Abstract

Background

Many severe asthma patients with high oral corticosteroid exposure (HOCS) often do not initiate biologics despite being eligible. This study aimed to compare the characteristics of severe asthma patients with HOCS who did and did not initiate biologics.

Methods

Baseline characteristics of patients with HOCS (long-term maintenance OCS therapy for at least 1 year, or ≥4 courses of steroid bursts in a year) from the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR; https://isaregistries.org/), who initiated or did not initiate biologics (anti-lgE, anti-IL5/5R or anti-IL4R), were described at the time of biologic initiation or registry enrolment. Statistical relationships were tested using Pearson’s chi-squared tests for categorical variables, and t-tests for continuous variables, adjusting for potential errors in multiple comparisons.

Results

Between January 2015 and February 2021, we identified 1412 adult patients with severe asthma from 19 countries that met our inclusion criteria of HOCS, of whom 996 (70.5%) initiated a biologic and 416 (29.5%) did not. The frequency of biologic initiation varied across geographical regions. Those who initiated a biologic were more likely to have higher blood eosinophil count (483 vs 399 cells/µL, p=0.003), serious infections (49.0% vs 13.3%, p<0.001), nasal polyps (35.2% vs 23.6%, p<0.001), airflow limitation (56.8% vs 51.8%, p=0.013), and uncontrolled asthma (80.8% vs 73.2%, p=0.004) despite greater conventional treatment adherence than those who did not start a biologic. Both groups had similar annual asthma exacerbation rates in the previous 12 months (5.7 vs 5.3, p=0.147).

Conclusion

Around one third of severe HOCS asthma patients did not receive biologics despite a similar high burden of asthma exacerbations as those who initiated a biologic therapy. Other disease characteristics such as eosinophilic phenotype, serious infectious events, nasal polyps, airflow limitation and lack of asthma control appear to dictate biologic use.

Keywords: severe asthma, biologics, real-world, treatment pattern, patient characteristics

Introduction

A major burden of severe asthma (SA) is the ongoing risk of severe exacerbations defined (according to the American Thoracic Society [ATS]/European Respiratory Society [ERS] Task Force) as a worsening of asthma which require use of oral corticosteroid (OCS) for at least 3 days, hospitalization, or emergency department (ED) visit.1 The ongoing risk of recurrent severe exacerbations and other chronic daily symptoms lead to substantially increased healthcare resource use and costs and impaired quality of life2,3 due to both acute care as well as the onset of various OCS-related side-effects and adverse outcomes.4,5 OCS are commonly prescribed to treat or reduce the risk of inflammatory flare-ups after an asthma exacerbation (episodic use) or when asthma is still uncontrolled despite standard high-dose inhaled therapy (long-term maintenance use).6 In Europe, 14‒44% of all asthma patients studied used OCS, 6‒9% were high OCS users (defined as OCS use of at least 450 mg prescribed in 3 months) at some point.7 In the United States, the prevalence of OCS use is even higher: 65% of SA patients used OCS and 19% were classified as high OCS users, using the same definition.8 In particular, long-term (maintenance) OCS is prevalent in approximately 20% to 60% of SA patients.9–11

In previous studies, the available therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (“biologics”, including omalizumab, mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab and dupilumab) were found to reduce exacerbation frequency when used as add-on therapies to standard asthma therapies.12 They can also improve asthma control and lung function, and some (mepolizumab, reslizumab, benralizumab and dupilumab) have shown OCS-sparing effects.12,13 In a preliminary study of a large international SA cohort,11 we have previously detected marked variability in the prescription criteria of biologics across country settings, assessed using the biologic accessibility score (BACS), a composite score incorporating 10 commonly used biologic eligibility criteria.14 Referenced to European Medicines Agency marketing authorization specifications, a higher score reflected easier biologic access. The study found that for omalizumab, mepolizumab, benralizumab and dupilumab, only two, one, four and seven countries out of a total of 28, had equivalent or easier biologic access than that advocated by the EMA, and in all countries reslizumab was more difficult to access when compared to EMA eligibility criteria.14 Biologic prescription criteria are informed by the strict inclusion/exclusion criteria in randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that show higher efficacy among T2-high patients, as well as differences in national prescribing criteria and reimbursement considerations. However, only about 10% of SA patients are eligible for enrollment in the Phase III trials, with a significant number of patients being excluded because of stipulations for airflow limitation, bronchodilator reversibility and smoking history.15 For this reason, it is important to characterize SA patients with high oral corticosteroid exposure (HOCS) who were stepped up to a biologic therapy in real world settings. Precise profiling of these patients versus those who were not initiated on biologics will provide insight into this important segment of SA patients, enabling subsequent investigation into the real-world effects and cost-effectiveness of biologics in patients with HOCS.

Based on a large international cohort of SA patients with HOCS exposure, this study aims to identify the demographic and clinical features, including medication usage and co-morbidities, that are associated with those who were initiated on biologic therapy, compared to those who were not.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Data Source

International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR; http://isaregistries.org/), the largest adult SA registry in the world, and which is continually expanding, comprises de-identified, patient-level, longitudinal, real-life, standardized data from existing and newly created SA registries of 29 countries for over 10,000 patients.16–19 For this study in particular, ISAR initially collected data for 5379 patients, using a core set of variables, from 19 countries (Argentina, Australia, Bulgaria, Canada, Colombia, Denmark, Greece, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Kuwait, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Spain, Taiwan, United Arab Emirates and the United Kingdom) between January 2015 and February 2021.18 The ISAR database has ethical approval from the Anonymised Data Ethics Protocols and Transparency (ADEPT) committee (ADEPT0218). This study was designed, implemented, and reported in compliance with the European Network Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance Code of Conduct (EMA 2014; EUPAS33582) and with all applicable local and international laws and regulations.

Study Cohort

This study included patients aged 18 years or older at enrolment and who have SA (ie receiving treatment at GINA 2018 Step 5 or with uncontrolled asthma at GINA Step 4).20 A summary of how each registry diagnoses asthma and categorizes SA is provided in Supplementary Table 1. In addition, patients in the study cohort were also required to have a history of HOCS exposure use for at least 12 months prior to the index date, defined as either having long-term (maintenance) use of OCS for at least 12 months prior, or using 4 or more courses of rescue steroid bursts for a 12-month period at baseline; a more strict definition than used in previous studies.7,8 Patients who had received bronchial thermoplasty, any prior history of biologic use, or who had inadequate background data at the date of initiation, were excluded from the analysis.

The index date was defined as the date of biologic initiation for the Biologic Initiated group, assigned for those who received biologics (hereafter referred to as biologic initiators), and the date of ISAR enrolment for the Biologic not Initiated group (hereafter referred to as biologic non-initiators), assigned for those who never received biologics. The baseline period covers the 12 months prior to index date.

Study Variables

Variables of interest included demographic variables (eg, age, age of asthma onset, gender, ethnicity, body mass index), smoking history, asthma duration, frequency of exacerbation, severity of exacerbation, asthma control status, positive testing for allergen tests, co-morbidities (OCS related and un-related), healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), biomarker concentrations (fractional exhaled nitric oxide [FeNO], total and specific serum IgE, and blood eosinophil count [BEC]), lung function, and treatment regimen. In addition, patients were also classified into different grades of eosinophilic phenotype likelihood, following a predefined eosinophilic asthma phenotype algorithm, based on highest BEC, long-term maintenance OCS use, elevated FeNO, presence of nasal polyps, and adult-onset of asthma.21 A full description of variables collected is provided in Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Table 3. We also calculated the Biologic Accessibility Score (BACS) for different groups of biologics associated with each country, which incorporates ten access prescription criteria, reflecting that country’s criteria to prescribe a particular biologic, and the “ease” of receiving the various biologics in asthma. A full description of the BACS index scores and the prescription criteria components are provided in Supplementary Table 4.14 Range of exacerbation counts is provided by counter in Supplementary Table 5.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were computed for all demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline, based on whether they were continuous variables or categorical measures, as appropriate. These statistics were reported separately for those who did and did not initiate biologic therapy. Statistical relationships were tested using Pearson’s chi-squared tests for categorical variables, and t-tests for continuous variables. To account for potential errors in multiple comparisons, we applied the robust Benjamini‐Hochberg (B-H) procedure,22 which calculated the critical p-value for significance in multiple testing, accepting up to 10% of false discovery rate. Statistical significance was defined as a p-value lower than the B-H critical p-value for multiple comparisons. Stata version 17 (College Station, TX, USA) was used to conduct all statistical analyses.

Results

Study Cohorts

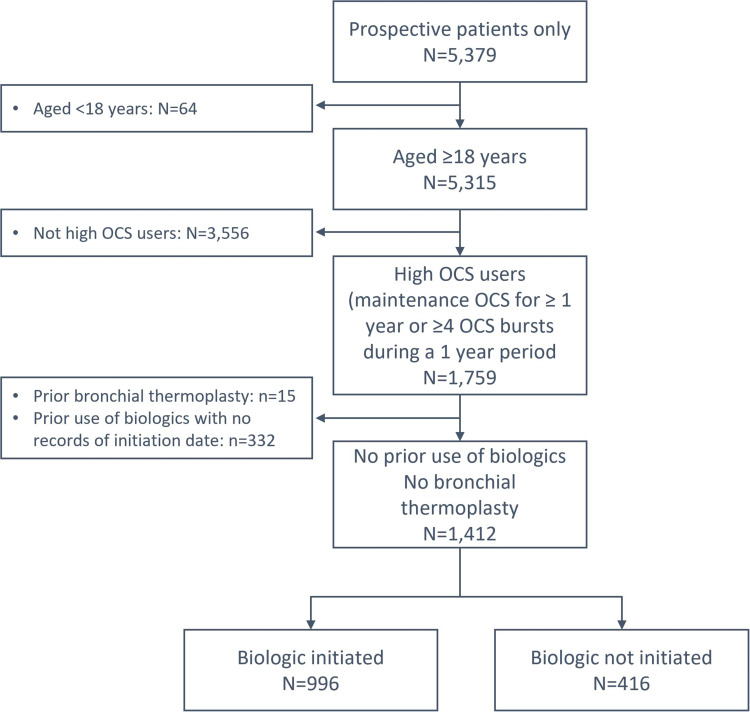

Among 5379 prospective adult patients with SA from the 19 ISAR participating countries, 1412 were HOCS patients who met the inclusion criteria, as shown in Figure 1. Of these, 996 (70.5%) initiated biologics and 416 (29.5%) did not. Of the biologic therapies, mepolizumab made up the majority (n=604, 62.7%; first available since 2015), followed by omalizumab (n=260; 27.0%; since 2003). A relatively smaller proportion of patients initiated benralizumab (n=82; 8.5%; since 2017), reslizumab (n=12, 1.2%; since 2016), or dupilumab (n=6; 0.6%; since 2016).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of cohort creation.

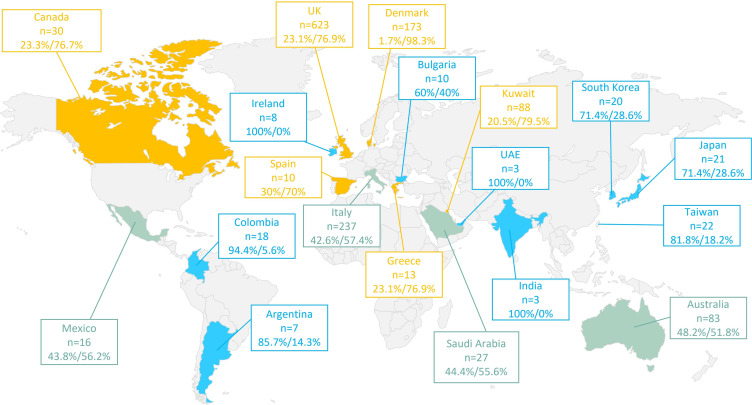

Geographic Distribution

Geographical variation in the initiation of biologics was noted (Figure 2). However, there was no clear relationship between the proportion of patients who initiated biologics and the country-specific BACS scores.

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of adult severe asthma patients with high oral corticosteroid exposure enrolled in ISAR according to biologic initiation status. ISAR: International Severe Asthma Registry. Data are presented as % not initiated/% initiated. Green: approximately equal proportion of biologic non-initiators to initiators; Blue: More likely not to initiate biologics; Yellow: more likely to initiate biologics.

Demographic Characteristics (Table 1)

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics for ISAR Patients with Severe Asthma and High Oral Corticosteroid Exposure Who Were and Were Not Initiated on Biologic (Bx) Therapy

| BX Not Initiated | BX Initiated | P-value | B‐H Critical P value Threshold for Significance in Multiple Testing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs | n = 416 | n = 996 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 53.2 (14.5) | 51.7 (13.9) | 0.075 | |

| 18–34, n (%) | 50 (12.0) | 131 (13.2) | 0.010 | 0.028 |

| 35–54, n (%) | 153 (36.8) | 418 (42.0) | ||

| 55–79, n (%) | 203 (48.8) | 440 (44.2) | ||

| 80+, n (%) | 10 (2.4) | 7 (0.7) | ||

| Gender | n = 416 | n = 996 | ||

| Female, n (%) | 277 (66.6) | 609 (61.1) | 0.050 | 0.040 |

| Race/Ethnicity | n = 375 | n = 887 | ||

| Caucasian, n (%) | 244 (65.1) | 689 (77.7) | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| Asian, n (%) | 65 (17.3) | 62 (7.0) | ||

| African, n (%) | 10 (2.7) | 36 (4.1) | ||

| Mixed, n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 17 (1.9) | ||

| Other†, n (%) | 55 (14.7) | 83 (9.4) | ||

| BMI Category, Kg/m2 | n = 410 | n = 960 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 29.7 (7.7) | 29.3 (6.8) | 0.280 | 0.066 |

| Underweight (BMI <18.5), n (%) | 11 (2.7) | 13 (1.4) | 0.310 | 0.071 |

| Normal (BMI 18.5 to <25), n (%) | 106 (25.9) | 264 (27.5) | ||

| Overweight (BMI 25 to <30), n (%) | 126 (30.7) | 309 (32.2) | ||

| Obese (BMI ≥30), n (%) | 167 (40.7) | 374 (39.0) | ||

| Tobacco smoking status † | n = 410 | n = 936 | ||

| Current smoker, n (%) | 23 (5.6) | 23 (2.5) | 0.010 | 0.029 |

| Ex-smoker, n (%) | 106 (25.9) | 267 (28.5) | ||

| Non-smoker, n (%) | 281 (68.5) | 646 (69.0) | ||

| Tobacco smoking pack-years† | n = 117 | n = 249 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 15.25 (16.31) | 18.97 (17.62) | 0.050 | 0.041 |

| <6, n (%) | 41 (35.0) | 56 (22.5) | 0.011 | 0.033 |

| ≥6, n (%) | 76 (65.0) | 193 (77.5) | ||

| ≤10, n (%) | 67 (57.3) | 105 (42.2) | 0.007 | 0.021 |

| >10, n (%) | 50 (42.7) | 144 (57.8) |

Notes: †does not include hookah smoking. Test statistics: Pearson Chi Square test for categorical variables with > 2 categories, McNemar’s test for categorical variables with 2 categories and T-test for continuous variables.

Abbreviations: B-H, Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure; BMI, body mass index; ISAR, International Severe Asthma Registry; SD, standard deviation.

Mean age and BMI were similar across biologic initiated and non-initiated groups (age, 51.7 vs 53.2 years, p=0.08; BMI, 29.3 vs 29.7 kg/m2, p=0.28). However, compared to those who did not initiate biologics, biologic initiators were more likely to be Caucasian (77.7% vs 65.1%, p<0.001).

Clinical Characteristics (Table 2 and Figure 3)

Table 2.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics for ISAR Patients with Severe Asthma and High Oral Corticosteroid Exposure Who Were and Were Not Initiated on Biologic (Bx) Therapy

| BX Not Initiated | BX Initiated | P-value | B‐H Critical P value Threshold for Significance in Multiple Testing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of asthma onset | N=402 | N=876 | 0.150 | 0.057 |

| Mean (SD) | 29.5 (18.7) | 27.9 (18.7) | ||

| Asthma duration | N=394 | N=859 | 0.910 | 0.098 |

| Mean (SD) | 23.8 (16.3) | 23.7 (16.7) | ||

| Asthma control* | N=381 | N=777 | 0.004 | 0.017 |

| Controlled, n (%) | 26 (6.8) | 51 (6.6) | ||

| Partially controlled, n (%) | 76 (20.0) | 98 (12.6) | ||

| Uncontrolled, n (%) | 279 (73.2) | 628 (80.8) | ||

| No. asthma exacerbations in the past year (excluding cases with 0 exacerbations) | N=334 | N=849 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.3 (4.0) | 5.7 (3.9) | 0.147 | 0.055 |

| 1, n (%) | 26 (7.8) | 75 (8.8) | 0.009 | 0.024 |

| 2, n (%) | 39 (11.7) | 82 (9.7) | ||

| 3, n (%) | 28 (8.4) | 61 (7.2) | ||

| 4, n (%) | 85 (25.5) | 181 (21.3) | ||

| 5, n (%) | 60 (18.0) | 112 (13.2) | ||

| ≥6, n (%) | 96 (28.7) | 338 (39.8) | ||

| Adherence* | N=327 | N=873 | ||

| Adherent, n (%) | 249 (76.2) | 774 (88.7) | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| Poor: Clinical impression, n (%) | 25 (7.7) | 12 (1.4) | ||

| Poor: Prescription records, n (%) | 53 (16.2) | 87 (10.0) | ||

| Positive allergen test | ||||

| Serum specific IgE test to allergens | N=340 | N=926 | ||

| Positive, n (%) | 112 (32.9) | 396 (42.8) | 0.002 | 0.012 |

| Skin prick test to allergens | N=340 | N=926 | ||

| Positive, n (%) | 99 (29.1) | 305 (32.9) | 0.196 | 0.060 |

| Healthcare resource utilization | ||||

| N=416 | N=996 | |||

| Emergency department visit, N (%) | 157 (37.7) | 321 (32.2) | 0.046 | 0.038 |

| Hospital admission, N (%) | 131 (31.5) | 286 (28.7) | 0.297 | 0.069 |

| Invasive ventilation (ever), N (%) | 27 (6.5) | 69 (6.9) | 0.766 | 0.088 |

| Post-bronchodilator (BD) lung function | ||||

| Post-BD FEV1, % predicted | N=296 | N=840 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 72.69 (23.29) | 73.09 (34.59) | 0.854 | 0.091 |

| Post-BD FEV1/FVC | N=282 | N=826 | 0.008 | 0.022 |

| Mean (SD) | 0.71 (0.18) | 0.67 (0.22) | ||

| Post-BD FEV1/FVC < 0.7, n (%) | N=282 136 (51.8) |

N=826 469 (56.8) |

0.013 | 0.034 |

| Biomarkers | ||||

| Serum total IgE, IU (mL) | N=313 | N=882 | ||

| <150, n (%) | 165 (52.7) | 396 (44.9) | 0.055 | 0.045 |

| 150–400, n (%) | 67 (21.4) | 229 (26.0) | ||

| >400, n (%) | 81 (25.9) | 257 (29.1) | ||

| BEC (/µL) | N=329 | N=919 | ||

| Highest, Mean (SD) | 398.9 (371.4) | 482.8 (468.7) | 0.003 | 0.014 |

| 150, n (%) | 88 (26.8) | 220 (23.9) | 0.057 | 0.047 |

| >150 to ≤ 300, n (%) | 90 (27.4) | 220 (23.9) | ||

| >300 to ≤ 450, n (%) | 43 (13.1) | 99 (10.8) | ||

| >450, n (%) | 108 (32.8) | 380 (41.4) | ||

| FeNO, ppb | N=218 | N=701 | 0.010 | 0.031 |

| <25, n (%) | 87 (39.9) | 205 (29.2) | ||

| 25–50, n (%) | 53 (24.3) | 220 (31.4) | ||

| >50, n (%) | 78 (35.8) | 276 (39.4) | ||

| Low T2 biomarker, n (%) | N=183 | N=666 | ||

| 30 (16.4) | 58 (8.7) | 0.003 | 0.016 | |

| High T2 biomarker, n (%) | N=183 | N=666 | ||

| 75 (41.0) | 282 (42.3) | 0.742 | 0.086 | |

| ISAR gradient eosinophilic phenotype | N=325 | N=911 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Grade 0 (unlikely), n (%) | 7 (2.2) | 2 (0.2) | ||

| Grade 1 (least likely), n (%) | 35 (10.8) | 20 (2.2) | ||

| Grade 2 (Likely), n (%) | 62 (19.1) | 62 (6.8) | ||

| Grade 3 (most likely), n (%) | 221 (68.0) | 827 (90.8) | ||

| Co-morbidities | ||||

| Potential OCS-related co-morbidities | ||||

| Anxiety, n (%) | N=230 31 (13.5) |

N=260 36 (13.9) |

0.906 | 0.097 |

| Depression, n (%) | N=227 25 (11.0) |

N=254 23 (9.1) |

0.474 | 0.079 |

| Osteoporosis, n (%) | N=304 52 (17.1) |

N=611 67 (11.0) |

0.009 | 0.026 |

| Peptic ulcer, n (%) | N=185 10 (5.4) |

N=205 6 (2.9) |

0.218 | 0.062 |

| Type II diabetes, n (%) | N=170 31 (18.2) |

N=210 29 (13.8) |

0.239 | 0.064 |

| History of Pneumonia, n (%) | N=184 15 (8.2) |

N=205 16 (7.8) |

0.900 | 0.095 |

| Cataract, n (%) | N=128 9 (7.0) |

N=108 5 (4.6) |

0.437 | 0.076 |

| Embolism, n (%) | N=126 2 (1.6) |

N=105 2 (1.9) |

0.854 | 0.093 |

| Glaucoma, n (%) | N=128 2 (1.6) |

N=108 5 (4.6) |

0.166 | 0.059 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | N=128 3 (2.3) |

=104 1 (1.0) |

0.421 | 0.074 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | N=166 3 (1.8) |

N=148 5 (3.4) |

0.378 | 0.072 |

| Renal failure, n (%) | N=185 2 (1.1) |

N=205 0 (0.0) |

0.136 | 0.053 |

| Sleep apnea, n (%) | N=173 29 (16.8) |

N=231 35 (15.2) |

0.661 | 0.081 |

| Stroke, n (%) | N=166 0 (0.0) |

N=146 1 (0.7) |

0.286 | 0.067 |

| T2 Comorbidities (ever) | N=416 | N=996 | ||

| Allergic rhinitis, n (%) | 168 (40.4) | 313 (31.4) | 0.001 | 0.010 |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis, n (%) | 83 (20.0) | 246 (24.7) | 0.054 | 0.043 |

| Eczema, n (%) | 38 (9.1) | 98 (9.8) | 0.682 | 0.084 |

| Nasal polyps, n (%) | 98 (23.6) | 351 (35.2) | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| Other | ||||

| Anaphylaxis event, n (%) | N=197 5 (2.5) |

N=399 2 (0.5) |

0.030 | 0.036 |

| Cancer event, n (%) | N=199 13 (6.5) |

N=393 8 (2.0) |

0.005 | 0.019 |

| Serious infection event, n (%) | N=196 26 (13.3) |

N=396 194 (49.0) |

<0.001 | 0.009 |

| Asthma therapy | ||||

| Add-on treatment to ICS/LABA | N=416 | N=996 | ||

| Long term OCS, n (%)† | 247 (59.4) | 612 (61.5) | 0.467 | 0.078 |

| LTRA, n (%) | 181 (43.5) | 427 (42.9) | 0.825 | 0.090 |

| Long-term macrolide, n (%) | 25 (6.0) | 54 (5.4) | 0.661 | 0.083 |

| Steroid-sparing, n (%) | 8 (1.9) | 8 (0.8) | 0.070 | 0.050 |

| Theophylline, n (%) | 64 (15.4) | 169 (17.0) | 0.465 | 0.100 |

| LAMA, n(%) | 216 (51.9) | 463 (46.5) | 0.062 | 0.048 |

Notes: *Treatment adherence was evaluated through a mix of methods in different countries in ISAR registry. †LTOCS: OCS therapy for at least 3 months.

Abbreviations: BEC, blood eosinophil count; B-H, Benjamini-Hochberg Procedure; FeNO, fractional exhaled nitric oxide; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; GINA, Global Initiative for Asthma; ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; IgE, Immunoglobulin E; ISAR, International Severe Asthma Registry; LABA, long-acting β2-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic; LTRA, leukotriene receptor antagonist; OCS, oral corticosteroid; SD, standard deviation.

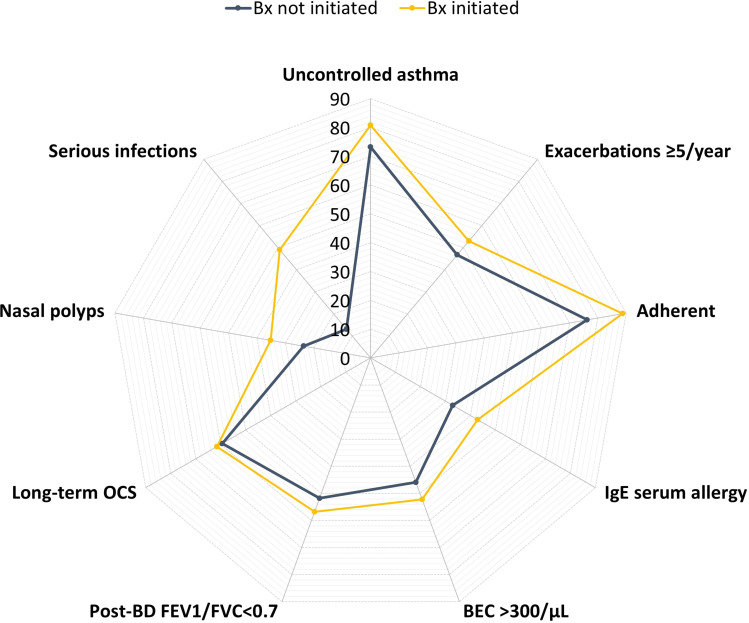

Figure 3.

Clinical characteristics of adult severe asthma patients with high oral corticosteroid exposure enrolled in ISAR who did and did not initiate biologic therapy.

Abbreviations: BEC, blood eosinophil count; BD, bronchodilator; Bx, biologic; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; IgE, immunoglobulin E; ISAR, International Severe Asthma Registry; OCS, oral corticosteroid.

Asthma Status

Biologic initiators were comparable to non-initiators with regard to age of onset of asthma (year, 27.9 vs 29.5, p=0.15), duration of asthma (year, 23.7 vs 23.8, p=0.91), and number of asthma exacerbations over the past year (5.7 vs 5.3, p=0.15). However, patients who initiated biologics were more likely to have uncontrolled asthma (80.8% vs 73.2%, p=0.004) as defined by either GINA criteria, Asthma Control Questionnaire or Asthma Control Test, as well as better treatment adherence as defined by a mix of setting-specific methods (88.7% vs 76.2%, p<0.001), compared to those who did not initiate biologics.

Lung Function

Patients who initiated biologics had similar post-bronchodilator FEV1 as a percentage of predicted FEV1 (73.1% vs 72.7%, p=0.85), and a modestly greater degree of airflow limitation according to the proportion with a FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 0.7 (56.8% vs 51.8%, p=0.013), compared to non-initiators.

Eosinophilic Asthma

Patients who initiated biologics also had a higher mean BEC (483/µL vs 399/µL, p=0.003), slightly higher FeNO concentrations (25–50 ppb, 31.4% vs 24.3%; >50 ppb, 39.4% vs 35.8%, p=0.010), and were more likely to be of ISAR Grade 3 eosinophilic phenotype (90.8% vs 68.0%, p<0.001), compared to non-initiators. Of note, there were fewer biologic initiators with low T2 biomarkers compared to non-initiators (8.7% vs 16.4%, p=0.003), defined as BEC <150/µL and FeNO<25ppb. However, the proportion of high T2 biomarkers were similar between biologic initiators and non-initiators (42.3% vs 41.0%, p=0.742), defined as BEC ≥300/µL and FeNO≥30 ppb.

Allergic Asthma

Similar proportions of patients tested positive for skin prick allergen tests (32.9% vs 29.1%, p=0.20), but more biologic initiators had a positive serum allergen test (42.8% vs 32.9%, p=0.002) compared to non-initiators.

Current Medication and Comorbidities

The distribution of ICS/LABA add-on therapies and most co-morbidities were similar across groups. However, patients who initiated biologics were less likely to have osteoporosis (11.0% vs 17.1%, p=0.009), allergic rhinitis (31.4% vs 40.4%, p=0.001), cancer (2.0% vs 6.5%, p=0.005), and anaphylaxis (0.5% vs 2.5%, p=0.030), compared to non-initiators. On the other hand, biologic initiators were more likely to have a serious infection, defined as an infection that required hospitalization, invasive or non-invasive ventilation, IV antibiotics, or that resulted in a fatal outcome (49.0% vs 13.3%, p<0.001), and were also more likely to have nasal polyps (35.2% vs 23.6%, p<0.001).

Health Services Use in the Past Year

Both biologic initiators and non-initiators had similar proportions of patients with hospital admissions (28.7% vs 31.5%, p=0.30) and ICU admissions involving use of invasive ventilations (6.9% vs 6.5%, p=0.77). Although biologic initiators tended to have a lower proportion of patients with emergency department visits (32.2% vs 37.7%), the difference did not reach significance after the B-H adjustment for multiple comparison errors (p-value of 0.046 > B-H significance threshold of 0.038).

Discussion

In the ISAR cohort, the initiation of biologic therapies varied across countries. Nearly one third of SA patients with HOCS did not receive biologics, but these patients had similarly high frequencies of asthma exacerbation and HCRU as biologic initiators, suggesting that exacerbation history was not driving biologic prescription even though it is an important prescription criterion in many countries.14 On the other hand, eosinophilic asthma defined in terms of elevated biomarkers for airway inflammation (eg, BEC, nasal polyps), uncontrolled asthma despite treatment adherence, and airway limitation, as well as other co-morbidities that often accompany severe disease such as the occurrence of serious infection, appeared to be potential decision determinants for biologic initiation. The use of both endotype and phenotype biomarkers to direct biologic prescription decisions is in line with a precision medicine-based approach, and the 2021 GINA strategy recommendations.23

The decision to initiate biologics exhibited a clear geographic pattern. For instance, SA patients with HOCS in UK, Denmark, Italy and Kuwait were more likely to initiate biologics than not. This pattern was related to country-income level (Eg, East Asia versus Middle East and developed countries versus low-to-middle income countries). Others have found that higher income level and better insurance coverage are associated with biologic initiation.24 There was also noticeable inconsistency between the initiation of biologics and country-specific biologic accessibility, suggesting that prescription criteria, and by extension, biologic accessibility, were not the sole determinants for biologic initiation in certain countries. Moreover, as a number of biologics only became available in 2015 and 2016, and our data were retrieved from 2015 to 2021, the lack of biologic availability may have hindered biologic initiation in some countries.

Our finding that a considerable portion (29%) of SA patients with HOCS did not receive biologics was in agreement with a recent ISAR publication, which showed that 51.1% of patients with SA (but not necessarily HOCS) received regular intermittent OCS, whereas only 25.4% were on biologics.11 Although long-term OCS use is associated with numerous adverse health outcomes,4,5 greatly increased healthcare costs and impaired quality of life,2,3 biologics such as mepolizumab, benralizumab and dupilumab have demonstrated steroid sparing effect in large clinical trials.25–27 Considering the further benefits of biologics in reducing the burden of asthma exacerbations, our finding highlights the need to weigh up the potential harms of long-term OCS use with the benefits of biologics when considering the treatment of severe asthma.

Interestingly, exacerbation frequency and HCRU did not appear to increase the likelihood of biologic initiation in our cohort of SA patients; a surprising finding when bearing in mind that these patients in both groups were on HOCS but still experienced on average more than 5 exacerbations in the prior year, and that a history of exacerbation is a prerequisite of biologic use according to both biologic indications and country-specific eligibility criteria.14 A recent international study by Porsbjerg and colleagues found that approximately half of the 28 countries included required two or more severe exacerbations in the previous year (ie, exacerbations that require treatment with OCS or led to ED visit and/or hospitalization) for a biologic prescription.14 Indeed, ‘frequent exacerbators’ are increasingly recognized as an important subgroup for targeted therapy, because these patients account for a disproportionately high proportion of the total asthma exacerbation burden, with frequent exacerbations associated with greatly increased risk of adverse health events and compromised quality of life.13 Recent studies have found that ‘frequent exacerbators’ have the most room for improvement28–30 and so should be particularly considered for biologics.13

Over 40% of SA HOCS patients were with high T2 biomarkers regardless of whether a biologic was initiated. Nonetheless, our study further showed that the initiation of biologic therapy was more likely in those with greater degree of eosinophilic asthma (indicated by higher baseline BEC and greater prevalence of nasal polyps in the biologic initiator group), which was in agreement with recent studies from both the US24 and UK.31 Use of BEC as a criterion for biologic initiation aligns with country-specific biologic eligibility criteria,14 and is likely informed by the positive correlation between higher BEC and better biologic response.32 Similarly, the greater likelihood of biologic initiation in patients with nasal polyps is likely due to the greater exacerbation frequency seen in SA patients with nasal polyps, more OCS bursts, a greater reduction of exacerbation burden on biologics in these patients,33 and the fact that omalizumab, mepolizumab and dupilumab are also indicated for the treatment of nasal polyps.34 In addition, the much higher frequency of severe infectious events in biologic initiators might be another trigger for physicians to initiate biologics,35 because viral respiratory infections are a major cause of asthma exacerbations.36

We found no significant difference between biologic initiators and non-initiators with regard to asthma therapy at baseline. Although patients who initiated biologics were more likely to be fully adherent to their treatment regimen compared to those who did not initiate biologics, they were also more likely to have uncontrolled asthma. A recent ISAR study on global biologic accessibility found that between 43% and 60% of countries surveyed did not require or had not decided on adherence as a criterion for biologic eligibility.14 However, a large systematic review reported that nearly 70% of mepolizumab users with SA have good ICS adherence before and on mepolizumab, while good ICS adherence is associated with greater reductions in OCS dose and exacerbations.37 On the contrary, low adherence to OCS was reported in roughly 40% of SA patients in the U-BIOPRED cohort.38 Of note, treatment adherence was defined by prescription records and clinical impressions, which varied by settings of ISAR cohort. Regardless of subjective or objective measures, the findings that biologic initiators have more uncontrolled asthma and mostly full treatment adherence to ICS was in line with GINA recommendations.23

This study has several limitations. First, given its observational nature, recall bias was almost inevitable Second, other factors such as biologic affordability, insurance coverage administrative burdens, and government reimbursement criteria (all of which are country specific) likely influenced the decision to initiate biologics. Future research to investigate physician reasons to prescribe and not prescribe biologics is warranted. In addition, there was also potential for confounding by country (eg, the UK was over-represented in the biologic initiator group which may have skewed findings) and, like with other registries, patients may not have been truly representative of the real-life asthma population (albeit more representative than RCT populations). Notwithstanding these limitations, we are confident of the representativeness of the ISAR population as the vast majority of severe asthma patients included in all asthma specialist centres elected to participate in ISAR, or else data were collected directly from EMR embedded registries. A major strength of this study is its size, including a more heterogenous population than that included in randomized controlled trials, with greater generalizability to real life. The global coverage of ISAR, including standardized data from 19 countries, enabled us to explore the clinical characteristics driving initiation of biologics in everyday clinical practice. Our study cohort possessed an extensive collection of clinical information, social and health determinants, enabling a thorough investigation of patient characteristics and a longitudinal follow-up for risk prediction modelling and/or comparative effectiveness study of biologic initiation.

Conclusions

Eosinophilic phenotype, serious infectious events, nasal polyps, airflow limitation and inadequate asthma control appear to encourage physicians to prescribe biologic therapy for SA patients with HOCS in real life. On the other hand, one third of severe HOCS asthma patients did not receive biologics despite similar exacerbation frequency and HCRU as those who initiated a biologic therapy. These findings suggest the need to consider multiple characteristics to guide the initiation of biologics in SA patients, which will optimize efficiency and cost-effectiveness.39–41 Future research should include a rigorous method to ensure comparability of the treatment arms, such as propensity scores, to assess the real-world effectiveness of biologics over time in SA patients with HOCS. In addition, we need to develop an individualized treatment algorithm to guide the initiation of biologics. The ISAR cohort could be suitable for both of these studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. James Zangrilli and Dr. Alex de Giorgio-Miller for their instrumental contributions to the study concept, Mr. Joash Tan (BSc, Hons) of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute (OPRI), for editorial and formatting assistance that supported the development of this publication.

The authors also thank the investigators and participating sites in ISAR for making this research possible.

ISAR Participating Sites:

- Argentina

- Fundacion CIDEA

- Fernandez Hospital Buenos Aires

- Investigaciones en Patologias Respiratorias

- Australia

- Austin Hospital, VIC

- Campbelltown Hospital, NSW

- Concord Hospital, NSW

- Fiona Stanley Hospital, WA

- Flinders Medical Centre, SA

- Frankston Hospital, VIC

- John Hunter Hospital, NSW

- Monash Health, VIC

- Princess Alexandra Hospital, QLD

- Royal Adelaide Hospital, SA

- Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, NSW

- St George Specialist Centre, NSW

- St Vincent Clinic, NSW

- The Alfred Hospital, VIC

- The Prince Charles Hospital, QLD

- Western Health, Footscray, VIC

- Woolcock Institute of Medical Research, NSW

- Bulgaria

- Cvetanka Odjakova, Varna

- Darina Dimova, Plovdiv

- Diana Hristova, Sofia

- Eleonora Stamenova, Sofia

- Katya Noleva, Pazardzhik

- Violina Vasileva, Dupnica

- Canada

- University of British Columbia- Vancouver Coastal Health

- University of British Columbia- Providence Health Care

- University of Alberta

- Toronto Western Hospital

- University Institute of Cardiology and Respirology of Quebec

- Colombia

- Fundacion Neumologica Colombiana, Bogotá

- Institituto Neumológico del Oriente, Bucaramanga

- Hospital Universitario San Ignacio, Bogotá

- Denmark

- Bispebjerg University Hospital

- Aarhus University Hospital

- Gentofte University Hospital

- Hvidovre University Hospital

- Naestved University Hospital

- Odense University Hospital

- Roskilde University Hospital

- Vejle Hospital

- Greece

- Attikon University Hospital, Chaidari

- University Hospital of Ioannina, Ioánnina

- India

- Fortis Hospital, Kolkatta

- West Bengal, D. Y. Patil hospital, Navi Mumbai, Maharashtra

- Ireland

- Royal College of Surgeons

- Italy

- Personalized Medicine, Asthma & Allergy, Humanitas Clinical and Research Center, IRCCS, Rozzano, MI

- UOC Allergology Department, Piacenza

- Department of Experimental and Clinical Biomedical Sciences ”Mario Serio”, Respiratory Unit, Careggi University Hospital, Florence

- Departmental Unit of Allergology and Pneumology, Hospital Institute Fondazione Poliambulanza, Brescia

- Department of Internal Medicine, Clinical Immunology, Clinical Pathology and Infectious Diseases, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Federico II, Naples

- Department of Clinical and Biological Sciences, University of Turin, San Luigi Hospital, Orbassano, Turin

- Department of Clinical and Biomedical Sciences, University of Milan, Respiratory Diseases, Sacco University Hospital, ASST Fatebenefratelli-Sacco, Milan

- Pneumology Unit, Santa Maria Nuova Hospital, Azienda USL di Reggio Emilia IRCCS

- Unit of Immunology, Rheumatology, Allergy and Rare Diseases, IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan

- Division of Respiratory Diseases, Department of Promoting Health, Maternal-Infant. Excellence and Internal and Specialized Medicine (Promise) G. D’Alessandro, University of Palermo, Palermo

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology Unit, Department of Medicine, ”Carlo Poma” Hospital, Mantova

- Respiratory Medicine, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Turin

- Respiratory Unit and Adult Cystic Fibrosis Center, And Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, Fondazione IRCCS Cà Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, University of Milan

- Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Parma

- Division of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, University of Salerno, Fisciano

- Respiratory Department, Division of Respiratory Diseases ”Federico II” University, AO Dei Colli, Naples

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology, University of Turin & AO Mauriziano, Turin

- Division of Pneumology and Allergology, Policlinico, University of Catania

- Allergy Unit, Fondazione Policlinico A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome

- Department of Medicine, Allergy Unit Asthma Center, University of Verona

- Department of Translational Medical Sciences, University of Campania ”L. Vanvitelli”, Naples

- Department of Clinical and Experimental Sciences, University of Brescia, Spedali Civili, Brescia

- Department of Emergency and Organ Transplantation, School and Chair of Allergology and Clinical Immunology, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari

- Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS Catholic University of Rome

- Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of Medicine Catholic, University of the Sacred Heart Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome

- Division of Respiratory Diseases, IRCCS Policlinico San Matteo, Foundation and Department of Internal Medicine and Therapeutics, University of Pavia

- University of Insubria, ICS Maugeri, IRCCS, Varese

- Section of Respiratory Diseases, Medical and Surgical Sciences Department, University of Foggia

- Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Section of Respiratory Diseases, University Magna Graecia, Catanzaro

- Department of Surgery, Medicine, Molecular Biology and Critical Care, University of Pisa

- Japan

- Hiroshima Allergy and Respiratory Clinic

- Kindai University Hospital

- Idaimae Minamiyojo Clinic

- National Mie Hospital

- Kobe University Hospital

- Kyoto University Hospital

- Mie University Hospital

- Sagamihara National Hospital

- Kochi Medical School Hospital

- Nagoya City University Hospital

- Dokkyo Medical University Hospital

- Iwasaki Clinic

- Kinki Hokuriku Airway disease Conference

- Kuwait

- Kuwait University, Faculty of Medicine

- Al-Rashed Allergy center, Ministry of Health, Kuwait

- The Kuwait Foundation for the Advancement of Sciences

- Mexico

- Hospital Médica Sur, Mexico City

- Centro de Atención de Enfermedades Cardiopulmonares, Guadalajara

- ISSSTE Hospital Regional Lic. Adolfo López Mateos, Mexico City

- South Korea

- Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital

- Konkuk University Hospital

- Yeouido St. Mary’s Hospital

- Ulsan University Hospital

- Haeundae Paik Hospital

- Hallym University Chuncheon Sacred Heart Hospital

- Hanyang University Hospital

- Hallym University Kangdong Sacred Heart Hospital

- Saudi Arabia

- King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh

- King Abdul Aziz University, Jeddah

- Spain

- Hospital Lucus Augusti. Lugo. EOXI Lugo, Cervo e Monforte

- Hospital Universitario Son Espases, Palma de Mallorca

- Hospital Universitario de Cruces. Barakaldo, Bizkaia

- Hospital Sta Creu i Sant Pau. Barcelona

- University Hospital San Agustín. Avilés

- Hospital Bellvitge. Barcelona

- Hospital 12 de Octubre. Madrid

- Taiwan

- Taipei Veterans General Hospital

- Taipei Medical University, Shuang Ho Hospital

- China Medical University Hospital

- Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital

- United Arab Emirates

- Rashid Hospital, Dubai

- UK

- Belfast Health & Social Care Trust

- Royal Brompton and Harefield Hospitals, London

- Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust

- Barts Health NHS Trust

Funding Statement

This study was conducted by the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute (OPRI) Pte Ltd and was partially funded by Optimum Patient Care Global and AstraZeneca Ltd. No funding was received by the Observational & Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (OPRI) for its contribution.

Ethics Approval

This study was designed, implemented, and reported in compliance with the European Network Centres for Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance Code of Conduct (EMA 2014; EUPAS33582) and with all applicable local and international laws and regulation. Registration of the ISAR database with the European Union Electronic Register of Post-Authorization studies was also undertaken (ENCEPP/DSPP/23720). ISAR has ethical approval from the Anonymised Data Ethics Protocols and Transparency (ADEPT) committee (ADEPT0218). Governance was provided by The Anonymous Data Ethics Protocols and Transparency (ADEPT) committee (registration number: ADEPT0420). All data collection sites in the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR) have obtained regulatory agreement in compliance with specific data transfer laws, country-specific legislation, and relevant ethical boards and organizations.

Author Contributions

All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, or in all these areas; took part in drafting, revising or critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. The study was supervised by David B. Price.

Disclosure

Mohsen Sadatsafavi has received honoraria from AZ, BI, and GSK for purposes unrelated to the content of this manuscript and has received research funding from AZ and BI directly into his research account from AZ for unrelated projects.

Trung N. Tran is an employee of AstraZeneca. AstraZeneca is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry.

Nigel Chong Boon Wong reports grants from Optimum Patient Care Global, grants from AstraZeneca Ltd, during the conduct of the study.

Nasloon Ali was an employee of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute (OPRI) at the time this research was conducted. OPRI conducted this study in collaboration with Optimum Patient Care and AstraZeneca.

Con Ariti is an employee of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute (OPRI). OPRI conducted this study in collaboration with Optimum Patient Care and AstraZeneca.

Esther Garcia Gil was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this research was conducted. AstraZeneca is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry.

Anthony Newell was an employee of Optimum Patient Care (OPC) at the time this research was conducted. OPC is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry.

Marianna Alacqua was an employee of AstraZeneca at the time this research was conducted. AstraZeneca is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry.

Mona Al-Ahmad has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Novartis, and GlaxoSmithKline.

Alan Altraja has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Berlin-Chemie Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Norameda, Novartis, Orion, Sanofi, and Zentiva; personal fees from Teva, Shire Pharmaceuticals and CSL Behring, sponsorships from AstraZeneca, Berlin-Chemie Menarini, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, MSD, Norameda, Sanofi, and Novartis; and has been a member of advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, and Teva.

Riyad Al-Lehebi has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, and Sanofi, reports personal fees from Novartis and participated in advisory board fees from GlaxoSmithKline.

Mohit Bhutani: has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Sanofi Genzyme, Covis pharmaceuticals; has been an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi Genzyme, Boehringer Ingelheim

Leif Bjermer has (in the last three years) received lecture or advisory board fees from Alk-Abello, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, Novartis, Sanofi, Genzyme/Regeneron, and Teva.

Anne-Sofie Bjerrum has received lecture fees from Astra Zeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis.

Arnaud Bourdin has received industry-sponsored grants from AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Cephalon/Teva, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi-Regeneron and consultancies with AstraZeneca-MedImmune, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Regeneron-Sanofi, Med-in-Cell, Actelion, Merck, Roche, and Chiesi.

Lakmini Bulathsinhala is an employee of the Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute (OPRI). OPRI conducted this study in collaboration with Optimum Patient Care and AstraZeneca.

Anna von Bülow reports speakers fees and consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, GSK and Novartis, outside the submitted work. She has also attended advisory board for Novartis and AstraZeneca.

John Busby reports personal fees from NuvoAir, outside the submitted work.

Giorgio Walter Canonica has received research grants, as well as lecture or advisory board fees from A. Menarini, Alk-Albello, Allergy Therapeutics, Anallergo, AstraZeneca, MedImmune, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi Farmaceutici, Circassia, Danone, Faes, Genentech, Guidotti Malesci, GlaxoSmithKline, Hal Allergy, Merck, MSD, Mundipharma, Novartis, Orion, Sanofi Aventis, Sanofi, Genzyme/Regeneron, Stallergenes, UCB Pharma, Uriach Pharma, Teva, Thermo Fisher, and Valeas.

Victoria Carter is an employee of Optimum Patient Care, a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry and reports grants from Optimum Patient Care Global, during the conduct of the study

Borja G. Cosio declares grants from Chiesi, AstraZeneca, Menarini, Teva and GSK; personal fees for advisory board activities from Chiesi, GSK, Novartis, Sanofi, Menarini, Teva and AstraZeneca; and payment for lectures/speaking engagements from Chiesi, Novartis, GSK, Menarini, Sanofi, Teva and AstraZeneca, outside the submitted work.

Richard W. Costello has received honoraria for lectures from Aerogen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Teva. He is a member of advisory boards for GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis, has received grant support from GlaxoSmithKline and Aerogen, has received personal fees from Respirasense, personal fees from PfizerBioNTech, during the conduct of the study and has patents in the use of acoustics in the diagnosis of lung disease, assessment of adherence and prediction of exacerbations, issued to 212.

J. Mark FitzGerald reports grants from AstraZeneca, GSK, Sanofi Regeneron, Novartis paid directly to UBC. Personal fees for lectures and attending advisory boards: AstraZeneca, GSK, Sanofi Regeneron, TEVA.

João A Fonseca reports grants from or research agreements with AstraZeneca, Mundipharma, Sanofi Regeneron and Novartis. Personal fees for lectures and attending advisory boards: AstraZeneca, GSK, Mundipharma, Novartis, Sanofi Regeneron and TEVA.

Liam G. Heaney declares he has received grant funding, participated in advisory boards and given lectures at meetings supported by Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Circassia, Evelo Biosciences, Hoffmann la Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Theravance and Teva; he has taken part in asthma clinical trials sponsored by Boehringer Ingelheim, Hoffmann la Roche, and GlaxoSmithKline for which his institution received remuneration; he is the Academic Lead for the Medical Research Council Stratified Medicine UK Consortium in Severe Asthma which involves industrial partnerships with a number of pharmaceutical companies including Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann la Roche, and Janssen.

Enrico Heffler participates in speaking activities and industry advisory committees for AstraZeneca, Sanofi-Genzyme, GSK, Novartis, Regeneron, Stallergenes-Greer, TEVA, Circassia and Nestlè Purina, grants from AstraZeneca and GSK

Mark Hew declares grants and other advisory board fees (made to his institutional employer) from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Sanofi, and Seqirus, for unrelated projects.

Flavia Hoyte declares honoraria from AstraZeneca. She has been an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Teva, Sanofi and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), for which her institution has received funding.

Takashi Iwanaga declares grants from Astellas, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Kyorin, MeijiSeika Pharma, Teijin Pharma, Ono, and Taiho, and lecture fees from Kyorin, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi and AstraZeneca.

David J. Jackson has received advisory board and speaker fees from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, Teva, Napp, Chiesi, Sanofi Regeneron, Novartis and research grant funding from AstraZeneca.

Rupert C. Jones declares grants from Astra Zeneca, Glaxo Smith Kline, Novartis OPRI and Teva and personal fees for consultancy, speakers’ fees or travel support from Astra Zeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Glaxo Smith Kline, Novartis and OPRI.

Mariko Siyue Koh reports grant support from AstraZeneca, and honoraria for lectures and advisory board meetings paid to her hospital (Singapore General Hospital) from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Sanofi and Boehringer Ingelheim, outside the submitted work.

Piotr Kuna reports personal fees from Adamed, personal fees from AstraZeneca, personal fees from Berlin Chemie Manarini, personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, personal fees from Lekam, personal fees from Novartis, personal fees from Chiesi, personal fees from Polpharma, personal fees from Sanofi, personal fees from Teva, personal fees from Zentiva, personal fees from FAES, personal fees from Glenmark, outside the submitted work

Désirée Larenas Linnemann reports speaker or personal fees from ALK, Alakos, Armstrong, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, DBV Technologies, Gossamer, Grunenthal, GSK, Mylan/Viatris, Menarini, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Purina institute, Sanofi, Siegfried, UCB, Carnot, Viatris, and grants from Sanofi, AbbVie, ALK, AstraZeneca, Circassia, Chiesi, GSK, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Purina Institute and UCB, outside the submitted work

Sverre Lehmann declares receipt of lecture (personal) and advisory board (to employer) fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novartis.

Lauri A. Lehtimäki declares personal fees for consultancy, lectures and attending advisory boards from ALK, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Circassia, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, Novartis, Orion Pharma, Sanofi, and Teva.

Juntao Lyu is an employee of Optimum Patient Care (OPC). OPC is a co-funder of the International Severe Asthma Registry.

Jorge Maspero reports grants and personal fees from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Novartis, and GSK, personal fees from IMMUNOTEK, personal fees from SANOFI, outside the submitted work.

Andrew N. Menzies-Gow has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi and Teva, andhas received speaker fees from AstraZeneca, Novartis, Teva and Sanofi. He has participated in research with AstraZeneca for which his institution has been remunerated and has attended international conferences with Teva. He has had consultancy agreements with AstraZeneca and Sanofi.

Nikolaos G. Papadopoulos declares research support from Gerolymatos, Menarini, Nutricia, and Vian; and consultancy/speaker fees from ASIT, AZ, Boehringer Ingelheim, GSK, HAL Allergy, Medscape, Menarini, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, and Nutricia, OM Pharma, Sanofi, and Takeda, grant from Capricare.

Andriana I. Papaioannou has received fees and honoraria from Menarini, GSK, Novartis, Elpen, Boehringer Ingelheim, AstraZeneca, and Chiesi.

Luis Perez-de-Llano declares non-financial support, personal fees, and grants from Teva, Sanofi and AstraZeneca, Chesi; non-financial support and personal fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Esteve, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, and Novartis; personal fees from MSD, TECHDOW PHARMA, Leo-Pharma, GEBRO and GILEAD; non-financial support from Menairi, grants, non-financial support from FAES during the conduct of the study.

Diahn-Warng Perng (Steve) received sponsorship to attend or speak at international meetings, honoraria for lecturing or attending advisory boards, and research grants from the following companies: AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, Daiichi Sankyo, Shionogi and Orient Pharma

Matthew Peters declares personal fees and non-financial support from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline.

Paul E. Pfeffer has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Sanofi and GSK; has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi and Novartis, for which his institution received remuneration; non-financial support from Chiesi; and has a current research grant funded by GlaxoSmithKline.

Celeste M. Porsbjerg has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, Novartis, TEVA, and Sanofi-Genzyme; has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca, Novartis, TEVA, Sanofi-Genzyme, and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, Novartis, MSD, Sanofi-Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis; and has received educational and research grants from AstraZeneca, Novartis, TEVA, GlaxoSmithKline, ALK, and Sanofi-Genzyme.

Todor A. Popov declares relevant research support from Novartis and Chiesi Pharma.

Chin Kook Rhee declares consultancy and lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Mundipharma, MSD, Novartis, Sandoz, Sanofi, Takeda, and Teva-Handok.

Sundeep Salvi declares research support and speaker fees from Cipla, Glenmark, GSK

Camille Taillé has received lecture or advisory board fees and grants to her institution from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, GlaxoSmithKline, Chiesi and Novartis, for unrelated projects.

Carlos A. Torres-Duque has received fees as advisory board participant and/or speaker from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and Sanofi-Aventis; has taken part in clinical trials from AstraZeneca, Novartis and Sanofi-Aventis; has received unrestricted grants for investigator-initiated studies at Fundacion Neumologica Colombiana from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline, Grifols and Novartis.

Charlotte S. Ulrik has attended advisory boards for AstraZeneca, ALK-Abello, GSK, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, Chiesi, TEVA, and Sanofi-Genzyme; has given lectures at meetings supported by AstraZeneca, Sandoz, Mundipharma, Chiesi, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Orion Pharma, Novartis, TEVA, Sanofi-Genzyme, and GlaxoSmithKline; has taken part in clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, Novartis, Merck, InsMed, ALK-Abello, Sanofi-Genzyme, GlaxoSmithKline, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Regeneron, Chiesi and Novartis; and has received educational and research grants from AstraZeneca, MundiPharma, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, TEVA, GlaxoSmithKline and Sanofi-Genzyme; has received personal fees from Pfizer.

Seung Won Ra has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, and Novartis.

Eileen Wang has received honoraria from AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Wefight, and Clinical Care Options. She has been an investigator on clinical trials sponsored by AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Genentech, Novartis, Teva, and Sanofi, for which her institution has received funding. She has received personal fees from Wefight.

Michael E. Wechsler reports receiving consulting honoraria from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Genentech, GSK, Novartis, Regeneron, Sanofi and Teva; personal fees from Amgen, Avalo, Cerecor, Cytoreason, Eli Lilly, Equillium, Incyte, Kinaset, Phylaxis, Pulmatrix, Rapt and Sound Biologics.

David B. Price has advisory board membership with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Thermofisher; consultancy agreements with Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, GlaxoSmithKline, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theravance; grants and unrestricted funding for investigator-initiated studies (conducted through Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd) from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Circassia, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Respiratory Effectiveness Group, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals, Theravance, UK National Health Service; payment for lectures/speaking engagements from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Cipla, GlaxoSmithKline, Kyorin, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi Genzyme, Teva Pharmaceuticals; payment for the development of educational materials from Mundipharma, Novartis; payment for travel/accommodation/meeting expenses from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Mundipharma, Mylan, Novartis, Thermofisher; funding for patient enrolment or completion of research from Novartis; stock/stock options from AKL Research and Development Ltd which produces phytopharmaceuticals; owns 74% of the social enterprise Optimum Patient Care Ltd (Australia and UK) and 74% of Observational and Pragmatic Research Institute Pte Ltd (Singapore); 5% shareholding in Timestamp which develops adherence monitoring technology; is peer reviewer for grant committees of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme, and Health Technology Assessment; and was an expert witness for GlaxoSmithKline. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED., et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:59–99. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200801-060ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luskin AT, Antonova EN, Broder MS, et al. Health care resource use and costs associated with possible side effects of high oral corticosteroid use in asthma: a claims-based analysis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2016;8:641–648. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S115025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canonica GW, Colombo GL, Bruno GM, et al. Shadow cost of oral corticosteroids-related adverse events: a pharmacoeconomic evaluation applied to real-life data from the Severe Asthma Network in Italy (SANI) registry. World Allergy Org J. 2019;12:100007. doi: 10.1016/j.waojou.2018.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, et al. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy. 2018;11:193–204. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S176026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sweeney J, Patterson CC, Menzies-Gow A, et al. Comorbidity in severe asthma requiring systemic corticosteroid therapy: cross-sectional data from the Optimum Patient Care Research Database and the British Thoracic Difficult Asthma Registry. Thorax. 2016;71:339–346. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fardet L, Petersen I, Nazareth I. Prevalence of long-term oral glucocorticoid prescriptions in the UK over the past 20 years. Rheumatology. 2011;50:1982–1990. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ker017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tran TN, King E, Sarkar R, et al. Oral Corticosteroid Prescription Patterns for Asthma in France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. Eur Respir J. 2020. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02363-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tran TN, MacLachlan S, Hicks W, et al. Oral Corticosteroid Treatment Patterns of Patients in the United States with Persistent Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:338–346.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bleecker ER, Menzies-Gow AN, Price DB, et al. Systematic Literature Review of Systemic Corticosteroid Use for Asthma Management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:276–293. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201904-0903SO [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Voorham J, Xu X, Price DB, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with incremental systemic corticosteroid exposure in asthma. Allergy. 2019;74:273–283. doi: 10.1111/all.13556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang E, Wechsler ME, Tran TN, et al. Characterization of Severe Asthma Worldwide: data From the International Severe Asthma Registry. Chest. 2020;157:790–804. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2019.10.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agache I, Beltran J, Akdis C, et al. Efficacy and safety of treatment with biologicals (benralizumab, dupilumab, mepolizumab, omalizumab and reslizumab) for severe eosinophilic asthma. A systematic review for the EAACI Guidelines - recommendations on the use of biologicals in severe asthma. Allergy. 2020;75:1023–1042. doi: 10.1111/all.14221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krings JG, McGregor MC, Bacharier LB, et al. Biologics for Severe Asthma: treatment-Specific Effects Are Important in Choosing a Specific Agent. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;7:1379–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Porsbjerg CM, Menzies-Gow AN, Tran TN, et al. Global Variability in Administrative Approval Prescription Criteria for Biologic Therapy in Severe Asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2022;10:1202–1216. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.12.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown T, Jones T, Gove K, et al. Randomised controlled trials in severe asthma: selection by phenotype or stereotype. Eur Respir J. 2018:52. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01444-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.FitzGerald JM, Tran TN, Alacqua M, et al. International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR): protocol for a global registry. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2020;20(1):212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bulathsinhala L, Eleangovan N, Heaney LG, et al. Development of the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR): a Modified Delphi Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:578–588.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.08.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ISAR Study Group. International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR): mission Statement. Chest. 2020;157:805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang E, Wechsler ME, Tran TN, et al. Characterization of severe asthma worldwide: data from the International Severe Asthma Registry (ISAR). Chest. 2020;157:805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; 2018. Available from: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINAL-revised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2022.

- 21.Heaney LG. Eosinophilic and Noneosinophilic Asthma: an Expert Consensus Framework to Characterize Phenotypes in a Global Real-Life Severe Asthma Cohort. CHEST. 2021. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Statistical Soc Series B. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reddel HK, Bacharier LB, Bateman ED, et al. Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) Strategy 2021 - Executive summary and rationale for key changes. Eur Respir J. 2021. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02730-2021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Inselman JW, Jeffery MM, Maddux JT, et al. Trends and Disparities in Asthma Biologic Use in the United States. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:549–554.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bel EH, Wenzel SE, Thompson PJ, et al. Oral Glucocorticoid-Sparing Effect of Mepolizumab in Eosinophilic Asthma. N Eng J Med. 2014;371:1189–1197. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nair P, Wenzel S, Rabe KF, et al. Oral Glucocorticoid–Sparing Effect of Benralizumab in Severe Asthma. N Eng J Med. 2017;376:2448–2458. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1703501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rabe KF, Nair P, Brusselle G, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dupilumab in Glucocorticoid-Dependent Severe Asthma. N Eng J Med. 2018;378:2475–2485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1804093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.FitzGerald JM, Bleecker ER, Nair P, et al. Benralizumab, an anti-interleukin-5 receptor α monoclonal antibody, as add-on treatment for patients with severe, uncontrolled, eosinophilic asthma (CALIMA): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled Phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2016;388:2128–2141. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Castro M, Zangrilli J, Wechsler ME, et al. Reslizumab for inadequately controlled asthma with elevated blood eosinophil counts: results from two multicentre, parallel, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651–659. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson DJ, Busby J, Pfeffer PE, et al. Characterisation of patients with severe asthma in the UK Severe Asthma Registry in the biologic era. Thorax. 2021;76:220–227. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ortega H, Gleich G, Mayer B, et al. Reproducibility of a Single Blood Eosinophil Measurement as a Biomarker in Severe Eosinophilic Asthma. Annals ATS. 2015;12:1896–1897. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201507-443LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tinoco EM, Gigante AR, Fernandes AL, et al. Impact of biologic therapy in severe asthma with nasal polyps. Eur Respir J. 2021:58. doi: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2021.PA3739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bachert C, Han JK, Desrosiers M, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in patients with severe chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps (LIBERTY NP SINUS-24 and LIBERTY NP SINUS-52): results from two multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trials. Lancet. 2019;394:1638–1650. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rogliani P, Calzetta L, Matera MG, et al. Severe Asthma and Biological Therapy: when, Which, and for Whom. Pulm Ther. 2020;6:47–66. doi: 10.1007/s41030-019-00109-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matera MG, Calzetta L, Sanduzzi A, et al. Effects of neuraminidase on equine isolated bronchi. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2008;21:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.d’Ancona G, Kavanagh J, Roxas C, et al. Adherence to Inhaled Corticosteroids and Clinical Outcomes in Mepolizumab Therapy for Severe Asthma. Eur Respir J. 2020. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02259-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alahmadi FH, Simpson AJ, Gomez C, et al. Medication Adherence in Patients With Severe Asthma Prescribed Oral Corticosteroids in the U-BIOPRED Cohort. Chest. 2021;160:53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.02.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tiotiu A. Applying personalized medicine to adult severe asthma. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2021;42:e8–16. doi: 10.2500/aap.2021.42.200100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taillé C, Devillier P, Dusser D, et al. Evaluating response to biologics in severe asthma: precision or guesstimation? Respir Med Res. 2021;80:100813. doi: 10.1016/j.resmer.2021.100813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bossios A. Inflammatory T2 Biomarkers in Severe Asthma Patients: the First Step to Precision Medicine. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9:2689–2690. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2021.04.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]