Abstract

The microbiome plays essential roles in health and disease. Our understanding of the imbalances that can arise in the microbiome and their consequences is held back by a lack of technologies that selectively knock out members of these microbial communities. Antibiotics and fecal transplants, the existing methods for manipulating the microbiota of the gastrointestinal tract, are not sufficiently pinpointed to reveal how particular microbial genes, strains, or species affect human health. A toolset for the precise manipulation of the microbiome could significantly advance disease diagnosis and treatment. Here, we provide an overview of current and future strategies for the development of molecular tools that can be used to probe the microbiome without producing off-target effects.

Introduction

The microbial communities of the human microbiota shape nutrition, immunity, metabolism, and the nervous system [1] [–] [3]. The Human Microbiome Project (https://hmpdacc.org/) initiated an overarching attempt to understand the significance and prevalence of microbiota-mediated disease. We now know that problems arise when the balance among various microbial members is thrown off. Indeed, some of the world’s most prevalent diseases can be traced to altered ratios or other changes in the composition of the microbiota. For example, altered ratios between Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes, two of the major bacterial phyla represented in the human microbiome, have been linked to obesity [4]. Similarly, an increase in Bacteroidetes and Clostridium has been associated with diabetes [4], and an indigenous murine gut microbiota has been linked to a model of Parkinson’s disease (germ-free mice do not manifest the disease). The microbiome is also thought to be involved in autoimmune disorders (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease [5]), atopic dermatitis [6,7], psoriasis [8,9], cardiovascular disease [10], colon cancer [10], rheumatoid arthritis [10], major depression [10], and neurological disorders [10].

What we know about the impact of the microbiota on these disease states is mostly limited to the phylum level; the specific bacterial determinants, at the species level or strain level, remain underexplored. This gap in our knowledge is a barrier to finding new diagnostic methods and treatments. However, despite this being a young field of research, correlations between select bacteria and disease have been established. These include enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis, which produces B. fragilis toxin (BFT) that has been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), acute diarrhea, and colorectal cancer [11]. The commensal bacterium Akkermansia muciniphila has also been linked with gut disorders, with its relative abundance being inversely correlated with metabolic disorders including IBD, obesity, and colorectal cancer [12,13].

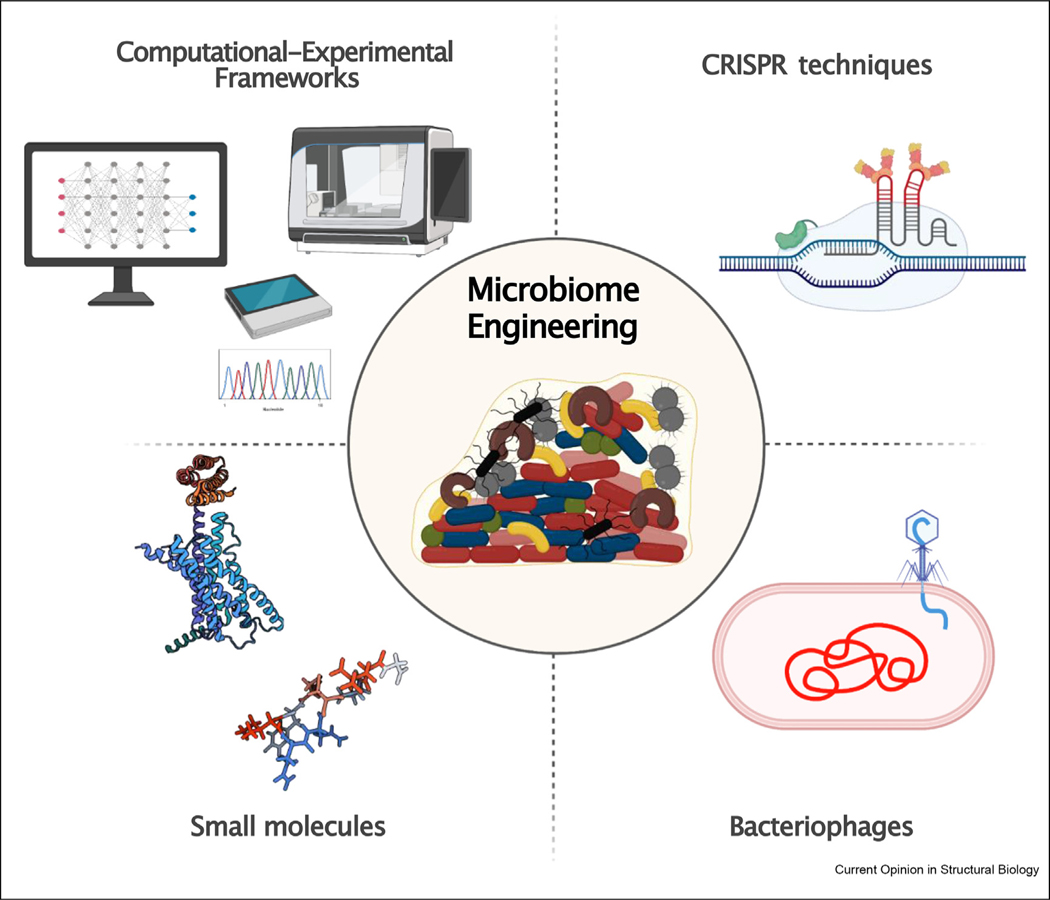

Many approaches exist for microbiota modulation: leveraging diet [14], fecal microbiome transplantation [15], the use of known antibiotics [16], the use of probiotics [17], engineered bacteria that express biosynthetic pathways [18,19], the use of gnotobiotic mouse models colonized with defined microbial consortia [20], and metagenomic studies for harnessing the small molecules produced by the microbiome itself [21]. These approaches are primarily broad-spectrum and thus do not target individual bacterial strains. Currently we do not have tools that target specific microbiota species within larger microbial communities. Yet, highly selective, microbiota-targeting tools are critical not only for studying disease-causing mechanisms but also for ultimately serving as therapies themselves, once it is known which specific bacteria are implicated in the disease. Despite several prior attempts [22] to modulate microbiota communities, to date there are no tools that can precisely knock out selected bacteria. Here, we provide an overview of approaches that can be developed to reprogram the microbiome (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic of the current tools available for probing the microbiome.

Computational techniques coupled with efficient high-throughput experimental platforms are being used for the targeted engineering of microbiome communities. Advances in synthetic biology have enabled CRISPR and engineered bacteriophages to be used as targeted molecular tools capable of reconfiguring bacterial communities. Recent reports have also revealed that small molecules, such as proteins and peptides, possess selective activity towards certain bacterial genera and species, opening up numerous opportunities for ways to sculpt the microbiome.

Molecular tools and techniques available

Discovery of molecular tools for microbiome engineering

Designing effective antimicrobial compounds requires detailed knowledge of their microbial targets, such as specific binding sites, proteins, intracellular molecules, and membrane components. High-throughput techniques for screening compounds have been widely used to assess, experimentally and computationally, the efficacy of known drugs as microbiome-targeting anti-microbials. Integrated multi-omics analyses can accelerate the discovery of potentially active compounds. Multi-omics was used to discover single medications, and their combinations, that can shift both the metabolome and microbiome towards a healthier state in patients with cardiometabolic diseases [16]. For instance, combinations of antibiotics synergistically reduced serum atherogenic lipoproteins and intestinal Roseburia, a genus within the Firmicute phylum, was enriched by diuretic agents when combined with β-blockers. Several of the antibiotics analyzed in the study exhibited a relationship between the number of courses prescribed and a microbiome associated with greater cardiometabolic disease severity. The use of a computational framework made it possible to correlate microbiome composition, cardiometabolic drug dosage, and improvement in important clinical markers. The results shed light on the effects of certain drugs and disease on the microbiome of over-medicated individuals [16].

Metagenomic and large-scale genomic analyses have also been explored as tools to find microbiome-targeting molecules. These strategies combine computational and experimental techniques to discover and characterize molecules from complex datasets that potentially have useful activity (e.g., the sum total of genomic data from the human microbiome). Recently, a metagenomic strategy was used to mine bacterial genomes in 3203 samples for small-molecules encoded in biosynthetic gene clusters. The findings enabled the discovery of a clinically relevant class of molecules, the type II polyketides, which are widely encoded by organisms present in the human microbiome. Type II polyketides resemble clinically used polyketides in structure and biological activity [21]. Peptides from 1773 human-associated metagenomes from different body regions for the detection of peptides with antimicrobial activity. More than 4500 conserved families of peptides were identified, of which 30% were characterized as being part of secreted or transmembrane proteins. This finding indicated that the peptides might encounter bacteria outside the cells in which they are produced. The study indicated that the genes encoding some of these peptides are transferred horizontally and that the peptides are part of putative housekeeping, defense-related, and mammalian-specific proteins. Thus, these families of peptides found in the human microbiome may perform diverse and previously unreported functions [22] that may affect the community of the producer strains. Large-scale analyses have also been used to mine the human proteome for potential antimicrobial peptides hidden in the human proteome [23]. Large-scale metagenomic analysis can be applied to other types of small molecules and be used to unveil interesting chemistries in the human microbiome. Such information is useful for studying interbacterial interactions within the microbiome and may point to drug discovery.

High-throughput screens of known antibiotics have been conducted to identify agents that selectively target human gut microbiome species [24,25]. In these studies, different antibiotic classes were shown to exhibit distinct inhibition spectra, including generation dependence and phylogeny independence for quinolones and β-lactams, respectively. Antimicrobials that kill bacteria by inhibiting protein synthesis, such as macrolides and tetracyclines, were active against most gut commensals tested. The species-specific killing activity was also independent of the killing mechanism of the antibiotic, bactericidal or bacteriostatic. These findings highlight the diverse ways antibiotics affect the gut microbiota and point to future strategies aimed at circumventing such adverse effects.

CRISPR-based technologies

CRISPR-based technologies have shown some efficacy at removing specific kinds of bacteria, including microbiota members [26], by targeting select sequences of DNA. Although these technologies are limited by the need of a delivery vehicle (e.g., bacteriophages), low efficacy, deleterious off-target effects, and the rapid development of bacterial resistance due to selective evolutionary pressure, they are, nevertheless, useful in certain circumstances. For example, a strategy to edit the genomes of specific gut microbes within communities was recently characterized and validated. Environmental transformation sequencing, a technique consisting of transposon insertions that are delivered, mapped, and quantified in microbial communities, demonstrated that microbial communities can be manipulated (Figure 2a). Manipulation can occur at the level of the organism or the genetic locus, by all-in-one RNA-guided CRISPR-Cas transposase systems. This proof-of-concept study was then validated by targeted DNA insertion into the identified organisms in soil and infant gut microbiota samples, to produce species-specific and site-specific genomic edits [27].

Figure 2. Molecular tools for sculpting the microbiome.

(a) Identification of bacterial targets by CRISPR enable probing the gut microbiome [27,28]. (b) Bacteriophages have been engineered ex vivo for the manipulation of bacterial communities in the gut [34,35]. (c) Stable peptides have been used to selectively target oral bacteria by interacting with specific bacterial components [42,43].

There have also been reports of the use of engineered probiotics to deliver CRISPR-Cas systems to eliminate drug-resistant bacteria present within a microbiome environment [28]. For example, accelerated laboratory evolution was used to optimize the transfer efficiency of conjugative plasmid TP114. In this study, a single dose of this conjugative delivery vehicle for CRISPR-Cas9 eliminated >99.9% of its target pathogen (Escherichia coli) in the murine gut. This system was then applied to a Citrobacter rodentium infection model, achieving full pathogen clearance from the endogenous microbiome after four consecutive days of treatment.

The specificity of CRISPR-based technologies and the advances in the field have enabled the initial steps towards understanding the microbiome environment and how microbiome members interact. Indeed, CRISPR-based technologies have paved the way for the precise modulation of microbiome communities. However, studies are still preliminary, and we are far from obtaining treatments for human diseases or re-setting the balance in the microbiome. Alternatively, there are well-established approaches to reconfigure gut microbial communities. These include metagenomic alteration of gut microbiome by in situ conjugation (MAGIC), a platform for the identification and modification of genetically tractable microbiota [29]. MAGIC consists of a suite of mobile plasmids (pGT) containing replicative origins with a range of host ranges (from narrow to broad), an RP4 transfer origin, a selection marker, and the desired payload. The same approach was also used to deliver integrative payloads through the use of the Himar transposon system. This in situ approach shows that novel genetic capabilities can be introduced into a range of taxa from the mammalian gut microbiome.

Bacteriophages (phages)

An alternative approach for investigating the microbiome is the use of engineered bacteriophages, enabling in situ modification of the microbial ecosystem [30]. As natural components of the human microbiome, phages co-colonize the human microbiome along with their bacterial hosts. The most common approach for using phages as tools for remodeling the microbiome is to engineer them ex vivo to express anti-inflammatory molecules or biosensors for specific diseases, or for the targeted binding to bacterial cells. Advances in synthetic biology have boosted the versatility and remarkable specificity of phages [31,32], and it is likely that these developments will serve as the basis for translation to clinical applications [33].

Phages can be used to effectively modulate the gut microbiota and metabolome in mouse models. For instance, in experiments using gnotobiotic mice colonized with defined human gut commensals and lytic phages, phage predation was found to directly impact susceptible commensals and led to additional effects on other bacterial species through interbacterial interations. Additional metabolomic profiling studies revealed that phage predation caused microbiome shifts, directly affecting the gut metabolome. Several studies, notably one by Hsu et al., have shown that phages can modulate bacterial colonization and could be used therapeutically to precisely modulate the microbiome community (Figure 2b) [34]. In another study, Hsu et al. orally administered an engineered temperate phage λ expressing a programmable dead Cas9 (dCas9) to repress the desired E. coli gene in the gut. Phages were delivered orally as an aqueous formulation consisting of layer-by-layer assembly of polyethylenimine/pectin. The system contained a controlled release mechanism where the phages were encapsulated in alginate; once the basic pH of the intestine (pH 6.4–7.5) was reached, the alginate capsules break open, facilitating phage release. As a result, a single dose of orally delivered phages changed bacterial gene expression in the gut and was able to modify the gut microbiome community in situ [35].

Despite these promising results, several drawbacks have limited the application of phage-mediated therapies [36]. Besides regulatory issues that complicate the application of tailor-made therapies [5], the obstacle most relevant to applying phage to the study of the microbiome is achieving stable engraftment [37–39], into the endogenous microbiota, of the engineered microbes targeted by the phages. To minimize the need for frequent dosing, long-term colonization is preferred for engineered microbes that secrete therapies over time. Current understanding of the colonization dynamics of particular bacterial species is limited, though colonization is known to depend on a variety of factors, including metabolic substrates, co-factors, and antimicrobial peptide expression. There is substantial variability in engraftment efficiency among different engineered strains because of inherent variations in the microbiome. Thus, it is challenging to achieve long-term engraftment of exogenous bacteria within a given microbiome population. One strategy for overcoming this challenge is, rather than engineering bacteria and then delivering them to the gut, to directly alter the endogenous microbiota. This can be achieved by in situ delivery of transgenes into specific microbiota members. Editing species that have previously established long-term colonization in the gut can effectively remodel bacterial communities for long periods of time. This strategy could directly translate to a need for fewer doses of bacteriophages, while reducing the overall cost and complexity of the therapy [36].

Small molecules

Small molecules, such as antibiotics and other organic compounds, have been widely explored as microbiome-targeting therapeutics [40]. These molecules were first considered readily available for microbiome-targeted drug design because their specific mechanisms of action against pathogenic strains were already known. Some of these small molecules have reached the stage of clinical trials [40]; however, the vast majority have encountered hurdles. The main barrier for their effectiveness is the ability of microbiome members to metabolize small molecules [41]. In a comprehensive study of 76 human gut microbiome strains, Zimmermann et al. reported that gut bacteria can chemically modify, and consequently metabolize, 271 orally administered drugs. The microbiome-encoded enzymes were shown to affect intestinal and systemic drug metabolism in a mouse model. Moreover, interpersonal differences in the composition of microbiome communities, especially when the microbiome is imbalanced, cause responses to standard drugs to vary widely. Such observations point to an urgent need for alternatives to known molecules that are less vulnerable to the defense mechanisms of the microbiome members. Small molecules that do not withstand these defenses can be redesigned, which is a focus for current work.

Alternatively, as Chen et al. reported, certain cyclic D-l-α-peptides can modify bacterial growth. These peptides were capable of remodelling the gutmicrobiome in a mouse model from the Western diet state to the low-fat-diet state [42]. Cyclic D-l-α-peptides are known for their high stability when exposed to proteolytic enzymes; this stability facilitates oral administration and biodistribution. Daily oral administration of the cyclic peptides led to reduced systemic cholesterol levels and atherosclerotic plaques in mice, while treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics depleted the microbiome and suppressed the effects observed with the peptide treatment.

New antimicrobial peptides with selective activity have also been designed for modifying the oral microbiome (Figure 2c). For example, an antimicrobial peptide moiety has been conjugated with a targeting domain, providing specificity towards a select organism. Specifically, the antimicrobial peptide novispirin G10 was conjugated to the targeting domain CSP derived from a Streptococcus mutans pheromone, resulting in the peptide C16G2. This molecule was able to selectively knock out S. mutans from a complex oral microbiome ecosystem, preventing dental caries pathogenesis while leaving other oral species unharmed. C16G2, which did not present cytotoxicity and completed Phase II trials for dental caries, is an alternative to broad-spectrum antibiotics and mouthwashes; following its administration, the intact oral community prevents reinfection by the pathogen [43]. These results support the use of molecular tools for sculpting other microbial communities, such as the gut microbiome. In fact, the same peptides might be valuable scaffolds for other potential microbiome-targeted therapeutics.

Conclusion and future perspectives

How microbes behave in complex communities and how their interactions change the effectiveness of targeted molecular tools are still fairly unknown. Computational-experimental frameworks used in drug discovery will be fundamental for identifying and rapidly testing potential molecular tools for probing the microbiome. As small molecules are not yet as precise as other genetic tools, which in turn rely on effective vectors or delivery mechanisms, the validation of those frameworks will be the next key step for precise modulation of endogenous microbiome members in communities. The future of this field will necessarily be linked to the discovery of effective molecular tools that enable large-scale and easy application, and it will involve the use and development of accurate biological descriptors, as well as an in-depth understanding of biological systems and pathways that are directly related to the human microbiome.

Increased engineering efficiencies, improved detection sensitivity, and more generalizable methods for the selection of microbiome-probing tools will expand the range of biological questions that can be answered. Ultimately, these tools should make it possible to precisely modulate the human microbiome and also to address the agricultural, industrial, and environmental issues that affect it.

Acknowledgements

Cesar de la Fuente-Nunez holds a Presidential Professorship at the University of Pennsylvania, is a recipient of the Langer Prize by the AIChE Foundation and acknowledges funding from the IADR Innovation in Oral Care Award, the Procter & Gamble Company, United Therapeutics, a BBRF Young Investigator Grant, the Nemirovsky Prize, Penn Health-Tech Accelerator Award, the Dean’s Innovation Fund from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number R35GM138201, and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA; HDTRA11810041 and HDTRA1-21-1-0014). We thank Dr. Karen Pepper for editing the manuscript. All figures were prepared in BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Cesar de la Fuente-Nunez provides consulting services to Invaio Sciences and is a member of the Scientific Advisory Boards of Nowture S.L. and Phare Bio. The de la Fuente Lab has received research funding or in-kind donations from Peptilogics, United Therapeutics, Strata Manufacturing PJSC, and Procter & Gamble, none of which were used in support of this work.

References

Papers of particular interest, published within the period of review, have been highlighted as:

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Surana NK, Kasper DL: Moving beyond microbiome-wide associations to causal microbe identification. Nature 2017, 552: 244–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fischbach MA: Microbiome: focus on causation and mechanism. Cell 2018, 174:785–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Fuente-Nunez C, Meneguetti BT, Franco OL, Lu TK: Neuromicrobiology: how microbes influence the brain. ACS Chem Neurosci 2018, 9:141–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeGruttola AK, Low D, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E: Current understanding of dysbiosis in disease in human and animal models. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2016, 22:1137–1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauconnier A: Phage therapy regulation: from night to dawn. Viruses 2019, 11:352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blicharz L, Rudnicka L, Czuwara J, Waskiel-Burnat A, Goldust M, Olszewska M, Samochocki Z: The influence of microbiome dysbiosis and bacterial biofilms on epidermal barrier function in atopic dermatitis—an update. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22: 8403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park DH, Kim JW, Park H-J, Hahm D-H: Comparative analysis of the microbiome across the gut–skin Axis in atopic dermatitis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22:4228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polak K, Bergler-Czop B, Szczepanek M, Wojciechowska K, Fratczak A, Kiss N: Psoriasis and gut microbiome—current state of art. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22:4529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Li J, Zhu W, Kuang Y, Liu T, Zhang W, Chen X, Peng C: Skin and gut microbiome in psoriasis: gaining insight into the pathophysiology of it and finding novel therapeutic strategies. Front Microbiol 2020:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin L, Shi X, Yang J, Zhao Y, Xue L, Xu L, Cai J: Gut microbes in cardiovascular diseases and their potential therapeutic applications. Protein Cell 2021, 12:346–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zamani S, Taslimi R, Sarabi A, Jasemi S, Sechi LA, Feizabadi MM: Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis: a possible etiological candidate for bacterially-induced colorectal precancerous and cancerous lesions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 9:449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu Y, Wang N, Tan H-Y, Li S, Zhang C, Feng Y: Function of Akkermansia muciniphila in obesity: interactions with lipid metabolism, immune response and gut systems. Front Microbiol 2020, 11:219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gu Z-Y, Pei W-L, Zhang Y, Zhu J, Li L, Zhang Z: Akkermansia muciniphila in inflammatory bowel disease and colorectal cancer. Chin Med J 2021, 134:2841–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolter M, Grant ET, Boudaud M, Steimle A, Pereira GV, Martens EC, Desai MS: Leveraging diet to engineer the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021, 18:885–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inda ME, Broset E, Lu TK, de la Fuente-Nunez C: Emerging frontiers in microbiome engineering. Trends Immunol 2019, 40:952–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Forslund SK, Chakaroun R, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Markó L, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Nielsen T, Moitinho-Silva L, Schmidt TSB, Falony G, Vieira-Silva S, et al. : Combinatorial, additive and dose-dependent drug–microbiome associations. Nature 2021, 600:500–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Durmusoglu D, Catella CM, Purnell EF, Menegatti S, Crook NC: Design and in situ biosynthesis of precision therapies against gastrointestinal pathogens. Curr Opin Physiol 2021, 23, 100453. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stewart Campbell A, Needham BD, Meyer CR, Tan J, Conrad M, Preston GM, Bolognani F, Rao SG, Heussler H, Griffith R, et al. : Safety and target engagement of an oral small-molecule sequestrant in adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: an open-label phase 1b/2a trial. Nat Med 2022, 28:528–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Needham BD, Funabashi M, Adame MD, Wang Z, Boktor JC, Haney J, Wu W-L, Rabut C, Ladinsky MS, Hwang S-J, et al. : A gut-derived metabolite alters brain activity and anxiety behaviour in mice. Nature 2022, 602:647–653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eberl C, Weiss AS, Jochum LM, Durai Raj AC, Ring D, Hussain S, Herp S, Meng C, Kleigrewe K, Gigl M, et al. : E. coli enhance colonization resistance against Salmonella Typhimurium by competing for galactitol, a context-dependent limiting carbon source. Cell Host Microbe 2021, 29:1680–1692. e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugimoto Y, Camacho FR, Wang S, Chankhamjon P, Odabas A, Biswas A, Jeffrey PD, Donia MS: A metagenomic strategy for harnessing the chemical repertoire of the human microbiome. Science (80-.) 2019, 366, eaax9176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sberro H, Fremin BJ, Zlitni S, Edfors F, Greenfield N, Snyder MP, Pavlopoulos GA, Kyrpides NC, Bhatt AS: Large-scale Analyses of human microbiomes reveal thousands of small, novel genes. Cell 2019, 178:1245–1259.e14. **Large-scale platform to identify microproteins and peptides derived from the human microbiome.

- 23. Torres MDT, Melo MCR, Crescenzi O, Notomista E, de la Fuente-Nunez C: Mining for encrypted peptide antibiotics in the human proteome. Nat Biomed Eng 2022, 6:67–75. *An algorithmic approach was used to mine the human proteome as a source of encrypted peptides that demonstrated anti-infective efficacy in mouse models.

- 24.Maier L, Pruteanu M, Kuhn M, Zeller G, Telzerow A, Anderson EE, Brochado AR, Fernandez KC, Dose H, Mori H, et al. : Extensive impact of non-antibiotic drugs on human gut bacteria. Nature 2018, 555:623–628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maier L, Goemans CV, Wirbel J, Kuhn M, Eberl C, Pruteanu M, Müller P, Garcia-Santamarina S, Cacace E, Zhang B, et al. : Unravelling the collateral damage of antibiotics on gut bacteria. Nature 2021, 599:120–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramachandran G, Bikard D: Editing the microbiome the CRISPR way. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 2019, 374, 20180103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin BE, Diamond S, Cress BF, Crits-Christoph A, Lou YC, Borges AL, Shivram H, He C, Xu M, Zhou Z, et al. : Species-and site-specific genome editing in complex bacterial communities. Nat Microbiol 2021, 10.1038/s41564-021-01014-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neil K, Allard N, Roy P, Grenier F, Menendez A, Burrus V, Rodrigue S: High-efficiency delivery of CRISPR-Cas9 by engineered probiotics enables precise microbiome editing. Mol Syst Biol 2021:17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ronda C, Chen SP, Cabral V, Yaung SJ, Wang HH: Meta-genomic engineering of the mammalian gut microbiome in situ. Nat Methods 2019, 16:167–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitfill T, Oh J: Recoding the metagenome: microbiome engineering in situ. Curr Opin Microbiol 2019, 50:28–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lenneman BR, Fernbach J, Loessner MJ, Lu TK, Kilcher S: Enhancing phage therapy through synthetic biology and genome engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol 2021, 68:151–159. *Recent review on the advances in phage-therapy and how phages have been used as tools for microbiome bacteria genome engineering.

- 32.Yehl K, Lemire S, Yang AC, Ando H, Mimee M, Torres MDT, de la Fuente-Nunez C, Lu TK: Engineering phage host-range and suppressing bacterial resistance through phage tail fiber mutagenesis. Cell 2019, 179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hsu BB: Towards the characterization and engineering of bacteriophages in the gut microbiome. mSystems 2021:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hsu BB, Gibson TE, Yeliseyev V, Liu Q, Lyon L, Bry L, Silver PA, Gerber GK: Dynamic modulation of the gut microbiota and metabolome by bacteriophages in a mouse model. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25:803–814. e5. **Engineered phages were able to repress target E. coli in the gut by enabling the expression of bacterial genes. Phages were orally administered as an aqueous-based formulation with a microbiota-based release mechanism, facilitating phage administration while minimizing disruption to host processes.

- 35.Hsu BB, Plant IN, Lyon L, Anastassacos FM, Way JC, Silver PA: In situ reprogramming of gut bacteria by oral delivery. Nat Commun 2020, 11:5030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voorhees PJ, Cruz-Teran C, Edelstein J, Lai SK: Challenges & opportunities for phage-based in situ microbiome engineering in the gut. J Contr Release 2020, 326:106–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lasaro M, Liu Z, Bishar R, Kelly K, Chattopadhyay S, Paul S, Sokurenko E, Zhu J, Goulian M: Escherichia coli isolate for studying colonization of the mouse intestine and its application to two-component signaling knockouts. J Bacteriol 2014, 196:1723–1732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Riglar DT, Giessen TW, Baym M, Kerns SJ, Niederhuber MJ, Bronson RT, Kotula JW, Gerber GK, Way JC, Silver PA: Engineered bacteria can function in the mammalian gut long-term as live diagnostics of inflammation. Nat Biotechnol 2017, 35: 653–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zmora N, Zilberman-Schapira G, Suez J, Mor U, Dori-Bachash M, Bashiardes S, Kotler E, Zur M, Regev-Lehavi D, Brik RB- Z, et al. : Personalized gut mucosal colonization resistance to empiric probiotics is associated with unique host and microbiome features. Cell 2018, 174:1388–1405. e21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cully M: Microbiome therapeutics go small molecule. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2019, 18:569–572. **Recent review on the use of known small molecules as molecular tools for probing the microbiome.

- 41.Zimmermann M, Zimmermann-Kogadeeva M, Wegmann R, Goodman AL: Mapping human microbiome drug metabolism by gut bacteria and their genes. Nature 2019, 570:462–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Chen PB, Black AS, Sobel AL, Zhao Y, Mukherjee P, Molparia B, Moore NE, Aleman Muench GR, Wu J, Chen W, et al. : Directed remodeling of the mouse gut microbiome inhibits the development of atherosclerosis. Nat Biotechnol 2020, 38: 1288–1297. *Cyclic stable peptides were able to inhibit the development of atherosclerosis in mice by directly remodeling the microbiome community.

- 43. Baker JL, He X, Shi W: Precision reengineering of the oral microbiome for caries management. Adv Dent Res 2019, 30:34–39. *Peptides with selective activity against S. mutans were used to prevent caries proliferation.