Abstract

We report a case of a patient with extensive-stage SCLC who developed acquired hemophilia A during maintenance atezolizumab therapy. The patient initially presented with asymptomatic anemia, a prolonged acquired prothrombin time, and factor VIII (FVIII) deficiency. Acquired FVIII autoantibodies were detected, confirming the diagnosis of acquired hemophilia. Atezolizumab was ceased and high-dose prednisolone was initiated. He subsequently developed an extensive spontaneous upper limb subcutaneous hematoma and shoulder hemarthrosis despite improving FVIII inhibitor titers on prednisolone. His acute bleeding was successfully treated with recombinant factor VII, and rituximab was added to prednisolone. Given the quiescent malignancy, 16 months of preceding treatment with atezolizumab, and improvement with immunosuppression, a diagnosis of immune checkpoint inhibitor–induced hemophilia A was made. Severe hematologic immune-related adverse events such as this case of acquired hemophilia have rarely been reported in the literature.

Keywords: Immunotherapy, Immune-related adverse events, Hemophilia, Factor VIII, Case report

Key Points

-

•

Acquired hemophilia A can be a rare complication of immune checkpoint inhibitors and should be suspected in cases of unexplained or disproportionate bleeding.

-

•

It is characterized by a raised activated partial thromboplastin time, which fails to correct in mixing studies and is confirmed by the detection of factor VIII inhibitor activity.

-

•

Inhibitor suppression is managed with corticosteroids plus or minus additional immunosuppressive agents.

-

•

There are limited data to guide decisions on immune checkpoint inhibitor cessation and rechallenge.

Introduction

Atezolizumab, an anti–programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, is an immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) approved for use in extensive-stage SCLC (ES-SCLC) in conjunction with platinum and etoposide chemotherapy. Whereas ICIs are generally well tolerated, patients may experience a range of immune-related adverse events (irAEs). Severe hematologic irAE are rare and remain poorly described.1

Acquired hemophilia A (AHA) develops as the result of acquired factor VIII (FVIII) autoantibodies.2 It generally presents with spontaneous and potentially life-threatening bleeding in adults with no history of bleeding disorders, and the cause may be cryptogenic in up to half of cases. In the remainder, it has been associated with concomitant autoimmune or inflammatory diseases, underlying malignancies, hepatitis, diabetes, and other causes. There have been four previous reports in the context of ICI (see Table 1).3, 4, 5

Table 1.

Summary of Reports of ICI Induced Hemophilia A and Their Management

| Author, Year | Characteristics | ICI and Time Since Initiation | Presentation | Coagulation Studies | Disease Status and Follow-Up | Treatment | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delyon 20113 |

44M Metastatic melanoma |

Ipilimumab 2 mo |

Macroscopic hematuria Hemorrhagic bladder metastases |

APTT 102 s FVIII < 1% FVIIIi 26 BU/mL |

NR Died 2 mo later |

Acute bleeding: rFVIIa 7 mg QID, activated prothrombin complex Inhibitor suppression: prednisone |

Treatment response. Bleeding controlled, but recurrent. |

| Kato 20185 |

68M Metastatic lung squamous cell carcinoma |

Nivolumab 17 mo |

Melena Gastric ulcer secondary to NSAID Hemorrhagic shock |

APTT 71s FVIII 3% FVIIIi 15 BU/mL |

Continued disease response | Acute bleeding: rFVIIa Inhibitor suppression: prednisone 1 mg/kg, cyclophosphamide 15 mg/kg |

Hemorrhage despite initial FVIII response to prednisone. Controlled with rFVIIa and immunosuppression. |

| Gozokan 20194 |

76M Metastatic lung squamous cell carcinoma |

Nivolumab 6 wk |

Extensive bruising and hematuria | APTT 93s FVIII <1% FVIIIi 31 BU/mL |

Disease response maintained further 10 mo until censor | Acute bleeding: rpFVIII 100 U/kg, then activated prothrombin concentrate (1000 U/kg daily) until FVIIIi resolved Inhibitor suppression: steroids, four doses of weekly rituximab 375 mg/m2 |

Clinical response, however persistent FVIIIi and prolonged APTT persisted for two weeks after discharge. Resolution of bruising, undetectable FVIIIi, and normal FVIII after 4 mo. |

| Kramer 20215 |

71M NR |

Pembrolizumab 128 wk |

NR | NR | NR | Acute bleeding: rFVIIa, FEIBA Inhibitor suppression: corticosteroids, rituximab |

Resolved after 29 d. Pembrolizumab was continued. Further details not reported. |

| Present case | 57M Metastatic lung squamous cell carcinoma |

Atezolizumab 16 mo |

Asymptomatic anemia Extensive bruising and hemarthrosis |

APTT 78 s FVIII 4% FVIIIi 14.6 BU/mL |

Continued disease response for further 3 mo until censor | Acute bleeding: rFVIIa 42 mg Inhibitor suppression: prednisolone 100 mg, four doses of weekly rituximab 100 mg |

Progressive haematoma and haemarthrosis despite initial factor response. Clinical improvement after rFVIIa. Weaned to prednisone 10 mg. No further bleeding events. Not rechallenged. |

APTT, activated prothrombin time; BU, Bethesda Units; FEIBA, factor eight bypassing agent; FVIII, factor VIII; FVIIIi, factor VIII inhibitor; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NR, not reported; NSAID, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug; QID, four times daily; rpFVIII, recombinant porcine factor VIII; rVIIa, recombinant activated factor VII.

Case Presentation

A 56-year-old man was diagnosed with ES-SCLC with a 40 mm by 63 mm primary tumor in the left upper lobe and extensive-stage disease involving mediastinal lymph nodes, sternum, and the left pectoral muscle (stage T3N1M1b). His medical history included hypertension, obesity, peripheral vascular disease, and cirrhosis with portal hypertension secondary to a history of eradicated hepatitis C, alcohol, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. He was an active smoker with a 40-pack-year history. There was no personal or family history of hematologic disorders.

The patient completed four cycles of palliative systemic therapy with carboplatin, etoposide, and atezolizumab, and achieved a substantial partial response on follow-up computed tomography (CT) scan.

After 16 months of therapy with atezolizumab and continued disease control, the patient presented with asymptomatic normocytic anemia (hemoglobin [Hb] = 67 g/liter, reference range: 135–180 g/liter). He was referred for outpatient hematologic investigation and a blood transfusion.

After 1 week, investigations revealed recurrent anemia (Hb = 67 g/liter) and evidence of an acquired FVIII inhibitor (FVIIIi). Clinical examination revealed no evidence of bleeding, bruising, decompensated liver disease, or cancer progression. The platelet count, thrombin time, and fibrinogen studies were normal. There was no evidence of decompensated liver function, hemolysis, or rise in urea levels. Activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT) was elevated (68 s, reference range: 25–38 s), which was only partially corrected with mixing studies (40 s, reference range: 25–38 s). FVIII activity was reduced (3%, reference range: 50%–150%), and acquired FVIIIi activity was detected (14.6 Bethesda units per milliliter [BU/mL]), establishing a diagnosis of AHA. CT revealed stable disease and no hemorrhage.

The differential diagnosis of the cause of acquired hemophilia was: (1) irAE, (2) paraneoplastic phenomenon, (3) cirrhosis, or (4) cryptogenic. There were no clinical or laboratory findings to suggest concurrent hematologic, immunologic, or infectious diagnoses, nor contributing medications that have previously been associated with AHA. Paraneoplastic acquired hemophilia, although possible, was considered less likely in view of greater than 12 months of disease control and continued disease response on restaging imaging. An irAE was considered most likely because of ongoing ICI before presentation.

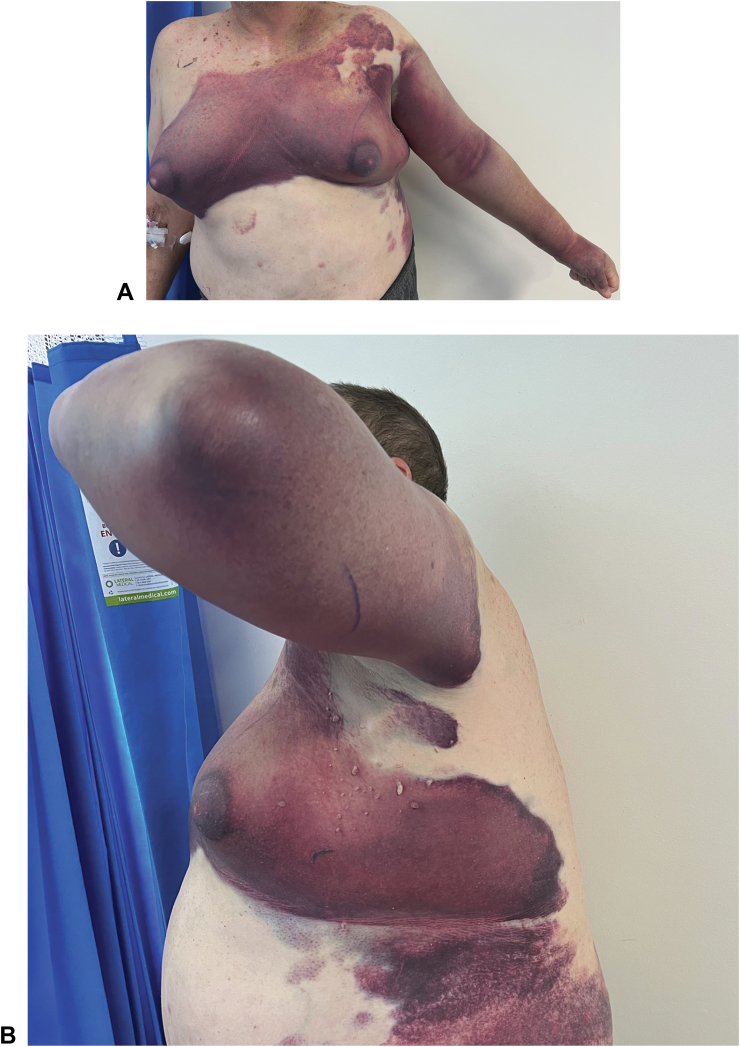

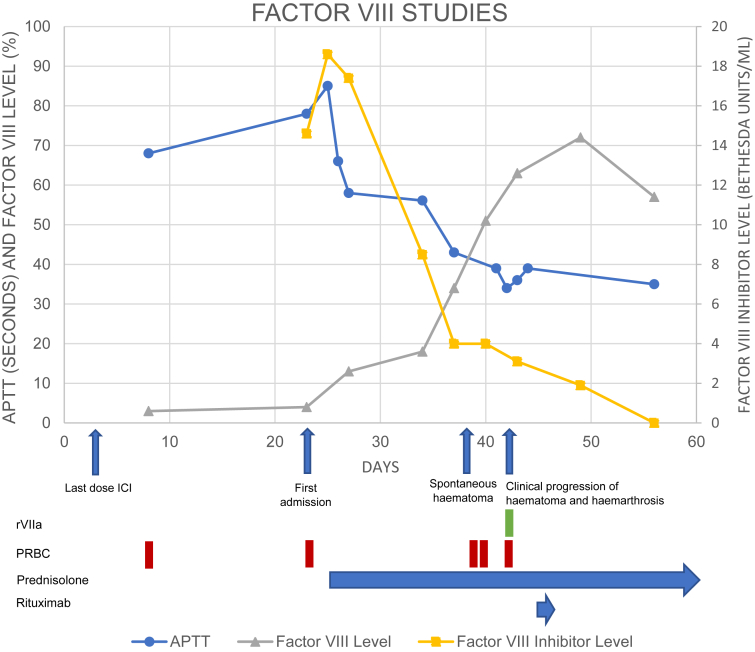

The initial management was blood transfusion, followed by correction of factor deficiency and suppression of factor inhibition. Atezolizumab was discontinued. The patient represented to the hospital after 1 week with a spontaneous and progressive left upper limb and chest wall hematoma (Fig. 1), despite initially responding to prednisolone 100 mg (FVIII 13%, APTT 58) (Fig. 2). He was managed with transfusion support and continued prednisolone with ongoing factor response and falling inhibitor titers (FVIII = 51%, FVIIIi = 4 BU/mL, APTT = 36). However, the hematoma clinically progressed, and imaging revealed a new left shoulder hemarthrosis. Impaired factor function was addressed with three doses (42 mg total) of activated recombinant factor VII (rFVIIa) over 6 hours, and rituximab 100 mg weekly was commenced. There were no further bleeding sequelae and the patient was discharged home.

Figure 1.

Clinical photographs taken on day five of admission from (A) anterior, and (B) lateral aspects. The patient had been treated with prednisolone 100 mg and was clinically responding to therapy. Incidental note is made of gynecomastia as a stigmata of chronic liver disease.

Figure 2.

A timeline of key clinical developments, laboratory findings, and interventions. Presented as days after initial presentation with asymptomatic anemia. APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; rVIIa, activated recombinant factor VII; PRBC, packed red blood cell.

Over the next 4 weeks, prednisolone was weaned to 15 mg and four total doses of rituximab were administered. Factor levels recovered to the reference range (57%) and the inhibitor was suppressed (1.4 BU/mL). After 3 months of the initial presentation, there had been no further bleeding sequelae, and positron emission tomography with CT confirmed a complete metabolic response.

Discussion

Here, we present an interesting case of AHA manifesting with spontaneous subcutaneous hemorrhage and hemarthrosis in the context of ICI for SCLC. Acute bleeding complications were managed with rFVIIa, and inhibitor suppression with prednisolone and rituximab was successful.

There have been four previous reports of ICI-induced AHA (Table 1).1,3, 4, 5 The onset ranged from 6 to 128 weeks after initiating ICI, in keeping with delayed-onset severe irAE.1 In each case, acute bleeding complications were addressed with hemostatic factor support, and immunosuppression was initiated. Similar to our case, escalation of immunosuppression to include cyclophosphamide,4 or more recently rituximab,5 was clinically effective and in keeping with published guidelines.2 Despite clinical improvements, prolonged APTT, and elevated FVIIIi persisted for some months in our case, and in two previous cases.4,5 A case of pembrolizumab-associated AHA was successfully managed with corticosteroids, rituximab, rFVIIa, and FVIII bypassing agent.1 Pembrolizumab was continued in this case; however, further clinical and laboratory details were not available. There are no other further reports of outcomes regarding rechallenging ICI in the context of ICI-induced AHA.

A strength of this report was the consideration of a paraneoplastic cause, as AHA has been reported in association with ES-SCLC.6,7 One recent case documented successful eradication of FVIIIis with corticosteroids before initiation of chemotherapy and atezolizumab, which resulted in more than 12 months of disease control without recurrence of the FVIIIi.7 Two of the previous case reports have addressed this differential diagnosis and, similar to our present case, thought this was unlikely owing to disease response on imaging.4,5 The duration of continued ICI also lends weight to this conclusion.4 However, differentiating the cause can be fraught with uncertainty. In a separate case of AHA presenting as melena in the context of ES-SCLC with stable disease on atezolizumab, authors considered the diagnosis of paraneoplastic AHA to be more likely as the prolonged APTT was refractory to corticosteroids and cessation of ICI.8 In contrast with the present case, the patient did not receive additional immunosuppressive therapy, and they were subsequently rechallenged with ICI.8 It is difficult to draw further comparisons as data regarding their bleeding history, APTT, FVIII activity, and FVIIIi activity over time were not reported, nor whether reintroduction of ICI at a later date affected these. Nevertheless, the increased incidence of AHA with SCLC as compared with other malignancies, and the shorter period of follow-up remains a limitation in our case. Paraneoplastic processes may predate cancer diagnoses and herald further disease progression, though this has not been reported with AHA.

Though rare, physicians using ICI should be aware of this diagnostic possibility in clinical scenarios of unexplained considerable bleeding. This case also highlights that we cannot be complacent with ICI use, as severe late irAEs (>12 mo) do occur.

Conclusions

Clinicians should be alert to the possibility of severe immune-related hematologic toxicity secondary to ICIs. The management of immune-mediated AHA was in keeping with published guidelines, and to date, all reported cases have revealed improvement with factor support and immunosuppression. Further data are required to determine longer-term outcomes of this rare complication.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement

James Fletcher: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Project administration.

Robert Bird: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Supervision.

Andrew JW McLean: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – review and editing.

Kenneth O’Byrne: Writing – review and editing, Supervision, Funding acquisition.

Wen Xu: Conceptualization, Writing – review and editing, Supervision.

Acknowledgments

This case report was supported by the Division of Cancer Services, Princess Alexandra Hospital. No funding was received for this case report. The authors confirm that written informed consent was provided for this case report and included clinical images.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Cite this article as: Fletcher J, Bird R, McLean AJW, O’Byrne K, Xu W. Acquired hemophilia A secondary to an immune checkpoint inhibitor: case report. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2022;3;100409.

References

- 1.Kramer R., Zaremba A., Moreira A., et al. Hematological immune related adverse events after treatment with immune checkpoint inhibitors. Eur J Cancer. 2021;147:170–181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2021.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tiede A., Collins P., Knoebl P., et al. International recommendations on the diagnosis and treatment of acquired hemophilia A. Haematologica. 2020;105:1791–1801. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2019.230771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delyon J., Mateus C., Lambert T. Hemophilia A induced by ipilimumab. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1747–1748. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1110923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gokozan H.N., Friedman J.D., Schmaier A.H., Downes K.A., Farah L.A., Reeves H.M. Acquired hemophilia A after nivolumab therapy in a patient with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the lung successfully managed with rituximab. Clin Lung Cancer. 2019;20 doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2019.06.022. e560–e563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato R., Hayashi H., Sano K., et al. Nivolumab-induced hemophilia A presenting as gastric ulcer bleeding in a patient with NSCLC. J Thorac Oncol. 2018;13:e239–e241. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shwaiki A., Lara L., Ahmed F., Crock R., Rutecki G.W., Whittier F.C. Acquired inhibitor to factor VIII in small cell lung cancer: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Hematol. 2001;80:124–126. doi: 10.1007/s002770000246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pauls M., Rydz N., Nixon N.A., Ezeife D. Paraneoplastic acquired haemophilia A in extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC) in the era of immunotherapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-236973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon J.F., Basnet A. Acquired hemophilia as a paraneoplastic syndrome in a patient with small cell lung carcinoma. Cureus. 2022;14 doi: 10.7759/cureus.23926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]