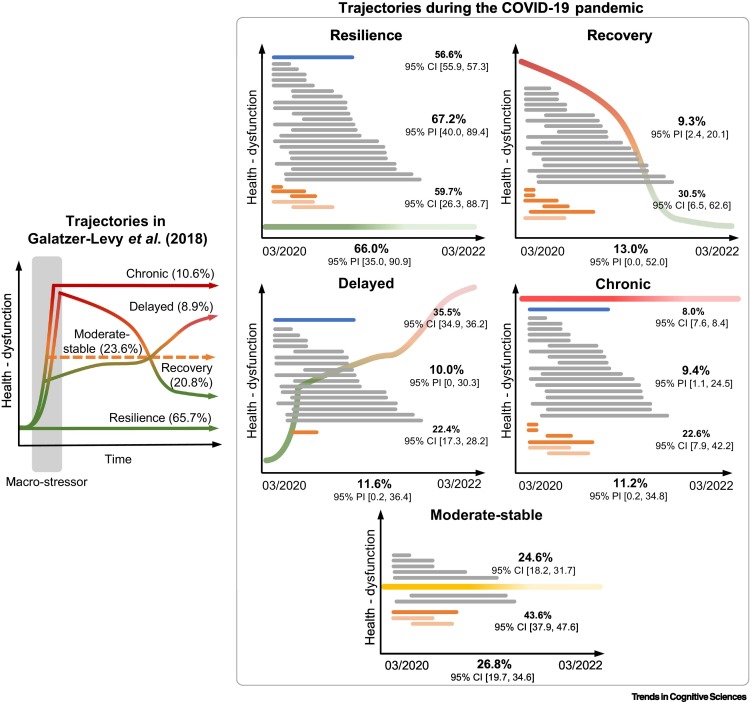

Figure 1.

Trajectories across 28 observational studies conducting trajectory modeling.

This figure schematically illustrates trajectories of mental distress identified during the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic (right panels) and trajectories identified by Galatzer-Levy et al. [31] based on a meta-analysis of 54 studies on individual-level macro-stressors (left panel; 67 samples, 2004–2016). Percentages reported in the right panel in the middle of each x-axis are meta-analytical estimates based on 28 pandemic-related studies performing growth mixture modeling. Lines in the right panels schematically illustrate the peri-pandemic observational periods covered by each study. Gray lines refer to middle-aged adult samples, orange lines to young adult samples, and blue lines to the study on older adults [79], with the respective prevalence estimates along with prediction intervals (for middle-aged adults) and confidence intervals (for younger and older adults) being presented at the same height. For all trajectories, heterogeneity was considerable, which is comparable to the results reported in the review by Galatzer-Levy et al. [31]. Moreover, the wide prediction intervals point to the fact that one cannot precisely infer from the current findings on prevalence rates in future studies from similar populations. In line with the previous review [31], our meta-analytical summary estimated the prevalence per trajectory among those studies that identified the respective trajectory; thus, prevalence does not need to sum up to 100, but instead represents prevalence means across studies finding the respective trajectory. Details on our method can be found in our Technical Report [47].