Figure 1.

Task, experimental design, behavioral results, and group EEG encoding pattern

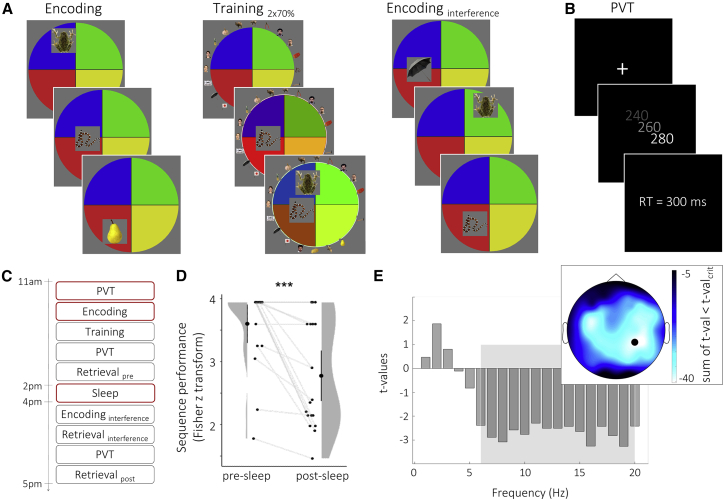

(A) Memory Arena. During encoding, 20 objects were presented in a specific sequence at different spatial positions. Both sequence and spatial position had to be encoded. Training (and retrieval) started with all 20 objects arranged around the arena, and participants had to drag and drop the objects in the correct sequence to the correct spatial position. During training, feedback was given after each trial and errors were corrected. Training was completed after reaching a performance criterion of 70% twice in a row. Retroactive interference was induced by encoding the same objects but in a different sequence and at different spatial positions.

(B) Every trial of the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT) started with a fixation cross. After a delay of 10–15 s, a counter started. Participants had to press the space bar as fast as possible and received feedback about their reaction time (RT).

(C) Participants performed the PVT, encoding, training, and first retrieval before the 2-h nap. After the nap, an interference session was employed (1× encoding and retrieval, no training), followed by the second retrieval of the originally learned arena. For EEG data analyses, the first PVT, encoding, and sleep data were used.

(D) Sequence memory significantly decreased from pre- to post-sleep. Single participant data, density plots, and group means with 95% CIs are shown. ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

(E) Comparison of oscillatory power during Memory Arena versus PVT (thresholded at p < 0.05 cluster corrected), revealing a significant power decrease from 6–20 Hz during encoding (gray rectangle), most pronounced over temporo-parietal areas (bars shown for electrode CP4, black circle on topography plot; see Figures S1A and S1B for raw values).