Abstract

0-1 Knapsack problem (KP) is NP-hard. Approximate solution is vital for solving KP exactly. In this paper, a fast polynomial time approximate solution (FPTAS) is proposed for KP. FPTAS is a local search algorithm. The best approximate solution to KP can be found in the neighborhood of the solution of upper bound for exact k-item knapsack problem (E-kKP) where k is near to the critical item s. FPTAS, in practice, often achieves high accuracy with high speed in solving KP. The computational experiments show that the approximate algorithm for KP is valid.

1. Introduction

0-1 Knapsack problem (KP) is a classical combinatorial optimization problem. KP is NP-hard. Knapsack problems were used to model capital budgeting problems in which investment projects are to be selected subject to expenditure limitations. Additionally, the knapsack problem has been used to model loading problems. Knapsack problems, moreover, arise as suboptimization problems in solving larger optimization problem [1]. KP can be formulated as follows:

| (1) |

where pi is the profit of item i, wi is the weight of item i, c is the capacity of the knapsack, n is the number of items in KP, and variable xi = 0 or 1 indicates whether item i is selected or not. Without loss of generality, it is assumed that all items are arranged in nonincreasing order of efficiency.

| (2) |

It is very important to find a fast polynomial approximation for KP in practice. Greedy algorithm [1], an approximate algorithm for KP, is on the basis of certain rules, such as the item being selected with priority over larger efficiency, larger profit, or smaller weight. Greedy algorithm is O(n) time complexity, but it is not an ɛ-approximate algorithm [1]. Approximation algorithm is often k-neighborhood local search method. Increasing the radius k of the neighborhood can improve the accuracy of the approximate algorithm [1, 2]. While PTAS for KP typically require only O(n) storage, all FPTAS are based on dynamic programming and their memory requirement increases rapidly with the accuracy ɛ, which makes them impractical even for relatively big values of ɛ [3]. Heuristics rules are adopted to decrease the calculation in searching accurate approximation, such as harmony search algorithm [4, 5], amoeboid organism algorithm [6], cuckoo search algorithm [5, 7], binary monarch butterfly optimization [8], cognitive discrete gravitational search algorithm [9], bat algorithm [10], and wind driven optimization [11]. Nowadays, it is tend to combine different heuristics together in solving combinatorial optimization problem, such as mixed-variable differentiate evolution [12], self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm [13], two-stage cooperative evolutionary algorithm [14], cooperative water wave optimization algorithm with reinforcement learning [15], and cooperative multi-stage hyper-heuristic algorithm [16]. However, these algorithms cannot guarantee the accuracy of the solution of KP. Meanwhile, these methods for the solution to KP are generally time-consuming. More domain knowledge is necessary for better algorithm. Pisinger gave an exact algorithm for KP [17] which is based on an expanding core. The items not included in the core are certain to be selected or not in the optimal solution, while the items in the core are uncertain to be selected or not in the optimal solution. He found that algorithms solving some kinds of core problem may be stuck by difficult cores [18]. For example, KP is determined by

| (3) |

It is easy to find that the core of KP is [1, 10000], so this problem is difficult to tackle by the exact algorithm in [17]. In this paper, it is easy to get an approximate solution of KP which objective value is 6395122580. The solution can be proved to be the optimal solution.

In this paper, a fast polynomial approximate solution is proposed for 0-1 knapsack problems based on the solution of its upper bound. Firstly, an upper bound is presented based on the exact k-item knapsack problem E-kKP in Section 2. Secondly, an initial solution of KP is constructed on the basis of the solution of upper bound of E-kKP in Section 3.1. Thirdly, the approximate solution is proposed to find the best solution in the neighborhood of the initial solution in Section 3.2. In Section 3.3, the best approximation solution is achieved by comparison with number of items changing. In Section 3.4, the calculation for the approximate solution of KP is analyzed. In Section 4, computational experiments of KP are implemented. The results show that the approximate solution proposed in this paper can achieve high accuracy in general. It implicates that the exact solution to KP is similar to the solution to the upper bound. The algorithm proposed here is a fast polynomial approximate solution to KP.

2. Upper Bound for KP

If there are exact k objects selected in the knapsack, then KP is an exact k-item knapsack problem E-kKP formulated as follows [3]:

| (4) |

The upper bound of E-kKP may be achieved by Lagrangian relaxation of capacity constraint:

| (5) |

Suppose that

| (6) |

Then

| (7) |

So L(k, λ) can be solved by sorting pi − λwi in descending order in O (nlnn) time if λ and k are fixed. The upper bound of E-kKP is formulated as follows:

| (8) |

It can be proved that L(k, λ) is a unimodal function of λ if k is fixed. Bk can be quickly solved by linear search algorithm [19]. So Bk can be solved in O (nlnn) time.

The upper bound of KP is the maximum value of Bk:

| (9) |

It can be proved that Bk increases when k < s − 1 and decreases when k > s, where the critical item s satisfies.

| (10) |

So the upper bound of KP is

| (11) |

Example 1 . —

Consider the instance of KP listed in Table 1. The capacity is 467.8435.

Here the critical item s is 20. There is no feasible solution with 20 items included in the knapsack. So the upper bound B20= 0. If k is 19, we have the optimal ratio λ19 = 1.0003251 and the upper bound B19 = 486.9565 by (8). The solution of L(19, λ19) is u(19) = (ud19i)as follows:

(12) So the upper bound of KP is 486.9565.

We test different upper bounds of KP from Pisinger's paper [20], where the weights and profits of items are randomized. The instances listed in Table2 are tested to compare our proposed method with the existing upper bounds, such as the upper bound UMT2 proposed by Martello and Toth [21], the improved upper bound UMTM [22] and the upper bound Ukmax with maximum cardinality [23]. The difficult instances can be constructed as follows [20]:

Uncorrelated instances with similar weights: Weights wi are distributed in [R, R + 100] and the profits pi in [1, 1000].

Uncorrelated data instances: pi and wi are chosen randomly in [1, R].

Weakly correlated instances: Weights wi are chosen randomly in [1, R] and the profits pi in [wi − 0.1 R, wi + 0.1 R] such that pi ≥ 1.

Strongly correlated instances: Weights wi are distributed in [1, R] and pi = wi + 0.1R.

Inverse strongly correlated instances: Profits pi are distributed in [1, R] and wi = pi+0.1R.

Almost strongly correlated instances: Weights wi are distributed in [1, R] and the profits pi in [wi + 0.098R, wi + 0.102R].

Subset sum instances: Weights wj are randomly distributed in [1, R] and pi = wi.

Circle instances circle (d): The weights are uniformly distributed in [1, R] and for each weight w the corresponding profit is chosen as where d is 2/3.

Profit ceiling instances pceil (d): The weights of the n items are randomly distributed in [1, R], and the profits are set to pi = d⌈wi/d⌉. The parameter d was chosen as d = 3.

Multiple strongly correlated instances mstr (k1, k2, d): The weights of the n items are randomly distributed in [1, R]. If the weight wi is divisible by d, then we set the profit pi: = wi + k1; otherwise set it to pi: = wi + k2. We set d: = 6 here.

For each instance type, a series of K = 100 instances is performed, and the capacity is determined by (13). All the instances above are generated with data range R = 103, 104, 105, 106 or 107.

(13) There are 100 instances for each type of KP where the capability is described as follows:

(14) The mean relative error of upper bounds to the best upper bound of KP is listed in Table 3.

From Table 3, we find that the relative error of the upper bound B is the minimum in general. The upper bounds of 5000 instances are carried out with different methods. More details are listed in Table 4.

From Table 4, we find that Ukmax is the best upper bound in 2025 instances. The upper bound B plays an important role in obtaining the best upper bound even if s ≤ kmax.

The upper bound can gather most items selected in the optimal solution all together. For example, KP is determined by

(15) A maximum of 631 items can be selected in the knapsack. The upper bound Bs−1(s=632) and the solution u(s − 1) are as follows:

(16) The initial solution z(s − 1) is equal to u(s − 1). The best solution ya(s − 1) in the neighborhood ∪h=14N(z(s − 1), 2h) can be described as follows:

(17) It is obviously that there is little difference between z(s − 1) and ya(s − 1). Relation between (pi − 106310wi) and wi is displayed in Figure 1. Relation between pi/wi and wi is displayed in Figure 2. It is found that (pi − 106310wi) changes more dramatically than pi/wi. It makes solution to KP easy.

From Figure 1, we can see that (pi − 106310wi) of all items selected are larger, while the others are smaller. It is easy to get a better solution on the basis of (pi − 106310wi) than that on the basis of efficiency pi/wi.

Table 1.

Weight and profit of items.

| i | w i | p i |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.7856 | 2.7924 |

| 2 | 4.877 | 5.8853 |

| 3 | 6.3493 | 7.3521 |

| 4 | 7.0943 | 8.0992 |

| 5 | 7.8807 | 8.885 |

| 6 | 8.5593 | 9.5616 |

| 7 | 13.9249 | 14.9319 |

| 8 | 19.6114 | 20.6148 |

| 9 | 21.0881 | 22.0925 |

| 10 | 24.2688 | 25.2767 |

| 11 | 27.3441 | 28.3472 |

| 12 | 31.618 | 32.6189 |

| 13 | 32.7739 | 33.7797 |

| 14 | 32.787 | 33.7898 |

| 15 | 33.9368 | 34.9379 |

| 16 | 37.1566 | 38.1662 |

| 17 | 37.887 | 38.892 |

| 18 | 39.6104 | 40.6175 |

| 19 | 40.014 | 41.0159 |

| 20 | 40.7362 | 41.7432 |

| 21 | 42.4565 | 43.463 |

| 22 | 45.2896 | 46.2899 |

| 23 | 45.6688 | 46.6693 |

| 24 | 45.7868 | 46.7932 |

| 25 | 46.6997 | 47.7013 |

| 26 | 47.8583 | 48.866 |

| 27 | 47.8753 | 48.8848 |

| 28 | 47.9746 | 48.9822 |

| 29 | 48.2444 | 49.2448 |

| 30 | 48.5296 | 49.5335 |

Table 2.

Weights and profits of knapsack problems from Pisinger's paper [20].

| No. | (wi, pi) (i = 1, 2,…, 104) | No. | (wi, pi) (i = 1, 2,…, 104) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ([R+100ui], ⌈1000vi⌉) | 2 | (⌈Rui⌉, ⌈Rvi⌉) |

| 3 | ([Rui], [R(ui+0.2vi − 0.1)]) | 4 | ([Rui], [Rui+0.1R]) |

| 5 | ([Rvi+0.1R], [Rvi]) | 6 | ([Rui+0.098R], [R(ui+0.102R)]) |

| 7 | (⌈Rui⌉, ⌈Rui⌉) | 8 | |

| 9 | ([Rui], ⌈Rui/3⌉) | 10 |

∗ Note. ui and vi are uniformly distributed in [0,1]. R = 103, 104, 105, 106 or 107.

Table 3.

Mean relative error of upper bounds to the best upper bound of (KP) (ppm).

| (No, R) | U MT2 | U MTM | U kmax | B | (No, R) | U MT2 | U MTM | U kmax | B |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1, 103) | 4.6696 | 4.6696 | 4.6869 | 0 | (2, 103) | 0.0138 | 0.0031 | 0.0421 | 0.0174 |

| (1, 104) | 91.413 | 91.3869 | 81.4422 | 0 | (2, 104) | 0.0345 | 0.0075 | 0.0465 | 0.0189 |

| (1, 105) | 60.2607 | 60.2542 | 43.2765 | 0 | (2, 105) | 0.0194 | 0.005 | 0.0351 | 0.0164 |

| (1, 106) | 61.0366 | 61.0366 | 0 | 0 | (2, 106) | 0.0258 | 0.0057 | 0.0391 | 0.0152 |

| (1, 107) | 61.3372 | 61.3372 | 0 | 0 | (2, 107) | 0.0274 | 0.0069 | 0.0466 | 0.018 |

| (3, 103) | 0.0116 | 0.0049 | 0.0179 | 0 | (4, 103) | 28.7876 | 28.7876 | 0 | 0 |

| (3, 104) | 0.0031 | 0 | 0.0196 | 0.0044 | (4, 104) | 34.656 | 34.6518 | 0 | 0 |

| (3, 105) | 0.0148 | 0.0018 | 0.027 | 0.016 | (4, 105) | 31.5535 | 31.5456 | 0 | 0 |

| (3, 106) | 0.0114 | 0.0016 | 0.0166 | 0.0071 | (4, 106) | 27.5082 | 27.5001 | 0 | 0 |

| (3, 107) | 0.0066 | 0.0022 | 0.0105 | 0.0031 | (4, 107) | 25.7493 | 25.7467 | 0 | 0 |

| (5, 103) | 38.9054 | 38.9054 | 38.9054 | 0 | (6, 103) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (5, 104) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (6, 104) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (5, 105) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (6, 105) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (5, 106) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (6, 106) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (5, 107) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (6, 107) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (7, 103) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (8, 103) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (7, 104) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (8, 104) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (7, 105) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (8, 105) | 22.8602 | 22.8602 | 0 | 0 |

| (7, 106) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (8, 106) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (7, 107) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (8, 107) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (9, 103) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (10, 103) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (9, 104) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | (10, 104) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (9, 105) | 16.1344 | 16.1344 | 0 | 0 | (10, 105) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (9, 106) | 30.1447 | 30.1447 | 0 | 0 | (10, 106) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (9, 107) | 8.9156 | 8.9156 | 8.9156 | 0 | (10, 107) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

∗ The best upper bound is min{UMT2, UMTM, Ukmax, B} in this paper.

Table 4.

Sum of the best upper bounds in 5000 instances.

| Upper bound | Sum of the best upper bound | Percentage of the best upper bound (%) | Sum of the best upper bounds equal to B |

|---|---|---|---|

| U MT2 | 1520 | 30.40 | 1495 |

| U MTM | 1925 | 38.50 | 1548 |

| U kmax | 2025 | 40.50 | 2025 |

| B | 4623 | 92.46 | 4623 |

Figure 1.

Relation between (pi − 106310wi) and wi.

Figure 2.

Relation between (pi/wi) and wi.

3. Approximate Solutions

The approximate solution to E-kKP is a solution to KP. We obtain the best approximate solution to KP by comparison to approximate solutions for E-kKP where k is near to the critical item s. In order to achieve a better solution to E-kKP, we firstly obtain an initial solution on the basis of the solution to the upper bound of E-kKP. Then the initial solution is developed by local search in the neighborhood of the initial solution. At last, the approximate solution to KP is the best approximate solution to E-kKP with various k. The upper bound of E-kKP is used to decrease calculation. The solution to the upper bound of E-kKP and the upper bound make key contribution in FPTAS to KP.

3.1. Initial Solution to E-kKP

Let u(k) = (udki) be an optimal solution to the upper bound Bk. We may obtain an initial solution to E-kKP on the basis of u(k). The initial solution z(k) to E-kKP is determined by

| (18) |

In Example 1, z(19) is an initial solution and its objective value is

| (19) |

3.2. Approximate Solution to E-kKP

Approximate solution to E-kKP is the best solution in the neighborhood of z(k). Let N(z(k), 2h) be a neighborhood of z(k) that is defined by

| (20) |

It is obvious that the size of N(z(k), 2h) increases with h. But it is unnecessary to take into account all elements of N(z(k), 2h). Algorithm 1 is a fast algorithm for searching the best solution in N(z(k), 2h).

Algorithm 1.

Approximate solution to (E-kKP).

In order to decrease the calculation for the approximate solution to KP, N(z(k), 2h) is redefined by (21) and Step 1 in Algorithm 1 is modified correspondingly.

| (21) |

where

| (22) |

From (21), we know that the size of N(z(k), 2h)(h = 1,2,3,4) is limited. In order to search for the best solution, it is unnecessary to seek all solutions in N(z(k), 2h). Let

| (23) |

The best approximate solution corresponds to max {ps2 − ps1|ws2 ≤ ws1}, so the calculation is O (nlnn) time when h equals to 1. A better solution is generated if the profit sum of h items selected in the knapsack is less than that of h items not selected in the knapsack, and the capacity constraint still holds at the same time. On the other hand, the calculation decreases via variable reduction in practice.

In Example 1, let the approximate solution xa equal to z(19) and objective value fa equal to f(z(19)) firstly, and then the approximate solution xa is updated by the best solution ya(19) in N(z(19), 2) if possible.

| (24) |

Similarly, xa is replaced by the best solution ya(19) in N(z(19), 4) if possible.

| (25) |

There is no better solution of KP in N(z(19), 6) and N(z(19), 8). We get an approximate solution ya(19) with 19 items selected and the approximate objective value is 486.9426.

3.3. Approximation Algorithm of KP

Let xa describe the best approximate solution to KP in (26).

| (26) |

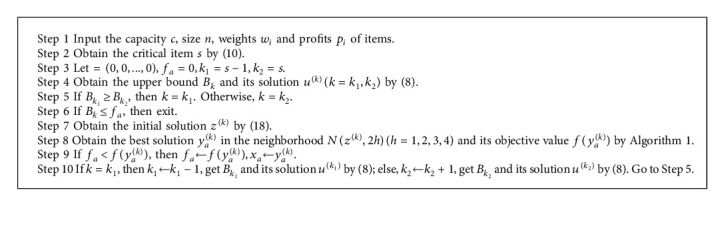

We can obtain the approximate solution xa of KP by Algorithm 2.

Algorithm 2.

Approximate Algorithm for (KP).

In Example 1, we obtain fa=486.9426 when k = 19.

| (27) |

The best approximate solution xa = (xd19i) for KP and its objective value are as follows:

| (28) |

It may be proved that xa is the optimal solution to KP in Example 1.

3.4. Calculation Analysis

Approximation algorithms for KP based on upper bound of E-kKP runs in polynomial time. Calculation for the upper bound of E-kKP is less than O (nlnn) for a given E-kKP. We obtain the approximate solution to KP on the basis of the upper bound of E-kKP where k is an integer close to s. For a given k, the initial solution is determined by (13). It takes O (nlnn) time to develop the initial solution in the neighborhood N(z(k), h) (h = 1, 2,…, 4) defined by (21). Hence, it takes at most O (nlnn) time to achieve the approximate solution to E-kKP. Generally, we obtain the best approximate solution for KP among the approximate solutions for E-kKP where k is near the critical item s. Hence, the calculation for approximate solution to KP is less than O (nlnn).

In Algorithm 1, we search for the best solution in N(z(k), h) defined by (21). In order to develop the approximate solution quickly, the weight sum of h items is sorted in ascending order firstly, and then the profit sum of h items selected in the knapsack is compared with the profit sum of h items not selected. So the storage needed in Algorithm 1 is O(n) when h is fixed at 1, 2, 3, or 4. In Algorithm 2, we have the best solution to KP by comparison to the best approximate solution to E-kKP where k is an integer close to s. So the storage of the approximate algorithm for KP is O(n).

3.5. Accuracy Analysis

All feasible solutions to KP are in the search scope of approximation algorithm with changing k and h. So approximation algorithm for KP is an ε-approximation algorithm. From one aspect, weights, profits, capacity and size of KP have influence on the accuracy of an approximation algorithm. From another aspect, the search scope of the approximation algorithm has influence on its accuracy as well. Better solution is usually with more calculation. The exact algorithm for KP may be explored on the basis of the branch and bound algorithm here. Intensive research will be carried out in the future.

4. Computational Experiments

By Algorithm 2, we get the approximate solutions to KP listed in Table 5. The results are listed in Table 6. The optimal value listed in Table 6 is carried out by combo [24].

Table 5.

0/1 Knapsack problems.

| No. | (wi, pi) (i = 1, 2,…, 10000) | C |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.6e + 07 | |

| 2 | (i, ln i+1) | 2.7e + 07 |

| 3 | (i, tan (πi/30000)) | 2.8e + 07 |

| 4 | (i, 100+10−4i2) | 2.9e + 07 |

| 5 | (i, 0.01i − 5600)2+1) | 3.0e + 07 |

| 6 | (i, i+tan (πi/30000)) | 3.1e + 07 |

| 7 | (i, tan (πi/30000)+0.001i2) | 3.2e + 07 |

| 8 | (i, 5000+10−6i3) | 3.3e + 07 |

| 9 | (i, tan (πi/30000)+10−6i3) | 3.4e + 07 |

| 10 | (i, arctan (0.01i)+1) | 3.5e + 07 |

| 11 | (i, 3 − lncos(10−4i)) | 3.6e + 07 |

| 12 | (i, arctan (10−4i2)+1) | 3.7e + 07 |

| 13 | (i, sin e10−4i+10−4i2) | 3.8e + 07 |

| 14 | (i, sin e10−4i+10−2i) | 3.9e + 07 |

| 15 | (i, (1/i)) | 4.0e + 07 |

| 16 | (i, (e10−4i+e−10−4i/sin (10−4i))) | 4.1e + 07 |

| 17 | (i, i2) | 4.2e + 07 |

| 18 | (i, i+2+εi), εi ~ [0,0.003] | 4.3e + 07 |

Table 6.

Approximate value and optimization value of 0/1 Knapsack problems.

| No. | Approximate value | Optimal value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4.082159596963170e + 05 | 4.082159596963174e + 05 |

| 2 | 6.541219347026785e + 04 | 6.541219347026781e + 04 |

| 3 | 4.102160742890480e + 03 | 4.102160742890481e + 03 |

| 4 | 2.462154058619999e + 07 | 2.462154058620000e + 07 |

| 5 | 8.338180285999998e + 08 | 8.338180286000001e + 08 |

| 6 | 3.100447382723671e + 07 | 3.100447382723672e + 07 |

| 7 | 2.613912845586523e + 07 | 2.613912845586526e + 07 |

| 8 | 2.232528710024500e + 09 | 2.232528710024500e + 09 |

| 9 | 2.244286940564110e + 09 | 2.244286940564110e + 09 |

| 10 | 2.096538351264514e + 04 | 2.096538351264514e + 04 |

| 11 | 2.655627458756987e + 04 | 2.655627458756988e + 04 |

| 12 | 2.189122733748200e + 04 | 2.189122733748204e + 04 |

| 13 | 2.942021969836180e + 07 | 2.942021969836181e + 07 |

| 14 | 3.981146835799920e + 05 | 3.981146835799920e + 05 |

| 15 | 9.675897955855723 | 9.675897955855723 |

| 16 | 1.997554888239176e + 05 | 1.997554888239177e + 05 |

| 17 | 3.120269950000000e + 11 | 3.120269950000000e + 11 |

| 18 | 4.301855990805434e + 07 | 4.301855990837396e + 07 |

From Table 6, we find that the approximate solutions are almost the optimal solutions in 18 instances. It implicates that the approximate algorithm proposed here achieves high precision in solving KP.

In Table 7 lists the experimental results of the solutions for KP listed in Table 2 by Algorithm 2. The upper bound listed in Table 4 is carried out by equation (11) in Section 2.

Table 7.

Relative average error to the upper bound (ppm).

| R | No. 1 | No. 2 | No. 3 | No. 4 | No. 5 | No. 6 | No. 7 | No. 8 | No. 9 | No. 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 103 | 5.6579 | 2.7082 | 1.6469 | 0.4003 | 0 | 1.2883 | 0.0573 | 100.5351 | 41.0547 | 24.8855 |

| 104 | 0.3227 | 1.5208 | 0.7258 | 0.0157 | 0.0132 | 0.4878 | 0 | 46.7007 | 0.131 | 21.4483 |

| 105 | 0.0591 | 1.1447 | 0.4877 | 0.0141 | 0.0444 | 0.2357 | 0.0044 | 43.6594 | 0.0148 | 19.1698 |

| 106 | 0.0577 | 1.1524 | 0.6731 | 0.0185 | 0.0328 | 0.246 | 0.0047 | 50.0126 | 0.0014 | 19.21 |

| 107 | 0.0510 | 1.205 | 0.5800 | 0.0229 | 0.0192 | 0.1975 | 0.0034 | 49.9764 | 0.0001 | 14.8858 |

From Table 7, we see that the relative average error of 100 instances is almost less than 0.0001. The experiment result shows that the approximate algorithm proposed here can achieve high accuracy.

From Table 8, we find that the upper bound of E-kKP makes key contribution in FPTAS. Firstly, the initial solution constructed on the basis of the solution to the upper bound of E-kKP is similar with the optimal solution. For example, there are only 4 elements different between the initial solution and the optimal solution to E-kKP where k equals to 19, while there are 8 elements different between the initial solution constructed by efficiency and the optimal solution to KP in Table 8. Secondly, the differences between the initial solution and the solution to the upper bound of E-kKP are near to the item dkk. It is to say, we search the optimal solution to KP in a core with small size on the basis of the solution to the upper bound of E-kKP. While the optimal solution to KP in a core with large size on the basis of the solution to the upper bound of Dantzig. So, algorithms proposed here is easy to get approximate solution to KP.

Table 8.

Relation between (pi-1.0003121wi) and the optimal solution (xiopt) in Example 1.

| i | w i | p i | (pi/wi) | e j | p i − 1.0003121wi | d 19l | x i opt | x i ei | z i (19) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 4.877 | 5.8853 | 1.20674595 | 2 | 1.006714385 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1.7856 | 2.7924 | 1.563844086 | 1 | 1.006219464 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 4 | 7.0943 | 8.0992 | 1.141648929 | 4 | 1.002593494 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7 | 13.9249 | 14.9319 | 1.072316498 | 7 | 1.002472723 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 7.8807 | 8.885 | 1.127437918 | 5 | 1.001737819 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | 6.3493 | 7.3521 | 1.15793867 | 3 | 1.000735709 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 10 | 24.2688 | 25.2767 | 1.04153069 | 10 | 1.000009703 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 8.5593 | 9.5616 | 1.117100697 | 6 | 0.999517192 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 9 | 21.0881 | 22.0925 | 1.047628757 | 9 | 0.997543816 | 9 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 16 | 37.1566 | 38.1662 | 1.027171485 | 16 | 0.997519609 | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8 | 19.6114 | 20.6148 | 1.051164119 | 8 | 0.997023922 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13 | 32.7739 | 33.7797 | 1.030689054 | 13 | 0.995144517 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 18 | 39.6104 | 40.6175 | 1.025425141 | 18 | 0.994221827 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 11 | 27.3441 | 28.3472 | 1.03668433 | 11 | 0.994209859 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 27 | 47.8753 | 48.8848 | 1.02108603 | 26 | 0.993934735 | 15 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 20 | 40.7362 | 41.7432 | 1.024720028 | 20 | 0.993755806 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 21 | 42.4565 | 43.463 | 1.023706617 | 21 | 0.9926965 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 17 | 37.887 | 38.892 | 1.026526249 | 17 | 0.992682141 | 18 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 26 | 47.8583 | 48.866 | 1.021055909 | 27 | 0.992140262 | 19 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 14 | 32.787 | 33.7898 | 1.030585293 | 14 | 0.992140258 | 20 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 28 | 47.9746 | 48.9822 | 1.021002781 | 28 | 0.99200245 | 21 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 24 | 45.7868 | 46.7932 | 1.021980134 | 23 | 0.99151375 | 22 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | 31.618 | 32.6189 | 1.031656019 | 12 | 0.990620324 | 23 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 15 | 33.9368 | 34.9379 | 1.029498951 | 15 | 0.990066434 | 24 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 19 | 40.014 | 41.0159 | 1.025038736 | 19 | 0.988890608 | 25 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 30 | 48.5296 | 49.5335 | 1.020686344 | 30 | 0.988122008 | 26 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 25 | 46.6997 | 47.7013 | 1.021447675 | 25 | 0.986416947 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 23 | 45.6688 | 46.6693 | 1.021907736 | 24 | 0.985652114 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 22 | 45.2896 | 46.2899 | 1.022086748 | 22 | 0.9855754 | 29 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 29 | 48.2444 | 49.2448 | 1.020736085 | 29 | 0.984714732 | 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

∗ p d 19l − 1.0003121wd19l ≥ pd19l+1 − 1.0003121wd19l+1, (pej/wej) ≥ (pej+1/wej+1), j, l=1,2, ⋯, 29. (xiei) is an initial solution constructed in descending order of efficiency.

Furthermore, no better solution of E-kKP exists when the objective value fa of the approximate solution achieved before is larger than the upper bound Bk. So we only search solution of E-kKP with upper bound larger than fa which is in the neighborhood of the optimal solution to the upper bound of E-kKP. The candidate strategy makes the search in polynomial time and the solution with high accuracy in Algorithm 1. The upper bound of E-kKP plays important role in decreasing calculation of the approximate solution of E-kKP in Algorithm 2 as well.

5. Conclusion

It is still difficult to obtain the exact solution for large scale 0-1 knapsack problem directly. Here a fast polynomial approximate solution is proposed on the basis of the upper bound for KP. The exact solution to KP is in the neighborhood of the solution to the upper bound for E-kKP. Therefore, it is possible to find an approximation with high accuracy in the neighborhood of the solution to the upper bound for E-kKP where k is near to the critical item s. All in all, as the basis of fast exact algorithm for KP, it is important to obtain an approximate solution and the upper bound for KP. In order to obtain a fast exact solution to KP, more intensive research on variables reduction need be conducted in the future.

Data Availability

All data inside the manuscript have been specified clearly in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known conflicts financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Sahni S. Approximate algorithms for the 0/1 knapsack problem. Journal of the ACM . 1975;22(1):115–124. doi: 10.1145/321864.321873. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibarra O. H., Kim C. Fast approximation algorithms for the knapsack and sum of Subset problems. Journal of the ACM . 1975;22(4):463–468. doi: 10.1145/321906.321909. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caprara A., Kellerer H., Pferschy U., Pisinger D. Approximation algorithms for knapsack problems with cardinality constraints. European Journal of Operational Research . 2000;123(2):333–345. doi: 10.1016/s0377-2217(99)00261-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zou D., Gao L., Li S., Wu J. Solving 0–1 knapsack problem by a novel global harmony search algorithm. Applied Soft Computing . 2011;11(2):1556–1564. doi: 10.1016/j.asoc.2010.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng Y., Wang G.-Ge, Gao X.-Z. A novel hybrid cuckoo search algorithm with global harmony search for 0-1 knapsack problems. International Journal of Computational Intelligence Systems . 2016;9(6):1174–1190. doi: 10.1080/18756891.2016.1256577. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang X., Huang S., Hu Y., Zhang Y., Mahadevan S., Deng Y. Solving 0-1 knapsack problems based on amoeboid organism algorithm. Applied Mathematics and Computation . 2013;219(19):9959–9970. doi: 10.1016/j.amc.2013.04.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Feng Y., Jia Ke, He Y. An Improved Hybrid Encoding Cuckoo Search Algorithm for 0-1 Knapsack Problems. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience . 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/970456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Feng Y., Wang G.-Ge, Deb S., Lu M., Zhao X.-J. Solving 0-1 Knapsack Problem by a Novel Binary Monarch Butterflfly Optimization. Neural Computing & Applications . 2015;28 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Razavi S. F., Sajedi H. Cognitive discrete gravitational search algorithm for solving 0-1 knapsack problem. Journal of Intelligent and Fuzzy Systems . 2015;29(5):2247–2258. doi: 10.3233/IFS-151700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhou Y., Li L., Ma M. A Complex-Valued Encoding Bat Algorithm for Solving 0–1 Knapsack Problem. Neural Processing Letters . 2015;44 doi: 10.1007/s11063-015-9465-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y., Bao Z., Luo Q., Zhang S. A Complex-Valued Encoding Wind Driven Optimization for the 0-1 Knapsack Problem. Applied Intelligence . 2016;46 doi: 10.1007/s10489-016-0855-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu W.-L., Gong Y.-J., Chen W.-N., Liu Z., Wang H., Zhang J. Coordinated charging scheduling of electric vehicles: a mixed-variable differential evolution approach. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems . 2020;21(12):5094–5109. doi: 10.1109/tits.2019.2948596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou S., Xing L., Zheng X., Du N., Wang L., Zhang Q. A self-adaptive differential evolution algorithm for scheduling a single batch-processing machine with arbitrary job sizes and release times. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics . 2021;51(3):1430–1442. doi: 10.1109/tcyb.2019.2939219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao F., He X., Wang L. A two-stage cooperative evolutionary algorithm with problem-specific knowledge for energy-efficient scheduling of No-wait flow-shop problem. IEEE Transactions on Cybernetics . 2021;51(11):5291–5303. doi: 10.1109/tcyb.2020.3025662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao F., Zhang L., Cao J., Tang J. A cooperative water wave optimization algorithm with reinforcement learning for the distributed assembly no-idle flowshop scheduling problem. Computers & Industrial Engineering . 2021;153(10) doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2020.107082.107082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao F., Di S., Cao J., Tang J. A novel cooperative multi-stage hyper-heuristic for combination optimization problems. Complex System Modeling and Simulation . 2021;1(2):91–108. doi: 10.23919/csms.2021.0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pisiginger D. An Expanding Core Algorithm for the Exact 0-1 Knapsack Problem. European Journal of Operational Research . 1995;87 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisiginger D. Core problems in knapsack algorithms . 1999 doi: 10.1287/opre.47.4.570. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z., Gao Li, Wang H. A hybrid one dimensional optimization. Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Electronics, Communications and Networks (CECNET IV); December 2014; Beijing, China. pp. 409–414. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pisinger D. Where are the hard knapsack problems? Computers & Operations Research . 2005;32(9):2271–2284. doi: 10.1016/j.cor.2004.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martello S., Toth P. An upper bound for the zero-one knapsack problem and a branch and bound algorithm. European Journal of Operational Research . 1977;1(3):169–175. doi: 10.1016/0377-2217(77)90024-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martello S., Toth P. A new algorithm for the 0-1 knapsack problem. Management Science . 1988;34(5):633–644. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.34.5.633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martello S., Toth P. Upper bounds and algorithms for hard 0-1 knapsack problems. Operations Research . 1997;45(5):768–778. doi: 10.1287/opre.45.5.768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martello S., Pisinger D., Toth P. Dynamic programming and strong bounds for the 0-1 knapsack problem. Management Science . 1999;45(3):414–424. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.45.3.414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data inside the manuscript have been specified clearly in the manuscript.