Abstract

Modern studies of lithium-ion battery (LIB) cathode materials employ a large range of experimental and theoretical techniques to understand the changes in bulk and local chemical and electronic structures during electrochemical cycling (charge and discharge). Despite its being rich in useful chemical information, few studies to date have used 17O NMR spectroscopy. Many LIB cathode materials contain paramagnetic ions, and their NMR spectra are dominated by hyperfine and quadrupolar interactions, giving rise to broad resonances with extensive spinning sideband manifolds. In principle, careful analysis of these spectra can reveal information about local structural distortions, magnetic exchange interactions, structural inhomogeneities (Li+ concentration gradients), and even the presence of redox-active O anions. In this Perspective, we examine the primary interactions governing 17O NMR spectroscopy of LIB cathodes and outline how 17O NMR may be used to elucidate the structure of pristine cathodes and their structural evolution on cycling, providing insight into the challenges in obtaining and interpreting the spectra. We also discuss the use of 17O NMR in the context of anionic redox and the role this technique may play in understanding the charge compensation mechanisms in high-capacity cathodes, and we provide suggestions for employing 17O NMR in future avenues of research.

1. Motivation

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) play a critical role in enabling future sustainable energy sources by storing energy for grid usage and powering devices and transportation.1−3 To ensure that electric vehicles (EVs) powered with LIB technologies are competitive with those that use fossil-fuel energy sources, LIB components must be low-cost and environmentally sustainable (ideally, fully recyclable)4 while also achieving high capacities over long lifetimes. At present, a major bottleneck to high capacities, long lifetimes, and cost is the cathode.5 As such, multiple research initiatives have sought to identify, develop, and optimize cathode materials to improve the electrochemical performance of LIBs.

2. Introduction

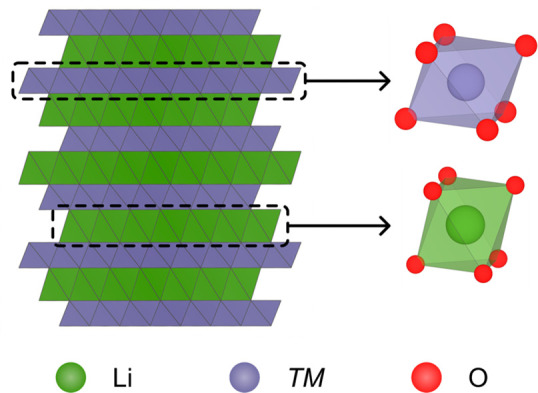

Layered LIB cathodes, with a general formula LiTMO2 (TM = transition metal), are perhaps the most promising class of cathode materials currently available and, with related materials, are the focus of this Perspective.5−13 Here, edge-sharing TMO6 octahedra are arranged into “TMO2” layers, with Li+ cations in the interlayer spaces [Figure 1]. The structures are commonly described according to the notation used by Delmas et al.:14 a letter denoting the coordination environment of Li+ (O for octahedral, T for tetrahedral, and P for prismatic) and a number describing how many distinct TMO2 layers there are per unit cell. For example, O3 describes a layered cathode with octahedrally coordinated Li+ ions and three distinct layers per unit cell. A second notation uses the crystallographic symmetry of the cell, the number denoting the order in which the phase is found on cycling the battery. For example, on delithiating pristine LiCoO2, an O3 phase in Delmas notation or H1 (hexagonal) phase in the latter notation, a new O3 phase forms, denoted O3′ or H2. Intergrowth phases can similarly form, in which two distinct stacking sequences are combined in an ordered manner, and again both notations are used. For example, H1-3 describes an intergrowth of the O1 and O3 phases.

Figure 1.

Crystal structure of a layered LIB cathode, LiTMO2, with the layers and local TM and Li+ coordination polyhedra highlighted.

To understand the electrochemical properties of the cathode, the bulk and local structural changes that take place during cycling are evaluated, so that a clear picture of the redox mechanisms and phase changes induced during cycling may be constructed. These studies commonly use techniques such as ex situ or operando X-ray diffraction (XRD),15−17 X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS),18−20 and ab initio calculations.21−25 Recent studies of local structure have also used solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, owing to the high natural abundance and receptivity of (in particular) NMR-active 6Li and 7Li nuclei.16,17,26−28 While 17O NMR has proven an invaluable characterization technique in materials chemistry,29−36 and despite oxygen being the primary anion in LIB cathodes, there are, however, comparatively many fewer studies that have used 17O NMR.37−41

In this Perspective, we assess how 17O NMR has been used to understand the local (chemical and electronic) structures of LIB cathodes in both pristine and electrochemically cycled materials. In some cathode materials, capacities exceeding those of conventional TM redox couples and voltages above those of the TM redox couples have been observed. Such capacities have been assigned to redox reactions involving O2– anions (henceforth O or anion redox). We therefore also examine how 17O NMR can help to report the changes in ionicity and covalency of the TM–O bonds during charge and discharge and ultimately provide important clues about the nature of the oxygen species. In order to appreciate the challenges associated with acquiring 17O NMR spectra, we start by discussing some of the practical and theoretical aspects associated with 17O NMR spectroscopy.

3. The Need for Isotopic Enrichment

17O is the only NMR-active nucleus of oxygen. With a natural abundance of 0.037%, enrichment is generally required to achieve a good signal-to-noise ratio.31 Enrichment is expensive, thus 17O NMR should be used judiciously. Syntheses of enriched LIB cathodes can also be challenging, owing to the small scale (typically <100 mg) and the subtle differences in conditions used to prepare them, as compared to “natural-abundance” syntheses. For example, enrichment is often performed either as an annealing step in a static 17O2 gas atmosphere or by heating 17O-enriched starting materials in a static inert atmosphere, while a “normal” synthesis might use air or flowing O2 gas. Hydrothermal methods using H217O have also been employed but require careful optimization.38,42

4. Dominant Interactions in 17O NMR Spectroscopy

4.1. Chemical Shift

The chemical shift, which arises from the shielding of the applied magnetic field by electrons surrounding the nucleus, spans a vast range for 17O (approximately −100 ppm to +2500 ppm43,44); by contrast the 6,7Li chemical shift spans less than 10 ppm. While the chemical shift rarely dominates the observed 17O shifts in LiTMO2 cathodes due to the presence of paramagnetic centers (either as-synthesized or formed on cycling), it may still need to be accounted for in these paramagnetic systems.

4.2. Hyperfine Shift

As alluded to above, perhaps the most important consideration when acquiring 17O NMR of LIB cathode materials is the effect of paramagnetism.26,28 The hyperfine interaction between unpaired electron density (in LiTMO2, unpaired electrons on the TM centers) and nuclear spins in a material generally results in fast nuclear relaxation times, broad signals, and large in magnitude shifts.26,28,45

The large shifts are invariably dominated by the Fermi contact shift, which arises from the interaction between unpaired electronic spin density at the nucleus and the nuclear spin under observation. In practice, this arises from transfer of unpaired electron density from paramagnetic ions to s orbitals on O [Figure 2a,b]. The TMd and O orbitals interact with each other to give fully occupied bonding orbitals (dominated by O orbitals, but still containing some TM character; bottom of Figure 2a) and either empty or partially filled anti-bonding or non-bonding orbitals (dominated by TM orbitals but with some O character, top of Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Illustrations of the hyperfine interaction in NMR. (a) The Fermi contact (through-bond) interaction of unpaired electron density on TM cations with a neighboring O nucleus. The bonding (t2g and eg) and anti-bonding (t2g* and eg*) combinations of TMd orbitals and s or p orbitals on O result in different spin density transfer processes. Bonding combinations cause spin polarization of electrons in filled s orbitals on O, while anti-bonding combinations cause spin delocalization (and polarization, in the case of the t2g* interaction). The sign of the spin density induced at the s orbitals (which defines the Fermi contact shift) is indicated to the right. (b) The interaction of the O nucleus with the nearest-neighbor and next-nearest-neighbor unpaired electron spins in the TMO2 layer (of which there are z1 and z2) of a typical layered LIB cathode. These paths induce hyperfine shifts of δ1 and δ2, respectively, giving a total shift of δtot.

In the case of the bonding combination of t2g and O orbitals, the unpaired electrons in the t2g* orbitals or indeed any TM orbital (whose spin is arbitrarily chosen as “up” in the proceeding argument) polarize(s) the fully occupied orbital such that the spins of electrons circulating nearby the TM center are in the same direction as those on the TM. This interaction is mediated via the exchange interaction, where electrons with the same spin occupy different regions of space, thus reducing the repulsion between them and lowering the energy of the system. Since the electron near the TM is polarized “up”, the nearby O is polarized “down”, because the two electrons occupying this orbital are spin-paired. This in turn polarizes the electrons occupying the s orbitals on O (again via the exchange interaction) such that these s orbitals align anti-parallel to the TM spin. This is denoted “negative” spin density (as it is opposite in sign to the TM, arbitrarily labeled as “positive”). By contrast, if the anti-bonding version of the same (t2g) orbital is partially occupied, then electron density is delocalized directly over the TM and O centers, such that the sign of the electron spin is preserved regardless of which center the electron sits nearer. This again polarizes the s orbitals, but now with “positive” spin density, where the electrons in O s orbitals are preferentially aligned with the TM spins. Note that if this anti-bonding combination is fully occupied, then the same argument as in the bonding combination applies, while if it is vacant, then negligible spin delocalization or polarization occurs.

The TMeg orbitals can overlap directly with the O s orbitals: In the case of the bonding combination, the O s acquires negative spin density (again, from spin pairing), while the anti-bonding combination results in positive spin density, again due to delocalization of an unpaired spin across both centers. Note that in all cases discussed above, O is formally diamagnetic and has a complete outer shell of electrons, while the TM has a partially filled d shell and is (generally) paramagnetic. The polarization of spin density does not alter oxidation states or orbital populations, but merely the distribution (relative populations) of spins. The net unpaired spin at O results in the strong hyperfine interaction.

A robust method for analyzing and assigning the complex spectra of paramagnetic materials is bond pathway analysis, developed originally to analyze 6,7Li and later 31P spectra.46,47 Here, the overall shift of a nucleus is assumed to be given by the sum of the shifts induced by each paramagnetic nearest and next-nearest TM neighbor [Figure 2b]. This generally holds true for LiTMO2 systems.

The individual shift contributions depend on the chemical identity of the TM cation, its oxidation state (which defines the number of electrons and often the degree of covalency or orbital overlap), and the bond angles and distances between the TM cation and nucleus of interest. Deviations of the total shift from this sum occur for significant deviations away from ideal 180° and 90° bond pathways. Interactions either between different TMs, or within the same ion but between the orbital and spin angular momenta, L and S, respectively, can complicate the analysis, and the reader is directed to ref (45) for a more in-depth discussion of these effects. In the case of the latter, when electrons occupy orbitals with (often only partially quenched) orbital angular momentum, L and S couple to give a set of electron spin microstates whose energies are modified from the spin-only picture. This, depending on the site symmetry, can lead to an anisotropic magnetic susceptibility, and in turn a pseudo-contact shift, which also needs to be taken into account.

The temperature dependence of the time-averaged electron spin moment is reflected in the hyperfine shift: as the moment size increases, the magnitude of the shifts increases, too. These shifts may be calculated via hybrid density functional theory (DFT) calculations and rationalized using the Goodenough–Kanamori rules (see later).48−50 Through careful modeling, these complex spectra can be appropriately assigned to reveal valuable information about the local environments in a material.

While bond pathway analysis of 6Li and 7Li NMR spectra is well-established, the situation is more complex for 17O NMR, Since O is directly bonded to TM cations, the shifts induced are generally significantly larger, and the overall shift is often composed of several competing Fermi contact interactions with unpaired spins on several nearby TM cations.40 Typical (calculated) bond pathway shifts for O bound to different paramagnetic centers are shown in Table 1. These shifts can provide considerable insight into local magnetic exchange couplings between TM cations and therefore act as a local handle on the electronic spin density distribution in the material.

Table 1. Nearest-Neighbor 17O Fermi Contact Shift Bond Pathways for Different TM Cations Bound to O and Quadrupolar Coupling Constants, CQ, from Ref (47)a.

| TM–O path | bond pathway (ppm) | ref |

|---|---|---|

| Mn4+–O | 900–1100b | (32) |

| Ni3+–O (long) | 12500 | (108) |

| Ni3+–O (short) | 2300 | (108) |

| fitted CQ (MHz) | calcd CQ (MHz) | ref |

|---|---|---|

| 4.40–4.55 | 4.50–4.60 | (47) |

The Mn4+–O pathways and CQ values were determined for Li2MnO3; the Ni3+–O (long/short) pathways for Li[Ni0.8Co0.15Al0.05]O2.

The bond pathway strongly depends on the bond length and the Mn–O–Mn angle.

An additional, through-space, anisotropic component of the hyperfine interaction, the dipolar hyperfine interaction, contributes to the hyperfine shift observed but is usually smaller than the Fermi contact interaction.45 The dipolar interaction does, however, generate a broad sideband manifold under magic angle spinning (MAS) which spans several thousand ppm, meaning that a single radiofrequency pulse cannot excite the entire spectrum.29,40,41 As a result, variable-offset cumulative spectra (VOCS) experiments are often required to excite the entire spectrum (see the Supporting Information (SI)).51

In addition to a strong hyperfine interaction, the short TM–O distances result in stronger paramagnetic relaxation enhancement than on 6,7Li, leading to short relaxation times (on the order of the receiver deadtime or the echo evolution period). This results in severely broadened resonances which, in the worst-case scenario, may be unobservable or so broad that they are lost in the baseline.

To mitigate the effect of the hyperfine interaction, low magnetic field strengths are preferred, in contrast to the quadrupolar interaction (see later).

4.3. Quadrupolar Interaction

On top of the practical difficulties and large chemical shift ranges, 17O NMR spectroscopy is complicated by the strongly quadrupolar nature of 17O (nuclear spin I = 5/2),31 quantified by the quadrupolar coupling constant, CQ. Even under MAS, a broad spinning sideband manifold is commonly observed—once again making VOCS critical to spectral acquisition—as well as broadening of the central transition (isotropic resonance) and a field-dependent contribution to the chemical shift (known as the quadrupole-induced shift, QIS). For 17O, CQ varies between hundreds of kHz (high-symmetry O sites) and 10s of MHz for more anisotropic environments (e.g., phosphates, peroxides, and organic systems), the magnitude depending on the covalency or ionicity of the local bonding environment: O sites with more covalent TM–O bonds have a larger CQ than ionic TM–O bonds.52

The effect of the quadrupolar interaction may be mitigated by increasing the field strength at which the experiments are performed. However, the Fermi contact interaction and dipolar interactions with the unpaired electrons scale with the field, so performing 17O NMR of paramagnetic solids at high fields is not always possible. In practice, “intermediate” field strengths (e.g., 7–11 T) and fast MAS speeds (“fast” compared to the size of the hyperfine and quadrupolar interactions, typically >50 kHz) have been employed to performed 17O NMR spectroscopy of LIB cathodes. For additional information regarding the effects of the quadrupolar interaction, please see the SI (section S1).

Finally, we note that both the quadrupolar and hyperfine interactions discussed above contribute to the breadth of the observed resonance. Beyond this, additional broadening arises from a distribution of local environments (due to distributions in local bond angles and lengths, often from disorder); small deviations in the pathways can lead to a change in up to 200 ppm for the bond pathway [Table 1]. In general, peak breadth due to a distribution of local environments dominates over the broadening due to relaxation effects due to the interaction, which in turn exceeds the broadening from quadrupolar interactions. This is not always the case, for example, for materials containing Co4+ and Ni2+/3+ paramagnetic ions (see the LiNi0.80Co0.15Al0.05]O2 and LiCoO2 case studies below).

5. Calculating 17O NMR Parameters

To assist the interpretation of 17O NMR, parameters such as the chemical shift, hyperfine shift, and quadrupolar tensors may be calculated.30,40,43 Although the observed resonances are generally severely broadened—making fitting from scratch challenging, with many models giving similar quality fits—fitting the spectrum to an initial model guided by ab initio calculations is often invaluable in spectrum assignment.

Calculation of these parameters in paramagnetic systems such as LIB and sodium ion battery (NIB) cathodes, however, is not straightforward, owing to the strong electron correlation in 3dTM systems. While challenging, however, calculation of quadrupolar and hyperfine NMR parameters of LIB and NIB systems has been successfully completed for a range of materials.29,30,40

The layered TM oxide materials used as LIB and NIB cathodes generally have many local chemical environments—for example, for an O3 layered cathode material with two TM cations occupying the TM sublattice in a disordered or partially ordered array, there exist 42 possible local environments for O2– ions (considering nearest- and next-nearest-neighboring TM cations only). Calculating the shifts of each of these sites is possible but computationally expensive.

Another approach is to use the bond pathway contribution of a TM cation to the nucleus of interest (see above). Here, the Fermi contact shift, δFC, may be decomposed into individual shifts from each TM cation, δpath:

where zi is the number of pathways of type i, with a shift contribution of δpath,i (see Table 1 for examples). Appropriate combinations of these pathways may then be compared to the observed spectra to enable assignment.

The quadrupolar parameters may be extracted from the local electric field gradient (EFG) tensors, V, in a material (for definitions see SI). Hence, the quadrupolar and hyperfine parameters may be readily computed and compared by fitting to the experimental spectrum [Table 1].

6. Applying 17O NMR to Studying LIB Cathodes

While it is challenging to acquire and interpret the spectra, 17O NMR is rich in information about both the local chemical structure of a material (through its quadrupolar interactions) and the local electronic and magnetic structure (through the hyperfine interaction).29−33 In this Perspective, we present a series of published studies on LIB cathodes utilizing 17O NMR, alongside a new study on the 17O NMR of Li[Ni0.8Co0.15Al0.05]O2. Each case study examines a different cathode and aims to use 17O NMR to understand the local structure of the pristine material and/or structural evolution during charge/discharge.

7. 17O NMR as a Tool for Pristine Material Characterization

We first examine how 17O NMR may be used to establish the chemical structure and magnetic properties of pristine cathode materials and illustrate the use of bond pathway analysis.

7.1. Li2MnO3

The first use of 17O NMR to examine a LIB cathode was in 2016 by Seymour et al., where the local O environments of Li2MnO3 were explored and the experimental spectra assigned using ab initio hybrid DFT calculations of the 17O shifts.40

Li2MnO3 adopts a layered structure whose formula can be rewritten as Li[Li1/3Mn2/3]O2, with the Li+ and Mn4+ cations adopting an ordered honeycomb arrangement [Figure 3a]. This compound is highly susceptible to stacking faults, where the [Li1/3Mn2/3]O2 layers may be offset relative to each other; the “ordered” regions correspond to an O3 structure with space group C2/m, while the “faulted” regions retain the O3 structure and are locally analogous to the P3112 Li2MnO3 polymorph [Figure 3a]. The extent of stacking faults depends on the synthesis method.53

Figure 3.

17O NMR spectroscopy of Li2MnO3. (a) Structure of ordered and stacking-faulted Li2MnO3 with honeycomb ordering in the Li1/3Mn2/3 layers, but different stacking sequences and symmetries of these layers. Distinct crystallographic O sites are shown and labeled with their Wyckoff positions. (b) 17O NMR Hahn-echo VOCS slices and sum for a sample of 17O-enriched Li2MnO3 at 11.7 T and a 60 kHz MAS rate. (c) Expansion of the isotropic region of the spectrum, with peaks from the ordered and faulted phases labeled. Adapted with permission from ref (40). Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Seymour et al. enriched a sample of Li2MnO3 using a post-synthetic gas enrichment process and acquired 17O Hahn-echo NMR spectra using VOCS to excite the entire spectrum.40 By examining spectra at different magnetic field strengths, Seymour et al. were able to identify five isotropic resonances (i.e., five unique local 17O environments; Figure 3b,c). These resonances were assigned to specific local environments using bond pathway analysis.

Calculations revealed that the bond pathway shift in both the C2/m and P3112 polymorphs varied with Mn···O distance. In general, however, a single Mn bound directly to O (i.e., the nearest-neighbor Mn to O) gives a shift of +1000 ppm, while Mn indirectly bound to O (i.e., the next-nearest-neighbor Mn to O) contributes approximately +200 ppm. Each unique combination of nearest- and next-nearest-neighbor Mn–O distances (i.e., the unique local environment) results in different shifts for each site.

Based on these bond pathways, two of the observed peaks were assigned to the “ordered” (C2/m) Li2MnO3; crystallographically, these are known as the 4i and 8j sites (Wyckoff labeling), both coordinated to two Mn4+ and one Li+ cation within the Li+ layer, but in different relative positions in the layer. The remaining three were assigned to O environments in the “faulted” (P3112) structure, known as 6c(1), 6c(2), and 6c(3) [Figure 3a,c]. By carefully examining the intensities of the resonances, a 1:2 ratio of the 4i and 8j sites was identified, while the intensity ratios for the stacking fault resonances were approximately 1:1:1, as anticipated from the crystal structure.

This work demonstrated that 17O NMR, in conjunction with ab initio bond pathway calculations, can identify defect structures and subtle differences (i.e., TM···O distances and bond angles) in local environments.

7.2. Li2RuO3

The next study explored the structure and phase transformation of Li2RuO3, whose honeycomb-ordered structure with Li+ and Ru4+ ions in the TMO2 layer (i.e., [Li1/3Ru2/3]O2, Figure 4), well-characterized Ru4+/5+ redox couple, and reversible electrochemistry make this material a good model compound for studying oxygen redox.41 The Ru4+ cations adopt an ordered array of Ru–Ru dimers with short Ru–Ru distances (generated from direct overlap of the Ru 4d orbitals), in addition to long and medium distances [Figure 4a].54 The dimerization affects the magnetic susceptibility of the material: at temperatures below 540 K, the magnetic susceptibility is low (due to electron spin pairing), while at high temperatures, a phase transition takes place, where the Ru–Ru bond lengths fluctuate and the dimers are no longer ordered over the structure, resulting in a greater unpaired electron spin density and a higher magnetic susceptibility.54

Figure 4.

Variable-temperature 17O NMR spectroscopy of Li2RuO3. (a) Structure of Li2RuO3 (left) with honeycomb ordering in the Li1/3Ru2/3 layers and ordered arrangement of Ru–Ru dimers (right). (b) Local O environments relative to the Ru–Ru dimers. (c) Room-temperature isotropic 17O NMR resonances for 17O-enriched Li2RuO3 at 11.7 T under 60 kHz MAS. (d) Variable-temperature 17O NMR Hahn-echo VOCS spectra acquired under 16.4 T and 14 kHz MAS. Adapted with permission from ref (41). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

The room-temperature 17O NMR Hahn-echo VOCS of Li2RuO3 comprised four distinct isotropic resonances whose shifts were rationalized based on shifts calculated using DFT and bond pathway analysis and by considering the local orbital interactions between the Ru–Ru dimers and the surrounding ligand field of O2– anions. The four resonances correspond to O2– which is on the inside edge of an Ru–Ru dimer [O1 in Figure 4b]; O2– on the outside edge of an Ru–Ru dimer (O2); O2– between a non-dimerized pair of Ru4+ cations (O3); and O2– which is axial relative to an Ru–Ru dimer [O4; Figure 4b,c].

The phase transition was then examined by using variable-temperature 7Li and 17O NMR (see ref (42) for the 7Li NMR spectra). On increasing temperature, the authors observed an increase in the shift of the 17O isotropic resonances [Figure 4d]. This is unusual, as one typically expects a decrease in isotropic shift, as, in most materials, the time-averaged electron spin decreases and hence the spin density transferred to nearby nuclei decreases with increasing temperature. In Li2RuO3, the low-lying paramagnetic states (corresponding to the non-dimerized structure) become accessible at higher temperatures, meaning that the time-averaged spin moment—and therefore the shift—increases.

At temperatures between room temperature and the high-temperature phase transition, two distinct 17O resonances were observed and assigned to the two crystallographic O sites in the high-temperature structure, 8j (2320 ppm) and 4i (2140 ppm), based on a qualitative comparison of the expected spin densities. The 8j site sits closer to the Ru cations, while the 4i sites sit farther away; this is analogous to the relative shifts of the 8j and 4i sites in (ordered) Li2MnO3. The other two resonances seen at room temperature were no longer present, which was ascribed to broadening and greater overlap of the resonances and sidebands, due to a slower MAS speed, as well as faster relaxation times induced by a greater magnetic susceptibility at higher temperatures and hence a stronger hyperfine interaction.

Above the phase transition, the two resonances broadened further and were again assigned to the two crystallographic environments (8j and 4i) in non-dimerized Li2RuO3. The authors noted, however, that the non-dimerized model was likely an approximation to a dynamic structure, in which short Ru–Ru distances persist but fluctuate rapidly on the NMR time scale. This rapid fluctuation contributed to the broadening of the resonances and led to a dynamically averaged hyperfine interaction.

This study highlighted how 17O NMR may be used as a tool for probing structural phase transformations in layered cathode materials—in terms of both the changes to local environments and the dynamics of these changes.

8. 17O NMR as a Tool for Ex Situ Characterization

We now turn to examining the changes in 17O NMR spectra on electrochemical cycling. Since NMR is a non-destructive technique, using only low-energy radiofrequency radiation, it is ideally suited to studying metastable compounds such as cycled cathode materials.

8.1. Li[Ni0.85Co0.10Al0.05]O2

LixNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2 (NCA) is a commercial battery cathode used in many EVs, and doping of Co and Al into the parent material, LiNiO2, significantly improves its electrochemical performance. To understand the local structural evolution of NCA during cycling, we obtained ex situ17O, 27Al, and 59Co NMR spectra. Here, we focus on the 17O NMR results and only briefly discuss the 27Al and 59Co NMR data (see SI for a longer discussion, section S5 and Figures S10–S15).

Pristine NCA contains paramagnetic Ni3+ and diamagnetic Co3+ and Al3+ ions, but with no long-range order of these cations in the TMO2 layers. Ni3+ is Jahn–Teller (JT) distorted—with very different calculated Fermi contact shifts for the shortened and lengthened Ni–O bonds [Table 1]. There is no overall ordering of the JT axes of Ni3+, and it has been argued that this is because the JT distortion is dynamic.

The 17O NMR spectrum of pristine NCA is severely broadened (width >30 000 ppm) with a high center-of-mass shift (ca. 13 000 ppm), likely due to a strong hyperfine interaction between the O nuclei and JT-distorted Ni3+ centers [Figure 5a].29 A sharp feature around 0 ppm is also seen, due to diamagnetic O2– either from surface impurities (e.g., Li2CO3, LiOH) or from O2– surrounded by diamagnetic (Al3+ and Co3+) centers in the transition metal layer. This diamagnetic feature is also consistent with a γ-LiAlO2 impurity phase seen in the 27Al NMR (Figure S10).

Figure 5.

17O, 7Li, 27Al, and 59Co NMR spectroscopy of 17O-enriched Li[Ni0.80Co0.15Al0.05]O2 (NCA). (a) 17O NMR VOCS data obtained for pristine NCA at 11.7 T under 60 kHz MAS and at “room temperature” (i.e., the ambient temperature of the rotor due to frictional heating, typically 320 K at 60 kHz). (b) Different paramagnetic local O environments and bond pathway contributions in pristine NCA. (c) Room-temperature spectra obtained for electrochemically charged (i.e., delithiated) NCA, also at 11.7 T under 60 kHz, with composition Li0.18[Ni0.8Co0.15Al0.05]O2 calculated based on the current passed.

Bond pathway analysis was used to assign the broad resonance, assuming a random TM distribution model, where any TM site can be occupied by Ni3+, Co3+, or Al3+, with occupation probabilities given by the NCA stoichiometry. We define three paramagnetic environments, categorized according to the number of nearest-neighbor Al3+ or Co3+ (dopant) centers—a 0-dopant site, where O is bound to three Ni3+ nearest neighbors; 1-dopant, where O has two Ni3+ and one Al3+ or Co3+ nearest neighbor; and 2-dopant, with one Ni3+ and two diamagnetic neighbors, Al3+ and/or Co3+—with relative concentrations of 51%, 38%, and 10%, respectively. The remaining sites (ca. 1%) are diamagnetic, with no Ni3+ neighbors. Additional complexity arises as a single Ni3+ neighbor can be coordinated to O via a JT-lengthened bond (whose bond pathway contribution is δL, approximately 12 500 ppm) or a JT-shortened bond (bond pathway shift δS, approximately 2300 ppm). These bond pathway contributions were taken from previous hybrid DFT calculations of Al-doped LiNiO2.27

For the 0-defect site, there are four “sub-environments”, due to different configurations of long and short JT-distorted Ni–O bonds. O can be bound to Ni3+ via three δL paths; two δL paths and one δS path; one δL path and two δS paths; or three δS paths [Figure 5b]. Under a dynamic JT distortion model—known to model the 7Li NMR spectra—the shift of the 0-defect site will be the thermodynamic average of these sub-environments. We anticipate that the environment with one δL path and two δS paths (total shift of 17 100 ppm) will be the lowest in energy (all others will be more strained and therefore higher energy). As a result, the shift of O with three Ni3+ nearest neighbors in a dynamic JT network will be close to the 17 100 ppm. The 17O NMR results are, therefore, consistent with a dynamic JT distortion.

The 1-dopant site comprises three local environments for a static JT, with total shifts of 25 000 ppm (2δL), 14 800 ppm (δL + δS), and 4600 ppm (2δS). Previous publications suggested that the dopants may pin the JT distortion so that the NiO6 long axis points toward the smaller Al3+ dopant. If all Ni3+ JT ions are dynamic, then a broad resonance is seen whose center-of-mass is an average of the above shifts results. This shift is likely weighted toward the low-strain δL + δS and 2δS environments (analogous to the 0-defect sites; Figure 5b).

Finally, for the 2-dopant sites, the shifts due to Ni3+ are either 12 500 ppm (δL) or 2300 ppm [δS; Figure 5b]. In the case of dynamic JT averaging, we expect a shift of 5700 ppm (i.e., (δL + 2δS)/3).

Independent of the degree of dynamics for the JT, a wide range of resonances are generated, and therefore the breadth of the observed resonances for pristine NCA likely arises from the overlap of several resonances with very different shifts. We must also consider the rapid fluctuation of the electron spin moment due to the dynamic JT axes. If the rate of these fluctuations (i.e., 1/tJT, where tJT is the time scale of a single JT fluctuation) is close to the frequency difference between the signals from different JT orientations, then significant line broadening will occur.55 The overlap of several of these individual broad resonances and their sideband manifolds results in a severely broadened spectrum.

The loss of paramagnetic Ni3+ centers on charging NCA is evident from 17O NMR: a simultaneous decrease in intensity near the paramagnetic region (13 000 ppm, as seen in the pristine material) and increase in intensity near the diamagnetic region (near 0 ppm) is seen, resulting in a much lower center-of-mass shift, around 600 ppm [Figure 5c]. Despite possible oxidation of diamagnetic Co3+ to paramagnetic Co4+ (note that some Li remains in the structure at the end of charge), little effect is seen in the 17O (or 7Li and 27Al) NMR, likely due to the small bond pathway shifts for Co4+ (Co4+ has only one unpaired electron). Furthermore, Co4+ induces rapid relaxation, and any resonances arising from environments with pathways to Co4+ may be severely broadened, analogous to the disappearance of the 7Li NMR signal in LiCoO2 on charging.56 As low-spin Co4+ is a t2g5 ion, its degenerate ground state has residual orbital angular momentum, potentially introducing further broadening mechanisms (see SI).

The 17O NMR results for electrochemically charged NCA are therefore consistent with oxidation of Ni3+ to Ni4+; further evidence for this charge compensation scheme can be seen in the 59Co NMR spectra (SI, Figures S14 and S15). Intriguingly, NCA at the end of charge has been shown to exhibit a feature in the O K-edge resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) spectrum at a certain energy.18 Some claim this as characteristic of highly covalent TM–O bonds and the removal of electron density from both the TM and O ions, while formally oxidizing the TM ion;18 others view this feature—albeit in different materials—as a signature for anion redox processes.57−60 No clear evidence for O oxidation is seen via the 27Al or 59Co NMR spectroscopy, and the 17O NMR spectra of NCA do not appear to contain any signals that can be assigned to either paramagnetic O species or any (O2)n− dimers, though the question remains: If paramagnetic O species exist, either holes or dimers, would they be observed? We discuss this further in the next section and provide a more detailed discussion of the results and charge compensation mechanisms in NCA in the SI (section S5). What is clear, however, is that acquisition of 17O from Ni3+-containing disordered samples is extremely challenging, as is the quantification of the 17O spectra with the accuracy required to rule out minor species. Thus, care must be taken in using 17O NMR to make definitive statements in the absence of other complementary characterization tools when disorder and paramagnetic Ni ions are present.

8.2. LiCoO2

Lithium cobalt oxide, LiCoO2 (LCO), has dominated the market as a cathode for LIBs in portable electronics for years.61 Pristine LCO adopts a layered O3 structure [Figure 6a], and its structural evolution during cycling is well-characterized [Figure 6b].62−64 The pristine phase can be partially delithiated before transforming via a two-phase reaction with a large immiscibility gap to a metallic phase O3met. O3met can be further delithated eventually forming another metallic phase, O′3met (with composition close to Li0.5CoO2), with an ordered array of Li+ ions and vacancies. This ordered phase has monoclinic symmetry and only persists over only a very small composition range. The symmetry of the O′3met phase, when further delithiated, returns to hexagonal (as the Li-ordering is lost) and eventually transforms into the H1-3 phase; further delithiation results in a two-phase reaction between H1-3 and the O1 phase, which persists to the end of charge [Figure 6a,b].

Figure 6.

Ex situ17O NMR results for LixCoO2 (1.00 < x < 0.07) during the first charge. (a) Structures of the O3, H1-3, and O1 phases of LixCoO2. (b) Corresponding voltage profile and locations of ex situ sample points. (c) 17O NMR spectra collected at 14.1 T under 24 kHz MAS. Adapted with permission from ref (38). Copyright 2019 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Commercially, LCO is generally only charged up to the O′3met structure, corresponding to 0.5 equiv of Li+ removed, as the (high-voltage) phase transformations are destructive, resulting in degradation of LCO and the electrolyte.65,66 We note that materials that can withstand cycling to 4.3 V vs Li have more recently been developed.67,68

To understand these destructive phase transformations, Geng et al. studied LCO using ex situ17O NMR for the first time, alongside 7Li and 59Co NMR.38 They prepared samples using 17O-enriched H2O—highlighting that this synthetic route may be successfully employed for layered cathode materials—and carried out post-mortem analysis on a series of cells cycled to different states of charge [Figure 6]. Single-pulse experiments were used, as the authors observed that the Hahn echo resulted in a loss of signal intensity during acquisition, due to rapid transverse relaxation times, T2. Additional experiments were carried out at a different receiver offset frequency. Note that a resonance with negative intensity appears at 378 ppm, corresponding to ZrO2, for reasons discussed in the SI (section S4).

The pristine LCO spectrum comprised a single, sharp resonance at −636 ppm from O2– centers bound to diamagnetic Co3+; this resonance is sharper than in paramagnetic LIB cathodes,37,39−41 as there is no hyperfine interaction between O and the nearby diamagnetic Co3+. On delithiating LCO up to point C5 (i.e., the O′3met phase up to Li0.5CoO2), the resonance at −636 ppm broadened and decreased in intensity; this was ascribed to a faster relaxation rate of 17O due to the formation of paramagnetic Co4+ centers. The loss of intensity of this resonance is, however, unsurprising, as the delithiation reaction occurs via a two-phase reaction to form a second distinct phase, O3met.

By correlating the 17O results with changes in the 7Li and 59Co NMR spectra, as well as the electrochemical profile and expected phases, the authors concluded that the 17O signal from the metallic phase O3met could not be observed. They assigned the resonance at 900 ppm to O2– in the Li+/vacancy ordered O′3met phase and the 1250 ppm resonance to O2– in the H1-3 phase.

One difficulty in interpreting these results is the lag between the appearance and disappearance of the different 17O resonances and the state of charge (as measured electrochemically), which the authors ascribed to their 17O labeling procedure: the characteristic 7Li signals were observed for each phase/stage, albeit at a different (nominal) Li+ content than expected. The authors ascribed the difficulty in observing the 17O resonance from the O3met phase to t2g electron delocalization (no signal was observed via 59Co NMR, either). They argued that this was evidence for high spin density near these nuclei, the large hyperfine interactions causing rapid relaxation of the NMR nuclei. Despite this, the 7Li signals are still observable, the observed shifts being ascribed to a transferred hyperfine interaction to Li nuclei via O2–. This phase is, however, generally considered to be metallic—as per conductivity measurements69—with the Li shift controlled by the Knight shift. However, the 17O results suggest that a simple metallic picture may not be appropriate and that some “intermediate” spin character may be needed to describe the Co ions; a more detailed variable-temperature NMR study is required to understand the nature of defects in pristine and cycled LCO, to reconcile the 17O and 7Li NMR shift mechanism, and to establish the role that hyperfine (with localized electron spin density) vs Knight shifts play in the observed spectra.

In addition to monitoring the different environments generated during charge, the authors extracted information about the quadrupolar interaction of each O environment. Good fits to the observed spectrum were obtained with a quadrupolar model, where the CQ was observed to increase from 1.47 MHz in pristine LCO to 7.22 and 7.98 MHz at higher states of charge. This large increase was ascribed to increasing covalency of the Co–O bond,52 due to the lowering in energy and contraction of the Co 3d orbitals (resulting in improved spatial and energetic overlap with the O 2p orbitals). Further studies to investigate the field dependences of the quadrupolar broadening would be useful to explore this change in CQ, especially since the changes in the degree of local ionicity and covalency of O have important ramifications for the charge compensation mechanism in layered LIB cathodes.70

9. High-Capacity Cathodes and 17O NMR: Oxidized Oxygen Species

We now examine the use of 17O NMR spectroscopy to study materials that nominally operate via anion redox processes. Oxidation of O is not necessarily surprising, given that oxidation of sulfur-based cathodes is well-known71−74 and that O oxidation readily occurs in biological settings.75 However, the nature of oxidized O (i.e., how these species are stabilized) remains under fierce debate and appears to be material-dependent. Broadly, the nature of oxidized oxygen may be classified in one of two groups: (1) superoxo/peroxo-like species and/or trapped O2 units;39,70,76−80 (2) rehybridization, delocalization, and changes to ionicity and covalency of the TM–O bonds and Li–O–Li units.81−84 Both schemes indicate that O participates in redox couples of layered cathode materials, with the extent of its involvement depending on the degree of local ionicity or covalency of O. An explanation of the most common mechanisms (formation of peroxo-like (O2)n− species;78−80 molecular oxygen trapping;39,77,85 localization of holes onto O;84,86,87TM migration;88−90 and π redox81) is beyond the scope of this Perspective, but a brief summary may be found in the SI, section S3 and Figures S4–S8.91

The most common method used to understand charge compensation mechanisms in O redox cathodes is O K-edge XAS.39,85,92−95 In particular, advanced XAS techniques such as RIXS and hard X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (HAXPES) are becoming increasingly common for examining the highest occupied and lowest unoccupied electronic states around O.92,94 While XAS can provide an element-specific local handle on the oxidation state and electronic and chemical structures of a material, the high-energy X-rays used in these techniques can damage the sample.93 Some studies have also chosen to incorporate XRD,88,89,96ab initio electronic structure calculations,81,82,97 electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy,37,98 and 6Li and 7Li NMR.37,39,85 Thus far, however, only two have used 17O NMR spectroscopy.37,39 We now examine why the application of 17O in these cases has been so challenging and discuss what information can be obtained.

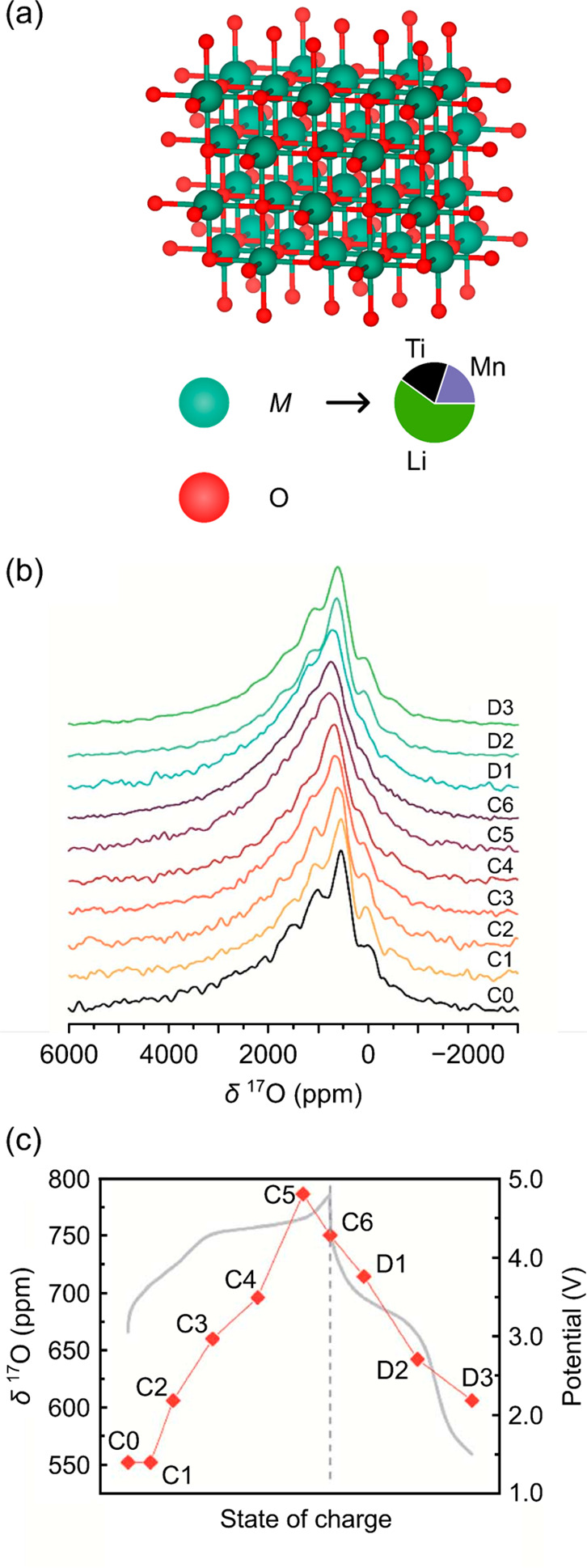

9.1. Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 (LTMO)

The first study to examine an O-redox-active cathode using 17O NMR was carried out by Geng et al. on Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2 (henceforth LTMO), a disordered rocksalt.37 Disordered rocksalts are a class of cathode materials which are distinct from (but related to) layered cathodes. They comprise two interpenetrating face-centered-cubic lattices of octahedrally coordinated ions: one of O2– anions and the other with a disordered (or partially ordered99) array of cations [Li+ and TM; Figure 7a]. Some disordered rocksalts may be made lithium-rich, where the Li:TM ratio exceeds 1 and Li+ cations replace TM centers; here, it is hypothesized that the highly ionic Li–O bonds raise the energy of the O non-bonding lone pairs, making these electrons available for reversible redox reactions.7,8,100−103

Figure 7.

17O NMR spectroscopy of the 17O-enriched disordered rocksalt Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2. (a) Structure of Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2, with a “random” distribution of the metal cations (Li+, Mn3+, and Ti4+). (b) Ex situ spectra recorded at 18.8 T under 60 kHz MAS, with the states of charge on the voltage curve in (c). Adapted with permission from ref (37). Copyright 2020 Royal Society of Chemistry.

To examine the charge compensation scheme, Geng et al. sought to identify the local structural changes through 17O NMR and, as discussed in their paper, 7Li NMR and EPR.37 The 17O NMR spectra for LTMO were acquired using a solid echo pulse sequence; the difference between this and the Hahn-echo and single-pulse experiments used in the earlier studies is detailed in the SI (section S4, p S-13).

Pristine LTMO has a 17O NMR spectrum which is severely broadened, with sidebands that overlap significantly with the most dominant and most intense isotropic resonance at approximately 550 ppm. The 550 ppm peak was assigned to O2– bound to Mn3+ centers [Figure 7b] and was confirmed as the isotropic resonance by acquiring spectra at different MAS speeds and field strengths. Given the shifts seen in the related layered materials where the paramagnetic ions have been found to cause large hyperfine shifts, it seems unlikely that this assignment is correct. Since the spectra in this work are not VOCS, we anticipate that only a small portion of the spectrum was recorded, and that additional isotropic resonances may lie at higher frequencies—even in the spectrum presented, a broader signal (which may not have been fully excited under the acquisition conditions) sitting underneath, but at higher frequencies than the 550 ppm resonance, is likely present.

The severe broadening of the observed spectrum was assigned to a broad distribution of local environments, a consequence of the disordered nature of the material, as well as the presence of strongly paramagnetic Mn3+ cations, resulting in rapid nuclear relaxation rates.

On charging LTMO, the 17O isotropic shift moved to slightly higher frequencies (ca. 780 ppm). The shift decreased on discharge but did not return to the same shift as the pristine material, reflecting the hysteretic behavior seen over the first charge–discharge cycle [Figure 7b,c]. It was suggested that the small increase in shift is due to the similar Fermi contact shifts induced by Mn4+ and (O2)n− (peroxo-like) species. The authors also noted a broader sideband manifold in the 17O NMR spectrum on charging and ascribed it to a stronger quadrupolar interaction (i.e., a larger CQ and therefore a more covalent TM–O bond) and/or a broader distribution in local environments.

Given that O bound to Ti typically resonates near 500 ppm31,104 and that the probability of not having a paramagnetic Mn in the first coordination sphere, but instead having a configuration OTixLi6–x (where 0 < x ≤ 6), constitutes a significant fraction of the oxygen sites (26%), we reassign the 550 ppm resonance to O bound to Ti4+ rather than Mn3+ centers. The broad shoulder to higher frequencies is then due to configurations with Mn3+ ions in the first coordination shell. At C3, all Mn3+ should have been oxidized to Mn4+, based on the typical bond pathways expected for Mn4+ bound to O—i.e., 900–1100 ppm for a nearest neighbor and 200 ppm for a next-nearest neighbor, based on the bond pathways in Li2MnO3—and given that no new resonances are observed at this state of charge, we expect that any environments in which O is surrounded by Mn are at higher frequencies and likely buried in the broad shoulder.

The typical 17O shift range of diamagnetic peroxide species is 200–800 ppm,43 suggesting that the assignment of some of the observed signal as (O2)n− is at least plausible. However, it is well-known that peroxide species have large CQ values105 (up to 20 MHz for Li2O2), suggesting that this assignment would need to be verified via calculations of the CQ and shift parameters. It appears likely that distortions in the O sublattice are seen as the Li+ ions are removed, resulting in broadening of the O signals, and it is more likely that these species are, in fact, lattice oxygen.

More importantly, if there are unpaired electrons on O (i.e., if n in (O2)n− deviates from 2), it seems highly unlikely that the 17O signals could be seen using NMR: the rapid relaxation induced by the extremely strong hyperfine interactions would likely cause signal decay within the dead time, resulting in severely broadened features and/or a significant loss of signal intensity.

9.2. Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 (LR-NMC)

The second (published) study to have explored the charge compensation mechanism of high-capacity cathode materials using 17O NMR (among other techniques) was from House et al., who studied a lithium-rich nickel–manganese–cobaltate (NMC) material.39 As in lithium-rich rocksalts, Li+ ions in lithium-rich layered cathodes substitute some of the TM cations in the TMO2 layers [Figure 8a]. In this work, House et al. studied Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 (henceforth LR-NMC) to understand the charge compensation scheme during the first charge–discharge cycle [Figure 8b].

Figure 8.

17O NMR spectroscopy of the 17O-enriched lithium-rich cathode Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2. (a) Structure of Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2, with a honeycomb arrangement of the Li+ and TM cations. (b) Ex situ sampling points on the voltage curve, with the corresponding spectra shown in (c), recorded at 9.45 T under 34 kHz MAS. Adapted with permission from ref (39). Copyright 2020 Nature-Springer group.

On the basis of O K-edge RIXS data obtained at the end of charge, the authors proposed that charge compensation in LR-NMC proceeded via the oxidation of the lattice oxygen, which is subsequently stabilized by pairing, TM migration, and the formation of trapped O2. To complement their RIXS data, they acquired ex situ17O NMR spectra using a short-delay pre-saturation echo pulse sequence (as illustrated and discussed in the SI, Figure S9). Briefly, the pre-saturation sequence enables only species with short longitudinal relaxation times, T1, to be observed. In theory, if O becomes strongly paramagnetic and relaxes quickly, it would be more clearly separated from the diamagnetic species than if longer delays were used.

The 17O NMR spectrum of pristine LR-NMC showed a severely broadened signal, which, while not explicitly assigned or fitted by the authors, likely arises from overlapping resonances which correspond to O2– ligands bound to varying numbers of Mn, Ni, and Co cations;39 each of these resonances will likely have a rapid transverse relaxation time (T2), due to the strongly paramagnetic nature of the TM cations,45 resulting in a broad resonance [Figure 8c], consistent with the 17O spectrum obtained for NCA [Figure 7].

On charging, a (comparatively) sharp resonance develops at approximately 2800 ppm, which becomes more intense and moves to approximately 3200 ppm at the end of the first charge [Figure 8c]. This resonance was assigned to trapped molecular O2, based on a prior study that reported the 17O NMR spectrum of condensed (liquid) 17O2 at 77 K. While the experimental magnet strengths and temperatures differ between the two studies, a Curie–Weiss scaling may be used to translate between the shifts.46 Assuming a Weiss constant of −71.3 K (from ref (106)), and converting from the reported shift of 8220 G for liquid O2, we obtain a shift of approximately 10 980 ppm for O2 at 310 K (the temperature expected at this MAS frequency; see SI, section S7, for details on conversion calculations), which is significantly different from the observed resonance reported by House et al.39

The shift of the observed resonance is, however, comparable to those seen for 17O2 environments in isolated haem complexes (whose shifts lie around 1600–2000 ppm).107 These complexes contain strongly coupled TM–O2 interactions, such that the Fe–O2 complex is diamagnetic, with the 17O2 changing very little between 298 and 77 K. Thus, if this is indeed “O2”, then it cannot be free triplet (S = 1) oxygen, and it must interact strongly with the metal sublattice. Such O2 species would also likely have large CQ values (comparable to peroxides, up to 5 MHz107); this quantity can be readily obtained via DFT.

Based on the shift and rapidly relaxing nature of the resonance seen by House et al.,39 it is also possible that this resonance corresponds to O environments bound to strongly paramagnetic Mn4+ and/or Co4+ cations (note that Ni4+ is expected to be diamagnetic). Furthermore, as previously shown for the Li2MnO3 system, O sites connected to two Mn4+ are expected to have shifts around 2000 pm, suggesting that these new features are simply O bound to Mn with longer 17O T1,2 relaxation times (giving rise to sharper resonances), and which become visible due to the loss of paramagnetic Ni2+ and Ni3+ centers.

The study by House et al. highlights the importance of using several techniques—both theoretical and experimental—to probe the changes to electronic and chemical structure so as to verify the assignments.

9.3. Li2MnO3

The most recent study of the O redox mechanism using 17O NMR examined Li2MnO3 both ex situ and in situ.108 On cycling, the reversible capacity extracted from this material is, in principle, charge compensated by O redox only, as Mn is already in the +4 oxidation state. In this study, Li et al. synthesized 17O-enriched Li2MnO3as per the method used by Seymour et al.40 and carried out pjMATPASS experiments on ex situ cycled samples. Importantly, the authors showed that in situ (static) 17O NMR was possible through use of the quadrupolar Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (qCPMG) to increase the sensitivity and temporal resolution of spectra.109,110 A gradual loss in the intensity of all O peaks on charging was seen, where the losses in intensity were greatest for 17O environments from the stacking-faulted (P3112) domains. This was ascribed to formation of paramagnetic O species, predominantly stabilized via Mn–O π redox (see SI, sections S3 and S9 and Figure S17). Additional signals were observed, which we suggest arise from degradation products, most likely facilitated by proton insertion and densification at the surface of Li2MnO3 particles.111−113 This work highlights the utility of 17O in analyzing local structures during operation of a battery—i.e., without the structural relaxation that may occur in ex situ samples after cycling.

10. Outlook and Conclusions

17O NMR spectroscopy is an invaluable technique for determining the local structures of LIB—and indeed other—cathode materials. It is capable of reporting the changes to chemical structure, phase transformations, and electronic structure during charge and discharge.40,41

In the pristine material, the O starts as an oxide ion and is generally bound to at least one highly paramagnetic TM center, resulting in a strong hyperfine interaction, large shifts, and rapid nuclear relaxation. How well-defined or broadened a resonance is depends primarily on the strength of the hyperfine interaction, the 17O nuclear relaxation times, and the distribution of local environments. The quadrupolar interaction also contributes to the observed breadth, but generally to a much smaller extent.

Spectra with well-defined resonances are anticipated for ordered compounds (e.g., Li2RuO3), systems where the O species are not bound to a dynamic Jahn–Teller distorted paramagnetic center (i.e., not bound to Mn3+ or Ni3+), where O has distinct chemical environments, and/or where little or no spin–orbit coupling is present. Where resolved signals are seen, e.g., in Mn4+-containing compounds such as Li2MnO3, disorder can be probed—for example, stacking faults which generate discrete local environments with distinct (and calculable) hyperfine shifts. For systems containing Ni2+/3+, Mn3+, and Co4+, significant broadening of the resonances results, likely from JT distortions and/or non-zero orbital angular momentum, L, particularly when fluctuations (such as the dynamic JT effect) are present on the time scale of the hyperfine interaction. Magnetic interactions between paramagnetic ions, or spin pairing for paramagnetic systems that undergo metal–insulator transitions, will also result in broadening as the magnetic or metallic phase, respectively, is approached. Additional work is required to understand these broadening mechanisms, perhaps using EPR and/or magnetic susceptibility studies.

Hybrid DFT calculations of the expected shifts not only assist the assignment and interpretation of a spectrum but also aid in the initial search for a resonance. However, care must be taken when making assignments: one must ask whether the observed resonance(s) are from diamagnetic surface species (and thus easier to see, e.g., Li2CO3, Li2O) or from the bulk, and indeed if the full spectrum has been excited (i.e., whether VOCS is necessary). Are the spectra quantitative, and are all the signals from the whole sample being seen, or are some signals lost via some of the mechanisms discussed above?

Further information may be gleaned by extracting the quadrupolar parameters, since these report the degree of ionicity and covalency. To properly assess and extract these quadrupolar parameters, further experiments are often required, be it measurements at different field strengths, nutation profiles (by acquiring spectra with different pulse lengths), or the use of quadrupolar-filtering pulse sequences.29 Variable-temperature experiments are also important to help tease apart the various interactions—be they diamagnetic, Fermi-contact, or Knight shift—and to explore the nature of magnetic interactions in these systems.

Having established the nature of O environments in the pristine material, the consequences of cycling can be explored using similar approaches. The width of the observed resonances and the short nuclear relaxation times make it extremely challenging to assign spectra to specific O environments, be they O2– anions or more oxidized oxygen species.

Moving forward, 17O NMR should be a useful tool for exploring the inherently challenging O redox chemistry, as it provides a non-destructive method of examining the local chemical environment around O. From the studies presented in this Perspective, it is clear that further work is required to fully understand how paramagnetic O centers (either as holes on O, delocalized spin states, or (O2)n−-like species) manifest in the 17O NMR spectrum of cathodes at the end of charge.

As new materials are discovered, it may be possible to find systems containing fewer paramagnetic ions and local environments, to simplify the analysis. Dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP) using endogenous radicals may enhance the 17O signals and select for nearby environments,114 and, again, with a judicious choice of system with only dilute paramagnetic ions, low-concentration O defects may become visible. Care must also be taken that electrolyte reactions do not complicate the analysis, particularly at high states of charge where proton insertion is common.

It is also advisable to obtain additional data, for example, magnetometry to understand the number of and interactions between unpaired electrons and EPR to probe the local environment of these unpaired electrons. When combined, a truly holistic picture of both the charge compensation mechanism and the structural evolution of a cathode during cycling may be obtained, and controversial questions regarding the nature of oxygen’s involvement in the electrochemistry of this class of materials may be answered.

Acknowledgments

E.N.B. acknowledges funding from the Engineering Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) via the National Productivity Interest Fund (NPIF) 2018. C.P.G., I.D.S., and P.J.R. acknowledge the NorthEast Center for Chemical Energy Storage (NECCES), an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Award DE-SC0012583. E.N.B. would also like to dedicate this work to K.R. Bassey.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c02927.

Discussion of the O redox charge compensation schemes, results, and subsequent discussion of NMR data acquired for NCA (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ma J.; Li Y.; Grundish N. S.; Goodenough J. B.; Chen Y.; Guo L.; Peng Z.; Qi X.; Yang F.; Qie L.; Wang C.-A.; Huang B.; Huang Z.; Chen L.; Su D.; Wang G.; Peng X.; Chen Z.; Yang J.; He S.; Zhang X.; Yu H.; Fu C.; Jiang M.; Deng W.; Sun C.-F.; Pan Q.; Tang Y.; Li X.; Ji X.; Wan F.; Niu Z.; Lian F.; Wang C.; Wallace G. G.; Fan M.; Meng Q.; Xin S.; Guo Y.-G.; Wan L.-J. The 2021 Battery Technology Roadmap. J. Phys. Appl. Phys. 2021, 54 (18), 183001. 10.1088/1361-6463/abd353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tarascon J.-M.; Armand M. Issues and Challenges Facing Rechargeable Lithium Batteries. Nature 2001, 414 (6861), 359–367. 10.1038/35104644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blomgren G. E. The Development and Future of Lithium Ion Batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164 (1), A5019. 10.1149/2.0251701jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmuch R.; Wagner R.; Hörpel G.; Placke T.; Winter M. Performance and Cost of Materials for Lithium-Based Rechargeable Automotive Batteries. Nat. Energy 2018, 3 (4), 267–278. 10.1038/s41560-018-0107-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manthiram A. A Reflection on Lithium-Ion Battery Cathode Chemistry. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 1–9. 10.1038/s41467-020-15355-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radin M. D.; Hy S.; Sina M.; Fang C.; Liu H.; Vinckeviciute J.; Zhang M.; Whittingham M. S.; Meng Y. S.; Van Der Ven A. Narrowing the Gap between Theoretical and Practical Capacities in Li-Ion Layered Oxide Cathode Materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2017, 7, 1602888–1602888. 10.1002/aenm.201602888. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; MacNeil D. D.; Dahn J. R. Layered Li[NixCo1–2xMnx]O2 Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2001, 4 (12), A200. 10.1149/1.1413182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z.; MacNeil D. D.; Dahn J. R. Layered Cathode Materials Li [ Ni x Li (1/3 - 2x/3) Mn (2/3 - x/3) ] O 2 for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 2001, 4 (11), A191. 10.1149/1.1407994. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He P.; Yu H.; Li D.; Zhou H. Layered Lithium Transition Metal Oxide Cathodes towards High Energy Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22 (9), 3680–3695. 10.1039/c2jm14305d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manthiram A.; Song B.; Li W. A Perspective on Nickel-Rich Layered Oxide Cathodes for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2017, 6, 125–139. 10.1016/j.ensm.2016.10.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavi S.; Subba Rao G. V.; Chowdari B. V. R.; Li S. F. Y. Effect of Aluminium Doping on Cathodic Behaviour of LiNi0.7Co0.3O2. J. Power Sources 2001, 93 (1–2), 156–162. 10.1016/S0378-7753(00)00559-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weaving J. S.; Coowar F.; Teagle D. A.; Cullen J.; Dass V.; Bindin P.; Green R.; Macklin W. J. Development of High Energy Density Li-Ion Batteries Based on LiNi1-x-yCoxAlyO2. J. Power Sources 2001, 97–98, 733–735. 10.1016/S0378-7753(01)00700-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yabuuchi N.; Ohzuku T. Novel Lithium Insertion Material of LiCo1/3Ni1/3Mn1/3O2 for Advanced Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Power Sources 2003, 119–121, 171–174. 10.1016/S0378-7753(03)00173-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas C.; Fouassier C.; Hagenmuller P. Structural Classification and Properties of the Layered Oxides. Phys. BC 1980, 99 (1–4), 81–85. 10.1016/0378-4363(80)90214-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C.; Märker K.; Lee J.; Mahadevegowda A.; Reeves P. J.; Day S. J.; Groh M. F.; Emge S. P.; Ducati C.; Layla Mehdi B.; Tang C. C.; Grey C. P. Bulk Fatigue Induced by Surface Reconstruction in Layered Ni-Rich Cathodes for Li-Ion Batteries. Nat. Mater. 2021, 20, 84–92. 10.1038/s41563-020-0767-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Märker K.; Reeves P. J.; Xu C.; Griffith K. J.; Grey C. P. Evolution of Structure and Lithium Dynamics in LiNi 0.8 Mn 0.1 Co 0.1 O 2 (NMC811) Cathodes during Electrochemical Cycling. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31 (7), 2545–2554. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.9b00140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grenier A.; Reeves P. J.; Liu H.; Seymour I. D.; Märker K.; Wiaderek K. M.; Chupas P. J.; Grey C. P.; Chapman K. W. Intrinsic Kinetic Limitations in Substituted Lithium Layered Transition-Metal Oxide Electrodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (15), 7001–7011. 10.1021/jacs.9b13551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebens-Higgins Z. W.; Faenza N. V.; Radin M. D.; Liu H.; Sallis S.; Rana J.; Vinckeviciute J.; Reeves P. J.; Zuba M. J.; Badway F.; Pereira N.; Chapman K. W.; Lee T.-L.; Wu T.; Grey C. P.; Melot B. C.; Van Der Ven A.; Amatucci G. G.; Yang W.; Piper L. F. J. Revisiting the Charge Compensation Mechanisms in LiNi0.8Co0.2-yAlyO2 Systems. Mater. Horiz. 2019, 6 (10), 2112–2123. 10.1039/C9MH00765B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lebens-Higgins Z. W.; Halat D. M.; Faenza N. V.; Wahila M. J.; Mascheck M.; Wiell T.; Eriksson S. K.; Palmgren P.; Rodriguez J.; Badway F.; Pereira N.; Amatucci G. G.; Lee T.-L.; Grey C. P.; Piper L. F. J. Surface Chemistry Dependence on Aluminum Doping in Ni-Rich LiNi0.8Co0.2-yAlyO2 Cathodes. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9 (1), 17720. 10.1038/s41598-019-53932-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croy J. R.; Balasubramanian M.; Kim D.; Kang S.-H.; Thackeray M. M. Designing High-Capacity, Lithium-Ion Cathodes Using X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2011, 23 (24), 5415–5424. 10.1021/cm2026703. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ceder G.; Chiang Y.-M.; Sadoway D. R.; Aydinol M. K.; Jang Y.-I.; Huang B. Identification of Cathode Materials for Lithium Batteries Guided by First-Principles Calculations. Nature 1998, 392 (6677), 694–696. 10.1038/33647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meng Y. S.; Dompablo M. E. A. Recent Advances in First Principles Computational Research of Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46 (5), 1171–1180. 10.1021/ar2002396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour I. D.; Chakraborty S.; Middlemiss D. S.; Wales D. J.; Grey C. P. Mapping Structural Changes in Electrode Materials: Application of the Hybrid Eigenvector-Following Density Functional Theory (DFT) Method to Layered Li0.5MnO2. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27 (16), 5550–5561. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.5b01674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour I. D.; Wales D. J.; Grey C. P. Preventing Structural Rearrangements on Battery Cycling: A First-Principles Investigation of the Effect of Dopants on the Migration Barriers in Layered Li 0.5 MnO 2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120 (35), 19521–19530. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.6b05307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida T.; Hongo K.; Maezono R. First-Principles Study of Structural Transitions in LiNiO2 and High-Throughput Screening for Long Life Battery. J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123 (23), 14126–14131. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b12556. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier D.; Ménétrier M.; Grey C. P.; Delmas C.; Ceder G. Understanding the NMR Shifts in Paramagnetic Transition Metal Oxides Using Density Functional Theory Calculations. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67 (17), 174103. 10.1103/PhysRevB.67.174103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Trease N. M.; Seymour I. D.; Radin M. D.; Liu H.; Liu H.; Hy S.; Chernova N.; Parikh P.; Devaraj A.; Wiaderek K. M.; Chupas P. J.; Chapman K. W.; Whittingham M. S.; Meng Y. S.; Van Der Van A.; Grey C. P. Identifying the Distribution of Al 3+ in LiNi0.8Co0.15Al0.05O2. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28 (22), 8170–8180. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b02797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grey C. P.; Dupré N. NMR Studies of Cathode Materials for Lithium-Ion Rechargeable Batteries. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104 (10), 4493–4512. 10.1021/cr020734p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halat D. M.; Dunstan M. T.; Gaultois M. W.; Britto S.; Grey C. P. Study of Defect Chemistry in the System La2-XSrxNiO4+δ by 17O Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy and Ni K-Edge XANES. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30 (14), 4556–4570. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b00747. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hope M. A.; Halat D. M.; Lee J.; Grey C. P. A 17O Paramagnetic NMR Study of Sm2O3, Eu2O3, and Sm/Eu-Substituted CeO2. Solid State Nucl. Magn. Reson. 2019, 102, 21–30. 10.1016/j.ssnmr.2019.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashbrook S. E.; Smith M. E. Solid State 17O NMR—an Introduction to the Background Principles and Applications to Inorganic Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35 (8), 718–735. 10.1039/B514051J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong X.; Terskikh V. V.; Khade R. L.; Yang L.; Rorick A.; Zhang Y.; He P.; Huang Y.; Wu G. Solid-State 17O NMR Spectroscopy of Paramagnetic Coordination Compounds. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (16), 4753–4757. 10.1002/anie.201409888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verkhovskii S.; Trokiner A.; Gerashenko A.; Yakubovskii A.; Medvedeva N.; Litvinova Z.; Mikhalev K.; Buzlukov A. 17O NMR Evidence for Vanishing of Magnetic Polarons in the Paramagnetic Phase of Ceramic CaMnO3. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81 (14), 144415. 10.1103/PhysRevB.81.144415. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashbrook S. E.; Berry A. J.; Frost D. J.; Gregorovic A.; Pickard C. J.; Readman J. E.; Wimperis S. 17O and 29Si NMR Parameters of MgSiO3 Phases from High-Resolution Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy and First-Principles Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129 (43), 13213–13224. 10.1021/ja074428a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hope M. A.; Halat D. M.; Magusin P. C. M. M.; Paul S.; Peng L.; Grey C. P. Surface-Selective Direct 17 O DNP NMR of CeO 2 Nanoparticles. Chem. Commun. 2017, 53 (13), 2142–2145. 10.1039/C6CC10145C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L.; Liu Y.; Kim N.; Readman J. E.; Grey C. P. Detection of Brønsted Acid Sites in Zeolite HY with High-Field 17O-MAS-NMR Techniques. Nat. Mater. 2005, 4 (3), 216–219. 10.1038/nmat1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng F.; Hu B.; Li C.; Zhao C.; Lafon O.; Trébosc J.; Amoureux J. P.; Shen M.; Hu B. Anionic Redox Reactions and Structural Degradation in a Cation-Disordered Rock-Salt Li1.2Ti0.4Mn0.4O2cathode Material Revealed by Solid-State NMR and EPR. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8 (32), 16515–16526. 10.1039/D0TA03358H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Geng F.; Shen M.; Hu B.; Liu Y.; Zeng L.; Hu B. Monitoring the Evolution of Local Oxygen Environments during LiCoO2 Charging: Via Ex Situ 17O NMR. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (52), 7550–7553. 10.1039/C9CC03304A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House R. A.; Rees G. J.; Pérez-Osorio M. A.; Marie J.-J.; Boivin E.; Robertson A. W.; Nag A.; Garcia-Fernandez M.; Zhou K.-J.; Bruce P. G. First-Cycle Voltage Hysteresis in Li-Rich 3d Cathodes Associated with Molecular O2 Trapped in the Bulk. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 777–785. 10.1038/s41560-020-00697-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour I. D.; Middlemiss D. S.; Halat D. M.; Trease N. M.; Pell A. J.; Grey C. P. Characterizing Oxygen Local Environments in Paramagnetic Battery Materials via 17O NMR and DFT Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (30), 9405–9408. 10.1021/jacs.6b05747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves P. J.; Seymour I. D.; Griffith K. J.; Grey C. P. Characterizing the Structure and Phase Transition of Li 2 RuO 3 Using Variable-Temperature 17 O and 7 Li NMR Spectroscopy. Chem. Mater. 2019, 31 (8), 2814–2821. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.8b05178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin J. M.; Clark L.; Seymour V. R.; Aldous D. W.; Dawson D. M.; Iuga D.; Morris R. E.; Ashbrook S. E. Ionothermal 17 O Enrichment of Oxides Using Microlitre Quantities of Labelled Water. Chem. Sci. 2012, 3 (7), 2293–2300. 10.1039/c2sc20155k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerothanassis I. P. Oxygen-17 NMR Spectroscopy: Basic Principles and Applications (Part I). Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2010, 56 (2), 95–197. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerothanassis I. P. Oxygen-17 NMR Spectroscopy: Basic Principles and Applications (Part II). Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2010, 57 (1), 1–110. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pell A. J.; Pintacuda G.; Grey C. P. Paramagnetic NMR in Solution and the Solid State. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2019, 111 (May), 1–271. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Middlemiss D. S.; Chernova N. A.; Zhu B. Y. X.; Masquelier C.; Grey C. P. Linking Local Environments and Hyperfine Shifts: A Combined Experimental and Theoretical 31 P and 7 Li Solid-State NMR Study of Paramagnetic Fe(III) Phosphates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132 (47), 16825–16840. 10.1021/ja102678r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clément R. J.; Pell A. J.; Middlemiss D. S.; Strobridge F. C.; Miller J. K.; Whittingham M. S.; Emsley L.; Grey C. P.; Pintacuda G. Spin-Transfer Pathways in Paramagnetic Lithium Transition-Metal Phosphates from Combined Broadband Isotropic Solid-State MAS NMR Spectroscopy and DFT Calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (41), 17178–17185. 10.1021/ja306876u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodenough J. B. An Interpretation of the Magnetic Properties of the Perovskite-Type Mixed Crystals La(1-x)Sr(x)CoO(3-y). J. Phys. Chw Solids Pergamon Press 1958, 6, 287–297. 10.1016/0022-3697(58)90107-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori J. Theory of the Magnetic Properties of Ferrous and Cobaltous Oxides, I. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1957, 17 (2), 177–196. 10.1143/PTP.17.177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kanamori J. Theory of the Magnetic Properties of Ferrous and Cobaltous Oxides, II. Prog. Theor. Phys. 1957, 17 (2), 197–222. 10.1143/PTP.17.197. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pell A. J.; Clément R. J.; Grey C. P.; Emsley L.; Pintacuda G. Frequency-Stepped Acquisition in Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy under Magic Angle Spinning. J. Chem. Phys. 2013, 138 (11), 114201. 10.1063/1.4795001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schramm S.; Oldfield E. High-Resolution Oxygen-17 NMR of Solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106 (9), 2502–2506. 10.1021/ja00321a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bréger J.; Jiang M.; Dupré N.; Meng Y. S.; Shao-Horn Y.; Ceder G.; Grey C. P. High-Resolution X-Ray Diffraction, DIFFaX, NMR and First Principles Study of Disorder in the Li 2MnO 3-Li[Ni 1/2Mn 1/2]O 2 Solid Solution. J. Solid State Chem. 2005, 178 (9), 2575–2585. 10.1016/j.jssc.2005.05.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miura Y.; Sato M.; Yamakawa Y.; Habaguchi T.; O̅no Y. Structural Transition of Li 2 RuO 3 Induced by Molecular-Orbit Formation. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 78, 094706. 10.1143/JPSJ.78.094706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt M. H.Motional Lineshapes and Two-Site Exchange. Spin Dynamics; John Wiley & Sons Ltd: Southampton, 2007; pp 516–527. [Google Scholar]

- Ménétrier M.; Saadoune I.; Levasseur S.; Delmas C. The Insulator-Metal Transition upon Lithium Deintercalation from LiCoO2: Electronic Properties and 7Li NMR Study. J. Mater. Chem. 1999, 9 (5), 1135–1140. 10.1039/a900016j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo Z.; Liu Y.; Guo J.; Chuang Y.; Pan F.; Yang W. Full Energy Range Resonant Inelastic X-Ray Scattering of O 2 and CO 2 : Direct Comparison with Oxygen Redox State in Batteries. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2020, 11 (7), 2618–2623. 10.1021/acs.jpclett.0c00423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N.; Sallis S.; Papp J. K.; Wei J.; McCloskey B. D.; Yang W.; Tong W. Unraveling the Cationic and Anionic Redox Reactions in a Conventional Layered Oxide Cathode. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4 (12), 2836–2842. 10.1021/acsenergylett.9b02147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Li Q.; Sallis S.; Zhuo Z.; Gent W. E.; Chueh W. C.; Yan S.; Chuang Y.-d.; Yang W. Fingerprint Oxygen Redox Reactions in Batteries through High-Efficiency Mapping of Resonant Inelastic X-Ray Scattering. Condens. Matter 2019, 4 (1), 5. 10.3390/condmat4010005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rong X.; Liu J.; Hu E.; Liu Y.; Wang Y.; Wu J.; Yu X.; Page K.; Hu Y.-S.; Yang W.; Li H.; Yang X.-Q.; Chen L.; Huang X. Structure-Induced Reversible Anionic Redox Activity in Na Layered Oxide Cathode. Joule 2018, 2 (1), 125–140. 10.1016/j.joule.2017.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Whittingham M. S. Lithium Batteries and Cathode Materials. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104 (10), 4271–4301. 10.1021/cr020731c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amatucci G. G.; Tarascon J. M.; Klein L. C. CoO2, The End Member of the Li x CoO2 Solid Solution. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1996, 143 (3), 1114. 10.1149/1.1836594. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Ven A.; Aydinol M. K.; Ceder G.; Kresse G.; Hafner J. First-Principles Investigation of Phase Stability in LixCoO2. Phys. Rev. B 1998, 58 (6), 2975. 10.1103/PhysRevB.58.2975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z.; Lu Z.; Dahn J. R. Staging Phase Transitions in Li x CoO 2. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2002, 149 (12), A1604. 10.1149/1.1519850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rinkel B. L. D.; Hall D. S.; Temprano I.; Grey C. P. Electrolyte Oxidation Pathways in Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (35), 15058–15074. 10.1021/jacs.0c06363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano A.; Shikano M.; Ueda A.; Sakaebe H.; Ogumi Z. LiCoO2 Degradation Behavior in the High-Voltage Phase Transition Region and Improved Reversibility with Surface Coating. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164 (1), A6116. 10.1149/2.0181701jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]