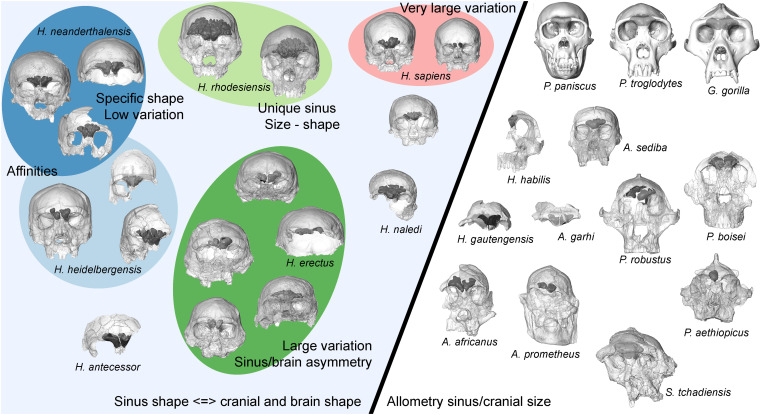

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram summarizing variation among taxa and evolutionary changes in hominin frontal sinus morphology.

The diagonal line divides taxa that seem to show different constraints on sinus morphology (specimens are not shown to scale; they are globally organized chronologically from base to top). Weak constraint on sinus development from surrounding anatomical structures and large frontal superstructures providing potential space for expansion give the sinuses the opportunity to develop isometrically with endocranial size (Fig. 3) in genera Pan, Gorilla, Sahelanthropus, Australopithecus, and Paranthropus (see right). In later hominins (see left), integration between the cranium, brain, and sinuses appears to influence sinuses expansion. Within later Homo, characteristics of sinus morphology are indicated by different colored ellipses (color code corresponds to that used inFigs. 3 to 5). Our results support the existence of separate groups within Middle Pleistocene hominins. On the basis of the frontal sinuses, there appears to be an evolutionary relationship between H. neanderthalensis and one group, which may be called H. heidelbergensis, while the group containing Broken Hill 1, and so reasonably called H. rhodesiensis, has a unique morphology that supports a distinct status. Covariation between the size and shape of the sinuses on both sides and the underlying frontal lobes has existed since at least H. erectus and was present among subsequent hominin species.