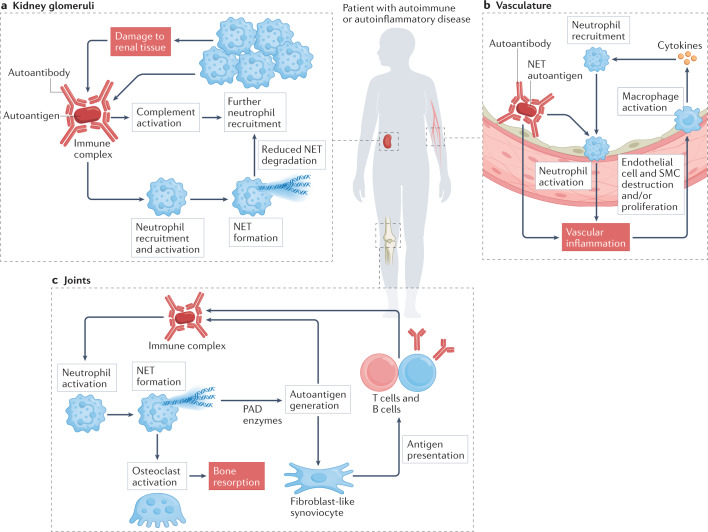

Fig. 3. Organ-specific effects of neutrophils in autoimmune and autoinflammatory diseases.

a | In some autoimmune conditions, such as systemic lupus erythematosus and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, glomerulonephritis occurs associated with the deposition of circulating immune complexes in the kidney glomeruli that can promote neutrophil recruitment and aggregation. The resulting complement activation and neutrophil extracellular trap (NET) formation recruit further immune cells and damage renal tissue, which leads to the exposure of additional autoantigens and formation of more immune complexes. b | The vasculature can be affected in most autoimmune conditions in some form, including rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Circulating immune complexes that contain NET autoantigens coupled with autoantibodies may contribute to vascular inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. NET products can have a direct pathogenic effect on the vessel wall by destroying endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells (SMCs). Activated neutrophils can infiltrate the endothelium, triggering monocytes and macrophages to release cytokines that recruit more immune cells. c | The joints are also a common target in autoimmunity. Neutrophils can attack joint structures promoting pain, inflammation and loss of function. Several molecules released from neutrophils cause modification and subsequent destruction of cartilage and bone, triggering an adaptive immune response against self-targets and promoting the development of autoantibodies. These autoantibodies can form immune complexes in the joint, further activating neutrophils and leading to NET formation. PAD, peptidylarginine deiminase.