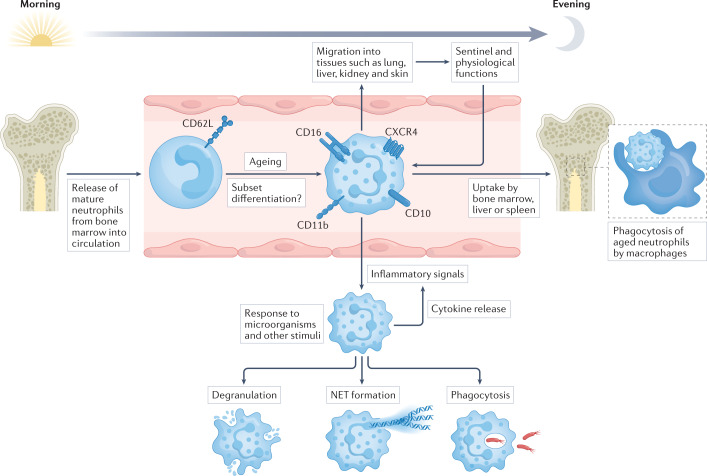

Fig. 1. The life cycle and functions of neutrophils.

Mature neutrophils are released from the bone marrow into the circulation. Circadian rhythm regulates the biology of neutrophils, their release from the bone marrow and their migration into tissues, but these processes are also modified by inflammatory conditions that involve an increased systemic demand for neutrophils. Most neutrophils have a short half-life and live for only 1 day or less in the circulation. During this time, the expression of several surface markers increases as neutrophils age, including CD16 (also known as FcγRIII), CD10, CD11b (also known as integrin αM) and the chemokine receptor CXCR4. This allows for the entry of neutrophils into other tissues, such as lung, liver, kidney and skin, where they carry out sentinel functions surveying for invading microorganisms as well as physiological functions, including angiogenesis, coagulation and tissue repair. It is still unclear if these tissue-resident neutrophils represent functional subsets, or if neutrophil subsets, such as low-density granulocytes, can be detected in the circulation. The end of the neutrophil life-cycle involves the bone marrow, liver or spleen, where neutrophils can be phagocytosed and degraded by macrophages. If neutrophils encounter an inflammatory signal, they can exit the circulation by extravasation to reach the site of injury. Neutrophils can respond to microorganisms in several ways, including intracellular degradation (phagocytosis), extracellular degradation (degranulation), and extracellular trapping and degradation (neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation).