Abstract

Phase transitions in two-dimensional (2D) materials promise reversible modulation of material physical and chemical properties in a wide range of applications. 2D van der Waals layered In2Se3 with bistable out-of-plane ferroelectric (FE) α phase and antiferroelectric (AFE) β′ phase is particularly attractive for its electronic applications. However, reversible phase transition in 2D In2Se3 remains challenging. Here, we introduce two factors, dimension (thickness) and strain, which can effectively modulate the phases of 2D In2Se3. We achieve reversible AFE and out-of-plane FE phase transition in 2D In2Se3 by delicate strain control inside a transmission electron microscope. In addition, the polarizations in 2D FE In2Se3 can also be manipulated in situ at the nanometer-sized contacts, rendering remarkable memristive behavior. Our in situ transmission electron microscopy (TEM) work paves a previously unidentified way for manipulating the correlated FE phases and highlights the great potentials of 2D ferroelectrics for nanoelectromechanical and memory device applications.

A set of phase and polarization modulations are achieved in 2D In2Se3 by in situ transmission electron microscopy.

INTRODUCTION

Controlling the phases of matter is a central task for materials science. By means of phase engineering, improved performances (1–3) and extended functionalities (4) have been achieved in bulk materials. In recent years, with the exciting discovery and development of two-dimensional (2D) materials (5–8), numerous new phases were unveiled in 2D, because of their reduced dimension (9, 10). Phase transition in 2D has been frequently found in many 2D polymorphic materials (11–13). For example, by modulating the 1T′ and 2H phases in 2D MoTe2 with an optical laser, better electrical contacts can be rendered (11). On the basis of the electrically stimulated phase transition, resistive memory can be made in 2D MoTe2 (14), PdSe2 (15), TaS2 (16), etc., showing great potential for next-generation digital memory and neuromorphic computing (17, 18). The prevailed 2H-1T and 2H-1T′ phase transitions in 2D transition metal dichalcogenides can also be triggered by alkali metal intercalation, which is beneficial for the electrocatalytic performances of these materials (19). Structural phase transitions aside, arising from the reduced dimension, a variety of new physical characteristics emerged in 2D materials, such as ferroelectrics (20, 21), ferromagnetics (22, 23), superconductivity (24, 25), etc., which correlate with the phase transition in 2D materials, are currently under intensive study.

Recently, 2D van der Waals (vdW) layered In2Se3 has attracted much attention because of its multiferroic nature, e.g., ferroelectricity and ferroelasticity, in different phases (21, 26, 27). α-In2Se3 is a ferroelectric (FE) phase with out-of-plane ferroelectricity (21, 28), while β′-In2Se3 was reported as an in-plane FE phase with thickness down to 45 nm (27) and recently has been confirmed as antiferroelectric (AFE) phase (26). As a result of the bistable coexistence of AFE β′ phase and out-of-plane α phase in 2D In2Se3, it is hopeful to use this AFE and out-of-plane FE phase transition for potential applications such as next-generation transistor and nonvolatile logic devices (29). Experimentally, it has been reported that the 2D α-In2Se3 can transform into β′-In2Se3 by increasing the temperature from room temperature to 220°C (26) or 290°C (30); however, β′-In2Se3 cannot return to α-In2Se3 when the temperature drops back to room temperature, showing the difficulty in controlling the phases of 2D In2Se3 solely by the thermal effect. In addition, electric field can induce the reversible phase transition between β′ phase and the nonlayered γ phase in In2Se3 for memristor applications (31). On the theory side, density functional theory (DFT) calculations have predicted the phase transition in monolayer (one quintuple layer) α-In2Se3, namely, the strain triggered topological phase transition in 1L α-In2Se3 (32). Despite these efforts above, a complete and reversible phase transition in 2D In2Se3 still largely remains unclear, especially the reversible phase transition between FE α phase and β′ phase of interest has not been achieved.

Here, using chemical vapor deposition (CVD)–synthesized 2D β′-In2Se3, we reveal thickness-dependent phase stability in few-layer samples. When the number of 2D β′-In2Se3 layers decreases below four, the β′-In2Se3 spontaneously transforms into α-In2Se3. In addition, temperature is the conventionally dominated mode to control phase transition in bulk In2Se3. With the rising temperature, α, β, and γ bulk phase sequentially dominates in In2Se3 (33, 34), while in their 2D counterparts, AFE β′-In2Se3 emerges and competes with the out-of-plane FE α phase at the room temperature. As we present here, the phase stability of α and β′ phases in 2D In2Se3 can be controlled by strain or thickness in addition to temperature, and these previously undefined paths for phase control offer rich opportunities in 2D ferroelectrics. We apply comprehensive in situ TEM on 2D In2Se3 and confirm the phase manipulations through mechanical and electrical stimuli (scheme shown in Fig. 1A). The reversible FE phase transition between α-In2Se3 and β′-In2Se3 is first-time reported, enabled by strain manipulation. Moreover, through the local joule-heating effect, phase transition from α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3 and γ-In2Se3 can be realized. We further show that the intrinsic polarizations can be readily controlled by external electric field in 2D FE phases. These results offer a versatile platform for manipulating and engineering the phases and polarizations in 2D FE materials, which will promote the development of 2D FE devices.

Fig. 1. Phase evolutions and thickness dependence of 2D In2Se3.

(A) Atomic scheme of the phase transitions in 2D In2Se3. (B) Phase diagram of α-In2Se3 and β′- In2Se3 on strain and layer number, obtained by DFT calculations. (C) Polarized-light OM image at the polarizer azimuth angle φ = 70° presenting the typical gradient morphology of β′-In2Se3. (D) HAADF image of the edge of the β′-In2Se3. (E) The SAED patterns corresponding to the 2L-5L In2Se3, respectively. The superspots (red circles) of In2Se3 disappear for layer number less than four. (F) Atomic HAADF image and corresponding image simulation results of few-layer β′-In2Se3. (G) HAADF image and corresponding image simulation results of 1L α-In2Se3. (H) Intensity line profile corresponding to the line in (G). Atomic differential phase contrast image of (I) β′-In2Se3 phase and (J) α-In2Se3, respectively. The yellow arrows indicate the intrinsics polarization directions in AFE β′-In2Se3. Scale bars, 50 μm (C), 2 μm (D), 2 1/nm in (E), 1 nm (F and G), and 2 nm (I and J), respectively.

RESULTS

Thickness dependence of phases in 2D In2Se3

We synthesized the β′-In2Se3 single crystals using the CVD method (see Materials and Methods and fig. S1). The crystal structure of the β′-In2Se3 is shown in Fig. 1A. Because of the spontaneous polarization of the center Se atoms, few-layer β′-In2Se3 was reported with AFE structures (26). We examine the phase stability as a function of layer number and the biaxial strain using DFT calculations (see Materials and Methods; Fig. 1B). The result shows that α and β′ phases indeed have very close energies, with the ground state of α phase slightly lower than that of β′ phase, and β′ phase overwhelms α phase under tensile strain, irrespective of thickness. However, we experimentally observed different favorable phases changing with thickness. The typical optical microscope (OM) image of β′-In2Se3 with a regular triangle shape and bright-field TEM (BF-TEM) image with apparent stripe-like domain structures can be seen in fig. S2 (A and B). The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns with superspots corresponding to the periodic AFE supercell and the Raman spectrum presented in fig. S2 (B and C) also show the characteristics of β′ phase.

The wedge-shape edges of synthesized β′-In2Se3 flakes are particularly interesting. The polarized-light OM image (Fig. 1C) shows domain structures in thicker β′-In2Se3. As thickness decreases, the contrast of domains gradually vanishes. To attain better contrast, scanning TEM (STEM) with the high-angle annual dark-field (HAADF) technique is used to identify the number of layers at the edge of the β′-In2Se3, shown in Fig. 1D and fig. S3 (A and B), and the corresponding SAED patterns shown in Fig. 1E. The STEM-HAADF intensity ratio is linearly correlated with the number of layers at the edges (see Materials and Methods).

We find that when the number of layers is equal to or more than four, In2Se3 remains β′ phase with superspots in SAED (marked by red circles). On the contrary, when the number of layers is less than four, the superspots in the SAED pattern disappear, showing the phase transition from β′-In2Se3 to α-In2Se3 (Fig. 1E and fig. S3, C to E). Atomic-resolution STEM-HAADF images of 5L and 1L In2Se3 are shown in Fig. 1 (F and G, respectively), reconciling the phase identification results above. The results of atomic force microscope (AFM) and corresponding Raman spectra also prove the thickness dependence of phases in In2Se3 (fig. S4) and during the transfer process from mica to polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) and TEM grid, no phase transition occurs (fig. S5). Apparent atomic structures with bright and dark contrast are observed in 5L In2Se3, which is believed to be β′-In2Se3 (Fig. 1F). 1L In2Se3 area is verified in α phase, which is shown by the projected atomic positions of In + Se, In, and Se + Se (Fig. 1G), and the relevant intensity line profile is presented in Fig. 1H. The atomic structure and the corresponding STEM-HAADF image simulation (see Materials and Methods) results of 1L β′-In2Se3 and β-In2Se3 are shown in fig. S6 with projected atomic positions of In + Se, In + Se, and Se, which is distinct from our experimental images of 1L area. The STEM–differential phase contrast (DPC) images show the electric polarization fields (see Materials and Methods). The DPC image with periodic contrast in Fig. 1I indicates strong in-plane electric polarization field in AFE β′-In2Se3; the net in-plane polarization observed in β′-In2Se3 may imply that it has ferrielectric property resulted from the competition between FE and AFE orders (35). The net polarization direction is indexed by the yellow arrow. Compared with the β′-In2Se3, because of the weaker in-plane electric polarization field, the DPC result of α-In2Se3 presents darker contrast in Fig. 1J.

These results indicate that the AFE β′-In2Se3 is thickness dependent and likely becomes less stable than α-In2Se3 in ultrathin 2D layers (<4L). This evolution of stability with thickness is probably caused by the strain. For the thick sample, there should be still residual tensile strain in the sample after cooling from high temperature, which maintains the thick samples in β′ phase, while for thinner samples, the strain is liable to relaxation and trigger the β′-α phase transition during the CVD cooling/transfer process. Because of the smaller bending rigidity of thin (<4 layer) samples, they are prone to out-of-plane curling, buckling and wrinkling, and edge delamination (36), which can lead to local delamination from the substrates (pristine growth substrate, PMMA substrate during transfer, or Si, TEM grid, and others after transfer); as a result, we can only observe the most stable nonstrained α phase in 2D In2Se3. In contrast, the thick layers are more rigid with notably larger bending rigidity, so these thicker (>4 layer) 2D In2Se3 samples are not easy to delaminate from substrates, and they could maintain the original tensile strain state and maintain the β′ phase. The TEM-measured in-plane lattice parameters of monolayer α phase and β′ phase can also justify the residual tensile strain in β′ phase (fig. S7). Detailed strain effect on the phase transition of 2D In2Se3 is unveiled by in situ TEM and discussed in the next section.

Strain-induced reversible phase transition in 2D In2Se3

Implied by our DFT results (Fig. 1B), strain can also effectively modulate the phase transition in 2D In2Se3. As shown in Fig. 2A, we use in situ TEM techniques to load/unload the mechanical strain on our 2D samples. By using a piezo-driven nanomanipulator (see Materials and Methods), the nano-sized tungsten (W) tip applies the stress with subnanometer displacement precision. Dark-field TEM (DF-TEM) is carried out to characterize the domain structures in β′-In2Se3. Before in situ manipulation, the β′-In2Se3 shows typical nanodomain structures and superspots in the SAED pattern corresponding to the AFE phase (Fig. 2B). The W tip is then compressed downward (along z direction) approximately along the viewing direction of TEM. During compression, the β′-In2Se3 remains unchanged with intact domain structures shown in Fig. 2 (C and D). After compression by ca. 5.55 nm, the W tip is pulled back in reverse direction. As shown in Fig. 2 (E to H), the transition from β′-In2Se3 to α-In2Se3 occurs in this reverse process. In this process, the phase transition front (α/β′ interface) was determined by the contrast of nanodomains in DF-TEM. More details of the phase transition process are recorded in fig. S8 and movie S1. Comparing the TEM morphology before and after in situ experiment (figs. S9 to S12), the originally flat sample morphology apparently turns wrinkled and rippled. The corresponding SAED patterns in Fig. 2H and the postmortem Raman spectrum on the same position of the manipulated TEM sample (fig. S12C) confirm the α phase formation after an in situ compression-relaxation process.

Fig. 2. In situ βʹ-In2Se3 to α-In2Se3 phase transition.

(A) Schematic illustration of the in situ TEM setup. (B) Typical DF-TEM image of β′-In2Se3 and corresponding SAED pattern at the moment when the W tip contacts the sample. The diffraction spot selected by objective aperture for dark field was indicated by the yellow circle at the right top of (B). (C to G) Sequential TEM image series during the in situ compression and relaxation by the W tip. Initially, the sample was entirely β′-In2Se3 with obvious stripe-like domain structures in (B) to (D). After compression, when the W tip is reversely pulled back, the β′-In2Se3 starts to transform into α-In2Se3 and the domain structures gradually disappeared in (E) to (G). (H) DF-TEM image and corresponding SAED pattern of the resulted α-In2Se3 after in situ loading-unloading. Scale bars, 1 μm. (I) Schematic graphs of the in situ TEM compression-relaxation process of β′-In2Se3–to–α-In2Se3 phase transition. (J to L) The DFT calculation results of the strain-dependent energy evolution for different In2Se3 phases. Scale bars, 1 μm (B); (D) to (H) have the same scale bar as (B). Scale bars of SAED pattern in (B) and (H) are both 2 1/nm.

In addition, the in situ BF-TEM experiments for smaller and larger areas in 2D In2Se3 clearly manifest the morphology transformation during the compression-relaxation process (figs. S9 to S11 and movies S2 to S4). Before phase transition, the β′-In2Se3 on substrate (a-carbon in TEM grid) is smooth without noticeable contrast variation (figs. S9A and S11A), implying the ultraflat condition and firm attachment with the substrate. However, during the phase transition from β′-In2Se3 to α-In2Se3 (pull-back of W tip), obvious wrinkles and ripples with additional TEM contrast occur in α-In2Se3 (figs. S9, D to F, and S11, B to F). The roughened, rippled, or wrinkled morphologies in the 2D In2Se3 after such mechanical loading-unloading process are further verified by the equal inclination fringe analysis (figs. S13 and S14).

Hence, a schematic graph of the above in situ TEM phase modulation process is shown in Fig. 2I. Originally, β′-In2Se3 is stretched and fixed by the underlying substrate—amorphous carbon (a-carbon) and suffers biaxial tensile strain, which is normally caused by the cooling stress during CVD growth (36). The strain tends to be maintained during the PMMA transfer process for TEM sample preparation (see Materials and Methods and fig. S5). Upon the in situ TEM manipulation, when the W tip moves away from the β′-In2Se3, the delamination between β′-In2Se3 and the substrate (a-carbon) occurs with strain relaxation in β′-In2Se3. This mechanical delamination is partially enhanced by the differences in flexural modulus and elastic modulus of β′-In2Se3 and a-carbon substrate. In this way, the tensile strain originally restored in β′-In2Se3 applied by the substrate is released, which results in the phase transition from β′-In2Se3 to α-In2Se3. The lattice parameter of original β′-In2Se3 is larger than the relaxed α-In2Se3 (fig. S15), which further proves the strain relaxation in the compression-relaxation phase transition process. After the strain relaxation, the β′-In2Se3 film (1185.7 μm2) almost entirely transforms into α-In2Se3 (fig. S12). We also transfer the β′-In2Se3 film from mica to rough Cu substrate (fig. S16). Compared with transferred 2D film from mica to TEM grid, rough Cu substrate cannot attach with 2D In2Se3 well and cannot maintain the strain therein. The formation of ripples in 2D samples on rough Cu surface (fig. S16C) also indicates the delamination and strain relaxation, which corroborates with the in situ TEM results that after phase transition from β′-In2Se3 to α phase, many wrinkles are formed in the film because of the delamination process.

To further rationalize the strain effect on the phase stability in 2D In2Se3, we performed DFT calculations on β′-In2Se3 and α-In2Se3 under biaxial strain. As shown in Fig. 2 (J to L), the relationship between lattice constant (lattice strain) and energy for α-In2Se3 and β′-In2Se3 can be identified. The calculated in-equilibrium lattice constants (a) for α-In2Se3 and β′-In2Se3 are very close, 4.181 and 4.177 Å for 1L α-In2Se3 and β′-In2Se3, respectively. Without the external strain, the energy of α-In2Se3 is slightly lower than β′-In2Se3 regardless of the thickness. With the increasing of strain, the energy difference between β′-In2Se3 and α-In2Se3 is reduced, with interceptions at ca. 5 to 8% strain. According to thermodynamics and our DFT results, the α-β′ phase transition occurs and the mixed-phase state exists with the biaxial strain ranging from 5.55% (monolayer), 6.37% (four layer), to 7.11% (six layer), determined by the tangential line [black lines in Fig. 2 (J to L)] of the two equation-of-state curves (see Materials and Methods). Therefore, our experiments and DFT results confirm the critical role of the tensile strain on the phase control in 2D In2Se3. In addition, Raman spectroscopy (fig. S17) was used to determine the strain level during the transfer process, similar as MoS2 (37, 38). Compared with the significant shift of A1g1 peak of β′-In2Se3 on the TEM grid hole where a certain degree of strain has been released, little shift of A1g1 peak of β′-In2Se3 on mica, PMMA, and SiO2 substrates proved that the strain can be maintained during the PMMA transfer process.

Apart from the tensile strain relaxation that induces phase transition from β′-In2Se3 to α-In2Se3, α-In2Se3 is expected to transform back into β′-In2Se3 when tensile strain is applied. The scheme for this in situ TEM tensile experiment is shown in Fig. 3A. The 2D α-In2Se3 sample (on TEM grid) obtained via the above strain relaxation approach is firmly coupled with a Cu tablet, and then the entire TEM grid with a 2D sample on it can be stretched with the elongated Cu tablets mounted on an in situ TEM tensile holder (see Materials and Methods). As shown in Fig. 3 (B to I), BF-TEM is used to record the in situ tensile process. Before the start, α-In2Se3 is observed with many wrinkles. The SAED pattern without superspots in the top right of Fig. 3B confirms the absence of β′ phase. During the tensile process, with the increase in tensile distance of Cu tablet labeled on the top left of Fig. 3 (B to H), no phase changes are observed in α-In2Se3 at first. Until the tensile distance increases from 310 to 323 μm, numerous β′-In2Se3 domains suddenly appear and superspots emerge in the SAED pattern, in agreement with the phase transition from α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3 after the tensile strain reached the critical point. The recorded in situ TEM process is shown in movie S5. During the tensile process, some superspots appear in the SAED patterns of the α-In2Se3, which is induced by appearance of ordered structure during in situ tension experiment (fig. S18). It is worth noting that the β′-In2Se3 in Fig. 3H has less wrinkles or ripples than the initial α-In2Se3. Although the tensile distance is completely released to zero (back to starting point), the 2D In2Se3 still maintains the β′ phase (Fig. 3I) because of the irrecoverable plastic deformation in Cu chips and TEM grid. The scheme of the above transformation process from α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3 is presented in Fig. 3J. Meanwhile, according to the strain relaxation and in situ tension, a complete reversible process (β′-In2Se3 → α-In2Se3 → β′-In2Se3) has also been achieved on the same 2D flake sample (fig. S19).

Fig. 3. In situ α-In2Se3–to–βʹ-In2Se3 phase transition.

(A) Schematic illustration of the setup of the in situ TEM tensile experiment. (B to I) Sequential BF-TEM images during the tension and relaxation process. The uniaxial tensile direction is indicated by the yellow arrow in (B). Initially, the sample is entirely α-In2Se3 with wrinkles/ripples in (B) to (G). When the tensile distance reaches 323 μm, the α-In2Se3 transforms into β′-In2Se3 with striped domain structures (pink arrows) in (H). (I) TEM image and corresponding SAED pattern of the β′-In2Se3 after the entire in situ loading-unloading. (J) Scheme of the tensile strain induced phase transition from α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3. (K and L) The high-resolution HAADF images and corresponding simulation images of α phase and β′ phase during in situ process above. (M and N) The high-resolution HAADF image of the α/β′ interface and the corresponding GPA results. Scale bars, 1 μm (B to I) and 1 nm (K to M). Scale bars of SAED patterns in (B) to (I) are same as the scale bar of 2 1/nm in (B).

In addition, the atomic-resolution STEM-HAADF images of the α-In2Se3 and β′-In2Se3 during phase transition (Fig. 3, K and L) are matched with the multislice STEM image simulation results shown as insets of Fig. 3 (K and L). The atomic-resolution HAADF image and the corresponding strain distribution in different phases acquired at the α/β′ interface by geometric phase analysis (GPA) method (see Materials and Methods) are presented in Fig. 3 (M and N), respectively. Considerable relative tensile strain can be observed on the β′-In2Se3 side, and relative compressive strain (still in tensile range with respect to equilibrium state) on the α-In2Se3 side, in line with the DFT results. In this way, via strain manipulations, reversible phase transition between AFE β′-In2Se3 and out-of-plane FE α-In2Se3 can be readily achieved. Meanwhile, guided by the unraveled strain relaxation concept and phase transition application on other 2D materials (11, 14), FE field-effect transistors (FE-FETs) realized by phase transition are designed and FE memory performance of β′-In2Se3 and α-In2Se3 FE-FET are tested (figs. S20 and S21 and Materials and Methods), which shows promising performance.

Phase modulation in 2D In2Se3 enabled by in situ electrical TEM

Electrical stimuli influence materials through the electric field and the thermal effect (joule heating) (39). Here, we explore the phase transitions in 2D In2Se3 triggered by electrical stimuli using in situ TEM. We find that α-In2Se3 can transform into β′-In2Se3 and further γ-In2Se3, by the applied bias/current. The scheme of our in situ electrical TEM setup is shown in Fig. 4A. The bias/current is applied/measured by Keithley 2400 connected to the piezo nanomanipulator described above (see Materials and Methods). Our results show that through intensive electrical current (see Materials and Methods), the heat generated triggers the phase transition in 2D α-In2Se3. As shown in Fig. 4B, when relatively low current is applied, the phase transition from α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3 occurs. While the electrical current is relatively higher, the direct α-In2Se3–to–γ-In2Se3 transition occurs. In literature, the transition temperatures for these two transitions are 200°C (30, 40) and 520°C (41), respectively.

Fig. 4. In situ electrically stimulated α-In2Se3 to β’-In2Se3, and γ-In2Se3 phase transitions.

(A) Schematic illustration of the in situ electrical TEM setup. (B) Schematic graphs of the α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3 and γ-In2Se3 phase transitions under electrical stimuli. (C to E) Sequential TEM images when applying low current; α-In2Se3 transformed to β′-In2Se3 affected by electrical field and joule heat. (F) Temperature distribution after applying low current. (G to I) Sequential TEM images when applying high current; α-In2Se3 transforms into γ-In2Se3 (inner) and β′-In2Se3 (outer). (J) Temperature distribution after applying high current. Scale bars, 1 μm (C to E and G to I). Scale bars of SAED patterns in (C), (E), (G), and (I) are same as the scale bar 2 1/nm in (C).

The in situ electrical TEM processes are detailed in Fig. 4 (C to J). Figure 4 (C to E) shows the transition from α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3 at a relatively low current. Before the start, the SAED pattern in Fig. 4C confirms the α phase. After applying current, superspots appear in the SAED pattern (Fig. 4E), indicating the transition to β′-In2Se3 (movie S6). The corresponding I-V cycle is shown in fig. S22. The phase transition current for this case is ca. 5 × 10−5 A. Figure 4F shows the calculated temperature distribution (see Materials and Methods) for the current of 5 × 10−5 A. On the basis of the reported critical transition temperature (200°C) from α-In2Se3 to β′-In2Se3, we can estimate the radius of new β′-In2Se3 area by joule heating mechanism. The radius of the new phase area is calculated as 5.77 μm (Fig. 4F), perfectly matching with our experimental results of 5.6 μm (fig. S22 and table S1). Next, when we apply higher current (8 × 10−5 A) on the α phase (Fig. 4, G to I, and fig. S23), the temperature in the center of the contact area significantly increases. Correspondingly, the 2D In2Se3 transforms from α phase (Fig. 4G) to γ phase, as shown in Fig. 4I (movie S7), confirmed by the SAED patterns before and after in situ electrical stimuli. To better distinguish different phases, the relationship between the atomic structure and SAED patterns (both experiment and simulation) of α, β′, and γ phases are presented in fig. S24. In addition, to exclude the chemical changes induced by thermal energy generated during the above process, we also measure the element distribution before and after in situ TEM using energy-dispersive spectrum (EDS), which shows the unchanged atomic ratio 2:3 for In and Se (fig. S23B). The complete phase changes in the entire 2D In2Se3 film under high current (8 × 10−5 A) are also shown in fig. S23.

Polarization modulation in 2D In2Se3 via in situ electrical TEM

Under the direct effect of electric field, the FE polarization can be tuned in 2D In2Se3 as well. Different from the joule heating discussed in the previous section, here, we apply continuous and milder bias/current using the in situ electrical TEM technique. First, with point-like contact, the I-V curves at different phases of 2D In2Se3 can be measured (Fig. 5A). The results show that while all the contacts are governed by the Schottky barriers (42), α-In2Se3 and β′-In2Se3 have better conductivity compared with γ-In2Se3. Next, as we applied cycled bias on different phases, they show different characteristics. After several I-V cycles for electroforming (fig. S25, A and B), resistive hysteresis characteristics can be seen in α-In2Se3 (Fig. 5C); however, no resistive memory effect is observed in β′-In2Se3 and γ-In2Se3 (fig. S26, C and D).

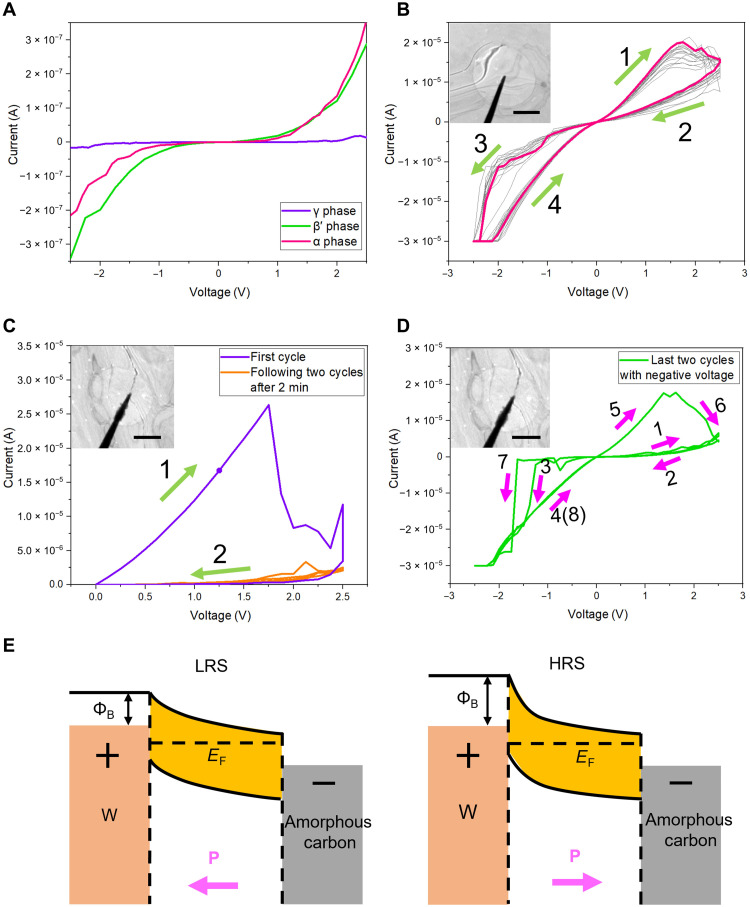

Fig. 5. Electric polarization modulation and memoristive effects in 2D In2Se3.

(A) The I-V curve for the different 2D In2Se3 phases. (B) I-V cyclic curve for α-In2Se3. Green arrows indicate the switching directions. (C) Resistive switching characteristics of the α-In2Se3 at positive bias. After the first cycle, the resistive switching disappears for the following I-V cycles. (D) Resistive switching characteristics recover after applying negative bias on the α-In2Se3 after processes shown in (C). The top-left corner images of (B) to (D) are corresponding BF-TEM images of the contact made by W tip with 2D In2Se3. Scale bars, 500 nm. (E) Schematic band diagrams for the FE polarization modulation and effects on the Schottky barrier height. LRS, low-resistance state; HRS, high-resistance state.

Further experiments are carried out to understand such resistive memory mechanism in α-In2Se3. As shown in Fig. 5C, during the first I-V cycle in positive bias, the α-In2Se3 experiences a reset process at 1.75 V. However, when we run the second and third cycles at positive voltage after 2 min, the resistive memory effect disappears, meaning that the α-In2Se3 still maintains the reset situation. Such behavior confirms that the α-In2Se3 has the potential for nonvolatile memory applications (43, 44). Meanwhile, on the same α-In2Se3 sample, when we apply I-V cycles with negative bias, the set process is completed at −1.35 V in the first cycle, and in the following cycle, obvious resistive memory effect is recovered under positive bias (Fig. 5D).

The morphology of samples and structure changes during the above I-V cycle are shown in fig. S26 and movie S8. The morphology of α-In2Se3 does not have apparent change, and the corresponding SAED patterns before and after the I-V cycle all indicate that the 2D sample maintains α-In2Se3 structure, which suggests that the memristive behavior is not due to the phase transition. In fig. S27, the HAADF-STEM image does not show contrast of defects emerging in α-In2Se3 after 15 cycles. Therefore, the conductivity changes are most likely attributed to the FE polarization in 2D α-In2Se3, explainable by the shift of Schottky barrier height under positive and negative biases (Fig. 5E). When the polarization is in the direction (negative bias) of the external electrical field, depletion region is formed and lower barrier height with low-resistance state is rendered. With the increasing of positive bias, the intrinsic polarization of α-In2Se3 will switch to the opposite z direction. In this case, more electrons are accumulated at the W/α-In2Se3 interface and result in higher Schottky barrier height and high-resistance state. Thus, the polarization in α-In2Se3 manipulated by the external electric field can successfully control the current and conductance of the channel with nonvolatile memory effects.

DISCUSSION

In summary, we report the thickness, strain, and electrically controlled phase and polarization modulation in CVD-synthesized 2D In2Se3. There is a critical layer thickness above which the α phase tends to transform into β′ phase. According to our in situ TEM results, the strain-induced reversible phase transition from β′-In2Se3 to α-In2Se3 has been confirmed. In addition, the in situ electrical TEM reveals the joule heat–modulated phases of α-, β′-, and γ-In2Se3. Last, the reversible nonvolatile resistive switching is achieved in FE α-In2Se3. These results provide new valuable insights into the phase manipulations in 2D materials and can potentially stimulate new applications in nanoelectromechanical systems and memory devices for the 2D FE materials and their phase hybrids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Synthesis of 2D β′-In2Se3

2D β′-In2Se3 films were grown on mica substrates at 800° to 850°C for 10 to 15 min under a flow of 50–standard cubic centimeter per minute argon using In2Se3 powder as precursor by atmospheric-pressure CVD. The detailed CVD and cooling process is presented in fig. S1.

(S)TEM specimen preparation

By the PMMA-assisted technique, the CVD-grown In2Se3 was transferred onto a TEM grid. First, thin-layer PMMA was spin-coated on the as-grown mica substrate at 500 rpm for 10 s and then 3000 rpm for 60 s. After heating at 100°C for 5 min, another thin-layer PMMA was spin-coated again on the as-grown mica substrate at 500 rpm for 10s and then 1000 rpm for 30 s. With the PMMA, the In2Se3 detached from the substrate by immersing in deionized water at room temperature for 10 min. Next, the PMMA/In2Se3 layer was transferred onto a TEM grid and dried at 50°C. Last, acetone was used to wipe off the PMMA.

Determination of sample thickness

The ability of electron scattering is determined by the composition elements and thickness of the sample. When the composition elements for the materials are the same, the relationship between intensity I and object thickness t can be described as (45)

| (1) |

where I0 is the intensity of the beam as it enters the object and μ is defined as the attenuation coefficient and equals the inverse of the mean free path between scattering events. The equation can be simplified as follow by Taylor series

| (2) |

In addition, when the thickness is less than 10 nm, the relationship between intensity I and object thickness t is nearly linear (45).

In situ TEM

In situ observation of the phase transition of In2Se3 was performed with JEOL 2100F. The in situ compression-relaxation experiment and electrical measurements were carried out by a nanofactory in situ holder with a pizeo-controlled tungsten tip. The pizeo-controlled tungsten tip can provide accurate compression depth to contact different samples (maximum, ±14 μm; minimum step, 2 pm). The electrical measurements were done on the Keithley 2400, which is controlled by the LabVIEW program. The in situ tension experiment in transmission electron microscope was achieved by Gatan 654 single tilt straining holder. The quantifoil TEM grid with relaxed α-In2Se3 is stuck in the Cu tablet, which enable the simultaneous deformation between Cu tablet and α-In2Se3.

STEM characterization and EDS analysis

The atomic-scale HAADF-STEM images of different In2Se3 phases were obtained by the JEM-ARM200F TEM with the cold field emission gun and the Corrected Electron Optical Systems probe spherical aberration corrector and an operated accelerating voltage of 200 kV. The vacuum during the measurement was kept at 7.7 × 10−7 mbar, and the electron beam current was 13.3 μA. For image acquisition, the camera length on STEM was 120 mm. With a defocus of 5 nm, the acquisition time of HAADF images is 19 μs per pixel. Wiener filtering was applied on HAADF-STEM images for reduction of noises. Elemental results of different In2Se3 phase were obtained from JEOL 2100F with an energy-dispersive x-ray spectrometer operated at 200 kV. Atomic-resolution DPC-STEM imaging was performed with a convergence angle of 24.4 mrad and a four-quadrant annular detector after probe aberration corrected in the Thermal-Fisher Spectra 300 TEM. The spot size was 5 and the probe current was 30 pA. The dwell time was 16 μs for DPC-STEM acquisition with the collection angle of 12 to 45 mrad and the pixel size of 0.4967 Å.

HAADF-STEM simulation

The STEM simulation is accomplished in Dr. Probe (46) by a dynamic multislice method. The parameters are set as the same as experimental imaging condition. The simulation used the DFT calculation results of β′-In2Se3 and α-In2Se3 with the accuracy of 0.01 nm/pixel.

Strain analysis on TEM image

The GPA analysis (on high-resolution HAADF-STEM image) (47) was performed with the reflexes (in reciprocal space) perpendicular to the a and b directions as the two bases, respectively.

Phase stability analysis under strain

Taking the phase-lattice constant separation using a 1D problem as an example, which is similar as the free energy versus strain (48). For a two-phase system, there are two phase regions, Lα and Lβ. Because the total extension of lattice is conserved, the overall extension of lattice constant can be described as

| (3) |

Here, the fα and fβ are the fractions of α phase and β phase. Meanwhile, aα and aβ are the extension of lattice parameter in α phase and β phase, respectively. According to the lever rule based on the Eq. 3, the fraction of two phases can be determined as follows

| (4) |

The Helmholtz free energy density of the two-phase system under isothermal-isobaric conditions can be described as

| (5) |

Here, the Fα and Fβ are Helmholtz free energy density related with the aα and aβ. Under the state of equilibrium, and and then we can deduce

| (6) |

| (7) |

Equations 6 and 7 show that the common tangent of the free energy–lattice constant curve determines the equilibrium free energy and extension of lattice parameter of mixed phases.

Transfer of α-In2Se3 films

After spin-coating PMMA and baking, the PMMA/α-In2Se3/Cu was immersed in 1 M ammonium persulfate solution for 5 hours to etch the Cu substrate, and then the PMMA/α-In2Se3 film was collected by SiO2/Si substrate and baked at 50°C for 10 min. After removing the PMMA by acetone, the α-In2Se3 film was transferred to the SiO2/Si substrate.

Device fabrication and measurement

After covering the In2Se3 films by metal hard mask, 40-nm Au was deposited to the films for contact electrodes (Denton Explorer E-beam Deposition System). The devices were tested by the semiconductor analyzer (Keithley 4200) in a probe station (Lake Shore).

Temperature field analysis

Here, we assume that the heat transfer is dominated by the In2Se3, because the thermal conductivity of a-carbon is 0.6, which is less than the thermal conductivity of 2D In2Se3 (12 to 18 W/mK), and the vacuum did not conduct heat in the TEM. In addition, steady-state heat transfer model was used to fit the temperature field induced by current. The joule heat generated by current per second can be demonstrated as follows

| (8) |

According to the steady-state heat transfer model, the 2D In2Se3 can be seen as a hollow cylinder, the inside diameter r1 can be seen as the diameter of the W tip, and the outside diameter r2 can be seen as the distance between the W tip and the Cu screen. In this way, according to the Fourier law, we can get the relationship between temperature field and rate of heat flow as follows

| (9) |

Here, Φ is the rate of heat flow, which is equal to Q, and the tr1 and tr2 are the temperature at the W tip and the Cu screen, respectively. λ is the thermal conductivity of the 2D In2Se3, and l is the thickness of the 2D In2Se3. Because the W tip is not at the center of the Cu screen, we can measure the shortest distance rS and the longest distance rL between the W tip and the Cu screen and then Eq. 9 can be modified as

| (10) |

The average distance ra can be defined as the = , and we can get the result that . In this way, we hypothesis the temperature tr2 of Cu screen is room temperature 25°C. Then, we can calculate the temperature tr1 at the contact area of the W tip and 2D In2Se3. Next, we can get the temperature field of the whole 2D In2Se3 by following equation

| (11) |

t(r) is temperature function ranges with the distance r between certain area and W tip. All the parameters have been measured as shown in table S1.

SAED pattern simulation

The SAED pattern simulation was achieved by JEMS by the Bloch wave method (49). The accelerating voltage is 200 kV, and the thickness of the sample is set as 10 nm. Other parameters are same as the JEOL 2100F TEM. The crystal structure and lattice parameters are same as our DFT results.

DFT calculation

DFT calculations were performed to achieve optimized geometrical and strain-dependent energy change using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package code (VASP.5.4.4.18) (50, 51) with the projector augmented wave (52) basis and the vdW-DF exchange-correlation functional method (53, 54). The kinetic energy cutoff was set to 350 eV. The first Brillouin zone was sampled by Γ-centered 9 × 3 × 1 k-point grids for the structural relaxation. Total energy and the force on each atom were converged to less than 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV/Å, respectively. The vacuum space of more than 15 Å along the z direction was used to minimize possible periodic interactions.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 51872248, 51922113, 52173230, and 22105162), Hong Kong Research Grant Council Collaborative Research Fund (project no. C5029-18E), Early Career Scheme (project no. 25301018), the Hong Kong Research Grant Council General Research Fund (project nos. 11312022, 11300820 and 15302419), the City University of Hong Kong (project nos. 6000758 and 9229074), The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (project nos. 1-ZVGH, ZVRP, 1-BE47, and ZE2F), and the Shenzhen Science, Technology and Innovation Commission (project no. JCYJ20200109110213442).

Author contributions: J.Z., M.Y., and T.H.L. conceived and led the project. X.Z., W.H., L.W.W., C.S.T., S.P.L., T.H.L., and J.Z. prepared the samples and conducted the sample characterizations and TEM experiments. K.Y. and M.Y conducted the DFT simulations. K.H.L. and F.Z. assisted with the TEM experiments. T.Y. conducted the AFM tests. All the authors discussed the manuscript (MS) and agreed on its contents.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S27

Table S1

References

Other Supplementary Material for this manuscript includes the following:

Movies S1 to S8

REFERENCE AND NOTES

- 1.Li Z., Pradeep K. G., Deng Y., Raabe D., Tasan C. C., Metastable high-entropy dual-phase alloys overcome the strength–ductility trade-off. Nature 534, 227–230 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He B. B., Hu B., Yen H. W., Cheng G. J., Wang Z. K., Luo H. W., Huang M. X., High dislocation density–induced large ductility in deformed and partitioned steels. Science 357, 1029–1032 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang S., Wang H., Wu Y., Liu X., Chen H., Yao M., Gault B., Ponge D., Raabe D., Hirata A., Chen M., Wang Y., Lu Z., Ultrastrong steel via minimal lattice misfit and high-density nanoprecipitation. Nature 544, 460–464 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eerenstein W., Mathur N. D., Scott J. F., Multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Nature 442, 759–765 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Novoselov K. S., Geim A. K., Morozov S. V., Jiang D., Zhang Y., Dubonos S. V., Grigorieva I. V., Firsov A. A., Electric field effect in atomically thin carbon films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Manzeli S., Ovchinnikov D., Pasquier D., Yazyev O. V., Kis A., 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17033 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gogotsi Y., Anasori B., The rise of MXenes. ACS Nano 13, 8491–8494 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hong Y.-L., Liu Z., Wang L., Zhou T., Ma W., Xu C., Feng S., Chen L., Chen M.-L., Sun D.-M., Chen X.-Q., Cheng H.-M., Ren W., Chemical vapor deposition of layered two-dimensional MoSi2N4 materials. Science 369, 670–674 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Geng X., Sun W., Wu W., Chen B., Al-Hilo A., Benamara M., Zhu H., Watanabe F., Cui J., Chen T.-p., Pure and stable metallic phase molybdenum disulfide nanosheets for hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 7, 10672 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li W., Qian X., Li J., Phase transitions in 2D materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 829–846 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho S., Kim S., Kim Jung H., Zhao J., Seok J., Keum Dong H., Baik J., Choe D.-H., Chang K. J., Suenaga K., Kim Sung W., Lee Young H., Yang H., Phase patterning for ohmic homojunction contact in MoTe2. Science 349, 625–628 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheon Y., Lim S. Y., Kim K., Cheong H., Structural phase transition and interlayer coupling in few-layer 1T′ and Td MoTe2. ACS Nano 15, 2962–2970 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Y.-C., Dumcenco D. O., Huang Y.-S., Suenaga K., Atomic mechanism of the semiconducting-to-metallic phase transition in single-layered MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 9, 391–396 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang F., Zhang H., Krylyuk S., Milligan C. A., Zhu Y., Zemlyanov D. Y., Bendersky L. A., Burton B. P., Davydov A. V., Appenzeller J., Electric-field induced structural transition in vertical MoTe2- and Mo1–xWxTe2-based resistive memories. Nat. Mater. 18, 55–61 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li Y., Loh L., Li S., Chen L., Li B., Bosman M., Ang K.-W., Anomalous resistive switching in memristors based on two-dimensional palladium diselenide using heterophase grain boundaries. Nat. Electron. 4, 348–356 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshida M., Suzuki R., Zhang Y., Nakano M., Iwasa Y., Memristive phase switching in two-dimensional 1T-TaS2 crystals. Sci. Adv. 1, e1500606 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen H., Xue X., Liu C., Fang J., Wang Z., Wang J., Zhang D. W., Hu W., Zhou P., Logic gates based on neuristors made from two-dimensional materials. Nat. Electron. 4, 399–404 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huh W., Lee D., Lee C. H., Memristors based on 2D materials as an artificial synapse for neuromorphic electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002092 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Voiry D., Yamaguchi H., Li J. W., Silva R., Alves D. C. B., Fujita T., Chen M. W., Asefa T., Shenoy V. B., Eda G., Chhowalla M., Enhanced catalytic activity in strained chemically exfoliated WS2 nanosheets for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 12, 850–855 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fei Z., Zhao W., Palomaki T. A., Sun B., Miller M. K., Zhao Z., Yan J., Xu X., Cobden D. H., Ferroelectric switching of a two-dimensional metal. Nature 560, 336–339 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng C., Yu L., Zhu L., Collins James L., Kim D., Lou Y., Xu C., Li M., Wei Z., Zhang Y., Mark T. E., Li S., Seidel J., Zhu Y., Jefferson Z. L., Tang W.-X., Michael S. F., Room temperature in-plane ferroelectricity in van der Waals In2Se3. Sci. Adv. 4, eaar7720 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bedoya-Pinto A., Ji J.-R., Avanindra K. P., Gargiani P., Valvidares M., Sessi P., Taylor James M., Radu F., Chang K., Stuart S. P. P., Intrinsic 2D-XY ferromagnetism in a van der Waals monolayer. Science 374, 616–620 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Y., Ray A., Shao Y.-T., Jiang S., Lee K., Weber D., Goldberger J. E., Watanabe K., Taniguchi T., Muller D. A., Mak K. F., Shan J., Coexisting ferromagnetic–Antiferromagnetic state in twisted bilayer CrI3. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 143–147 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Park S., Kim S. Y., Kim H. K., Kim M. J., Kim T., Kim H., Choi G. S., Won C. J., Kim S., Kim K., Talantsev E. F., Watanabe K., Taniguchi T., Cheong S.-W., Kim B. J., Yeom H. W., Kim J., Kim T.-H., Kim J. S., Superconductivity emerging from a stripe charge order in IrTe2 nanoflakes. Nat. Commun. 12, 3157 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costanzo D., Zhang H., Reddy B. A., Berger H., Morpurgo A. F., Tunnelling spectroscopy of gate-induced superconductivity in MoS2. Nat. Nanotechnol. 13, 483–488 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu C., Chen Y., Cai X., Meingast A., Guo X., Wang F., Lin Z., Lo T. W., Maunders C., Lazar S., Wang N., Lei D., Chai Y., Zhai T., Luo X., Zhu Y., Two-dimensional antiferroelectricity in nanostripe-ordered In2Se3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 047601 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xu C., Mao J., Guo X., Yan S., Chen Y., Lo T. W., Chen C., Lei D., Luo X., Hao J., Zheng C., Zhu Y., Two-dimensional ferroelasticity in van der Waals β’-In2Se3. Nat. Commun. 12, 3665 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhou Y., Wu D., Zhu Y., Cho Y., He Q., Yang X., Herrera K., Chu Z., Han Y., Downer M. C., Peng H., Lai K., Out-of-plane piezoelectricity and ferroelectricity in layered α-In2Se3 nanoflakes. Nano Lett. 17, 5508–5513 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin L. W., Rappe A. M., Thin-film ferroelectric materials and their applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16087 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tao X., Gu Y., Crystalline–Crystalline phase transformation in two-dimensional In2Se3 thin layers. Nano Lett. 13, 3501–3505 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi M. S., Cheong B.-k., Ra C. H., Lee S., Bae J.-H., Lee S., Lee G.-D., Yang C.-W., Hone J., Yoo W. J., Electrically driven reversible phase changes in layered In2Se3 crystalline film. Adv. Mater. 29, 1703568 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang X., Feng Y., Chen K.-Q., Tang L.-M., The coexistence of ferroelectricity and topological phase transition in monolayer α-In2Se3 under strain engineering. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 32, 105501 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van Landuyt J., Van Tendeloo G., Amelinckx S., Phase transitions in In2Se3 as studied by electron microscopy and electron diffraction. Physica Status Solidi (a) 30, 299–314 (1975). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye J., Soeda S., Nakamura Y., Nittono O., Crystal structures and phase transformation in In2Se3 compound semiconductor. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 37, 4264–4271 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin L.-F., Zhang Y., Moreo A., Dagotto E., Dong S., Frustrated dipole order induces noncollinear proper ferrielectricity in two dimensions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 067601 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ly T. H., Yun S. J., Thi Q. H., Zhao J., Edge delamination of monolayer transition metal dichalcogenides. ACS Nano 11, 7534–7541 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang L., Cui X., Zhang J., Wang K., Shen M., Zeng S., Dayeh S. A., Feng L., Xiang B., Lattice strain effects on the optical properties of MoS2 nanosheets. Sci. Rep. 4, 5649 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Z., Lv Y., Ren L., Li J., Kong L., Zeng Y., Tao Q., Wu R., Ma H., Zhao B., Wang D., Dang W., Chen K., Liao L., Duan X., Duan X., Liu Y., Efficient strain modulation of 2D materials via polymer encapsulation. Nat. Commun. 11, 1151 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao J., Huang J.-Q., Wei F., Zhu J., Mass transportation mechanism in electric-biased carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 10, 4309–4315 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Han G., Chen Z.-G., Drennan J., Zou J., Indium selenides: Structural characteristics, synthesis and their thermoelectric performances. Small 10, 2747–2765 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Popović S., Tonejc A., Gržeta-Plenković B., Čelustka B., Trojko R., Revised and new crystal data for indium selenides. J. Appl. Cryst. 12, 416–420 (1979). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong L.-W., Huang L., Zheng F., Thi Q. H., Zhao J., Deng Q., Ly T. H., Site-specific electrical contacts with the two-dimensional materials. Nat. Commun. 11, 3982 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cheng S., Lee M.-H., Li X., Fratino L., Tesler F., Han M.-G., Del Valle J., Dynes R. C., Rozenberg M. J., Schuller I. K., Zhu Y., Operando characterization of conductive filaments during resistive switching in Mott VO2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2013676118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ouyang J., Chu C.-W., Szmanda C. R., Ma L., Yang Y., Programmable polymer thin film and non-volatile memory device. Nat. Mater. 3, 918–922 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Van den Broek W., Rosenauer A., Goris B., Martinez G. T., Bals S., Van Aert S., Van Dyck D., Correction of non-linear thickness effects in HAADF STEM electron tomography. Ultramicroscopy 116, 8–12 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barthel J., Dr. Probe: A software for high-resolution STEM image simulation. Ultramicroscopy 193, 1–11 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hÿtch M. J., Snoeck E., Kilaas R., Quantitative measurement of displacement and strain fields from HREM micrographs. Ultramicroscopy 74, 131–146 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xue F., Li Y., Gu Y., Zhang J., Chen L.-Q., Strain phase separation: Formation of ferroelastic domain structures. Phys. Rev. B 94, 220101 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stadelmann P. A., EMS - a software package for electron diffraction analysis and HREM image simulation in materials science. Ultramicroscopy 21, 131–145 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kresse G., Furthmüller J., Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kresse G., Furthmüller J., Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Blöchl P. E., Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dion M., Rydberg H., Schröder E., Langreth D. C., Lundqvist B. I., Van der Waals density functional for general geometries. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 246401 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Román-Pérez G., Soler J. M., Efficient implementation of a van der Waals density functional: Application to double-wall carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 096102 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lewandowska R., Bacewicz R., Filipowicz J., Paszkowicz W., Raman scattering in α-In2Se3 crystals. Mater. Res. Bull. 36, 2577–2583 (2001). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S27

Table S1

References

Movies S1 to S8