Abstract

In this study, cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) (cPNIPAAM) was synthesized in supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) using emulsion and homogeneous reactions for the first time. This was accomplished by applying free radical polymerization and nitroxide compounds to produce low molecular weight precursors in the SC-CO2 solvent. The cyclization reaction occurred in a homogeneous phase in the SC-CO2 solvent, with dimethylformamide (DMF) serving as a co-solvent for dissolving the linear precursor. This reaction was also conducted in emulsion of SC-CO2 in water. The effects of pressure and time on the morphology, molecular weight, and yield of a difunctionalized chain were investigated, where a higher pressure led to a higher yield. The maximum yield was 64% at 23 MPa, and the chain molecular weight (Mw) was 4368 (gr/mol). Additionally, a lower pressure reduced the solubility of materials (particularly terminator) in SC-CO2 and resulted in a chain with a higher molecular weight 9326 (gr/mol), leading to a lower conversion. Furthermore, the effect of cyclization reaction types on the properties of cyclic polymers was investigated. In cyclic reactions, the addition of DMF as a co-solvent resulted in the formation of a polymer with a high viscosity average molecular weight (Mv) and a high degree of cyclization (100%), whereas the CO2/water emulsion resulted in the formation of a polymer with a lower Mv and increased porosity. Polymers were characterized by 1HNMR, FTIR, DSC, TLC, GPC, and viscometry tests. The results were presented and thoroughly discussed.

Subject terms: Chemical engineering, Chemical engineering

Introduction

Synthetic polymers are intriguing drug delivery candidates. Polymers usually show longer circulation time and the potential for tissue targeting1. The physical and chemical properties of the polymeric carriers are critical to the therapy’s success. Amongst these attributes, the shape of the carrier has been identified as one of the key factors2,3.

Cyclic polymers may be an innovative choice for this purpose due to their unique properties and cyclic structure. They take the form of rings or macrocycles, and due to the absence of chain ends, all repeating units are physically and chemically equivalent. In fact, the cyclic form excludes any possible reactions with terminal groups; thus, their properties are unaffected by such groups. They exhibit increased blood circulation times, increased permeability, and an effect on tumor tissue retention. In comparison to the linear type, they exhibit lower viscosity, higher glass transition temperature, higher critical solution temperature, smaller hydrodynamic volume and radius of gyration, higher rate of crystallization, higher refractive index, lower translational friction coefficient, and a more rapid decrease in the second virial coefficient with molecular weight4–15. Additionally, the delayed mass loss of biodegradable cyclic polymers prolongs their circulation in the bloodstream4,16.

Among cyclic polymers, cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) (cPNIPAAM) is a water-soluble polymer with a distinct thermal phase transition behavior, making it an intriguing candidate for use as a suitable carrier in drug delivery. This polymer has been synthesized by applying different methods. These include the atom transfer radical polymerization (ATRP) of functionalized chains followed by click cyclization9,15. Another method combines a click reaction based on anthracene and thiol with reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer polymerization (RAFT). Moreover, it is formed by the ring closure of a heterodifunctional telechelic PNIPAAM precursor15,17.

Due to the absence of organic solvents and thus consideration of human and environmental protection, the use of supercritical carbon dioxide (SC-CO2) as a solvent in polymerization is an attractive alternative, particularly when producing medicine carrier polymers. This medium has been used commercially for an extended period in the pharmaceutical, textile, and food industries18–20. Because it is inexpensive, non-toxic, non-flammable, relatively inert, odorless, and requires no energy to remove, it is promoted as a green solvent. Furthermore, its properties are tunable via pressure and temperature adjustments20,21. Furthermore, it has many applications in various fields such as essential and seed oils extraction22–27, solubility28–58, nanoparticle formation44,59–65, impregnation66,67 and etc.

SC-CO2 is also a suitable solvent for nonpolar molecules with low molecular weight and small polar molecules. Moreover, water and ionic compounds are insoluble in SC-CO2. The mass transfer coefficients of components are greater in SC-CO2 than in other media. As a result of this property, the reaction rates in SC-CO2 improve68. Low viscosity, high mass transfer, and diffusivity contribute to reducing the probability of the Trommsdorf effect during polymerization. Other advantages of SC-CO2 include obtaining dry polymers after depressurizing the reactor and modifying the crystallinity of products.

Furthermore, polymers’ glass transition temperature (Tg) is reduced in this solvent69–71 Therefore, SC-CO2 offers an excellent opportunity to process new advanced materials21,72. However, due to synthetic challenges, the applications of cyclic polymers remain unexplored4. As a result, the polymerization of functionalized precursors and the cyclic reactions that occur in SC-CO2 is also obscure. Following a review of the literature, it was observed that Mase et al. produced cPLA in the SC-CO2 for the first time in 201873. Daneshyan and Sodeifian recently produced cyclic polystyrene in SC-CO2 and considered the different condition of reaction74.

According to the benefits of SC-CO2 media and since the synthesis of cPNIPAAM in SC-CO2 has not yet been reported; thus, in this research, cPNIPAAM was synthesized using the Deffieux method by applying unimolecular cyclization of linear -heterodifunctional PNIPAAM as third polymer synthesized in SC-CO215. To this end, radical polymerization via nitroxide compounds (4-hydroxy-TEMPO as the terminator) was utilized to create a difuntionalized chain of PNIPAAM in SC-CO2 solvent in the presence of 4, 4’ azobis (4-cyanovaleric acid) as the initiator. In this process, precipitation polymerization of NIPAAM was carried in SC-CO2. The initiator, terminator, and monomer are soluble in the SC-CO2 depending on the solvent's pressure and density75–77. The radicals are inert in the CO2, so there is no chain transfer to this solvent76. Difunctionalized chains started to precipitate when their molecular weight became higher than the critical molecular weight75,78. Functionalized polymer chains separated and gathered in the bottom of the reactor in the form of puffy ivory powder.

The cyclization reaction was performed in SC-CO2 using end-to-end equilibrium and the coupling agent 2-Chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide. The reaction took place in two distinct reaction procedures. Dimethylformamide (DMF) was used as a co-solvent in the first process. In this condition, the coupling agent, activator and solution of polymer and co-solvent made a homogenous phase, according to the equilibrium phase of DMF and SC-CO2 and solubility of materials in SC-CO279,80. As the time of reaction became over, the produced solution of cPNIPAAM in the form of yellow liquid was obtained.

The second reaction was performed in a CO2/water emulsion. In this condition, the reaction occurred in continues matrix of water; because of SC-CO2 is immiscible in water, therefore it makes an emulsion of CO2/Water. At the end of reaction solution of cPNIPAAM in water formed a yellow liquid. The final products lyophilized to obtain a polymer in the form of powder.

The products were characterized through different analyses, including 1HNMR, IR, GPC, SEM, DSC, and viscometry. Moreover, the effect of pressure and time on the morphology and molecular weight of the polymer and the effect of emulsion and homogenous reactions on the polymer’s characterization and cyclization yield were investigated and reported.

Experimental section

Materials

N-isopropylacrylamide (Sigma Aldrich, 99%), Triethylamine (BDH, HPLC Grade, 99.5%), Dimethylforamide (DMF) (BDH, spectroscopy Grade, 99.5%), 4,4′-azobis(4-cyanovaleric acid), (Sigma Aldrich, ≥ 75%) as initiator, 4-hydroxy-TEMPO (Sigma Aldrich, 97%) as terminator, 2-chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide (Sigma Aldrich, 97%) as coupling agent for cyclization, Methanol (Merck, Chromatography Grade, 99.8%), deionized water and CO2 gas (99.99%, Fadak company of Iran) were purchased and applied for this research.

Supercritical carbon dioxide production and reaction apparatus

As shown in Fig. 1, the experimental setup is included a refrigerator (E-1) to liquefy the gaseous CO2, and a high-pressure pump (P-1) to supply the required pressure. The pressurized liquid carbon dioxide was converted to the supercritical fluid by passing through a heat exchanger (E-3).

Figure 1.

SC-CO2 producing and reaction apparatus. (E-1) Refrigerator, (E-2) water heater, (E-3) Heat exchanger, (E-4) Heater stirrer, (F-1) Filter, (P-1) High pressure pump, (P-2) Air compressor, (T-1) CO2 tank, (T-2) Polymerization reactor, (T-3) Paraffin bath, * (T-4) vent collector, (T-5) Water tank, (V-1) One-way pressure breaker valve, (V-2) Vent valve. *This is a glass open-door column.

The high-pressure pump (P-1) and heat exchanger (E-3) were controlled by a control panel which adjusted the output pressure of the pump and output temperature of the fluid leaving the heat exchanger. The pressure of the pump was controlled by making off and on the air compressor (P-2). The exit temperature of the heat exchanger was controlled by switching on and off the heater located in the water supplying tank (E-2).

The polymerization and cyclization reactions occurred in a 150 ml cylindrical, stainless vessel (T-2). Considering the disc material and system limitations, the maximum temperature and pressure that could be supplied by reactor were (90 ± 1 °C) and (25 MPa ± 0.1), respectively. A magnetic stirrer (E-4) with maximum rotation velocity 1500 rpm was employed to improve the mixing of materials. The reactor temperature was maintained using a paraffin bath (T-3).

CO2 entered the filter (F-1), then passed through the line of the refrigerator (E-1). Cold CO2 was then pressurized by the high-pressure pump (P-1). To reach the supercritical point, the heat exchanger (E-3) enhanced the temperature of CO2 utilizing warm water. Finally, the SC-CO2 entered to the reactor (T-2). Paraffin bath (T-3) kept the reaction temperature constant. The required heat and agitation of materials were supplied by a heater-stirrer (E-4). Using this reactor, polymerization and cyclization reactions could be performed by SC-CO2 at different pressures.

Methods

Producing linear difunctionalized precursor

The linear precursor was synthesized via controlled free-radical polymerization of NIPAAM with 4,4′azobis(4-cyanovaleric acid) as the initiator and 4-hydroxy-TEMPO as the terminator. The optimum Wi/Wm and Wt/Wi ratios were 1.5% and 83.3%, respectively. The exact amounts of materials are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The amount of raw materials used for producing difunchtionalized polymer chains.

| Component | Mol | Mass (gr) |

|---|---|---|

| NIPAAM | 0.0176 | 2 |

| Initiator | 0.000107 | 0.03 |

| Terminator | 0.000145 | 0.025 |

| SC-CO2 | 0.96 and 1.23a | 42.24 and 54.12 |

aThese quantities were used for two different pressures level.

The NIPAAM monomer, initiator, and terminator were added to the purged reactor to produce a linear precursor. SC-CO2 solvent was introduced into the reactor at various pressures following complete sealing. The stirring speed was 1500 rpm.

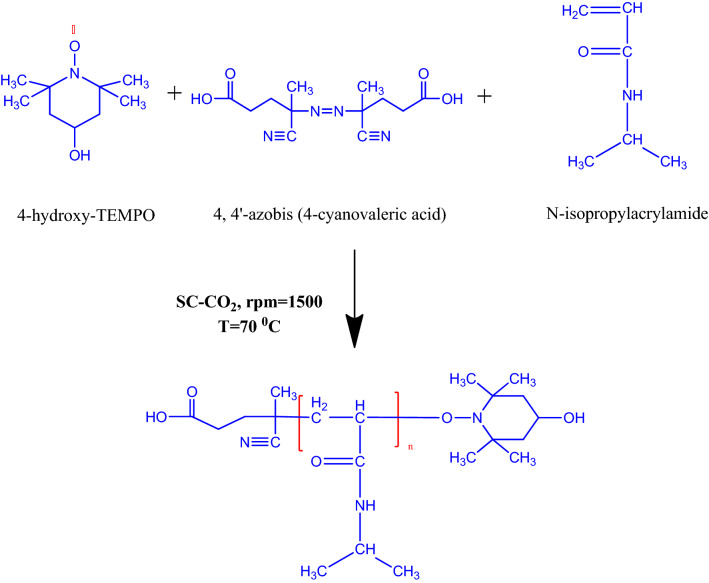

The initiator’s minimum activation temperature is 70 °C, in addition due to the thermosensitivity of the monomer and the previous researches, polymerization temperature was maintained at 70 °C76,77,81,82. According to previous researches, polymerization reaction below 10 MPa has no yield. Because the monomer is solid, it is insoluble in the SC-CO2 at these pressures76,77. Besides minimum pressure for dissolving terminator and initiator in SC-CO2 in temperature of 70 °C is 15 MPa74. Then by considering apparatus operation limitation, two pressure levels (20 and 23 MPa) were considered to study the effect of pressure. The reaction that occurred in the reactor is depicted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Synthesis of difunctionalized PNIPAAM in SC-CO2.

The polymerization is classified as a heterogeneous polymerization. The monomer, initiator, and terminator were dissolved in SC-CO2 solvent75–77. In fact, SC-CO2 was performing as a solvent in this process. Since the viscosity of SC-CO2 is low (near the gas), which has a density near the liquid, then stirring at a high rate (1500 rpm), leads to a high mass transfer coefficient, and the high diffusivity of materials with high effective collision in the continuous phase resulted in a nearly homogeneous phase21. Difunctionalized polymer precipitated at the bottom of the reactor when their molecular weight became higher than critical molecular weight75. At the end of the reaction when the reactor was cooled down to the ambient temperature, the reactor was depressurized and discharged in one minute (by rate of 2.5 ml/s) by releasing the reactor's exit valve. Unreacted raw materials dissolved in SC-CO2 and were collected in the open-door vent collector, as shown in Fig. 3. This polymer is not soluble in SC-CO2, thus all the product remained at the bottom of the reaction vessel and did not exit by discharged solvent79.

Figure 3.

Residual raw materials, exited from the reactor by SC-CO2 after depressurizing.

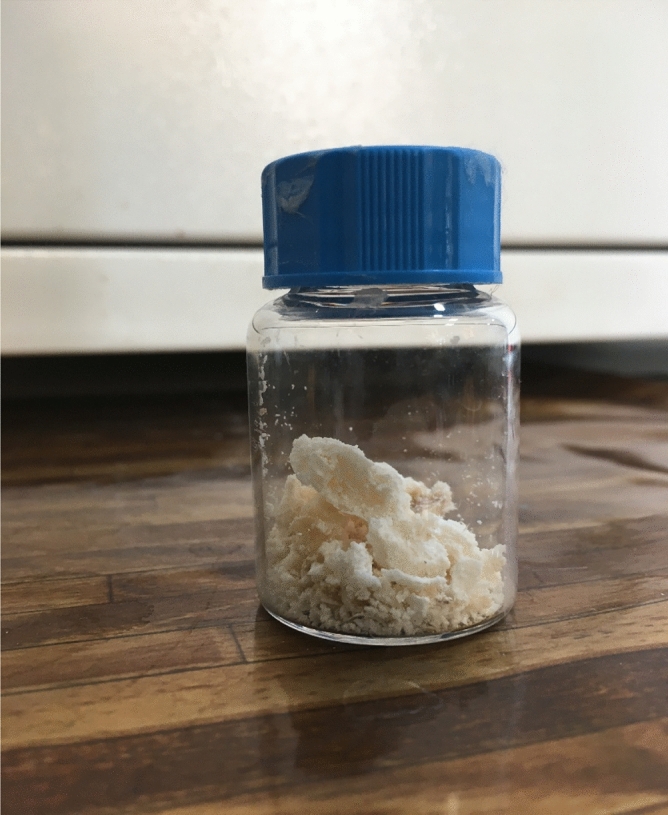

As illustrated in Fig. 4, the difunctionalized precursor appeared as puffy ivory powder. The product weight ratio to the monomer weight was determined as the polymerization yield. The formation of the precursor was confirmed by characterization analysis. The effect of time and pressure of SC-CO2 was examined and discussed in the following sections.

Figure 4.

Difunctionalized PNIPAAM produced in SC-CO2.

Cyclization reaction and producing cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)

Esterification or lactonization reactions were conducted by the end-to-end equilibrium method in this section, involving the reaction of alcoholic OH and carboxylic acid function and the separation of water molecules to produce a ketone or a large lactone ring15,83. As shown in Fig. 5, 2-Chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide with a Wpi/Wp = 1.5 and triethylamine with a Wtea/Wp = 1.2 was used as coupling agent and activator, respectively. The exact amounts of materials are shown in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 5.

Synthesis of cPNIPAAM in SC-CO2 by using lactonization reaction.

Table 2.

Amount of raw materials used in the synthesis of cPNIPAAM in SC-CO2 and co-solvent of DMF.

| Materials | Mol | Mass (gr) |

|---|---|---|

| Difunctionalized polymera | 0.000072 | 0.3 |

| Coupling agent | 0.00176 | 0.45 |

| Activator | 0.00356 | 0.36 |

| SC-CO2 | 0.86 | 37.84 |

| DMF | 0.0387 | 2.832 (3 ml) |

aDifunctionalized polymer was synthesized in condition of P = 23 MPa during 12 h, T = 70 , Wi/Wm = 1.5%, Wt/Wi = 83.3%, Mw = 4165 (gr/mol), Mn = 1488 (gr/mol) PDI = 2.8, and Mp = 1039 (gr/mol).

Table 3.

Amount of raw materials used for the synthesis of cPNIPAAM in emulsion of CO2/Water.

| Materials | Mol | Mass (gr) |

|---|---|---|

| Difunctionalized polymera | 0.000072 | 0.3 |

| Coupling agent | 0.00176 | 0.45 |

| Activator | 0.00356 | 0.36 |

| SC-CO2 | 1.15 | 50.6 |

| Methanolb | 0.0742 | 2.376 (1 ml) |

| H2O | 0.17 | 3 (3 ml) |

aDifunctionalized polymer was synthesized in condition of P = 23 MPa during 12 h, T = 70 , Wi/Wm = 1.5%, Wt/Wi = 83.3%, Mw = 4165 (gr/mol), Mn = 1488 (gr/mol) PDI = 2.8, and Mp = 1039 (gr/mol).

bMethanol was used as co-solvent in water solvent for dissolving coupling agent.

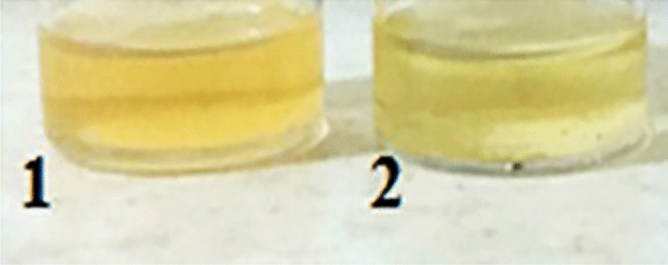

Homogeneous cyclization reaction

Due to the insoluble nature of the linear precursor in SC-CO2 solvent, a small amount of DMF was used as a co-solvent. The coupling agent and activator were added after the polymer was dissolved. The reactor was injected with SC-CO2 at a pressure of 15 MPa. This pressure, as shown in our recent research, provided the low molecular weight difunctionalized chains, completed cyclization yield74. Since the reaction was exothermic and reaction’s temperature was constant, then the pressure increased to 22 MPa. Thus, the average pressure which the reaction was performed in it was 18.5 MPa. The reaction was carried out for 16 h at a temperature of 45 °C. This condition was the same as the previous researches, for achieving high cyclization yield and thermosensitively of difuntionalized chains74,84. The stirring rate was set to 1500 rpm. Since DMF is partially soluble in SC-CO2, high-speed stirring, high diffusion, and a high mass transfer coefficient resulted in a nearly homogeneous phase according to the SC-CO2 and DMF phase equilibrium. cPNIPAAM and by-products were soluble in the co-solvent. After cool down and depressurizing SC-CO2 (during one minute (by rate of 2.5 ml/s)), some of by-products of the cyclization reaction and the co-solvent exited from the reactor; according to their solubility in the SC-CO2. The cyclic product remained at the bottom of the reaction cell in the form of a yellow liquid (see Fig. 6)21,79,80. The solution was lyophilized (freeze-drying). Figure 7 illustrates the final polymer in the form of ivory powder.

Figure 6.

1—cPNIPAAM solution in DMF; 2—cPNIPAAM solution in water before lyophilizing.

Figure 7.

cPNIPAAM produced in homogenous phase of SC-CO2 solvent and DMF co-solvent after lyophilizing.

Emulsion cyclization reaction

As water is immiscible in SC-CO2, then its droplets dispersed in the water and formed an emulsion of SC-CO2 in water. This is a green method to produce porous hydrophilic polymers21. Cyclization reaction was performed in an aqueous phase. Finally, a porous polymer was formed.

For this purpose, the difunctionalized polymer was first dissolved in water prior to this reaction. In a droplet of methanol, the coupling agent and activator were dissolved. Following that, these two solutions were homogenized and added to the reactor. SC-CO2 was introduced at a pressure of 20 MPa after sealing due to make low size droplets and stable emulsion, according to apparatus’ operation limitation85. Since the reaction occurred in the water phase was endothermic, then in the constant temperature, it led to decrease the pressure of system about 7 MPa. Thus the average pressure which the reaction was performed in it was 16.5 MPa. The reaction was carried out for 16 h at a temperature of 45 °C for achieving high cyclization yield and thermosensitively of difuntionalized chains, respectively74.

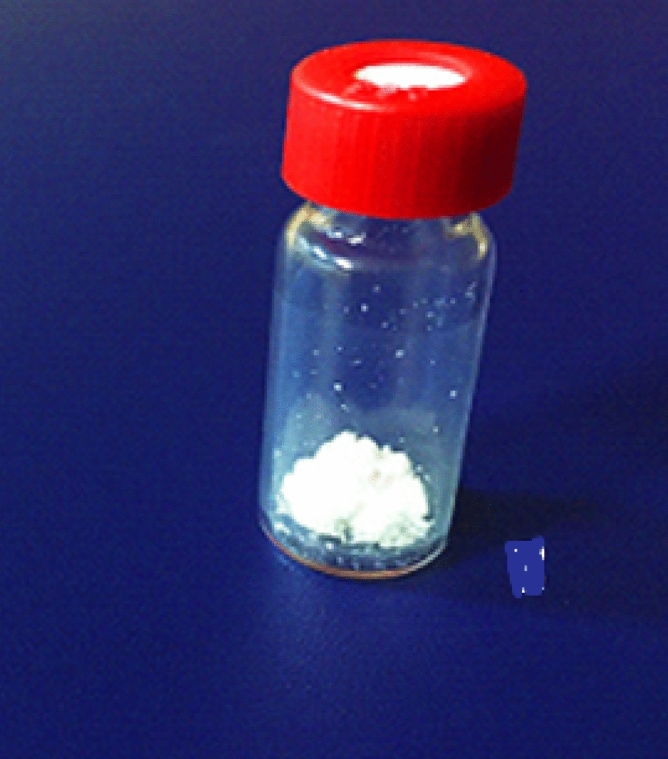

After cool down and depressurizing SC-CO2 (during one minute (by rate of 2.5 ml/s)), The yellow solution remained at the bottom of the reactor, as illustrated in Fig. 6. The solution was lyophilized, and the resulting polymer was a white powder, as depicted in Fig. 8. The products were identified, and the reaction type’s effect was evaluated and reported.

Figure 8.

cPNIPAAM produced in emulsion of SC-CO2 in water after lyophilizing.

Hydrogen nuclear magnetic resonance

This test identifies the position of hydrogen atoms in the compound85. The analysis was accomplished by Bruker NMR spectrometer of Germany, with frequency about 400 MHZ, using dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) solvent.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

Infrared spectra were recorded on FTIR Bruker-Alpha of Germany, which makes available the spectrums in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 using KBr tablet for a polymer powder.

Molecular weight distribution

Mw distribution was measured by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (Agilent -1100 series, USA) using tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent.

Measurement of the viscosity average molecular weight

The intrinsic viscosity of polymer solutions in water were measured at the concentration of 0.002 to 0.0033 (gr/ml) and ambient temperature, using Cannon–Fenske (Italy) viscometer 25 ml, with viscosity constant of 0.001477. The molecular weight of cPNIPAAM was determined, applying the Mark-Houwink equation () by assuming its constants a = 1.1, for cyclic polymer produced by emulsion reaction and a = 1.5, for homogeneous reaction in co-solvent of DMF. The value of k = 0.46 × 10–5 (dl/gr) as previously reported for PNIPAAM solution in water86,87.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Tg and melting point (Tm) of crystalline polymers were measured utilizing differential scanning calorimetry (DSC)88. DSC (Mettler TC-11 of Switzerland) was carried out in the temperature range of 27–250 °C at a heating rate of 10 (°C/min), under nitrogen atmosphere.

Scanning electron microscopy

The morphology of synthesized polymers is recognized by SEM. The scanning electron microscope Phenom (model Prox, Netherlands) was used. To obtain high quality images all of the samples were coated with a gold thin layer.

Thin layer chromatography

This experiment is applied for the identification and separation of different spices in the compounds on the basis of polarity. In this research, silica gel paper was used as a stationary phase, and the solution of ethyl acetate and n-hexane with the ratio of 1:4 has been considered as a mobile phase. Using this method, cyclization yield was qualitatively signified.

Results and discussion

Characterization of difunctionalized poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)

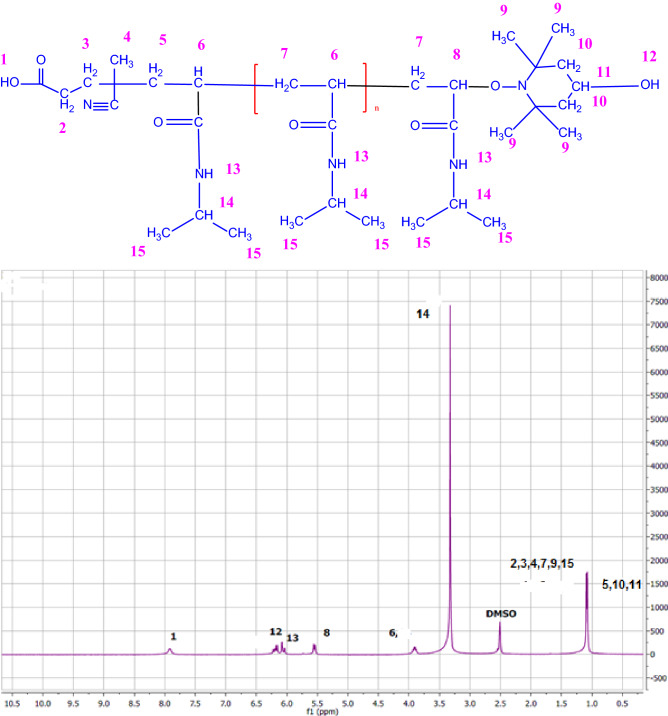

Hydrogen nuclear magnetic resonance analysis

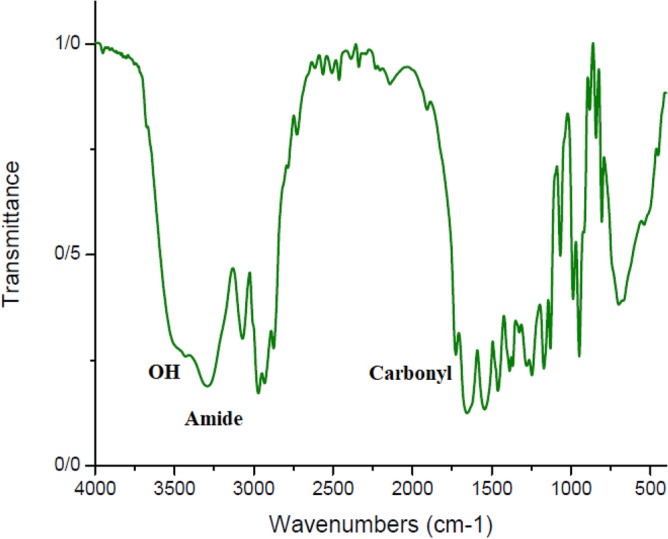

Displacement at 8 and 6 ppm beside the specified functional groups and chemical bonds especially C-O bonding in IR spectrum (Fig. 10), defined the hydrogen of carboxylic acid and alcohol, respectively. Thus, polymerization by an initiator and attaching a terminator to a chain polymer’s end were justified. Then, due to these displacements, the desired product was revealed to be a difunctionalized chain. The details are included in Fig. 989–94.

Figure 10.

IR spectrum of PNIPAAM produced in SC-CO2.

Figure 9.

1HNMR diagram of difunctionalized PNIPAAM.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectrum analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 10, the peak at 3400 cm−1 confirmed the presence of the OH functional group, while the peak at 3300 cm−1 identified the amide functional group. Both of them created two valleys adjacent to one another. The carbonyl group appeared at 1700 cm−1. Carbonyl absorption adjacent to the OH group established the presence of carboxylic acid. Furthermore, the absorption at 1000 cm−1 confirmed the presence of C–O, indicating the presence of a radical attached to the hydroxy TEMPO compound. A weak absorption near 2000 cm−1 demonstrates the presence of nitrile in the initiator formula. Two absorption peaks at 1300 and 1500 cm−1 indicate the connection between N–O and the polymer chain89.

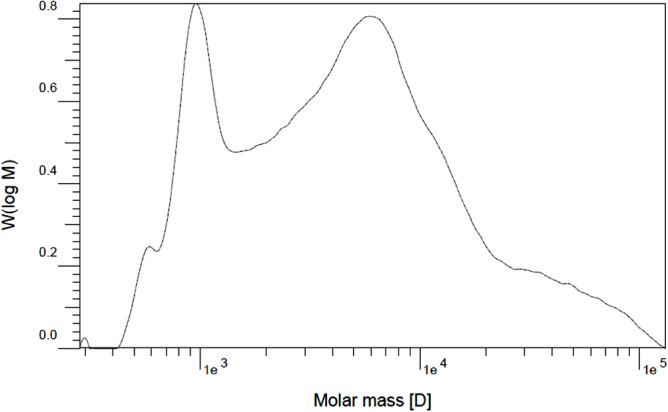

Molecular weight distribution

The molecular mass distribution chromatograms for PNIPAAM are shown in Figs. 11 and 12. Two summits appeared in the diagram under this synthesis condition, and the polydispersity index (PDI) values were broad. The first diagram depicts the polymerization at a pressure of 23 MPa, while the second depicts the polymerization at 20 MPa. For pressures of 23 MPa and 20 MPa, respectively, the PDI values are 2.6 and 3.96. Both PDI values are within the range of radical polymerization; the PDI value is dependent on the polymerization conditions, reaction mechanism, and subsequent environmental history of the polymer94. For polymerization in SC-CO2, pressure is an important parameter because of its effect on the density of the solvent. Increased pressure results in increased density and solubility of materials and a more homogeneous polymerization phase; as a result, the probability of chains with different weights existing is reduced, and the polydispersity becomes narrower76. In addition, higher solubility of terminator at the pressure of 23 MPa led to produce polymer chains with lower molecular weight.

Figure 11.

GPC chromatogram of PNIPAAM produced in SC-CO2 at P = 23 MPa during 6 h, T = 70 °C, Wi/Wm = 1.5%, Wt/Wi = 83.3%, Mw = 4368 (gr/mol), Mn = 1680 (gr/mol) PDI = 2.6, and Mp = 914.5 (gr/mol).

Figure 12.

GPC chromatogram of PNIPAAM produced in SC-CO2 at P = 20 MPa during 6 h, T = 70 °C, Wi/Wm = 1.5%, Wt/Wi = 83.3%, Mw = 9326.5 (gr/mol), Mn = 2355 (gr/mol) PDI = 3.96, and Mp = 956.8 (gr/mol).

Effects of different variables of the linear precursor polymerization reaction

Effect of pressure

Two pressure levels (20 and 23 MPa) were considered to study the effect of pressure. According to previous researches, the polymerization reaction below 10 MPa has no yield. Because the monomer is solid, it is insoluble in the SC-CO2 at these pressures76,77. Then considering the yield, the optimum pressure was 23 MPa. As the most important effect of the pressure is manifested in the solvent density, changes in the pressure alter the liquid properties of the solvent, the solubility of components, effective collision among materials, agitation, and the life time of the radicals in the solvent is resulting in increased yield and a narrower polydispersity21,75–77,95. Another finding was the terminator’s solubility. Due to the low solvent density at lower pressures, the solubility of hydroxyl TEMPO was low; thus, effective collisions between chains and terminators reduced. As a result, the polymer’s Mw value increased. Table 4 contains further details in this regard.

Table 4.

The effect of SC-CO2 pressure on the linear precursor synthesis T = 70 °C Wi/Wm = 1.5%, Wt/Wi = 83.3%, and time = 6 h.

| Pressure (MPa) | Yield (% of converted monomer) | Mn (gr/mol) | Mw (gr/mol)a | Product morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 36% | 2355 | 9326 | Glassy powder |

| 23 | 64% | 1680 | 4368 | Glassy solid gel |

aMolecular weight measured with GPC.

Effect of time

The effect of polymerization time was investigated between 6 and 16 h. Below 6 h the reaction did not have noticeable yield and the polymer was not in the form of powder, but it was in the form of light gel. Since this polymerization process is classified as active radical polymerization, the time parameter can significantly affect the yield. On the other hand, due to the reaction is endothermic, the pressure of SC-CO2 decreased (about 2 MPa) for an extended period (longer than 8 h), necessitating compensation. Pressure fluctuations decreased the solubility of materials, which resulted in a decrease in yield and Mw due to decrease in the monomer participated in to the reaction. Because of the longer radical lifetimes in SC-CO2 media21, the longer reaction time increased the probability of the presence of different molecular weight chains, resulting in the broad polydispersity. But the PDI values were within the radical polymerization range96. As shown in Table 5, the maximum monomer conversion yield was 64% for the time of 6 h.

Table 5.

The effect of time on the linear precursor synthesis.

| Time (h) | Pressure (MPa) | Yield (% of converted monomer ) | Mn (gr/mol) | Mw (gr/mol) | PDI | Product morphology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | 23 | 64% | 1680 | 4368 | 2.6 | Glassy solid gel |

| 12 | 23 | 58.5% | 1488 | 4165 | 2.8 | Glassy puffy powder |

| 16 | 23 | 40% | * | * | * | Glassy powder |

Characterization of cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy spectrum analysis

As illustrated in Figs. 13 and 14, for both cyclic polymers synthesized via distinct reactions, the OH (3400 cm−1) peak nearly vanished; additionally, the 3300 cm−1 peak associated with the amide group became shorter. The peak of C=O was slightly displaced. This evidence confirmed the formation of cyclic polymer and lactone ring89.

Figure 13.

IR spectrum of cPNIPAAM produced in emulsion of SC-CO2 in water.

Figure 14.

IR spectrum of cPNIPAAM produced in homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and DMF co-solvent.

The viscosity average molecular weight measurement

Mv values for cPNIPAAM were approximately 2700 and 3400 gr/mol after lyophilization and solvent elimination via Mark-Houwink equation estimation for emulsion reaction and reaction in SC-CO2 solvent and DMF co-solvent, respectively. These results are acceptable when the linear chain’s mass (Mw = 4165 gr/mol), separated water and the relation between different measured molecular weights (Mn < Mv < Mw) are considered14. Additionally, the intrinsic viscosity values indicated that the polymer produced in the emulsion condition had a lower viscosity average molecular weight than the polymer produced in the homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and DMF co-solvent. This result was obtained from the porosity volume of the polymer generated during the emulsion reaction.

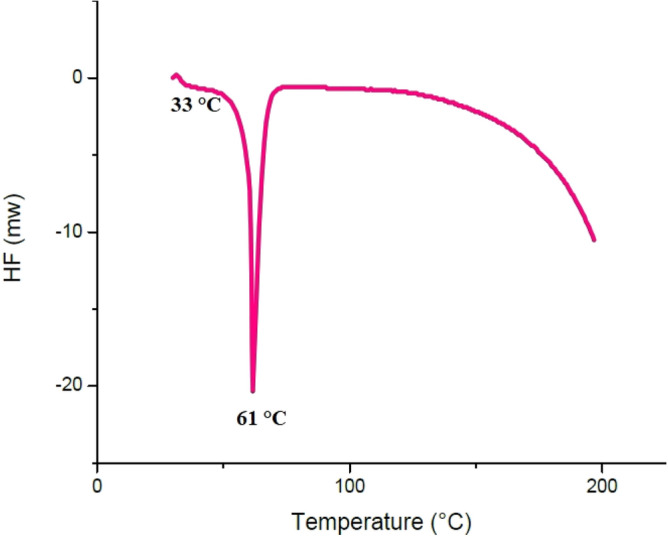

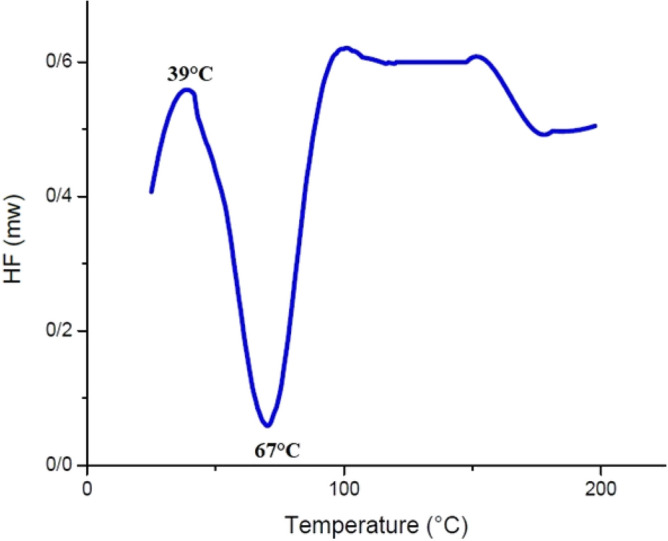

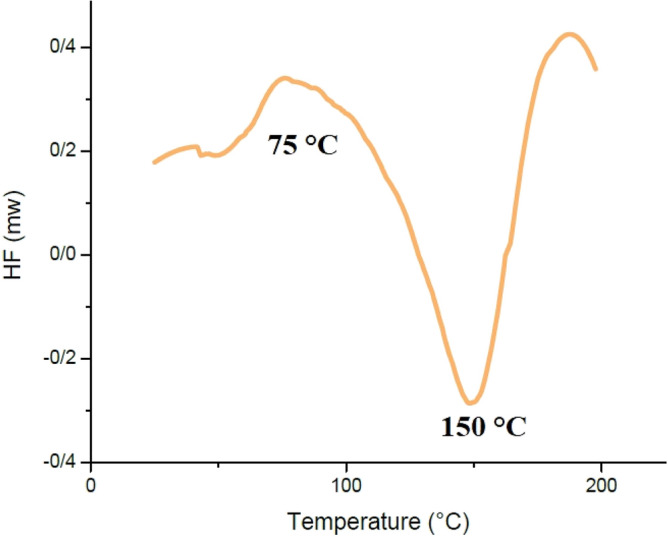

Differential scanning calorimetry analysis

As illustrated in Fig. 15, the Tg of difunctionalized PNIPAAM (Mw = 4165 gr/mol) was 33 °C, with a melting point of 61 °C. The polymer begins to decompose at 140 °C. The DSC curve is identical to that of crystalline polymers.

Figure 15.

DSC diagram of difunctionalized PNIPAAM (Mw = 4165 gr/mol).

Figure 16 indicates that the Tg of cPNIPAAM synthesized via an emulsion reaction was approximately 39 °C and that it melted at 67 °C. These parameters were Tg = 75 °C and Tm = 150 °C for cPNIPAAM synthesized in the homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and DMF (see Fig. 17). The DSC curves matched the crystalline structures.

Figure 16.

DSC diagram of cPNIPAAM synthesized by emulsion reaction.

Figure 17.

DSC diagram of cPNIPAAM produced in a homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and co-solvent of DMF.

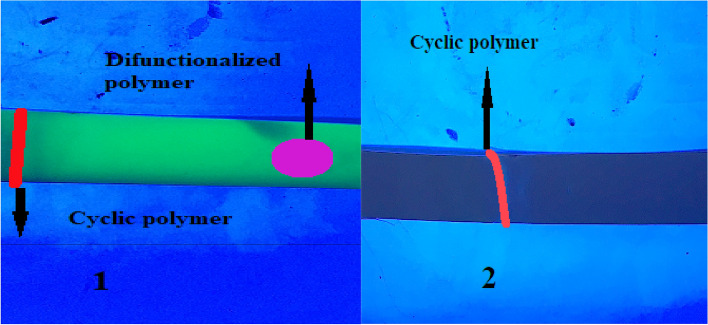

Thin layer chromatography results

Polar molecules separated more quickly here due to the polarity of the stationary phase. As illustrated in Fig. 18, for the cPNIPAAM produced in an emulsion of SC-CO2 and water, the cyclization of the difunctionalized precursor was not complete, and some of them remained. Cyclization in the homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and DMF co-solvent converted all difunctionalized chains to lactone rings, increasing the cyclization yield to nearly 100%, because there is no amount of difunctionalized chains.

Figure 18.

(1) TLC of cPNIPAAM produced in emulsion of SC-CO2 in water; (2) TLC of cPNIPAAM produced by cyclization in homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and DMF.

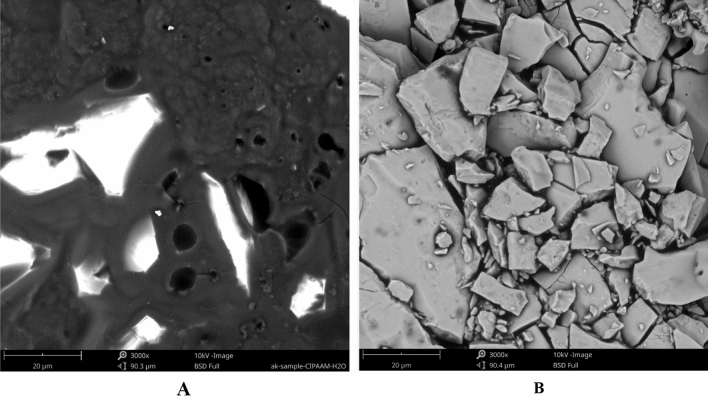

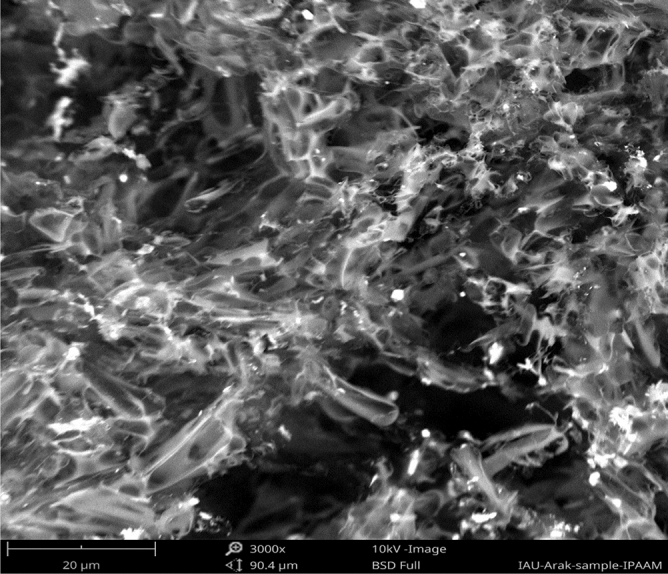

Scanning electron microscopy image of polymers

As shown in Fig. 19, the difunctionalized polymer exhibited a puffy porous structure. The cyclic polymer formed regular blocks in the homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and DMF co-solvent. The cPNIPAAM formed in an emulsion of SC-CO2 and water also had a regular structure but was less dense. Additionally, porosity was evident due to the emulsion reaction (Fig. 20). Thus, the homogeneous reaction produced a stronger cPNIPAAM than the emulsion reaction produced; consequently, it had higher thermal parameters and Mv.

Figure 19.

SEM image of difunctionalized PNIPAAM with magnification 3000.

Figure 20.

SEM image of cyclic polymers with magnification 3000. (A) cPNIPAAM produced in emulsion of SC-CO2 in water; (B) cPNIPAAM produced by cyclization in homogeneous phase of SC-CO2 and DMF.

Advantage of polymerization and cyclization in supercritical carbon dioxide

The organic solvent was omitted from the polymerization of NIPAAM to produce linear precursors. Then a pure polymer was obtained, resulting in a more environmentally friendly process and product. Besides the polymers produced by this solvent have the lower molecular weight and of course lower Tg and melting point in the form of crystalline polymers. Thus, these polymers are noticeable for biomedical purposes, especially drug delivery. As applying moderate pressure leads to reasonable yield in short time of reaction; it is another advantage of this method.

In addition, cyclization reaction by this solvent (SC-CO2) implemented to achieve cyclization yield about 100% at a moderated pressure of 18.5 MPa, and reduced consumption amount of organic solvent. Emulsion reaction was also carried out in water as clean and human safe solvent, increased the porosity of the polymer. Both cyclic polymers are in the form of regular blocks and classified in crystalline polymer that improved the specifications of them, resulting in interesting properties for drug delivery97.

Conclusion

cPNIPAAM was synthesized in SC-CO2 via a homogeneous reaction with a co-solvent of DMF and in a SC-CO2 emulsion in water. Initially, - difunctionalized precursor was synthesized via precipitation polymerization in SC-CO2 solvent. Solvent pressure and polymerization time were critical parameters in this process. Given to the nature of the reaction (endothermic), over a longer period, pressure fluctuation occurred, necessitating compensation; as a result, the yield and molecular weight decreased while the PDI broadened. Additionally, increased pressure increased the solubility of materials, particularly terminators, resulting in a decrease in molecular weight, a narrower polydispersity, and a higher yield. Cyclization in the homogeneous phase with SC-CO2 as solvent and DMF as co-solvent resulted in the formation of regular polymer blocks with increased Mv. The cyclization yield was also 100% at 18.5 MPa pressure in the homogeneous phase. On the other hand, the emulsion reaction of SC-CO2 in water resulted in a prose polymer with a lower Mv, Tg, and Tm.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to take this opportunity to appreciate the Research Deputy to the University of Kashan for financially supporting this research under the Grant code of Pajoohaneh-1401/05.

Abbreviations

- ATRP

Atom transfer radical polymerization

- cPNIPAAM

Cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)

- DMF

Dimethylformamide

- DMSO

Dimethyl sulphoxide

- DSC

Differential scanning calorimetry

- FTIR

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

- GPC

Gel permeation chromatography

- 1HNMR

Hydrogen nuclear magnetic resonance

- LCST

Lower critical solution temperature

- Mn

The number average molecular weight

- Mv

The viscosity average molecular weight

- Mw

Weight average molecular weight

- NIPAAM

N-isopropylacrylamide

- PNIPAAM

Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)

- PDI

Polydispersity index

- RAFT

Reversible addition–fragmentation chain transfer

- Tg

Glass transition temperature

- THF

Tetra hydro furan

- TLC

Thin layer chromatography

- Tm

Melting point

- Wi

Weight of initiator

- Wm

Weight of monomer

- Wp

Weigh of linear polymer

- Wpi

Weight of 2-chloro-1-methylpyridinium iodide

- Wt

Weight of terminator

- Wtea

Weight of triethylamine

Author contributions

S.D.: methodology, investigation, software, writing—original draft; G.S.: conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, supervision, project administration, writing—review and editing, resources.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidential cases are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Schmaljohann D. Thermo-and pH-responsive polymers in drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2006;58:1655–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venkataraman S, Hedrick JL, Ong ZY, Yang C, Ee PL, Hammond PT, Yang YY. The effects of polymeric nanostructure shape on drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2011;63:1228–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Champion JA, Mitragotri S. Role of target geometry in phagocytosis. PNAS. 2006;103:4930–4934. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600997103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang Y, Grayson SM. Approaches for the preparation of non-linear amphiphilic polymers and their applications to drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2012;64:852–865. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kricheldorf HR. Cyclic polymers: Synthetic strategies and physical properties. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym. Chem. 2010;48:251–284. doi: 10.1002/pola.23755. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nasongkla N, Chen B, Macaraeg N, Fox ME, Fréchet JMJ, Szoka FC. Dependence of pharmacokinetics and biodistribution on polymer architecture: Effect of cyclic versus linear polymers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3842–3843. doi: 10.1021/ja900062u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen B, Jerger K, Fréchet JMJ, Szoka FC., Jr The influence of polymer topology on pharmacokinetics: Differences between cyclic and linear PEGylated poly (acrylic acid) comb polymers. J. Control. Release. 2009;140:203–209. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu XY, Liu MZ, Wei H. Recent progress on cyclic polymers: Synthesis, bioproperties, and biomedical applications. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym Chem. 2016;54:1447–1458. doi: 10.1002/pola.28051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu XP, Tanaka F, Winnik FM. Temperature-induced phase transition of well-defined cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide)s in aqueous solution. Macromolecules. 2007;40:7069–7071. doi: 10.1021/ma071359b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin EJ, Jeong W, Brown HA, Koo BJ, Hedrick JL, Waymouth RM. Crystallization of cyclic polymers: Synthesis and crystallization behavior of high molecular weight cyclic poly (ε-caprolactone) s. Macromolecules. 2011;44:2773–2779. doi: 10.1021/ma102970m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bannister D, Semlyen J. Studies of cyclic and linear poly (dimethyl siloxanes): 6. Effect of heat. Polymer. 1981;22:377–381. doi: 10.1016/0032-3861(81)90050-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Xu J, Ye J, Liu S. Synthesis of well-defined cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) via click chemistry and its unique thermal phase transition behavior. Macromolecules. 2007;40:9103–9110. doi: 10.1021/ma0717183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeish T. Polymers without beginning or end. Science. 2002;297:2005–2006. doi: 10.1126/science.1076810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Semlyen JA. Cyclic Polymers. Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kobayashi S. New Frontiers in Polymer Synthesis. Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoskins JN, Grayson SM. Synthesis and degradation behavior of cyclic poly (ε-caprolactone) Macromolecules. 2009;42:6406–6413. doi: 10.1021/ma9011076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu B, Wang H, Zhang LL, Yang G, Liu X, Kim I. A facile approach for the synthesis of cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) based on an anthracene–thiol click reaction. Polym. Chem. 2013;4:2428–2431. doi: 10.1039/c3py00184a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kankala RK, Zhang YS, Wang SB, Lee CH, Chen AZ. Supercritical fluid technology: An emphasis on drug delivery and related biomedical applications. Adv. Health. Mater. 2017;6:1700433. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201700433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kompella UB, Koushik K. Preparation of drug delivery systems using supercritical fluid technology. Crit. Rev. Ther. Drug Carrier Syst. 2001;18:173–199. doi: 10.1615/CritRevTherDrugCarrierSyst.v18.i2.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haddleton AJ, Bassett SP, Howdle SM. Comparison of polymeric particles synthesised using scCO2 as the reaction medium on the millilitre and litre scale. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2020;160:104785. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2020.104785. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boyère BC, Jérôme C, Debuigne A. Input of supercritical carbon dioxide to polymer synthesis: An overview. Eur. Polym. J. 2014;61:45–63. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2014.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sodeifian G, Ansari K. Optimization of Ferulago Angulata oil extraction with supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2011;57:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2011.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS. Experimental optimization and mathematical modeling of the supercritical fluid extraction of essential oil from Eryngium billardieri: Application of simulated annealing (SA) algorithm. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2017;127:146–157. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS. Optimization of essential oil extraction from Launaea acanthodes Boiss: Utilization of supercritical carbon dioxide and cosolvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2016;116:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2016.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS. Supercritical fluid extraction of omega-3 from Dracocephalum kotschyi seed oil: Process optimization and oil properties. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2017;119:139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2016.08.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sodeifian G, SaadatiArdestani NS, Sajadian SA, Moghadamian K. Properties of Portulaca oleracea seed oil via supercritical fluid extraction: Experimental and optimization. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2018;135:34–44. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.12.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS. Evaluation of the response surface and hybrid artificial neural network-genetic algorithm methodologies to determine, extraction yield of Ferulago angulata through supercritical fluid. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2016;60:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jtice.2015.11.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sodeifian G, Hazaveie SM, Sodeifian F. Determination of Galantamine solubility (an anti-alzheimer drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide (CO2): Experimental correlation and thermodynamic modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;330:115695. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115695. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, Razmimanesh F, Hazaveie SM. Solubility of Ketoconazole (antifungal drug) in SC-CO2 for binary and ternary systems: Measurements and empirical correlations. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:7546. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-87243-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sodeifian G, Garlapati C, Razmimanesh F, Sodeifian F. Solubility of amlodipine besylate (calcium channel blocker drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Measurement and correlations. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2021;66:1119–1131. doi: 10.1021/acs.jced.0c00913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sodeifian G, SaadatiArdestani NS, Razmimanesh F, Sajadian SA. Experimental and thermodynamic analyses of supercritical CO2-Solubility of minoxidil as an antihypertensive drug. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2020;522:112745. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2020.112745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hazaveie SM, Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. Measurement and thermodynamic modeling of solubility of Tamsulosin drug (anti-cancer and anti-prostatic tumor activity) in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2020;163:104875. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2020.104875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sodeifian G, Garlapati C, Hazaveie SM, Sodeifian F. Solubility of 2,4,7-triamino-6-phenylpteridine (triamterene, diuretic drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental data and modeling. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2020;65:4406–4416. doi: 10.1021/acs.jced.0c00268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sodeifian G, SaadatiArdestani NS, Sajadian SA, Golmohammadi MR, Fazlali AR. Prediction of solubility of sodium valproate in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental study and thermodynamic modeling. Chem. Eng. Data. 2020;65:1747–1760. doi: 10.1021/acs.jced.9b01069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, Derakhsheshpour R. Experimental measurement and thermodynamic modeling of Lansoprazole solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide: Application of SAFT-VR EoS. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2020;507:112422. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2019.112422. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sodeifian G, Razmimanesh F, SaadatiArdestani NS, Sajadian SA. Experimental data and thermodynamic modeling of solubility of Azathioprine, as an immunosuppressive and anti-cancer drug, in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;299:112179. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.112179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sodeifian G, Razmimanesh F, Sajadian SA, Hazaveie SM. Experimental data and thermodynamic modeling of solubility of Sorafenib tosylate, as an anti-cancer drug, in supercritical carbon dioxide: Evaluation of Wong-Sandler mixing rule. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2020;142:105998. doi: 10.1016/j.jct.2019.105998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sodeifian G, Razmimanesh F, Sajadian SA. Prediction of solubility of sunitinib malate (an anti-cancer drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide (SC–CO2): Experimental correlations and thermodynamic modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2020;297:111740. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2019.111740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sodeifian G, Derakhsheshpour R, Sajadian SA. Experimental study and thermodynamic modeling of Esomeprazole (proton-pump inhibitor drug for stomach acid reduction) solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2019;154:104606. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2019.104606. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sodeifian G, Hazaveie SM, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS. Determination of the solubility of the repaglinide drug in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental data and thermodynamic modeling. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2019;64:5338–5348. doi: 10.1021/acs.jced.9b00550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sodeifian G, Hazaveie SM, Sajadian SA, Razmimanesh F. Experimental investigation and modeling of the solubility of oxcarbazepine (an anticonvulsant agent) in supercritical carbon dioxide. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2019;493:160–173. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2019.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. Experimental measurement of solubilities of sertraline hydrochloride in supercriticalcarbon dioxide with/without menthol: Data correlation. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2019;149:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2019.03.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sodeifian G, Razmimanesh F, Sajadian SA, SoltaniPanah HR. Solubility measurement of an antihistamine drug (Loratadine) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Assessment of qCPA and PCP-SAFT equations of state. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2018;472:147–159. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2018.05.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. Solubility measurement and preparation of nanoparticles of an anticancer drug (Letrozole) using rapid expansion of supercritical solutions with solid cosolvent (RESS-SC) J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2018;133:239–252. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.10.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sodeifian G, SaadatiArdestani NS, Sajadian SA, SoltaniPanah HR. Measurement, correlation and thermodynamic modeling of the solubility of Ketotifen fumarate (KTF) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Evaluation of PCP-SAFT equation of state. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2018;458:102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2017.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sodeifian G, SaadatiArdestani NS, Razmimanesh F. Solubility of an antiarrhythmic drug (amiodarone hydrochloride) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental and modeling. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2017;450:149–159. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2017.07.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS. Determination of solubility of Aprepitant (an antiemetic drug for chemotherapy) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Empirical and thermodynamic models. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2017;128:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2017.05.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sodeifian G, Hsieh CM, Derakhsheshpour R, Chen YM, Razmimanesh F. Measurement and modeling of metoclopramide hydrochloride (anti-emetic drug) solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide. Arab. J. Chem. 2022;15:103876. doi: 10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.103876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sodeifian G, Garlapati C, Razmimanesh F, Nateghi H. Experimental solubility and thermodynamic modeling of Empagliflozin in supercritical carbon dioxide. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:9008. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-12769-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sodeifian G, Garlapati C, Razmimanesh F, Nateghi H. Solubility measurement and thermodynamic modeling of Pantoprazole sodium sesquihydrate in supercritical carbon dioxide. Sci. Rep. 2022;12:7758. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-11887-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sodeifian G, Nasri L, Razmimanesh F, Abadian MA. CO2 utilization for determining solubility of teriflunomide (immunomodulatory agent) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental investigation and thermodynamic modeling. J. CO2 Util. 2022;58:101931. doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2022.101931. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sodeifian G, SuryaAlwi R, Razmimanesh F. Solubility of Pholcodine (antitussive drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental data and thermodynamic modeling. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2022;556:113396. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2022.113396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sodeifian G, Surya Alwi R, Razmimanesh F, Abadian MA. Solubility of Dasatinib monohydrate (anticancer drug) in supercritical CO2: Experimental and thermodynamic modeling. J. Mol. Liq. 2022;346:117899. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.117899. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sodeifian G, Garlapati C, Razmimanesh F, Ghanaat-Ghamsari MS. Measurement and modeling of clemastine fumarate (antihistamine drug) solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:24344. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03596-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sodeifian G, Garlapati C, Razmimanesh F, Sodeifian F. The solubility of Sulfabenzamide (an antibacterial drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Evaluation of a new thermodynamic model. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;335:16446. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.116446. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sodeifian G, SuryaAlwi R, Razmimanesh F, Tamura K. Solubility of Quetiapine hemifumarate (antipsychotic drug) in supercritical carbon dioxide: Experimental, modeling and Hansen solubility parameter application. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2021;537:113003. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2021.113003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sodeifian G, Nasri L, Razmimanesh F, Abadian MA. Measuring and modeling the solubility of an antihypertensive drug (losartan potassium, Cozaar) in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Mol. Liq. 2021;331:115745. doi: 10.1016/j.molliq.2021.115745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, Derakhsheshpour R. CO2 utilization as a supercritical solvent and supercritical antisolvent in production of sertraline hydrochloride nanoparticles. J. CO2 Util. 2022;55:101799. doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2021.101799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Razmimanesh F, Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. An investigation into Sunitinib malate nanoparticle production by US-RESOLV method: Effect of type of polymer on dissolution rate and particle size distribution. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2021;170:105163. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2021.105163. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS, Razmimanesh F. Production of Loratadine drug nanoparticles using ultrasonic-assisted rapid expansion of supercritical solution into aqueous solution (US-RESSAS) J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2019;147:241–253. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2018.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, SaadatiArdestani NS, SoltaniPanah H. Experimental measurements and thermodynamic modeling of Coumarin-7 solid solubility in supercritical carbon dioxide: Production of nanoparticles via RESS method. Fluid Ph. Equilibria. 2019;483:122–143. doi: 10.1016/j.fluid.2018.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. Utilization of ultrasonic-assisted RESOLV (US-RESOLV) with polymeric stabilizers for production of amiodarone hydrochloride nanoparticles: Optimization of the process parameters. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2019;142:268–284. doi: 10.1016/j.cherd.2018.12.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA, Daneshyan S. Preparation of Aprepitant nanoparticles (efficient drug for coping with the effects of cancer treatment) by rapid expansion of supercritical solution with solid cosolvent (RESS-SC) J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2018;140:72–84. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2018.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.SaadatiArdestani NS, Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. Preparation of phthalocyanine green nano pigment using supercritical CO2 gas antisolvent (GAS): Experimental and modeling. Heliyon. 2020;6:e04947. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ameri A, Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. Lansoprazole loading of polymers by supercritical carbon dioxide impregnation: Impacts of process parameters. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2020;164:104892. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2020.104892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fathi M, Sodeifian G, Sajadian SA. Experimental study of ketoconazole impregnation into polyvinyl pyrrolidone and hydroxyl propyl methyl cellulose using supercritical carbon dioxide: Process optimization. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2022;188:105674. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2022.105674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sodeifian G, BehvandUsefi MM. Solubility, extraction, and nano particles production in supercritical carbon dioxide: A mini-review. Chem. Bio. Eng. Rew. 2022 doi: 10.1002/cben.202200020.R1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oliveira ELG, Silvestre AJD, Silva CM. Review of kinetic models for supercritical fluid extraction. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2011;89:1104–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.cherd.2010.10.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bonavoglia B, Storti G, Morbidelli M, Rajendran A, Mazzotti M. Sorption and swelling of semicrystalline polymers in supercritical CO2. J. Polym Sci. 2006;44:1531–1546. doi: 10.1002/polb.20799. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kazarian S. Polymer processing with supercritical fluids. J. Polym. Sci. Ser. C. 2000;42:78–101. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker TA, Frankowski DJ, Spontak RJ. Thermodynamics and kinetic processes of polymer blends and block copolymers in the presence of pressurized carbon dioxide. Adv. Mater. 2008;20:879–898. doi: 10.1002/adma.200700076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Picchioni F. Supercritical carbon dioxide and polymers: An interplay of science and technology. Polym. Int. 2014;63:1394–1399. doi: 10.1002/pi.4722. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Mase N, Yamamoto S, Nakaya Y, Sato K, Narumi T. Organocatalytic stereoselective cyclic polylactide synthesis in supercritical carbon dioxide under plasticizing conditions. Polymers. 2018;10:713–721. doi: 10.3390/polym10070713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Daneshyan S, Sodeifian GH. Synthesis of cyclic polystyrene in supercritical carbon dioxide green solvent. J. Supercrit. Fluids. 2022;188:105679. doi: 10.1016/j.supflu.2022.105679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zetterlund PB, Aldabbagh F, Okubo M. Controlled/living heterogeneous radical polymerization in supercritical carbon dioxide. J. Polym. Sci. Part A Polym Chem. 2009;47:3711–3728. doi: 10.1002/pola.23432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hu Y, Cao L, Xiao F, Wang J. Synthesis of thermoresponsive microgels in supercritical carbon dioxide using ethylene glycol dimethacrylate as a crosslinker. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2010;21:386–391. doi: 10.1002/pat.1440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Cao LQ, Chen LP, Jiao JQ, Zhang SY, Gao W. Synthesis of cross-linked poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) microparticles in supercritical carbon dioxide. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2007;285:1229–1236. doi: 10.1007/s00396-007-1675-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ryana J, Aldabbagha F, Zetterlundb PB, Okubob M. First nitroxide-mediated free radical dispersion polymerizations of styrene in supercritical carbon dioxide. Polymer. 2005;46:9769–9777. doi: 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.08.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Said-Galiyev EE, Pototskaya IV, Vygodskii YS. Supercritical carbon dioxide and polymers. Polym. Sci Series C. 2004;46:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Duran-Valencia C, Valtz A, Galicia-Luna LA, Richon D. Isothermal vapor−liquid equilibria of the carbon dioxide (CO2)-n,n-dimethylformamide (DMF) system at temperatures from 293.95 K to 338.05 K and pressures up to 12 MPa. J. Chem. Eng. Data. 2001;46:1589–1592. doi: 10.1021/je010055w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Aldrich cataloge NO. Z412473, Application:free radical initiators, https://www.sigmaaldrich.com.

- 82.L. outsuka chemical co, Azo series. https://www.otsukac.co.jp/en/products/chemical/azo.

- 83.Mukaiyama T, Usui M, Saigo K. The facile synthesis of lactones. Chem. Lett. 1976;5:49–50. doi: 10.1246/cl.1976.49. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lepoittevin B, Perrot X, Masure M, Hemery P. New route to synthesis of cyclic polystyrenes using controlled free radical polymerization. Macromolecules. 2001;34:425–429. doi: 10.1021/ma001183c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Juttulapa M, Piriyaprasarth S, Takeuchi H, PornsakSriamornsak P. Effect of high-pressure homogenization on stability of emulsions containing zein and pectin. Pharm. Sci. 2017;12:21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ganachaud F, Monteiro MJ, Gilbert RG, Dourges MA, Thang SH, Rizzardo E. Molecular weight characterization of poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) prepared by living free-radical polymerization. Macromolecules. 2000;33:6738–6745. doi: 10.1021/ma0003102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Benmounaa M, Maschke U. Theoretical aspects of cyclic polymers: effects of excluded volume interactions. In: Semlyen JA, editor. Cyclic Polymers. Springer; 2002. pp. 741–788. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hatakeyama T, Quinn FX. Thermal Analysis: Fundamental and Application to Polymer Science. 2. Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pavia D, Lampman G, Kris G. Introduction to Spectroscopy: A Guide for Students of Organic Chemistry. 3. Belmont Brooks/Cole; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Haseloh S, van der Schoot P, Zentel R. Control of mesogen configuration in colloids of liquid crystalline polymers. Soft Matter. 2010;6:4112. doi: 10.1039/c0sm00125b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mitsukami Y, Donovan MS, Lowe AB, McCormick CL. Water-soluble polymers. 81. Direct synthesis of hydrophilic styrenic-based homopolymers and block copolymers in aqueous solution via RAFT. Macromolecules. 2001;34:2248–2256. doi: 10.1021/ma0018087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Chen J, Tan S, Gao G, Lib H, Zhang Z. Synthesis and characterization of thermally selfcurable fluoropolymer triggered by TEMPO in one pot for high performance rubber applications. Polym. Chem. 2014;5:2130. doi: 10.1039/c3py01390a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Veerapandian S, Sultan Nasar A. Successful synthesis of distinct dendritic unimolecular initiators suitable for topologically attractive star polymers. RSC Adv. 2015;5:23034. doi: 10.1039/C5RA02352A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Qiu XP, Tanaka F, Winnik FM. Temperature-induced phase transition of well-defined cyclic poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) in aqueous solution. Macromolecules. 2007;40:7069–7071. doi: 10.1021/ma071359b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kamrupi IR, Pokhrel B, Kalita A, Boruah M, Dolui SK, Boruah R. Synthesis of macroporous polymer particles by suspension polymerization using supercritical carbon dioxide as a pressure adjustable porogen. Adv. Polym. Technol. 2011;31:154–162. doi: 10.1002/adv.20246. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ward TC. Molecular weight and molecular weight distributions in synthetic polymers. J. Chem. Educ. 1981;58:867–879. doi: 10.1021/ed058p867. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kaczmarek B, Sionkowska A. Drug release from porous matrixes based on natural polymers. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2017;18:721–729. doi: 10.2174/1389201018666171103141347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to confidential cases are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.