Abstract

The oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) located in photosystem II (PSII) of green plants is one of the best-known examples of a manganese-containing enzyme in nature, but it is also used in a range of other biological processes. OEC models incorporate two multi-dentate nitrogen-containing ligands coordinated to a bis-μ-oxo Mn(III,IV) core. Open-chain ligands were the initial scaffold used for biomimetic studies, but their macrocyclic counterparts have proven to be particularly appropriate due to their enhanced stability. Dimer and monomer complexes with such ligands have shown to be useful for a wide range of applications, which will be reviewed herein. The purpose of this review is to state with some clarity the different spectroscopic and structural characteristics of the Mn complexes formed with tetraaza macrocyclic ligands both in solution and solid-state that allow the reader to successfully identified the species involved when dealing with similar complexes of Mn.

Keywords: Dimers, Manganese, MnCAT, SOD, Tetraaza, macrocyclic ligands

Graphical Abstract

The reactivity of manganese metalloenzymes, Oxygen Evolving Complex and Catalase, have resulted in a small library of complexes derived from macrocyclic Mn(III) complexes and Mn(III)/Mn(IV) μ-oxo dimer complexes.

Manganese (III/IV) μ-Oxo Dimers and Manganese (III) Monomers with Tetraaza Macrocyclic Ligands and Historically Relevant Open-Chain Ligands

1. Introduction

Manganese can access a range of oxidation states:−3 up to +10 (being +2, +3, +4, and +7 the most common).[1] The resulting reactivity makes this transition metal useful in a variety of practical applications including metallurgy,[2] batteries,[3] and redox catalysis.[4] Likewise, manganese plays an essential role in a multitude of biological systems and can be found in numerous oxidation states and nuclearities within the active sites of metalloenzymes.[5] It is an ideal cofactor for a variety of metalloproteins with many diverse redox functions.[1b]

Examples of manganese-containing enzymes include superoxide dismutase (SOD), manganese catalase (MnCAT), and the oxygen-evolving complex (OEC) within photosystem II (PSII). SOD is a manganese-containing enzyme that catalyzes the disproportionation of the superoxide ion (O2− ) into either oxygen (O2) or hydrogen peroxide (H2O2).[6] The antioxidant capacity of Mn-SOD is an important defense against O2−, which is a by-product of oxygen metabolism of living cells exposed to oxygen. The active site of Mn-SOD is composed of a mononuclear manganese center with trigonal bipyramidal coordination geometry.[5a,7] Another manganese-containing enzyme, MnCAT, catalyzes the disproportionation of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) into water (H2O) and molecular oxygen (O2).[5a] The active site of MnCAT contains a dinuclear manganese center that is bridged by two oxygen atoms from water or hydroxide.[5a] Additionally, the dinuclear manganese center is also anchored by a bridging carboxylate from a glutamate residue.[5a] In another example, the OEC within PSII of green plants catalyzes the oxidation of water in the photosynthetic pathway. The OEC active site is composed of a tetranuclear manganese cluster, with several of the manganese atoms connected through μ-oxo bridges.[5a] As a result of the importance of manganese in biology and to understand the reactivity of these systems, a broad range of biomimetic complexes have been produced.

Manganese can form a plethora of coordination complexes with a variety of ligand sets.[8] Open-chain ligands were then the first scaffold of use, due to their simplicity and widespread application, but macrocyclic ligands, particularly N-rich systems derived from previous open-chain structures, provide a unique coordination environment to study the spectroscopy and reactivity of manganese complexes, due to the degree of customization that this systems provide in regard to rigidity, basicity and coordination environment.[9] Penta-aza macrocyclic ligands have been used to synthesize Mn(II) complexes that can serve as mimics for the active site of SOD. Likewise, other multidentate nitrogen-containing ligands have been used to synthesize Mn(III,IV) complexes with bis-μ-oxo bridges to mimic the OEC in PSII.[10] In addition to SOD and OEC mimics, macrocyclic complexes with manganese in higher oxidation states (mostly III and IV for the resting site) have been shown to be useful for catalytic oxidation reactions.[8]

Herein, we review Mn(III,IV) μ-oxo bridged dinuclear complexes and Mn(III) macrocyclic mononuclear complexes because of their wide usage in biologically relevant applications. Each section would contain detailed figures and tables that allow the reader to easily find specific experimental values along with data regarding the reference and year of when it was reported. The first section of this review focus on provide a historical overview of Mn(III,IV) μ-oxo bridged dinuclear complexes, traditionally used as models for OEC. Examples of classic, openchain ligands are included here to provide a solid comparison to the macrocyclic counterparts; stablishing a historical context for the spectroscopic assignments that are innate to these types of molecules. A more thorough review of open-chain systems can be found elsewhere.[9b,11] The next section of the review will focus on the synthesis, characterization, and applications of Mn(III) mononuclear complexes, which have a broader range of applications compared to the dinuclear counterparts. These mononuclear complexes are also less prevalent in the chemical literature compared to the dinuclear or mononuclear Mn(II) complexes, hence our focus on bringing them to the spotlight in this review. While many manganese complexes are covered within this review, we apologize to the authors of works that might not be included. From an observational standpoint, the early work focused on synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of the complexes. However, more recent publications shown in this review are more application driven.

Within our experience, solid state structures have been used to characterize the active site of many Mn complexes of tetraaza macrocycles used in the literature, but this is not fully representative of solution behavior. Different complexes of Mn are monomers in the solid state, but spectroscopic evidence shows dimer features in solution (or vice versa). With this review, we hope to provide the readers with a comprehensive guideline of spectroscopic and electrochemical features that will allow a more accurate description and identification of the appropriate speciation of Mn according with its application.

Guide to nomenclature in this review:

Complexes in this review are labelled based on order of publication, ligand used, and type of complex formed. For example, a Mn(III,IV) dinuclear complex with cyclam is labelled with a different number than a Mn(III) mononuclear complex with cyclam. Different counterions associated with each complex are denoted using an additional letter between systems of the same ligand set; for example, complexes 1a and 1b are both comprised of the bipy ligand, but the counterions for each complex are different. If a number is written in the text without a letter after it, this is referring to only the cation of the complex not including counterions or solvent molecules,. For several ligands, such as bispicen and tmpa, researchers synthesized ligand derivatives and made metal complexes with the derivatives, these are labelled with a decimal number after the main number, 3.1, 3.2, and so on. All electrochemical potentials have been referenced to NHE for comparison within the series.[12]

2. Mn(III,IV) bis-μ-oxo bridged dimer complexes

Early data gathered on PSII using EXAFS and EPR indicated a bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese complex contained within the OEC. This led to researchers postulating that the OEC contained a dimer of dimers (Figure 1).[1b] Based on this evidence, multiple small molecules containing a bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimer have been produced to mimic the structure of the OEC.[15] Small molecules provide a model that scientist can use to study the most complex enzyme in order to understand some of the fundamental questions regarding its structure and reactivity. As a result, a range of ligands have been explored as scaffolds to form such complexes. This section will discuss the synthesis, characterization, and applications of these historically significant Mn(III,IV) dimers, which originated from open-chain ligands. Here, examples will be given of such studies to lay the groundwork for comparison to aza-macrocyclic based systems reported in the last 50 years.

Figure 1.

(a) Proposed model of OEC published in 1994[13] (b) Crystal structure of OEC at resolution of 1.9 Å, published in 2011.[14]

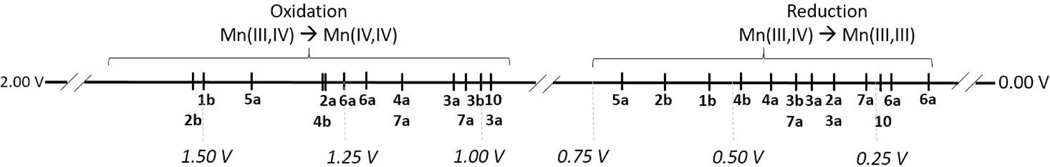

Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the ligand structures and their Mn complexes described herein. Table 1, Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4 contain a list of the references where each complex was reported, along with structural and spectroscopic data. Table 5 contains electrochemical information, which is organized in Figure 4 from more positive potentials to more negative potentials.

Figure 2.

Parent ligands for Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes.

Figure 3.

Synthesis timeline of Mn(III,IV) bis-μ-oxo bridged dimers.

Table 1.

Di-μ-oxo-bndged Mn(III,IV) dimers reported in literature.

| Complex | Year Reported | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1a | [(bipy)4Mn2O2][S2O8]1.5 | 1960 | [15a] |

| 1b | [(bipy)4Mn2O2][ClO4]3·2 H2O | 1960, 1977 | [15a,d] |

| 1 c [a] | [(bipy)4Mn2O2][ClO4]3 | 1972 | [15b] |

| 1d [a] | [(bipy)4Mn2O2][ClO4]3·3 H2O | 1986 | [16] |

| 2a [a] | [(phen)4Mn2O2][PF6]3·CH3CN | 1976, 1986 | [15c,16] |

| 2b | [(phen)4Mn2O2][ClO4]3 • CH3COCH3 | 1977 | [15d] |

| 2c [a] | [(phen)4Mn2O2][ClO4]3• 2 C2H3O2• 2H2O | 1994 | [17] |

| 3 a [a] | [(bispicen)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·3 H2O | 1987 | [18] |

| 3b | [(bispicen)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3 | 1990 | [18] |

| 4a [a] | [(tmpa)2Mn2O2][S2O6]3/2·7 H2O | 1988 | [4] |

| 4b | [(tmpa)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·3 H2O | 1988 | [15h] |

| 4c [a] | [(tmpa)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3 | 2007, 2014 | [5a,19] |

| 5 a [a] | [(tren)2Mn2O2][CF3SO3]3·EtOH | 1988 | [15g] |

| 6a [a] | [(cyclam)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·2 H2O | 1988, 1989 | [1b,15f] |

| 6b [a] | [(cyclam)2Mn2O2][Br]3·4 H2O | 1990 | [20] |

| 6c [a] | [(cyclam)2Mn2O2][S2O6]1·37[S2O3]0.13 | 1990 | [20] |

| 6d | [(cyclam)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3 | 2014 | [21] |

| 7a | [(cyclen)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·2 H2O | 1988 | [15f] |

| 7 b [a] | [(cyclen)2Mn2O2][Cl]3·LiCl·5 H2O | 1992 | [22] |

| 7c | [(cyclen)2Mn2O2][NO3]3 | 1992 | [22] |

| 8a [a] | [(H2O)2(terpy)2Mn2O2](NO3)3 | 1999 | [23] |

| 9a [a] | [(pyclen)2Mn2O2][Cl]3·6 H2O | 2008 | [24] |

| 9 b [a] | [(pyclen)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·4 H2O | 2020 | [25] |

| 10 | [(isocyclam)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·2H2O | 2012 | [26] |

The solid state structure has been reported in literature.

Table 2.

Mn-Mn bond distances within bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimers.

| Complex | MnIII-MnIV [Å] | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| 1c | 2.716 | [15b] |

| 1 d | 2.716 | [16] |

| 2a | 2.700 | [15c,16] |

| 3a | 2.659 | [15e] |

| 4a | 2.643 | [4] |

| 4c | 2.624 & 2.626[a] | [5a] |

| 5a | 2.679 | [15g] |

| 6a | 2.741 | [1b] |

| 6b | 2.731 | [20] |

| 6c | 2.729 & 2.738[a] | [20] |

| 7b | 2.694 | [22] |

| 8a | 2.723 | [23] |

| 9a | 2.6814 | [24] |

| 9b | 2.712 | [25] |

Contains two Mn2O2 species within asymmetric unit, both Mn- distances are reported.

Table 3.

Mn2O2 vibrational frequencies of bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimers.

Table 4.

Electronic spectra of bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimers

| Complex | λmax [nm],(ε, Mol−1 cm−1) | Solvent | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1b | 525 (530), 555 (455), 684 (561) | bipy buffer | [15d] |

| 2a | 523 (580), 550 (460), 680 (550), 800 (sh) | solid state | [16] |

| 2b | 525 (509), 555 (427), 684 (553) | phen buffer | [15d] |

| 3b | 386 (1355),432 (1270), 553 (569), 655 (526), 805 (250) | H2O | [18] |

| 4b | 443 (1490), 561 (760), 658 (620) | CH3CN | [15h] |

| 5a | 380 (1170), 428 (sh), 526 (sh), 548 (440), | CH3CN | [15g] |

| 590 (sh), 638 (sh), 680 (570) | |||

| 6a | 550 (760), 650 (780) | H2O | [1b,15f] |

| 556 (750), 560 (sh), 646 (760), 800 (125) | CH3CN | ||

| 6b | 550 (750), 644 (770), 800 (sh) | N-methylformamide | [20] |

| 7a | 556 (700), 650 (890), 740 (880) | H2O | [15f] |

| 7b | 381 (1741), 430 (sh 1275), 554 (535), 658 (676), 696 (666) | H2O | [22] |

| 379 (1769), 430 (sh 1289), 554 (550), 652 (678), 697 (667) | N-methylformamide | ||

| 9b | 382(652), 555(181), 665(211), 800 (sh) | H2O | [25] |

| 10 | 548, 562(760), 652(750) | H2O | [26] |

Table 5.

Results of cyclic voltammetry of bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimers.

| Complex | MnIII,IV/MnIV,IV [V] vs. NHE | MnIII,IV/MnIII,III [V] vs. NHE | Solvent and Electrolyte | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 1 b | 1.50 | 0.54 | CH3CN, 0.3 M Et4NCIO4 | [15d] |

| 2a | 1.28 | 0.34 | CH3CN, 0.1 M Et4NCIO4 | [16] |

| 2b | 1.51 | 0.59 | CH3CN, 0.3 M Et4NCIO4 | [15d] |

| 3a | 0.99 | 0.38 | H2O (pH 7.0), 0.1 M NaCIO4 | [15e] |

| 1.06 | 0.35 | CH3CN, 0.1 M NaCIO4 | ||

| 3b | 1.00 | 0.39 | H2O (pH 7), 0.1 M NaClO4 | [18] |

| 4a | 1.14[a] | 0.44[b] | H2O (pH 6.9) | [4] |

| 4b | 1.29 | 0.49 | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NPO4 | [15h] |

| 5a | 1.40 | 0.66 | [c] | [15g] |

| 6 a | 1.25 | 0.13 | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | [1b,15f] |

| 1.22 | 0.22 | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | ||

| 7a | 1.14 | 0.39 | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | [15f,22] |

| 1.04 | 0.27 | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NPO4 | ||

| 10 | 0.99 | 0.24 | H2O (pH 7.0), 0.1 M KCl | [26] |

Quasi-reversible oxidation wave.

Irreversible reduction event.

Details not available.

Figure 4.

Oxidation and reduction values for various bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimers in literature.

2.1. Bipy and phen Mn(III,IV) dimers

The first bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimer [(bipy)4MnIII,IV2O2][S2O8]1.5 (1a) was reported by Nyholm and Turco in 1960 (Figure 3, Table 1). This was accomplished by adding molten bipy and solid K2S2O8 to a suspension of MnSO4 ·4H2O in warm water.[15a] The product was isolated as large greenish-black crystals and was postulated to contain two manganese centers in different high valent oxidation states (III, IV).[15a] A metathesis reaction was used to obtain the corresponding perchlorate [(bipy)4MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·2H2O (1b) counterpart. In 1972, Plaksin et al. reported the anhydrous congener of 1b [(bipy)4MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 (1c) as well.[15b] The solid state structure for the novel bimetallic complex 1c suggested that the manganese centers were in two different oxidation states (III, IV) based on bond lengths and the significant Jahn-Teller distortion exhibited by the Mn(III) atom.[15b] The Mn Mn bond distance reported for 1c was 2.716 Å, similar to the Mn Mn bond distance observed in the OEC (2.7 Å) (Table 2).[15b]

Uson et al. reported the first phen based bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimer in 1976: [(phen)4MnIII,IV2O2][PF6]3 ·CH3CN (2a).[15c,d] The following year, Cooper and Calvin described the synthesis of [(phen)4MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·CH3COCH3 (2b) in which the dropwise addition of an aqueous solution of KMnO4 to a solution of Mn(OAc)2 ·4H2O and phen resulted in a green powder (2b).[15d] Cooper and Calvin examined both 1b and 2b using IR, cyclic voltammetry, and UV-vis, (Table 3 and Table 4; Figure 3and Figure 4).[15d] These characterization techniques offered insight about the interaction of the binuclear Mn species in solution. A stretching frequency of 688 cm −1 was observed for the bipy dimer, but upon recrystallization in H218O at 80°C a new band (shoulder) appeared at 676 cm −1.[15d] No other bands were observed to shift. Therefore, the stretching frequencies of 688 cm −1 (1b) and 686 cm −1 (2b) were assigned as the vibrational modes of the Mn2O2 core.[15d] Additionally, it was concluded that both 1b and 2b were Class II compounds in the classification scheme of Robin and Day for mixed valent compounds, based on the electronic spectra and previously obtained crystal structure of 1b.[15d,27] Class II compounds have weak interactions between the metal ions. In addition to the typical absorbance bands observed from manganese complexes, the electronic spectrum also exhibits a new absorption band attributed to a photon-driven electron transfer (intervalence transfer or IT) between the two manganese metal ions.[15d,27] In contrast, Class I compounds have almost no interaction between the metal ions, while Class III compounds are considered fully delocalized and resonance stabilized compounds.[15d,27] The electronic spectra for both 1b and 2b exhibited absorbance bands at 525, 555, and 684 nm.[15d] Cooper and Calvin assigned the 525 and 555 nm absorbance bands as d-d transitions, based on small extinction coefficient value. The 684 nm absorbance band had been previously assigned as a ligand to metal charge transfer band (LMCT) from the oxygen to the Mn(III) metal center.[15d,28] This lower energy band was later reassigned by Suzuki et al. as the LMCT from the oxygen to the Mn(IV) metal center.[15h] In addition, an 830 nm shoulder extending from the 684 nm absorbance band was observed; this would later be identified as an IT band by Stebler et al.[16] Cooper and Calvin also investigated 1b and 2b using cyclic voltammetry. For both complexes, two redox events were observed: a reversible anodic wave corresponding to the oxidation of MnIII,IV/MnIV,IV (E1/2 =1.50 V vs. NHE for 1b and E1/2 = 1.51 V vs. NHE for 2b) and a reversible cathodic wave corresponding to the reduction of MnIII,IV/MnIII,III (E1/2 =0.54 V vs. NHE for 1b and E1/2 =0.59 V vs. NHE for 2b).[15d] The following year, Cooper and Calvin published EPR investigations of 1b and 2b, which exhibited a 16-line spectrum at 18 K and average g values of 2.003.[29] The small g anisotropy suggested that the ground state of the Mn(III) (d4) ion was high-spin.[29] Subsequent, EPR studies on 1b and 2b confirmed that the manganese ions were inequivalent in solution.

Although the initial synthesis of 2a was reported in 1976, a complete solid state structure of a phen Mn(III,IV) dimer was not published until 1986. Stebler et al. reported the crystal structure for a [(phen)4MnIII,IV2O2][PF6]3 ·CH3CN (2a) complex with static disorder between the two manganese centers.[16] The measured bond distance between the Mn Mn atoms was 2.700 Å (100 K) and 2.695 Å (200 K). At both temperatures, the bond distances are slightly shorter than the Mn Mn distance in 1c or 1d (both 2.716 Å) but still comparable to Mn Mn distances found in the OEC (2.7 Å).[16] In addition to the solid state structure, Stebler et al. also performed UV-vis, and cyclic voltammetry measurements on 2a.[16] The electronic spectrum and cyclic voltammogram of the newly synthesized phen dimer were consistent with those previously reported by Cooper and Calvin. Manchanda et al. successfully employed bromate as an oxidant, in place of permanganate, to obtain the phen Mn(III,IV) dimer [(phen)4MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·2 C2H3O2 ·2H2O (2c) in 1994.[17] X-ray diffraction results showed crystallographically distinct Mn(III) and Mn(IV) ions and a Mn Mn bond distance of 2.711 Å, unlike the 2a solid state structure reported by Stebler et al. that contained static disorder between the two manganese centers.[17]

Several groups investigated the water oxidation catalytic abilities of the various complexes of 1 and 2 described above. The first activity was reported by Gref et al. in 1984, showing that the redox couples of complexes 1 and 2 were suitable for the catalytic anodic oxidation of benzyl ethers and benzyl alcohols with high selectivity.[30] Inspired by this work, Ramaraj et al. reported evidence of complexes 1 and 2 catalyzing water oxidation chemistry for the first time. Formation of oxygen bubbles were observed when the bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers were suspended heterogeneously in water with a chemical oxidant (CeIV).[31] In contrast, no measurable oxygen evolution was observed when complexes 1 or 2 were completely dissolved in water (i.e. in a homogeneous solution) with CeIV.[31] Additional investigation of heterogenous water oxidation revealed that stirring the reaction mixture lead to more O2 formation and that the pH of the solution did not affect the water oxidation process.[31] Ramaraj et al. also found that complex 1 was a more efficient catalyst than complex 2. This was consistent with cyclic voltammetry results that indicated complex 1 was easier to oxidize than 2.[31]

Ramaraj et al. published additional results with complex 1 adsorbed onto clay, prepared by mixing complex 1 with Kaolin clay in water, and its water oxidation ability.[32] Findings for this heterogeneous catalyst were similar to what was observed in previous studies by the same group. O2 bubbles formed on the surface of the clay in the presence of CeIV using complex 1 with clay.[32] Decomposition of complex 1 was observed if too much catalyst was adsorbed onto the clay surface (>3.6 μmol/150 mg Kaolin); increase of complex 1 on the clay surface led to an increase in oxygen evolution, but once a certain threshold was reached decomposition was observed. Permanganate ions (MnO4 ) were appointed as the decomposition product mentioned before, which was detected by UV-vis analysis of the solution after catalysis.[32] Following the discovery that bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers had the potential to act as water oxidation catalysts, there was a large increase in the number of publications dedicated to manganese dimers in the late 1980s.[1b,4,15e–g,33]

2.2. Bispicen Mn(III,IV) dimers

After the discovery, synthesis, and characterization of the novel bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimer complexes with phen and bipy ligands more groups began to report Mn(III,IV) dimers with a range of multidentate nitrogen-containing ligands. In 1987, Collins et al. reported a novel bispicen dimer complex [(bispicen)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·3H2O (3a) obtained by combining MnCl2 ·4H2O, bispicen·4HCl, NaHCO3, and H2O2.[15e] As shown in Figure 3, complex 3a deviated from the previously synthesized complexes 1 and 2 based on the number of ligands that comprise the complex. Both 1 and 2 contained four individual bidentate ligands, two ligands bound to each manganese atom. However, 3 contained two tetradentate ligands (one ligand bound to each manganese atom). The Mn Mn bond distance in the bispicen dimer was measured to be 2.659 Å within the solid state structure of 3a; this distance was considerably shorter than the Mn Mn bond distances of complex 1a/1d (2.716 Å) and 2a (2.700 Å).[15e] The redox chemistry of 3a is similar to 1 and 2 and corresponds to the quasi-reversible anodic oxidation of MnIII,IV/MnIV,IV (E1/2 =0.99 V vs. NHE in water; E1/2 =1.06 vs. NHE in acetonitrile) and the quasi-reversible cathodic reduction of MnIII,IV/MnIII,III (E1/2 =0.38 vs. NHE in water; E1/2 =0.35 vs. NHE in acetonitrile).[15e] Collins et al. found that 3a was easier to oxidize to the Mn(IV,IV) form based on more negative anodic waves of 3a compared to either complex 1 or 2.[15e]

In 1990, Goodson et al. described another bispicen dimer [(bispicen)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 (3b).[18] The electronic spectrum of 3b was similar to complexes 1 and 2, with absorbance bands at 386, 432, 655, and 805 nm. The cyclic voltammetry measure ments obtained by Goodson et al. were congruent to those initially reported by Collins et al. Two quasi-reversible waves were observed for the complex corresponding to the reduction and oxidation of the Mn(III,IV) dimer (E1/2 =1.00 V vs. NHE (oxidation); E1/2 =0.39 V vs. NHE (reduction) in water).[18] EPR studies of 3b exhibited a 16-line hyperfine pattern, which is assigned as two antiferromagnetically coupled manganese(III,IV) ions.

Goodson et al. described a new library of bispicen derived bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers (3.1a–3.5a) (Table 6, Figure 5).[34] The complexes were synthesized using a similar approach to Collins et al. Only small changes in the redox potentials of the bispicen derivative complexes were observed compared to the original bispicen complex, with maximum shifts in redox potentials of 49 mV.[34] A bispicen derivative complex was also reported in 1998, by Horner et al.[(N,Nbispicen)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·CH3CN (3.6a).[35] Although technically an isomer of bispicen, N,Nbispicen is a tripodal ligand that is similar to others such as tmpa or tren.[35] Horner et al. found an unusual feature of this novel N,Nbispicen dimer. The crystal structure of complex 3.6a indicated that the N,Nbispicen ligands were in the cis configuration relative to the Mn2O2 core; the two primary amino groups from the ligand were situated on the same side of the Mn2O2 plane. Technically, this indicated that both a cis and trans bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimer could be synthesized, although only the cis isomer was isolated.Despite this interesting result the characterization of complex 3.6a was analogous to previously reported bispicen derivatives.[35]

Table 6.

Bispicen derived Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes.

| Complex | Coordinating Ligand | Metal Complex | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 3a | N,N’-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,2-diaminoethane (bispicen) | [(bispicen)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3·3 H2O | [15e] |

| 3b | N,N’-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,2-diaminoethane (bispicen) | [(bispicen)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3 | [18] |

| 3.1a | N,N’-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,2-propanediamine (bispicpn) | [(bispicpn)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3·5 H2O | |

| 3.2 a | N,N’-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-2,3-butanediamine (bispicbn) | [(bispicbn)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3]·4 H2O | |

| 3.3 a | N,N’-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,2-cyclohexanediamine (bispichxn) | [(bispichxn)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3]·5 H2O | [34] |

| 3.4 a | N,N’-bis(1-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)-1,2-ethanediamine (Me2bispicen) | [(Me2bispicen)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3]·H2O | |

| 3.5 a | N,N’-bis(1-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)-1,3-propanediamine (Me2bispictn) | [(Me2bispictn)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3 | |

| 3.6 a | N,N-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)-1,2-diaminoethane (N,Nbispicen) | [(N/Nbispicen)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·CH3CN | [35] |

| 3.7 a | N,N’-dimethyl-N,N’-bis(2-pyndylmethyl)ethane-1,2-diamine (mep) | [(mep)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3 | [36] |

| 3.8 a | N,N’-dimethyl-N,N’-bis(2-pyridylmethyl)propane-1,3-diamine (mpp) | [(mpp)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3 | |

Figure 5.

Bispicen and derivatized ligands.

Almost 20 years after the original synthesis of a bispicen Mn(III,IV) dimer, Hureau et al. reported the first method for electrochemically converting Mn(II) monomer complexes into Mn(III,IV) dimers (3.7a and 3.8a).[36] In the presence of 2,6dimethylpyridine and the absence of excess chloride ions, cis[(mep)MnIICl2] and cis[(mpp)MnIICl2] were electrochemically oxidized to [(mep)2MnIII,IV2O2]3+ (3.7a) and [(mpp)2MnIII,IV2O2]3+ (3.8a) using bulk electrolysis.[36] The authors noted that no Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes were observed in the absence of base after bulk electrolysis. It was hypothesized that the 2,6-dimethylpyridine neutralized the protons generated by the formation of the oxo bridges, which originated from the water molecules, thus facilitating formation of the Mn(III,IV) dimer in solution. The new species were validated with EPR, cyclic voltammetry, UV-vis, and XRD (complex 3.8a only). Each characterization method exhibited characteristic signs of a Mn(III,IV) dimer in solution consistent with the studies described above.

2.3. Tmpa Mn(III,IV) dimers

Tmpa is a popular ligand for use in biomimetic complexes because it is easily synthesized and exhibits a versatile coordination chemistry.[5a,37] In 1988, both Towle and Suzuki et al. independently synthesized two tmpa dimers: 4a ([(tmpa)2MnIII,IV2O2][S2O6]3/2 ·7H2O) and 4b ([(tmpa)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·3H2O), respectively.[4,15h] The two tmpa dimers were composed of two tetradentate ligands with one tmpa ligand bound to each manganese atom, similar to complex 3.[4,15h] Both groups synthesized the tmpa Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes in a similar manner through the combination of MnSO4 ·H2O or Mn(ClO4)2 ·6H2O with tmpa and H2O2.[4,15h] Suzuki et al. performed cyclic voltammetry, UV-vis, and EPR to characterize the structure in solution. Following the procedure of Ramarai et al. 4b was subjected to water oxidation catalysis, but the complex did not present such oxidation. Additionally, Towle et al. were also able to model the solid state structure through XRD, and reported additional cyclic voltammetry measurements.[4] The electronic spectrum showed similar (442, 562, and 658 nm) bands compared to previously reported bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers. Unlike complexes 1 and 2, complex 4b did not exhibit a shoulder near 830 nm, which had previously been assigned as an IT band.[15h] Suzuki et al. hypothesized that this was due to the smaller degree of delocalization within 4b compared to either 1 or 2.[15h] However, the EPR spectrum did exhibit the classic 16-line hyperfine pattern expected for an antiferromagnetically coupled Mn(III,IV) dimer with two inequivalent manganese ions.[15h] The solid state structure of the tmpa dimer 4a and the Mn Mn bond distance was measured to be 2.643 Å, which was considerably shorter than previously synthesized bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers.[4] Additionally, the cyclic voltammogram revealed a quasi-reversible oxidation wave corresponding to MnIII,IV/MnIV,IV (E1/2 =1.14 V vs. NHE) and an irreversible reduction from MnIII,IV/ MnIII,III (Epeak =0.44 V vs. NHE).[4] Towle et al. hypothesized that the reduction was not reversible because of the presence of a dithionate ion, unlike the tmpa complex 4b.[4,15h]

Oki et al. expanded the synthesis and characterization of Mn(III,IV) dimers with several different tmpa derivatives. Their goal was to synthesize a library of chemically altered tmpa Mn(III,IV) complexes to modify the stereochemical and electronic properties of the metal centers.[38] Complexes 4.1a–4.4a (Table 7, Figure 6) were synthesized following the procedure of Towle et al.[4] Oki et al. characterized the complexes using UVvis, cyclic voltammetry, EPR and XRD (for complex 4.1a only). The results obtained from the characterization methods showed evidence of the presence of an Mn2O2 core and were similar to those obtained for previous tmpa Mn(III,IV) complexes.[4,15h] Substitution within the alkyl arms of the ligand had little impact on the redox potentials, however, substitution at the 6-position of the pyridine ring caused a significant shift, greater than 200 mV.[38] Each dimer was tested for the ability to catalyze the epoxidation of cyclohexene by iodosobenzene, an area of intense research with Mn(III) mononuclear complexes as noted in the report. All the complexes tested (4.1a, 4.3a, and 4.4a) exhibited preferential catalytic activity toward the epoxidation of cyclohexene.[38] In addition, methyl substitution at the 6position of the pyridyl ring resulted in a significant increase in the yield of epoxide.[38] Due to the success of this work, other research groups have investigated the effects of steric substitution on structural, spectroscopic, and electronic properties of Mn(III,IV) complexes with tmpa derived ligands.[39]

Table 7.

Tmpa derived Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes.

| Complex | Coordinating Ligand | Metal Complex | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 4a | tris(2-methylpyridyl)amine (tmpa) | [(tmpa)2Mn2O2][S2O6]3/2·7H2O | [4] |

| 4b | tris(2-methylpyridyl)amine (tmpa) | [(tmpa)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3·3 H2O | [15h] |

| 4.1a | (2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (pmea) | [(pmea)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3 | |

| 4.2 a | (1-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)(2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (Mepmeal) | [(Mepmea1)2Mn2O2][CIO4]3 | [38] |

| 4.3 a | ((6-methyl-2-pyridyl)methyl))(2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl)(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (Mepmea2) | [(Mepmea2)Mn2O2][CIO4]3 | |

| 4.4 a | ((6-methyl-2-pyridyl)methyl)bis(2-pyridylmethyl)amine (Mepmea3) | [(Mepmea3)Mn2O2][CIO4]3 | |

| 4.5 a | (bis[2-(2-pyridyl)ethyl]-2-pyridylmethylamine (pmap) | [(pmap)2Mn2O2][ClO4]3·CH3CN | [37] |

Figure 6.

Tmpa and related ligands

In 2000, Schindler et al. made modifications to the parent tmpa ligand by increasing the arm lengths of the alkyl chains connected to the pyridine units. Pmea, contains two methyl pyridyl moieties and one ethylpyridyl moiety attached to the central nitrogen (Figure 6); Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes with this ligand have been well characterized by other reports.[38] Pmap and tepa are also derivatives of the parent tmpa ligand.[37] Pmap contains two ethylpyridyl moieties and one methylpyridyl moiety attached to a central nitrogen, while tepa contains three ethylpyridyl moieties attached to central nitrogen. Increasing arm length of the alkyl chains led to an increase in the size of the chelate ring attached to the metal center, which was postulated to favor lower oxidation states for the metal ion attached, i.e. Mn(III,III) complexes. Therefore, high valent Mn(III,IV) complexes with increased alkyl chain lengths using the pmap and tepa ligands were pursued. The [(pmap)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·CH3CN (4.5a) complex was isolated by reaction of pmap with Mn(ClO4)2 and H2O2.[37] The solid state structure of the complex was modeled by XRD. A considerable change in Mn Mn bond lengths between the three different Mn(III,IV) dimers was observed: complex 4a (2.643 Å),[4] complex 4.1a (2.693 Å),[38] and complex 4.5a (2.738 Å).[37] The increasing Mn Mn bond distances directly correlate to the increase in chelate ring size within the Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes.[37] Complex 4.5a was also characterized utilizing traditional methods to validate the Mn(III,IV) dimer.[37] Conversely, attempts to synthesize a Mn(III,IV) dimer with tepa were unsuccessful. Schindler et al. postulated that the Mn Mn distance was too large for a μ-oxo bridge to form.[37]

In 2007, Shin et al. reported the [(tmpa)2Mn2(μ-Cl)2]2+ dimer as a model of chloride-inhibited superoxidized MnCAT (III,IV), which is known to be catalytically inactive.[5a,40] The H2O2 dismutation activity was tested against several other manganese-containing complexes, including a [(tmpa)MnIICl2]2+ monomer and a [(tmpa)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 dimer (4c). The core complex [(tmpa)2MnIII,IV2O2]3+ (4) had been previously prepared by others, but Shin et al. were able to synthesize complex 4c using a slightly different methodology.[4,33a] All three complexes, [(tmpa)2Mn2(μ-Cl)2]2+, [(tmpa)MnCl2]2+, [(tmpa)2MnIII,IV2O2]3+ (4c), successfully shown catalase activity: conversion of H2O2 to O2.[5a] Shin et al. followed up this work by an investigation of the conversion of [(tmpa)2Mn2(μ-Cl)2]2+ to [(tmpa)2MnIII,IV2O2]3+ by adding stoichiometric amounts of H2O2 and subsequent catalysis of H2O2 disproportionation.[41]

A model for the water oxidation and recovery systems of the OEC was reported by Yatabe et al. in 2014. Photo-irradiation of the [(tmpa)2MnIII,III2O2]2+ dimer with DTBBQ and NEt3 resulted in a Mn(II)-semiquinonato complex ([MnII(tmpa)(DTBSQ)]+).[19] The Mn(III,III) [(tmpa)2MnIII,III2O2]2+ dimer was regenerated when the Mn(II)-semiquinonato complex was exposed to O2. Yatabe et al. hypothesized that the cycle between the Mn(III,III) [(tmpa)2MnIII,III2O2]2+ dimer and Mn(II)-semiquinonato complexes would potentially be a good model for the photo-damaged OEC, based on several biological studies suggesting that the photo-damaged OEC contains reduced Mn(II). In addition, Yatabe et al. also synthesized a Mn(III,IV) tmpa dimer based on the procedures described previously by both Towle et al. and Suzuki et al.[4,19,33a] This complex was one of several bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers explored as models of the water oxidation reaction of the OEC.[19] Along with the Mn(III,IV) dimer [(tmpa)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 (4c), the group also synthesized the previously discussed Mn(III,III) dimer [(tmpa)2MnIII,III2O2]2+, and a Mn(IV,IV) [(tmpa)2MnIV,IV2O2]4+ dimer.[19] UV-vis, and EPR were utilized to characterize each complex. The Mn(III,III), Mn(III,IV), and Mn(IV,IV) complexes were also adsorbed onto clay and tested for the ability to heterogeneously oxidize water using CeIV. All three dimer complexes catalytically evolved O2 from H2O, albeit in very modest amounts (turnover numbers ranging from 1.9–2.6 over 500 s).[19] The O2 formation gradually plateaued due to the formation of MnO4, which was validated with UV-vis spectroscopy.[19] Ultimately, the various manganese complexes reported by Yatabe et al. were brought together to form a tandem reaction, modelling the photoinhibition, recovery, and water oxidation steps that takes place within the OEC.[19]

2.4. Tren Mn(III,IV) dimer

A novel bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimer using tren was described in 1988 by Hagen et al.[15g] [(Tren)2MnIII,IV2O2][CF3SO3]3 ·EtOH (5a) was the first Mn (III,IV) complex to be isolated with a ligand that did not contain pyridine moieties. Complex 5a was synthesized by exposing a mixture of Mn(CF3SO3)2 ·CH3CN, tren, and CH3CN to air for two hours, which resulted in a green solution that eventually turned brown. Interestingly, this is one of the earliest examples of no external oxidant added to form the Mn(III,IV) dimer complex in a report (simply atmospheric air instead). Hagen et al. characterized this complex using XRD, IR, UV-vis, cyclic voltammetry, and EPR; which had become standard for the characterization of these bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers (Tables 2–5). The complex crystalized as [(tren)2MnIII,IV2O2][CF3SO3]3 ·EtOH (5a) and the Mn Mn distance was found to be 2.679 Å (Tables 1–2). This bond distance was intermediate compared to its predecessors: shorter than both complexes 1 and 2, but longer that Mn Mn distance found in complexes 3 and 4. IR revealed a Mn2O2 vibration at 694 cm 1, which was the highest vibrational frequency recorded to date for these bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers. The electronic spectrum of this tren complex in CH3CN contained maxima at 380, 428(sh), 526(sh), 548, 590, 638, and 680 nm.[15g] Unlike 1 and 2, there was no broad band observed at 800 nm in the electronic spectrum of the tren complex, suggesting that the degree of delocalization between the two metal ions was lesser than either complex 1 or 2.[15,33a] Additionally, the cyclic voltammogram revealed two quasi-reversible redox couples corresponding to reduction of Mn III,IV/MnIII,III (E1/2 =0.66 V vs. NHE) and oxidation of MnIII,IV/MnIV,IV (E1/2 =1.40 V vs. NHE). Interestingly, the values of these redox couples were significantly higher than either complex 1 or 2, meaning that complex 5a was easier to oxidize in solution.[15g] EPR of 5a revealed the expected 16-line pattern.[15g]

2.5. Cyclam and cyclen Mn(III,IV) dimers

In addition to the already summarized open-chain ligand complexes, Brewer et al. synthesized two novel macrocyclic bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers in 1988.[15f] One dimer was composed of two cyclam ligands [(cyclam)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·2H2O (6a); the other dimer was composed of two cyclen ligands [(cyclen)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·2H2O (7a). These two novel Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes were synthesized by air oxidation of aqueous solutions containing the ligand (either cyclen or cyclam) and Mn(ClO4)2.[15f] Although both cyclen and cyclam coordinate in the same fashion through the 4 nitrogen atoms contained in the backbone, the differences in cavity size of the 12- vs. 14-membered rings, respectively, bring about slightly different characteristics for each metal complex. The IR spectrum showed bands in the region now expected for an Mn2O2 vibration: 6a (680 cm 1) versus 7a (689 cm −1). Likewise, complex 6a exhibited absorbance bands at 550 and 650 nm (in water) and complex 7a exhibited absorbance bands at 556, 650, and 740 nm (in water). These different electron absorption spectra are consistent with a difference in the coordination chemistry around the metal center caused by the change of the cavity size. Additionally, both complexes 6a and 7a exhibit two redox events, a reduction corresponding to MnIII,IV/MnIII,III (6a, E1/2 =0.22 V; 7a, E1/2 =0.39 V; vs. NHE) and an oxidation corresponding to MnIII,IV/ MnIV,IV (6a, E1/2 =1.22 V; 7a, E1/2 =1.14 V; vs. NHE). These results indicate that the cyclen complex 7a is both easier to oxidize and easier to reduce than the cyclam dimer 6a. Brewer et al. hypothesized that the electrochemical properties of each Mn(III,IV) dimer were influenced by steric factors, including the ability for the cyclam macrocycle to better accommodate the manganese metal center.[15f] Brewer et al. also investigated the capability of complex 6a to perform water oxidation catalysis, along with a complete characterization of the novel Mn(III,IV) dimers. Although the original electrochemical characterization of complex 6a took place in rigorously dried acetonitrile, the oxidative peak current (ipa) for the wave at 1.22 V (vs. NHE) increased markedly upon addition of water to the solution (1.5% v/v water-acetonitrile). No redox events were observed with the mixed solvents in the absence of complex 6a, thus confirming that 6a was the source of the increase in current. The authors concluded that this growth in the oxidative peak current was consistent with water oxidation in the chemical step at the electrode surface because the observed peak current was much larger than what was expected for a one-electron oxidation of complex 6a.[15f]

A solid state structure for complex 6a was reported a year later in 1989 by the same group.[33b] The Mn Mn bond distance was measured to be 2.731 Å. Additionally, Brewer et al. gathered evidence suggesting that water was the source of the bridging oxygen atoms contained within the Mn2O2 core, which had not been established to date. Until this point, most Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes were synthesized using external oxidants, such as K2S2O8, KMnO4, or H2O2 that could act as oxygen donors.[1b] By electrochemically synthesizing complex 6a Brewer et al. were provided with evidence that H2O was, in fact, the source of the bridging oxygen atoms. An acetonitrile solution that contained 2% water (v/v), 1 eq. of Mn(CF3SO3)2, 1 eq. of cyclam, and 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 was deuterated before potential was applied.[1b] The colorless solution developed a green color over 2 h and the corresponding electronic spectrum of the solution was characteristic of an Mn(III,IV) dimer.[1b] The only available source for the oxo bridges was the water in the solution; thus, suggesting that H2O was the source of the oxo bridges within the Mn2O2 core. A strong band was observed at 679 cm −1 in the IR spectrum of 6a and assigned to the Mn2O2 core. Synthesis of complex 6a in H218O split this band into two weaker peaks (681 cm −1 and 679 cm −1), thus confirming the 679 cm −1 band was due to the vibration of the Mn2O2 core. Cooper and Calvin observed the same behavior with complex 1b.[1b,15d]

Two additional Mn(III,IV) cyclam dimer structures were reported by Goodson et al. in the following year: [(cyclam)2MnIII,IV2O2][Br]3 ·4H2O (6b) and [(cyclam)2MnIII,IV2O2][S2O6]1.37[S2O3]0.13 (6c).[20] The complex Mn Mn bond distances were comparable to one another, 6b (2.741 Å) and 6c (2.729 and 2.738 Å, with the crystal having two independent dimers within the unit cell).[20] It wasn’t until 1992 that a solid state structure of a Mn(III,IV) cyclen dimer was reported, [(cyclen)2MnIII,IV2O2][Cl]3 ·LiCl·5 H2O (7b).[22] The Mn Mn bond distance in the cyclen complex was measured to be 2.694 Å, much smaller compared to the Mn(III,IV) cyclam complexes. The shorter Mn Mn bond distance within the cyclen complex is consistent with the different ring sizes of cyclam and cyclen. Cyclam, a 14-membered ring, is larger, thus allowing for a better fit within the macrocyclic cavity for the manganese ion. Whereas cyclen, a 12-membered ring, has a smaller cavity size that is not as accommodating to the size of the manganese ion. Hence, the manganese ions sit more out of plane in 7, and closer to one another than in the cyclam complex 6. UV-vis, cyclic voltammetry, and IR also revealed slight differences between the two complexes. Expanding on this work, several other groups synthesized Mn(III,IV) cyclen and cyclam dimers in the early 2000s.[42]

In 2014, Nakamori et al. reported the synthesis of a monomeric Mn(II)-semiquinonato complex as a model for elucidating the function of the OEC in PSII.[21] This Mn(II)semiquinonato complex was synthesized by the reaction of an Mn(III,IV) cyclam dimer[(cyclam)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 (6d) with p-hydroquinone. Complex 6d could be regenerated by oxygenating the Mn(II)-semiquinonato complex. Nakamori et al. conducted several isotopic labeling studies to determine the source of the oxo bridges when the Mn(II)-semiquinonato complex was oxygenated to complex 6d. In one experiment, they used 18O2 as an oxidation source instead of 16O2, ESI-MS results indicated that two 18O atoms (from the 18O2) were incorporated into the μ-oxo bridge within complex 6d.[21] ESI-MS results from a cross-over experiment that used 50% 16O2 and 50% 18O2 showed complexes with cores consisting of Mn216O2, Mn216O18O, and Mn218O2 were formed in a 1:2:1 ratio.[21] Finally, complexes of 6d were exchanged for H2O oxygen atoms, which was confirmed by additional isotopic labelling experiments using H218O. When an excess amount of H218O was added to complex 6d in CH3CN the 16O atoms incorporated into the μ-oxo bridge were exchanged for 18O atoms derived from the H218O.[21] Evidence from the isotopic labelling studies lead Nakamori et al. to contradict what Brewer et al. had hypothesized regarding the source of the bridging oxygens.[1b,21] Nakamori et al. stated that the source of the bridging oxygen atoms within Mn(III,IV) dimer complexes originated with O2, not H2O as was previously proposed.[1b,21] It was noted that because of the fast exchange of the oxo ligands with H2O oxygen atoms, this was an understandable assignment made by Brewer et al.

2.6. Terpy Mn(III,IV) dimers

In 1999, Limburg et al. developed a model complex for the O O bond formation that takes place in the OEC of PSII.[23] It was the first reported bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimer that served as a structural model of the OEC by catalytically forming O O bonds.[23,43] It had been postulated previously that a Mn-oxo species was formed as an intermediate during photosynthetic water oxidation; the terminal oxo ligand within the OEC was thought to be formed by the abstraction of O atoms from a water molecule bound to an manganese ion.[23] Therefore, Limburg et al. designed and synthesized a model bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimer with available sites for solvent coordination that provided a place for the formation of an Mn=O intermediate.[23] [(H2O)2(terpy)2MnIII,IV2O2][NO3]3 ·6H2O (8a) was synthesized by reacting KHSO5 with Mn(II) or Mn(III) complexes containing the terpy ligand.[23] The solid state structure of 8a provided a 2.723 Å Mn Mn bond distance.[23] Of course, the most notable feature of complex 8a were the exchangeable aqua ligands coordinated to each of the manganese ions; this unique configuration was a result of using meridionally coordinated terpy ligands. Upon adding complex 8a to an aqueous solution of NaClO, O2 formation was observed with an initial rate of 12±2 mol/h per mole of complex 8a.[23] A mechanism involving a Mn=O intermediate was determined using 18O labeling and following the O2 evolution via mass spectrometry. The catalytic reaction ceased after complex 8a was completely disproportionated to permanganate over several hours; isosbestic points at 497 and 583 nm were consistent with the formation of MnO4−.[23] Based on this evidence, a mechanism for the formation of O2 by the reaction of complex 8a with NaClO were proposed. Several years after the initial report of this novel Mn(III,IV) dimer 8a, Limburg et al. compared the mechanisms of O2 evolving reactions of 8a, KHSO5, and NaClO, stating that it goes through similar paths and thus validating some of the earlier work done with NaClO.[43]

Following the original synthesis of complex 8a, Yagi et al. reported the ability of the complex to evolve O2 from water when adsorbed onto clay,[44] making it a heterogeneous water oxidation catalyst. No O2 evolution was observed using CeIV as an oxidant with 8a in solution. This finding contrasted with what Limburg et al. had previously reported regarding O2 evolution being observed using 8a and NaClO or KHSO5 as oxidants. Conversely, a significant amount of O2 was produced (turnover number of 13.5±1.1) when 8a was adsorbed onto Kaolin or Montmorillonite clay with CeIV added to the aqueous suspension.[44] 18O-labeling experiments revealed that the O2 evolved was derived exclusively from water, thus validating water oxidation activity.[44] To further investigate a potential mechanism for the catalytic reaction, the authors characterized the 8a/clay mixture. The diffuse reflectance spectrum of 8a/ clay indicated a Mn(IV,IV) species rather than a Mn(III,IV) species. This result suggested that complex 8a was most likely oxidized to Mn(IV,IV) upon adsorption onto the clay. Complex 1 is comparable to complex 8a but contains no terminal water ligands attached to the metal centers. Analysis of each complex’s initial O2 evolution rates (νO2 mol/s) suggested that the terminal water ligands were involved in the catalytic water oxidation of complex 8a.[44] Following this study of the first heterogeneous water oxidation catalyst utilizing a Mn(III,IV) terpy complex, a range of additional studies with Mn(III,IV) dimers adsorbed onto clay with the ability to catalyze water oxidation were also reported.[45]

2.7. Pyclen and Isocyclam Mn(III,IV) dimers

After the initial burst of research articles surrounding the synthesis of novel bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers, the number of articles published on these Mn(III,IV) complexes decreased during the late 1990s and onward. In 2008, a crystal structure of a pyclen bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimer [(pyclen)2MnIII,IV2O2][Cl]3 ·6H2O (9a) was deposited onto the Cambridge crystallographic database (CCDC #: 675326) by Alcock et al.[24] Pyclen is the pyridophane congener of cyclen (Figure 2). However, no reports related to the characterization of this Mn(III,IV) complex or comparison to the other previously synthesized macrocyclic bis-μ-oxo bridged manganese dimers were carried out at that time to our knowledge. Freire et al. successfully replicated the pyclen Mn(III,IV) dimer with a perchlorate counterion (9b) and were able to fully characterize and compare the complex to previously synthesized dimers.[25] The results were in line with similar complexes. For example, UV-vis studies in aqueous solution provided absorption bands at 382, 555, 665, and 800 nm. There were no strong indications of water oxidation activity with 9b. However, the complex was shown to be a competent catalyst for the disproportionation of H2O2, being more active than 7 in head-to-head studies.

In 2012, Tomczyk et al. reported the synthesis of two novel manganese complexes with the macrocycle isocyclam, one was a bis-μ-oxo bridged dinuclear complex and one was a Mn(III) mononuclear complex.[26] This is one of only two reports where the synthesis of both a Mn(III) mononuclear complex and a Mn(III,IV) dinuclear complex with the same ligands were described within the same study.

One of the aims of the report by Tomczyk et al. was to investigate whether a macrocyclic ligand (isocyclam) with lower symmetry than cyclam could form similar dinuclear complexes. They were able to synthesize an Mn(III,IV) dinuclear complex, [(isocyclam)2MnIII,IV2O2][ClO4]3 ·2H2O (10), by adding a solution of Mn(ClO4)2 ·6H2O in ethanol dropwise to a solution of isocyclam. The mixture was stirred and left open to air for several days resulting in dark green crystals of complex 10. UV-vis of complex 10 in water exhibited absorption bands at 548, 562, and 652 nm. The absorbance band at 548 nm was attributed to the d-d transition of a Mn(III) ion within a mixed-valence complex. In addition, the absorbance band at 562 nm corresponded to the d-d transition of the Mn(IV) ion, and the absorbance band at 652 nm was a characteristic feature of a LMCT from oxo!Mn(IV) (as previously assigned by others).[15h,26] A broad absorption band of low energy was observed in the visible and near IR range and assigned as an intervalence transfer between the Mn(III) and Mn(IV) ions, which set this compound as a Robin and Day class II. The IR spectrum of complex 10 exhibited a strong Mn2O2 vibration at 684 nm 1.[26] Cyclic voltammetry measurements of complex 10 revealed two quasi-reversible redox couples at E1/2 =0.29 and 1.09 V vs. NHE. Although both were somewhat ill-defined, the couples were assigned as MnIII,IV/MnIII,III and MnIII,IV/MnIV,IV, respectively.[26] These values are slightly more negative compared to the redox couples of previously synthesized Mn(III,IV) cyclam dimers, which may indicate that complex 10 is easier to oxidize than complexes with cyclam.

3. Mononuclear Mn(III) complexes

The biomimetic complexes synthesized with macrocyclic ligands and Mn(II) are numerous in the chemical literature.[9b,46] These monomeric Mn(II) complexes can be used to model the structure and function of SOD. However, Mn(III) macrocyclic complexes are much less prevalent, particularly as mononuclear complexes. The complexes tend to disproportionate to the thermodynamically stable dimers Mn2O2 species upon oxidation of manganese to higher valencies.[47] This thermodynamic sink often limits the potential to isolate stable monomeric coordination complexes with high valent manganese, especially in aqueous media.[47a] Of those few reported, several of these complexes were designed to mimic the OEC within PSII. Before details about the connectivity of the OEC were well-understood, it was clear that high valent manganese in the (III) and (IV) oxidation states was present within the activity of the OEC, which inspired the synthesis and designed of several mononuclear Mn(III) tetraaza macrocyclic complexes.[8,47b,48] In addition to the pursuit of biomimetic structures, these Mn(III) complexes were found to be useful in catalytic oxidation reactions.[48] The success observed with cyclam derivatives in the past toward oxidation catalysis motivated the synthesis of several Mn(III) complexes with this ligand.

The complexes covered in this section are mainly comprised of the tetraaza macrocyclic ligands: cyclal, cyclam, and cyclen as the backbone, but derivatives of this ligands are also common. Although many other types of nitrogen-containing ligands exist, these ligands were the most pertinent to the Mn(III) complexes and are the focus of this review. Table 8 contains a list of all the monomeric Mn(III) complexes described in this section. Figure 7 and Figure 8 show the ligand structures and their corresponding Mn(III) complexes, respectively. Table 9 lists all the features derived from UV/Vis spectroscopy data. Table 10 shows information regarding the electrochemical behavior of the Mn(III) complexes, while Figure 9 shows this information organized from more positive potentials to more negative potentials.

Table 8.

Mn(III) monomeric complexes with various tetraaza macrocyclic ligands.

| Coordinating Ligand | Metal Complex | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 11a | meso-5,5,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet a) | [MnIII(tet a)CI2][PF6] | |

| ]11b | meso-5,5,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet a) | [MnIII(tet a)CI2][BF4] | |

| 11c | meso-5,5,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet a) | [MnIII(tet a)Br2][PF6] | [48] |

| 11 d | meso-5,5,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet a) | [MnIII(tet a)(NCS)2][NCS] | |

| 11 e | meso-5,5,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet a) | [MnIII(tet a)CI2][Cl]·3H2O | |

| 11f | meso-5,5,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet a) | [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][Cl]·1.5H2O | [47b] |

| 12a | rac-5,7,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet b) | [MnIII(tet b)Cl2][PF6] | [49] |

| 12b | rac-5,7,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet b) | [MnIII(tet b)Br2][PF6] | |

| 12c | rac-5,7,7,12,12,14-hexamethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (tet b) | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2[Cl]·4H2O | [47b] |

| 13a | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl] | [50] |

| 13b | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)Br2][Br] | [50,51] |

| 13c | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(NCS)2][NCS] | |

| 13d | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(N3)2][ClO4] | [50] |

| 13e | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)Br2][PF6] | [52] |

| 13f | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)CI2][BF4] | |

| 13g | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][CF3SO3] | [47b] |

| 13h | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(NO3)2][NO3] | [51] |

| 13 i | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][NO3] | |

| 13j | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)CI2][Cl]·5H2O | [8,51] |

| 13k | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(CN)2][CIO4] | [51] |

| 13 l [a] | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)Br2][Br]·H2O | |

| 13m [a] | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl]·0.33CH3OH | [8] |

| 13n | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(OH2)2][CF3SO3)3·H2O | |

| 13o | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)I2][I] | |

| 13p | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(ONO)2][ClO4] | [53] |

| 13q | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(OClO3)2][ClO4] | |

| 13 r | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(CH3COO)(CH3COOH)][ClO4]2 | |

| 13s | 1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (cyclam) | [MnIII(cyclam)(N3)2[CF3SO3] | |

| 14a | 1,4,8,12-tetraazacylcotetradecane (cyclal) | [MnIII(cyclal)Br2][PF6] | [52] |

| 14b | 1,4,8,12-tetraazacylcotetradecane (cyclal) | [MnIII(cyclal)Cl2][Cl]·H2O | [54] |

| 15a | 5-imidazole-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (imcyclam) | [MnIII(imcyclam)(ClO4)][ClO4]2 | [55] |

| 15b | 5-imidazole-1,4,8,11-tetraazacyclotetradecane (imcyclam) | [MnIII(imcyclam)Cl][ClO4]2 | |

| 16 | 1,4,7,11-tetrazacyclotetradecane (isocyclam) | [MnIII(isocyclam)Cl2][Cl]·2H2O | [26] |

| 19 [a] | 1,4,7,10-tetraaza-2,6-pyridinophane (pyclen) | [MnIII(pyclen)Cl2][ClO4] | [25] |

| 20a [a] | 4,11-dimethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazabicyclo[6.6.2]hexadecane (etcyclam) | [MnIII(etcyclam)Cl2][PF6] | |

| 20b [a] | 4,11-dimethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazabicyclo[6.6.2]hexadecane (etcyclam) | [MnIII(etcyclam)(N3)2][PF6] | |

| 20c [a] | 4,11-dimethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazabicyclo[6.6.2]hexadecane (etcyclam) | [MnIII(etcyclam)(OH)(OAc)][PF6] | [47a] |

| 20d [a] | 4,11-dimethyl-1,4,8,11-tetraazabicyclo[6.6.2]hexadecane (etcyclam) | [MnIII(etcyclam)(OMe)2][PF6] | |

| 21 [a] | 4,10-dimethyl-1,4,7,10-tetraazabicyclo[5.5.2]tetradecane (etcyclen) | [MnIII(etcyclen)Cl2][PF6] | |

Indicates complex is in the cis-geometry, all others are in the trans-geometry.

Figure 7.

Tetraaza macrocyclic ligands described in Table 8.

Figure 8.

Structures of Mn(III) monomeric complexes with various tetraaza macrocyclic ligands.

Table 9.

Electronic spectra of selected Mn(III) complexes.

| Complex | λmax (nm),(ε, Mol −1 cm −1) | Solvent | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 11a | [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][PF6] | 917 (19), 415 sh, 377 sh, 321 sh, 279 (9500) | CH3CN | |

| 11c | [MnIII(tet a)Br2][PF6] | 855 (15), 431 sh, 370 sh, 325 sh, 291 (7800) | CH3CN | [48] |

| 12a | [MnIII(tet b)Cl2][PF6] | 917 (9), 415 sh, 377 sh, 321 sh, 277 (10,200) | MeCN | [49] |

| 12b | [MnIII(tet b)Br2][PF6] | 855 (17), 431 sh, 370 sh, 370 sh, 325 sh, 287 (10,300) | MeCN | |

| 14b | [MnIII(cyclal)Cl2][Cl]·H2O | 388 (210), 304 (920) | H2O | [54] |

| 15a | [MnIII(imcyclam)(CIO4)][ClO4]2 | 268(7860), 350 (sh, 1600) | H2O | [55] |

| 20 a | cis-[MnIII(etcyclam)Cl2][PF6] | 220(7230), 297(7670), 534(540) | CH3CN | |

| 20 b | cis-[MnIII(etcydam)(N3)2][PF6] | 227(8600), 321(8310), 433(3570), 625(170) | MeCN | |

| 20 c | cis-MnIII(etcyclam)(OH)(OAc)][PF6] | 231(9640), 409(110), 478(sh, 80) | MeCN | [47a] |

| 20 d | cis-[MnIII(etcyclam)(OMe)2][PF6] | 252(9140), 324(sh, 2600), 464(170) | MeCN | |

| 21 | cis-[MnIII(etcyclen)Cl2][PF6] | 219(4790), 294(4070), 530(190) | CH3CN | |

| 19 | cis-[MnIII(pyclen)Cl2][ClO4] | 370(sh, 153), 525(46) | CH3CN | [25] |

| 18 | [MnIIILPr(NCS)2] 0.5H2O | 315 (10884), 478 (5093), 550 (1472), 872 (309) | CH3CN | [56] |

Table 10.

Cyclic Voltammetry of Mn(III) complexes.

| Complex | MnIIIMnII E1/2 (V) vs. NHE | Solvent and Electrolyte | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| 11a | [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][PF6] | 0.45[a] | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NClO4 | [48] |

| 11c | [MnIII(tet a)Br2][PF6] | 0.62[a] | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NClO4 | |

| 11f | [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][Cl]·1.5H2O | 0.32 | H2O, 0.1 M NaClO4 | |

| 13 g | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][CF3SO3] | 0.10 | H2O, 0.1 M NaClO4 | [47b] |

| 13j | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl]·5H2O | 0.16 | DMSO, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | |

| 13 m | [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl]·0.33CH3OH | 0.56 | DMSO, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | [8,51] |

| 15a | [MnIII(imcyclam)(ClO4)][ClO4]2 | 0.33 | H2O, 0.1 M NaClO4 | [8] |

| 20a | cis-[MnIII(etcyclam)Cl2][PF6] | 0.59[b] | CH3CN„ 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | |

| 20b | cis-[MnIII(etcyclam)(N3)2][PF6] | 0.28[b] | CH3CN„ 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | |

| 20c | cis-[MnIII(etcyclam)(OH)(OAc)][PF6] | −0.68[b] | CH3CN„ 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | [47a] |

| 20d | cis-[MnIII(etcyclam)(OMe)2][PF6] | −0.78[b] | CH3CN„ 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | |

| 21 | cis-[MnIII(etcyclen)Cl2][PF6] | 0.40[b] | CH3CN, 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 | |

E1/2 was calculated from Epc and ΔE values.

Ref85 also reports a MnIV/III for 20a (1.34 V), 20 b (1.01 V), 20c (0.505 V), 20d (0.542 V), and 21 (1.177 V).

Figure 9.

Mn(III)/Mn(II) E1/2 values for the respective Mn(III) complexes.

Cyclal, cyclam, and cyclen metalate in the same fashion (through 4 nitrogen atoms contained in the backbone), but the different cavity size of the 15- vs. 14- vs. 12-membered rings, respectively, bring about slightly different characteristics for each metal complex. Typically, cyclal and cyclam coordinate the metals in a planar/trans fashion because the macrocyclic cavities are large enough to accommodate metal ions. In contrast, cyclen coordinates to metals in a folded/cis fashion, because the macrocyclic cavity is not quite large enough to completely encase the entire metal ion.

Examples of the first Mn(III) monomeric complexes with cyclam were reported in the mid-1970s.[48,49] Initially, these complexes were investigated to show how manipulation of the cyclam backbone brought about different properties to each Mn(III) complex. In each monomeric complex derived from a macrocyclic scaffold, the molecule included additional conformational preferences or steric bulk postulated to favor the monomeric Mn(III) systems over μ-oxo dimers described in Mn(III) complexes described herein include addition of methyl groups onto the C- or N-atoms of the macrocycle core, ethylene cross-bridges between N-atoms, macrocycle ring size (14), and incorporation of pyridine moieties. A trans configuration that resists dimer formation is preferred when macrocycles with ring size 14 atoms are bound to Mn(III). In the remainder of ligands, the steric bulk built into the scaffold sufficiently blocks the formation of the Mn dimers

3.1. Sterically bulky ligands

Bryan et al. published reports on several Mn(III) complexes with hexamethyl cyclam derivatives: tet a and tet b (Figure 8).[47b,48,49] [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][PF6] (11a), [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][BF4] (11b), [MnIII(tet a)Br2][PF6] (11c), [MnIII(tet a)(NCS)2][NCS] (11d), [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][Cl]·3H2O (11e), [MnIII(tet b)Cl2][PF6] (12a), and [MnIII(tet b)Br2][PF6] (12b) were all synthesized in a similar manner.[49] Each ligand was metalated with Mn(II) and subsequently reacted with an oxidizing agent such as NOPF6 or NOBF4 to obtain the desired Mn(III) complexes (11a–e and 12a–b). In addition to the original Mn(III) complexes reported as PF6 or BF4 salts, Bryan et al. also conducted metathesis reactions to obtain corresponding NCS, Cl, and Br salts. Each complex was six-coordinated with Mn(III) through the four nitrogen atoms from the ligand and two trans axial ligands (which vary depending on the synthetic route), giving the complex an octahedral geometry. The manganese cation within the complexes was bound to the ligand in a planar fashion and created two six-membered chelate rings and two five-membered chelate rings (5–6-5–6 coordination). The six-membered rings adopted a chair confirmation and the two five-membered chelate rings adopted two different enantiomeric conformations, λ and α.[48,49] It was noted that these Mn(III) complexes could withstand larger pH changes compared to the Mn(II) counterparts.[48,49]

Following the synthesis of the Mn(III) complexes with hexamethyl cyclam derivatives, Mn(III) mononuclear complexes with cyclam were reported by Chan et al. in 1976.[50] In their report, Chan et al. stated that because of the excess methyl substitutions present in the complexes synthesized previously by Bryan et al., there were concerns with steric effects.[50] Therefore, the authors synthesized mononuclear Mn(III) complexes with the unsubstituted and unsaturated cyclam ligand, forming complexes [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl] (13a), [MnIII(cyclam)Br2][Br] (13b), [MnIII(cyclam)(NCS)2][NCS] (13c), and [MnIII(cyclam)(N3)2[ClO4] (13d). Complexes 13a–13d were obtained by bubbling air through solutions containing equimolar amounts of ligand and metal salt. The magnetic moments (μeff) of samples derived from these methods indicated that Mn(III) was high spin within the cyclam complexes.[50]

3.2. Ring size ≥14atoms

Additional Mn(III) complexes with cyclam and cyclal have also been reported.[52,54] The metallation procedures followed similar methods for metalation as in previous reports; equimolar amounts of ligand and metal salt were combined with an oxidizing agent (i.e. bromine or chlorine) to obtain the Mn(III) complexes, [MnIII(cyclam)Br2][PF6] (13e), [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][BF4] (13f), and [MnIII(cyclal)Br2][PF6] (14a) and [MnIII-(cyclal)Cl2][Cl]·H2O (14b). The absorption spectra of each Mn(III) complex was obtained in acetonitrile, water and/or the solid state. Based on these spectral results and previous work by Busch et al., the authors concluded that the 14-membered cyclam ligand provided a better match of cavity size for the Mn(III) radius than the 15-membered cyclal ligand.[52,57]

It wasn’t until 1987 that a crystal structure of a Mn(III) hexamethyl cyclam complex ([MnIII(tet a)Cl2][Cl]·1.5H2O (11f) was published by Hambley et al.[47b] Three different complexes were described: [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][CF3SO3] (13g), [MnIII(tet a)Cl2][Cl]·1.5H2O (11f), and [Mn(tet b)Cl2][Cl]·4H2O (12c). The crystal structure of 11f indicated that the geometry of the Mn(III) was closed to octahedral, with the tet a ligand coordinated to four equatorial N-atom sites and two chloride ions coordinated in trans axial sites. The five-membered chelate rings adopted skewed conformations and the six-membered chelate rings adopted distorted chair geometries, similar to a previously reported complex by Bryan et al.[48,49] The observed Mn N (2.074 Å and 2.043 Å) and Mn Cl (2.549 Å) bond distances in 11f were shorter than those reported for nonmacrocyclic ligand complexes to date.[47b,58] Each complex exhibited a MnIII/MnII couple at a broad range of potentials (13g E1/2 =0.087 V vs. NHE; 11f E1/2 =0.317 V vs. NHE).[47b] This result reflects the significant impact that ligand size and substitution can have on the redox chemistry of a metal complex.

Mn(III) derivatized cyclam complexes were produced for comparison to Mn(III) porphyrin complexes as catalysts for olefin epoxidation reactions. Kimura et al. evaluated the impact of incorporating a proximal imidazole donor for activation. Mn(III) complexes were studied for cyclam and Imcylam, a cyclam modified with an imidazole moiety on one of the C-atoms of the propylene groups (Figure 7).[55] For this study, two different imidazole-modified Mn(III) cyclam complexes were synthesized, [MnIII(imcyclam)(ClO4)][ClO4]2 (15a) and [MnIII(imcyclam)Cl][ClO4]2 (15b).[55] The electronic spectra of complex 15a with a LMCT band at 268 nm and a d-d band at 350 nm in water was consistent with other reported Mn(III) complexes in tetragonally distorted environments.[55] Conversely, the Mn(III) cation was coordinated in a square planar fashion by the cyclam ligand with the proximal imidazole and chloride ion bound in axial positions. The difference between Mn Nimidazole axial (2.277 Å) and Mn N equatorial (2.06 Å) bond lengths is consistent with Jahn-Teller distortions for a high-spin d4 Mn(III) ion. Cyclic voltammetry measurements of complex 15a at scan rates of 500 mV/s showed a quasi-reversible redox event (E1/2 = 0.33 V vs. NHE) corresponding to MnIII/MnII couple.[55] The addition of the proximal imidazole onto the cyclam complex increased the catalytic epoxidation turnover, similar to porphyrins previously tested.[55,59]

In the same year Daugherty et al. synthesized seven new cyclam Mn(III) mononuclear complexes, with a variety of axial ligands and counterions: [MnIII(cyclam)Br2][Br] (13b), [MnIII(cyclam)(NCS)2][NCS] (13c), [MnIII(cyclam)(NO3)2][NO3] (13h), [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][NO3] (13i), [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl]·5H2O (13j), [MnIII(cyclam)(CN)2][ClO4] (13k), and [MnIII(cyclam)Br2][Br]·H2O (13l).[51] All but one of the complexes were isolated in the trans configuration. Cis-[MnIII(cyclam)Br2][Br]·H2O (13l) was produced by adding a small amount of HBr to the previously reported/ synthesized dimeric compound [(cyclam)2MnIII,IV2O2]Br3 ·5H2O (6b).[20] When HBr was added to the green, dinuclear complex crystals, and immediate change to dark red was observed. Unfortunately, complex 13l was unstable in all solvents.[51] The solid state structures for complexes 13b, 13c, 13h, and 13i exhibited roughly trans octahedral geometry around each Mn(III) center. The magnetic properties of all the complexes, except one, were consistent with high-spin d4 Mn(III) ions. Complex 13k, which contained two trans-cyano groups coordinated to Mn(III), had magnetic properties consist with a lowspin d4 Mn(III) ion.

Létumier et al. published a detailed report on the cis-trans isomerization of two Mn(III) mononuclear cyclam complexes in 1998.[8] Although there had already been many reports on trans-cyclam Mn(III) complexes, cis-cyclam Mn(III) complexes were relatively rare in the chemical literature. A one-pot synthesis was used to obtain both the trans and cis isomer complexes. First, MnCl2 was added to a solution of cyclam in methanol, solvent evaporated to one-fourth volume, and filtered. The precipitate collected was identified as the trans-Mn(III) complex [MnIII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl]·5H2O (13j). The filtrate contained the bis-μ-oxo bridged Mn(III,IV) dimer complex [(cyclam)2MnIII,IV2O2]3+ (6). Concentrated HCl was added to this olive green, dinuclear Mn(III,IV) complex mixture to give the cis-Mn(III) complex [MnII(cyclam)Cl2][Cl]·0.33CH3OH (13m) as a red precipitate. Létumier et al. also observed that the cis complex was converted irreversibly to the trans-Mn(III) complex upon dissolution in aqueous media. Although there were numerous attempts to grow crystalline material of complex 13m, only the crystal structure of complex 13j was reported. Mn N and Mn Cl bond distances were similar to those reported previously in the literature.[47b,51,55] Cyclic voltammetry measurements for the cis–trans isomers were carried out; the 13m trans-MnIII/trans-MnII complex showed an irreversible reduction. Only after the complex was reduced to Mn(II) did another redox wave appear, which corresponded to the reversible oxidation of a cis-Mn(II) complex (cis-MnII/cis-MnIII).

Mossin et al. reported six additional trans-Mn(III) complexes [MnIII(cyclam)(OH2)2][CF3SO3]3 ·H2O (13n), [MnIII(cyclam)I2][I] (13o), [MnIII(cyclam)(ONO)2][ClO4] (13p), [MnIII-(cyclam)(OClO3)2][ClO4] (13q), [MnIII-(cyclam)(CH3COO)(CH3COOH)][ClO4]2 (13r), and [MnIII-(cyclam)(N3)2][CF3SO3] (13s). Crystal structures were obtained for five out of the six complexes (13n–r). All five of the complexes were high spin and in the trans configuration, which is the most energetically favorable conformation for cyclam metal complexes.[53] Axial bond distances of Mn Xax (X=O, I) differed widely, depending on the attached ion (OH2, I−, ONO−, OClO3−, CH3COO−, or CH3COOH). In contrast, the Mn−Neq bond distances were relatively similar between all the complexes, 2.03±0.01 Å.

As previously discussed in the earlier section covering Mn(III,IV) dinuclear complexes, Tomczyk et al. reported the synthesis of two novel manganese complexes with the macrocycle isocyclam (Figure 7), in 2012, one was a bis-μ-oxo bridged dinuclear complex and one was a Mn(III) mononuclear complex. In this section, the Mn(III) mononuclear complex will be discussed. Tomczyk et al. synthesized trans-[MnIII-(isocyclam)Cl2][Cl]·2H2O (16) by addition of MnCl2 ·4H2O in ethanol, to a solution of isocyclam. Upon complete addition of the metal salt and after stirring for 1.5 h, concentrated HCl was added to the solution; this resulted in a red solid which quickly turned into a clear green precipitate (complex 16). The authors theorized that the red precipitate was a cis-[MnIII-(isocyclam)Cl2][Cl] complex, but unfortunately this unstable complex only persisted in solution for about 30 s before it was converted to stable trans-[MnIII(isocyclam)Cl2][Cl]·2H2O (16). UVvisible spectroscopy was utilized to confirm the presence of a Mn(III) mononuclear complex. In aqueous solution, three absorbance bands were observed at 274, 382, and 696 nm. The absorbance bands at 382 and 696 nm validated the trans nature of the complex and correspond to the d-d transitions of Mn(III) in a weak ligand field. The absorbance band at 274 nm, which had a higher molar absorptivity, was evidence of a LMCT from the nitrogen donors of the ligand to Mn(III). It is interesting to note that the molar absorptivity of the d-d transitions observed for complex 16 were slightly higher compared to other cyclam complexes (13g); this is caused by the lower symmetry of the isocyclam complex versus the cyclam complexes.

Tetramido TAML ligands are well established and have been explored as an efficient scaffold to access mononuclear iron(V) and manganese(V) complexes.[60] In a recent report by Karmalker et al., the TAML-H4 ligand was complexed with Mn(III) to produce Li(CH3OH)2[Mn(III)(TAML)(CH3OH)] (17).[61] Unfortunately, the complex was not isolated and fully characterized but we report it here to show that the Mn(III) precursor can be used to access Mn-oxo type species that serves as a strong oxidant, capable of activating C H bonds of hydrocarbons through hydrogen atom transfers.

The LEt and LPr ligands are a part of a series of tetraaza macrocycles with strong steric constraint.[56] While the LEt congener was shown to form Mn(II)LEt(NCS)(H2O) and a [Mn-(IV)2LEt2(O)2](ClO4)2 ·3DMF dimer, no Mn(III)-O Mn(IV) was reported. Conversely a Mn(III) monomer, [Mn(III)LPr(NCS)2]·0.5H2O (18) was isolated and characterized. X-ray diffraction studies of 18 show that the monoanionic tetradentate macrocyclic ligand coordinates through the 4-nitrogen atoms to the equatorial plane of the manganese(III) ion.[62] Two axially coordinated isothiocyanate anions are also bound trans to one another via the manganese(III) center. This complex was later shown to form a stable soluble magnet when coordinated with sodium terephthalate linkers in H2O/DMF. Coupling along the 1D coordination polymer was negligible (with Δeff/kB=13.7(5) K and τ0 =1.4(5) ×10 −7 s), thus validating that this is indeed a single molecule magnet. This is an interesting and very distinct application of Mn(III) complexes compared to the typical catalytic reactivities described in this review.

Work with pyridinophane macrocycles, defined here as a macrocycle that includes a pyridine ring in the chelating core, is lagging compared to the more prominent structures derived from cyclen and cyclam type ligands. Recently, Freire et al. reported the monomeric Mn(III) derivative of pyclen (19), which forms a cis type structure based on X-ray diffraction studies.[25] The team showed that while this complex was not a water oxidation catalyst, it did show moderate activity as a catalase mimic for the disproportionation of H2O2. Thanks to spectrophotometric studies of the catalytic process, it was determined that the corresponding μ-oxo dimer (10) played an active role in the catalytic cycle. When compared to work from the Lee et al., which has also shown Mn(II) Py2N2 type complexes are also capable of this type of reactivity, it can be assumed that the higher oxidation state is responsible for the observed catalase type reactivity.[46a,h]

3.3. Cross-bridged macrocycles

Hubin et al. reported crystal structures for cis-Mn(III) mononuclear complexes of etcyclam and etcyclen (Figure 7).[47a] These complexes were the first crystal structures of cis-Mn(III) monomeric macrocyclic complexes in the literature. They were synthesized utilizing ethylene cross-bridged macrocycles with the intent to form kinetically stable, mononuclear metal complexes in high valent states. Initial attempts to synthesize Mn(III) complexes in aprotic or protic solvents with hydrated metal salts were unsuccessful; therefore, anhydrous Mn(II) complexes with the ligands, Mn(etcyclam)Cl2 and Mn(etcyclen)Cl2 were produced first. These Mn(II) complexes were then combined in methanol with NH4PF6 or Br2 as an oxidizing agent to yield complexes [MnIII(etcyclam)Cl2][PF6] (20a) and [MnIII(etcyclen)Cl2[PF6] (21). Metathesis reactions were also used to also produce complex [MnIII(etcyclam)(N3)2][PF6] (20b) and additional steps were used to obtain complexes [MnIII(etcyclam)(OH)(OAc)][PF6] (20c) and [MnIII(etcyclam)(OMe)2][PF6] (20d).