Abstract

Since ibrutinib was approved by the FDA as an effective monotherapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and multilymphoma, more and more FDA-approved covalent drugs are coming back into the market. On this occasion, the resurgence of interest in covalent drugs calls for more hit discovery techniques. However, the limited numbers of covalent libraries prevent the development of this area. Herein, we report the design of covalent DNA-encoded library (DEL) and its selection method for the discovery of covalent inhibitors for target proteins. These triazine-based covalent DELs yielded potent compounds after covalent selection against target proteins, including Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase (BTK), Janus kinase 3 (JAK3), and peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase NIMA-interacting-1 (Pin1).

Keywords: DNA encoded library, covalent library, library design, covalent inhibitors

In the middle of 20th century, covalent inhibitors were avoided due to the risks associated with an irreversible bond that can form not only with the desired target but also with off-target proteins,1,2 which may cause life-threatening side-effects. However, with the declining activity of reversible drugs and increasing chance of drug resistance, covalent drugs have come back in the pharmaceutical market. By contrast with a reversible drug, which is in the equilibrium of associating/dissociating with the target, a covalent drug can profit from nonequilibrium kinetics. This property greatly enhances the potency and target specificity of covalent drugs relative to reversible drugs; most of all, they can prolong target residence time (τ; defined as the inverse of the dissociation rate constant, koff) which is a critical factor in the clinic,3 leading to less frequent dosing and lower dosage. However, we should also keep in mind that pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics are also important determinants. Besides these advantages, in fact, some unexpected side-effects can only be triggered by the affinity-driven activity and correct orientation of the drug toward the binding pocket, which makes covalent compounds not that reactive toward other off-target biomolecules in vivo. Some novel experimental evidence including whole proteomic analytical techniques supports the concept of covalent inhibition.4,5 In fact, with increasing understanding and advancement of covalent inhibitor design, the concept of covalent inhibition in drug discovery has been substantiated by FDA-approved covalent drugs since 2000.6 Thus, the improvement of hit-discovery techniques is urgently needed.

Traditional screening methods, such as high-throughput screening or virtual screening, are usually used for reversible drug discovery; limited examples show the discovery of irreversible compounds, usually by serendipity. The false-positive results and the lack of high-quality structural information of the library are setbacks in their application. The direct covalent screening method is an efficient and rapid way of identifying covalent inhibitors. A particularly successful example is the identification of RAS G12C via a library of disulfides followed by conversion to an irreversible warhead.7 Thus, more covalent compound libraries with efficient screening methods are needed to accelerate hit discovery and the hit to lead optimization process in drug discovery.

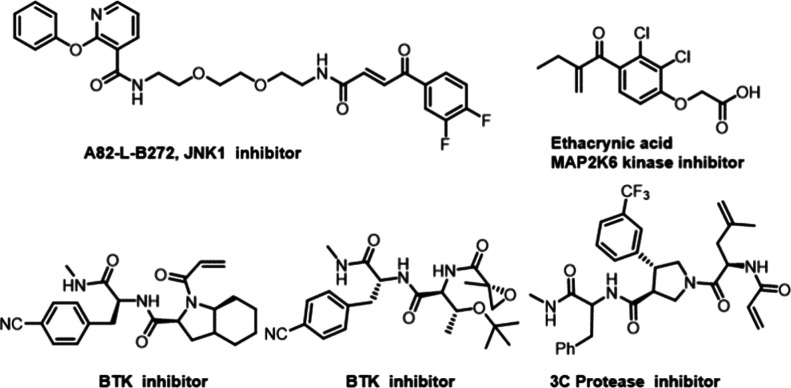

DNA-encoded library technology (DELT) provides such a platform for small molecule drug discovery through affinity binding, and it has been broadly applied in academia and industry.8 While numerous reversible binders have been discovered from DNA-encoded libraries (DELs) and progressed to clinical trial, it is in recent years that irreversible binders have been gradually discovered from DELs; see, for example, refs (9 and 10) (Figure 1). In these examples, covalent bond formation occurs at the inherent electrophilic site of these structures, and not all compounds act via covalent inhibition in the library. GSK’s report is limited to the validation of the selection method with a positive control.11 It was not until 2019 that X-Chem reported the discovery of irreversible covalent compounds of BTK from numerically large DNA-encoded chemical libraries terminated in electrophiles.12 Meanwhile, they established the selection protocol of a covalent DEL which guarantees ensuing discoveries of more covalent compounds from DELs, e.g, the discovery of covalent inhibitors for SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (3C Protease)13 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Previous irreversible inhibitors identified from DELs.

A DEL with all compounds terminated in electrophilic warhead is defined as a covalent DEL, and can go through affinity selection for covalent hit discovery. In fact, more covalent DELs are needed to meet the demand for covalent drug discovery. However, besides the two examples mentioned above, no other covalent DEL has been reported to date. Herein, we report the design of a covalent DEL with heterocycle scaffold and the selection against target proteins including BTK, JAK3, and Pin1. This scaffold provides a novel series of irreversible inhibitors with IC50 values ranging from single digital nanomole to micromole.

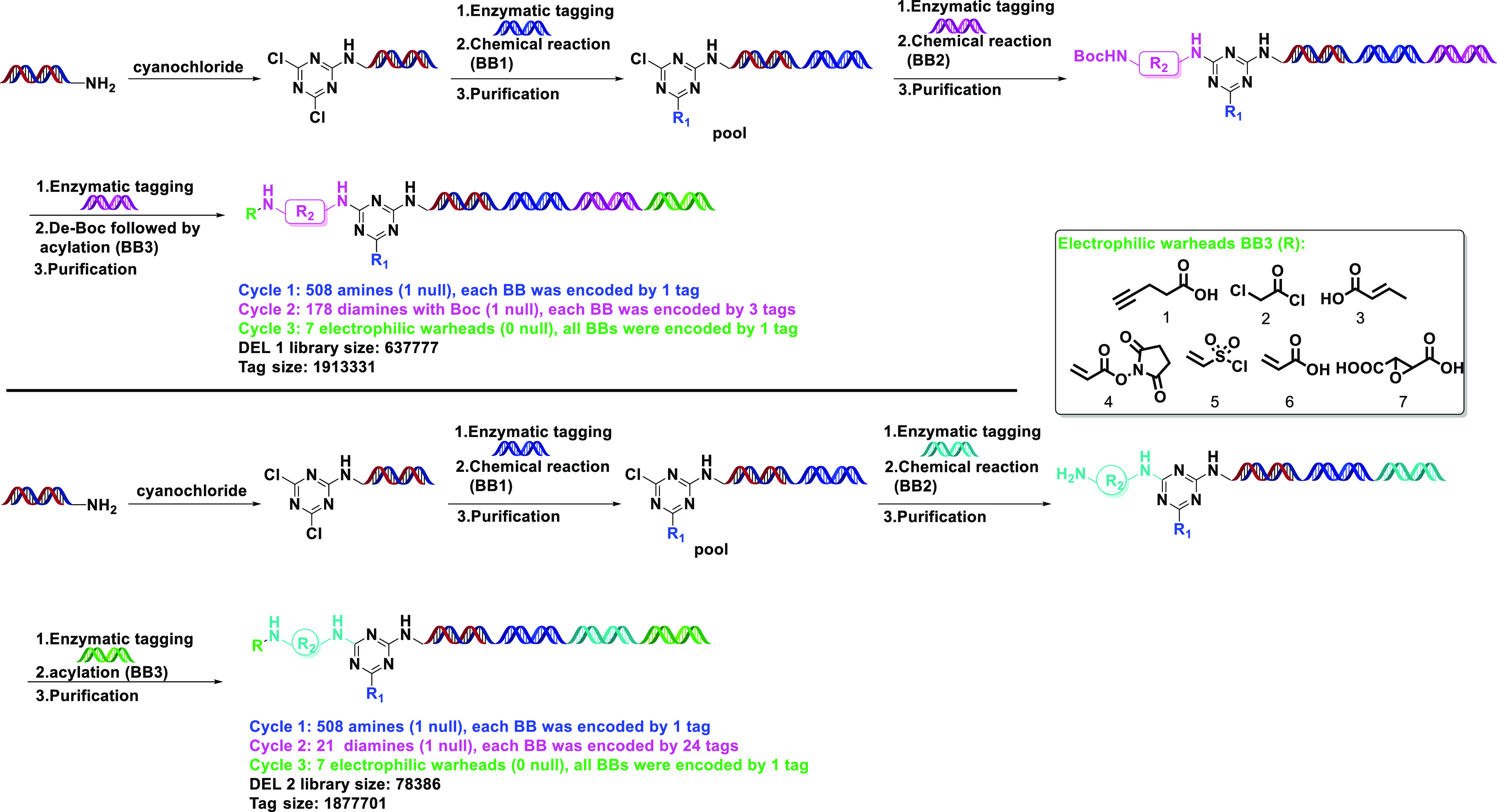

1,3,5-Triazine or s-triazine is one of the oldest organic compounds that is still being used in chemotherapeutic agents due to its pharmacological properties, such as anti-cancer, herbicidal, insecticidal, and antimicrobial activities.14 s-Triazine with multiple biological activities can introduce a more diversified DEL in structure and has been applied to DELs for reversible inhibitors previously.15,16 Due to the multiple pharmacological activities of the s-triazine scaffold, we were intrigued to see if the triazine-based DEL terminated in electrophiles could provide potent covalent inhibitors for target proteins. We synthesized a triazine-based DEL as illustrated in Scheme 1. After installation of the triazine core to the oligo, numerous amines were introduced at cycle 1 by a nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) reaction. At cycle 2, the diamine BBs are categorized into two sets, the Boc protected ones and free ones. Vigorous de-Boc conditions were likely to cause uneven oligo concentrations between the Boc protected and free amines, i.e, the concentration of the free amines would be higher than that of the protected ones in the mixture that we have confirmed in previous experiments.

Scheme 1. Construction of Triazine-Based Covalent DEL.

Thus, the triazine-based DEL was separated into two, DEL 1 with Boc protected ones and DEL 2 with free ones.

Specifically, 508 amines were incorporated, following the DNA tag installation with cyanuric chloride via SNAr reaction at cycle 1. Then, after enzymatic tagging at cycle 2, 178 Boc-diamines were employed to provide protected amine linkers with variable sizes using a similar SNAr reaction. Three different tags were used to code the same Boc-diamine BB (building block). After the de-Boc reaction,17 the fragment was conjugated with six electrophilic warheads (BB3) and one control acid in cycle 3, yielding a covalent DEL with a library size of ∼0.63 million. DEL 2 was prepared by the same procedure without a corresponding deprotection step. To supplement the diversity of linker part, we selected 20 free diamines at cycle 2 that are different from DEL 1. Therefore, we had two different DELs that are variable in cycle 2. Again, in DEL 2, 21 BBs were applied in the library synthesis with 24 different tags coded for one diamine BB. Next, we started our selection against target proteins. Referring to GSK’s method,11 we started the selection by using BTK first since the SAR (structure–activity-relationship) of covalent BTK inhibitors is well understood and provides efficient on-DNA tool compounds for DEL selection.

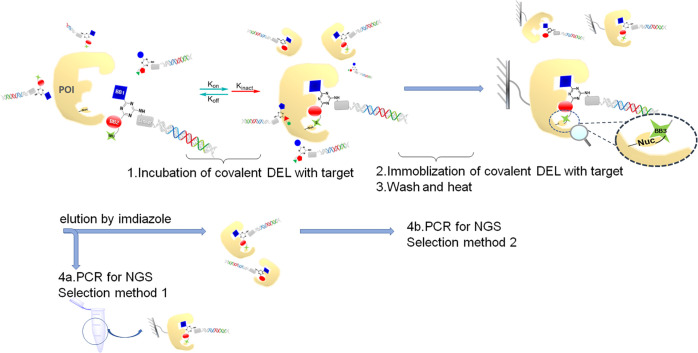

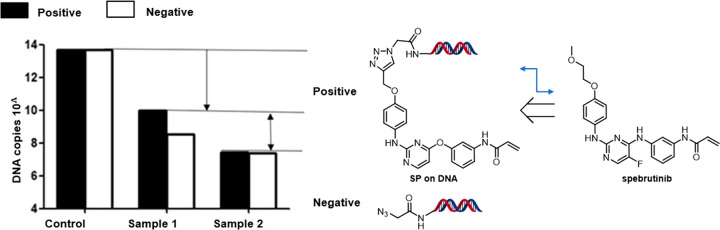

BTK is a nonreceptor Tec family tyrosine kinase that is widely expressed in hematopoietic cells and plays a critical role through the B-cell antigen receptor (BCR) and the Fcγ receptor (Fcγ R) in B cells and myeloid cells, respectively.18 BTK dysregulation is involved in numerous B derived malignancies and autoimmune diseases.19 Present BTK inhibitors have been approved by the FDA for treatment of malignant neoplasm, e.g. ibrutinib20 and spebrutinib.21 We modified spebrutinib to be used as an on-DNA tool compound (SP on-DNA compound), for which the mode-of-action is known to be via the formation of a covalent bond with the side chain of cysteine at position 481.The AOP-headpiece (see the structure in the Supporting Information (SI)) was conjugated with azide acetic acid to afford no compound on-DNA as control compound. The first selection method is as follows (Scheme 2): 1 nmol of SP on-DNA compound and 1 nmol of no compound on-DNA (or 2.5 nmol of DEL pool) were incubated with his-tagged BTK (5 μg) in selection buffer for 1 h at room temperature. Subsequently, compounds bound on BTK were captured on magnetic beads via His tag and washed in the same buffer. After stringent washing and boiling at 95 °C for denaturing, the sample was diluted in selection buffer, was labeled as sample 1, and was subjected to qPCR analysis to determine the fraction of the input of on-DNA compounds recovered in the beads. In parallel, 1 nmol of SP on-DNA compound and 1 nmol of no compound on-DNA (or 2.5 nmol of DEL pool) were incubated without target protein in selection buffer for 1 h at room temperature as negative control for assessing background binding to the beads. The negative control was dealt with the same procedure as sample 1 and labeled as sample 2. As control, 1 nmol of SP on-DNA compound and 1 nmol of no compound on-DNA (or 2.5 nmol of DEL pool) were directly subjected to qPCR as input before selection. As a result, SP on-DNA compound was recovered with more DNA copies, compared to no compound on-DNA control in sample 1. By contrast, SP on-DNA was recovered almost the same as no compound on-DNA in sample 2 (Figure 2). This result substantially confirms the selective enrichment of SP on-DNA compound on the target protein over one cycle of selection, indicating the successful setup of our covalent selection. We also tried the second selection method, which was eluting compounds from the target by imidazole (see the detailed experimental procedure in the SI). The results of these two methods are comparable, so we chose the first method as our standard protocol.

Scheme 2. Selection Procedure of Covalent DELs/on-DNA Compounds for the Discovery of Covalent Binders.

Figure 2.

qPCR analysis of BTK covalent selection. Control: the copy number of the input. Sample 1: DNA copies of positive/negative control with BTK after selection. Sample 2: DNA copies of positive/negative control without BTK after selection.

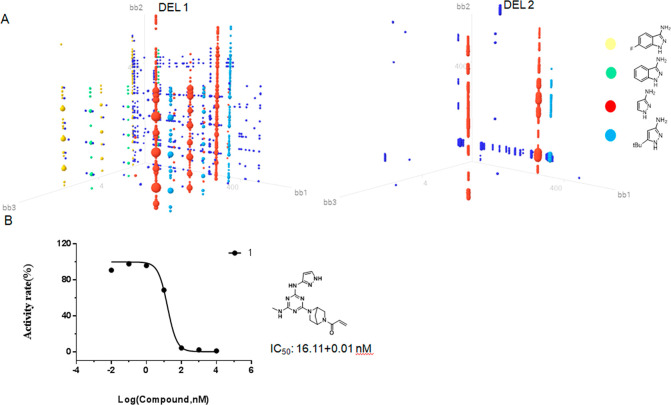

Emboldened by our initial success, we used this selection protocol with DEL 1 and 2 by still using BTK as the target. As a result, quite a lot of compounds were enriched. As shown in the 3D plot, one dot represents one on-DNA compound constructed by three cycles of BBs (Figures 3–5). The size of each dot positively correlates to the enrichment values. Structurally related BBs were enriched in cycle 1, including 1H-pyrazole-3-amine, 5-tert-butyl-1H-pyrazole-3-amine, 6-fluor-1H-pyrazole-3-amine, and 1H-indazol-3-amine (Figure 3). BBs at cycle 2 include a wide variety of different diamines, indicating they are interchangeable at this cycle. Acrylamide was slightly preferred compared to chloroacetyl chloride at cycle 3 of DEL 1, while chloroacetyl chloride was most highly enriched at cycle 3 of DEL 2 (see the detailed enrichment in Table S1). Synthesis of the most highly coenriched BBs in DEL 1 yielded compound 1 with the fold-enrichment value of 837. Compound 1 was determined to have an IC50 value of 16 nM by using a homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence assay (HTRF). This result greatly encouraged us, since we successfully discovered BTK inhibitors from a 637777-membered covalent library.

Figure 3.

(A) Output data analysis of DEL 1 and DEL 2 after selection against BTK. The three axes labeled as bb1, bb2, and bb3 represent building blocks in cycles 1, 2, and 3. Each cluster circled in different colors represents one enriched BB in cycle 1. (B) Biochemical activity of compound 1.

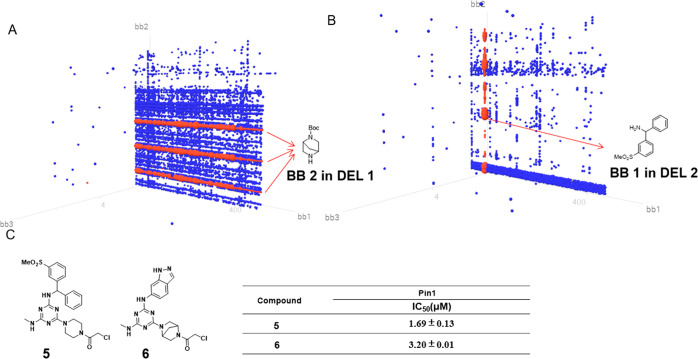

Figure 5.

(A) Output data analysis of DEL1 after selection against Pin1. (B) Output data analysis of DEL 2 after selection against Pin1. (C) Biochemical activity of compounds 5 and 6.

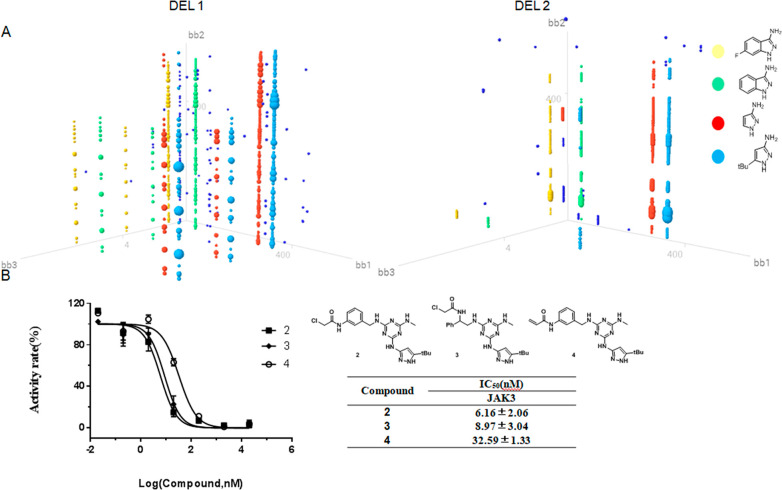

Janus kinase 3 (JAK3) is the second target we choose and is structurally and functionally related to BTK.22 JAK3 is a cytoplasmic tyrosine kinase protein that is implicated in cell signaling processes and plays a significant role in cancer as well as autoimmune and inflammatory diseases.23 After the selection against JAK3, the output analysis data revealed the same set of enriched features in cycle 1 as shown in BTK, including 5-tert-butyl-1H-pyrazole-3-amine, 1H-pyrazole-3-amine, 6-fluor-1H-pyrazole-3-amine, and 1H-indazol-3-amine at cycle 1. A range of cyclic and linear aliphatic diamines were tolerated at cycle 2. A small difference was at cycle 3, where chloroacetyl chloride was much more favored than acrylamide. Synthesis of the most highly coenriched BBs yielded compounds 2 and 3. The observed fold-enrichment values for these two compounds were 516 and 632, respectively. Given the selected features at cycle 3, the electrophile of compound 2 was replaced with acrylamide, leading to compound 4 with a fold-enrichment value of 236 in DEL 1, to assess the correlation of enrichment values and potency. Consequently, compounds 2 and 3 exhibited single digital nanomolar IC50 values, and 4 has an IC50 of 32 nM (Figure 4). In all, the screening against BTK and JAK3 indicates the indispensable role of pyrazole at cycle 1. Since BTK and JAK3 have similar SAR profiles, we tested the cross-activity of compounds 1–4 for BTK and JAK3 (Table 1). As expected, compound 1 showed moderate activity for JAK3; the activity is about 40 times less potent than that for BTK. Similarly, the activities of compounds 2–4 for BTK are 6–118 times less potent than that for JAK3.

Figure 4.

A. Output data analysis of DEL 1 and 2 after selection against JAK3. The x, y and z axes labeled as bb1, bb2, bb3 represent building blocks in cycle 1, 2, 3. Each cluster circled in different color represents one enriched structure in cycle 1. B. Biochemical activity of compounds 2-4.

Table 1. Cross-activity of 1–4 against BTK and JAK3.

| IC50 (nM) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Compound | BTK | JAK3 |

| 1 | 16.11 ± 0.01 | 698.80 ± 129.26 |

| 2 | 98.28 ± 0.64 | 6.16 ± 2.06 |

| 3 | 1898.50 ± 94.05 | 8.97 ± 3.04 |

| 4 | 637.75 ± 84.64 | 32.59 ± 1.33 |

The activities of compounds 1–4 are positively correlated to the enrichment values of these compounds in the DEL, indicating our covalent selection is distinguishable against individual targets although structurally related targets may get a similar profile of enrichment, as shown in the data of BTK and JAK3.

To validate the MOA (mechanism of action) of 1–4, we synthesized truncated compounds without electrophilic warheads (Figure S5A). Unsurprisingly, the activity of these compounds decreased significantly, compared to final compounds 1–4 (Table 1). Additionally, we incubated compound 1 with BTK, and the compound 1 pretreated BTK sample was digested with trypsin and subjected to mass spectroscopy. As a result, compound 1 showed 100% covalent labeling of the peptide sequence containing residue C481 after trypsin digestion, indicating the unique covalent labeling of C481 (Table S4 and Figure S8).

Peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase NIMA-interacting 1 (Pin1) is a common regulator in diverse physiological processes.24 It specifically isomerizes phosphorylated Ser/Thr-Pro peptide bonds in a variety of proteins. Pin1, due to its diverse functions in the cell cycle and its implication in numerous diseases, especially human cancers,25 has been studied as a potential druggable target. A recent study showed the overexpression of Pin1 in cancer cells and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) correlates with poor survival in PDAC (pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma) patients.26 Pin1 drives the desmoplastic and immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) by acting on CAFs and induces lysosomal degradation of the PD-1 ligand PD-L1 and the gemcitabine transporter ENT1 in cancer cells besides activating multiple cancer pathways. The report substantiates Pin1 as a druggable target in the clinic.

Thus, targeting Pin1 by small molecules can block multiple cancer pathways, rendering PDAC eradicable by immune chemotherapy. Previous non-peptidyl inhibitor design often resulted in compromising activity due to the narrow, shallow pocket of its catalytic domain.27 The nucleophilic residue (Cystein113) located in the active site of the C-terminal PPIase domain of Pin1 enables covalent inhibitor design, which can greatly enhance the potency of Pin1 inhibitors.28,29 For our strategy, we utilized our triazine-based DELs to seek hits of Pin1 for further lead optimization, demonstrating the screening diversity of our DELs for both kinase and non-kinase targets. The selection against Pin1 was done as previously described; the output analysis is shown in Figure 5. While DEL 1 and 2 gave similar structural profiles for BTK and JAK3, they afford a different enrichment profile for Pin1. The most highly enriched BB in DEL 1 was at cycle 2, where different tags encoding one diamine were all enriched, tolerating a broad range of aromatic amines at cycle 1. In contrast to DEL 1, cycle 1 in DEL 2 showed a clear SAR: (3-(methylsulfonyl)phenyl)-(phenyl)methanamine is highly enriched at this cycle, tolerating several clusters of diamines at cycle 2. Both DEL 1 and 2 provide chloroacetyl chloride as the only selected BB at cycle 3 (see detailed enrichment in Table S3).

We synthesized off-DNA compounds 5 and 6 from DEL 1 and 2, respectively. The truncated compounds without electrophile (BB3) were also synthesized. While compounds 5 and 6 gave signal digital micromole IC50 values (Figure 5), the IC50 values of the control compounds without electrophiles were more than 100 μM (Figure S7). Thus, the result further validated that Pin1 compounds act via covalent inhibition. The difference in activity between BTK&JAK3 and Pin1 can be comprehensible when referring to the natural ligands of these active sites. BTK and JAK3 inhibitors occupy the ATP binding pocket; the triazine scaffold can, to a large extent, resemble the ATP structure by acting like a pyrimidine derivative and captures most of the key interactions as ATP does. However, for Pin1, the active site accommodates a linear peptide substrate; the triazine scaffold in a branched geometry can only partly insert into the active site, which decreases the potency.

In summary, traditional organic chemistry produced numerous compounds with interesting pharmacological properties. Techniques for transformation of these compounds into chemotherapeutic agents are always popular themes in drug discovery area. Scientists have developed technologies to deliver organic compounds to their right biological targets, such as high-throughput screening or virtue screening. However, they often require sufficiently large libraries with high diversity and highly qualified, sensitive biochemical assays. DELT emerged in the 90s as a hit-discovery tool for drug discovery.30 Although DEL affinity selection for reversible inhibitors has been used for several decades, DEL affinity selection for irreversible inhibitors is far from maturation. It needs to be refined and explored more. As previously reported, s-triazine is widely used in medicinal chemistry due to its multiple biological functions in vivo. Intrigued by its application in DELs, we designed a triazine-based covalent DEL for discovery of irreversible inhibitors of target proteins. The 637777 and 78386 membered libraries produced a novel series of inhibitors of BTK, JAK3, and Pin1 with moderate to strong potency.

Our efforts on discovering irreversible inhibitors from a DEL leads to many promising candidate compounds for hit to lead optimization. Thus, the triazine DEL provides such a powerful link converting traditional triazine chemistry to the application of chemotherapeutic agents for different targets. Further studies about other targets are underway in our lab and will be published in the near future.

Acknowledgments

Jia Li gratefully appreciates NSFC-81821005 and the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (18431907100, 19430750100) for financial support of this work. Xiaojie Lu gratefully appreciates NSFC-91953203, NSFC-21877117, NSFC-81972563, and Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project for financial support of this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CLL

chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- DEL

DNA-encoded library

- BTK

Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase

- JAK3

the Janus kinase 3

- Pin1

peptidyl-prolyl cis/trans isomerase NIMA-interacting-1

- DELT

DNA-encoded library technology

- 3C Protease

3-chymotrypsin-like protease

- SNAr

nucleophilic aromatic substitution

- BB

building block

- SAR

structure–activity-relationship

- BCR

B-cell antigen receptor

- FcγR

Fcγ receptor

- AOP

Fmoc-15-amino-4,7,10,13-tetraoxapentadecanoic acid

- HTRF

homogeneous time-resolved assay

- MOA

mechanism of action

- CAFs

cancer-associated fibroblasts

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- TME

tumor microenvironment

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmedchemlett.2c00127.

Author Contributions

† Linjie Li, Mingbo Su, Weiwei Lu, and Hongzhi Song contributed equally. LinJie Li implemented the sample preparation, data analysis, and manuscript writing. Mingbo Su finished the biochemical assays of BTK and JAK3. Weiwei Lu finished DEL the affinity selection and manuscript revision. Hongzhi Song finished the biochemical assay of Pin1. Jiaxiang Liu synthesized the covalent DEL. Xin Wen, Yanrui Suo, Jingjing Qi, Xiaomin Luo, and Yu-Bo Zhou helped with manuscript revision and data organization. Xin-Hua Liao and Jia Li are the supervisors of our collaborators. Xiaojie Lu is the corresponding author and supervised the whole project.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Bauer R. A. inhibitors in drug discovery: from accidental discoveries to avoided liabilities and designedtherapies. Drug Discovery Today. 2015, 20, 1061–1073. 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillie T. A. Drug–protein adducts: past, present, and future. Med. Chem. Res. 2020, 29, 1093–1104. 10.1007/s00044-020-02567-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland R. A.; Pompliano D. L.; Meek T. D. Drug-Target Residence Time and Its Implications for Lead Optimization. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006, 5, 730–739. 10.1038/nrd2082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortenson D. E.; Brighty G. J.; Plate L.; Bare G.; Chen W.; Li S.; Wang H.; Cravatt B. F.; Forli S.; Powers E. T.; Sharpless K. B.; Wilson I. A.; Kelly J. W. ‘Inverse drug discovery’ strategy to identify proteins that are targeted by latent electrophiles asexemplified by aryl fluorosulfates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 200–210. 10.1021/jacs.7b08366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Backus K. M.; Correia B. E.; Lum K. M.; Forli S.; Horning B. D.; Gonzalez-Paez G. E.; Chatterjee S.; Lanning B. R.; Teijaro J. R.; Olson A. J.; Wolan D. W.; Cravatt B. F. Proteome-wide covalent ligand discovery in native biological systems. Nature 2016, 534, 570–574. 10.1038/nature18002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vita E. 10 years into the resurgence of covalent drugs. Future Med. Chem. 2021, 13, 193–210. 10.4155/fmc-2020-0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostrem J. M.; Peters U.; Sos M. L.; Wells J. A.; Shokat K. M. K-Ras(G12C) inhibitors allosterically control GTP affinity and effector interactions. Nature. 2013, 503, 548–551. 10.1038/nature12796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald P. R.; Paegel B. M. DNA-Encoded Chemistry: Drug Discovery from a Few Good Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 7155–7177. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann G.; Rieder U.; Bajic D.; Vanetti S.; Chaikuad A.; Knapp S.; Scheuermann J.; Mattarella M.; Neri D. A specific and covalent JNK-1 ligand selected from an Encoded Self-Assembling Chemical Library. Chem.—Eur. J. 2017, 23, 8152–8155. 10.1002/chem.201701644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A. I.; McGregor L. M.; Jain T.; Liu D. R. Discovery of a covalent kinase Inhibitor from a DNA-Encoded Small-Molecule Library x Protein Library Selection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 10192–10195. 10.1021/jacs.7b04880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Z.; Grady L. C.; Ding Y.; Lind K. E.; Davie C. P.; Phelps C. B.; Evindar G. Development of a selection method for discovering irreversible (covalent) binders from a DNA-Encoded Library. SLAS Discovery 2019, 24, 169–174. 10.1177/2472555218808454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilinger J. P.; Archna A.; Augustin M.; Bergmann A.; Centrella P. A.; Clark M. A.; Cuozzo J. W.; Dather M.; Guie M. A.; Habeshian S.; Kiefersauer R.; Krapp S.; Lammens A.; Lercher L.; Liu J.; Liu Y.; Maskos K.; Mrosek M.; Pflugler K.; Siegert M.; Thomson H. A.; Tian X.; Zhang Y.; Konz Makino D. L.; Keefe A. D. Novel irreversible covalent BTK inhibitors discovered using DNA-encoded chemistry. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 42, 116223–116238. 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge R.; Shen Z.; Yin J.; Chen W.; Zhang Q.; An Y.; Tang D.; Satz A. L.; Su W.; Kuai L. Discovery of SARS-CoV-2 main protease covalent inhibitors from a DNA-encoded library selection. SLAS Discovery 2022, 27, 79–85. 10.1016/j.slasd.2022.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D. R.; Modh R. P.; Chikhalia K. H. Privileged s-triazines: structure and pharmacological applications. Future Med. Chem. 2014, 6, 463–477. 10.4155/fmc.13.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.; O’Keefe H.; DeLorey J. L.; Israel D. I.; Messer J. A.; Chiu C. H.; Skinner S. R.; Matico R. E.; Murray-Thompson M. F.; Li F.; Clark M. A.; Cuozzo J. W.; Arico-Muendel C.; Morgan B. A. Discovery of potent and selective inhibitors for ADAMTS-4 through DNA-Encoded Library Technology (ELT). ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 888–893. 10.1021/acsmedchemlett.5b00138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.; Belyanskaya S.; DeLorey J. L.; Messer J. A.; Joseph Franklin G.; Centrella P. A.; Morgan B. A.; Clark M. A.; Skinner S. R.; Dodson J. W.; Li P.; Marino J. P. Jr.; Israel D. I. Discovery of soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors through DNA-encoded library technology (ELT). Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 41, 116216–116224. 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franch T.; Lundorf M. D.; Jacobsen S. N.; Olsen E. K.; Andersen A. L.; Holtmann A.; Hansen A. H.; Sorensen A. M.; Goldbech A.; De Leon D.; Kaldor D. K.; Slok F. A.; Husemoen G. N.; Dolberg J.; Jensen K. B.; Petersen L.; Nørregaard-Madsen M.; Godskesen M. A.; Glad S. S.; Neve S.; Thisted T.; Kronborg T. A.; Sams C.; Felding J.; Freskgaard P.-O.; Gouliaev A. H.; Pedersen H.. Enzymatic encoding methods for efficient synthesis of large libraries. Patent Application WO2007/062664A2, 2007.

- Mohamed A. J.; Yu L.; Bäckesjő C.-M.; Vargas L.; Faryal R.; Aints A.; Christensson B.; Berglo A.; Vihinen M.; Nore B. F.; Edvard Smith C. I. Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (Btk): function, regulation, and transformation with special emphasis on the PH domain. Immunol. Rev. 2009, 228, 58–73. 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukada S.; Rawlings D. J.; Witte O. N. Role of Bruton’s tyrosine kinase in immune deficiency. Curr. OpinI. mmunol. 1994, 6, 623–630. 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90151-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan W. N. Regulation of B lymphocyte development and activationby Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase. Immunol.Res. 2001, 23, 147–156. 10.1385/IR:23:2-3:147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziouti F.; Rummler M.; Steyn B.; Thiele T.; Seliger A.; Duda G. N.; Bogen B.; Willie B. M.; Jundt F. Prevention of bone destruction by mechanical loading is not enhanced by the Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitor CC-292 in myeloma bone disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3840–3853. 10.3390/ijms22083840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzeni F.; Talotta R.; Nucera V.; Marino F.; Gerratana E.; Sangari D.; Masala I. F.; Sarzi-Puttini P. Adverse events, clinical considerationsand management recommendations in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with JAK inhibitors. Expert. Rev.Clin.Immunol. 2018, 14, 945–956. 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1504678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pery N.; Ijaz F.; Rizvi N. B.; Munawar M. A.; Shafiq M. I. Dual Targeting of Janus Kinase and Bruton’s Tyrosine Kinase: A New Approach to Control the Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Pakistan J. Zool. 2020, 53, 281–293. 10.17582/journal.pjz/20191010081058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C. W.; Tse E. PIN1 in cell cycle control and cancer. Front. Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1367–1376. 10.3389/fphar.2018.01367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.; Wu Y. R.; Yang H. Y.; Li X. Z.; Jie M. M.; Hu C. J.; Wu Y. Y.; Yang S. M.; Yang Y. B. Prolyl isomerase Pin1: a promoter of cancer and a target for therapy. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 883–899. 10.1038/s41419-018-0844-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koikawa K.; Kibe S.; Suizu F.; Sekino N.; Kim N.; Manz T. D.; Pinch B. J.; Akshinthala D.; Verma A.; Gaglia G.; Nezu Y.; Ke S.; Qiu C.; Ohuchida K.; Oda Y.; Lee T. H.; Wegiel B.; Clohessy J. G.; London N.; Santagata S.; Wulf G. M.; Hidalgo M.; Muthuswamy S. K.; Nakamura M.; Gray N. S.; Zhou X. Z.; Lu K. P. Targeting Pin1 renders pancreatic cancer eradicable by synergizing with immunochemotherapy. Cell. 2021, 184, 4753–4771. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du L.; Wang X.; Cui G.; Xu B. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel thiazole-based derivatives as human Pin1 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 29, 115878–115891. 10.1016/j.bmc.2020.115878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campaner E.; Rustighi A.; Zannini A.; Cristiani A.; Piazza S.; Ciani Y.; Kalid O.; Golan G.; Baloglu E.; Shacham S.; Valsasina B.; Cucchi U.; Pippione A. C.; Lolli M. L.; Giabbai B.; Storici P.; Carloni P.; Rossetti G.; Benvenuti F.; Bello E.; D’Incalci M.; Cappuzzello E.; Rosato A.; Del Sal G. A covalent PIN1 inhibitor selectively targets cancer cells by a dual mechanism of action. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15772–15786. 10.1038/ncomms15772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubiella C.; Pinch B. J.; Koikawa K.; Zaidman D.; Poon E.; Manz T. D.; Nabet B.; He S.; Resnick E.; Rogel A.; Langer E. M.; Daniel C. J.; Seo H. S.; Chen Y.; Adelmant G.; Sharifzadeh S.; Ficarro S. B.; Jamin Y.; Martins da Costa B.; Zimmerman M. W.; Lian X.; Kibe S.; Kozono S.; Doctor Z. M.; Browne C. M.; Yang A.; Stoler-Barak L.; Shah R. B.; Vangos N. E.; Geffken E. A.; Oren R.; Koide E.; Sidi S.; Shulman Z.; Wang C.; Marto J. A.; Dhe-Paganon S.; Look T.; Zhou X. Z.; Lu K. P.; Sears R. C.; Chesler L.; Gray N. S.; London N. Sulfopin is a covalent inhibitor of Pin1 that blocks Myc-driven tumors in vivo. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 954–963. 10.1038/s41589-021-00786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner S.; Lerner R. A. Encoded combinatorial chemistry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 5381–5383. 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.