Abstract

Alterations of mitochondrial and glycolytic energy pathways related to aging could contribute to cerebrovascular dysfunction. We studied the impact of aging on energetics of primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs) by comparing the young (passages 7–9), pre-senescent (passages 13–15), and senescent (passages 20–21) cells. Pre-senescent HBMECs displayed decreased telomere length and undetectable telomerase activity although markers of senescence were unaffected. Bioenergetics in HBMECs were determined by measuring the oxygen consumption (OCR) and extracellular acidification (ECAR) rates. Cellular ATP production in young HBMECs was predominantly dependent on glycolysis with glutamine as the preferred fuel for mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). In contrast, pre-senescent HBMECs displayed equal contribution to ATP production rate from glycolysis and OXPHOS with equal utilization of glutamine, glucose, and fatty acids as mitofuels. Compared to young, pre-senescent HBMECs showed a lower overall ATP production rate that was characterized by diminished contribution from glycolysis. Impairments of glycolysis displayed by pre-senescent cells included reduced basal glycolysis, compensatory glycolysis, and non-glycolytic acidification. Furthermore, impairments of mitochondrial respiration in pre-senescent cells involved the reduction of maximal respiration and spare respiratory capacity but intact basal and ATP production-related OCR. Proton leak and non-mitochondrial respiration, however, were unchanged in the pre-senescent HBMECs. HBMECS at passages 20–21 displayed expression of senescence markers and continued similar defects in glycolysis and worsened OXPHOS. Thus, for the first time, we characterized the bioenergetics of pre-senescent HBMECs comprehensively to identify the alterations of the energy pathways that could contribute to aging.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11357-022-00550-2.

Keywords: Oxygen consumption rate, Oxidative phosphorylation, Glycolysis, Extracellular acidification rate, ATP

Introduction

Brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMECs) play a critical role in maintaining brain function by regulating the blood flow, blood–brain-barrier (BBB) integrity, and neurovascular coupling (NVC) function. Aging impairs the function of BMECs, leading to impaired NVC and BBB [1, 2], thereby increasing the risk of stroke, cognitive dysfunction, and neurodegenerative diseases [3].

Maintenance of BBB integrity and NVC function are energy-demanding processes. Glycolysis and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) are the major energy-generating pathways in the eukaryotic cells. Previous studies have shown that endothelial cells are highly glycolytic despite existing in a high oxygen environment [4–6]. Furthermore, glycolysis has been shown to regulate proliferation, migration, and vessel sprouting [5, 6]. Despite the conflicting views about the contribution of mitochondria to endothelial cell energy, unequivocal evidence supports the critical role of mitochondria in cellular signaling [7]. Interestingly, brain endothelial cells contain double the number of mitochondria compared to the other endothelial cell types [8], and energy demands such as for the maintenance of BBB are unique to brain endothelial cells. However, the relative contributions of glycolysis and OXPHOS toward BMEC energy have not been assessed previously [9–12]. To date, no study has characterized the microvascular bioenergetics or evaluated the impact of aging on the bioenergetics in BMECs. In vitro, cultured cells from low- and high-passage numbers are often used to study the early and late changes of cells representing aging [13]. The present study attempts to validate the use of cell passages as a model of aging and examine the temporal changes in bioenergetics in pre-senescence and senescence.

Considering the unique role of energy metabolism in endothelial function, we characterized the glycolytic and OXPHOS pathways of energy generation in cultured primary human BMECs (HBMECs) at early (7–9 passages; young) and pre-senescent stages (13–15 passages; pre-senescent). Specifically, we assessed: (I). the relative contribution of glycolysis and OXPHOS to ATP production in HBMECs; (ii). the basal and compensatory glycolytic rate; iii). the basal and maximal mitochondrial respiration and mitochondrial reserve capacity; (iv). the substrate preferences for energy generation. We also characterized the bioenergetics of the senescent HBMECs (passages 20–21). This is the first study to characterize the bioenergetics of BMECs from any species and investigate the impact of in vitro aging on the bioenergetics of pre-senescent and senescent brain endothelial cells. The value of employing cultured HBMECs is threefold: First, to our knowledge, there has been no report of cellular energetics in cerebral microvascular endothelial cells. Second, previous studies investigating the impact of aging on the bioenergetics employing cultured cells from low- and high-passage numbers have contributed significantly to our knowledge [13]. Third, the rationale for choosing cells from two passages separated by 6 passages was to identify the role of impaired energy metabolism before the onset of significant signs of senescence unlike the similar previous study [13]. Notably, we have carried out for the first time a comprehensive characterization of glycolytic and OXPHOS pathways by measuring the oxygen consumption rate (OCR) and extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) utilizing the Agilent Seahorse XFe24 analyzer.

Methods

Reagents

Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (23,227, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), NP40 lysis buffer (FNN0021, Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), protease inhibitor cocktail (P8340, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO), phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (P0044, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO).

Seahorse Analyzer reagents

The following reagents were purchased from Agilent Technologies (Santa Clara, CA). XFe24 Flux Pak (102,340–100), Seahorse XF RPMI media (103,576–100), Seahorse XF Real-Time ATP Rate Assay kit (103,592–100), Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test kit (103,015,100), Seahorse XF Glycolytic Rate Assay kit (103,344–100), Seahorse XF Mito Fuel Flex Test kit (103,260–100). Sodium pyruvate (P8574, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO), d-( +)-glucose (G7528, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO), L-Glutamine (25,030,081, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Human Brain Microvascular endothelial cells (HBMECs)

Primary HBMECs purchased from Cell Systems (Kirkland, WA) were isolated from the healthy male donor and were grown, passaged in the complete classic media (4ZO-500, Cell Systems, Kirkland, WA) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. These cells are not genetically modified to induce the transformation. This media is based on modified basal DMEM/F12 (1:1) media containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 15.8 mM glucose, and do not contain the pH indicator, phenol red. After reaching the confluence (90–95%), cells were passaged to the seahorse cell culture plates (60,000 cells/well) and the seahorse experiments were conducted after the twenty hours (95–100% confluency). Passage numbers 7–9 were taken as young (low-passage), and passage numbers 13–15 were taken as pre-senescent (high-passage) cells. For each experiment, at least a 6–8 passage difference was maintained between the young and the pre-senescent cells. Pre-senescent cells were confirmed by lack of senescent markers and negligible β-galactosidase positive cells but differed by shortened telomeres and negligible telomerase activity when compared to the young HBMECs, confirming the in-vitro aging. We observed a significant rise in senescent cells in passage 20 and after by β-galactosidase staining and thus we considered HBECs after passage 20 as senescent cells.

Telomere Length and Telomerase activity

HBMECs at p8 and p15 were analyzed for telomere length and the telomerase activity using Relative Human Telomere Length Quantification qPCR Assay and Telomerase Activity Quantification qPCR Assay Kits, respectively (8908 & 8928, ScienCell, Carlsbad, CA). For, telomere length, genomic DNA was isolated from HBMECs grown in 60-mm cell culture dishes using DNAzol reagent (10,503,027, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA). 10 ng genomic DNA was taken from each sample and quantitative PCR was performed and fold changes were calculated as per the manufacturer’s instructions. For telomerase activity, HBMECs were lysed as per the protocol, and protein was measured using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA). Cell lysate (1 µg) was taken incubated with telomerase assay buffer in a final volume of 20 µL for 3 h at 37 °C. Later, the samples were heat-inactivated and 1 µL of the telomerase-treated cell lysate was taken and the quantitative PCR was performed. Threshold cycle (Ct) value less than 33 was taken a detectable telomerase activity and Ct value above 33 was taken as undetectable telomerase activity.

Senescence markers

The β-galactosidase activity was detected in the HBMECs using Mammalian β-Galactosidase Assay Kit (75,707, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and the staining for the β-galactosidase activity was performed using senescence β-galactosidase staining kit (9860, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA). 100X images were taken after the eight-to-twelve-hour incubation with the reagent (OMAX A35140U microscope). The assays were performed as per the manufacturer’s protocols. Further, P21 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1) was detected in the HBECs using immunofluorescence. Briefly, HBMECs were grown on coverslips, washed with PBS, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature (RT). Later the cells were washed with PBST three times and blocked with 2% BSA in PBST for an hour at RT and incubated with protein P21 primary antibody overnight at 4 °C (1 µg/mL, 407,722, Novus Biologicals, Centennial, CO). Later the cells were washed with PBST followed by incubation with Alexa-488 tagged goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:1000 dilution, A11029, Thermo Scientific). Images (200X) were taken using EVOS FL fluorescent microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Senescence marker gene expression was quantified using Taqman assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific). RNA was isolated from the HBMEC using Trizol and the expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1a (P21, CDKN1A, Hs00355782_m1), Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7, Hs00266026_m1), Checkpoint Kinase 2 (CHEK2, Hs00200485_m1), High Mobility Group Box 1 (Hmgb1, Hs01923466_g1), serine–arginine splicing factor 1 (Srsf1, Hs04185403_g1). Hydroxymethylbilane Synthase (Hmbs, Hs00609300_g1) gene is used as the housekeeping gene.

Analysis of Cellular Energetics

Cellular energetics of HBMECs were determined by adapting the protocol we first reported for brain microvessels containing mostly capillary endothelial cells [14]. Young and pre-senescent HBMECs were grown on the same 24 well plate. For all the experiments, a 6 to 8 passage difference was maintained between the young and pre-senescent cells. Bioenergetics were determined using a seahorse XFe24 analyzer. Glycolytic and OXPHOS parameters were determined using Seahorse XF Glycolytic Rate Assay kit and XF Cell Mito Stress Test kit, respectively. ATP production rates and relative contribution from the glycolysis and the OXPHOS were measured by the Seahorse XF Real-Time ATP Rate Assay kit. Mitochondrial fuel dependence was investigated using the Seahorse XF Mito Fuel Flex Test kit.

Real-time ATP Rate Assay

ATP production rates and the relative contributions of glycolysis and OXPHOS were measured using a Real-Time ATP Rate Assay. Cells were incubated with seahorse RPMI media (pH 7.4) containing 25 mmol/L glucose, 10 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 2 mmol/L glutamine (pH 7.4) for an hour at 37 0C in a non-CO2 incubator. OCR and ECAR were measured before and after the treatment with oligomycin (2 µmol/L each) followed by rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 µmmol/L each). Glycolysis-derived ATP (glycoATP) production rate, mitochondria-derived ATP (mitoATP) production rate, and total ATP production rate were measured along with the ATP rate index (mitoATP/glycoATP production rate), percentage of glycolysis, and OXPHOS using Wave 2.6.1 software. GlycoATP and mitoATP production rates were expressed as picomoles of ATP/min and were defined as the ATP production associated with the conversion of glucose to lactate (glycolysis) and oxidative phosphorylation, respectively. Total ATP production rates were the sum of the glycoATP and mitoATP production rates. ATP rate index is the ratio between the mitoATP production rate and glycoATP production rate and indicates the metabolic state of the cell.

GlycoATP production rates were measured based on the following stoichiometric equation:

Glucose + 2 ADP + 2 Pi 2 Lactate + 2 ATP + 2 H2O + 2 H+

The rate of proton production due to glycolysis (glycolysis-associated proton efflux rate, GlycoPER) is equal to the glycoATP production rate as for each molecule glucose converted to lactate, two molecules of ATP and two protons were released.

GlycoATP production rate (picomoles of ATP/min) = GlycoPER (picomoles of H+/min).

GlycoPER is calculated from the ECAR and is described in detail in the glycolysis rate assay.

MitoATP production rate is calculated from the OCR before and after the addition of oligomycin (inhibition of ATP synthase, oligo OCR).

OCR ATP (picomoles of O2/min) = Basal OCR – Oligo OCR.

Basal OCR and oligo OCR were calculated after deducting the OCR due to non-mitochondrial respiration (after the addition of antimycin/rotenone).

Calculation of mitoATP production rate from OCR ATP involves the following equations.

C6H12O6 + 6O2 6CO2 + 6H2O + 33 ATP.

The P/O ratio indicates the generation of the number of ATP molecules for a single oxygen atom consumed, i.e., 2.75 calculated under ideal seahorse assay conditions.

MitoATP Production rate (picomoles of ATP/min) = OCR ATP (picomoles of O2/min) × 2 (number of oxygen atoms) × 2.75 (P/O ratio).

The final total ATP production rate of given cells or tissue is calculated as the sum of the mitoATP and glycoATP production rates.

Glycolysis Rate Assay

Glycolytic parameters were measured in the young and the aged HBMECs in the Seahorse XFe24 analyzer using a Glycolytic Rate Assay kit. Cells were incubated with seahorse RPMI media (pH 7.4) containing 25 mmol/L glucose, 10 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 2 mmol/L glutamine (pH 7.4) for an hour at 37 0C in the non-CO2 incubator. ECAR and OCR were measured before and after the injection of rotenone and antimycin combination (0.5 µmol/L each) followed by 50 mmol/L of 2-deoxyglucose (2-DG). Data analysis was performed using the Seahorse Wave Software (Wave 2.6.1, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Parameters like basal glycolysis, induced glycolysis, basal PER, and %PER from glycolysis were measured along with mitoOCR/glycoPER and post 2DG-acidification.

Real-time glycolysis rates were obtained by measuring OCR and ECAR before and after the sequential addition of the rotenone and antimycin mixture and the 2-DG. The principle involved in this assay is that protons secreted into the media (proton efflux rate) are majorly due to the lactate production, i.e., glycolytic activity of the cells. The proton efflux rate (PER) is calculated from the ECAR using the following equation:

PER (pmol H+/min) = ECAR (mpH/min) × buffer factor (mmol/L/pH) × Geometric Volume (µL) × volume scaling factor (Kvol).

Geometric volume and scaling factor are related to the microchamber created surrounding the cells by the seahorse sensors to measure ECARs and OCRs.

PER from given cells or tissue is the sum of the protons from glycolysis-derived lactate, mitochondrial OXPHOS-derived CO2, and other proton-secreting pathways.

Total PER = PER from the lactate (glycolysis) + PER from the CO2 (OXPHOS) + PER from the other pathways.

Basal PER is considered the sum of the PER due to glycolysis (glycoPER) and other non-glycolytic sources.

Basal PER = GlycoPER + PER from non-glycolytic sources.

OXPHOS contribution to the PER changes was calculated from the OCR drop after the antimycin and rotenone injection (A/R), as OCR stoichiometrically equals to CO2 release, which is in turn equal to the proton efflux rate.

Basal PER = total PER—(basal OCR – OCR after A/R).

The addition of 2-DG results in inhibition of glycolysis and hence the residual PER observed after the 2-DG treatment is from the non-glycolytic sources.

GlycoPER = Basal PER – post 2-DG PER.

GlycoPER (picomoles of H+/min) is highly correlated with cellular glycolytic activity. Basal glycolysis is calculated by multiplying glycoPER by the correlation factor.

The addition of the antimycin/rotenone mixture not only helps to measure PER due to OXPHOS but also to measure compensatory glycolysis. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration results in a shift of energy metabolism toward glycolysis, as cells completely depend on glycolysis for the energy demands. Compensatory glycolysis indicates the maximal cellular glycolytic capacity. The ratio between the mitoOCR/glycoPER indicates the metabolic state of the cells, i.e., dependency on the glycolysis or OXPHOS.

Cell Mito Stress Test

Various mitochondrial respiratory parameters were determined using the Cell Mito Stress Test kit. Cells were incubated in seahorse RPMI media (pH 7.4) containing 25 mmol/L glucose, 10 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 2 mmol/L glutamine (pH 7.4) for an hour at 37 0C in a non-CO2 incubator. Later cells were sequentially exposed to Oligomycin (2 µmol/L), followed by FCCP (1.1 µmol/L) and rotenone/antimycin A (0.5 µmol/L). Oxygen consumption rates (OCRs) were measured and parameters like basal respiration, ATP production, maximal respiration, and spare respiratory capacity were measured along with the proton leak, and the non-mitochondrial respiration was calculated using Wave 2.6.1 software. Although OCR is predominantly due to mitochondrial respiration, other oxygen-consuming metabolic reactions (non-mitochondrial respiratory OCR) exist in cells. Thus, residual OCR after the antimycin/rotenone treatment is considered as the non-mitochondrial respiratory OCR. Basal respiration represents the mitochondrial OCR in the given microenvironment and indicates basic mitochondrial energy needs.

Basal respiration (picomoles of O2/min) = Basal OCR- OCR (A/R).

OCR-linked to the ATP production from the OXPHOS is calculated from the change in the OCR after inhibition of ATP synthase with oligomycin treatment.

ATP Production (picomoles of O2/min) = (Basal OCR - OCR Oligo) – OCR (A/R).

FCCP, the OXPHOS uncoupler, increases the permeability of the inner mitochondrial membrane for protons resulting in decreased proton gradient and membrane potential. Mitochondrial respiration was maximized to normalize the membrane potential. The OCR after the FCCP treatment represents the maximal mitochondrial respiratory capacity of the cell.

Maximal Respiration (picomoles of O2/min) = OCR (FCCP)—OCR (A/R).

Spare respiratory capacity measures the cellular ability to elevate the mitochondrial respiration in response to the energy demand and is calculated from the basal and maximal respiration.

Spare Respiratory Capacity (picomoles of O2/min) = Maximal respiration – basal respiration.

Though most of the protons transported to inner mitochondrial space due to electron transport chain activity move back to the matrix through ATP synthase, some of the protons are leaked through the damaged mitochondrial membrane or specialized proton transporting proteins. Proton leak is the measure of proton transport independent of ATP synthase and was calculated from the OCR after ATP synthase inhibition (oligomycin) and OCR after complete inhibition of mitochondrial respiration (antimycin/rotenone).

Proton Leak (picomoles of O2/min) = OCR (oligo) – OCR (A/R).

Mito Fuel Flex Test

Mitochondrial fuel preferences of the HBMECs were measured using the Mito Fuel Flex Test kit. Cells were incubated in seahorse RPMI media (pH 7.4) containing 25 mmol/L glucose, 10 mmol/L sodium pyruvate, and 2 mmol/L glutamine (pH 7.4) for an hour at 37 0C in a non-CO2 incubator. OCRs were measured after the pharmacological inhibition of glutaminase (3 µmol/L BPTES), mitochondrial fatty acid transport (4 µmol/L etomoxir), and pyruvate transport (2 µmol/L UK5099). The fuel dependency for each fuel was calculated as follows.

Dependency (%) = (Baseline OCR – Target Inhibitor OCR/Bassline OCR – all inhibitor OCR) × 100.

Statistics

Data were represented as the mean ± S.E. and analyzed by employing student t-test (normally distributed data) or Mann–Whitney test (skewed data) using the p-value ≤ 0.05 to determine the statistical significance (GraphPad prism 8.4.3; San Diego, CA). To establish the reproducibility of the data, experiments were performed a minimum of three times independently. Data from the independent replicates are presented in the supplementary materials.

Results

Pre-senescent HBMECs have reduced telomere length and telomerase activity.

Pre-senescent HBMECs have significantly reduced telomere length when compared to young cells (Fig. 1A). In addition, telomerase activity was undetectable in the pre-senescent HBMECs, whereas detectable telomerase activity was observed in the young cells (Fig. 1B). Interestingly, pre-senescent HBMECs failed to exhibit senescence markers including the significant presence of β-galactosidase positive cells, elevated P21 protein expression (Fig. 1C, D) and increased expression of marker genes CDKN1a, IGFBP7, CHEK2, Hmgb1, and Srsf1 (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Pre-senescent HBMECs from have reduced telomere length but lack senescence markers. Pre-senescent HBMECs (p15) displayed decreased telomere length (relative fold change; A) and undetectable telomerase activity (B) measured by qPCR-based methods compared to young cells (p7). Data were represented as mean ± S.E.M and analyzed by student’s t-test. ‘*’ indicate p ≤ 0.05. n = 4 replicates/phenotype. C) β- Galactosidase staining. HBECs were stained for β- Galactosidase activity using Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit (100X magnification). (D) P21 protein immunofluorescence. P21 protein is elevated in senescent cells. P21 was detected in HBMECs using immunofluorescence (P21 antibody, Novus biologicals & Alexa 488-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibody). P21 protein fluorescence was negligible in both p8 and p14 HBMECs (200X magnification). (E) Senescent gene expression. RNA was isolated from the HBMECs, and the senescent marker gene expression was quantified by Taqman probe assay. (i) cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 1a (CDKN1A) (ii). Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7). (iii). Checkpoint Kinase 2 (CHEK2). (iv). High Mobility Group Box 1 (Hmgb1). (v). serine–arginine splicing factor 1 (Srsf1). n = 3 replicates/phenotype. Hydroxymethylbilane Synthase (Hmbs) gene was used as the housekeeping gene

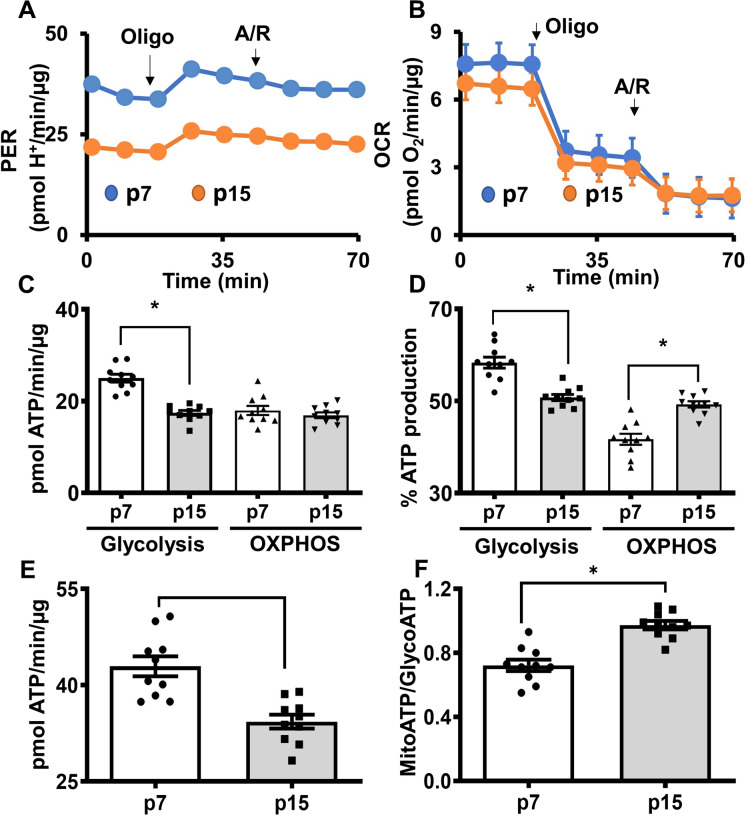

Pre-senescent HBMECs have reduced ATP production rates due to impaired glycolysis.

Real-time ATP rate assay measuring proton efflux rates (PER) and OCR revealed that pre-senescent cells have reduced total ATP production rates when compared with the young cells (Fig. 2A and 4B). In contrast, ATP production rates from glycolysis were reduced significantly in senescent HBMECs compared to the young cells (Fig. 2C). ATP production rates from OXPHOS were not altered between the young and pre-senescent HBMECs (Fig. 2C). Moreover, the percent ATP production derived from glycolysis was significantly decreased whereas the percent ATP production from OXPHOS was significantly higher in the pre-senescent cells when compared to the young cells. (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, pre-senescent HBMECs have reduced total ATP production rates when compared to the young cells indicating diminished energy production before the senescence (Fig. 2E). Similarly, the ATP rate index (the ratio of the mitoATP production rate divided by the glycoATP production rate) was increased in the pre-senescent cells, indicating that the contribution from OXPHOS toward total cellular energy was higher in the pre-senescent cells due to diminished glycolysis (Fig. 2F). These observations were highly reproducible and the data from the replicate experiments were provided in supplemental figures (Supplemental Figure S1-S3).

Fig. 2.

Total ATP production rates are lower in pre-senescent HBMECs due to diminished glycolysis. HBMECs from young (p7) and pre-senescent (p15) were analyzed for ATP rate production rates using Seahorse XF Real-Time ATP Rate Assay. Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) were measured before and after treatment of oligomycin (Oligo, 1 µmol/L), followed by treatment with antimycin/rotenone (A/R, 0.5 µmol/L each), and data were analyzed using Wave 2.6 software. (A). Proton efflux rate (PER). (B). OCR. (C). ATP production rates from glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS). (D). Percent ATP from glycolysis and OXPHOS. (E). Total ATP production rate. (F). ATP rate index (MitoATP/GlycoATP). Data were represented as mean ± S.E.M and analyzed by student’s t-test. ‘*’ indicate p ≤ 0.05. N = 9–10 wells per phenotype. It is noted that various parameters in the bar graphs were derived from the same raw ECAR and OCR data, thus, the relative distribution of data points may show some similarity. Experiments were repeated three times for reproducibility (data presented in the online supplementary materials)

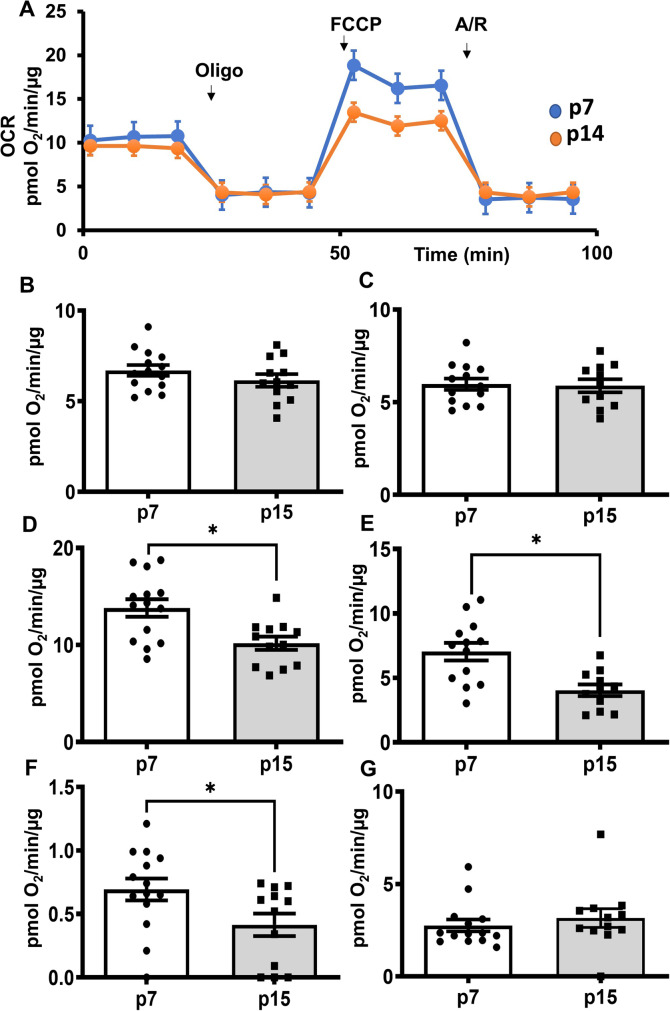

Fig. 4.

Mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity was reduced in the pre-senescent HBMECs. Young (p7) and pre-senescent (p14) HBMECs were analyzed for respiratory parameters using Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test. Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) were measured before and after treatment with oligomycin (1 µmol/L), FCCP (1.1 µmol/L) followed by antimycin/rotenone (0.5 µmol/L each), and data were analyzed by Wave 2.6 software. For mitofuel assay, (A). OCR. (B). Basal respiration. (C). ATP production (D). Maximal respiration. (E). Spare respiratory capacity (F). Proton leak. (G). Non-mitochondrial respiration. Data were represented as mean ± S.E.M and analyzed by student’s t-test. Data were pooled from three independent experiments. N = 12–15 wells/phenotype for the Cell Mito Stress Test. It is noted that various parameters in the bar graphs were derived from the same raw OCR data, thus, the relative distribution of data points may show some similarity

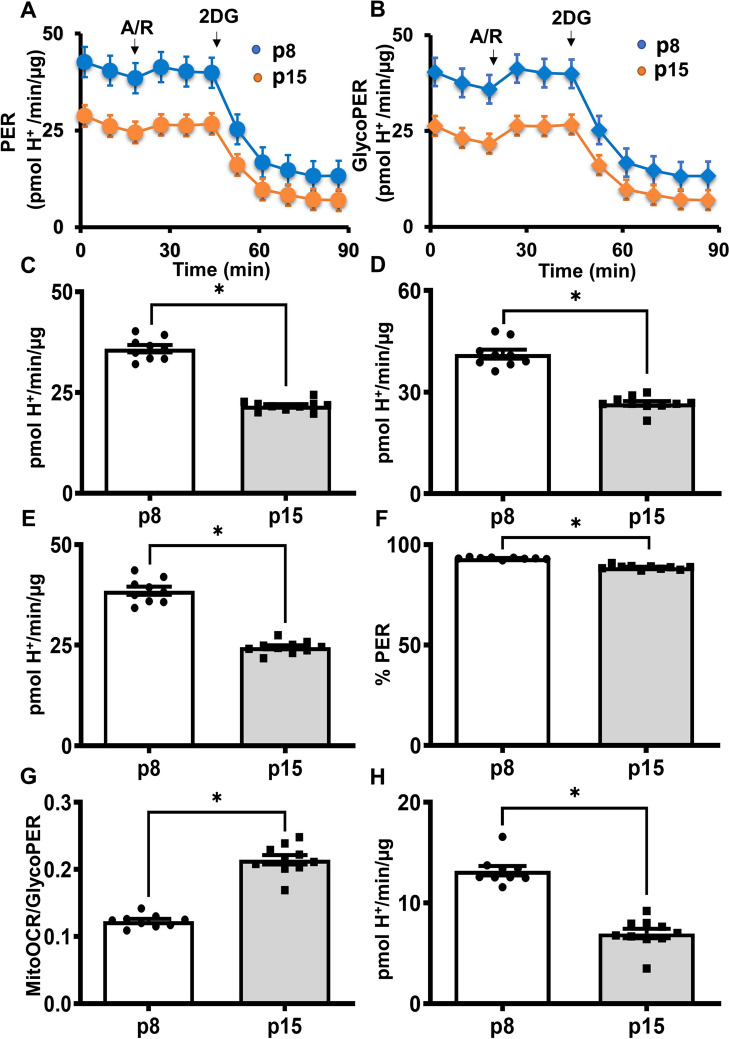

Pre-senescent HBMECs have impaired glycolysis.

Glycolytic parameters such as PER and the glycoPER were determined from the measurements of ECAR (Fig. 3A and B). Basal glycolysis was significantly reduced in pre-senescent cells (Fig. 3C). Similarly, the compensatory glycolysis, a surrogate indicator of the maximal glycolytic capacity of a cell, was significantly decreased in the pre-senescent cells (Fig. 3D). Basal PER is a measure of proton secretion from the cells that are derived from glycolysis and other minor proton secreting pathways. Basal PER was significantly decreased in the pre-senescent cells (Fig. 3E). Percent PER (% PER) from glycolysis was modestly but significantly decreased in the pre-senescent cells (Fig. 3F), whereas the MitoOCR/GlycoPER ratio, an indicator of the relative contributions of OXPHOS and glycolysis toward the cellular energy, was significantly increased in the pre-senescent cells (Fig. 3G). Interestingly, post-2DG acidification, an indicator of proton secretion from the non-glycolytic sources was significantly decreased in the pre-senescent cells (Fig. 3H). These observations were highly reproducible and the data from the replicate experiments were provided in supplemental figures (Supplemental Figure S4-S6).

Fig. 3.

Glycolysis was impaired in the pre-senescent HBMECs. Young (p8) and pre-senescent (p15) HBMECs were analyzed for glycolytic parameters using Seahorse XF Glycolytic Rate Assay. Oxygen consumption rates (OCR) and extracellular acidification rates (ECAR) were measured before and after treatment with antimycin/rotenone (A/R, 0.5 µmol/L each) followed by 2 deoxy-glucose (2DG, 50 mmol/L), and the data were analyzed by wave 2.6 software. (A). PER graph. (B). GlycoPER graph. (C). Basal glycolysis. (D). Compensatory glycolysis. (E). Basal proton efflux rate (PER). (F). Percentage PER from the glycolysis. (G). MitoOCR/Glyco PER. (H). Post-2-DG acidification. Data were represented as mean ± S.E.M and were analyzed by student’s t-test. ‘*’ indicate p ≤ 0.05. N = 9–10 wells per group. Please note that various parameters in the bar graphs were derived from the same raw ECAR data, thus, the relative distribution of data points may show some similarity. Experiments were repeated three times for reproducibility (data presented in the online supplementary materials)

Pre-senescent HBMECs exhibit diminished mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity.

We measured the OCR of HBMECs to determine mitochondrial respiratory function (Fig. 4A). Basal mitochondrial respiration and OCR related to ATP production were not different between the young and pre-senescent cells (Fig. 4B and C). However, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and proton leak were significantly reduced in the pre-senescent cells (Fig. 4D, E and F). In contrast, non-mitochondrial respiration was not altered between the young and pre-senescent cells (Fig. 4G). The data from the pooled experiments were provided in the supplemental figures (Supplemental Figure S7-S9).

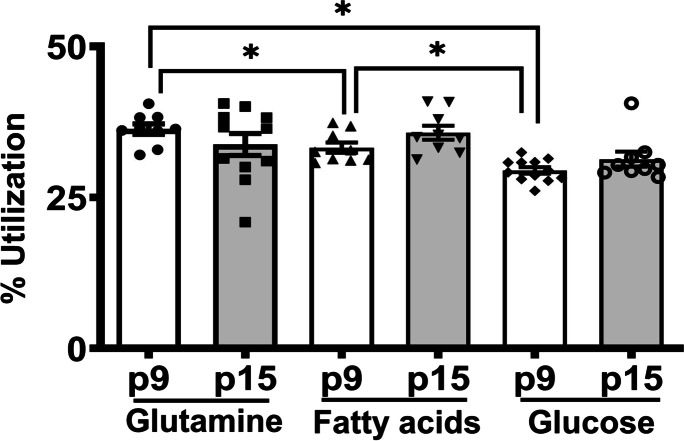

Mitochondrial OXPHOS utilizes all three substrates to a similar extent in HBMECs from young and pre-senescent cells.

Investigation of the energy substrate preferences showed that although OXPHOS in the young cells utilizes all the three fuels to a similar extent, a modest but statistically significant difference in preference for glutamate (36.3 ± 0.9%) and fatty acids (33.2 ± 0.9%) was detected compared to glucose (29.5 ± 0.5%), (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5). Interestingly, the OXPHOS in the pre-senescent cells utilized all fuels equally. Moreover, there was no significant difference among the HMBECs from the young and pre-senescent cells when the utilization of each substrate was compared (Fig. 5). The data from the pooled experiments were provided in the supplemental figures (Supplemental Figure S10).

Fig. 5.

Mitochondrial fuel preferences were not altered in the pre-senescent HBMECs. Young (p7) and pre-senescent (p15) HBMECs were analyzed for mitochondrial fuel preferences using Seahorse XF Mito Fuel Flex Test. OCR was measured before after treating with selective inhibitors of mitochondrial pyruvate (UK5099), fatty acid transporters (etomoxir) along the glutaminase inhibitor (BPTES). Data were represented as mean ± S.E.M and analyzed by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test and the differences between the young and pre-senescent cells for the same fuel were analyzed by the student’s t-test. ‘*’ indicate p ≤ 0.05. N = 9–12 wells for the Mito Fuel Flex Test

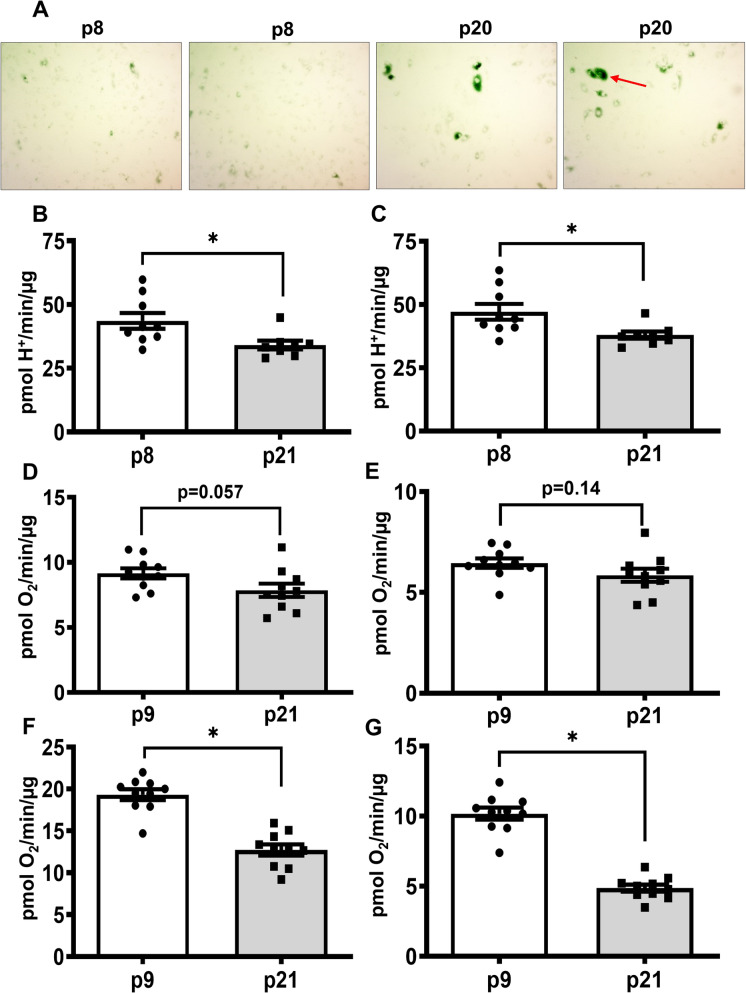

HBMECs at P20/P21 exhibit senescence and similar defects in OXPHOS and Glycolysis like pre-senescent cells

We observed initial signs of senescence at passage number 20, as β-galactosidase positive cells were significantly increased in these cultures (Fig. 6A). We screened p20/21 cells for glycolytic rate and mitostress assays to check whether these cells exhibit similar or worsened glycolytic and OXPHOS defects like pre-senescent cells. p20/p21 HBMECs exhibit a significant decrease in glycolytic parameters along with the mitochondrial maximal respiration and spare respiratory capacity, as observed in the case of pre-senescent cells (Fig. 6B-G). Interestingly, p20 HBMECs also show a strong trend toward a decrease in basal mitochondrial respiration and ATP production (p = 0.05 & 0.14 respectively, Fig. 6D and E), indicating worsening of the mitochondrial respiratory function with the aging. The replicate experiment data were given in supplemental figures (Supplemental Figure S11-S14). (Figure 7)

Fig. 6.

HBMECs at p20 exhibit significant senescent cells and continue presenting defects in glycolysis and OXPHOS: HBECs were stained for β- Galactosidase activity, a senescent marker using Senescence β-Galactosidase Staining Kit. The red arrow indicates the senescent cells. (A) HBMECs from p8/p9 and p20/p21 were analyzed for glycolytic and mitostress parameters using Seahorse XF Glycolytic Rate and Mitostress assays, respectively. (B) Basal Glycolysis. (C) Compensatory Glycolysis. (D) Basal Respiration. (E) ATP Production. (F) Maximal Respiration. (G) Spare Capacity. Data were represented as mean ± S.E.M and were analyzed by student’s t-test. ‘*’ indicate p ≤ 0.05. N = 9–10 wells per group. Please note that various parameters in the bar graphs were derived from the same raw ECAR data, thus, the relative distribution of data points may show some similarity. Additional glycolytic and mitostress parameters were given in the online supplementary materials along with the duplicate experiment

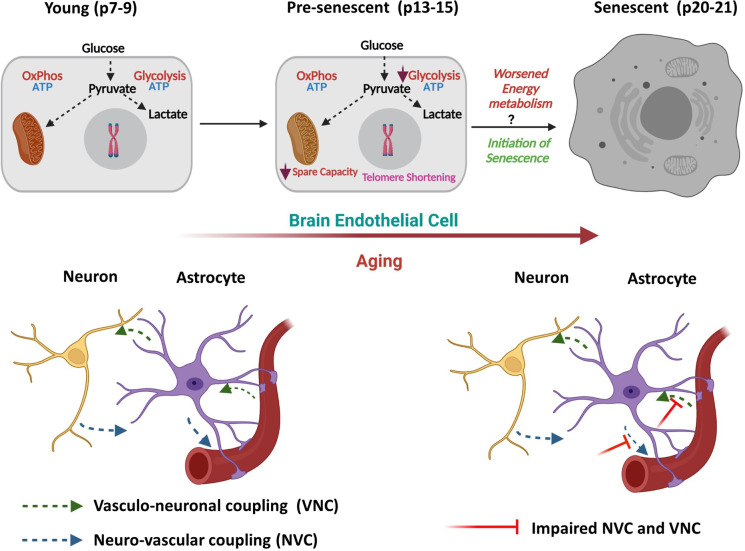

Fig. 7.

Schematic representation of the changes in bioenergetics pathways in HBMECs during aging (BioRender Software). Glycolysis is impaired along with the mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity in pre-senescent HBMECs (p14/p15) even before the initiation of senescence (p20/P21). Further worsening of glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration may trigger the cellular senescence at later stages of aging altering neurovascular coupling (NVC) and vasculo-neuronal coupling (VNC). Progression of bioenergetic defects in pre-senescence is associated with decreased telomerase activity and length

Discussion

In the present study, we characterized the bioenergetic differences between the young and pre-senescent primary HBMECs to understand the early metabolic changes associated with cellular senescence or aging. Given the established use of cell passaging as a model of in-vitro aging [13], the results from the present study also offer cell passaging as a method to examine pre-senescent changes in bioenergetics. We observed that pre-senescent cells displayed decreased telomere length and undetectable telomerase activity without signs of senescence markers, thus representing the pre-senescence. Notably, pre-senescent HBMECs exhibited reduced diminished cellular ATP production rate that was predominantly due to reduced glycolytic rate. Furthermore, pre-senescent cells displayed reduced basal and compensatory glycolysis as well as a decreased mitochondrial spare respiratory capacity. Senescent cells continued similar glycolytic defects with possible signs of worsened OXPHOS function. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of the alterations in the energy metabolism in the pre-senescent HBMECs.

Majority of the endothelial cell studies on glycolytic and mitochondrial pathways of bioenergetics utilized human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) [11, 13, 15, 16]. Evidence shows that glycolysis provides 85% of the cellular energy in endothelial cells [11] and is critical for proliferation, migration, and the angiogenesis process [17]. In most cell types, senescence is associated with increased glycolysis whereas, in senescent HUVECs, glycolysis was found to be unaltered or decreased [13, 16]. Considering the unique energy demands of BMECs, an efficient ATP production rate is critical to their physiology. In our study, we observed that at least 30–45% of the cellular ATP is generated from mitochondrial OXPHOS, which is even higher (~ 50%) in the pre-senescent cells. This is the first study to characterize OXPHOS contribution to the cellular ATP in BMECs and highlights the importance of mitochondria as a source of energy in these cells. This conflicts with observations in endothelial cells from other tissue beds that derive energy predominantly from the glycolysis [11]. Mitochondria were merely considered as signaling centers in the endothelial cells and contribute minimally to cellular ATP levels as they occupy only 2–6% of the cell volume [7, 8]. In contrast, mitochondria occupy 8–11% of the cell volume in BMECs but their contribution toward cellular energy was never previously examined [8]. Despite being in an oxygen-rich environment, endothelial cells rely mostly on glycolysis for their energy needs. This metabolic adjustment was proposed to provide oxygen availably to the deeper tissues. Interestingly, a recent study in humans has shown that although the brain weighs only 2% of body weight it receives 14.8% of cardiac output in men and 21.3% in women and decreases across the adult lifespan [18]. Moreover, the cardiac output distributed to the brain decreases across the adult lifespan and is inversely associated with body mass index [18]. Based on this, it may be argued that disproportionately high perfusion provides more than adequate oxygen for the needs of OXPHOS in neurons. Considering the obligatory dependence of neurons on glucose, equal reliance of BMECs on energy-efficient OXPHOS alongside glycolysis helps consume less glucose and make more glucose available for neuronal tissue. Furthermore, the energy pathway flexibility of the BMECs to modulate the glucose and oxygen flux is expected to support the local neuronal energy metabolism on demand. When young and pre-senescent cells are compared, we observed a significant decline in ATP production rates, which was mainly due to reduced contribution from glycolysis but not from OXPHOS. Paradoxically, pre-senescent cells rely more on the ATP generated from OXPHOS as indicated by their increased ATP rate index (MitoATP/GlycoATP).

A closer look at glycolysis through glycolytic rate assay showed that the pre-senescent cells have decreased basal and compensatory glycolysis, indicating a reduction in the contribution to cellular energy not only under basal conditions but also under conditions where mitochondrial/OXPHOS-dependent energy generation is abolished such as anoxia/ischemia. The glycolytic impairments in the aged brain endothelial cells may contribute to aging-associated microvascular dysfunction involving BBB, neurovascular coupling, and post-stroke angiogenesis for which glycolytic function is critical [12, 17, 19, 20]. Interestingly, pre-senescent cells derived fewer protons from the non-glycolytic pathways. Notably, previous studies reported induction of senescence in brain endothelial cells after treating with proton-pump inhibitors [21]. Thus, decreased proton secretion could also play a role in the aging of the HBMECs.

Mitochondria play a critical role in cellular signaling although they were not considered to be a significant contributor to cellular energetics [7]. Mitochondria are also critical for endothelial cell proliferation and migration, as tip cells undergo metabolic shift toward OXPHOS from the glycolysis during angiogenesis [10, 17, 22]. Notably, mitochondrial respiratory impairments have been shown to mediate post-stroke BBB dysfunction [9, 23, 24]. In the present study, we did not observe alterations in basal OCR in pre-senescent cells when compared to the young cells. However, consistent with our previous observations in aged mice brain microvessels [24], the maximal respiration and the spare respiratory capacity were diminished. These observations indicate the inability of the senescent HBMECs generates sufficient energy in the high-energy demanding conditions such as restoration of BBB breach or promotion of angiogenesis. Interestingly, impaired mitochondrial spare capacity has been found to underlie the progression of cellular senescence and aging in neurons [25, 26]. Considering the significance of mitochondrial respiration in BBB and angiogenesis, the defects in mitochondrial respiration in the aged brain endothelial cells could play a causative role in the aging-associated microvascular dysfunction. As aging is associated with reduced capillary density, neovascularization, and BBB breach which in turn play key roles in the pathophysiology of cognitive decline, stroke injury, and neurodegenerative diseases, impaired endothelial energetics could play a mechanistic role in these pathologies [27, 28]. Furthermore, as the aged BMECs rely more on mitochondrial OXPHOS due to impaired glycolysis, the elevated generation of mitochondrial superoxide could result in microvascular dysfunction, as its well-documented that mitochondrial ROS is involved in various age-related neurovascular pathologies [29, 30].

Cerebral autoregulation is critical for maintaining cerebral flow to neuronal tissue in basal conditions, whereas NVC is essential for directing the local blood flow to match the neuronal activity [31]. A recent study reported that the cerebral microvascular endothelial cells are the key cells in mediating NVC [32]. Along with NVC, vasculo-neuronal coupling (VNC) was proposed to play an important role in brain homeostasis. VNC involves changes in local CBF due to constriction and dilation of capillaries and arterioles influencing the regional neuronal activity [31]. It is well-established that aging results in diminished cerebral autoregulation and NVC but its effect on VNC is not established yet [31]. Considering the significance of bioenergetics in capillary endothelial function, the impaired OXPHOS and glycolysis in aged brain endothelial cells could disrupt cell–cell communications and alter the cerebral autoregulation, NVC, and VNC. Since impaired endothelial glycolysis and OXPHOS were previously shown to regulate BBB leak [9, 12], future studies will examine the physiological and pathological role of endothelial energetics in BBB, NVC, and VNC.

Along with glucose, mitochondria oxidize amino acids like glutamine and fatty acids through OXPHOS [33]. Though previous studies did not reveal the energy contribution of glutamine and fatty acids to the cellular ATP, their oxidation through OXPHOS was found to be indispensable for endothelial function and survival. Glutamine was found to contribute 30% of carbons in TCA cycle, with similar contributions from glucose and fatty acids [34]. Glutamine oxidation is essential for endothelial proliferation and angiogenesis [35]. In contrast, fatty acid oxidation in mitochondria significantly contributes to dNTP synthesis [34]. Similarly, mitochondrial utilization of fatty acids and glutamine has also been implicated in endothelial cell function and senescence [16, 36, 37]. In our study, we observed that brain endothelial cells utilize all three types of fuels for mitochondrial OXPHOS. Though the young cells slightly favor glutamine oxidation ahead of fatty acids and glucose, all three substrates approximately contributed equally to mitochondrial respiration. Considering the significant contribution of mitochondrial OXPHOS to the cellular ATP levels in BMECs, glutamine, and fatty acid oxidation also contribute significantly to the endothelial cell energy metabolism and the carbon mass.

Evidence supports the impact of aging on telomere length, telomere uncapping, and telomerase activity [38]. We observed reduced telomere length and undetectable telomerase activity in the pre-senescent cells suggesting early signs of aging. However, as shown in the supplemental data, markers of senescence including increased β-galactosidase activity, P21 immunofluorescence, and the increased senescence-related gene expression were not observed in the pre-senescent HBECs. The impairments of bioenergetics despite the absence of biochemical markers of senescence indicate that the impaired energy metabolism precedes and/or instigates the development of senescence consistent with the evidence from the literature [13, 16, 39]. The presence of significant alterations of energy pathways after 6–8 passages indicates that the aging of HBMECs is relatively more sensitive to impairments of bioenergetics relative to other endothelial cell types such as HUVECs [13]. Though we studied the telomerase activity and the telomere length to differentiate between the young and the pre-senescent cells, the possible role of decreased telomerase activity and telomere length in the observed defects in the glycolysis and OXPHOS cannot be ruled out. Previous studies reported counter-regulation between telomerase activity and the energy metabolism. Glucose restriction was shown to reduce telomerase activity whereas the hexokinase II, a rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis is regulated by telomerase [40] [41]. Further, telomerase was located in mitochondria along with the nucleus and shown to regulate mitochondrial biogenesis, respiration, and superoxide production[42]. Studies also reported the regulation of telomere shortening by mitochondrial uncoupling and hence the replicative senescence [43]. Further studies needed to confirm whether similar relation exists between telomerase and energy pathways in the HBMECs.

Limitations

We employed cultured cells to study the impact of aging by comparing HBMECs at low- and high-passage numbers in a manner consistent with a similar previous study [13] but providing a more comprehensive characterization of energetics. Although cultured HBMECs are the most widely used, we recognize that they are not the perfect substitute for native BMECs. However, based on our present data replicating the aging-related alterations reported in endothelial cell energetics [13], the bioenergetics we measured in HBMECs reasonably reflect the energetics of native BMECs. Further, the current observations are from the HBMECs derived from the male donor. As endothelial cell function and metabolism are significantly differed between the male and the female genders, it will be interesting to carryout similar experiments in female HMBECs [44]. These experiments will through a light on whether the aged female cells exhibit similar decline in energy metabolism like the male HBECs or else resistant to these changes. Another limitation of the study is that the lack of establishment of minimal passage number at which the HBMECs exhibit metabolic defects. Though it is ideal to determine the earlier passage number that exhibit defects in glycolysis and OXPHOS, we feel that it is technical challenging to establish the differences between the HMBECs that were only differed by one or two passages considering the sensitivity of the available techniques.

Concerning mitofuel analysis, etomoxir is a carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 (CPT1) inhibitor, UK5099 is mitochondrial pyruvate transporter (MPT) whereas the BPTES is the selective glutaminase 1 (GLS1) inhibitor. Though etomoxir was a selective CPT1 inhibitor, it has been shown previously that at high concentrations (200 µM) inhibits electron transport chain complex 1 and reduce incorporation of palmitic acid into mitochondrial cardiolipin (at 10 µM for two-hour incubation) [45, 46]. In the present study, very low levels of etomoxir (4 µM) were used for a short duration (5 min), thus, the contribution of off-target effects to the observed FA-dependent OCR is negligible in our experiments. UK5099 is a potent inhibitor of MPT along with monocarboxylate transporters (MCT) [47]. Brain endothelial cells express MCT1 that facilitates the diffusion of lactate and ketone bodies across the cell membrane [48]. It is unclear whether the UK5099 inhibits MCT1 at the used concentration (2 µM). However, a previous study reported that at high concentrations of UK5099 (10 µM), it promoted lactate secretion indicating that the selectivity to inhibit MPT is limited to low concentrations [47]. Further, UK5099 is 300-fold more selective toward MPT compared to MCTs [49]. BPTES is an allosteric inhibitor of GLS1 and shows no effect on other glutamine- or glutamate-metabolizing enzymes such as glutaminase 2, glutamate dehydrogenase, and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase even at high concentrations (10 µM) than the concentrations used in this study (3 µM) [50]. Furthermore, the percentages observed for substrate utilization in our experiments are identical to the percentages of carbon incorporation into the citrate from the previously reported studies, validating the current assay in the brain endothelial cells [34].

In conclusion, the pre-senescent HBMECs have impaired cellular ATP production rates mainly due to diminished glycolysis. In addition, these cells exhibit reduced compensatory glycolytic and spare mitochondrial respiratory capacities. Notably, impairments of energy pathways in pre-senescent cells were found accompanying decreased telomere length and reduced telomerase activity before the appearance of senescent changes. Thus, investigating the impact of energy metabolism on cellular senescence is critical to understanding the microvascular endothelial cell contribution to aging-associated brain disorders and helping to identify novel therapeutic targets.

Supplementary information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ms. Sufen Zheng for her technical help with the studies.

Funding

This research project was supported by the National Institutes of Health: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS094834 and NS114286—P.V. Katakam; NS114286 – R. Mostany; NS099539 – X. Wang), National Institute on Aging (AG047296 – R. Mostany; AG-063345 – D. Busija; AG074489 – P.V. Katakam and R. Mostany), National Heart, Lung, Blood Institute (HL093554 – D. Busija; HL133619 – S. Lindsey), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NS094834—P.V. Katakam). In addition, the study was supported by American Heart Association (National Center Scientist Development Grant, 14SDG20490359—P.V. Katakam; Greater Southeast Affiliate Predoctoral Fellowship Award, 16PRE27790122—V.N. Sure; Predoctoral Fellowship Award, 20PRE35211153—W.R. Evans. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Erdő F, Denes L and de Lange E. Age-associated physiological and pathological changes at the blood-brain barrier: A review. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2017; 37: 4–24. 2016/11/12. 10.1177/0271678x16679420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Toth P, Tarantini S, Csiszar A and Ungvari Z. Functional vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: mechanisms and consequences of cerebral autoregulatory dysfunction, endothelial impairment, and neurovascular uncoupling in aging. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology 2017; 312: H1-h20. 2016/10/30. 10.1152/ajpheart.00581.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Alonso A, Bittencourt MS, Callaway CW, Carson AP, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Das SR, Delling FN, Djousse L, Elkind MSV, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Jordan LC, Khan SS, Kissela BM, Knutson KL, Kwan TW, Lackland DT, Lewis TT, Lichtman JH, Longenecker CT, Loop MS, Lutsey PL, Martin SS, Matsushita K, Moran AE, Mussolino ME, O'Flaherty M, Pandey A, Perak AM, Rosamond WD, Roth GA, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Schroeder EB, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Stokes A, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Turakhia MP, VanWagner LB, Wilkins JT, Wong SS, Virani SS, American Heart Association Council on E, Prevention Statistics C and Stroke Statistics S. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2019 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2019; 139: e56-e528. 2019/02/01. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000659. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Eelen G, de Zeeuw P, Simons M and Carmeliet P. Endothelial cell metabolism in normal and diseased vasculature. Circulation research 2015; 116: 1231–1244. 2015/03/31. 10.1161/circresaha.116.302855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Eelen G, Cruys B, Welti J, De Bock K and Carmeliet P. Control of vessel sprouting by genetic and metabolic determinants. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2013; 24: 589–596. 2013/10/01. 10.1016/j.tem.2013.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Eelen G, de Zeeuw P, Treps L, Harjes U, Wong BW and Carmeliet P. Endothelial Cell Metabolism. Physiol Rev 2018; 98: 3–58. 2017/11/24. 10.1152/physrev.00001.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Caja S and Enríquez JA. Mitochondria in endothelial cells: Sensors and integrators of environmental cues. Redox biology 2017; 12: 821–827. 2017/04/28. 10.1016/j.redox.2017.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Oldendorf WH, Cornford ME and Brown WJ. The large apparent work capability of the blood-brain barrier: a study of the mitochondrial content of capillary endothelial cells in brain and other tissues of the rat. Ann Neurol 1977; 1: 409–417. 1977/05/01. 10.1002/ana.410010502. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Doll DN, Hu H, Sun J, Lewis SE, Simpkins JW and Ren X. Mitochondrial crisis in cerebrovascular endothelial cells opens the blood-brain barrier. Stroke 2015; 46: 1681–1689. 2015/04/30. 10.1161/strokeaha.115.009099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Diebold LP, Gil HJ, Gao P, Martinez CA, Weinberg SE and Chandel NS. Mitochondrial complex III is necessary for endothelial cell proliferation during angiogenesis. Nature metabolism 2019; 1: 158–171. 2019/05/21. 10.1038/s42255-018-0011-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.De Bock K, Georgiadou M, Schoors S, Kuchnio A, Wong BW, Cantelmo AR, Quaegebeur A, Ghesquiere B, Cauwenberghs S, Eelen G, Phng LK, Betz I, Tembuyser B, Brepoels K, Welti J, Geudens I, Segura I, Cruys B, Bifari F, Decimo I, Blanco R, Wyns S, Vangindertael J, Rocha S, Collins RT, Munck S, Daelemans D, Imamura H, Devlieger R, Rider M, Van Veldhoven PP, Schuit F, Bartrons R, Hofkens J, Fraisl P, Telang S, Deberardinis RJ, Schoonjans L, Vinckier S, Chesney J, Gerhardt H, Dewerchin M and Carmeliet P. Role of PFKFB3-driven glycolysis in vessel sprouting. Cell 2013; 154: 651–663. 2013/08/06. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Salmina AB, Kuvacheva NV, Morgun AV, Komleva YK, Pozhilenkova EA, Lopatina OL, Gorina YV, Taranushenko TE and Petrova LL. Glycolysis-mediated control of blood-brain barrier development and function. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology 2015; 64: 174–184. 2015/04/23. 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Kuosmanen SM, Sihvola V, Kansanen E, Kaikkonen MU and Levonen AL. MicroRNAs mediate the senescence-associated decline of NRF2 in endothelial cells. Redox biology 2018; 18: 77–83. 2018/07/10. 10.1016/j.redox.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Sure VN, Sakamuri S, Sperling JA, Evans WR, Merdzo I, Mostany R, Murfee WL, Busija DW and Katakam PVG. A novel high-throughput assay for respiration in isolated brain microvessels reveals impaired mitochondrial function in the aged mice. Geroscience 2018; 40: 365–375. 2018/08/04. 10.1007/s11357-018-0037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Xu Y, An X, Guo X, Habtetsion TG, Wang Y, Xu X, Kandala S, Li Q, Li H, Zhang C, Caldwell RB, Fulton DJ, Su Y, Hoda MN, Zhou G, Wu C and Huo Y. Endothelial PFKFB3 plays a critical role in angiogenesis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2014; 34: 1231–1239. 2014/04/05. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.303041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Unterluggauer H, Mazurek S, Lener B, Hutter E, Eigenbrodt E, Zwerschke W and Jansen-Durr P. Premature senescence of human endothelial cells induced by inhibition of glutaminase. Biogerontology 2008; 9: 247–259. 2008/03/05. 10.1007/s10522-008-9134-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Yetkin-Arik B, Vogels IMC, Neyazi N, van Duinen V, Houtkooper RH, van Noorden CJF, Klaassen I and Schlingemann RO. Endothelial tip cells in vitro are less glycolytic and have a more flexible response to metabolic stress than non-tip cells. Scientific reports 2019; 9: 10414. 2019/07/20. 10.1038/s41598-019-46503-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Xing CY, Tarumi T, Liu J, Zhang Y, Turner M, Riley J, Tinajero CD, Yuan LJ and Zhang R. Distribution of cardiac output to the brain across the adult lifespan. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2017; 37: 2848–2856. 2016/11/01. 10.1177/0271678X16676826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.He X, Zeng H, Chen ST, Roman RJ, Aschner JL, Didion S and Chen JX. Endothelial specific SIRT3 deletion impairs glycolysis and angiogenesis and causes diastolic dysfunction. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2017; 112: 104–113. 2017/09/25. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Graves SI and Baker DJ. Implicating endothelial cell senescence to dysfunction in the ageing and diseased brain. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2020; 127: 102–110. 2020/03/13. 10.1111/bcpt.13403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Yepuri G, Sukhovershin R, Nazari-Shafti TZ, Petrascheck M, Ghebre YT and Cooke JP. Proton Pump Inhibitors Accelerate Endothelial Senescence. Circulation research 2016; 118: e36–42. 2016/05/12. 10.1161/circresaha.116.308807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Yetkin-Arik B, Vogels IMC, Nowak-Sliwinska P, Weiss A, Houtkooper RH, Van Noorden CJF, Klaassen I and Schlingemann RO. The role of glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration in the formation and functioning of endothelial tip cells during angiogenesis. Scientific reports 2019; 9: 12608. 2019/09/01. 10.1038/s41598-019-48676-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Otolorin EO, Falase EA and Ladipo OA. A comparative study of three oral contraceptives in Ibadan: Norinyl 1/35, Lo-Ovral and Noriday 1/50. African journal of medicine and medical sciences 1990; 19: 15–22. 1990/03/01. [PubMed]

- 24.Lee MJ, Jang Y, Han J, Kim SJ, Ju X, Lee YL, Cui J, Zhu J, Ryu MJ, Choi SY, Chung W, Heo C, Yi HS, Kim HJ, Huh YH, Chung SK, Shong M, Kweon GR and Heo JY. Endothelial-specific Crif1 deletion induces BBB maturation and disruption via the alteration of actin dynamics by impaired mitochondrial respiration. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 2020; 40: 1546–1561. 2020/01/29. 10.1177/0271678x19900030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Desler C, Hansen TL, Frederiksen JB, Marcker ML, Singh KK and Juel Rasmussen L. Is There a Link between Mitochondrial Reserve Respiratory Capacity and Aging? Journal of aging research 2012; 2012: 192503. 2012/06/22. 10.1155/2012/192503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Bell SM, De Marco M, Barnes K, Shaw PJ, Ferraiuolo L, Blackburn DJ, Mortiboys H and Venneri A. Deficits in Mitochondrial Spare Respiratory Capacity Contribute to the Neuropsychological Changes of Alzheimer's Disease. Journal of personalized medicine 2020; 10 2020/05/06. 10.3390/jpm10020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Brown WR and Thore CR. Review: cerebral microvascular pathology in ageing and neurodegeneration. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology 2011; 37: 56–74. 2010/10/16. 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Goodall EF, Wang C, Simpson JE, Baker DJ, Drew DR, Heath PR, Saffrey MJ, Romero IA, Wharton SB. Age-associated changes in the blood-brain barrier: comparative studies in human and mouse. Neuropathology Applied Neurobiology. 2018;44:328–340. doi: 10.1111/nan.12408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stefanatos R, Sanz A. The role of mitochondrial ROS in the aging brain. FEBS Letters. 2018;592:743–758. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkins HM, Swerdlow RH. Mitochondrial links between brain aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Translational Neurodegeneration. 2021;10:33. doi: 10.1186/s40035-021-00261-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Presa JL, Saravia F, Bagi Z and Filosa JA. Vasculo-Neuronal Coupling and Neurovascular Coupling at the Neurovascular Unit: Impact of Hypertension. Frontiers in Physiology 2020; 11. Review. 10.3389/fphys.2020.584135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Longden TA, Dabertrand F, Koide M, Gonzales AL, Tykocki NR, Brayden JE, Hill-Eubanks D, Nelson MT. Capillary K+-sensing initiates retrograde hyperpolarization to increase local cerebral blood flow. Nature Neuroscience. 2017;20:717–726. doi: 10.1038/nn.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eelen G. Zeeuw Pd, Treps L, Harjes U, Wong BW and Carmeliet P. Endothelial Cell Metabolism Physiological Reviews. 2018;98:3–58. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00001.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoors S, Bruning U, Missiaen R, Queiroz KC, Borgers G, Elia I, Zecchin A, Cantelmo AR, Christen S, Goveia J, Heggermont W, Goddé L, Vinckier S, Van Veldhoven PP, Eelen G, Schoonjans L, Gerhardt H, Dewerchin M, Baes M, De Bock K, Ghesquière B, Lunt SY, Fendt SM and Carmeliet P. Fatty acid carbon is essential for dNTP synthesis in endothelial cells. Nature 2015; 520: 192–197. 2015/04/02. 10.1038/nature14362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Huang H, Vandekeere S, Kalucka J, Bierhansl L, Zecchin A, Brüning U, Visnagri A, Yuldasheva N, Goveia J, Cruys B, Brepoels K, Wyns S, Rayport S, Ghesquière B, Vinckier S, Schoonjans L, Cubbon R, Dewerchin M, Eelen G and Carmeliet P. Role of glutamine and interlinked asparagine metabolism in vessel formation. Embo j 2017; 36: 2334–2352. 2017/07/01. 10.15252/embj.201695518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Quijano C, Cao L, Fergusson MM, Romero H, Liu J, Gutkind S, Rovira, II, Mohney RP, Karoly ED and Finkel T. Oncogene-induced senescence results in marked metabolic and bioenergetic alterations. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 2012; 11: 1383–1392. 2012/03/17. 10.4161/cc.19800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Fafián-Labora J, Carpintero-Fernández P, Jordan SJD, Shikh-Bahaei T, Abdullah SM, Mahenthiran M, Rodríguez-Navarro JA, Niklison-Chirou MV and O'Loghlen A. FASN activity is important for the initial stages of the induction of senescence. Cell death & disease 2019; 10: 318. 2019/04/10. 10.1038/s41419-019-1550-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Liu Y, Bloom SI and Donato AJ. The role of senescence, telomere dysfunction and shelterin in vascular aging. Microcirculation 2019; 26: e12487. 2018/06/21. 10.1111/micc.12487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Tarantini S, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Fulop G, Kiss T, Balasubramanian P, DelFavero J, Ahire C, Ungvari A, Nyul-Toth A, Farkas E, Benyo Z, Toth A, Csiszar A and Ungvari Z. Treatment with the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor PJ-34 improves cerebromicrovascular endothelial function, neurovascular coupling responses and cognitive performance in aged mice, supporting the NAD+ depletion hypothesis of neurovascular aging. Geroscience 2019; 41: 533–542. 2019/11/05. 10.1007/s11357-019-00101-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Wardi L, Alaaeddine N, Raad I, Sarkis R, Serhal R, Khalil C, Hilal G. Glucose restriction decreases telomerase activity and enhances its inhibitor response on breast cancer cells: possible extra-telomerase role of BIBR 1532. Cancer Cell International. 2014;14(60):20140704. doi: 10.1186/1475-2867-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roh J-i, Kim Y, Oh J, Kim Y, Lee J, Lee J, Chun K-H and Lee H-W. Hexokinase 2 is a molecular bridge linking telomerase and autophagy. PLOS ONE 2018; 13: e0193182. 10.1371/journal.pone.0193182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Zheng Q, Huang J and Wang G. Mitochondria, Telomeres and Telomerase Subunits. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2019; 7. Review. 10.3389/fcell.2019.00274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Passos JF, Saretzki G, Ahmed S, Nelson G, Richter T, Peters H, Wappler I, Birket MJ, Harold G, Schaeuble K, Birch-Machin MA, Kirkwood TBL, von Zglinicki T. Mitochondrial Dysfunction Accounts for the Stochastic Heterogeneity in Telomere-Dependent Senescence. PLoS Biology. 2007;5:e110. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanhewicz AE, Wenner MM and Stachenfeld NS. Sex differences in endothelial function important to vascular health and overall cardiovascular disease risk across the lifespan. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology 2018; 315: H1569-h1588. 20180914. 10.1152/ajpheart.00396.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Yao CH, Liu GY, Wang R, Moon SH, Gross RW and Patti GJ. Identifying off-target effects of etomoxir reveals that carnitine palmitoyltransferase I is essential for cancer cell proliferation independent of β-oxidation. PLoS biology 2018; 16: e2003782. 2018/03/30. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2003782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Xu FY, Taylor WA, Hurd JA, Hatch GM. Etomoxir mediates differential metabolic channeling of fatty acid and glycerol precursors into cardiolipin in H9c2 cells. Journal of Lipid Research. 2003;44:415–423. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200335-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong Y, Li X, Yu D, Li X, Li Y, Long Y, Yuan Y, Ji Z, Zhang M, Wen JG, Nesland JM and Suo Z. Application of mitochondrial pyruvate carrier blocker UK5099 creates metabolic reprogram and greater stem-like properties in LnCap prostate cancer cells in vitro. Oncotarget 2015; 6: 37758–37769. 2015/09/29. 10.18632/oncotarget.5386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Wang J, Cui Y, Yu Z, Wang W, Cheng X, Ji W, Guo S, Zhou Q, Wu N, Chen Y, Chen Y, Song X, Jiang H, Wang Y, Lan Y, Zhou B, Mao L, Li J, Yang H, Guo W, Yang X. Brain Endothelial Cells Maintain Lactate Homeostasis and Control Adult Hippocampal Neurogenesis. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;25:754–767.e759. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gray LR, Tompkins SC and Taylor EB. Regulation of pyruvate metabolism and human disease. Cell Mol Life Sci 2014; 71: 2577–2604. 12/21. 10.1007/s00018-013-1539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Robinson MM, McBryant SJ, Tsukamoto T, Rojas C, Ferraris DV, Hamilton SK, Hansen JC and Curthoys NP. Novel mechanism of inhibition of rat kidney-type glutaminase by bis-2-(5-phenylacetamido-1,2,4-thiadiazol-2-yl)ethyl sulfide (BPTES). The Biochemical journal 2007; 406: 407–414. 2007/06/22. 10.1042/bj20070039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.