Abstract

Introduction

In randomized controlled trials, add-on brivaracetam (BRV) reduced seizure frequency in patients with drug-resistant focal epilepsy. Most real-world research on BRV has focused on refractory epilepsy. The aim of this analysis was to assess the 12-month effectiveness and tolerability of adjunctive BRV when used as early or late adjunctive treatment in patients included in the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk Study (BRIVAFIRST).

Methods

BRIVAFIRST was a 12-month retrospective, multicenter study including adult patients prescribed adjunctive BRV. Effectiveness outcomes included the rates of sustained seizure response, sustained seizure freedom, and treatment discontinuation. Safety and tolerability outcomes included the rate of treatment discontinuation due to adverse events (AEs) and the incidence of AEs. Data were compared for patients treated with add-on BRV after 1–2 (early add-on) and ≥ 3 (late add-on) prior antiseizure medications.

Results

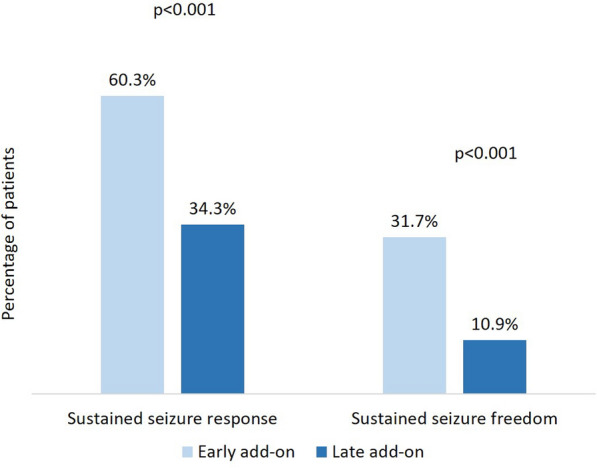

A total of 1029 patients with focal epilepsy were included in the study, of whom 176 (17.1%) received BRV as early add-on treatment. The median daily dose of BRV at 12 months was 125 (100–200) mg in the early add-on group and 200 (100–200) in the late add-on group (p < 0.001). Sustained seizure response was reached by 97/161 (60.3%) of patients in the early add-on group and 286/833 (34.3%) of patients in the late add-on group (p < 0.001). Sustained seizure freedom was achieved by 51/161 (31.7%) of patients in the early add-on group and 91/833 (10.9%) of patients in the late add-on group (p < 0.001). During the 1-year study period, 29 (16.5%) patients in the early add-on group and 241 (28.3%) in the late add-on group discontinued BRV (p = 0.001). Adverse events were reported by 38.7% and 28.5% (p = 0.017) of patients who received BRV as early and late add-on treatment, respectively.

Conclusion

Brivaracetam was effective and well tolerated both as first add-on and late adjunctive treatment in patients with focal epilepsy.

Keywords: Antiseizure medication, Brivaracetam, Focal seizures, Epilepsy

Key Summary Points

| Brivaracetam (BRV) improved seizure frequency both as first add-on and late adjunctive treatment in patients with focal epilepsy. |

| The median daily dose at 12 months was 125 mg and 200 mg in the early and late add-on groups. |

| Sustained seizure frequency reduction was greater and retention rate was higher for BRV as an early add-on treatment. |

| Adjunctive BRV was generally well tolerated in clinical practice and most adverse events were mild. |

| The most common adverse events included somnolence, nervousness and/or agitation, vertigo, and fatigue. |

Introduction

Brivaracetam (BRV) is a rationally developed compound characterized by high-affinity binding to synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) and chemical structure similar to levetiracetam (LEV) [1]. In Europe, BRV is authorized for the adjunctive treatment of focal-onset seizures, including focal to bilateral tonic–clonic seizures, in patients over 2 years of age [2].

In randomized, placebo-controlled trials, BRV reduced seizure frequency when added to pre-existing antiseizure medications (ASMs) in patients with drug-resistant focal epilepsy [3]. Most real-world research on BRV has focused on refractory epilepsy and only a few studies have provided preliminary insights about BRV use in special populations [4–6] and in the early stages of treatment [7]. There is, hence, little information about the effectiveness of BRV when it is administered as a first or second add-on therapy.

The BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk Study (BRIVAFIRST) investigated the use of adjunctive BRV in a large population of patients with focal epilepsy treated according to daily clinical practice over a 1-year period [8, 9]. BRIVAFIRST represents the largest real-world study of BRV, and the size of the cohort allows for sub-analyses to be performed.

The aim of this analysis was to explore the effectiveness and tolerability of adjunctive BRV when used as early add-on or later adjunctive treatment in patients included in BRIVAFIRST.

Methods

Participants

BRIVAFIRST was a retrospective study conducted across 62 Italian centers [8, 9]. Adult patients attending participating centers who were prescribed to BRV (March 2018–March 2020) and were on stable treatment with at least one ASM during the prior 90 days were retrospectively identified. Only patients with focal epilepsy and with 12-month follow-up after initiating BRV were included in the current analysis. Data on demographics, clinical history, type of seizures and epilepsy [10], etiology, previous/concomitant ASMs, and baseline seizure frequency (monthly seizure frequency during the 3 months before starting BRV) were collected. Patients in the early add-on group were treated with BRV as add-on therapy after one or two prior ASMs; the late add-on group consisted of patients who received BRV as add-on therapy after three or more prior ASMs.

Data on seizure occurrence, adverse events (AEs), and drug withdrawal were retrieved from patient seizures diaries and clinical records; visits at 3, 6, and 12 months were performed as standard practice when a new ASM is initiated. Exclusion criteria were history of alcoholism, drug abuse, conversion disorders, or other non-epileptic ictal events.

Effectiveness outcomes included sustained seizure response (SSR) and sustained freedom (SSF); seizure worsening (greater than 25% increase in monthly seizure frequency relative to baseline) and treatment discontinuation at 12 months were also considered. Sustained seizure response (freedom) was defined as a reduction of at least 50 (100%) in baseline seizure frequency that continued without interruption from the first time it was achieved through the 12-month follow-up without BRV withdrawal in patients with at least one seizure during the 3 months before introducing BRV; the time of achievement of SSR and SSF was established using data at visits at 3, 6, and 12 months [11].

Safety and tolerability outcomes included the rate of treatment discontinuation due to AEs and the incidence of AEs considered BRV-related by participating physicians.

Statistical Analysis

Values were presented as median [interquartile range] for continuous variables and number (percentage) of subjects for categorical variables. In this sub-analysis, demographic and baseline characteristics and study outcomes were compared between early-add on and late add-on patient groups. Comparisons were made using the Mann–Whitney test or chi-squared test, as appropriate. Simple and multivariable logistic regression models were performed to identify baseline characteristics of patients associated with SSR and SSF. Selected independent variables were age, number of concomitant ASMs, concomitant use of sodium channel blockers (SCBs), baseline monthly seizure frequency, and early add-on treatment with BRV [11, 12]. Carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, eslicarbazepine acetate, lacosamide, and rufinamide were classified as SCBs; patients in the SCB group were those receiving at least one SCB, whereas those in the no-SCB group did not take any SCB. Results were considered significant for p values less than 0.05 (two sided). Data analysis was performed using STATA/IC 13.1 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA). The study is reported according to STROBE guidelines [13].

Standard Protocol Approval

BRIVAFIRST was approved by the ethics committee at any participating site and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation in the study, informed consent (e.g., explanation of the purposes of the research, information about handling of personal data and results of the research, description of the procedures adopted for ensuring data protection) was obtained from any patient or from one of the parents or from the legal representative.

Results

Out of 1325 patients initially identified, 71 patients were excluded as diagnosed with generalized, combined, or unknown epilepsy and 225 because follow-up after initiating BRV was less than 1 year at time of the current analysis. Accordingly, 1029 patients with focal epilepsy fulfilled the inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included, of whom 176 (17.1%) received BRV as early add-on treatment. Patients who received BRV as add-on therapy after one or two prior ASMs were older at time of epilepsy diagnosis, had a shorter duration of epilepsy, were treated with a lower number of concomitant ASMs, and had a lower seizure frequency at baseline in comparison to patients who received BRV as late add-on therapy after more than two prior ASMs. Baseline characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients

| Characteristics | Early add-on (n = 176) | Late add-on (n = 853) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 45 (30–61) | 45 (33–55) | 0.883 |

| Male sex | 85 (48.3) | 402 (47.1) | 0.778 |

| Age at epilepsy onset, years | < 0.001 | ||

| N | 176 | 852 | |

| Median | 23 (11–47) | 12 (5–22) | |

| Duration of epilepsy, years | < 0.001 | ||

| N | 176 | 852 | |

| Median | 11 (5–25) | 27 (16–39) | |

| Type of seizure | 0.832 | ||

| N | 157 | 759 | |

| Focal onset | 114 (72.6) | 565 (74.4) | |

| Focal to bilateral tonic–clonic | 32 (20.4) | 139 (18.3) | |

| Focal onset and focal to bilateral tonic–clonic | 11 (7.0) | 55 (7.3) | |

| Etiology | 0.918 | ||

| Structural | 98 (55.7) | 455 (53.3) | |

| Genetic | 6 (3.4) | 34 (4.0) | |

| Immune | 1 (0.6) | 10 (1.2) | |

| Infectious | 2 (2.3) | 24 (2.8) | |

| Unknown | 67 (38.1) | 330 (38.7) | |

| Number of previous ASMs | < 0.001 | ||

| N | 176 | 847 | |

| Median | 2 (1–2) | 7 (4–9) | |

| Number of concomitant ASMs | 1 (1–2) | 2 (2–3) | < 0.001 |

| Concomitant use of SCB(s) at baseline | < 0.001 | ||

| N | 166 | 735 | |

| Patients | 128 (77.1) | 643 (87.5) | |

| aseline monthly seizure frequencya | 3 (1–6) | 7 (3–20) | < 0.001 |

Data are median (IQR) for continuous variables, and n (%) for categorical variables

ASM antiseizure medications, IQR interquartile range, SCB sodium channel blocker, N total number of patients for whom data in question were available

aBased on the number of seizures during the 90 days before starting adjunctive BRV

The median daily dose of BRV at 3 months was 100 (100–150) in the early add-on group and 100 (100–200) in the late add-on group (p = 0.087); it was 100 (100–150) mg in the early add-on group and 150 (100–200) in the late add-on group (p < 0.001) at 6 months, and it was 125 (100–200) mg in the early add-on group and 200 (100–200) in the late add-on group (p < 0.001) at 12 months.

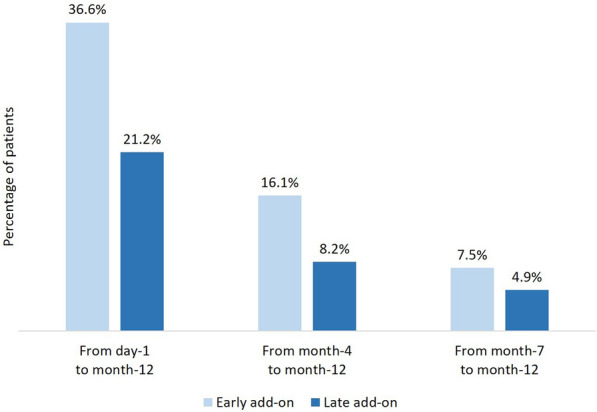

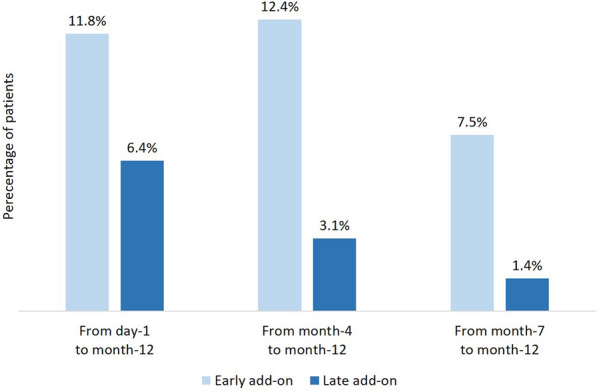

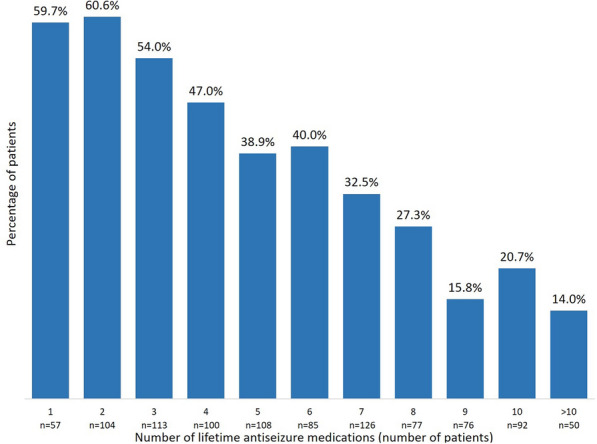

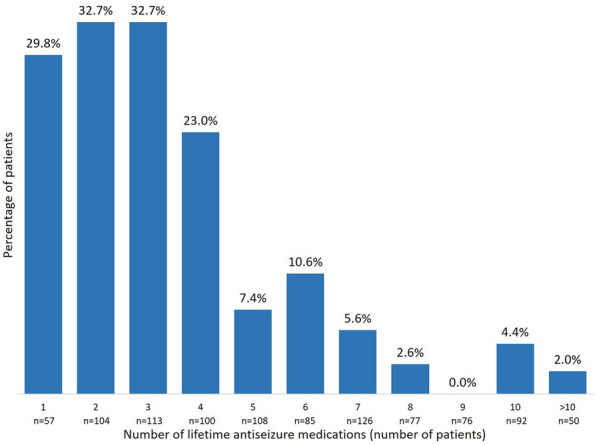

During the 1-year study period, SSR was reached by 97/161 (60.3%) of patients in the early add-on group and 286/833 (34.3%) of patients in the late add-on group (p < 0.001); SSF was achieved by 51/161 (31.7%) of patients in the early add-on group and 91/833 (10.9%) of patients in the late add-on group (p < 0.001) (Fig. 1). Among patients who received BRV as early add-on treatment, 59 (36.6%) were sustained seizure responders from day 1, 26 (16.1%) from month 4, and 12 (7.5%) from month 7; in the late add-on group, SSR was reached by 177 (21.2%) patients from day 1, 68 (8.2%) patients from month 4, and 41 (4.9%) patients from month 7 (Fig. 2). In the early add-on group, 19 (11.8%) patients achieved SSF from day 1, 20 (12.4%) from month 4, and 12 (7.5%) from month 7; among patients who received BRV as late add-on treatment, 53 (6.4%) were seizure free from day 1, 26 (3.1%) from month 4, and 12 (1.4%) from month 7 (Fig. 3). The overall rates of SSR and SSF according to the number of prior ASMs are illustrated in Figs. 4 and 5.

Fig. 1.

Sustained seizure response and sustained seizure freedom with brivaracetam according to early-add on treatment

Fig. 2.

Time to sustained seizure response with brivaracetam according to early-add on treatment

Fig. 3.

Time to sustained seizure freedom with brivaracetam according to early-add on treatment

Fig. 4.

Sustained seizure response according to the number of lifetime antiseizure medications

Fig. 5.

Sustained seizure freedom according to the number of lifetime antiseizure medications

Age, the number of concomitant ASMs, the concomitant use of SCBs, the baseline monthly seizure frequency, and the timing to add BRV within lifetime ASMs were independent predictors of SSR and SSF with older age, the lower number of lifetime ASMs, the concomitant administration of SCBs, the lower baseline seizure count, and the use of BRV as early add-on treatment being associated with a higher likelihood to achieve SSR (Table 2) and SSF (Table 3).

Table 2.

Association between baseline characteristics and sustained seizure response

| Dependent variable | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.02) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 0.011 |

| Number of concomitant ASMs | 0.69 (0.60–0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.75 (0.64–0.89) | 0.001 |

| Concomitant use of SCBs | 1.57 (1.03–2.39) | 0.037 | 2.05 (1.30–3.21) | 0.002 |

| Baseline monthly seizure frequency | 0.98 (0.98–0.99) | < 0.001 | 0.99 (0.98–0.99) | 0.001 |

| Brivaracetam early add-on | 2.90 (2.05–4.10) | < 0.001 | 2.13 (1.45–3.14) | 0.005 |

Values are from logistic regression models

ASM antiseizure medications, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, SCB sodium channel blocker

aAdjustment for age, number of concomitant ASMs, concomitant use of SCBs, baseline monthly seizure frequency, and treatment with brivaracetam as early add-on

Table 3.

Association between baseline characteristics and sustained seizure freedom

| Dependent variable | Unadjusted | Adjusteda | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p value | OR (95% CI) | p value | |

| Age | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (1.00–1.03) | 0.030 |

| Number of concomitant ASMs | 0.47 (0.37–0.59) | < 0.001 | 0.56 (0.43–0.75) | < 0.001 |

| Concomitant use of SCBs | 1.29 (0.71–2.33) | 0.402 | 2.02 (1.07–3.81) | 0.029 |

| Baseline monthly seizure frequency | 0.92 (0.89–0.94) | < 0.001 | 0.94 (0.91–0.97) | < 0.001 |

| Brivaracetam early add-on | 3.78 (2.54–5.62) | < 0.001 | 1.99 (1.26–3.16) | 0.003 |

Values are from logistic regression models

ASM antiseizure medications, CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio, SCB sodium channel blocker

aAdjustment for age, number of concomitant ASMs, concomitant use of SCBs, baseline monthly seizure frequency, and treatment with brivaracetam as early add-on

There were no differences in the rates of seizure worsening between the early and late add-on groups at 3-month (early add-on 2.3%, late add-on 4.8%; p = 0.134), 6-month (early add-on 3.4%, late add-on 3.1%; p = 0.802), and 12-month (early add-on 0.6%, late add-on 2.6%; p = 0.100) follow-up visits.

During the 1-year study period, 29 (16.5%) patients in the early add-on group and 241 (28.3%) in the late add-on group discontinued BRV (p = 0.001). The reasons for treatment withdrawal were insufficient efficacy [early add-on n = 16 (9.1%), late add-on n = 144 (16.9%); p = 0.009], AEs [early add-on n = 13 (7.4%), late add-on n = 90 (10.6%); p = 0.203], and a combination of both [early add-on n = 0, late add-on n = 5 (0.6%); p = 0.309]; in one case, BRV was discontinued because of the patient’s request and one patient died as a result of a cause unrelated to treatment.

Adverse events were reported by 38.7% and 28.5% (p = 0.017) of patients who received BRV as early and late add-on treatment, respectively, and they were rated as mild (75.4%), moderate (24.2%) and severe (0.4%) in intensity. The most common AEs observed in both study groups included somnolence, nervousness and/or agitation, vertigo, and fatigue (Table 4).

Table 4.

Adverse events with brivaracetam according to early add-on treatment

| Patients with adverse events | Early add-on | Late add-on |

|---|---|---|

| N | 137 | 740 |

| n (%) | 53 (38.7) | 211 (28.5) |

| Most frequently reported adverse events* | ||

| N | 136 | 716 |

| Somnolence, n (%) | 11 (8.1) | 45 (6.3) |

| Nervousness and/or agitation, n (%) | 12 (8.8) | 38 (5.3) |

| Vertigo, n (%) | 5 (3.7) | 26 (3.6) |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 8 (5.9) | 18 (2.5) |

| Headache, n (%) | 5 (3.7) | 17 (2.4) |

| Aggressiveness, n (%) | 2 (2.2) | 18 (2.5) |

| Mood change, n (%) | 5 (3.7) | 15 (2.1) |

| Dizziness, n (%) | 3 (2.2) | 16 (2.2) |

| Sleep disturbances, n (%) | 4 (2.9) | 11 (1.5) |

| Memory disturbance, n (%) | 5 (3.7) | 9 (1.3) |

| Anxiety | 2 (2.2) | 3 (0.4) |

| Nausea/vomiting | – | 8 (1.1) |

| Disturbances in attention/concentration | 3 (2.2) | 3 (0.4) |

N total number of patients for whom data in question were available

AEs reported by < 1% of patients: tremor (all n = 8), stomach pain (n = 7), diplopia/blurred vision (all n = 5), weight increase (n = 4), skin disorders, hair loss (all n = 3), fever, pharyngodynia, hyporexia (all n = 2), urinary disturbances, weight decrease, psychosis, tics, confusion, tinnitus, constipation, abdominal pain (all n = 1)

*Reported by ≥ 1% of patients in each group

Discussion

In this exploratory post hoc analysis of BRIVAFIRST data, BRV was associated with a greater sustained seizure frequency reduction measured as SSR and SSF and a higher retention rate when added as an early add-on treatment in patients with focal onset seizures than in patients receiving the drug as a late add-on therapy.

Thus far, very limited evidence in small groups of patients exists that has directly compared the effects of adjunctive BRV at different stages of epilepsy treatment. In BRIVA-LIFE, a multicenter retrospective study aimed to evaluate the use of BRV in clinical practice, patients with fewer lifetime ASMs were more likely to respond to treatment [7]. The rates of seizure freedom were 50.0% in 2 patients with a history of one ASM, 42.9% in 14 patients with a history of two ASMs, and 40.0% in 40 patients with a history of three ASMs. The seizure freedom rates progressively declined with the increased number of prior ASMs and reached 2.6% in patients who had used 12 ASMs [7]. These findings are consistent with data from other studies with different ASMs that evaluated the impact of the number of lifetime drugs and demonstrated better responses in the early add-on setting [14, 15].

In BRIVAFIRST, patients had a reduction of baseline seizure frequency also when BRV was added as a late add-on therapy and had the chance to reach the status of SSF even they had tried more than 10 medications before for epilepsy treatment. These figures indicate the efficacy of BRV to control seizures when added to the pre-existing therapeutic regimen in patients with difficult-to-treat epilepsy and matched previous real-world evidence [7, 16–23].

Importantly, the maintenance of seizure frequency reduction over time is crucial for patients with epilepsy. In this regard, it is not clear whether the short-term efficacy of an ASM observed during the treatment phase of regulatory trials is a predictor of long-term drug effects. Further, missing data of patients who discontinue the medication before the end of the treatment period are generally imputed from the last available visits to estimate the seizure freedom rate. This approach can result into the risk of inflating the drug efficacy and providing a view that is not truly representative of the actual treatment response. In addition, although 50% response rate and change in median seizure frequency are typically used to measure whether trial participants successfully respond to treatment, individual seizure rates are highly volatile, with large fluctuations from month to month that may simply reflect the natural course of the disease itself [24, 25]. In this context, sustained efficacy outcomes that exclude patients who withdrew the treatment or had only a transient reduction in seizure frequency represent more reliable and informative measures of drug efficacy and more nuanced approaches to measuring individual treatment response. In the current subgroup analysis of BRIVAFIRST, the SSR and SSF were observed in around 60% and 32% of patients when BRV was given as the first- or second add-on treatment; the corresponding figures in patients who received BRV as a later therapeutic option were 35% and 11%. Of note, sustained seizure frequency reduction was obtained on the first day of treatment in most cases, supporting the evidence that BRV can have an early, sustained onset of action, with potential utility when rapid onset of action is necessary [26, 27]. The lack of need for titration with initiation at target dose and the fast entry of BRV into the central nervous system may contribute to explain the early onset of action. The increase in the rates of SSR and SSF over time suggests that BRV efficacy can be sustained even in patients who respond later, although the shorter follow-up available for these patients needs to be acknowledged.

The concomitant use of SCBs was an independent predictor of SSR and SSF, supporting the notion that favorable combinations usually consist of ASMs with different mechanisms of action [8, 28]. Further research is warranted to confirm this preliminary evidence and explore how BRV can be better combined in clinical practice within the frame of so-called rational polypharmacy.

The burden of concomitant medications and the baseline seizure frequency can act as surrogate markers of the intrinsic disease severity, and the inverse relationship found between the response to adjunctive BRV and these baseline characteristics is consistent with prior studies [12, 29]. Likewise, age was an independent predictor of sustained seizure frequency reduction, with older age being associated with a greater likelihood to achieve SSR and SSF; the better response to BRV in older versus younger patients is also in line with prior evidence [5, 7, 30]. Remarkably, ASMs are generally found to be more efficacious in elderly than younger patients when outcomes are stratified by age, and differences across the age groups can largely be explained by differences in baseline characteristics of participants [31, 32].

Since patients with epilepsy require long-term therapy, treatment discontinuation represents an important clinical concern. During the 1-year study period, the overall rate of treatment discontinuation was about 25%, which substantially overlapped the rates found in retrospective non-interventional studies of BRV [7, 16–23] and newer ASMs in clinical practice [32–35]. Further, fewer patients in the early than in the late add-on group discontinued BRV and the difference was mainly driven by the lower rate of treatment withdrawal due to insufficient efficacy.

The differences found in effectiveness outcomes between the early and late add-on groups were not unexpected. Patients in the late add-on group had a younger age at epilepsy onset and a longer duration of epilepsy in comparison to patients in the early add-on group, who developed epilepsy later in life. Although the actual prevalence of drug resistance across the study cohort was not available, patients who received BRV as late adjunctive treatment had a higher number of lifetime and concomitant ASMs. Further, patients in the late add-on group had a higher baseline seizure frequency and received a higher dose of BRV. All these features suggest that the two groups may comprise different epilepsy subtypes and patients who received BRV as late add-on treatment had a long-standing and more difficult to treat epilepsy.

Adverse events were reported by around 30% of the patients and were generally mild to moderate in intensity. Patients who received BRV as early add-on therapy reported AEs more frequently, while there was no significant difference in the rate of treatment discontinuation due to tolerability issues in comparison to late add-on patients’ group. In this regard, early add-on patients had a lower seizure frequency at baseline and the number of seizures during the last year has been shown to be inversely associated with the likelihood to experience adverse drug effects [36]. It may be hypothesized that patients who have more frequent seizures may worry more about the disease than adverse drug effects and consider the AEs as symptoms of the epilepsy, whereas patients with better seizure control are more likely to attribute symptoms to the drugs that they are taking [36]. It is also possible that patients with a shorter disease duration and a lower number of lifetime ASMs may be more prone to report to physicians the occurrence of untoward drug effects in comparison to patients with a longer disease duration and a greater number of prior ASMs, who instead may be more usual and in a certain sense accustomed to experience AEs.

Somnolence, vertigo, and fatigue were the most frequent AEs and substantially overlap the profile of side effects of the majority of ASMs [37]; nervousness and agitation were the most common psychiatric AEs. These findings confirmed the overall favorable tolerability profile of BRV when added to concomitant ASMs irrespective of treatment stage and matched data from prior randomized and non-randomized studies [7, 16–23, 38, 39].

The main strengths of BRIVAFIRST included the recruitment at multiple sites and the large cohort of included patients, which allowed exploratory subgroup analyses. The real-world setting, which reflects the treatment approach employed by physicians according to the usual healthcare practice, can increase the external validity of the findings and the generalizability to other real-world populations with similar baseline characteristics. Further, the SSF and SSR as metrics of treatment efficacy offer insights into the clinical response to treatment from a novel perspective. Some limits need to be also acknowledged. The main limitation of the study is the lack of a control group or comparison with other therapeutic options, which prevented any definitive conclusions about the comparative efficacy and tolerability of BRV with other ASMs. The open-label and retrospective design may have introduced potential sources of bias. Further, the collection of AEs as recorded during clinical visits rather than by standardized questionnaires might have resulted in underreporting.

Conclusion

Brivaracetam was effective and well tolerated both as first add-on as well as late adjunctive treatment in patients with focal epilepsy. The best response to BRV was obtained in early-stage treatment and was associated with higher rates of sustained seizure frequency reduction and retention. Even some patients at the late stage of treatment who had received more than 10 prior ASMs could become free from seizure with the addition of BRV. Further research is warranted to explore the potential of BRV in specific etiologies and epilepsy syndromes to provide additional guidance for clinical decisions.

Acknowledgements

Angela Alicino: Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neurosciences and Sense Organs–University Hospital of Bari “A. Moro”, Michele Ascoli: Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Magna Græcia University of Catanzaro, Catanzaro, Italy, Giovanni Assenza: Dipartimento di Neurologia, Neurofisiopatologia, Neurobiologia, Università Campus Bio-Medico, Roma, Italy, Federica Avorio: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Valeria Badioni: Neurology Unit, Maggiore Hospital, ASST Lodi, Lodi, Italy, Paola Banfi: Circolo Hospital, Fondazione Macchi—ASST Settelaghi, Varese, Italy, Emanuele Bartolini: USL Central Tuscany, Neurology Unit, Nuovo Ospedale Santo Stefano, Prato, Italy, Luca Manfredi Basili: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Vincenzo Belcastro: Neurology Unit, Maggiore Hospital, ASST Lodi, Lodi, Italy, Simone Beretta: San Gerardo Hospital, ASST Monza, Italy, Irene Berto: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Martina Biggi: Department Neurology 2, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy, Giuseppe Billo: Epilepsy Center, UOC Neurology, AULSS 8 Vicenza, Vicenza, Italy, Giovanni Boero: Complex Structure of Neurology, SS Annunziata Hospital, Taranto, Italy, Paolo Bonanni: IRCCS Medea Scientific Institute, Epilepsy Unit, Conegliano, Treviso, Italy, Jole Bongorno: Neurology Unit, Giovanni Paolo II Hospital, Ragusa, Italy, Francesco Brigo: Department of Neurology, Hospital of Merano (SABES-ASDAA), Merano-Meran, Italy, Emanuele Caggia: Neurology Unit, Giovanni Paolo II Hospital, Ragusa, Italy, Claudia Cagnetti: Neurological Clinic, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, Marche Polytechnic University, Ancona, Italy, Carmen Calvello: Dipartimento di Neurologia, Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia, Università di Perugia, Perugia, Italy, Edward Cesnik: Neurology Unit, AOU Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy, Gigliola Chianale: Neurology Unit, San Giovanni Bosco Hospital, Turin, Italy, Domenico Ciampanelli: Institute of Clinical Neurophysiology, Department of Neuroscience, Policlinico Riuniti, Foggia, Italy, Roberta Ciuffini: Department of Life, Health, and Environmental Sciences, University of L’Aquila, Epilepsy Center, Ospedale San Salvatore, L’Aquila, Italy, Dario Cocito: Presidio Sanitario Major, Istituti Clinici Scientifici Maugeri, Turin, Italy, Donato Colella: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Margherita Contento: Department Neurology 2, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy, Cinzia Costa: Dipartimento di Neurologia, Ospedale Santa Maria della Misericordia, Università di Perugia, Perugia, Italy, Eduardo Cumbo: Neurodegenerative Disorders Unit, Azienda Sanitaria Provinciale di Caltanissetta, Caltanissetta, Italy, Alfredo D'Aniello: IRCCS Neuromed, Pozzilli, Italy, Francesco Deleo: Epilepsy Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta”, Milan, Italy, Jacopo C DiFrancesco: San Gerardo Hospital, ASST Monza, Italy, Roberta Di Giacomo: Epilepsy Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta”, Milan, Italy, Alessandra Di Liberto: Neurology Unit, San Giovanni Bosco Hospital, Turin, Italy, Elisabetta Domina: Neurology Unit, Maggiore Hospital, ASST Lodi, Lodi, Italy, Fedele Dono: Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinican Science, “G. D'Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Italy, Vania Durante: Neurology Unit, “Perrino” Hospital, Brindisi, Italy, Maurizio Elia: Oasi Research Institute- IRCCS, Troina, Italy, Anna Estraneo: IRCCS Fondazione Don Carlo Gnocchi, Florence, Italy, Giacomo Evangelista: Department of Neuroscience, Imaging and Clinican Science, “G. D'Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Italy, Maria Teresa Faedda: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Ylenia Failli: Department Neurology 2, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy, Elisa Fallica: Neurology Unit, AOU Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy, Jinane Fattouch: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Alessandra Ferrari: Division of Clinical Neurophysiology and Epilepsy Center, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova, Italy, Florinda Ferreri: Department of Neurosciences, University of Padua, Padua, Italy, Giacomo Fisco: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Davide Fonti: University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy, Francesco Fortunato: Dipartimento di neurologia, Università “Magna Græcia”, Catanzaro, Italy, Nicoletta Foschi: Neurological Clinic, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, Marche Polytechnic University, Ancona, Italy, Teresa Francavilla: Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Neurosciences and Sense Organs- University Hospital of Bari “A. Moro”, Rosita Galli: Neurology Unit, Department of Cardio-neuro-vascular Sciences, San Donato Hospital, Arezzo, Italy, Stefano Gazzina: Clinical Neurophysiology Unit, Epilepsy Center, Spedali Civili, Brescia, Italy, Anna Teresa Giallonardo: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Filippo Sean Giorgi: Department of Translational Research on New Technologies in Medicine and Surgery, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy, Neurology Unit, Pisa University Hospital, Pisa, Italy, Loretta Giuliano: Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences and Advanced Technologies “G.F. Ingrassia”, Section of Neurosciences, University of Catania, Catania, Italy, Francesco Habetswallner: Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Cardarelli Hospital, Naples, Italy, Francesca Izzi: Epilepsy Centre, Neurology Unit, Department of Systems Medicine, Policlinico Tor Vergata, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy, Benedetta Kassabian: Department of Neurosciences, University of Padua, Padua, Italy, Angelo Labate: Dipartimento di neurologia, Università “Magna Græcia”, Catanzaro, Italy, Concetta Luisi: Department of Neurosciences, University of Padua, Padua, Italy, Matteo Magliani: Department Neurology 2, Careggi University Hospital, Florence, Italy, Giulia Maira: Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences and Advanced Technologies “G.F. Ingrassia”, Section of Neurosciences, University of Catania, Catania, Italy, Luisa Mari: Epilepsy Centre, Neurology Unit, Department of Systems Medicine, Policlinico Tor Vergata, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy, Daniela Marino: Neurology Unit, Department of Cardio-neuro-vascular Sciences, San Donato Hospital, Arezzo, Italy, Addolorata Mascia: IRCCS Neuromed, Pozzilli, Italy, Alessandra Mazzeo: Institute of Clinical Neurophysiology, Department of Neuroscience, Policlinico Riuniti, Foggia, Italy, Stefano Meletti: Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Science, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy, Chiara Milano: Department of Translational Research on New Technologies in Medicine and Surgery, University of Pisa, Pisa, Italy, Neurology Unit, Pisa University Hospital, Pisa, Italy, Annacarmen Nilo: Clinical Neurology Department of Neurosciences University Hospital S. Maria della Misericordia, Udine, Italy, Biagio Orlando: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Francesco Paladin: Epilepsy Centre, Neurology Unit, Venice, Italy, Maria Grazia Pascarella: Neurology Unit, Maggiore Hospital, ASST Lodi, Lodi, Italy, Chiara Pastori: Epilepsy Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta”, Milan, Italy, Giada Pauletto: Neurology Unit Department of Neurosciences University Hospital S. Maria della Misericordia, Udine, Italy, Alessia Peretti: Neurological Clinic, Department of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, Marche Polytechnic University, Ancona, Italy, Epilepsy Centre, Neurology Unit, Venice, Italy, Gabriella Perri: Neurology Unit, ASST Rhodense, Milan, Italy, Marianna Pezzella: Department of Clinical Neurophysiology, Cardarelli Hospital, Naples, Italy, Marta Piccioli: Dipartimento di neurologia, Ospedale San Filippo Neri, Roma, Pietro Pignatta: Neurology and epilepsy unit Humanitas Gradenigo Hospital, Turin, Italy, Nicola Pilolli: Complex Structure of Neurology, SS Annunziata Hospital, Taranto, Italy, Francesco Pisani: Neurology Unit, Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, University of Messina, Italy, Laura Rosa Pisani: Neurology Unit, Cutroni-Zodda Hospital, Barcellona, Messina, Italy, Fabio Placidi: Epilepsy Centre, Neurology Unit, Department of Systems Medicine, Policlinico Tor Vergata, University of Rome “Tor Vergata”, Rome, Italy, Patrizia Pollicino: IRCCS Centro Neurolesi Bonino-Pulejo, Messina, Italy, Vittoria Porcella: AOU Sassari, Sassari, Italy, Silvia Pradella: Department of Epileptology, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico Carlo Besta, Milan, Italy, Epilepsy Center, Child Neuropsychiatry Unit, AAST Santi Paolo Carlo, Milan, Italy, Monica Puligheddu: University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy, Stefano Quadri: Neurology Unit, ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy, Pier Paolo Quarato: IRCCS Neuromed, Pozzilli, Italy, Rui Quintas: Epilepsy Unit, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Neurologico “Carlo Besta”, Milan, Italy, Rosaria Renna: Epilepsy Outpatient Clinic for Adults. “A. Cardarelli” Hospital, Naples, Italy., Giada Ricciardo Rizzo: Epilepsy Centre, Neurology Unit, Venice, Italy, Adriana Rum: Dipartimento di neurologia e neurofisiopatologia, Aurelia Hospital, Roma, Enrico Michele Salamone: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Ersilia Savastano: Department of Human Neurosciences, Policlinico Umberto I, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy, Maria Sessa: Neurology Unit, ASST Papa Giovanni XXIII, Bergamo, Italy, David Stokelj: Neurology Clinic, ASUGI, Trieste, Italy, Elena Tartara: Epilepsy Center, IRCCS Mondino Foundation, Pavia, Italy, Mario Tombini: Dipartimento di Neurologia, Neurofisiopatologia, Neurobiologia, Università Campus Bio-Medico, Roma, Italy, Gemma Tumminelli: Epilepsy Center, Child Neuropsychiatry Unit, AAST Santi Paolo Carlo, Milan, Italy, Anna Elisabetta Vaudano: Department of Biomedical, Metabolic and Neural Science, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy, Maria Ventura: Neurology Unit, Giovanni Paolo II Hospital, Ragusa, Italy, Ilaria Viganò: Epilepsy Center, Child Neuropsychiatry Unit, AAST Santi Paolo Carlo, Milan, Italy, Emanuela Viglietta: Neurology and epilepsy unit Humanitas Gradenigo Hospital, Turin, Italy, Aglaia Vignoli: Department of Health Sciences, Università degli Studi, Milan, Italy, Flavio Villani: Division of Clinical Neurophysiology and Epilepsy Center, IRCCS Ospedale Policlinico San Martino, Genova, Italy, Elena Zambrelli: Epilepsy Center, Child Neuropsychiatry Unit, AAST Santi Paolo Carlo, Milan, Italy, Lelia Zummo: Neurology and Stroke Unit, P.O. ARNAS-Civico, Palermo, Italy

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Simona Lattanzi designed and conceptualized the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, carried out the data analyses, and drafted the manuscript. Valentina Chiesa, Edoardo Ferlazzo, Angela La Neve, and Elisa Montalenti designed and conceptualized the study, and coordinated and supervised the data collection. Laura Canafoglia, Maria Paola Canevini, Sara Casciato, Emanuele Cerulli Irelli, Filippo Dainese, Giovanni De Maria, Giuseppe Didato, Giancarlo Di Gennaro, Giovanni Falcicchio, Martina Fanella, Massimo Gangitano, Oriano Mecarelli, Alessandra Morano, Federico Piazza, Chiara Pizzanelli, Patrizia Pulitano, Federica Ranzato, Eleonora Rosati and Laura Tassi were involved in the acquisition of data. Carlo Di Bonaventura designed and conceptualized the study, coordinated and supervised the data collection, and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

List of Investigators: BRIVAFIRST Group Membership

Angela Alicino, Michele Ascoli, Giovanni Assenza, Federica Avorio, Valeria Badioni, Paola Banfi, Emanuele Bartolini, Luca Manfredi Basili, Vincenzo Belcastro, Simone Beretta, Irene Berto, Martina Biggi, Giuseppe Billo, Giovanni Boero, Paolo Bonanni, Jole Bongiorno, Francesco Brigo, Emanuele Caggia, Claudia Cagnetti, Carmen Calvello, Edward Cesnik, Gigliola Chianale, Domenico Ciampanelli, Roberta Ciuffini, Dario Cocito, Donato Colella, Margherita Contento, Cinzia Costa, Eduardo Cumbo, Alfredo D'Aniello, Francesco Deleo, Jacopo C DiFrancesco, Roberta Di Giacomo, Alessandra Di Liberto, Elisabetta Domina, Fedele Dono, Vania Durante, Maurizio Elia, Anna Estraneo, Giacomo Evangelista, Maria Teresa Faedda, Ylenia Failli, Elisa Fallica, Jinane Fattouch, Alessandra Ferrari, Florinda Ferreri, Giacomo Fisco, Davide Fonti, Francesco Fortunato, Nicoletta Foschi, Teresa Francavilla, Rosita Galli, Stefano Gazzina, Anna Teresa Giallonardo, Filippo Sean Giorgi, Loretta Giuliano, Francesco Habetswallner, Francesca Izzi, Benedetta Kassabian, Angelo Labate, Concetta Luisi, Matteo Magliani, Giulia Maira, Luisa Mari, Daniela Marino, Addolorata Mascia, Alessandra Mazzeo, Stefano Meletti, Chiara Milano, Annacarmen Nilo, Biagio Orlando, Francesco Paladin, Maria Grazia Pascarella, Chiara Pastori, Giada Pauletto, Alessia Peretti, Gabriella Perri, Marianna Pezzella, Marta Piccioli, Pietro Pignatta, Nicola Pilolli, Francesco Pisani, Laura Rosa Pisani, Fabio Placidi, Patrizia Pollicino, Vittoria Porcella, Silvia Pradella, Monica Puligheddu, Stefano Quadri, Pier Paolo Quarato, Rui Quintas, Rosaria Renna, Giada Ricciardo Rizzo, Adriana Rum, Enrico Michele Salamone, Ersilia Savastano, Maria Sessa, David Stokelj, Elena Tartara, Mario Tombini, Gemma Tumminelli, Anna Elisabetta Vaudano, Maria Ventura, Ilaria Viganò, Emanuela Viglietta, Aglaia Vignoli, Flavio Villani, Elena Zambrelli, Lelia Zummo.

Disclosures

Simona Lattanzi has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Angelini, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma, and has served on advisory boards for Angelini, Arvelle Therapeutics, Bial, EISAI, and GW Pharmaceuticals. Laura Canafoglia has received consultancy fee from Eisai. Maria Paola Canevini has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Bial, Eisai, Italfarmaco, Sanofi, and UCB Pharma. Sara Casciato has participated in pharmaceutical industry-sponsored symposia for Eisai, UCB Pharma and Lusofarmaco. Valentina Chiesa has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Eisai and UCB Pharma. Edoardo Ferlazzo has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Angelini, Arvelle Therapeutics, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, and UCB Pharma. Angela La Neve has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Angelini, Arvelle Therapeutics, Bial, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Mylan, Sanofi, and UCB Pharma. Patrizia Pulitano has received consulting fees or speaker honoraria from UCB Pharma and Eisai. Federica Ranzato has received speaker’s fees from Eisai, UCB, and Livanova. Eleonora Rosati has received fees for participation in advisory board or scientific consultation from Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Bial, and UCB Pharma. Laura Tassi has received speaker’s or consultancy fees from Arvelle Therapeutics, Eisai and UCB Pharma. Carlo Di Bonaventura has received consulting fees or speaker honoraria from UCB Pharma, Eisai, GW Pharmaceuticals, Bial, and Lusopharma. Emanuele Cerulli Irelli, Filippo Dainese, Giovanni De Maria, Giuseppe Didato, Giancarlo Di Gennaro, Giovanni Falcicchio, Martina Fanella, Massimo Gangitano, Oriano Mecarelli, Elisa Montalenti, Alessandra Morano, Federico Piazza and Chiara Pizzanelli have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

BRIVAFIRST was approved by the ethics committee at any participating site and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Prior to participation in the study, informed consent (e.g., explanation of the purposes of the research, information about handling of personal data and results of the research, description of the procedures adopted for ensuring data protection) was obtained from any patient or from one of the parents or from the legal representative.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

The members of the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk Study (BRIVAFIRST) Group are listed in the Acknowledgements section.

Contributor Information

Simona Lattanzi, Email: alfierelattanzisimona@gmail.com.

BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk Study (BRIVAFIRST) Group:

Angela Alicino, Michele Ascoli, Giovanni Assenza, Federica Avorio, Valeria Badioni, Paola Banfi, Emanuele Bartolini, Luca Manfredi Basili, Vincenzo Belcastro, Simone Beretta, Irene Berto, Martina Biggi, Giuseppe Billo, Giovanni Boero, Paolo Bonanni, Jole Bongorno, Francesco Brigo, Emanuele Caggia, Claudia Cagnetti, Carmen Calvello, Edward Cesnik, Gigliola Chianale, Domenico Ciampanelli, Roberta Ciuffini, Dario Cocito, Donato Colella, Margherita Contento, Cinzia Costa, Eduardo Cumbo, Alfredo D’Aniello, Francesco Deleo, Jacopo C DiFrancesco, Roberta Di Giacomo, Alessandra Di Liberto, Elisabetta Domina, Fedele Dono, Vania Durante, Maurizio Elia, Anna Estraneo, Giacomo Evangelista, Maria Teresa Faedda, Ylenia Failli, Elisa Fallica, Jinane Fattouch, Alessandra Ferrari, Florinda Ferreri, Giacomo Fisco, Davide Fonti, Francesco Fortunato, Nicoletta Foschi, Teresa Francavilla, Rosita Galli, Stefano Gazzina, Anna Teresa Giallonardo, Filippo Sean Giorgi, Loretta Giuliano, Francesco Habetswallner, Francesca Izzi, Benedetta Kassabian, Angelo Labate, Concetta Luisi, Matteo Magliani, Giulia Maira, Luisa Mari, Daniela Marino, Addolorata Mascia, Alessandra Mazzeo, Stefano Meletti, Chiara Milano, Annacarmen Nilo, Biagio Orlando, Francesco Paladin, Maria Grazia Pascarella, Chiara Pastori, Giada Pauletto, Alessia Peretti, Gabriella Perri, Marianna Pezzella, Marta Piccioli, Pietro Pignatta, Nicola Pilolli, Francesco Pisani, Laura Rosa Pisani, Fabio Placidi, Patrizia Pollicino, Vittoria Porcella, Silvia Pradella, Monica Puligheddu, Stefano Quadri, Pier Paolo Quarato, Rui Quintas, Rosaria Renna, Giada Ricciardo Rizzo, Adriana Rum, Enrico Michele Salamone, Ersilia Savastano, Maria Sessa, David Stokelj, Elena Tartara, Mario Tombini, Gemma Tumminelli, Anna Elisabetta Vaudano, Maria Ventura, Ilaria Viganò, Emanuela Viglietta, Aglaia Vignoli, Flavio Villani, Elena Zambrelli, and Lelia Zummo

References

- 1.Rogawski MA. Brivaracetam: a rational drug discovery success story. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:1555–1557. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.European Medicines Agency. Brivaracetam. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/overview/briviact-epar-medicine-overview_en.pdf. Accessed July 2022.

- 3.Lattanzi S, Trinka E, Zaccara G, et al. Third-generation antiseizure medications for adjunctive treatment of focal-onset seizures in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Drugs. 2022;82:199–218. doi: 10.1007/s40265-021-01661-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Foo EC, Geldard J, Peacey C, Wright E, Eltayeb K, Maguire M. Adjunctive brivaracetam in focal and generalized epilepsies: a single-center open-label prospective study in patients with psychiatric comorbidities and intellectual disability. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;99:106505. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2019.106505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lattanzi S, Canafoglia L, Canevini MP, et al. Adjunctive brivaracetam in older patients with focal seizures: evidence from the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk Study (BRIVAFIRST) Drugs Aging. 2022;39:297–304. doi: 10.1007/s40266-022-00931-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lattanzi S, Canafoglia L, Canevini MP, et al. Brivaracetam as add-on treatment in patients with post-stroke epilepsy: real-world data from the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk Study (BRIVAFIRST) Seizure. 2022;97:37–42. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2022.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villanueva V, López-González FJ, Mauri JA, Rodriguez-Uranga J, et al. BRIVA-LIFE-A multicenter retrospective study of the long-term use of brivaracetam in clinical practice. Acta Neurol Scand. 2019;139:360–368. doi: 10.1111/ane.13059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lattanzi S, Canafoglia L, Canevini MP, et al. Adjunctive brivaracetam in focal epilepsy: real-world evidence from the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk STudy (BRIVAFIRST) CNS Drugs. 2021;35:1289–1301. doi: 10.1007/s40263-021-00856-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lattanzi S, Canafoglia L, Canevini MP, et al. Correction to: adjunctive brivaracetam in focal epilepsy: real-world evidence from the BRIVAracetam add-on First Italian netwoRk Study (BRIVAFIRST) CNS Drugs. 2021;35:1329–1331. doi: 10.1007/s40263-021-00868-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58:522–530. doi: 10.1111/epi.13670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lattanzi S, Ascoli M, Canafoglia L, et al. Sustained seizure freedom with adjunctive brivaracetam in patients with focal onset seizures. Epilepsia. 2022;63:e42–50. doi: 10.1111/epi.17223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Foschi N, Provinciali L, Silvestrini M. Eslicarbazepine acetate as adjunctive treatment in partial-onset epilepsy. Acta Neurol Scand. 2018;137:29–32. doi: 10.1111/ane.12803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:573–577. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:314–319. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schiller Y, Najjar Y. Quantifying the response to antiepileptic drugs: effect of past treatment history. Neurology. 2008;70:54–65. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000286959.22040.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adewusi J, Burness C, Ellawela S, et al. Brivaracetam efficacy and tolerability in clinical practice: a UK-based retrospective multicenter service evaluation. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;106:106967. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.106967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Steinhoff BJ, Christensen J, Doherty CP, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in patients with focal seizures: second interim analysis of 6-month data from a prospective observational study in Europe. Epilepsy Res. 2020;165:106329. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Menzler K, Mross P, Rosenow F, et al. First clinical postmarketing experiences in the treatment of epilepsies with brivaracetam: a retrospective observational multicentre study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e030746. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirsch M, Hintz M, Specht A, Schulze-Bonhage A. Tolerability, efficacy and retention rate of brivaracetam in patients previously treated with levetiracetam: a monocenter retrospective outcome analysis. Seizure. 2018;61:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2018.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zahnert F, Krause K, Immisch I, et al. Brivaracetam in the treatment of patients with epilepsy—first clinical experiences. Front Neurol. 2018;9:38. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steinhoff BJ, Bacher M, Bucurenciu I, et al. Real-life experience with brivaracetam in 101 patients with difficult-to-treat epilepsy—a monocenter survey. Seizure. 2017;48:11–14. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinig I, von Podewils F, Möddel G, et al. Postmarketing experience with brivaracetam in the treatment of epilepsies: a multicenter cohort study from Germany. Epilepsia. 2017;58:1208–1216. doi: 10.1111/epi.13768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lattanzi S, De Maria G, Rosati E, et al. Brivaracetam as add-on treatment in focal epilepsy: a real-world time-based analysis. Epilepsia. 2021;62:e1–e6. doi: 10.1111/epi.16769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karoly PJ, Romero J, Cook MJ, Freestone DR, Goldenholz DM. When can we trust responders? Serious concerns when using 50% response rate to assess clinical trials. Epilepsia. 2019;60:e99–103. doi: 10.1111/epi.16321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldenholz DM, Moss R, Scott J, Auh S, Theodore WH. Confusing placebo effect with natural history in epilepsy: a big data approach. Ann Neurol. 2015;78:329–336. doi: 10.1002/ana.24470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein P, Laloyaux C, Elmoufti S, Gasalla T, Martin MS. Time course of 75%-100% efficacy response of adjunctive brivaracetam. Acta Neurol Scand. 2020;142:175–180. doi: 10.1111/ane.13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klein P, Johnson ME, Schiemann J, Whitesides J. Time to onset of sustained 50% responder status in patients with focal (partial-onset) seizures in three phase III studies of adjunctive brivaracetam treatment. Epilepsia. 2017;58:e21–e25. doi: 10.1111/epi.13631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Verrotti A, Lattanzi S, Brigo F, et al. Pharmacodynamic interactions of antiepileptic drugs: from bench to clinical practice. Epilepsy Behav. 2020;104(Pt A):106939. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2020.106939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Correia FD, Freitas J, Magalhães R, et al. Two-year follow-up with eslicarbazepine acetate: a consecutive, retrospective, observational study. Epilepsy Res. 2014;108:1399–1405. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brodie MJ, Whitesides J, Schiemann J, D'Souza J, Johnson ME. Tolerability, safety, and efficacy of adjunctive brivaracetam for focal seizures in older patients: a pooled analysis from three phase III studies. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lawthom C, Bermejo P, Campos D, McMurray R, Villanueva V. Effectiveness and safety/tolerability of eslicarbazepine acetate in epilepsy patients aged ≥ 60 versus < 60 years: a subanalysis from the Euro-Esli Study. Neurol Ther. 2019;8:491–504. doi: 10.1007/s40120-019-0137-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Foschi N, et al. Adjunctive perampanel in older patients with epilepsy: a multicenter study of clinical practice. Drugs Aging. 2021;38:603–610. doi: 10.1007/s40266-021-00865-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Villanueva V, Holtkamp M, Delanty N, et al. Euro-Esli: a European audit of real-world use of eslicarbazepine acetate as a treatment for partial-onset seizures. J Neurol. 2017;264:2232–2248. doi: 10.1007/s00415-017-8618-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wehner T, Mannan S, Turaga S, et al. Retention of perampanel in adults with pharmacoresistant epilepsy at a single tertiary care center. Epilepsy Behav. 2017;73:106–110. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Villanueva V, López-Gomáriz E, López-Trigo J, et al. Rational polytherapy with lacosamide in clinical practice: results of a Spanish cohort analysis RELACOVA. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ayalew MB, Muche EA. Patient reported adverse events among epileptic patients taking antiepileptic drugs. SAGE Open Med. 2018;4(6):2050312118772471. doi: 10.1177/2050312118772471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zaccara G, Gangemi PF, Cincotta M. Central nervous system adverse effects of new antiepileptic drugs: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled studies. Seizure. 2008;17:405–421. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lattanzi S, Cagnetti C, Foschi N, et al. Brivaracetam add-on for refractory focal epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2016;86:1344–1352. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ben-Menachem E, Mameniškienė R, Quarato PP, et al. Efficacy and safety of brivaracetam for partial-onset seizures in 3 pooled clinical studies. Neurology. 2016;87:314–323. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.