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitada M., Koya D., Autophagy in metabolic disease and ageing. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 17, 647–661 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pyo J. O., et al. , Overexpression of Atg5 in mice activates autophagy and extends lifespan. Nat. Commun. 4, 2300 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fernández Á. F., et al. , Disruption of the beclin 1-BCL2 autophagy regulatory complex promotes longevity in mice. Nature 558, 136–140 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu Y. X., et al. , A TORC1-histone axis regulates chromatin organisation and non-canonical induction of autophagy to ameliorate ageing. eLife 10, e62233 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hansen M., Rubinsztein D. C., Walker D. W., Autophagy as a promoter of longevity: Insights from model organisms. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 579–593 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eisenberg T., et al. , Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nat. Med. 22, 1428–1438 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tavernarakis N., Pasparaki A., Tasdemir E., Maiuri M. C., Kroemer G., The effects of p53 on whole organism longevity are mediated by autophagy. Autophagy 4, 870–873 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meléndez A., et al. , Autophagy genes are essential for dauer development and life-span extension in C. elegans. Science 301, 1387–1391 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Madeo F., Carmona-Gutierrez D., Hofer S. J., Kroemer G., Caloric restriction mimetics against age-associated disease: Targets, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Cell Metab. 29, 592–610 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Allaire M., Rautou P. E., Codogno P., Lotersztajn S., Autophagy in liver diseases: Time for translation? J. Hepatol. 70, 985–998 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hazari Y., Bravo-San Pedro J. M., Hetz C., Galluzzi L., Kroemer G., Autophagy in hepatic adaptation to stress. J. Hepatol. 72, 183–196 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sciarretta S., Maejima Y., Zablocki D., Sadoshima J., The role of autophagy in the heart. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 80, 1–26 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Racanelli A. C., Choi A. M. K., Choi M. E., Autophagy in chronic lung disease. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 172, 135–156 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi M. E., Autophagy in kidney disease. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 82, 297–322 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klionsky D. J., et al. , Autophagy in major human diseases. EMBO J. 40, e108863 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin Z., et al. , Adiponectin protects against acetaminophen-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and acute liver injury by promoting autophagy in mice. J. Hepatol. 61, 825–831 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shen Y., et al. , Decreased hepatocyte autophagy leads to synergistic IL-1β and TNF mouse liver injury and inflammation. Hepatology 72, 595–608 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chao X., Ding W. X., Role and mechanisms of autophagy in alcohol-induced liver injury. Adv. Pharmacol. 85, 109–131 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galluzzi L., Bravo-San Pedro J. M., Levine B., Green D. R., Kroemer G., Pharmacological modulation of autophagy: Therapeutic potential and persisting obstacles. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 487–511 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dikic I., Elazar Z., Mechanism and medical implications of mammalian autophagy. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 349–364 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chiang W. C., et al. , High-throughput screens to identify autophagy inducers that function by disrupting beclin 1/Bcl-2 binding. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 2247–2260 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Capurro M. I., et al. , VacA generates a protective intracellular reservoir for Helicobacter pylori that is eliminated by activation of the lysosomal calcium channel TRPML1. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 1411–1423 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Loomis W. F., Behrens M. M., Williams M. E., Anjard C., Pregnenolone sulfate and cortisol induce secretion of acyl-CoA-binding protein and its conversion into endozepines from astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21359–21365 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Joseph A., et al. ; FACE-SZ and FACE-BD (FondaMental Academic Centers of Expertise, for Schizophrenia and for Bipolar Disorder) Groups, Metabolic and psychiatric effects of acyl coenzyme A binding protein (ACBP)/diazepam binding inhibitor (DBI). Cell Death Dis. 11, 502 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Joseph A., et al. , Effects of acyl-coenzyme A binding protein (ACBP)/diazepam-binding inhibitor (DBI) on body mass index. Cell Death Dis. 12, 599 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkatesh S., et al. , Mitochondrial LonP1 protects cardiomyocytes from ischemia/reperfusion injury in vivo. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 128, 38–50 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Motiño O., et al. , Protective role of hepatocyte cyclooxygenase-2 expression against liver ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Hepatology 70, 650–665 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Motiño O., et al. , Cyclooxygenase-2 expression in hepatocytes attenuates non-alcoholic steatohepatitis and liver fibrosis in mice. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1862, 1710–1723 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tag C. G., et al. , Bile duct ligation in mice: Induction of inflammatory liver injury and fibrosis by obstructive cholestasis. J. Vis. Exp. 96, e52438 (2015). (Journal of Visualized Experiments). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim S. N., et al. , Dose-response effects of bleomycin on inflammation and pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Toxicol. Res. 26, 217–222 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mizushima N., Yamamoto A., Matsui M., Yoshimori T., Ohsumi Y., In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1101–1111 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Haspel J., et al. , Characterization of macroautophagic flux in vivo using a leupeptin-based assay. Autophagy 7, 629–642 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki S., Toledo-Pereyra L. H., Rodriguez F. J., Cejalvo D., Neutrophil infiltration as an important factor in liver ischemia and reperfusion injury. Modulating effects of FK506 and cyclosporine. Transplantation 55, 1265–1272 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cook K. L., et al. , Hydroxychloroquine inhibits autophagy to potentiate antiestrogen responsiveness in ER+ breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 3222–3232 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shirakabe A., et al. , Evaluating mitochondrial autophagy in the mouse heart. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 92, 134–139 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montégut L., et al. , Immunization of mice with the self-peptide ACBP coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. STAR Protoc 3, 101095 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wulff P., et al. , From synapse to behavior: Rapid modulation of defined neuronal types with engineered GABAA receptors. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 923–929 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohs A., et al. , Hepatocyte-specific NRF2 activation controls fibrogenesis and carcinogenesis in steatohepatitis. J. Hepatol. 74, 638–648 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schlaepfer I. R., Joshi M., CPT1A-mediated fat oxidation, mechanisms, and therapeutic potential. Endocrinology 161, bqz046 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Serviddio G., et al. , Oxidation of hepatic carnitine palmitoyl transferase-I (CPT-I) impairs fatty acid beta-oxidation in rats fed a methionine-choline deficient diet. PLoS One 6, e24084 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Montagner A., et al. , Liver PPARα is crucial for whole-body fatty acid homeostasis and is protective against NAFLD. Gut 65, 1202–1214 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakade Y., et al. , Conophylline inhibits non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in mice. PLoS One 12, e0178436 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fernández Á. F., et al. , Autophagy couteracts weight gain, lipotoxicity and pancreatic β-cell death upon hypercaloric pro-diabetic regimens. Cell Death Dis. 8, e2970 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Powell E. E., Wong V. W. S., Rinella M., Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lancet 397, 2212–2224 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brea R., et al. , PGE2 induces apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells and attenuates liver fibrosis in mice by downregulating miR-23a-5p and miR-28a-5p. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1864, 325–337 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bravo-San Pedro J. M., et al. , Cell-autonomous, paracrine and neuroendocrine feedback regulation of autophagy by DBI/ACBP (diazepam binding inhibitor, acyl-CoA binding protein): The obesity factor. Autophagy 15, 2036–2038 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Charmpilas N., et al. , Acyl-CoA-binding protein (ACBP): A phylogenetically conserved appetite stimulator. Cell Death Dis. 11, 7 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anagnostopoulos G., et al. , Correction: An obesogenic feedforward loop involving PPARγ, acyl-CoA binding protein and GABA receptor. Cell Death Dis. 13, 1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neess D., et al. , Epidermal Acyl-CoA-binding protein is indispensable for systemic energy homeostasis. Mol. Metab. 44, 101144 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thomas A. M., Asnicar F., Kroemer G., Segata N., Genes encoding microbial acyl coenzyme A binding protein/diazepam-binding inhibitor orthologs are rare in the human gut microbiome and show no links to obesity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 87, e0047121 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neess D., Bek S., Engelsby H., Gallego S. F., Faergeman N. J., Long-chain acyl-CoA esters in metabolism and signaling: Role of acyl-CoA binding proteins. Prog. Lipid Res. 59, 1–25 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shamalnasab M., et al. , HIF-1-dependent regulation of lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans by the acyl-CoA-binding protein MAA-1. Aging (Albany NY) 9, 1745–1769 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fabrizio P., et al. , Genome-wide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies vacuolar protein sorting, autophagy, biosynthetic, and tRNA methylation genes involved in life span regulation. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001024 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xiao S., Chye M. L., The Arabidopsis thaliana ACBP3 regulates leaf senescence by modulating phospholipid metabolism and ATG8 stability. Autophagy 6, 802–804 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bejarano L., Jordāo M. J. C., Joyce J. A., Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Discov. 11, 933–959 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sharma P., Allison J. P., Immune checkpoint targeting in cancer therapy: Toward combination strategies with curative potential. Cell 161, 205–214 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Motiño O., et al. , ACBP/DBI protein neutralization confers autophagy-dependent organ protection through inhibition of cell loss, inflammation, and fibrosis. Gene Expression Omnibus. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE194346. Deposited 1 July 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

[RNA-seq data] data have been deposited in [Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO)](GSE 194346). All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

All data are included in the manuscript and SI Appendix. Additional data are available at the Gene Expression Omnibus at accession No. GSE194346 (67).